6

THE PRODUCTION PLAN

Production Plan Overview

Now that you are ready to make the leap into production, it is time to put a plan in place. This complex undertaking is a highly collaborative effort which involves the core creative and technical team. Ultimately, the production plan should function as a road-map that ensures everyone is fully invested and walking on the same path. Devising a production plan is a methodical yet creative process. In this step, the producer has to commit his or her vision to paper. If this vision is deficient, as in any creative process, the producer must be flexible and open to questioning and changing his or her parameters in order to come up with alternative scenarios. Devising the plan entails consulting with the core team and department heads, drawing on their expertise in order to develop an educated approach to the project. Each production step will require a certain number of presuppositions. The end goal is to create a plan made up of four key items including the budget, schedule, crew plan, and list of assumptions. Because every phase in animation is interdependent, the producer must be able to anticipate all possibilities and adjust the production plan in order to accommodate each component.

A producer's main task is to ask lots of questions in order to gather as much information as possible from the many individuals involved in bringing a project to life, such as the buyer, the director, the visual effects supervisor (if applicable), and other key parties. Once this information is assembled, the producer must figure out the best way of allocating money throughout the budget based on its creative needs. For example, if a project is strictly story-driven with simple character designs that warrant limited animation, it would be necessary to put significant funds into the areas of writing and cast/recording rather than animation. A solid example of this kind of a project can be found in Comedy Central's South Park, on which the scripting and voice recording phase can potentially continue until mere hours before airtime. If the look of a project is key to its success, the budget must be set up so that numerous creative iterations can be explored and finessed. Whatever is determined to be the best balance of resources for the project, the producer needs to see that all areas are addressed and accounted for in the budget so that there are minimal surprises mid-production. The schedule then needs to be shaped as a realistic reflection of the options available with the assumptions written to make certain that all critical points can be accommodated. Once approved, the production plan becomes a baseline tool should there be significant changes requiring overages and therefore additional funds.

Steering the Ship While Planning a Party

Amy Jupiter, Line Producer

The production plan is truly the creative brainchild of a producer. For me, production planning and managing to that plan is my favorite part of the process. It tells us the fiscal and temporal parameters to which we are working. It's a touchstone against which we constantly check back to make sure we are going in the right direction. It is a complex network of information and interdependencies that have to be taken into account every day, all day. Producing is very exciting and takes experience and a calm temperament so as not to become overwhelmed with all the information coming at you moment by moment. A good plan provides for some flexibility so that the creative vision can evolve and production management can respond to these changes.

Running and determining the many scenarios required to launch and ultimately oversee the plan is an ever-evolving illustration of all the parts that will go into creating the project. It is analogous to being the captain of a squarerigger ship in a storm. The captain has the map to guide the crew in the general direction to be traveled in addition to the expected arrival time at the ultimate destination. Meanwhile, trying to control the ship with its many moving parts while having to integrate many real-time shifts in the water and wind and crew abilities proves challenging, even in good weather, for the most seasoned of leaders.

There are a couple of high-level tools I use to start the production planning process. I begin my planning graphically by laying out a very simple overview of the time frame and major milestones of the project. The next step is to ensure that all of the stakeholders are on the same page with regard to budget goals and the general assumptions of the project. I relate this process to party planning. Everyone has different expectations, and finding a balance between the person paying for the party and the person who is giving the party sometimes proves to be the most challenging of discussions. The person giving the party (the director and creative team) focuses only on the guest experience and making the party the most memorable it can be. The person paying for the party (the studio or financier) wants to keep costs in line. Creating a strategy that ensures each stakeholder feels like they are being heard takes finesse and an advanced degree in psychology.

Having a detailed plan approved and ready for production is truly a satisfying experience, but the reality is that this is not just a one-time experience. There will be more—right when you get comfortable, inevitably something will emerge and it will be time to start changing it again.

List of Assumptions

As the budget, schedule, and crew plan are assembled, the producer must put in writing all of the areas or the parameters upon which the production plan is based. This is known as the producer's list of assumptions. It enables everyone to have a mutual understanding of the project and its requirements. When changes are made to the plan, this agreed-upon template makes it easier for both the producer and the buyer to identify and evaluate the costs and schedule revisions. Typically, the following items need to be addressed in a list of assumptions:

- The delivery date

- The schedule

- Thinking in frames

- Quotas

- The project's format, length, and technique

- Complexity analysis

- Script breakdown

- Style/art direction and design

- Average number of characters per shot

- Production methodology

- Research and development

- The crew plan

- The level of talent

- The role of key personnel

- Creative checkpoints

- The buyer's responsibilities

- The payment schedule

- The physical production plan

- Training

- Recruiting and relocation

- Reference and research material

- Archival elements

- The contingency

This list outlines the areas to be considered when building the framework for a production plan and preparing the final budget. Each of the categories listed are explained in detail so that they can be applied to planning CG and 2D productions. Because each project is unique, there may be other elements to take into account; however, the following key items must be considered when setting up any production.

Delivery Date

In a perfect world, a budget and schedule are configured without a specific delivery date so that the plan itself is driven by the creative needs of the project, but this is rarely the case. In most cases, the delivery date for the project is the producer's starting point for creating his or her strategy. This information comes from the buyer and is typically based on air or release dates. These dates can come from a number of sources, including ancillary groups involved in distribution, merchandising or promotion, or possibly a studio's overall production plan. If the delivery date is very tight, it will drive the pacing of the project. It is also a determining factor in whether the production will be done in-house, or with a subcontracting studio, or through multiple subcontractors.

The Schedule

It is critical that the producer has a schedule for reference when budgeting a show. Using the delivery date as a starting place, the producer can begin to put a preliminary schedule together. The schedule is the number of days, weeks, months, or years needed to complete the project from script to delivery. As numbers are plugged into the budget, the schedule will probably be moved around to accommodate both the creative and fiscal needs of the production. It is also important that the producer has this information available for reference so that he or she can assess staffing requirements. If the producer is using overseas subcontracting studios, it is important to investigate and plan for national holidays and local traditions that may affect the schedule.

Thinking in Frames

On a live action production, the camera rolls as long as necessary and in as many angles as possible to capture a scene, whereas in animation every shot is thought out in advance and built frame by frame. Every aspect of the character's actions and movement and the surrounding location must be created; therefore, the project becomes divided into a specified number of scenes or shots, each of which typically have a finite number of frames based on dialogue and action. The number of images per foot or second needs to be established—that is, full animation versus limited animation. If it is full animation where every frame or every other frame is drawn or rendered the animation will be extremely smooth. A classic example for full animation can be found in Richard William's “Thief and the Cobbler.” A more contemporary example is Disney's “Tangled.” Well-known examples of limited animation include animé and television series, such as Fairly Odd Parents.

Quotas

Quotas are a system by which the artwork is broken down into specific units and their completion is paced over the production's timeline. In the case of features, for example, schedules are produced with targeted weekly quotas calculated in shots, footage, or seconds for each department and individual artist. The complexity analysis and qualitative expectations (discussed later in this chapter) ultimately drive a project's quotas. Depending on the quality of animation expected, the weekly quota will reflect the optimal amount of work that can be completed. If a project is not as demanding from a qualitative standpoint and the complexity level is minimal, typically the weekly per artist quota and volume of shots generated will be higher. Referencing the look or style of an existing television series or a feature film is a great way of coming up with the quotas per artist per week per department. Once these numbers are determined, they can be plugged into the crew plan and budget for calculation. When generating the schedule, be realistic about what can be accomplished in the time available. Allowing room for creativity and facilitating production efficiency is critical to fulfilling quotas. If you are not able to evaluate the time needed per department, ask questions from reliable sources such as the director, the visual effects supervisor (if applicable), and the department head (if available)—doing so will help ensure that the project is managed well in all areas.

For a typical television series, the producer does not have to generate this information as precisely. Because production is handed off to subcontractors who return the completed episodes and manage this step of the process themselves, it is their responsibility to define quotas for their studio.

In this chapter, you will find generic master timelines or macro-schedules that outline production timeframes for television and feature projects. Note that these samples are to be used as general guidelines and should be modified to suit the processes, techniques, and needs of the particular production pipeline and software capabilities. When a production is up and running, the master schedules should be further broken down into more detailed schedules, called micro-schedules, for each department.

The following figures are used to pace a production and to set up a system by which enough work is generated in every department to create ample inventory for the artists. By evaluating the work completed in relation to the quotas on a weekly basis, the producer can assess the status of production in relation to its delivery date and budget. (See Chapter 11, “Tracking Production,” for further information.)

The television master schedule shown in Figure 6-1 illustrates 13 episodes in pre-production, production, and post-production phases using the traditional 2D format. Figure 6-2 breaks down a single episode and lists the specific production steps involved, starting with script writing and ending with delivery. All of the episodes follow the same schedule and overlap. Figure 6-3 shows how the pre-production, production, and post-production timelines compare in the creation of a 22-minute television series based on the technique used.

Figure 6-1 Television master schedule: 13 episodes in traditional 2D format.

Figure 6-2 Traditional 2D television single episode schedule: step-by-step process breakdown.

Figure 6-3 Television average production timeline comparison.

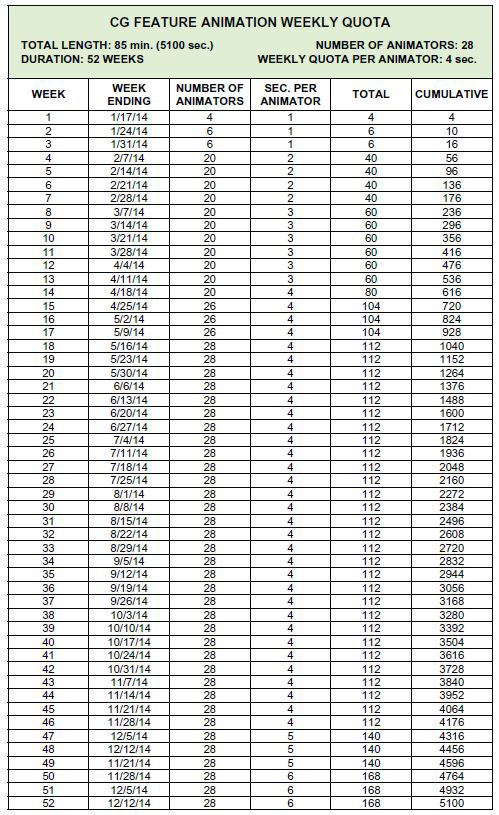

You will also find in this chapter generic schedules for a CG feature (Figure 6-4) and a traditional 2D feature (Figure 6-5). Because the processes for producing CG projects vary widely based on budget and technique, Figure 6-4 should be viewed with this in mind: the CG timeline details and feature animation quota numbers (Figure 6-6) provided here are applicable to high-end productions. The master schedule is divided into pre-production, production, and post-production. The chart illustrates the number of months each department typically runs, when they overlap, and what key stages must be completed before production can officially start. On both charts, there is an indication of a partial crew for a number of categories because in animation, many departments are interlinked. For example, on a CG feature, while “look development” tests are taking place, there is a need for staff to assist with lighting and compositing. Or, as a feature undergoes initial test screenings, notes come up that require fresh storyboarding, and it will therefore be necessary to maintain a few artists to address the script revisions. Both ramp-up time and prep time are a necessity for shot production. As departments begin work or start winding down, the crew is scaled up or down based on the numbers necessary to support completion of shots in accordance with the project's weekly quota requirements.

Managing a feature production requires two different modes of tabulation. One is the total number of shots, and the other is the actual number of frames or seconds to be animated. Table 6-1 is a reference chart converting seconds into frames and feet. Using a project that runs 85 minutes as an example, the producer would first determine the number of seconds of animation needed by converting the minutes into seconds—in this case, the total is 5,100 seconds. In order to ascertain the feature's shot production requirements, one would then apply the commonly used rule of thumb that that an average shot is roughly 3.33 seconds. By dividing the total number of seconds (5,100) by the per-shot average of 3.33 seconds, this project is set up for the completion of 1,532 shots. The next objective is to plan out how the artwork (or number of shots) can be accomplished within the parameters of the budget and schedule.

Figure 6-4 Feature production master schedule: CG format.

Figure 6-5 Feature production master schedule: traditional 2D format.

Figure 6-6 Feature production quota schedule: CG animation.

Table 6-1 Conversion Chart for Seconds, Frames, and Feet Calculations

| Seconds | Frames | Feet |

| 0.042 | 1 | 0.0625 |

| 0.083 | 2 | 0.125 |

| 0.125 | 3 | 0.187 |

| 0.167 | 4 | 0.25 |

| 0.208 | 5 | 0.312 |

| 0.250 | 6 | 0.375 |

| 0.292 | 7 | 0.437 |

| 0.333 | 8 | 0.5 |

| 0.375 | 9 | 0.56 |

| 0.417 | 10 | 0.625 |

| 0.458 | 11 | 0.687 |

| 0.500 | 12 | 0.75 |

| 0.542 | 13 | 0.812 |

| 0.583 | 14 | 0.875 |

| 0.625 | 15 | 0.937 |

| 0.667 | 16 | 1.000 |

| 0.708 | 17 | 1.0625 |

| 0.750 | 18 | 1.125 |

| 0.792 | 19 | 1.187 |

| 0.833 | 20 | 1.25 |

| 0.875 | 21 | 1.312 |

| 0.917 | 22 | 1.375 |

| 0.958 | 23 | 1.437 |

| 1.000 | 24 | 1.5 |

Using the length of 5,100 seconds and dividing that by the number of available weeks (52) determines that this project needs 28 animators to produce a total number of 4 seconds per week in order to meet the targeted quota (Figure 6-6). By contrast, as illustrated in Figure 6-7, on a 22-minute digital 2D television series, it is possible to generate 30 seconds of animation per artist per week and complete the show using 8 artists in 6 weeks.

Please note that these charts do not take into consideration sick days, vacation time, national holidays, and union holidays. All of these items must be tailored to the individual studio and country and accounted for when creating a schedule in order to set up realistic goals for the production team. Another item to consider when creating this type of a budget is ramp-up time. In the CG feature animation chart, artist quota starts with a lower scale of productivity expected, with that number gradually increasing as the artist becomes more familiar with the style and requirements of the show. Ramp-up should be part of each department's calculations. An allowance of 10 to 20 percent of additional quota should also be made for iterations based on the project's budget and qualitative expectations.

Figure 6-7 Television production quote schedule: digital 2D animation.

Project's Format, Length, and Technique

Format

Before embarking on a production plan, the producer must know the format of the project. The possible formats for an animated project include television series, TV special, short format (either for the Internet, mobile, television, or theatrical release), interstitial (small segments, shorter than a commercial, such as a promo), commercial, direct-to-DVD, and feature. Also to be determined up front is the medium (film, tape, or digital file) on which the project will be delivered and whether it will be produced in stereoscope.

Length

Early in the planning stages, the script is timed to determine the total length of the project. Television series episodes for network distribution generally run 22 minutes long each or may be comprised of two 11-minute segments; direct-to-DVD projects range from 60 to 80 minutes; and a feature can vary, usually running anywhere between 70 to 110 minutes. Animated shorts and content created for the Internet have more flexibility in terms of length. To get a ballpark running time of a script, a director may use a stopwatch while reading the pages to estimate its length. Although this method is not precise, it allows the producer to generally assess the project's running time. The rule of thumb is that one page is equivalent to one minute, but adjustments might be necessary if, for example, there is a song title inserted in the text or if an action sequence is described in just a few words.

By establishing how many minutes of animation is required, the producer can begin to set production goals. In CG and digital 2D production, shot lengths are commonly measured in seconds and frames; traditional 2D animation uses feet and frames for timing purposes.

Technique

Deciding upon the animation technique that best matches the project's content is critical because it directly affects the production process and cost. The most commonly used techniques are CG and 2D (which can include hand-drawn images and/or the use of digital assets). Stop-motion is also another option but less common. In CG and digital 2D animation, typically the conceptual materials and storyboards are drawn by hand, and all remaining production art such as asset creation—be it character, environment, prop, or visual effects—are created digitally through a myriad of stylistic and software options. Traditional paper-based 2D involves line drawings in the layout, animation, cleanup, and effects stages, which are then scanned in and integrated into the digital production pipeline. Stop-motion animation uses the process of stop-motion photography by shooting frame-by-frame 3D objects such as puppets or clay figures. An animated project may draw upon one or a combination of these techniques. The animation can be limited or full or somewhere in between, which again will be driven by the project's creative direction and/or its budget. (See Chapter 9, “Production,” for a detailed discussion on CG and 2D production processes.)

Complexity Analysis

One of the key things in budgeting is defining the complexity of a project, which is explored through a detailed analysis of the conceptual artwork and the script being used to create the production plan. A complexity analysis is a very important multi-faceted step in determining how to allocate the resources accessible on a project. The results illustrate the status that a project is in. If, for example, the material is overly ambitious and exceeds the budget and schedule allowances, then the complexity must be addressed in terms of a simplification pass to bring it into alignment with the available funds. The following sections outline the different factors that affect the complexity of a project and the types of evaluation that should be done.

Script Breakdown

The first step is to break down the script, which means generating an itemized list of every single asset that needs to be created (and when applicable) reused. This breakdown is used to drive the production plan and allocation of resources needed to create all of the various assets—character, environment, and props—for a project as well as the visual effects required. All of these elements must be subcategorized into main and secondary elements, as the main or primary assets will require more time than the secondary ones. The producer working with the director, visual effects supervisor (if applicable) and art director should analyze the number and complexity of character models locations, props, and effects. Conceptual artwork or reference material and any completed designs should also be used in tandem with this list in order to determine the amount of time or number of staff hours it will take to create the various elements from a production standpoint.

Using the script breakdown, the next step is to do a content analysis of the script: a detailed evaluation of the story that enables the producer to gain overall insight into what will be involved in producing the project. This analysis helps the producer identify sequences that may need to be prioritized and/ or require special attention. During this process, the script is once again scrutinized for a number of specific elements that can affect the size of the budget. A sampling of key questions to explore include: How much look development time is required to achieve the specific style or art direction envisioned for the project? Does the style of the show involve developing a particular software program or proprietary tools? How many characters are in the main cast? Are there many crowd shots and how often are they needed? How many locations/sets will there be and what is their scale? How complicated are the camera movements? Are the props simple or complex or a combination of both? What kinds of special effects will be necessary, and will the project be effects-heavy? Are there songs? If so, how many and what is their purpose (that is, are there big production numbers or soliloquies)? And equally as important, how much reuse is possible?

Style/Art Direction and Design

The choice of art direction and design and how the imagery is generated through the selected animation technique has a direct impact on the production plan. Whether the style of animation is highly nuanced—rich and fluid versus graphic and stylized—also has an impact on the budget. In the best-case scenario, the look of the project is clearly established during the development phase. The producer can then evaluate the complexity of the artwork along with the number of assets to be built and create a schedule and a budget accordingly. Unless there is an agreed-upon style, the producer has no choice but to prioritize and allocate funds to resolve all outstanding stylistic questions in order to set the art direction for the project. For example, if the look desired is similar to Peter Jackson's and Steve Spielberg's The Adventures of Tintin: The Secret of the Unicorn, the feature will require a substantially larger budget than the type of art direction style of classic handdrawn animation as depicted in Sylvain Chomet's The Illusionist. (For more information, see Chapter 8, “Pre-production.”)

Average Number of Characters per Shot

Assessing how many characters are to be animated on a shotby- shot basis is also key to determining your budget, as it will affect the amount of time the crew has to spend on each shot and the quotas they can produce each week. Aside from crowd shots, does the story involve at least two or more characters in an average scene, or will the focus be primarily on one character? Equally as consequential is how much contact there is between the characters. For example, when characters come in contact in the CG realm, there are interpenetration issues that require more production time (either by an animator or a character effects technical director) to solve. Similarly, in 2D animation that involves hand-drawn frames, if there are two characters with no physical contact, the animation for both characters can be cleaned up concurrently by two artists and can therefore speed through the cleanup phase, whereas characters that have contact will be animated on the same level and will require more time as one cleanup artist must complete the task.

Part Two, Three or More

Kirk Bodyfelt, Producer, Sony Pictures Animation

Making a sequel to a successful feature film is a fun yet challenging task, as I discovered in my work on Sony Pictures Animation's Open Season 2 and Open Season 3. Right from the greenlight, the pressure to deliver a film that lives up to the standards established by the original project is immense. From storyline to performance to art direction, the bar has been set, and certain expectations arise within the audience; sometimes this pressure comes on top of the reality that the resources for a sequel are often significantly less than those of the original project.

The real trick is deciding what matters most to the audience, and making sure that you spend your budget on what is important (characters and animation), not on “bells and whistles” (complex effects, lavish production details). Maintaining a consistent look and animation style between the original and sequel production requires technical know-how. Even if the same studio is working on the sequel as did the original, the tool set used to create animated films—especially those in CG—is constantly changing. Unless a sequel is going into production immediately upon the completion of the original film (an unlikely situation), technology updates often require even the “reused” digital assets (i.e., the characters, sets and props that are returning, unchanged, to the sequel) to go through a complex procedural update so that they work within the new production pipeline. It is certainly less effort than creating an element from scratch, but it is a decent amount of labor that must be scheduled and budgeted for.

In many direct-to-DVD sequel scenarios, the budget is often limited for an in-house production and the sequel is sent to a subcontractor. Reaching or exceeding the established bar of expectations by the theatrically released feature film is doubly compounded when outsourcing a sequel to a different studio. In such a production, the director and creative leadership must work hard to help maintain as much of the original personality of the established characters and as much of the feel of the established world as they can within the parameters of the subcontract studio's pipeline. Most lower-budget animation houses do not have the luxury of proprietary tool sets and flexible pipelines but rather employ simpler, “out-of-the-box” software packages. Although this setup allows significant financial savings in terms of start-up costs and productivity, it invariably results in a decreased ability to match the exact look of the higher-budgeted predecessor. Compromises have to be made in order to work within this more limited pipeline.

One key advantage to doing a sequel is that you are working within an established universe. The real challenge, then, is the decision of how to expand upon the original film's plot in a comfortable yet refreshing way. Although it is important to present a fresh and exciting new storyline in a sequel, it is likewise important to maintain the same sense of character and attitude as the original film. When writing the screenplay, the filmmakers must constantly ask themselves, “Is this an action or line of dialogue we would expect from this character?” Ideally, the first film planted a handful of story points that naturally make sense to follow through in a sequel: taking a character relationship to the “next level,” dealing with a returning nemesis, or perhaps giving a popular minor character an expanded role in the continuing saga. For instance, at the end of the original Open Season, Elliot the one-horned mule deer has just won the affections of Giselle, the most beautiful doe in the forest. At the beginning of Open Season 2, Elliot's friends are throwing him a bachelor party in celebration of his upcoming wedding to Giselle. Much of the plot line focuses on Elliot's nervousness in committing to a marriage and how he eventually comes to realize that being tied down in a relationship is not necessarily a bad thing. In Open Season 3, we see that Elliot and Giselle are the parents of three children, and Elliot must learn how to balance family responsibilities with his loyalty to his friend Boog the bear.

Reading critical reviews of the first film and reviewing any audience reaction specifics that were collected (from a preview screening, for example) are also ways to make sure your efforts are focused on the right ideas and characters. This approach plays into the concept of being smart with how your overall budget is spent as well, if there are financial limitations to the project. Huge effects sequences, crowd scenes, and boatloads of new characters often will not fit into the budget of a direct-to-DVD release. It is better to realize this factor up front than to fall in love with a plotline that will later prove to be impossible to produce with the resources at hand. Conversely, acknowledging that character-driven stories with limited complex locations and props are much simpler to produce will provide a better chance of developing a plotline that is manageable with a reduced budget.

Like any live action counterpart, an animated film's sequel benefits greatly from having its original cast return. Retaining the same voice talent helps hugely in maintaining a character's personality and, subsequently, a sequel's feeling of consistency. However, due to scheduling and/or budgeting issues, the original actors may not be an option. Luckily, animation has the benefit of not relying on the visual aspects of an actor, so re-casting an actor with similar vocal qualities or a literal “sound-alike” is a possibility that works much better than re-casting in live action films. It is then incumbent upon the director to ensure that the replacement voice talent finds the right balance between delivering his or her own performance while projecting a vocal quality to satisfy the pre-existing fan base. For example, on the first Open Season film, we cast Martin Lawrence as Boog and Ashton Kutcher as Elliot. When it came time to do the sequel, neither actor was available to reprise his role, so the search for replacement voices began. Rather than trying to find generic sound-alikes, our goal was to find other established actors with similar voice qualities to the characters. After extensive searching, we ended up re-casting Boog with Mike Epps and Elliot with Joel McHale. Mike's deep, soulful, energetic voice worked great as the new voice of Boog, and Joel McHale's high-energy rants from his weekly television show The Soup proved he could be an excellent replacement voice for the wacky Elliot role.

Even after following these guidelines, you must step back, look at the plot on its own, and make sure that it is entertaining and fun, independent of character familiarity. A decent amount of your audience on a sequel has either not seen the original film or has forgotten most of the plot specifics from it. Through simple storytelling and crafty dialogue plants (“Remember last time when…”), you can help ensure that a sequel can stand on its own legs as an independent film.

Although lower-budget sequels are primarily created for the home entertainment market, there are sometimes opportunities for these productions to garner theatrical releases in the international market. As long as the final product is rendered at a high resolution, the images should be sharp enough to be projected in movie theaters if a theatrical run is merited. Open Season 2 and Open Season 3, which were conceived as direct-to-DVD productions from the outset, both had successful theatrical runs on big screens in Russia while also filling a notable number of small screens around the world. Our team couldn't be prouder of the work we did in making the most of those sequel opportunities and providing successful encores to the original film.

Production Methodology

Establishing a production pipeline or methodology from the outset is essential. The production process should include all of the steps to be taken and how they will be handled, including milestones, approval requirements, and point people. The technique used directly affects the methodology chosen as well as the staffing and technology support required. (See Chapter 9, “Production,” for further information on CG and 2D processes.) It should be noted, however, that some flexibility to step outside of this pipeline may be required on highly complex shots. For example, a stylized smoke pattern visual effect may be better hand-drawn and scanned than created in the normal CG software system. Whatever the selected technique, all parties involved should anticipate and facilitate a detour when necessary to support the creative vision while striving to adhere to the planned pipeline more often than not.

One of the first decisions to be made at this stage is whether the budget allows for completing all the production elements in-house or whether a partner studio is to be involved. In either case, the producer should determine a general crew structure, including the number and types of team members on both the artistic and administrative sides of the process to support the production methodology. On projects that will be outsourced, the producer should plan for fees and other costs associated with subcontracting such as pipeline compatibility issues. (For further information on subcontractors, see Chapter 7, “The Production Team.”)

Research and Development

On CG productions, it is important to allow time to complete tests for each unknown element such as new software or a challenging character design. Without such tests it is impossible to accurately determine what kind of talent and technology setup may be needed.

The next step for the producer is to assess what materials will and will not be produced in pre-production, because this sets up the flow of production. On features and direct-to-DVD projects on which budgets are higher, all design elements—including characters, locations, props, and effects—are typically designed in-house. On television projects, this is not always the case, as there may be some elements to be designed by the subcontracting studio (such as special effects and some props).

The Crew Plan

Based on the selected methodology, using the preliminary master schedule, the next step for the producer is to build a detailed crew plan. This plan is ultimately a scheduling and budgeting tool used by the producer to determine the number of staff members needed in each category. It includes the number of weeks it will take them to produce the elements they are responsible for, and it outlines their start and end dates. The crew information is also important for the producer in terms of figuring out office space requirements. Additional items contingent on the size of the crew include production equipment, software licenses, supplies, telephone systems, parking availability, office furniture, and fixtures. Similar to the schedule, the crew plan remains in flux until the budget is finalized and the production is greenlit. As a show moves through the production process, the crew plan will be revised and updated on an ongoing basis, as it is directly linked to the cost reports generated. Once the budget is signed off on, however, the bottom line figure remains the same. The crew number however, will be shifted based on the inevitable production challenges as well as the team learning how to use their time more efficiently as they get more familiarized with the show.

Prior to creating the budget, the producer needs to research salary rates. Salary information is drawn from a variety of sources. If a producer has worked his or her way up through the ranks, much of this information comes from a knowledge base regarding typical rates within the industry. Although an applicant's past experience and the demands of the job are key factors in determining a number, it is not always easy to come up with the right figure. Assuming that you have never produced before and you do not have access to a sample budget, you should consider doing a little investigative work. Don't be timid about picking up the phone and asking other producers. Due to confidentiality issues, they may not be able to get too specific, but their answers should enable you to establish a range. Once you have done your research, you will be better equipped to come up with a rate that reflects the current salary for the role in question.

If you don't know other producers who can help you with a rough idea, try to get a range from the potential employees themselves. You don't need to agree to a salary. You can gather the information and talk with your core team—specifically, your recruiter and/or human resources point person—to see if it is in the appropriate ballpark. Meanwhile, the Animation Guild has salary scale minimums that must be followed by the producer if the project is a union show in Los Angeles. (See the Appendix, “Animation Resources,” on the companion website for contact information.) In most cases, if the artist is experienced, he or she is typically paid above scale, and in some instances significantly more than the salary listed. In animation however—as in most industries—the rates are based on supply and demand. When the industry is booming, rates are inevitably at a premium. When it slows down, wages are adversely affected and decrease accordingly.

An important item that a producer should remember to plan for is overtime. Depending on the studio, overtime may or may not be paid. If it is paid, overtime is usually charged when weekly hours exceed the originally agreed-upon number. Anticipating long work hours, however, it is not uncommon for artists to be hired for 50- or 60-hour weeks. Because most projects get into a “crunch” or push time when overtime is necessary, money should always be allocated in each job category to account for this potential cost. A rule of thumb is that 5 to 10 percent of all applicable labor costs are overtime costs. It is common to place this money in an overtime contingency category. (See the section “Contingency” later in this chapter for more information.) Also, if the project is a union one, or if the state/provincial laws require it, the producer must allocate money for severance pay.

One final item to think about is buffer money in the area of staff hours. This money can be put toward ramp-up time as a production gets up to speed or to cover vacations and holidays. On long-term projects, production staff will need holiday time off—typically a minimum of ten days per year. Sick days should also be counted at an average of five days per year. These days are usually accounted for in the fringe added to the weekly salary. On such weeks, quotas may lag and a department may require alternative methods of making up the difference (such as freelance work or additional overtime).

Figure 6-8 Sample CG television special crew plan.

Figure 6-8 is a sample chart for a crew plan. It has been partially filled out for illustration purposes. It shows typical staffing categories and should be altered to fit the requirements of each project. The purpose of the crew plan is to illustrate the total number of weeks for each position and where they overlap. Each crew member's start and end dates and the duration of his/her job is shown as a bar graph.

The Level of Talent

It is wise to clarify the level of artistic and directorial talent that is expected on the project. The range in experience level and salaries between artists can vary drastically. It may be that the budget is set up so that a substantial sum of money is used on the initial production design, with the intention of creating a style that can be animated in a subcontracting studio without compromising quality. Another example would be to allocate funds and hire acclaimed animation artists but simplify the story so that the budget can withstand the high cost of the talent.

In terms of the voice track, the level of star talent to be pursued for the project should be established at the beginning so that it can be accommodated. A question to address at this point is whether the project can afford “A-list” stars (often considered valuable not just for their raw talent but also for publicity and marketing purposes) or whether lesser-known character or voice actors will fit the bill. In most cases, it is a combination of the two. Because the rates vary widely, this information needs to be reflected in the budget and the list of assumptions. Another item to calculate at this stage are the number of casting sessions anticipated, rehearsals (if possible) and recording days necessary. (See Chapter 8, “Pre-production,” for more information on voice tracks.)

The Role of Key Personnel

In certain cases, it may be important to define areas of responsibility. In television, for example, there are often many producers on a project. It is therefore useful to define the duties to be covered by each producer so that everyone is clear as to where they must focus. Perhaps one producer handles the writing, casting, and voice track and another (usually a line producer) is responsible for the creation of all pre-production artwork and management of the production process.

Beyond the category of producers, the assignment of responsibility is useful for the entire crew and can only help the production efficiency reach its maximum level. Clear lines of authority and communication are important in enabling the crew to perform at its best, avoiding common pitfalls and misunderstandings about what each job entails and where each title falls in the production hierarchy.

Creative Checkpoints

The producer must establish—with the buyer—the points at which they will review materials and give input before finalizing the schedule. These reviews are called creative checkpoints. Examples of creative checkpoints can include:

- Selection of the voice talent and composer

- Approval of script(s)

- Approval of storyboards, story reel/animatic

- Approval of main character designs

An efficient approval process is critical to the success of any project. The producer must clarify the purpose of checkpoints, establish how notes are to be handled, and allow time in the schedule to accommodate revisions or be ready to shift other segments of the production plan accordingly. (For a detailed list of creative checkpoints, see “The Producer's Thinking Map” in Chapter 2.)

Buyer’s Responsibilities

The producer should clarify up front the costs that will not be covered by the budget and the buyer will be responsible for. Examples of such overages include script or design changes after the buyer has already signed off; the decision to re-cast voice talent after the track has been recorded; the addition of new elements, such as a song; and the buyer's travel costs.

Payment Schedule

A payment schedule is a document that outlines when the buyer is to send funds to the producing entity. This schedule is negotiated and may be broken into monthly payments or percentages based on the achievement of milestones during production. Once agreed to, the production accountant prepares this schedule with input from the producer. It is based on information obtained from the budget and schedule and is not usually prepared until the budget is finalized. The producer should keep in mind that if the buyer resides in a different country, the exchange rate or a range should be determined right from the start whenever possible. This document should also take into account any international holidays that might delay the arrival of funds. When preparing the payment schedule, all costs for each month need to be indicated in a cash flow chart. This list must be itemized and should be inclusive of staff salaries in addition to any other fiscal expenditure anticipated for a given month. Once the numbers for all months are added up, the figure should match the grand total budgeted for the project. Whatever method of payment is determined should be outlined on the list of assumptions.

The Physical Production Plan

Once all of the previously mentioned steps have been worked out, the producer uses this information to plan for the infrastructure of the project. Understanding the methodology and the scale of the project, the producer should research overhead and facility costs, taking into account questions such as: What parts of the production will require in-house talent and what material can be generated by freelance artists who can complete their assignments online as part of a cyber studio? Is there a preexisting space available for the production? If so, it may not be necessary to purchase desks and other such equipment. If not, the producer must establish what items need to be purchased, built, and installed. While evaluating the production needs, the producer—in cooperation with the technology group—researches and selects the hardware and software required. For more information on the role of the technology group, see Chapter 4, “The Core Team.”

Training

If a project has special creative requirements, such as the use of a new software program or an innovative style of animation, it may be necessary to provide additional training for the crew. Consultants may need to be brought in or sent abroad when material is being subcontracted. These costs are most often allocated for high-end productions and should be provided for in the budget. (For more information on training, see Chapter 4, “The Core Team.”)

Recruiting and Relocation

The costs of recruiting and relocation should be included within the production plan and are directly affected by the state of the industry in any given location. Supply and demand drive the amount of resources required for this aspect of the budget. If there is a shortage of talent where the project is to be produced, it may be necessary to hire artists from other locations. In such cases, it is common to pay for airline travel, temporary housing, transportation, moving costs, and possibly a per-diem fee while in transit. Additionally, the production is responsible for obtaining visas and work permits when necessary.

Reference and Research Material

Depending on the scale of the production, this category may be minimal—that is, limited to Internet surfing or the purchase of a few books and DVDs—or it may involve the creation of an entire library with full-time staff. On feature productions, it is not uncommon to set up meetings for artists to meet experts or consultants and possibly get training in a specific field in order to lend more credibility to a project. If an animal is going to play a major role in the film, animators will more than likely be provided with an opportunity to get up close and personal—whether it is a lion or a falcon. Often times, field trips are set up for key production staff to visit a location similar to the one being recreated for the production in order to allow them to have firsthand experience in the environment. In all of these cases, the extent of reference material and research necessary must be analyzed from the start so that monies can be set aside for this purpose.

Archival Elements

Elements should be archived in case they are to be used for future productions, the creation of consumer product or bonus materials on DVDs, or possibly as potential revenue sources through auctions or gallery sales. It is critical that an efficient archiving system be in place—whether it is for artwork on paper, board, or digital files—so that these materials can be easily retrieved. The system should include clear demarcation of the artist's name and whether the element applies to an “in-picture” concept or one that has gone “out-of-picture.” The producer should clarify from the outset who will be paying for this process. In most cases, costs associated with archiving and storing the artwork are separate from the production budget and are paid for by the buyer upon the completion of production.

Physical elements to be archived include:

- Artwork on paper (such as conceptual work, designs, storyboards, and animation artwork)

- Any traditionally painted materials (such as backgrounds)

- Maquettes (physical models of characters) or practical set/prop models

These elements should be protected for historical legacy in a temperature controlled environment, and stored by using clean archival chipboard and other acid-free lining papers and organizers between the pieces. There should be no rubber bands, staples or stick-notes attached to the artwork, as these will degrade and ruin the preserved materials over time.

Digital files must also be archived for potential future use. Types of files that should be considered for archiving include:

- Visual development artwork

- Character and color models

- Story panels

- Pre-vis set ups

- Editorial cuts (from checkpoint screenings)

- Assets in different stages of geometry, rigging, texture

- Layouts/shot setup

- Final animation

- Final assets

- Final lighting

- Backgrounds and matte paintings

- Reference video

Keep in mind that because technology can change rapidly, some digital elements may not serve as functional assets through future software options. Innovations in software may actually make the recreation of elements such as models, rigs, and shaders a more efficient choice than trying to resurrect an older version, even when reusing the very same character in a sequel project.

Contingency

The contingency is a pot of money that is separate from the production budget. Typically, the amount ranges from 5 to 10 percent of the budget. Although it is advisable to have a contingency, not every production can afford this cost. For those productions that can, there are usually two main purposes as to when and how this money is spent. The first includes instances in which it is necessary to cover costs for unexpected production problems. The other is to cover the costs of creative changes that are above and beyond final and signed-off materials.

In terms of unexpected production problems, it is not uncommon for the pipeline to break down. Although producers try to do everything in their power to plan for all costs, there can be a multitude of unexpected issues that unfold and challenge a production. When unanticipated issues arise, the producer judiciously taps into the contingency money to cover the costs. An example of a situation warranting the use of the contingency is a project on which new processes are being tried, such as in a newly created CG production pipeline. In such a case, system errors can have a significant effect on the pipeline, forcing the production to shut down in order to solve the problems. A system shutdown can result in a loss of digital work and time in the schedule. If artists are unable to work due to computer malfunction, they must make up the missed time.

Although elements and materials are signed off on and finalized during production, the creative process cannot always be controlled. It may be that someone comes up with a fantastic idea that needs to be implemented and that could elevate the project to a higher level of quality and—hopefully—success. Perhaps what appeared to be a good read in script form is not working out as well when it is brought into the visual medium, requiring additional time and focus in the story department in order to solve issues that have become clear in the story reel. Or it may be necessary to re-cast a voice actor for a lead character. Under these circumstances, shots that were already animated may need to be reworked, and this work—along with re-casting and re-recording—can be costly. Another common reason for creative changes is audience or buyer feedback. If a show is tested and gets feedback that justifies re-examining certain creative issues, further refinements will more than likely be necessary. Shots may need to be added or deleted to clarify a key plot point, for example. The costs of unanticipated creative changes such as these must be covered, and in most cases the contingency is used for this type of expenditure. It should be noted that for most features, creative changes are anticipated up front as part of the process. The scope of the changes, however, is unknown, and therefore it is simpler to set contingency funds aside, knowing that they will be used for creative improvements throughout the production.

Depending on the budget of the project, the contingency can be a significant amount of money. The key to successful use and control of the contingency is to clarify up front the parameters surrounding its use. A system should be designed that defines who has the ultimate authority over spending the money and how approvals are obtained. In most cases, prior to spending any of the monies, the producer budgets the anticipated costs as closely as possible and how they will be spent to cover the overage. This breakdown is then given to the final authority—in most cases, the buyer/executive—for approval.

Building the Budget

Once all of the previously mentioned information has been gathered and a preliminary schedule and crew plan are in place, the producer can begin the task of building the budget. Budgeting is truly an art, as there are so many aspects to consider and balance in order to come up with an optimal plan. Figuring out the total amount for a budget is a methodical process. In some cases, a producer may be provided a target number by the buyer that is all-encompassing. In this instance, the budget should essentially be reverse-engineered to meet the desired number. In other cases, a producer is given nothing and therefore needs to do his or her best to determine the right number based on the estimated number of manweeks per department or the crew plan, the schedule and the list of assumptions.

There are two levels to a budget: summary and detail. The summary budget groups the line items into major categories simply to illustrate where the money is allocated from a macro point of view. On the summary sheet, for example, there is one line devoted to the “storyboard” category, and next to that is a sum total of costs for this phase of production. The summary budget is usually no more than two pages. The detail budget is further divided into labor for the category (i.e., head of story, storyboard artist, storyboard cleanup artist), supplies, equipment, and fringe benefits. Each item has its own separate dollar amount listed, with the sum total matching the number under “storyboard” in the summary budget.

Most budgets are divided into two sections: above the line and below the line. The above-the-line numbers are commonly those numbers based on contracts. These numbers include rights payments, options, royalties, and script fees. Also included are deals and payments to be made to producers, directors, and writers, as well as any other key talent associated with the project (such as actors). These figures are considered the creative costs of the production. The below-the-line items are all other monies required to produce the project, such as the crew, equipment, subcontractors, and so on. Such expenses are generally fixed in terms of what the production itself will cost in order to be completed. The distinction is made between the two categories because some of the above-the-line costs may be deferred. Above-the-line talent often participate in backend profits or have points (a percentage of the producer's profits after all other expenses are covered and investors repaid) or receive bonuses based off of box office success. It also makes it easier for executives to review the budget and assess the differences between the lead creative fees and actual nuts-and-bolts production costs.

The producer also needs to establish what the fringe benefits (or fringes) will be for the project so that they can assign these costs throughout the budgeting process. Fringes are those costs above and beyond the actual contracted or purchase price of an item. Standard items are guild and/or union pensions, health and welfare contributions, employer matching contributions, Medicare, unemployment taxes, and so on. Fringe rates must be paid. Depending on the studio, these rates can range between 33–35% of gross labor costs. The percentage charged for each individual item varies depending on the location of the studio, benefits provided, and whether it is union or non-union. Table 6-2 lists a number of standard fringe payments that must be tailored to the specific production.

Chart of Accounts

The chart of accounts is used as a base template for building a budget. Figure 6-9 shows an all-encompassing chart of accounts that can be utilized for CG and 2D (including traditional and digital) projects, plus costs associated with creating stereoscopic production. It lists line items—including personnel, equipment, and so on—to be budgeted for and their respective account codes (e.g., 0200 Producer's Unit). These account codes are also used by the production accountant and crew to assign and track costs for each line item within cost reports. Depending on the studio, there may already be a standard numbering system in place, or the producer may need to create or modify one. No matter how a project is produced, the purpose of having all items included in the chart of accounts is to remind the producer of all potential costs to be incurred on the production. As with all templates in this book, the producer should tailor the information to suit his or her particular production requirements.

Table 6-2 Sample Fringe Payments

| Employer Contributions | Amount paid by employer for employee’s taxes, withholding, benefits, etc. |

| Handling Charges | Fees paid to payroll services |

| FICA | Federal Insurance Contribution Act: Disability & Medicare) |

| FUI | Federal Unemployment Insurance |

| FUTA | Federal Unemployment Tax Act |

| SUI | State Unemployment Insurance |

| Workers' Compensation | |

| Health Insurance | |

| Pension | |

| Individual Account Plan |

There are different ways to create a budget. For example, you can build your own spreadsheets using software such as Microsoft Excel, or you may use one of many budget-specific software applications on the market.

Cost Reports

The production accountant, along with the producer, issues cost reports. Cost reports are a financial overview of the status of the project and how the numbers for each category are tracking in comparison to the original budget. Also referred to as variance or estimates of final costs (EFCs), these reports are used to evaluate the financial status of the budget on an ongoing basis. They are created from the final signed-off budget and schedule and are distributed to key personnel for evaluation. The weekly analysis of the cost reports enables the producer to efficiently navigate the production, shifting resources as necessary in order to facilitate the creative vision while keeping the project on track and on time. (For further information on accounting, see Chapter 4, “The Core Team.”)

Figure 6-9 Chart of accounts

Figure 6-9 (Continued)

Figure 6-9 (Continued)

Figure 6-9 (Continued)