12. Electronic Exchanges and Trading: Challenges

As with any innovations, challenges are introduced or exacerbated by electronic exchanges. Greater speed and globalization mean that there is less room for error and problems can instantly spread around the world. For all its advantages, technology is still rather fragile and unreliable. People are still prone to error and bursts of panic. The result can be greater volatility and, sometimes, ad hoc resolutions to glitches in the electronic infrastructure.

Change is never without challenges. The transformation of financial markets has had its share of bumps and hurdles. An emotional attachment to floor-trading has been difficult for the exchanges and the financial community to overcome. The move to electronic trading meant that it was losing a way of trading that has defined global financial markets for over a century. In addition, there have been challenges such as losing some of the jobs that were unique to financial markets and learning to adapt to new technologies to make a living in the new trading world. There have also been challenges unique to the world of technology that would never have occurred in the floor-trading model. Exchanges continue to upgrade their systems to keep up with growing volumes. Exchanges new to electronic trading continue to struggle with the speed and reliability of their electronic infrastructure.

The exchanges have dealt with numerous technology hurdles as they migrated from the floor-trading model to the electronic trading model. The ease of listing products has allowed exchanges to compete with each other for liquidity. Multiple listings of the same products on different exchanges have raised concerns of fragmentation. The transparency and speed of electronic trading have brought new levels of volatility in the marketplace. New trading styles have brought new challenges, some of which have been large enough to bring trading to a standstill or to jeopardize the survival of a firm. As the dependence on technology increases, the markets will continue to face these challenges.

Although the electronic trading model prevailed, the new world is far from perfect. The financial markets have weathered some major issues throughout the transformation phase. The exchanges have faced severe technology failures, bringing down the entire exchange for hours at a time. As the financial community transitions toward electronic trading, it has made some costly errors that have impacted entire trading firms and, at times, the wider trading community. There have been some memorable glitches by both exchanges and trading firms. Some of these have been isolated to just a few players; others have brought down an entire exchange. And in a market that has fought change for so long, any mistake, big or small, is put under the microscope. Any slip gives the skeptics new ammunition to challenge the electronic trading model and its viability. Markets today are far more competitive, and in this competitive world one cannot afford to make mistakes. As the financial community continues to transform its business model to adopt electronic trading, it will continue to face new issues. The exchanges will need to continue to enhance their technology to meet the challenges of growing volumes and increasing market share. The financial community will need to adapt to the new risks it faces in the world of electronic trading.

Dependency on Each Other

The world of electronic trading brought the speed, reliability, efficiency, and growth to financial market that would have been unimaginable in floor-trading. The new model, as we have seen, is far more complex and interdependent than its predecessor. Modular exchanges made it easy for the exchanges and the trading community to pick and choose components for the trading infrastructure offered by software application providers and other exchanges. The exchanges and trading community rely on technology providers for connectivity to the financial markets. Trading firms rely on vendors and brokers for their electronic platforms. Brokers rely on vendors to provide exchange connectivity. The exchanges, trading firms, vendors, and brokers all rely on telecommunications players such as MCI and AT&T, which provide the telecommunications infrastructure between these industry players. All these participants rely on disaster recovery and hosting solutions providers such as Equinox and BT Radianz. The financial markets are truly interconnected. The shared dependencies have brought many advantages for financial market players, such as cost savings, messaging standardization, and trading speed, to name just a few. This dependency has also introduced new challenges. Technology glitches at these external vendors can potentially have widespread impact on the overall financial markets. Outages at a single firm, technology provider, or exchange can bring down numerous other players.

Technology Glitches

As we have seen, technology is now an integral part of financial markets. Today every step of the trade cycle passes through computers and networks. All technology can fail. Computers and networks are hardware devices that do not have infinite lifespans. They will fail at any time without notice. The electronic trading architecture is built on software programs that communicate with each other. These software programs will have bugs that cause applications to behave abnormally or to fail. The network connections between computers and companies can be overloaded with message traffic. Whether it is a machine failure, a bug in a software application, or a capacity issue in the system, these glitches can have a significant impact on the financial markets. In its short history, electronic trading has seen systems fail, bringing down exchanges for anywhere from a few minutes to several hours and exasperating traders around the world. Exchanges with systems unable to cope with growing volume can add significant latency to order execution and market updates. As we will see, the financial markets have seen the widespread impact that a glitch in one single application can cause. Technology glitches in software applications have caused significant swings in the markets. Software bugs have caused erroneous trade execution and incorrect market updates, bringing a new era of out-trades. Over the last few years we have seen technology issues that have virtually disconnected individual trading firms from the trading world. These failures have caused both financial and reputational harm to the individual players suffering from these technology glitches.

Exchanges today spend significant amounts of time and money to build a robust trading infrastructure that can support the growing volume and growing number of traders. The software players spend tremendous amounts in research and development to build innovative tools and to provide robust and reliable applications to their customers. The trading community today measures exchanges not only by the product suite offered but also by the stability of its systems.

Exchange Outages

Since the exchanges began their journey of transformation, they have faced many challenges in building a reliable infrastructure. For exchanges today, their technology has to work seamlessly. Any outage has a direct impact on the trading volume on the exchanges. An unreliable exchange could literally lose liquidity and significant market share. In addition, due to the modular exchange model and interdependence between vendors, a failure on one exchange could have an impact on other exchanges halfway around the world. Over the last two decades, a number of exchanges have faced outages lasting from a few minutes to a full day. For example, Euronext's Paris-based exchange suffered over 10 trading suspensions in 2002 alone. By comparison, DTB suffered only one outage on April 16, 2002. 1 And in today's competitive world, these outages can be dreadful.

Some Major Exchange Outages Around the World2

Nasdaq, December 9, 1987

Nasdaq's systems in its data center in Connecticut were brought down when a squirrel climbed into the main electrical power line with a piece of aluminum foil. It was not a happy end for either the exchange or the squirrel. The exchange was down for almost the entire day and the squirrel was electrocuted.

Nasdaq, Summer of 1994

Nasdaq suffered several problems with its trading system in the summer of 1994. The system was down once again when a different squirrel chewed through the power line in Nasdaq's data center in Connecticut.

LSE, April 5, 2000

A severe computer malfunction brought the entire exchange to a halt. The exchange remained closed for approximately eight hours, preventing traders from bailing out of one of the busiest trading days. It was the end of the financial year, when many traders adjust their trades for year-end profits and losses.

NYSE, June 1, 2005

TSE, January 18, 2006

The exchange suffered its first closure in its 57-year history. Although it had suffered technical issues since going electronic, this was the first time the entire exchange was shut down. The Tokyo Stock Exchange was closed during the peak afternoon trading session. But this was certainly not the last time. The most recent closure was in July 2008, when a software bug caused the exchange to suspend trading between 9:21 and 11:00 in the morning session and 12:30 to 1:45 in the afternoon. 5

LIFFE and Its System Issues

As one of the early entrants in electronic trading, LIFFE has had time to improve its electronic trading infrastructure. With any new launch, people expect problems to occur. Therefore, the technical issues in the early stages were easier to tolerate. There were few competitors and even fewer people in electronic trading. However, even in those early days, any outages were noticed since traders made their living trading these markets. And traders are not very patient people. So an outage of even a few minutes is bound to create many unhappy traders. In 2001 alone, LIFFE suffered more than six different outages that brought its entire trading system to a screeching halt. For example, the system was down due to technical issues on August 23, and the exchange was forced to halt trading in Gilt futures, sterling interest rate futures, Euro interest rate futures, swap futures, and U.S. stock index futures. 6 In December 2006 it suffered an hour-long outage that once again brought down its trading system.

In June 2007, LIFFE suffered one of its biggest outages since 1997, the year when it launched LIFFE Connect and completed its transition to electronic trading. 7 The exchange was forced to shut down its operations from 7:00 a.m. to 11:00 a.m. when the exchange monitoring systems broke down. The exchange officials noticed an issue with the Connect tools that it used to monitor and control the markets. The markets are automatically opened at 7:00 a.m. When the issue was identified, the exchange moved to delay the opening of the exchange; however, by the time the system halt was implemented, some trading had already occurred for some of its big products, such as Euribor, 8 UK Gilt, and CAC 40 Index. Trading in Euribor and UK Gilt9 was open for 21 seconds and almost 20 minutes for CAC 40 Index. 10 All the orders submitted for these products were canceled by the exchange. The exchange system was fully operational at 11:30 a.m. (London Time), almost four and a half hours later than its usual opening hour.

LIFFE has had a history of outages and system failures. Although the exchange issued an apology and moved to reassure its customers that the issue was identified and resolved, the exchange's reputation for system stability and reliability suffered significantly compared to LSE, which had not suffered a single outage in its seven-year-old technology, SETS. Of course, as we will now discuss, with its move to a new-generation technology platform, LSE suffered one of the worst outages in the financial markets as well.

Seven-Hour Outage at LSE

On September 8, 2008, London traders were bracing for one of the biggest rallies in a market that had been in a downward spiral for quite some time due to the mortgage crisis, which had almost brought the global financial system to its knees. The U.S. government had stepped in to rescue Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae to help ease the tension in the financial markets. London traders were ready for a busy day. They got a glimpse of the busy trading when over 270 million shares exchanged hands in only the first hour of trading, compared to 617 million traded in the previous day. 11 At approximately 9:00 a.m., LSE announced it was shutting down its trading system when it noticed connectivity failure between the exchange and several brokers. The traders were unable to connect to LSE's 15-month-old trading system, TradeElect, a proprietary trading system that promised to provide faster round-trip order execution and expanded capacity to handle the growing volume. Trading was not resumed until 4:00 p.m., 30 minutes before the official close. It left hundreds of traders on LSE out of the trading activity for almost the entire day.

On a day that would have seen some significant trading, the LSE system came to a complete standstill. For the next seven hours the traders could not trade a single product on LSE, and the exchange volume took quite a hit. Shares of bank stocks such as Barclay, HBOS, and Lloyds TSB listed on the LSE traded 30%, 31%, and 21% less than their past three-month daily average. By comparison, bank stocks listed on other markets such as UBS AG and Deutsche Bank AG saw their volume double that day compared to their past daily average volumes. The LSE traded a total of $7.5 billion worth of shares, which was only about half of its usual volume. 12 The FTSE-100 was trading 200 points up an hour into trading when suddenly the traders could not route orders through the LSE trading platform. And for the next seven hours thousands of screens connected to the LSE trading platform were frozen with the FTSE 100 stuck at 5440.2, up 199.5. 13

For the LSE this was only the second major incident since 2000 that kept traders out of the market for over eight hours. The occasional system glitches are expected and reluctantly tolerated by traders, but this recent outage could not have come at a worse time. The LSE had been fighting to remain independent while other exchanges were merging to increase their market share. And new alternative trading systems such as Chi-X and Turquoise were arriving. Only a year old, these two trading platforms offered high-speed trading platforms at low cost, something the trading community, which had been increasing its use of automated trading, gravitated toward. If these system reliability issues continued on the LSE, trading platforms such as Chi-X, which already claimed to have 13% of FTSE 100 volume, 14 would most certainly pose a more formidable competitor to the LSE. Although this particular outage did not provide a significant boost to the trading volume on these other two electronic trading platforms, it was primarily due to both systems being fairly new, and few trading firms had signed on to trade on these platforms. Outages such as these made the new electronic trading platforms a possible alternative for trading firms that were virtually idle for most of this trading day.

LSE Outage Impacting JSE

Exchanges today utilize each other's technology for various trade cycle components. Problems on one exchange can impact another exchange if they are sharing technology. And that's exactly what happened on September 8, 2008. The connectivity issues at the LSE, which brought the entire LSE trading system to a halt for most of the day, also shut down the JSE in Johannesburg, South Africa, for most of its trading day. The JSE uses the LSE electronic platform, TradeElect, for its trading activities. The platform is hosted in London at the LSE data center. So the computer glitch in the LSE impacted JSE. Traders on JSE were also left out of the busy trading day, since JSE depended on LSE's platform and infrastructure.

CBOE: Floor-Trading Continues Amid System Issues15

One of the leading U.S. options exchanges, the CBOE has been late to the electronic trading party. Just like NYSE, the CBOE took a cautious approach to electronic trading. It still maintains its floor operations for options trading; however, the majority of its trading now flows through its hybrid trading system, launched in 2003. As described in a previous chapter, this system allows CBOE customers to route trades through the CBOE's hybrid system, CBOEdirect, or to continue to trade on the floor. The intention of the hybrid system is to provide an integrated market, which includes both the floor-trading quotes and electronic trading. Today over 92% of the CBOE's orders flow through the electronic system; however, 45% of the trading volume still occurs on the floor. Nevertheless, the impact on trading volume was certainly apparent on November 10, 2006, when the CBOE's electronic system suffered technical issues. The system was unavailable to the trading community from approximately 12:00 p.m. EST until the end of the trading day16 on Friday. The CBOE Futures Exchange (CFE), 17 which is fully electronic, was also unavailable for the remainder of the day. Trading for the CBOE was only available on the floor, which remained open for the entire day. Although floor-trading was available, the CBOE volumes were lower than the previous day. Approximately 1.8 million options were traded, compared to 2.8 million on the previous day. The trading firms for the U.S. options markets have alternatives. The firms using electronic trading platforms can route orders to exchanges such as the ISE or Philadelphia Options Exchange. And the competitor exchanges saw an increase in their volumes as a result of the system outage at the CBOE. However, the trading firms had no alternatives for contracts such as S&P 500, which is exclusively listed on the CBOE. Trading of the S&P 500 was significantly lower than the daily average volume. On Friday, approximately 225,000 contracts exchanged hands compared to daily average volume of 430,000. The lighter volume is certainly an indication of the increasing reliance on electronic trading by the financial community. So even though the floor was open for trading, the exchanges logged lower trading volume.

The Impact of Real-Time Data Availability

Data on trading activity, market events, and company news is available in real time to anyone with a computer and Internet connectivity. Firms such as Bloomberg and Reuters built their business by consolidating financial data across financial markets and providing it to traders in real time. Not only does Bloomberg, for example, provide traders with the prices and volumes of all trades for global exchanges, it also collects and displays economic news and company-specific news. Traders rely on this information to make their trading decisions. Technology has made it easier and faster for users to receive this information, helping them react to market events faster and adjust their strategy, thus minimizing potential trading losses.

As we saw earlier in this chapter, computers are not perfect, and failures in systems can have a significant impact on trading. Today trading firms rely on technology to get market data and other financial news throughout the trading day. Incorrect or missing information can be costly. The recent plunge in United Airlines' stock was a prime example of such a glitch.

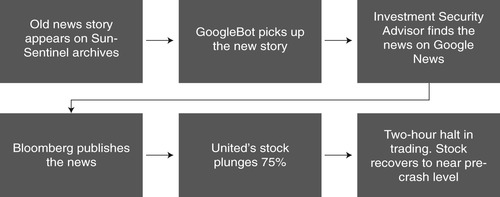

On September 8, 2008, United Airlines' stock plummeted almost 75% in just a few minutes until trading was manually halted by the exchange. The series of events leading to this plunge was astonishing and shows how information flow can have dire impacts on trading (see Figure 12.1). It started when Google News18 grabbed a story from the South Florida Sun-Sentinel about United Airlines' bankruptcy filings. The story grabbed by Google News was, unfortunately, an old link to a story on United's bankruptcy that was originally published in 2002. The article had no publication date, so Google News applied the search date to the publication when it posted the story. This old link was picked up by the Income Securities Advisor, which scours the Web to find stories about distressed companies. The news story was then distributed to Bloomberg. The news instantly reached every computer that subscribed to the Bloomberg newsfeed. 19 All of a sudden an old bankruptcy story from 2002 emerged six years later as a breaking news story in 2008. When an 11:02 a.m. Bloomberg headline was posted: “UAL Corp., United Airlines, Files for Chapter 11 to Cut Costs,” the airline's shares plunged from $12 to $3. A minute later, at 11:03 a.m., another update on Bloomberg: “Shares Fall Following Headline of Chapter 11.”20 Trading was halted by the exchange to investigate the sudden drop. Though the stock eventually recovered and closed that day at $10.92, it was not without significant losses for some traders and reputational harm for United Airlines and the numerous parties involved in this chain of events.

Although the stock recovered as fast as it fell (see Figure 12.221), these glitches remind the trading community that the impact of such mishaps in electronic trading, where news travels fast and is accessible to the entire financial community, can be costly for company stock as well as the traders who reacted to the news event.

Market Volatility

Exchanges around the world are completing their migration toward electronic trading. The trading community is getting accustomed to the availability of real-time data and the trading applications used to route orders. So far we have seen technology glitches that cause system outages and halt trading on an exchange. And we have seen the impact incorrect data has in a real-time trading environment. One of the other major impacts of technology is the potential volatility in the market that can be caused by system latency and capacity issues. As we will see, these issues are not due to actual failures in the system or inaccurate information. Instead, it's a potential delay in data dissemination that can make the market appear to be far more volatile than it is. In the automated trading world, traders build algorithms and strategies specifically to react to large volatility swings in the markets. If the volatility in the markets is caused abruptly due to capacity issues, it can trigger unwanted orders that can be costly to the trading community.

Sell-Off due to System Issues

The Dow suffered significant losses on February 27, 2007. Market events, such as the uncertainty about the U.S. economy and declining global stock markets, caused traders to be on edge. The NYSE saw a significant increase in the total volume traded on the exchange. Their computer systems were unable to keep up with the increased volume. As trading increased throughout the day, the NYSE messaging system began slowing down. Trades began queuing in their computer system, which means that it was taking longer to post messages. In other words, the market data on the traders' computers screens was delayed without them realizing it.

When the exchange noticed the system performance issues, it switched to its backup system. Once online, the message traffic caught up and within a minute the Dow saw a plunge of 178, and over 240 in less than three minutes. 22 Traders panicked, which triggered a larger sell-off. Although the over-400-point decline was accurate, it actually occurred over the course of an hour, not in just three minutes, as reported when the systems caught up. A sudden market plunge is never good in a volatile market. A 178-point drop over the course of an hour is different than if it happened in a minute. The market has time to react and time to absorb the reasons for the drop. A sudden drop leads to rumor, panic, and fear. The trading decisions are usually very different for markets with a sudden drop versus a gradual drop.

The market volatility in the months of September and October 2008 is something most people in the financial market will not forget for quite some time. It had been a painful time that tested the patience of even the toughest traders. The mortgage crisis brought the U.S. economy almost to a standstill and required a massive bailout from the U.S. government. Plenty of records were broken. The U.S. equities markets saw one of the biggest point drops when the Dow dropped 777.68 on September 29, 2008, wiping out almost $1.5 trillion in market value. The following two days saw a 600-point reversal. These wild swings in the market caused by the large volume of trades tested the computer systems of the NYSE.

Short Selling23

Although no companies were spared in the tremendous sell-off in September 2008, the financial sector was the major victim. Almost every bank stock suffered significant declines. Financial stocks were in a downward spiral for a few weeks, and some thought the cause was short sellers. To prevent further declines in these stocks, regulators implemented a temporary ban on short selling on 799 financial companies, 24 which went in to effect on September 19, 2008. 25 The changes were implemented in the electronic systems and enabled the financial markets to comply with the new rules overnight. At the beginning of trading on Friday, the exchanges noticed trades executing at very odd prices. Some of the trades were executed at more than double their closing price; others were as low as a penny. Almost every electronic trading system saw orders executed at these odd prices, causing the exchanges to cancel thousands of orders and leaving some traders with unexplained losses.

The electronic exchange systems are set up to accept a wide range of bids and offers. These trades are executed when the bids and offers are matched. On the surface there doesn't seem to be an issue; however, the exchanges noticed the unusually wide range in bids and offers26 that were being submitted by electronic trading systems. The exchanges blamed the issue on the initial confusion about the rules surrounding the ban as well as on high trading volumes. The exchanges moved to cancel all trades that traded 20% above or below Thursday's closing prices. Thousands of trades, a much larger number than usual, executed on the NYSE ARCA, Nasdaq, BATs Trading, and DirectEdge were canceled. NYSE Arca alone canceled approximately 30,000 trades. As we will discuss later in the chapter, if the exchanges notice an incorrect or invalid trade, they can automatically cancel it. However, in this situation, not all trades were clear cut, and many trades were deemed valid by the exchanges and left traders with some significant losses.

Another Erroneous Trade, Another Volatile Trading Session

September 30, 2008, will be remembered by many traders who traded Google stock. A data glitch caused an erroneous trade from another exchange to flow into the Nasdaq trading system. 27 Shares of Google stock were trading in the range of $395–420 for most of the day until the close of the market, when suddenly the stock dropped almost 93% in the final minutes of trading. The stock price swung wildly, reaching prices as low as $25. The price bounced back quickly, but the price fluctuations continued. The stock traded in the range of $320–488 for the remaining five minutes until the closing bell. The exchange quickly announced that it was investigating the erroneous trade that caused the unexpected price drop. After a review, it was determined that an erroneous transaction was submitted and drove down the price, causing artificially low bid and offer prices. Nasdaq canceled all trades above $425.29 and below $400.52 that were executed between 3:57 and 4:04 p.m. EST. The exchange adjusted the closing price for Google shares to $400.52, updating the inaccurate original settlement price of $341.43.28. and 29.

Inefficiency: Out-Trades in the Electronic Trading World

As we saw in our examples, errors in trading can be costly. The financial markets have worked hard to reduce these errors. In the floor-trading model, a majority of trade operations were conducted manually. The trades were recorded on paper or trade cards and manually entered by an army of clerks. Things are bound to get lost in translation, and they often were. Traders misspoke or misheard or miswrote information on the order or trading card. Clerks mistyped. Every morning traders would review the “out-trades,” trades that could not be matched. Let's say that there were two traders who traded 500 lots of IBM. They recorded this information on a paper or trade card, which was then entered by a clerk for matching. There are a number of ways a matching error could occur. The two traders might not have recorded the information correctly. The clerk could enter incorrect trade information that did not match what the traders entered. These trades were reviewed by traders the next day, and disputes were usually settled among traders and their firms.

For example, the CME used to have over 25% of its trades recorded as out-trades. As the financial markets adopted technology, it began reducing its dependency on error-prone humans for most components of the trade cycle. So it would only be logical to think that the era of out-trades would be over in electronic trading, now that trading is conducted through computer screens and every trade is transmitted electronically. There are no manual entries and no middlemen. The trade information is always recorded properly, and there is an audit trail for every trade, as discussed in a previous chapter. And though it is true that electronic trading certainly helped to reduce out-trades caused by human errors, new issues such as technology glitches still cause trade execution that at times must be canceled by the exchanges. The world of electronic trading might have gotten rid of trade cards and the crowded floors, but it has not entirely eliminated trading errors. Trading still relies on humans. Whether it is a trader entering trades on a computer screen or creating rules for automated trading systems, humans are still the key element in the trade cycle, and thus the trading errors continue.

In the world of electronic trading, speed rules trading, so when errors occur they are significant and extremely costly for the financial markets. The past 20 years of electronic trading are filled with examples of trading errors that have jolted traders and the markets time and time again. To cope with these trading errors, exchanges around the world have policies to handle erroneous trades. Out-trades are replaced by terms such as busted trades, which are erroneous orders that are canceled by the exchange. The reasons for errors in electronic trading can be in two main areas: system glitches and “fat-finger mistakes.” The system glitches can occur in any of the components in the trade cycle. Fat-finger mistakes are simple human errors that occur when a trader unintentionally enters the wrong trade information. In that sense, fat-finger errors are similar to the old out-trades from the floor-based systems.

In the floor-trading days, out-trades were generally handled and resolved by the brokers and trading firms. Any losses or adjustments were simply handled outside the exchanges. In electronic trading, things are different. Every trade is recorded as it occurs and can't simply be erased by the trading parties, thus requiring the exchange to determine when to bust a trade. Every erroneous trade is costly, but some costs are confined to a particular trading firm, whereas others can have widespread impact on the market.

“Fat Fingers”: A $331 Million Mistake30

On December 13, 2005, a simple human error led to an instant $331 million loss for Mizuho Securities Company. A trader at Mizuho was preparing to sell one share of J-Com at a price of 610,000 yen. The actual order submitted was 610,000 shares of J-Com at 1 Yen! News of the bargain price traveled fast, and buyers quickly bought shares of J-Com. It was an early Christmas present for day traders, who were the most active buyers, but they were not alone. By the end of the trading day, Morgan Stanley, a large investment bank, owned 31.5% of J-Com. Although the trades were not busted, there was substantial criticism of the exchange for failing to stop the trade even after the trader realized his mistake and tried to cancel the trade. A simple human error led to frenzied trading on the Tokyo market, contributing to an almost 300-point drop on the Japanese index, the Nikkei 225, which closed down 2%. 31 In the end, six of the trading firms agreed to repay $141 million. Mizuho is expecting to recoup the remaining amount from the exchange due to the lack of controls on the exchange to stop erroneous trades.

Similarly, one of the traders at the former Lehman Brothers erased almost $50 billion (30 billion pounds) off the FTSE index in 2001 when he accidentally submitted £300 million for a trade instead of £3 million. The erroneous trade caused the FTSE 100 to drop almost 120 points. Another fat-finger mistake caused an almost 100-point drop in the Dow Jones Industrial Average when a trader at Bear Stearns entered a $4 billion sell order instead of $4 million. 32 These mistakes, although caused by a single firm, have widespread impact on the markets and require exchanges to deal with these trades and the potential losses and adjustments, which at times can take weeks.

The fat-finger mistakes are still likely to occur in the electronic trading world. The trading firms and exchanges continue to implement controls to catch orders that might be caused by a fat-finger mistake. For example, CME has price banding limitations, which restricts its trading platform from accepting orders outside a specified trading range for products. The front-end trading systems have a number of checks built in to control a potential incorrect order from flowing to the exchanges. These applications can set controls to limit the size and price of orders submitted by traders. For example, if a trader sets a limit for order size at 1000, an alert would pop up on his screen to confirm a trade larger than 1000. Although these controls are likely to reduce the number of fat-finger mistakes, they are still likely to occur.

Some of the Memorable Fat-Finger Mistakes Around the World33

UBS's £80 Order (January 1999)

A careless trader entered a sell order for 10 million shares on the Swiss exchange for a Swiss pharmaceutical company, Roche. The total number of shares issued for the company was 7 million shares. The order remained in the order book for over two minutes until the trader realized his mistake and entered a buy order to execute against his sell order.

Blame the Keyboard (October 1998)

A trader, leaning his elbow on his keyboard, triggered a 14,500 contract sell order for a 10-year French government bond on MATIF; 10,000 contracts were executed. The keyboard for electronic trading applications is designed with some “hotkeys” for fast execution. In this case, the F12 key was programmed for “instant sell,” meaning that if a trader enters a quantity and presses F12, an instant market order is submitted to the exchange. The firm suffered several million dollars in losses.

LSE's Biggest Order (February 2001)

An erroneous order for a U.K. software company, Autonomy, was entered by a trading firm for £8.1 billion, over four times the total capital of the firm. The order was canceled almost immediately by the exchange when it noticed the anomaly.

Mixing the Order Size with Company Code (September 1997)

LSE received three orders within an hour for 989,529 shares of Zeneca. Each order, valued at £21 million, was three times the normal volume for that day. When the exchange called the firm to inquire about the order, the firm realized that the trader entered Zeneca's Sedol number, the code used by the exchange to identify the stock, as the order size. If the order had been executed, it would have cost the firm £60 million.

£300 Million Instead of £3 Million (May 2001)

A trader at Lehman Brothers caused a 120-point drop in the FTSE 100 and wiped out £30 billion of value from the index when he sold shares of BP and AstraZeneca. He keyed in £300 million instead of £3 million. The firm was fined £20,000.

2000 Instead of 2 Shares (January 2006)

A Citigroup trader intended to purchase two shares of Nippon Paper at ¥502,000. The trader accidentally entered a buy order of 2000 shares instead. Furthermore, the firm's compliance department approved the trade, thinking the shares were worth ¥500 instead of ¥502,000. The firm's CEO, Charles Prince, flew to Japan to apologize for the mistake.

$4 Billion vs. $4 Million (October 2002)

The Dow Jones Industrial Average fell 100 points when a trader at Bear Stearns entered a sell order for $4 billion instead of the intended $4 million. More than $600 million of the stock exchanged hands before the mistake was identified. The mistake was blamed for much of the 183-point drop in the market.

Rugby Executing $50 Million Trade (September 2006)

At Bank of America, a trader's keyboard was set up to execute trades by simply pressing the Enter key whenever the senior trader gave the go-ahead. The trader missed a rugby ball thrown his way, which landed on the keyboard and trigged a $50 million trade ahead of schedule. The ball thrower was reprimanded, but no additional actions were taken. As one of the traders put it lightly: “Rugby balls are a regular danger on any trading floor, so the victim trader ought to have hedged against this possibility.”

Oh, the Zeros on the ¥ Again (December 2001)

A UBS trader intending to sell 16 shares of Dentsu at ¥600,000 instead sold 610,000 at ¥6. This was hours before UBS was getting ready to take Dentsu public in the year's biggest IPO. By the time the mistake was discovered, 64,915 shares, almost half of the 135,000 in the Tokyo listing, were already sold. Dentsu's bid was set at ¥600,000 for the open, but fell to ¥405,000. UBS lost over $100 million when it was forced to buy the shares it sold.

The electronic trading system is credited with bringing competition, faster order execution, transparency, and anonymity to the financial markets. The exchanges as well as the financial community have reaped the rewards of the new model. Though electronic trading is transforming the financial industry, there still remain some challenges that must be recognized and, hopefully, overcome. The most significant issue is the inevitable unreliability of computer technology. Both the hardware and software are prone to failure. In particular, the software is terribly complicated and difficult to verify as correct. As the financial community gains more experience with electronic trading systems, it will learn to build more reliable systems that can mask and work around these failures. Since exchanges are using the modular exchange model, every component by every vendor must be built with the same devotion to quality for the entire system to remain bug free. The exchange is only as good as the weakest component in the trade cycle.

As long as humans are involved in any process, there will be human error. These errors can range from simple mistakes to rogue trading—activity by a trader who gets around limitations to put a firm at grave risk. Again, these mistakes can be mitigated by having better error detection on anything that requires manual interaction. It could be as simple as raising a warning whenever a trader inputs a trade beyond some value or banning flying objects in a trading room. When mistakes are made, exchanges will need to develop better resolution procedures than ad hoc decisions to cancel trades. A more difficult issue is dealing with panic. Electronic trading brings markets closer to the economic ideal of “perfect information,” but when the information is imperfect, traders panic and markets swing wildly. In a fast-moving market, it will be near impossible to tame fear and greed. Despite these issues, electronic trading solves far more problems than it creates.

Endnotes

1. Moore, James, “Euronext Hit by System Faults,”; www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/2852140/Euronext-hit-by-system-faults.html; (May 17, 2003).

2. “London Exchange Paralyzed by Glitch Blow to a Market Facing New Rivals; Huge Trading Day,”; http://online.wsj.com/article/SB122088611707510173.html?mod=hpp_us_pageone; (Sept. 9, 2008).

3.

4. “History of New York Stock Exchange Holidays,”; www.nyse.com/pdfs/closings.pdf; (Nov. 2008).

5. “Software Bug Caused Tuesday's TSE Outage,”; www.thetradenews.com/trading/exchange-traded-derivatives/2136; (July 23, 2008).

6. “LIFFE Suffers Sixth Connect System Outage This Year,”; http://64.233.169.132/search?q=cache:SxcjWqKJfhEJ:findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_hb5555/is_/ai_n21937801+liffe+system+outage&hl=en&ct=clnk&cd=1&gl=us; (Sept. 2001).

7. Moore, James, “System Fault Forces LIFFE to Shut Down,”; http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qn4158/is_/ai_n19199066; (July 5, 2007).

8.

9.

10. Moore, James, “System Fault Forces Liffe to Shut Down,”; www.independent.co.uk/news/business/news/system-fault-forces-liffe-to-shut-down-451780.html(June 5, 2007) .

11. Waller, Martin, “London Stock Exchange Glitch Costs millions,”; http://business.timesonline.co.uk/tol/business/markets/article4710793.ece; (Sept. 9, 2008).

12. Shah, Neil, “London Exchange Paralyzed by Glitch Blow to a Market Facing New Rivals; Huge Trading Day,”; http://online.wsj.com/article/SB122088611707510173.html?mod=hpp_us_pageone; (Sept. 9, 2008).

13. Wearden, Graeme, and Tryhorn, Chris. “Seven-Hour Outage Creates City Chaos,”; www.guardian.co.uk/business/2008/sep/08/freddiemacandfanniemae.creditcrunch; (Sept. 8, 2008).

14. Sakoui, Anousha, “Trading Halted on London Stock Exchange,”; http://us.ft.com/ftgateway/superpage.ft?news_id=fto090820080742439122&page=2; (Sept. 8, 2008).

15. “Electronic Trading at CBOE Interrupted,”; http://money.cnn.com/news/newsfeeds/articles/newstex/AFX-0013-11945248.htm; (Nov. 10, 2006).

16.

17.

18.

19. Baer, Justin, “United shares plunge on old news story,”; www.ft.com/cms/s/0/b843a240-7ddd-11dd-bdbd-000077b07658.html?nclick_check=1; (Sept. 8, 2008).

20. Brown, Jeffery, “United Airlines Tallies Damage from False Stock Report,”; www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/media/july-dec08/unitedstock_09-09.html.

21. Helft, Miguel, “How a Series of Mistakes Hurt Shares of United,”; www.nytimes.com/2008/09/15/technology/15google.html; (Sept. 14, 2008).

22. Regan, Keith, “Computer Glitches Heaped Fuel on Stock Sell-Off,”; www.ecommercetimes.com/story/56032.html?wlc=1222521986&wlc=1222648420; (March 1, 2007).

23. Salisbury, Ian, and Rogow, Geoffery. “Glitches Cancel Electronic Trades,” Wall Street Journal; www.marketwatch.com/news/story/glitches-cancel-electronic-trades/story.aspx?guid=%7B76F833E8-6A8E-4C57-9865-7B418F9DCFC7%7D; (Sept. 24, 2008).

24. Goldman, David, “SEC Bans Short-selling. Agency puts temporary halt to trading practice that ‘threatens investors and capital markets’ for 799 financial companies,”; http://money.cnn.com/2008/09/19/news/economy/sec_short_selling/?postversion=2008091907; (Sept. 19, 2008).

25.

26.

27.

28. “Erroneous Orders Routed to NASDAQ Result in Cancelled Trades,”; www.nasdaq.com/newsroom/news/newsroomnewsStory.aspx?textpath=pr2008ACQPMZ200809301844PRIMZONEFULLFEED151328.htm&cdtime=09%2f30%2f2008%20+6%3a44PM&title=Erroneous%20Orders%20Routed%20to%20NASDAQ%20Result%20in%20Cancelled%20Trades; (New York, Sep. 30, 2008).

29. Rooney, Ben, “Google Price Corrected After Trading Snafu. Closing price adjusted after shares of the tech giant plummet due to erroneous trade. Change to final Nasdaq value to follow,”; http://money.cnn.com/2008/09/30/news/companies/google_nasdaq/index.htm; (Sept. 30, 2008).

30. Wallace, Bruce, “Trading Blunder Raises Concerns about the Tokyo Stock Exchange,”; http://articles.latimes.com/2005/dec/14/business/fi-nikkei14; (Dec. 14, 2005).

31. McCurry, Justin, “Too Fat, Too Fast. The £1.6bn Finger,”; www.guardian.co.uk/business/2005/dec/09/japan.internationalnews; (Dec. 9, 2005).

32. McCurry, Justin, “Too Fat, Too Fast. The £1.6bn Finger,”; www.guardian.co.uk/business/2005/dec/09/japan.internationalnews; (Dec. 9, 2005).

33. Wilkinson, Tara Loader. “The fat finger points to trouble for traders,”; www.efinancialnews.com/usedition/index/content/2447370453(Mar. 14, 2007) .

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.