6. From National to Global Competition

Executive Summary

There was a time when there were 250 stock exchanges in the United States and not too long ago when there were 23 in India. Competition in those days was, at best, local. Improved communications and falling communications costs brought competition to the national level, and the number of stock exchanges fell dramatically in most multi-exchange countries. Recently, with the shift to screens and the need to build volume to lower per-trade costs, exchanges have begun competing on a global level. This competition has been most successful when the attacker is electronic and the target still floor based—a diminishing opportunity.

Before we explore the shift from national to global competition, we must first clarify what we mean by competition among exchanges. Exchanges, like most business organizations, want to grow. Stockholder-owned exchanges want to grow to increase profits, to benefit their stockholders. Even older member-owned exchanges want to grow to offer increased trading and order-filling opportunities to their members. In both cases the objective is to benefit the owners of the exchange, who traditionally were members and increasingly today are stockholders.

This growth can either be competitive growth or noncompetitive growth. Competitive growth occurs at the expense of other exchanges; noncompetitive growth occurs without any impact on other exchanges. What we are concerned about in this chapter is competitive growth—growth that occurs to the detriment of another exchange and often growth that results from a deliberate attack on a product of another exchange. We are not concerned here about noncompetitive growth, such as where an exchange starts a new product for which there is no close substitute at any existing exchanges within the same political or geographical realm. In other words, noncompetitive growth refers to growth at an exchange that results from the development of new business, not from attracting customers away from other exchanges. For example, in the past, when there were significant barriers to sending trades into Brazil, the rapid growth of the BM&F could be viewed as noncompetitive growth because it occurred without any negative impact on the growth of other exchanges in the world. So it is not necessarily the case that one exchange's increase in total market share occurs at the expense of any other exchange, since this increase in market share could arise from new business that would not have gone anywhere else.

But our focus here is on competitive growth, or more accurately, on competition between two or more exchanges in which each exchange is attempting to grow and will do so, at least partially at the expense of competing exchanges. There are actually two types of competition, one obvious and the other more subtle. They are:

• Direct competition, where two (or more) exchanges compete for the same product:

• An exchange lists a product that is already established on another exchange.

• Two (or more) exchanges list the same new product at roughly the same time.

• Indirect competition, where two exchanges with non-identical products compete for the same speculative capital

This requires some elaboration. A case where an exchange lists a product that has already been listed and has developed a significant amount of liquidity on another exchange is a clear case of direct competition. Generally the newly listing exchange will succeed only if it is able to draw market share away from the product that already exists at the other exchange. And as has been mentioned elsewhere in this book, the principle of liquidity-driven monopoly generally guarantees that all the liquidity, all the trading, will be eventually resident on only one of the two competing exchanges. Because of this principle that recognizes that traders are attracted by liquidity and will not generally leave a liquid market with lots of buyers and sellers to trade at a new illiquid market with few buyers and sellers, most such attacks on the liquidity of existing products result in failure. The only exceptions are when the attacking exchange has some very significant advantage, and the only cases in which we have seen attacks on liquid markets succeed have been cases of electronic exchanges attacking floor-based exchanges. Examples of failures of such attacks on entrenched products include the case where the CME and the CBOT in the 1980s attempted to draw liquidity away from NYMEX energy products by listing their own energy products. The attempt failed miserably.

Another example is where a number of brokerage firms came to the CME and asked it to list a gold contract in the mid-1980s, after the then dominant COMEX was unable to efficiently process the paperwork during periods of significant gold trading. The CME had already lost an earlier competition over gold with the COMEX, and its contract had been dormant for a couple of years. Based on the requests from the firms and the belief that its systems would do a better job than COMEX in keeping up with the avalanche of paper from a hyperactive market, it resurrected its gold contract. In 1987 it traded 261,000 contracts, a solid first-year number but representing only 2% of the two exchanges’ combined volume. COMEX was able to clean up its act and beat back the CME, whose gold volume fell back to zero before the end of the next year. So, like most other cases, the liquidity-driven monopoly prevailed and the CME's attack was a failure.

On the other hand, the most famous example of a successful attack on entrenched liquidity came when the all-electronic DTB exchange (later to merge with Swiss-based SOFFEX and be renamed Eurex) successfully stole the German government bond futures from the floor-based LIFFE in 1998. This, as we mentioned, was a case where the attacking exchange had a substantial advantage; specifically it was fully electronic, whereas LIFFE was still stuck in the world of trading pits. This also was an early case of global competition in that it was a German-Swiss exchange attacking a British exchange.

A second type of direct competition whereby two or more exchanges list the same or closely related products at roughly the same time is also a clear case of direct competition; typically one exchange is the winner, and given the liquidity-driven monopoly effect, the winner takes all. Back in 1981, the CME, the CBOT, and NYFE1 (the New York Futures Exchange) all listed negotiable certificate of deposit (CD) futures at roughly the same time (see Figure 6.1). For a few months volumes grew at all exchanges, but within a relatively short period of time, the CME surged ahead, and before the end of 1982, volumes at the other two exchanges had shrunk to zero. This was because the CME already had a liquid short-term interest rate contract, the three-month Treasury bill contract, which allowed spread trades with the newly listed three-month CD contract, a quick way to build liquidity. So the CME won the three-way competition. Usually, winning a competition assured the victor of a contract that would continue for some time.

In this case, however, there were two events that conspired to cut short the life of the CD contract. 2 First, the CME started a new short-term interest rate contract based on U.S. dollar deposits offshore, called three-month Eurodollars. The contract's value moved with the average LIBOR rate based on a survey of London banks. This was to eventually become the biggest futures contract in the world. The second event was a delivery problem that scared traders away from CD futures. There was a list of banks whose CDs were deliverable on the contract. One of these banks was Continental Illinois National Bank, which had made a number of oil and gas and developing-country loans that started looking very risky. In 1982, analysts began downgrading Continental's earnings estimates, and the rating agencies began downgrading its debt. 3 Even before the bank actually went into bankruptcy, buyers of CD futures began to fear getting a delivery of Continental CDs and started shifting their positions to the Eurodollar futures contract. The result was that all the liquidity in the CD contract eventually moved to the Eurodollar contract, which became the benchmark for short-term, U.S. dollar interest rates. The CD contract had a short, sweet life and was dead within five years.

Another example of two exchanges listing the same product at roughly the same time occurred when the CME and CBOT both listed OTC stock indexes in the mid-1980s. The CBOT listed the Nasdaq 100, and the CME listed the S&P OTC index because it had a relationship with the S&P Corporation. Both exchanges saw some volume, both in 1985 and 1986, and the CBOT's Nasdaq 100 contract did about 50% more volume, but by 1987 both contracts were dead. This was a case of a product whose time had not yet come; despite spending about $1 million each on marketing their products, both exchanges failed to establish a successful contract. Ironically, the CME obtained listing rights from Nasdaq and successfully relisted the Nasdaq 100 a decade later, in 1996.

Measuring Volume at Futures Markets

Comparing futures contracts and exchanges to one another is a tricky thing because the measurement of trading activity differs by country and the method used can give very different results. There are essentially two ways to measure the volume of trading at a futures exchange; the method chosen depends on the way exchanges and brokerage firms in a country charge fees. In places like the United States, Canada, and Europe, fees are based on the number of contracts traded, so exchange volumes are reported as the number of contracts that change hands during a specific period of time, typically a day, a month, or a year. In countries like China and India, on the other hand, fees are based on the nominal value of a trade, so in those countries, volume is measured by the nominal value of the contracts traded.

Using the American-European method, a Eurodollar contract and a cattle contract both count as one contract. Using the Chinese-Indian method, a Eurodollar contract would count for 25 times that of a cattle contract because a Eurodollar contract has a nominal value 25 times that of a cattle contract—$1 million for each Eurodollar contract vs. about $40,000 for one cattle contract (assuming cattle were selling for $1 per pound for the 40,000-pound contract).

So, if 100,000 Eurodollar contracts were traded and 50,000 live cattle contracts were traded on a given day, together that would be a volume of 150,000 contracts using the American-European method, or $100,002,000,000 using the Indian-Chinese method. It's not that one method is superior; each has its own logic driven by local fee customs. One could debate the issue of which fee custom makes the most sense, but we will not do that here. But because the Washington, DC-based Futures Industry Association (FIA) publishes American-style volume numbers for all exchanges that report to them, and because most exchanges want to be included in these monthly reports, increasingly those exchanges that report locally on a nominal value basis also report the number of contracts traded to the FIA.

Indirect competition is a bit more subtle. Usually when we think of competition we think of the case where two or more exchanges are listing the same or very similar contracts. The logic here is that participants in the industry in which the underlying asset is traded can logically go to either one of the competing exchanges to manage the risk associated with the underlying asset. However, there is another side of this equation, and that is not only do these markets attract individuals and firms involved in the production, processing, or merchandising of the underlying asset or commodity, they also attract speculative capital. And speculative capital can go anywhere but is most interested in markets that are liquid and have sufficient volatility to offer trading opportunities. So a hedge fund or managed futures fund can trade cattle, corn, or a stock index as long as the market is liquid and the fund can build a successful trading strategy for that market. In this sense the corn contract at one exchange is competing with the cattle contract at a second exchange and a stock index contract at a third exchange. So, as long as the same hedge funds, swap dealers, managed futures funds, investment banks, and individuals have access to a group of different exchanges, all those exchanges and their products are competing for the same speculative capital.

Bragging Rights Competition

Exchanges tend to compete for bragging rights. So, at one level, exchanges are competing to be able to say that they are the biggest, the most rapidly growing, or the exchange with the largest product in some specific asset class. This was more important in the days before exchanges became for-profit, stockholder entities, focused on the bottom line. Exchanges were still owned by their members. Then, being the biggest, or at least moving toward the top of the heap, was the goal of many exchanges. It was little different from the competition among sports teams from different cities or universities. For example, for decades the Chicago Mercantile Exchange and the Chicago Board of Trade engaged in a sort of schoolboy rivalry as to which exchange was the biggest. Size among exchanges generally refers to the level of trading volume that occurs at those exchanges. But when the CME was still the number-two exchange in terms of trading volume in 1993, it opened a new trading floor that had more square feet than the CBOT, and it immediately created commemorative T-shirts and hats that read “NOW THE WORLD'S LARGEST EXCHANGE.” Of course, a short time later the CBOT opened a new, larger trading floor and regained the square footage crown. Not to be outdone, the CME began reworking the definition of “trading volume” and decided to begin using a measure that included options exercises and other things that made the CME look larger than it was under the conventional definition. The Futures Industry Association, the entity that publishes exchange volume, balked at the unilateral definitional change; no other exchange adopted the CME approach, and the CME eventually backed down. Schoolboy bragging doesn't disappear but becomes much less important as exchanges move from the member-ownership to the stockholder-ownership model, where everyone has their eyes on profits and stock prices.

Securities vs. Derivatives Exchanges: Fees and Revenues

All exchanges compete by making products available for trading and attracting traders to trade those products at their exchanges. But there is a difference between the securities and derivatives exchanges’ approaches to this competitive activity. First, a securities exchange's products are mainly stocks of companies that have agreed to list on them. So, product development involves seeking these company listings. The exchanges may also allow trading in companies that have listed elsewhere, or developed equity- or bond-based products such as exchange-traded funds (ETFs) or exchange-traded notes (ETNs) to offer investors tailored exposures not efficiently obtainable from individual equities or bonds.

Securities exchanges receive listing fees from public companies that list with them. 4 They do not receive listing fees from companies in which they allow trading but do not formally list. They also do not receive listing fees for products they create that are based on indexes published by others. On the contrary, the exchanges must pay for the rights to use these indexes. AMEX, now part of NYSE Euronext, for example, must pay fees to Standard and Poor's for the very popular ETF, Spider (SPDR), listed there.

Derivatives exchanges never receive fees from anyone for listing products, and, like stock exchanges, they sometimes even pay fees for the privilege of listing a product that utilizes the intellectual property of another company, such as the indexes of Standard and Poor's, Dow Jones, Wilshire, or Russell. At the risk of overgeneralizing, derivatives exchanges compete by creating new products and winning customers for these new products, whereas securities exchanges (within a single country) compete by listing the same products and enticing customers to their markets via a combination of strategies, including liquidity enhancement and actually paying for order flow. There is a difference here between stock exchanges and derivatives exchanges.

Local to Regional Competition

There was a time when competition among exchanges was local and regional. And, as regional victors became established, countries were peppered with a number of regional stock exchanges. The United States still has stock exchanges over 100 years old in New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago, and Los Angeles, but there were once a great deal more. The Chicago Stock Exchange, for example, was the result of a merger of exchanges based in St. Louis, Cleveland, Minneapolis-St. Paul, and New Orleans. In fact, during the 19th century there were roughly 250 stock exchanges operating in the United States. 5

As late as the 1990s, India had 22 regional exchanges in addition to the main exchange in the financial center of Bombay. England once had 20 stock exchanges and today has only the LSE and a few small competitors. In all these cases you needed regional exchanges to trade regional stocks because it was too costly, difficult, and slow to communicate and deliver stock certificates, even across a country as small as England.

But as communication became cheaper and faster, regional exchanges began trading national products. The regional stock exchanges in the United States have almost totally abandoned any notion of regional stocks. All stocks are now national. And all the regional exchanges compete for trades in the same stocks. The same is true in India. The 23 regional exchanges began competing in the same stocks and were eventually unable to match the financial might of Mumbai (known until recently as Bombay, when a nationalistic Hindu party began throwing out the old British names and restoring the original Hindu names of many cities). Therefore, business tended to migrate to the financial center and the regional exchanges either got absorbed, converted themselves into brokerage firms, or simply dried up and blew away. So, all that's left in England is the London Stock Exchange and a handful of niche players. Most of the Indian regionals—New Delhi, Kolkata, Chennai, and so on—no longer see any real trading. And in the United States, a system mandated by the SEC that connects all regional U.S. exchanges to the New York Stock Exchange has saved them by ensuring that as long as they offer competitive prices they will continue to get a piece of the action. However, over the past few years the number of independent regional exchanges has fallen from five to two (the Boston Stock Exchange and the Chicago Stock Exchange), with the others (Philadelphia, Pacific, and Cincinnati) being absorbed into Nasdaq, the NYSE, and the CBOE, respectively.

Competition and Clearing

The relationship that an exchange has with its clearinghouse is a very important factor when we look at an exchange's ability to compete. There are really three possible relationships between an exchange and a clearinghouse:

• The clearinghouse can be internal to the exchange.

• The clearinghouse can be an external, independent entity or at the extreme.

• The clearinghouse can be an external, independent entity that commonly clears multiple exchanges that have identical, fungible contracts, allowing a position to be put on at one exchange and offset at another.

From the point of view of the exchange, particularly an exchange that is an aggressive innovator or “first mover,” one that tends to be the first to market with new products, the internal clearinghouse is the best, and this is the model that futures exchanges have generally chosen for themselves. Since the internal clearinghouse is totally controlled by the exchange, its priorities can be changed quickly to deal with a shifting competitive environment. For example, if the exchange has a new product that it needs to launch very quickly, it can tell the clearinghouse to devote all necessary resources to prepare for this new contract and put other projects on the back burner. This is difficult to do with an external clearinghouse. There, the exchange's new product must take its proper place in the queue behind other products from other exchanges and wait its turn.

Though there are efficiency advantages to having several exchanges clear their products on a single common clearing system, competitive problems can sometimes arise. One of the best examples of problems with an external clearinghouse was that of the Board of Trade Clearing Corporation (BOTCC) and the exchange that created BOTCC, the CBOT. In 2003, the then largest futures exchange in the world, Eurex, decided to create a Chicago subsidiary to compete directly with the cornerstone products listed at the CBOT. At that time, BOTCC was and had been the entity that cleared all CBOT trades for the past 70 years. But because the BOTCC was an external, independent clearing entity, when Eurex approached BOTCC to clear its Treasury products and offered an attractive deal for doing so, BOTCC jumped at the chance. One of the motivations for BOTCC to agree to clear the products of its long-time partner's major competitor was that BOTCC feared that Eurex would be successful and the revenues from its then major client, the CBOT, would disappear. So, it took a calculated risk and decided to clear the products of the Eurex Chicago subsidiary.

Quite naturally, the CBOT decided to sever its relationship with BOTCC, and it asked the CME to take over the clearing of CBOT contracts. The CME agreed to do this because none of the CBOT products were competitive with its own products and it represented the chance that this could lead to a closer relationship between the two exchanges as they did battle against the rest of the world. In fact, as is mentioned elsewhere in this book, the two exchanges grew close enough that they actually merged in the summer of 2007.

The third model of several exchanges commonly clearing identical, fungible contracts is both the best and the worst of all models. It is difficult to imagine a group of competitive exchanges choosing this model, and thus it would most likely exist when imposed by a regulatory entity, as it was when the SEC mandated it for the securities options industry in the United States.

Back in 1973, the CBOE was founded by the CBOT to allow trading of options on individual shares of stocks, and this involved the creation of a captive clearinghouse. The CBOE was successful, and naturally a number of the existing equity exchanges decided that they too would like to list options, a logical product extension for them. The SEC, which regulates all U.S. securities, including options on securities, required that the CBOE spin off its internal clearinghouse and make it available to all other options exchanges in the United States. So, in 1975 the CBOE clearinghouse was spun off and renamed the Options Clearing Corporation (OCC). The SEC further required fungibility of products so that not only would the now independent clearinghouse clear the products of all options exchanges, it also would allow an option that was listed on more than one exchange to be purchased on one exchange and then be sold on the other options exchange cleared by the OCC. This allowed positions to be put on at any U.S. options exchange and offset at the same or any other U.S. options exchange. What this meant was that if one exchange had a successful product, and another exchange decided that it wanted to list that same product, traders knew that if they took a position at the new relatively illiquid exchange, they could always offset the position at the more liquid exchange, if they needed to do so. This basically gave a helping hand to any exchanges that wanted to compete with a product that was already successfully listed at an exchange. The SEC felt that this would create price competition among the various options exchanges and keep transaction fees low. From this point of view, it actually was the best of the models because it encouraged vigorous price competition. However, from the point of view of an individual exchange, especially an exchange that had worked hard to develop liquidity in some new product, this was the worst of all systems because it gave the least protection to the new product.

This third model has been exclusively applied to securities options in the United States. However, there have been proposals to also apply this model to U.S. futures. The brokerage firms, which are always concerned about the fees being charged to them by the exchanges, lobbied in 2003 through their trade association, the Futures Industry Association (FIA), for the CFTC or Congress to impose an SEC-type model on the futures industry. The closest that futures markets came to “real interexchange competition,” said John Damgard, FIA president, was the “single stock futures exchanges where U.S. law has mandated fungible contracts [and a single clearing entity].”6 Damgard was referring to the new futures on individual stocks, which Congress insisted be regulated jointly by the SEC and CFTC and follow the fungible contract model of single stock options. Damgard went on to say that if Congress continues to pay attention to consumer and user concerns, then fungibility would spread to traditional futures as well.

Of course, the futures exchanges have argued that futures contracts are the intellectual property of exchanges and they should be able to protect and not be forced to share this property with every latecomer who stumbles into the party. In addition, they argue, forced fungibility would actually harm the users because the new competition would fragment liquidity into several smaller pools, each with a bid/ask spread that would be wider than the ones in the existing monopolistic pools. So, even if competition did drive down exchange fees, this savings could be more than offset by the cost of wider bid/ask spreads. 7

While the debate raged between the brokerage firms and users, who wanted product fungibility and common clearing, and the exchanges, who felt these were an invention of the Devil, the federal futures regulator stayed neutral. CFTC Chairman James Newsome made it clear that he wanted the industry members to work it out among themselves; he even had his staff facilitate meetings between the exchanges and FIA members. He also held a formal roundtable discussion on the issue.

Government neutrality was pushed aside when the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) dropped a bombshell. In late 2007, the DOJ requested comments from other agencies regarding a possible revamping of financial regulations in the United States. The DOJ responded by arguing in a January 31, 2008, 22-page letter that product fungibility and common clearing should be imposed on the futures exchanges. The DOJ maintained that because futures exchanges in the United States have captive clearing organizations, competitors are not able to tap into the existing liquidity at the exchange that first listed the product. The letter noted that futures exchanges, when they compete for new products, find themselves in a winner-take-all situation. The network liquidity effects, 8 which is to say the fact that buyers and sellers all want to be in the market with the greatest liquidity, result in buyers and sellers congregating eventually at a single exchange when two exchanges compete. And the DOJ maintains that if the futures industry followed the model of the securities industry, specifically the equity market and the equity options market, this would significantly enhance competition among the exchanges, resulting in lower costs of doing business and greater innovation.

It was interesting to note that this DOJ comment letter had such a chilling effect on the industry—and specifically on the CME, which was in the process of trying to acquire NYMEX—that the stock price of both the CME and NYMEX dropped like a rock. 9 The DOJ had gone along with the CME's first big merger with the CBOT in the summer of 2007, but the question now was, would it go along with the proposed CME merger with NYMEX and would it require a restructuring of the industry as the price the CME had to pay for the approval?

Competition in Options

In the beginning there was only the Chicago Board Options Exchange (CBOE). The CBOE, which was conceived by a group of traders at the CBOT, was the first exchange in the world to list options on equities. It was an idea whose time had come. In fact, a number of stock exchanges around the country (like the AMEX, the Philadelphia Stock Exchange, and the Pacific Exchange) saw the CBOE's initial success and felt that the idea was sufficiently powerful that they also began to list options on individual stocks. Initially, the exchanges did not compete directly over identical products, and in a manner similar to basketball or football drafts, the options exchanges would take turns picking stocks on which they would list options. One exchange would choose first, then another exchange, then a third exchange, and so on. Unlike the basketball and football drafts, which are held annually, the options sessions were done a number of times each year. While this was convenient for the exchanges to each have monopolies on the various stock options, the SEC actually wanted it this way. The problem was that had there been multiple listings of each option, for example, both CBOE and AMEX listing IBM, there was not a practical way to ensure that a customer wanting to buy a specific IBM call would have his order filled at the exchange offering the best price. Communication systems were simply not good and fast enough to have exchanges communicate with each other on every order for every one of the many strikes and expirations being offered. The bandwidth of the 1970s was simply not sufficient. So it was best, the SEC thought, to have each company option at a single exchange.

Though the SEC formally eliminated the practice of listing new options only on a single exchange in 1990, each options exchange still chose not to list those options in which significant liquidity had been established at another exchange.

Enter the ISE

Back in 1996, William Porter, who had already founded the online brokerage firm called E*TRADE, and Marty Averbuch wanted to figure out a way to reduce the relatively high transactions costs associated with options so that E*TRADE customers could affordably begin trading these options. 10 They believed that this monopolistic structure in the options market, where each exchange had its own set of options that the other exchanges respected and would not list themselves, was a significant obstacle to lowering options trading costs. Porter realized that the only way to reduce the costs of trading would be to create a new registered options exchange, and he enlisted the support of a consortium of broker-dealers who were also interested in reducing the cost of trading options.

The first thing they did was to hire a small research group called K-Squared Research, founded by David Krell and Gary Katz, both of whom had been managers of the options division of the New York Stock Exchange. The initial task was to produce a feasibility study on the creation of a new options exchange. Krell and Katz came back with the recommendation that a new all-electronic options exchange be created.

The consortium decided to move forward with the new exchange, and the International Securities Exchange (ISE) was founded in September 1997, with Porter as chairman and Krell as CEO. The decision was made to use the technology supplied by OM, the Swedish exchange that had supplied a matching engine to exchanges around the world.

Still, a year and a half away from actual product launch, the ISE announced in November 1998 that it intended to list the 600 highest-volume options trading at other exchanges. The impending launch of the ISE had already created some anxiety for the existing options exchanges, but the explicit announcement that it intended to directly compete with the highest-volume contracts at all the existing exchanges destroyed the comfortable era of noncompetition, and within nine months there was an all-out listing war in the options markets. Both CBOE and AMEX listed Dell options that until then had been a monopoly product of the Philadelphia Stock Exchange. Philadelphia, in turn, listed Apple, a monopoly product of AMEX, and IBM, Coca-Cola, and Johnson & Johnson, all monopoly products of the CBOE. By the end of 2001, virtually every important product had multiple listings at several exchanges.

When the ISE actually went live on May 26, 2000, it started with a very modest listing of options on only three stocks. Once it was clear that the system worked well, it began adding 25 new names every month. By the end of 2001 the ISE had listed options on 458 of the most actively traded options contracts in the United States. Though there was an increase in trading overall, there was no question that the ISE was taking volume away from the existing exchanges, especially the CBOE. Between 2000 and 2001, the CBOEs net income fell 35%, from $10.9 million to $7.1 million. 11

So, what is the state of the options industry today? The first dimension to grasp is the dramatic growth in trading activity. In the United States, all stock options and stock index options trades are cleared in a single place, the Options Clearing Corporation. 12 Between 2005 and 2007, the number of options contracts cleared at the OCC essentially doubled, from 1.5 billion to 2.9 billion. 13 At the same time, the OCC dropped its clearing fees by 50%, from 3.4 cents per contract in 2005 down to 1.7 cents per contract in 2007. Because the OCC is a utility owned by all the options exchanges, this drop in fees is not due to competition but rather to the reduction in the average cost of clearing a trade in an increasingly electronic world amid rapidly increasing volume.

The mix of trading in all OCC cleared options is about 90% options on individual equities and about 10% options on indexes (see Table 6.1). The CBOE was the market leader and major innovator. Not only was it the first to introduce exchange-traded stock options, it was also the first securities exchange to introduce stock index options. 14 As a result, it was able to negotiate exclusive trading rights on the major indexes early on (the S&P 10015 and S&P 500 in 1983 and the Dow Jones Industrial Average in 1997) and consequently has 85% of the index business. So, index options account for a full 25% of its total options volume, with the other 75% in options on individual equities. Its closest index competitor is AMEX, which has recently been taken over by the New York Stock Exchange and has 5.7% of its total volume in index options. All the other exchanges have 2% or less of their volume in index options.

| Note: AMEX is now part of NYSE Euronext, and PHLX is now part of Nasdaq OMX. | ||||

| *Volume in millions of contracts traded. | ||||

| Source: Options Clearing Corp. Annual Report 2007. | ||||

| Share (%) | Total | Equities | Indexes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBOE | 33.0 | 944 | 714 | 230.5 |

| ISE | 28.1 | 804 | 788 | 16.4 |

| PHLX | 14.3 | 408 | 399 | 8.8 |

| NYSE RCA | 11.7 | 336 | 336 | 0.3 |

| AMEX | 8.4 | 240 | 227 | 13.8 |

| BOX | 4.5 | 130 | 129 | 0.8 |

| Total | 100.0 | 2862 | 2593 | 270.6 |

Even though index options represent a small share of total volume, they are an attractive asset for an exchange. First, exchange fees are higher for customer trades in index options—from 18 to 44 cents per contract compared to 0 to 18 cents per contract for equity options trades. 16 This is not all gravy, since an undisclosed portion of the per-contract fee charged to the customer must be passed on to the index provider. Second, index trades are larger, so the average index trade generates more revenue for the exchange. The average index options trade involves over twice as many options contracts as does the average equity options trade: 44.2 options per index trade compared to 18.9 options per equity trade in 2007. Third, because premiums on index contracts average five times higher—$1,731.30 vs. $332.50 for equity options contracts on single companies—market makers likely earn significantly higher bid-ask spreads, since spreads tend to increase as the value of the option increases.

The Battle over Index Options

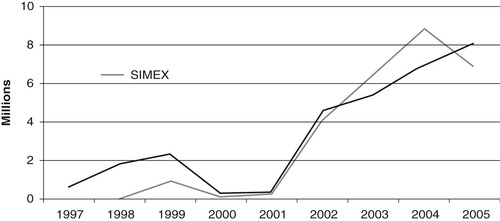

Given the attractiveness of the index option product, even though the ISE had passed the CBOE in options volume on individual stocks (Figure 6.1), it knew that somehow it needed to break the CBOE's hold on trading in stock index options. For several years the ISE simply complained about the CBOT's exclusive right to trade options on the most popular indexes, the S&P 500 and the DJIA. In fact, it adopted the slogan “Free the SPX,” referring to the trading symbol for the S&P 500 option. The CBOE responded with its own slogan imprinted on buttons worn by the members: “Innovation not Litigation.” The CBOE felt that it had created this new class of products called index options, it had made the effort and paid the price to obtain the right to use the trademarked premier brands of the index publishing industry, and it had worked to successfully build the liquidity in these contracts—and here was a newcomer trying to free-ride on all this effort.

But on November 2, 2006, the ISE raised the ante by actually filing a lawsuit on the matter. This was a little less aggressive than the last time the ISE had seen a seemingly proprietary product that it wanted. In 2005, it listed options on two of the most popular exchange-traded funds, 17 SPDRs (based on the S&P 500) and DIAMONDs (based on the DJIA), without obtaining a license from the owners of these two indexes, McGraw-Hill and Dow Jones, respectively. The two indexing companies sued the ISE, but the ISE actually won the lawsuit. 18 There is a difference, though, between an option on an ETF and an option on an index. The CBOE has filed its own suit on the matter against the ISE. To keep things messy, the ISE responded by filing another lawsuit against the CBOE on an unrelated matter. It claims that the CBOE's hybrid trading system, which combines floor and screen-based trading, infringes on ISE patents for its own system.

Global Competition: The Past

SIMEX Was Born Global

There are new forces driving global competition to new heights, but competition across country borders has actually been around for some time. For example, a new financial futures exchange was opened in Singapore back in 1984. Named SIMEX, for Singapore International Monetary Exchange, it began with a handful of products, almost all of which were based on other countries’ markets—not a surprise for an exchange located in a tiny city-state with relatively tiny underlying financial markets. In the same sense that Singapore's economy was based on foreign trade, the products of its futures exchange were based on foreign markets. SIMEX listed four products in its first year: the German mark, the three-month Eurodollar deposit, 19 gold, and the Japanese yen. Even though the German mark and Eurodollars were SIMEX's largest-volume products in some of the early years, Japanese futures would be its bread and butter over the long haul. In those days, the Japanese financial markets were heavily government controlled and were somewhat insular. So the Japanese exchanges were somewhat slow at listing new products, and when they did, it wasn't always the easiest thing in the world for foreigners to gain access to those products. In 1986, before any Japanese exchange had attempted a stock index futures contract, SIMEX filled the gap by listing the Nikkei 225.

The next year, the Japanese government allowed the Osaka Securities Exchange (OSE) to list the first stock index futures contract in Japan, but instead of listing the Nikkei 225, the best-known and most widely followed index of the Japanese markets, the OSE listed a newly made-up (and thus totally unknown) index called the OSF 50, for Osaka Stock Futures. The contract was a short-term solution to a fundamental problem. At the time, Japanese law required that futures contracts result in physical delivery of those contracts not offset prior to maturity, and it thus prohibited the cash settlement of futures contracts. 20 This was not a problem for corn, wheat, or soybeans, which can easily be delivered on a futures contract, but it was a problem for stock indexes, which are very difficult and costly to deliver. Stock indexes are baskets of stocks, and the Nikkei 225 in particular is a basket of 225 different stocks. Because it would require a large number of odd-sized transactions to put together a delivery basket, making it very cumbersome and costly, stock index futures universally use a settlement system known as cash settlement at the expiration of each contract. 21

Without the cash settlement alternative, the Japanese chose the OSF 50 because 50 different stocks would be much cheaper to deliver than 225 stocks. The contract never amounted to much and died within four years. Only 248 contracts of the OSF 50 changed hands in 1987, compared to 586,921 contracts of the cash-settled Nikkei 225 at SIMEX. In the next year, 1988, the law was changed to allow cash settlement, and OSE listed its own cash-settled Nikkei 225. From the very beginning of 1988, the Nikkei 225 at the OSE traded significantly higher volumes than were traded at SIMEX. But SIMEX stayed in the game and was able to increase its trading volume each year until the whole Japanese economy turned south and caused a decline in trading volumes in all Japanese products. Twenty years later, the Nikkei 225 is still the most important product at both SIMEX and the OSE.

Why didn't all the business flow to Osaka, since it had greater liquidity? For one thing, Japan had a system of fixed high commissions—several times the level of SIMEX commissions. Japan's first attempt to fix the high fixed commission problem was unbalanced but logical. The Japanese institutions and individuals were a captive audience, and Japanese brokers didn't want to get rid of that gravy train. But they knew they needed to do something to entice the foreign capital from SIMEX to Osaka, so they kept high fixed commissions for locals but allowed them to be negotiable only for foreigners. Still, there were enough other rigidities and costs in the Japanese system that SIMEX could continue to make a good living by offering an easier, generally cheaper alternative to the Japanese system.

The mid-2008 status of the competition for the Nikkei stock index can be seen in Table 6.2. There has been an extension of the competition between SIMEX and Osaka as each have created several variations on the original product, but there has also been the entry of a new competitor, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange. The CME listed a USD-denominated version of the Nikkei 225 back in 1990 with the thought that a Nikkei based in Chicago with a dollar multiplier would appeal to at least some portion of U.S. investors. It then added a yen-denominated version in 2003, which, as of mid-2008, was doing about the same level of business as the 18-year-old dollar-denominated contract. A number of exchanges have found success in offering smaller retail-sized versions of stock index contracts. In July 2006, the OSE tried the same with the Nikkei 225 mini, which is one-tenth the size of the regular Nikkei 225. Two years later it was trading over twice as many contracts as the full-sized Nikkei (which is, of course, only a quarter of the full-sized contract in nominal traded value). The other thing to note is that in 1994, the Japanese government insisted that a new, better-constructed Nikkei be designed and traded by the Japanese exchange. This was the Nikkei 300, which had 75 more stocks and was capitalization weighted, a generally better way of weighting an index to prevent manipulation. 22 All three exchanges—the OSE, the CME, and SIMEX—listed the 300 just in case it became the new benchmark. The marketplace did not embrace the Nikkei 300 (it preferred the old Nikkei 225 it was used to), and the Nikkei 300 ceased trading at both the CME and SIMEX, but some small degree of volume does persist at the OSE.

About a decade later a similar opportunity presented itself to SIMEX. There had been a growing interest in the Taiwan market, and several exchanges started thinking about listing a Taiwan stock index. The Taiwan regulator had not yet given permission for the local Taiwan exchange to list stock index futures, and neither the stock exchange nor the regulator was keen on allowing an international exchange to list futures on the local TAIEX index. There were, however, other indexes of the Taiwan market aside from the local TAIEX index. The most popular international index of Taiwan stocks was the MSCI Taiwan Index, and both the CME and SIMEX began independently (and unknown to each other) discussing a license with MSCI. 23 After several months of discussion and negotiation, MSCI informed the CME that SIMEX actually had the right of first refusal on any Asian MSCI indexes and had decided to exercise this right with respect to the Taiwan Index. So SIMEX licensed and listed the MSCI Taiwan Index in 1997. The CME was determined to list a futures contract on the Taiwan market, so it turned to Dow Jones, which had its own set of international indexes, though they were not as widely followed. It quickly negotiated a licensing agreement and listed the Dow Jones Stock Index, also in 1997. With two international competitors leaving the gate, the Taiwan regulator allowed the Taiwan Futures Exchange to list its own Taiwan index the following year.

The CME's contract based on the less well-known Dow Jones index lasted only a few months. The real competition was between the Taiwan Futures Exchange and SIMEX. Perhaps because of its one-year head start with an internationally popular index, the Singapore exchange actually outpaced the home market during six of the next eight years (Figure 6.2). In fact, in the most recent data available, the two exchanges traded virtually the same volumes in the regular Taiwan index contract, about 8.3 million contracts in the first half of 2008. The Taiwan Futures Exchange, however, has pulled out ahead, first by adding a mini futures contract, which traded 3.4 million contracts during that same period. But the product extension that really moved the Taiwan Futures Exchange into first place was the option on this index. In a phenomenon that has been observed only in one other market (Korea), the local retail population went crazy over the option on this local stock index. So, during the first half of 2008, there were 46.8 million TAIEX options traded—almost six times the number of regular TAIEX futures. By comparison, SIMEX traded only 137 MSCI Taiwan Index options during that same period.

But SIMEX remains an example of an exchange founded and sustained on the principle of international competition, an exchange that has always derived the overwhelming bulk of its business from international traders trading international products. During the first half of 2008, for example, 92% of SIMEX's futures volume came from products whose underlying assets were tied to other countries, mainly Japan, Taiwan, and India (Table 6.3). Though it also lists Chinese and Pan-Asian indexes, the volumes are inconsequential.

| *Volume January–June 2008 | ||

| **Domestic products | ||

| Source: Futures Industry Association International Volume Report, June 2008. | ||

| Product | Volume* | Share (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Offshore Products | ||

| Nikkei 225 Futures | 11,326,855 | 38.9 |

| MSCI Taiwan Index | 8,358,263 | 28.7 |

| S&P CNX Nifty Index | 6,173,470 | 21.2 |

| MSCI Singapore Index** | 2,335,789 | 8.0 |

| Mini Japanese government bond | 458,333 | 1.6 |

| Euroyen Tibor | 386,112 | 1.3 |

| Mini Nikkei 225 | 31,125 | 0.1 |

| FTSE/China A50 Index | 26,224 | 0.1 |

| MSCI Asia APEX 50 Index | 2,846 | 0.0 |

| USD Nikkei 225 | 2,759 | 0.0 |

| Straits Times Index** | 78 | 0.0 |

| Total futures | 29,101,854 | |

| % of volume based on domestic products | 8.0 | |

| % of volume based on international products | 92.0 | |

Global Competition in Equities Via the Depository Receipt

Global competition in equities has actually been going on for over 80 years. It began in 1927, when J. P. Morgan created the first American Depository Receipt (ADR) for Selfridge's, the big British retailer. What this meant was that Americans who wanted to buy or sell Selfridge's shares no longer had to convert dollars to British pounds and go through a British broker on the London Stock Exchange; rather, they could trade Selfridge's shares denominated in dollars in New York. An ADR allows a non-U.S. company to list its shares for trading in the United States. The way this happens is that a broker in the home country will purchase shares and place them in a local custodial bank that acts as a custodian for an international depository bank, and the broker then instructs the depository bank to issue depository receipts in the United States. These depository receipts, which represent the deposit of domestic shares at the custodial bank in the home country, may be listed and traded on the NYSE, Nasdaq, or any other U.S. exchange, or they may simply be traded in the OTC market. When depository receipts are issued in Europe, they may be traded at a number of different European exchanges as well.

This is an unusual kind of competition because it is not the same as two exchanges listing precisely the same product and going head to head to see which one is able to develop the liquidity. In this case, you have a depository bank, which is essentially transforming a product, the shares issued on a foreign stock market, into something that is more accessible to U.S. and European investors. The domestic shares don't disappear; they are simply transformed into receipts issued in the United States or Europe. Most of the trading that takes place in depository receipts would likely not occur on the home market, whether China, India, Mexico, Brazil, or Australia. This is because the shares on those markets have been transformed into dollar-denominated securities traded under the well-known rules of U.S. or European exchanges, often with greater liquidity than is available in the home market. So, to a large extent, depository receipts really represent the creation of new customers. However, to the extent that some U.S. and European investors would have gone to the trouble to trade these foreign stocks on the foreign home markets, but now choose the convenience of trading the depository receipts on these stocks in the American and European markets, this does represent competition for stock markets worldwide.

The New Global Competition—Kill the Competitor

We explained earlier in this book how technology has been a fundamental driver in the morphing of exchanges during the current era. We also explained how all exchanges are trying to make their way down this steeply falling cost curve, to minimize the cost per share or the cost per contract traded. And, of course, the only way to move down the cost curve is to have more shares or contracts traded at an exchange. Aside from increasing business in existing products and listing new products, the only way to bring more trades to an exchange's platform is to capture business from other exchanges. And there are really two ways to do that. You can capture business by essentially attracting an existing exchange's business to your own exchange, essentially killing the other exchange in the process. Alternatively, you can purchase that business from the other exchange via a merger or acquisition. We turn to the issue of expanding business through mergers and acquisitions in the next chapter.

When pursuing the “kill the competitor” approach, exchanges first tend to go after other exchanges within the same country. Only after that approach has been exhausted do exchanges tend to jump borders and attempt to capture business from exchanges in other countries. And the kill-the-competitor approach works best when the attacking exchange is electronic, and the target exchange is still floor-based. So there's a relatively brief transitional period in the history of exchanges where this approach could work, and that is where electronic and floor-based exchanges exist side by side.

The new global competition has been more prevalent in derivatives than on the equity side of the street. So we start with global competition in derivatives.

Eurex Tries to Kill the Chicago Exchanges

Eurex didn't originally set out to destroy the Chicago Board of Trade. It actually started in October 1999 with a joint venture that was going to help the CBOT move into the electronic age and would help Eurex gain access to U.S. customers. The original deal was called a/c/e, for alliance/CBOT/Eurex, and had the main advantage to the CBOT of replacing the unsuccessful Project A with a first-class electronic trading system. In fact, within a year, on August 28, 2000, the system was up, and the CBOT had, for the first time in its history, both electronic and open-outcry side-by-side trading, allowing customers to choose between the screen and the pit during regular trading hours. Less than two years later, in July 2002, the bloom was off and the two parties announced that they were going to end their alliance in 2004, a full four years before the original 2008 contract expiration. The claim was that the contract was too inflexible and put a damper on contract innovation. Specifically, Eurex was prevented from offering any U.S. dollar-denominated products, and the CBOT was prohibited from listing any European-currency-denominated products. But the CBOT noted at the time of the announcement that Eurex would continue to be a software provider to the CBOT.

Things turned nasty only six months later, on January 9, 2003, when the CBOT announced that it was going to end its relationship with Eurex, dump the Eurex electronic platform, and replace it with the platform offered by Eurex's main European rival, Euronext.liffe. Literally within hours, Eurex chief executive Rudolph Ferscha announced that Eurex planned to go it alone and create an American-based derivatives exchange when its alliance with the CBOT expired at the end of 2003. The exchange would compete directly with the CBOT and CME with futures and options based on bonds, stock indexes, and individual stocks. “Hell hath no fury like a derivatives exchange scorned,” quipped The Economist, and it warned, “if Eurex is even partly successful, there will be more pressure on the Chicago exchanges to give up their mutual structures, merge—and turn their trading floors into museums.”24 This turned out to be a prescient statement.

Eurex actually had two basic options: It could buy or build. Some thought that the quickest way to enter the U.S. market would be by buying an existing exchange with a valid operating license or merging with one. Eurex didn't need a trading platform; it already had a great one that it was using in Frankfurt. And the new law that was passed in 2000, called the Commodity Futures Modernization Act, had streamlined many things, including the process of being designated as an exchange, technically as a Designated Contract Market (DCM). Still, clearing was an issue, and if it bought an exchange, it would need one with a clearing system as robust as the CBOT's external clearing agent, the independent Board or Trade Clearing Corporation (BOTCC). This was because if Eurex was successful, it would soon be doing the same volume as the CBOT and CME combined, since it planned to steal the volume of both. In fact, Eurex decided to build rather than buy an exchange, and it approached BOTCC about clearing for the new exchange.

It is important to remember that Eurex was the exchange that in 1998 essentially captured all the liquidity of the number-one contract traded at the London International Financial Futures Exchange (LIFFE). It was able to do this because it was electronic, transparent, and cheap, whereas LIFFE still engaged in nontransparent, inefficient, and expensive floor-trading. So when Eurex set its sights on Chicago, many people thought this was going to be the end of the CBOT and the CME, which, despite its electronic trading systems, still had significant floor business. So Eurex felt that if it could partner with BOTCC for clearing, get a fast-track approval to be a registered exchange with the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, and train and incent new participants to trade on Eurex in Chicago, its attack on Chicago had a high probability of success. And a number of people in Chicago agreed. Why else would BOTCC have been willing to risk the abandonment of its major client, the CBOT, by agreeing to clear for our Eurex? In fact, BOTCC may have thought it was taking very little risk. BOTCC is controlled by clearing members, who are always looking for ways to reduce the costs of trading. Some competition from a new player could help. And where else could the CBOT go for clearing? Given that three separate attempts to have the CBOT and CME commonly clear their products in one place had failed miserably, BOTCC likely reasoned that while the CBOT wouldn't like BOTCC clearing a new competitor, they would probably stay put. And this would be the best of all worlds for the clearing firms. 25

On September 16, 2003, Eurex held a press conference in Chicago and announced that its Chicago-based subsidiary would be called Eurex US and would initially list the same U.S. Treasury contracts that were listed at the CBOT. Now Chicago was not sitting still. In fact, despite the fact that many observers thought the CBOT would not be able to withstand the Eurex attack, just as LIFFE had not been able to withstand the Eurex attack five years earlier, both the CME and CBOT did everything they could to slow down the opening of Eurex US. They put Eurex's application to the CFTC under a microscope, questioning every possible aspect of the proposal. The advantage of this was that each question required an answer and each answer took time. Because the two Chicago exchanges had courted and funded members of Congress for several decades, the exchanges had access and were able to convince Congressional members to hold hearings on the application. Business Week was more colorful when it noted that despite the exchanges’ usual affirmations of belief in competition and free markets, “Like any favor-seeking sugar grower or steelmaker, the Chicago boys rushed to Washington to sling as much mud as possible at Eurex. Buttonholing such powerful home state pols [politicians] as House Speaker J. Dennis Hastert, they got a hearing on Nov. 6 [2003] before the influential House Agriculture Committee, where they warned that Eurex could threaten everything from open markets to U.S. national interests.”26

As the Chicago exchanges took the battle to Congress, Eurex decided to take the battle to the courts. On October 14, 2003, Eurex filed a lawsuit against the CME and the CBOT for violating antitrust laws. The suit, which was filed in federal court in Washington, D.C., but was later moved to the District Court of Northern Illinois in Chicago, alleged that two exchanges offered shareholders of the BOTCC over $100 million to vote against a restructuring plan that was required for Eurex to be able to clear its products at BOTCC. The suit was amended in December, adding the claim that the two Chicago exchanges’ testimony at congressional hearings was aimed at delaying the launch of Eurex. The suit was further amended in April 2005, over a year after Eurex US listed its first product, to include the claim that the CBOT engaged in predatory pricing by dropping its fees up to 70% only four days prior to the launch of Eurex US. Eurex further alleged that two exchanges had conspired to prevent or delay an important global clearing link between the Clearing Corporation (CCorp) and Eurex clearing in Frankfurt that would have allowed traders to establish a position at Eurex Frankfurt and offset it at Eurex US, or vice versa. 27 When the two Chicago exchanges tried to have the lawsuit dismissed, Judge James Zagel of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois stated, “the Defendants’ [CBOT and CME's] description of Plaintiffs’ Second Amended Complaint bears so little resemblance to the Complaint itself that I paused to consider whether Defendants have actually read the Complaint. Assuming that they have, the characterizations made in Defendants’ briefs are as close to the border of being misrepresentations to this Court as it is possible to come without crossing it.”28 In other words, the judge refused to dismiss the suit.

But the delaying tactics worked. On October 14, 2003, the CFTC announced that it was removing Eurex's application from the 60-day fast track for approval, which would have resulted in a November 15 approval. Moving the application from fast track to normal approval process meant that the CFTC now had until March 16, 2004, to complete the review of the application. 29 Finally, on February 4, 2004, the CFTC approved Eurex US as a Designated Contract Market. Four days later, on February 8, 2004, Eurex US opened its virtual doors for trading.

What did Eurex US have going for it at that time? It had signed up two important Chicago institutions to support it. First, it finally was able to strike an agreement with the Clearing Corporation (formerly known as BOTCC) to clear all Eurex US trades. Second, it enlisted the assistance of the National Futures Association to handle regulatory services for Eurex US. It had in place 36 market makers for the various contracts that it intended to list. And it trained over 100 customers on its electronic trading system.

And what had the two Chicago exchanges been able to do to help fend off the attack? By the time of the Eurex US opening, the CBOT had moved 90% of its Treasury futures trading to the screen and the CME had moved an even greater percentage of its Eurodollar futures trading to the screen. The CBOT had lowered its fees to 30 cents per side for nonmembers on a temporary basis. Since Eurex fees were in the 20 to 30 cents per-contract range, this took away a major part of the fee advantage that Eurex thought it would have going into battle. In addition, the Chicago exchanges had delayed the Eurex launch long enough that the CBOT was able to complete its transition from the Eurex electronic platform to the platform owned by Euronext.liffe, which many observers considered equal to if not better than the Eurex platform. This meant that instead of going to battle with an obsolete, high-priced, nontransparent, floor-based system, Eurex found itself facing an electronic, transparent, low-priced competitor.

Eurex had an uphill battle. By June, Eurex had a very small market share and was not making much forward progress. So it sweetened the pot. On June 22, 2004, Eurex announced that first it would eliminate all fees for trading U.S. Treasury contracts at Eurex US from July 12 through the end of the year; second, it would share up to $40 million in rebates to frequent traders. The plan, which also included stipends paid to market makers to help pay for technology development and free iPods for participating traders, was called X Factor, and it did have an effect. Daily average volume jumped from 2768 contracts in June to 23,922 contracts in July, an impressive 764% increase, but still trivial in terms of market share. At an FIA lunch in Chicago, Eurex US CEO Satish Nandapurkar pleaded with the crowd: “The industry, FCMs and end customers have all been asking for competition … Credible competitive markets exist. But you have to support them. If you do, you send a message. If you don't, you send a message … Your destiny is in your own hands.”30

Over the following months, Eurex tried other things, other incentives and other products, including going after the CME foreign exchange futures, but ultimately the attack failed and Eurex ended up selling 70% of the exchange to Man Group plc for $23.2 million in cash, with Man promising to make a further capital injection of $35 million into the exchange. Despite further injections of cash, by July 2008 Eurex US, renamed USFE, short for U.S. Futures Exchange, was trading only 117 contracts per day, mainly in a dollar-based Indian stock index. The CME, which had absorbed the CBOT and become the CME Group, was trading 990,379 contracts per day—about 8400 times as much. It could have been the other way round.

ICE Tries to Kill NYMEX

Before we describe the battle between ICE and NYMEX, we must first understand what ICE is. Originally, the Atlanta-based Intercontinental Exchange (ICE) opened its doors in 2000 as an OTC energy market for big commercial players. 31 Its founding owners were four investment banks and three big energy companies. From a regulatory point of view, the market was considered an Exempt Commercial Market under the extremely light regulation of the CFTC. When the new futures law was passed in 2000 in the United States, it expanded the types of exchanges that could be created and specifically allowed for several types of very lightly regulated exchanges, which were lightly regulated because only large sophisticated players could participate on them. The Exempt Commercial Market was one of these new exchange types. Over time, ICE acquired futures exchanges in Europe, Canada, and the United States. ICE acquired the London-based International Petroleum Exchange in 2001 and eventually renamed it ICE Europe. In 2007 it acquired both the Winnipeg Commodity Exchange, which it renamed ICE Futures Canada, and the New York Board of Trade, which it renamed ICE Futures US. The original OTC energy business was renamed ICE OTC. So there are four ICE markets: the three futures markets based in Europe, the United States, and Canada and the original ICE OTC market. 32

There was some initial friction between the original ICE OTC market and NYMEX in that some of the business on ICE could have been drawn away from NYMEX and the fact that the ICE used NYMEX futures settlement prices to cash-settle some of its own contracts. NYMEX sued ICE to prevent it from using without permission the intellectual property of NYMEX, but it was unsuccessful because the court ruled that the settlement prices of an exchange are in the public domain.

But the real competition began on February 3, 2006, when London-based ICE Futures (today called ICE Futures Europe) launched a frontal attack by listing a clone of NYMEX's most successful contract—Light Sweet Crude Oil (AKA West Texas Intermediate). NYMEX had frittered away its resources on establishing trading floors in Dublin and London and had plans to do the same in Singapore and Dubai. In the meantime, it had not done much to upgrade its own electronic trading system, mainly used for after-hours trading. This made it very vulnerable to attack from three quarters. First, its energy products would be very attractive to ICE Futures, which was a renamed acquisition by ICE, called the International Petroleum Exchange (IPE). Second, the CME was anxious to diversify into energy contracts and saw NYMEX's business as quite attractive. Third, the now largely electronic CBOT had listed screen-based gold and silver and was eating into NYMEX's gold and silver business on its COMEX division.

The ICE attack was technically cross-border competition because it was a London-based exchange attempting to directly compete with a U.S.-based exchange. At least that is what it looked like on the surface, but the reality was more complex. It is true that ICE Futures was once a British bricks-and-mortar entity, but it had undergone some changes. It switched from being a traditional member-owned exchange and was now a subsidiary of an American, Atlanta-based parent, the IntercontinentalExchange. It also switched trade matching from a trading floor in London to servers in Atlanta. And, with listing WTI crude, virtually identical to the one listed on NYMEX, it now had a U.S.-based product. With American owners, American servers, and American products, to a number of people it was starting to look like an American exchange. Of course, to the Financial Services Authority, the British regulator of all things financial, ICE futures was still a British exchange because the management of the exchange was based in London.

So when NYMEX complained that the competition from ICE was possibly unfair because ICE was subject to different and in some ways lighter oversight than NYMEX, some information-sharing accommodations were made between the two regulators that allowed both regulators to get a much better picture of large traders on both sides of the Atlantic.

But there were two factors that ultimately prevented ICE from killing NYMEX. The major one was that once the CME announced that it also was going to enter the energy business and compete directly with both NYMEX and ICE, NYMEX knew its days were numbered. It was sitting naked with an inadequate electronic platform facing attacks by two aggressive exchanges with well-honed platforms, and ICE had been able to gain a 30% share in a matter of months. One of the three would win this competition, and it wasn't going to be NYMEX, no matter how hard NYMEX members wanted to believe in floor-based trading.

NYMEX had no choice. To survive, it had to make a deal. The immediate deal it made was to move its energy products onto GLOBEX, CME's electronic platform, in return for CME backing down on its plan to list its own energy products. There was a cost—NYMEX had to pay the CME (a fee that is not publicly known), but in making this deal, NYMEX got rid of one competitor and got a first-class electronic platform to use to fight off the other competitor. And it worked. Once GLOBEX became the NYMEX platform, ICE was not able to make further inroads into NYMEX's market share of the WTI market. In fact, the ICE share declined slightly, from 30% to 28%, for the first nine months of 2008, compared with the same period a year earlier.

The second, rather unusual reason that ICE didn't kill NYMEX, is that by doing so it would have been cutting its own throat. The ICE contract does not involve physical delivery, as does the NYMEX contract, but rather is cash-settled. And the price that ICE uses to cash-settle its contract is actually the price established in the NYMEX contract. So if the NYMEX contract disappeared, the ICE contract, as currently structured, could not be settled and would disappear as well. It's not clear how ICE would have kept NYMEX alive had the momentum continued in its favor and the CME not stepped in to save it.

The New Global Competition in Equities

Aside from the ADRs described earlier, there has been little global competition in equities in the United States. Yes, for a number of years New York has been considered a premier place to list stock for companies located all over the world. And these companies sometimes did an IPO and direct listing of its shares in the United States, rather than merely an ADR listing. But unlike the considerable international competition in derivatives allowed by the CFTC, the SEC has allowed foreign exchanges to set up operations in the United States.

In August 2007, for the first time in its long history, the SEC began working on regulations that could allow U.S. investors access to securities traded offshore. 33 The model under consideration is referred to as a mutual recognition model, in which the SEC would allow both broker-dealers and exchanges in other jurisdictions to forgo the registration requirements with the SEC as long as the securities laws, oversight and enforcement powers in their own jurisdiction were comparable to those in the United States. So, instead of complying with SEC regulations, the foreign broker-dealers and exchanges would simply have to comply with the regulations in their own countries, which would be deemed essentially equivalent to complying with SEC regulations. U.S. exchanges insist that if this were to be allowed, the U.S. exchanges themselves should be allowed to list those same foreign products so that investors would have a choice between trading the foreign products on U.S. markets or on the foreign markets. The mutual recognition model had not been implemented at the time this manuscript was submitted for publication, but the fact that the SEC was considering such a bold step suggests that the equity markets may begin to see the same type of global competition that had already begun in the exchange-traded derivatives markets.

The most active cross-border competition in equities has occurred in Europe, which makes sense because Europe makes up the most politically and economically integrated collection of countries on earth. When the European Parliament issued EU Directive 2004/39/EC on markets in financial instruments, it required that a market in financial instruments organize itself in one of two ways: as a regulated market or as a multilateral trading facility. Regulated markets are more like traditional exchanges (think the London Stock Exchange or the Frankfurt Stock Exchange), whereas MTFs are more like the ECNs that started in the 1990s in the United States (think Island, Archipelago, or Instinet, or more recently, BATS Trading or Direct Edge). In fact, just as in the United States, the entry of these new ECNs/MTFs has created a lively competition among platforms for trading the stocks of various European countries, and trading fees at the major exchanges have fallen. Specifically, the price pressure has been due to the entry of such new MTFs as Chi-x, Turquoise, and BATS Trading Europe.

Among the MTFs in Europe, Turquoise announced first in November 2006, but Chi-x Europe started first, in March 2007. Chi-X's speed in getting to market is said to be due to the focus provided by a single dominant shareholder (Instinet). 34 With only the exchanges as competition, Chi-X has absolutely been the low-cost provider of trading services in Europe. This all changed in 2008. Turquoise opened its virtual doors in February 2008. By the time BATS Trading Europe opened in October 2008, Chi-X had a 6.1% share and Turquoise a 1.5% share, all trading in European stocks. BATS got off to a strong start in Europe and may duplicate its performance in the United States. The London Stock Exchange had 19.3%, Deutsche Börse 17.5%, and NYSE Euronext 15.5%. This makes CHI-X the fourth biggest market for European stocks. To add to the competition, NYSE Euronect announced in August 2008 that it would be starting its own MTF for pan-European blue-chip stocks before the end of the year. It planned to use the very fast technology developed by Arca, an ECN converted to an exchange and acquired by the NYSE, and to include SmartPool, a pan-European dark pool for trading large blocks.

The success of the MTFs has been helped by their ownership and business models. Turquoise, for example, is owned by nine investment banks, which made a commitment to provide liquidity for six months. BATS is owned by 10 investment banks and brokers, five of whom are also Turquoise owners. 35 In other words, these two operations are owned by their customers, who have an incentive to drive liquidity to the platform they own. The bottom line is that Europe will continue to see significant intermarket competition for some time, and this cross-border competition should continue to shower benefits on the users of these markets.

Conclusion

As we have seen, there has been some global competition in the equities market going back to 1927, when the first ADR was created, and in the derivatives markets going back to 1984, when SIMEX was founded on products from other jurisdictions. But the pace has quickened as we have moved into an era of electronic trading, and the need to expand the scale has been heightened. The big attempt at cross-border competition in derivatives failed (the Eurex subsidiary in Chicago), but the event did drive the Chicago exchanges to swiftly shift their trading to screens, resulting in some pretty low exchange fees, at least for a while. The very active cross-border competition in European equities should continue to heat up for a few years, pushing down trading fees in Europe just as they have been pushed down in the United States.

Endnotes

1.

2.

3. Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, “Managing the Crisis: The FDIC and RTC Experience 1980–1994,” Washington, D.C., August 1998, p. 547; www.fdic.gov/bank/historical/managing/history2-04.pdf.

4.

5.

6.

7. CBOT member Dan Brophy commenting on FIA president John Damgard's letter on fungibility to the Wall Street Journal; in the John Lothian Newsletter Blog, April 30, 2007; http://johnlothiannewsletter.com/phpbb/viewtopic.php?p=571.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30. Satish Nandapurkur, Speech at FIA Chicago Luncheon, July 29, 2004; www.futuresindustry.org/downloads/divisions/chicago/EurexUS_Speech_July-29-04.pdf.

31.

32.

33.

34. Luke Jeffs and Tom Fairless, “Turquoise pioneer relishes the competition,” Dow Jones Financial News Online, Nov. 17, 2008; www.efinancialnews.com/assetmanagement/pensionfunds/content/3352490930.

35.

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.