Chapter 28

Commercial Production

INTRODUCTION

Similar to television and feature production in many ways, commercial production is very much a world onto itself. Though there are individuals who have the ability to jump back and forth between the two realms, many choose to build their entire careers within this fast-moving industry. Production schedules are much shorter, crews are smaller and salaries are generally higher. Much of the paperwork is different and studios and networks are replaced by advertising agencies and clients. Because of these differences and the fact that this industry is such big business throughout the world, I thought it was important to include a chapter outlining the basics of commercial production.

Because my experience in commercials is limited to one month of working on Kentucky Fried Chicken commercials many years ago, I’ve had to rely on others to help me with this chapter. It originally came together with the help of my neighbor and friend, commercial producer Christine Evey. But as Christine has been working in another end of the business for a while now, she referred me to her friend Ali Brown (head of production for PRETTYBIRD, a Los Angeles-based commercial production company), who graciously agreed to take on the updates for me. Along with the revisions Ali sent me, she included a theoretical note that I’m keeping in her own words, because they speak to this field of production and how it’s changing. Having gone through the usual career struggles while working in all mediums, Ali states:

“While commercials are often thought of as the least sexy compared to features and television — they’re often very lucrative and well-funded, which can, with the right client, engender great creativity. It’s a different challenge to tell a story in 30 seconds. However, now that commercial clients are not only wanting to produce traditional broadcast spots, but also web content as well as other deliverables, there’s a resurgence in creativity as companies struggle to tell a story while balancing a reduction in what were once very inflated budget with a new found freedom in format and time. And it must be remembered that directors such as Spike Jonze, David Fincher, Michael Gondry, Wes Anderson and Spike Lee all enjoy very successful commercial careers.”

A commercial starts with a client who hires an advertising agency to promote their product or service, and the agency decides to include at least one commercial spot as part of its advertising campaign.

DEVELOPING, BIDDING AND AWARDING

The following is a brief rundown of the process from inception to the beginning of pre-production:

• The agency’s traffic department purchases air time for the commercial spot(s).

• The agency’s creative director assigns creative teams, each composed of an art director and copywriter, to come up with concepts for the spot(s).

• An account executive is assigned to the project. This person becomes the primary liaison between the client and the agency.

• The creative teams meet with the client to pitch their concepts. Some ideas are rejected and others are developed further before one is finally chosen.

• An agency producer is assigned to the job, and he or she will confer with the art director and copywriter in narrowing down a selection of commercial production companies and directors who might be right for the this type of spot. Production companies can employ anywhere from three to over twenty different directors in some cases; some of the more successful commercial directors have their own production entities.

• Once commercials are approved by the client, the creative team(s) and agency producer confer regarding what type of director they’re looking for, coming up with a potential list of those they’re interested in.

• Also at this point, a pre-bid meeting typically occurs where a ballpark bid is shared with the client, estimating the budget that can be allotted to the project — inclusive of production costs, talent costs, post production costs and agency travel.

• The agency producer then contacts either the executive producer of the production company the selected directors are attached to, or the sales representative (covering their region) for the production company. Requests are then placed for the directors’ demo reels.

• The creative team(s) and agency producer review all the reels, narrowing it down to what they call the “short list.”

• After director’s availabilities are confirmed, scripts and storyboards are sent to the production companies/directors whose reels are liked in the hope that the directors will be interested in the project.

• If all parties are interested, the agency will then decide on which directors they want to “bid.” Typically, three directors are invited to bid the job, but sometimes, the bid list can extend to five or six. In some instances, a director is “single bid”usually if he or she is the incumbent on a project which has been successful in the past, or if the creative is particularly suited to one director’s visual or technical style.

• A conference call is set up between the director and the agency creatives allowing the creatives to share their original concept with the director and to hear the director’s approach on its execution. After this initial call, the director is asked to submit a written approach outlining in detail his or her specific take on the creative concept. Many times, visual references to locations, casting, lighting or overall tone are submitted along with the written approach to what’s commonly referred to as a “director’s treatment.”

• Simultaneously to the creative approach being thought out, a production approach and budget is being determined as well. Once the initial conference call has been completed, the agency producer will send a bid package to the production company. This package typically consists of a schedule, final creative scripts and boards and bid specs (known as PIBS in the UK). The bid specs outline in detail who’s expected to cover specific costs in the budget — what the agency will provide, what the production company should estimate for or a subcontractor (such as a post house) will be responsible for.

• An estimate is not only a line-by-line summary of costs (including sections for labor, pre-production expenses like casting and location scouting, location fees and associated costs, props and wardrobe, art department, equipment and film costs), but also an overall outline of how the production company plans to execute the job. Within the estimate, it’s determined where the shoot will occur (whether on stage, location or both), how many days the shoot will last and how long each shoot day will be. On top of each estimated cost is a production fee, commonly referred to as a “mark-up.”This number encompasses overhead costs as well as the production company fee. Because it’s an average that provides for differentials of profit and overhead throughout the job, the bid form is designed for use with a constant number in marking-up all line items of the bid.

• Typically, the director’s treatment and bid are submitted simultaneously to the agency producer. The agency producer shares the treatment with the creative team, so they can determine their creative recommend, while the agency producer and business manager review the bid. (A creative recommend is the director that the agency feels, based on the treatment and conference call discussion, has creatively offered the best approach for bringing his or her concept to life. At times, it’s the person they feel has most closely understood their vision; at other times, it’s the person who they feel has offered the most unique perspective, or a twist they hadn’t thought of. When presenting to their client, the agency will typically present the director they want to recommend creatively, and then try to make the financial aspect work, regardless of whether they had the lowest bid.) More conference calls ensue and bids are sent back and forth for budget clarifications. Recently, it’s become common for the bid to be submitted to a thirdparty cost consultant, typically hired by the client. This cost consultant goes through the bid line by line in an attempt to bring the budget down based on what they feel are reasonable costs. Often times, up to 100 questions may be submitted back to the production company, asking them to explain the logic behind the dollar amount they’ve assigned to a particular line item. This can be a very tedious part of the process, and many would argue that it’s an unnecessary one, as there are certain standards in the commercial industry that don’t necessarily translate to a traditional corporate approach to business. However, as clients need to control spending and increase profits, it’s becoming an increasingly common step.

• The bid specs will also indicate if this is a “cost plus” job or not. Cost plus is when the agency only pays for actual costs. This can apply to the overall budget or to specific line items — most frequently, pension and welfare costs on crew. If the entire job is cost plus, it works like this: production companies provide an estimate of costs based on the agreed upon specifications, and this estimate is submitted on a cost summary form. A fixed fee (a specific dollar amount) is then added to the total cost. When agreed upon, the combination of costs and fee becomes the contract price. At the conclusion of the job, the production company does a cost accounting, and the agency is billed for all actual direct costs plus the predetermined fixed fee. This way, additional costs for approved overages are added to the final payment, and if the job comes in under budget, the final payment is reduced by the amount saved. Even if the entire job isn’t deemed cost plus, certain budget items (generally those where the cost of unknown factors cannot be anticipated in advance) can be negotiated as cost plus during the bidding process.

• Once the creative team decides which director will be their creative recommend, the agency producer must also see which company has offered the most competitive bid. It used to be standard practice that the creative recommend would be awarded the job, but many clients are now also putting heavy emphasis on which company is offering the best value. Both of these factors are weighed heavily in determining which director will ultimately be selected. The advertising agency will meet with their client to discuss their recommended director, but ultimately, the client has the final say in which director is awarded the job.

• Once the job is officially awarded and the details of an approach have been agreed upon, the approved budget becomes the contract price for the job, barring a major change in specifications.

• The production company chooses a line producer to oversee the job, someone who receives the budget, script, storyboards and any other information pertinent to this job. (Line producers are typically freelancers, although some companies do have staff producers.) Once a job is awarded and handed over to the line producer, he or she will then assemble a production staff consisting of a production supervisor, production coordinator, a couple of production assistants and department keys. Unlike features, commercials don’t use the term “production manager,” as it’s a union category. Instead, “production supervisor” is the term used, although the duties are similar.

• A casting director is hired, a location scout starts lining up potential location sites and the pre-production process has begun. Shooting crew sizes range from 35 to 75, depending on the complexity of the job.

THE PRE-PRODUCTION BOOK

One of the production coordinator’s responsibilities is to assemble a pre-production book in time to pass out at the pre-production meeting. The book contains the following:

• A personnel list, including client, agency, production company, editorial, dailies and lab contacts

• A calendar that indicates prep activities (meetings, casting, fittings, scouts, etc.) and all pre-light, construction, shoot and strike days — also a general post schedule provided by the agency producer

• The script

• All storyboards

• The director’s shot list, or, more commonly, shooting boards

• Wardrobe and art department references

• A cast (or talent) list, including photos of cast members

• Location information with maps

• A crew list

• A vendor list (or “production directory,” as it is sometimes referred to)

• Anything else that is pertinent to the spot or location where it is shooting.

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE CLIENT, THE AGENCY AND THE PRODUCTION COMPANY

The following diagram illustrates how the client, agency and production company (ideally) relate to each other. The arrows indicate the individual each person primarily looks to for information and support.

FIGURE 28.1

Video village is an area on the set where the client(s) and agency people view all on-camera activities from video monitors.

DIFFERENCES

There are certain aspects of commercial production that are the same and others that vary from those of long-form productions. Here are a few key areas to be aware of:

• Depending on the variables involved, prep schedules can range from five days to two weeks. The number of shoot days can range from one day to one month, and wrap is generally two to three days in duration.

• In addition to signing with the Association of Independent Commercial Producers, commercial companies sign specific commercial agreements with the DGA, the IA and the Teamsters. Though most companies produce union commercials, there are some that operate under nonunion arms as well.

• Although the production is responsible for casting, booking, fittings, issuing calls and making sure contracts are signed, it’s the agency that signs with the Screen Actors Guild, not the production company. Sometimes, though, if an agency isn’t SAG-signatory, the talent used will be nonunion, and the production company is often asked to assume those salaries in their budget.

• Every production must be covered by general liability insurance. Most production companies carry insurance coverage, but there are times when the client will have insurance they can provide, saving on production costs. Who’s responsible for carrying the insurance varies on every job and is always confirmed prior to shooting.

• Any part of a visual effect that’s handled practically incamera becomes the responsibility of the production. Any CGI work or effects that are done in post are handled by the agency unless they’ve asked the production company to subcontract the post. Often this is done if the visual effects approach is intrinsically tied to the director’s approach, or if it’s a lower budget job, and the agency wants the production company to handle all aspects of the production to save on expenses.

• The production company pays for film processing and the development of dailies. Typically, the negative is then turned over to the agency; and the agency is responsible for the editing process. However, as stated earlier, on occasion the production company will handle the job through final finishing.

• Call sheets are much simpler than those used on theatrical or television productions (sample included at the end of the chapter), and with the addition of out times and pertinent notes relating to the day’s shooting activities, the same general form is used in lieu of a production report.

• Unlike a feature, television or cable show, the production supervisor is responsible for tracking all costs. At the completion of wrap, he or she submits a complete financial accounting to the production company by way of a wrap book (see the following section). The payroll is handled by a payroll company, and the accountant’s prime responsibility is to issue checks and audit the wrap book.

THE WRAP BOOK

A wrap book includes the following:

• Wrap notes, which give an overview of the job—how much film was shot, whether any accidents occurred, the current location of the negative along with shipping instructions, to whom wardrobe and props were dispersed and any other details that help create a one-page overview of the job.

• A final actualized budget showing the expenditures on the job as compared to the original estimate.

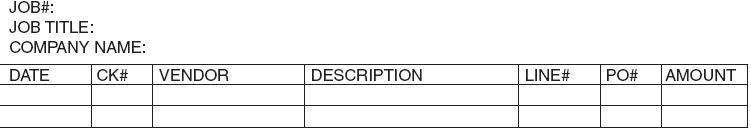

• A P.O. log and copy of every purchase order issued along with the backup invoices and receipts. The P.O. would look something like this:

PURCHASE ORDER LOG

FIGURE 28.2

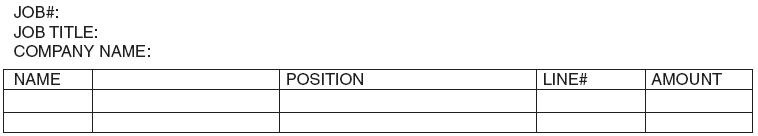

• A location check log, which looks something like this:

LOCATION CHECK LOG

FIGURE 28.3

• A payroll breakdown, which looks like this and include copies of all time cards, deal memos and kit rental forms behind it:

PAYROLL BREAKDOWN

FIGURE 28.4

• Petty cash reconciliations and copies of petty cash envelopes

• Talent contracts

• Location contracts

• Any additional information for insurance claims, accident reports or prop/wardrobe dispensation/inventories

The commercial industry in the United States is governed by the Association of Independent Commercial Producers, which focuses on the needs and interests of commercial production companies. Founded in 1972 by a small group of television commercial production companies, today’s organization represents the interests of U.S. companies that specialize in producing commercials on various media—film, video, digital—for advertisers and agencies. AICP members account for 85 percent of all domestic commercials aired nationally, whether produced for traditional broadcast channels or nontraditional use. With national offices in New York and Los Angeles and regional offices across the country, the association serves as a strong collective voice for the $5 billion-plus commercial industry. If you would like further information on AICP guidelines, labor information, contracts and riders, seminars, payment schedules, grievance procedures or forms, visit their website at www.aicp.com.

Many thanks to Ali Brown and Christine Evey for their help with this chapter.

FORMS IN THIS CHAPTER

• Commercial Call Sheet