4

Compelling insights

IBM is listening again

‘How could such truly talented people allow themselves to get into such a morass?’ So asked Lou Gerstner in response to what he found when he joined IBM as chairman and CEO in 1993, with the brief of turning around the faltering company.1 The story of Gerstner’s revival of IBM has become hackneyed through admiring repetition, but that admiration is more than justified. Pertinently for us, the story neatly illustrates the importance of the first stage of momentum design.

Almost immediately on arrival he realized that IBM, which had always been famously customer-centred, was no longer focusing on the external world. It was obsessed by internal processes and systems. Senior executives talked mostly to each other and made decisions based on lengthy reports and detailed analysis. Their over-reliance on assistants distanced them from the heart of their business – their customers. It was the old problem of big-company inertia.

One story in particular encapsulates the phenomenon. Gerstner was meeting a senior executive responsible for a crucial part of the business. When he arrived at the man’s office, he was perplexed to see a dozen people awaiting him. Gerstner was told that staff frequently attended CEO briefings to ensure that ‘there’s always someone who knows the answer’.

Gerstner knew that to regain IBM’s lost momentum, he had to get the company away from its own internal systems and refocused on the external world. In other words, it needed less analysis and more exploration. He asked his staff to organize meetings with customers all over the world, and he set out on an extensive travel schedule that packed his days with customer meetings.

Like a humble beginner, he started asking questions exploring where IBM had gone wrong and seeking insights into how it could better serve its customers. Six months later, the message came back from the media: ‘IBM is listening again.’ Just four words, but they summarized the 80-year story of the company – IBM used to listen to customers, IBM stopped listening, IBM is listening again. These four words were worth billions of dollars in market capitalization.

Despite pressure from financial markets, Gerstner said he would not rush into formulating new strategies until he had gone around the company and its customers. So, although not much had tangibly changed at IBM in those six months, the outside world viewed the company more positively. External stakeholders gave the new CEO their trust because he had demonstrated that customers were to be at the centre of everything that IBM did. Customer focus would replace internal focus.

Why did the market put so much importance on this? Because observers knew where the new orientation would lead. Gerstner was embarking on a voyage of discovery exploring unsatisfied customers’ needs. In terms of our framework, this phase is the first stage in the systematic implementation of a momentum strategy. Its importance lies in its results – the compelling insights that fuel momentum.

The value-origination blind spot

For many years before this, IBM had been a momentum-powered firm. By focusing on customers and their needs, it had been able to uncover the compelling insights essential to the value origination process that lies at the base of a successful momentum strategy. By the 1970s, the company had a 70 per cent share of the global market in mainframe computers. It was the CEOs’ favourite supplier, with a price premium over its competitors that reflected its products’ perceived superior value – the vibrancy of its offer. Then IBM strayed off course as it became more and more internally focused – it simply stopped seeing the things it used to see, because it wasn’t looking anymore. Like many successful companies, IBM had become complacent. It no longer enjoyed the power of the momentum effect.

In IBM’s case, it missed every single fast-growing development in its industry during the 1980s and early ’90s – minicomputers, microcomputers, application software and services. These were not minor mistakes, they were huge mistakes worth several tens of billions of dollars each. They progressively undermined IBM’s potential for profitable growth and, eventually, they impacted the bottom line – in 1993, the company registered a record loss of $8 billion.

The answer to Gerstner’s memorable question, ‘How could such truly talented people allow themselves to get into such a morass?’ was quite simple – IBM’s momentum had stalled when it shifted its focus away from its customers.

IBM in the early ’90s was convinced that it knew its customers. That’s the problem, right there. A successful firm gets set in its ways of serving its customers and develops strong views about what they need. It believes it is customer-oriented, but it has a tunnel vision of its customers based on past experience. But experience is no substitute for constantly seeking new discoveries. It is useful, but momentum-powered firms also employ a systematic process of exploration – they are thirsty for new and compelling insights into customers’ needs. This is why these firms see opportunities for originating new value, while momentum-deficient firms do not. Their origination blind spot is a brake slammed down, stopping momentum in its tracks.

Virgin Atlantic

This kind of blind spot in large companies is well illustrated by the story of one of the greatest discoverers of compelling insights, Richard Branson. He gave the name ‘Virgin’ to his companies and products to signal that he knew nothing about the businesses in which he got involved. The message to the established competition was clear: ‘I know nothing, and this will be my strength. I will develop novel solutions. You believe your experience is a strong asset, but it is really your biggest liability – you are stuck in tradition.’ He proceeded to innovate in a variety of markets, including music, retailing and airlines. In none of these sectors did Virgin’s innovations stem from technology – they were all driven by superior customer understanding.

Of all the Virgin companies, the airline Virgin Atlantic shines out as one of the most complete examples of a momentum-powered firm. Because of its focus on customers, Virgin Atlantic has always stood out from the crowd by doing things differently. It created a new name – Upper Class – for a service with first class standards at business class prices. It was the first airline to offer a limousine service, a check-in service in the parking area and an unconventional passenger lounge. It was the first airline to offer all passengers a video entertainment system.

But one of the finest examples of its customer orientation was the tailoring service it offered for a time on its London to Hong Kong flight. A tailor in Virgin’s business lounge at Heathrow would measure passengers waiting for their flight, then phone the details to another tailor in Hong Kong, who would make up the outfit while the plane was in flight. The Virgin Atlantic passenger could then pick up a brand new, pressed, tailor-made suit on arrival in Hong Kong. The company no doubt made a margin on the service, but its real value was the value it added for the customer – and the fantastic, attention getting public relations it generated, developing yet more favourable buzz for the company.

All these innovations, big and small, arise from a continuous search to bring more value to customers, and thus to Virgin Atlantic. Its staff excel at the open exploration that constantly builds understanding of its customers and provides the compelling insights that fuel momentum. Like all momentum-powered firms, Virgin Atlantic realizes that its knowledge of its customers will never be perfect and can always be improved. These firms continually explore the customer universe for the insights that create opportunities for profitable growth. These insights are the source of the traction to build momentum.

Customer insights

Let us now take a look at three additional examples that illustrate how compelling customer insights are at the heart of a momentum strategy.

3M – Post-it Notes

The yellow sticky-paper reminders known as Post-it Notes, a trademark of 3M, are a great example of how customer insight can bring enormous commercial success. In 1968, Spence Silver, a 3M researcher, tried to make a stronger adhesive tape and ended up with a semi-sticky adhesive. Not exactly a storming success given what he was trying to do, but he suspected he had something valuable – he just didn’t know what to do with it.

Six years later, Arthur Fry, another 3M scientist, stumbled onto the killer application. When singing in his church choir, he frequently dropped bookmarks from his hymn book. He needed something that would stick without being too sticky – something rather like the weak glue his colleague had created. With that, the Post-it was born.

This example highlights the importance of applying compelling customer insights to a technological innovation. 3M’s ‘unsticky’ glue was nothing more than an interesting curiosity from a scientific point of view, but it was the discovery of a compelling customer insight that enabled this innovation to create enormous value for 3M.

Alcoa Packaging – Fridge Pack

The aluminum company Alcoa has a packaging division that makes cans for soft-drink companies. Hunting for customer insights, its managers decided to visit the end users of their products rather than limiting themselves to talks with their direct customers, companies like Coca-Cola.

Insight came from observing the career of a 12-pack of cans in an ordinary fridge. When full, the pack is highly visible, an invitation to the next person who opens the door to grab a can. But as cans are taken away, those remaining are left hiding at the back. Alcoa looked for a way to make these orphan cans visible upfront. The solution was a cardboard package with the cans placed horizontally. Each time a can was taken, another rolled forward.

A Coca-Cola bottler in the south-east was the first to apply the Fridge Pack. After one year, sales of 12-packs rose 25 per cent, contributing a full point to the bottler’s 2.8 per cent total volume growth.2

Alcoa didn’t just ask its engineers to innovate. It didn’t just talk to its direct customers. It went outside and met the end user at home, examining its products with new eyes – and its solution was not even in aluminum but in cardboard, completely outside the company’s normal line of business!

Dassault – the Falcon 7X aircraft

Designing an aircraft is a long, complicated process that involves thousands and thousands of interdependent parts. Many problems are not predicted during design and have to be corrected during the first few years of production, which increases an aircraft’s cost. Traditional design was a closeted, secretive process, but Dassault realized that involving its customers and suppliers at an early stage of development could create more value for all parties.

The Falcon 7X was the first plane designed using new software that allowed engineers to simulate the impact of every possible action. Dassault decided to use this virtual platform to involve external stakeholders, and it brought users, maintenance firms and suppliers into the prototype discussions. A detailed online image of the virtual aircraft enabled these different parties to make contributions to the design before it was finalized.

Dassault reasoned that this approach had the potential to create more value for its customers, for its partners and for itself. How right they were. The different stakeholders improved many elements of the aircraft’s design, which led to much lower operating and manufacturing costs and a quicker delivery time. Assembly time was cut by more than 50 per cent compared to earlier models, and tooling costs by 66 per cent.3 But the plane wasn’t just cheaper to make – it was better. Word got around. Pre-orders swelled. The increased sales resulting from the aircraft’s improved quality were perfect vindication of the policy of customer focus.

The systematic discovery of compelling insights

These three examples demonstrate how the discovery of compelling insights builds momentum. They also show that there is no single path to exploring for new growth opportunities. What counts is for firms to realize the importance of taking a systematic approach to searching for insights, and that any genuinely compelling insights acquired must be translated into effective actions that generate momentum. As we will see in the next three chapters, this means investigating insights in terms of the compelling value and compelling equity that they reveal, then using that information to design power offers. For the moment, however, we will consider how the process of discovering compelling insights can be made more rigorous and reliable.

In most companies, what activity there is in this area is usually marked out by the opposite of rigour and reliability. If insights arrive, they are the result of haphazard and happy chance. And yet if a true and systematic process of discovery aimed at uncovering compelling insights is installed, it can unearth a vast range of opportunities. We have organized workshops in which the depth of learning, the specific insights revealed and the new attitudes created have surprised even the most sceptical participants. Most organizations are wells of knowledge, brainpower and goodwill – the challenge is to mobilize all of this in order to discover compelling insights.

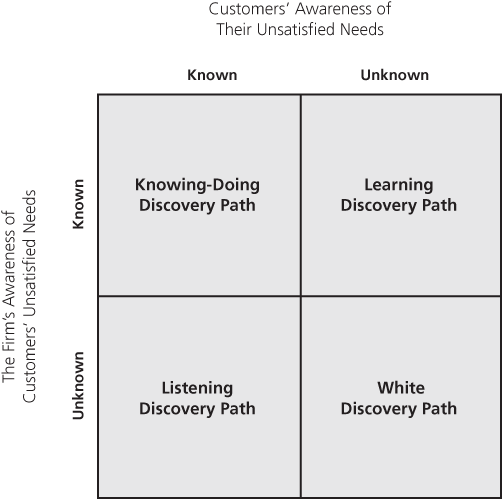

Firms need tools to help them to structure their exploration, instruments that set out and explain the different paths to discovery and suggest ways to uncover compelling insights. The insight discovery matrix, shown in Figure 4.1, is such a tool. It shows how four discovery paths are defined by the relative awareness of the two key partners – the firm and the customers.4

Figure 4.1 The insight discovery matrix

This matrix is divided into four separate discovery paths – each conceals unlimited opportunities for growth. Before describing them in more detail, let’s illustrate them with software applications for personal computing.

- The knowing–doing discovery path contains unsatisfied customer needs that both the firm and customers are aware of. In the case of PCs, this would be repeated demands from users for greater simplicity, reliability and support that are well-known to firms but which many do not resolve satisfactorily.

- The listening discovery path contains unsatisfied needs that some customers are aware of but the firm is not. For example, many applications have been, and could be further, improved following users’ feedback and suggestions that developers could not have imagined on their own.

- The learning discovery path contains unsatisfied customer needs that the firm has unveiled of which the customer is unaware. In this quadrant, we have all those applications that users are failing to use fully because – due to the inadequate learning approaches that the firms offer – they are unaware of their potential.

- The white discovery path contains unsatisfied needs that no one has yet discovered but which may represent tremendous future business opportunities. This unexplored white space represents the ultimate frontier, and it includes nearly all the most powerful applications we take for granted today. At one point, neither their potential users nor their future creators imagined the enormous potential of spreadsheets, Internet browsers or online telephony.

We will shortly follow the exploration process and travel along these four discovery paths but let’s first illustrate them with an example to which we can all relate – retail banking, an industry generally guilty of a strong internal focus that frequently irritates its customers. The matrix for this industry is set out in Figure 4.2.

Figure 4.2 The insight discovery matrix of retail banking

Bucking that trend over the past decade or so have been the efforts of new and progressive financial services companies including branchless banks5 or innovative bricks-and-mortar institutions such as Commerce Bank. Calling itself ‘America’s most convenient bank’, Commerce Bank grew from a single branch opened in New Jersey in 1973 to having nearly 470 branches, concentrated in the New York/New Jersey area, and 2.4 million customers in 2007, principally by offering better and more convenient service than traditional banks.6

The knowing–doing discovery path

This quadrant concerns opportunities that are known to both a firm and its customers. There are two principal, and quite different, reasons that explain why these unsatisfied needs are not exploited – unavailable technology and corporate apathy.

The first of these is excusable. At any point in time, many unsatisfied needs must wait for further scientific developments that can then be translated into business opportunities. The second is not excusable. Corporate apathy is the area to explore in the knowing–doing path, the morass that Lou Gerstner spotted at IBM. It is the swampland of the momentum-deficient league. It is also where the ‘low-hanging fruit’ – the quick wins – are located. The problem here is not to discover the opportunities: they are already well known. Neither is the problem to develop technologies. This is not the issue. It is to discover the reasons why these opportunities have not yet been exploited, and then to find the ways to achieve change.7

In retail banking, apathy rather than technology has been the main barrier in the knowing–doing path. For decades, everyone knew that inconvenient opening hours, poor service quality and high charges created customer dissatisfaction. Despite this, nothing was done until institutions such as Commerce Bank built enormous momentum by turning these givens on their head. Commerce Bank offered seven day a week opening, extended opening hours, free cheque accounts and friendly staff. They offered free coin counting machines in their branches that anyone could use to turn loose change into notes. They made it easier for busy people to bank. In doing so they became the bank with the highest satisfaction rating in the New York area and generated exceptional levels of deposits.8

The listening discovery path

The listening path describes unsatisfied needs that are known to some customers but not to the firm. Many entrepreneurs enter the world of business as frustrated customers with unsatisfied needs who develop solutions aimed at others like themselves. Most often, these needs are perceived and expressed by only a small number of leading customers. The challenge for large firms is to detect the weak signals that this minority sends out through the static of the marketplace.

In retail banking, customer-oriented institutions such as Commerce Bank came to realize that customers felt frustrated with traditional banks – that they were treated with a lack of respect, that their time was undervalued and wasted and that the banking experience was a source of anxiety. One indicator of Commerce Bank’s excellence at listening is the fact that it resolves customer complaints two days faster than the average time taken by its competitors.9

The learning discovery path

Many new products fall into this category at the beginning of their life cycle – a firm knows that its customers have unsatisfied needs before they do. This was seen with past innovations such as automobiles, computers and mobile phones. This cycle is ongoing, and the prospects for customer learning are unlimited.

These growth opportunities lie in a firm’s ability to educate and persuade customers about the value of a new offering. Consider a story recounted in Malcolm Gladwell’s Blink: the Aeron office chair.10 This chair is now regarded as a design classic – there’s one in the permanent collection of New York’s Museum of Modern Art. And yet, as Gladwell points out, when it was introduced in 1993 it was so unusual that focus groups regularly scored its aesthetics as low as 2 and never higher than 6 on a 1-to-10 scale. By the late 1990s, annual sales were growing by 50 to 70 per cent despite a hefty price premium. Today, focus groups score its aesthetics an average of 8 out of 10. Customers had to be educated as to the ergonomic brilliance behind its unusual looks.

Returning to the retail banking sector, the learning path obviously includes the development of new products. Some of these financial products require more customer learning than others. It’s easy to explain a simple product such as a mobile alert service that sends a text message to a customer’s mobile phone when their account balance goes into the red. But how about the ‘offset mortgage’ that some innovative banks11 in the UK offer customers? These offset all of the customer’s deposits with the bank – e.g. the balances in cheque and savings accounts – against an outstanding mortgage when calculating the monthly interest due on that mortgage. Interest is charged only on the net ‘balance’, reducing the interest due on the mortgage without the need for any action by the customer. The full capital must be paid off within the term, obviously, but customers can save thousands in interest charges over the life of the mortgage and consequently repay the loan sooner. Customers fully appreciate this novel product – after they understand how it works.

The white discovery path

This quadrant represents the real unknown for both customers and firms. We call it white because its opportunities are like virgin land covered with snow. It represents the future innovations that neither party can anticipate. The matrix is fluid – as new technologies progress and customer needs evolve, these hidden growth opportunities will be unveiled and move to one of the other three discovery paths.

In the retail banking sector, this quadrant included growth opportunities from new technology that led to telebanking, Internet banking and mobile-phone banking. It also included unexpected customer discoveries such as highly personalized banking through the use of CRM systems and the creation of ‘banking stores’, as pioneered by Commerce Bank. The significant discovery was this – customers had negative feelings about traditional bank ‘branches’, while they were positively inclined toward visiting stores. Commerce Bank took McDonald’s as a benchmark, designing its banking stores with large bay windows and adding a drive-in. It created a welcoming experience superior to any traditional bank branch.

The exploration process

The above examples show that discovering customer insights to drive momentum requires a kind of process different from the methods that large corporations traditionally use. While analytical processes are one of the foundations of proper management, they can destroy opportunities to discover new and compelling insights.

The danger of an overly analytical approach is that it leads firms to improve what they’re doing already, rather than investigating other sometimes radically different avenues. Remember the value origination blind spot? Genuinely compelling insights will be uncovered not through analysis but through exploration.

Guiding exploration

Creativity is the only limit here. Usable tools include focus groups, think tanks, projective techniques, inspirational visits and field trips, as well as video observation and other ethnographic methods. But they all have one thing in common – they encourage employees to meet customers, involve customers and think in terms of customers. That is the only way to uncover the compelling insights that get momentum started.

The knowing–doing discovery gap is where we find the low-hanging fruit. These unmet customer needs could be satisfied easily but are being restrained by internal psychological, cultural or organizational barriers. These barriers could include the defence of territories within the company, the spectre of cannibalization or the fear of failure. The exploration process for this path should involve an investigation of the low-hanging fruit and of the reasons why the firm is not exploiting them. In our experience, this is easily achieved through workshops led by a trusted external moderator. Such a workshop should conclude by identifying the top opportunities and building a commitment toward their positive exploitation. Systematic investigation and mobilization of management are essential to seize these low-hanging fruit.

The first cause of the listening gap is that in many organizations managers remain distant from their customers, either consciously or subconsciously. Bank managers rarely do their own banking by standing in line, airline executives never fly economy, automobile managers are chauffeur driven in company cars, consumer-goods managers buy supplies discounted at their headquarters’ store. These managers rarely experience their products or services in the same conditions as customers, and almost never at full price. For the same reasons they seldom meet customers at all, or not for enough time to actually share their real concerns.

The most effective – and easiest – way to explore the listening discovery path is to spend quality time with customers. We have organized fruitful encounters between managers and customers that lasted 15 minutes, an hour, a full day and even workshops of several days’ duration. What is important is to have sufficient time to go beyond the usual business rituals and the superficialities of social encounters, and build mutual trust and understanding.

As we will see later in the book, the concept can be taken further by having employees actually working on the customer’s premises. This is what Procter & Gamble did when it sent a couple of hundred employees to work in Wal-Mart’s Bentonville headquarters. In a similar fashion, Dell placed 30 maintenance engineers inside Boeing’s commercial aircraft facility in Seattle. In cases like these, both parties win. The customer gains superior service, and the firm creates the conditions whereby its staff can discover untapped needs.

It is also useful to engage in qualitative customer research. This is likewise based on the principle of spending quality time with customers but involves specific techniques and professional staff. The purpose is to get information from customers that they would not share in simple surveys or casual conversations. One tool often used for this purpose is focus groups, which bring together selected customers to discuss a specific issue under a moderator’s direction, while other professionals observe their behaviour and discussion behind one way mirrors. Like the anti-inflammatory gel applicator for the elderly woman’s back, valuable ideas and insights frequently emerge from such approaches.

Bridging the learning discovery gap is very much like going to a foreign country – one has to measure the difference in culture and language and adapt accordingly. When a new product is ready for launch, the business teams involved are familiar with and enthusiastic about the innovation. At this point, it’s easy to underestimate the gap between the internal momentum and the external inertia of the customer’s perspective. Many new products have missed opportunities because of this misunderstanding.

In such a situation, the customer’s state of mind should be explored thoroughly so that all potential gaps can be sealed. It is essential to understand all the blocks that could prevent customers from understanding that they have a need. This is particularly so in many medical situations where most patients do not realize the dramatic potential consequences of conditions such as obesity, hypertension or diabetes. Unless diabetic patients understand that the complications of their condition can lead to amputations, blindness and heart attacks, they do not realize how important it is to be treated. The key is to find the right approach that makes customers realize that a need that they haven’t yet fully perceived requires attention.

Often, development of a new approach to language – neologisms or euphemisms – is needed to bridge the gap between customers and company in understanding needs. For example, during the launch of Viagra, Pfizer’s appreciation of the stigma attached to the word ‘impotence’ was critical. This led to the expression ‘erectile dysfunction’ and the even more palatable acronym ED. This language enables patients to communicate more readily with their partners and doctors to discuss remedies.

The insight discovery matrix should sharpen a firm’s understanding of its customers and help in finding new growth opportunities. Within this frame, it is the virgin, unexplored white space of the unknown–unknown box that represents the ultimate frontier. Navigation there is tricky, but certain different approaches can prove helpful. The challenge is to be ahead of both customers and competitors and to lead future trends.

We have taken executives from Europe to Silicon Valley or Wal-Mart stores in the US, executives from North America to fashion hot spots in Paris and western executives to the mushrooming cities of Bangalore and Shanghai. In all these instances, the culture shock resulting from witnessing different customer groups and different customer solutions led to new insights.

Another approach is to extrapolate customer and technological trends to the limit in order to detect possible growth opportunities with a plausible commercial future. Confronting consumer trends with technological trends should lead to potential growth opportunities. For example, in the IT and communications market, a think tank could investigate what needs might exist and be satisfied if the cost of chips and telecommunications became zero. Considering this hypothesis in the light of the growing percentage of the population above retirement age could identify a large number of growth opportunities that could then be prioritized and further analysed for their technological and economic feasibility.

In-depth consumer research is also a valuable tool in this unknown–unknown quadrant. The issue is to identify needs that customers have but cannot yet express or articulate. General projective techniques are well-known tools for this area. Ethnographic research is a promising trend that observes customers in their own natural environment. For consumer goods, this means in their normal lives at home, while shopping, etc. Alcoa used this approach in the discovery of the insights behind the Fridge Pack. In the case of business customers, these observations would be in workplaces, offices, plants or construction sites. More sophisticated methodologies are constantly being developed in this field.12

To bridge the white discovery gap, the challenge is to identify opportunities that neither the customers nor the firms have detected. It is not easy – it takes time to develop empathy with deep customer trends. The leader who best exemplifies the ability to tap into such pure discoveries is Steve Jobs. He first played a central role in the personal computer revolution through his leadership of Apple. This led to the creation of the Apple I and II and the Apple Macintosh, which incorporated the graphic user interface and ball mouse device originally developed by Xerox. Later, Jobs led the development of more successful products such as the iMac, the iPod, iTunes and, separately, Pixar, which produced six of history’s most successful animated films.

Enabling exploration

Exploratory processes, essential for discovering customer opportunities, are simple to implement. Indeed, most entrepreneurs function with an exploratory mindset without any training or coaching. Employees welcome customer exploration – it can help to mobilize a workforce.

So why don’t large firms use these exploratory tools more often? The problem is that they conflict with the dominant analytical approach that traditional management favours. In our experience, the three most important areas of conflict between analytical and exploratory approaches to customers are concern about taking time out, resistance to external activities and mistrust of small sample sizes.

Traditional management emphasizes the efficient and effective use of time for productive activities. ‘Good’ management behaviour equates efficiency with busyness. In contrast, an exploratory approach to customers leads to investing time in tasks that may be unproductive in the short term, with the added perceived risk that they will lead to no concrete results at all. The odd thing is that in a crisis situation, such as Lou Gerstner encountered when he joined IBM, leaders often do take time out to reconsider the fundamentals. Why wait for a crisis when you could prevent one from happening?

Naturally, common sense should apply. As with R&D, customer exploration should not become a licence for managers to gleefully run away from business pressures. Exploratory tools should be carefully managed to increase the likelihood of significant returns – but they must not be neglected. Our experience has shown that neglect of the discovery process by most firms almost inevitably guarantees positive results for those who have adopted a more exploratory approach. Creating time out is the first prerequisite to enable exploration.

Going out of the company premises and engaging oneself in external activities is the second crucial condition for exploration of insights. Traditional management largely takes place in the comfortable, familiar territory of office buildings and hierarchically supervised company sites. Managers might leave their secure offices on business trips, but they mostly visit familiar locations such as other offices, existing suppliers or partners. Even salespeople rarely dip their toes into the waters of ‘missionary’ selling by visiting non-customers.

The usual working environment is a comfort zone, and leaving to investigate customers, ex-customers and non-customers is essential for exploring opportunities. This is particularly pertinent for employees who seldom have the chance to meet customers – marketers, engineers, scientists, finance and HR staff. Go where Gerstner went – go and visit customers!

The third enabler of exploration is recognizing that the in-depth discovery of a few non-representative customers is essential for unveiling compelling insights. This is, however, going against some of the sacred cows of professional management. For example, one essential guideline for market research is the importance of using representative customer samples, in terms of both quality and quantity. But exploration often works best when it first involves in-depth investigation of a single customer who is ahead of the crowd, and therefore not representative at all of the mass. Remember Arthur Fry and the Post-it Note? Sample size: one.

Entrepreneurs are frequently inspired by the vision of one customer with an unsatisfied need – sometimes the frustrated entrepreneur him or herself, or a close acquaintance. Edwin H. Land was motivated to work on the concept of instantaneous photography not by scientific curiosity but by the naive gesture of his little daughter. After he snapped her picture while on holiday, she tried to open the camera to see the pictures inside. He had to explain the lengthy waiting process behind developing and printing film. His daughter’s disappointment inspired Land to invent the Polaroid camera.

Investigating individual customers can be just as fruitful as ‘representative’ samples. This deep individual exploration can then be validated by larger-scale studies. It is at this point that the analytical approach comes into play – but not until the full potential that these open, exploratory processes can reveal is uncovered.

The paradigm of the past was about who was big and who was small. Today’s winners and losers are different. Now the distinction is between those who know their customers and those who don’t, because this is how value is created. Momentum begins with the discovery of compelling customer insights, and such discoveries are only possible when firms are truly open to exploring their customers’ world.

Explore the world for insights

Firms that build momentum do it by constantly exploring – by going out and bringing what they discover back to the office. They are so focused on their customers that they feel they must understand everything about them. The reason they embark on this constant, ambitious and systematic voyage of exploration is that they are seeking new compelling insights into unsatisfied customer needs. Momentum-powered firms follow a never-ending quest to uncover the compelling insights that will shed light on new and untapped sources of compelling customer value and compelling customer equity.

A common weakness of momentum-deficient firms is the blind spot, the belief – probably not expressed and possibly not even conscious – that their products are pretty much the best they could be. Oh, maybe they could do with some tweaking, but, generally speaking, customers pretty much have everything they need. ‘We know our market’ is a frequently heard claim. That lasts until someone who really does know their customers comes along with an offer that shows just how much there was left to discover, how much more value could be originated.

The secret is exploration. Most managers would be embarrassed if they were asked how much time they spend engaging with customers, compared with time reading spreadsheets. The following guiding principles should help rectify the balance.

- Compelling insights are the launch pad of momentum. They are the first stage of the momentum design process that eventually ends in power offers and the momentum they generate. Everything that follows depends on the quality of those insights.

- Compelling customer insights help to create momentum for the firm in two ways – first, by revealing new and better ways of satisfying customer needs that lead to compelling customer value, and second by uncovering new customers and new opportunities with existing customers that will lead to compelling customer equity.

- The intense and revealing insights that drive momentum cannot be discovered through traditional management analysis alone. Managers must get out of the office and engage in genuine open exploration. Exploration is the biggest deficit in the management of large, established firms. It is essential for them to actively seek new growth directions if they wish to generate the momentum effect. Momentum-powered firms have a deep understanding of their customers because they are externally focused rather than internally obsessed. They bring the outside in.

- The insight discovery matrix offers established firms a systematic way of achieving what entrepreneurial firms manage by instinct. It sets out four discovery paths to guide their explorations – knowing–doing, listening, learning and white. The source of the greatest potential tends to lie in the virgin territory found along the white path – the needs that are currently unknown to both the firm and its customers.

- Because the exploration process takes managers outside their comfort zones, firms must do all they can to encourage and enable their employees to make the step. The activities required to discover compelling insights conflict with the analytical approach that most managers feel comfortable with. Managers must realize the potential benefits of taking time out from day-to-day activities to encounter the customer’s world. They must overcome their resistance to external activities and mistrust of small sample sizes.

Compelling insights offer the thrill of the ‘aha’ moment. To paraphrase Isaac Asimov, the most exciting moment in discovery is not when someone shouts ‘Eureka’ but when they mutter ‘Now, that’s funny’. The dawning realization that you might be on to something marks the point when your compelling insights must be explored, fleshed out and refined. These insights can fuel a momentum strategy only if they have the potential to make customer value or customer equity more compelling. The next chapter will guide us in investigating the first of these two avenues.