3. Floor to Screen: The Second Wave

Executive Summary

The late arrivals to the transition to computer screens had advantages and disadvantages. The biggest advantage was that they did not have to build systems from scratch, as did many of the electronic pioneers. An increasing number of vendors, including other exchanges, were happy to sell or lease various modules of the trading system. The disadvantage faced by the latecomers was that they were late and sometimes at a serious competitive disadvantage. Two large European floor-based exchanges, MATIF and LIFFE, had trouble competing and were subsequently absorbed by others. The last exchanges to the party were seemingly at greatest risk, but one of these latecomers has emerged as the world's biggest derivatives exchange.

Introduction

The first pioneers involved in the shift from floors to screens were individuals or groups who were, for the most part, creating new exchanges. They had no legacy problems. The older pre-existing exchanges were universally floor-based, generally owned by their members, and had little appetite for throwing away their floors and sending their sometimes middle-aged members off to fend for themselves in a technological jungle. For most members, floor-trading was a way of life, often handed down by their fathers before them. Though willing to take calculated risks in the market, floor traders were reluctant to take the risk of transforming their institutions into totally different organizations in which they might not be able to effectively compete. They knew how to survive and prosper on the floor; they doubted they could do nearly as well on a screen, especially competing with younger traders who were raised on videogames and had much faster reaction times.

So, the floor-based exchanges, especially those that were member owned, delayed the transition as long as they could. In some cases, as with the French and the British, the delay cost them their independence. They were both absorbed into other exchanges. In fact, as we learned in the last chapter, the British exchange LIFFE (London International Financial Futures Exchange) lost its cornerstone product to an electronic competitor.

Being late to the electronic trading party was not always bad for the exchanges. Most exchanges around the globe found ways to adapt and make the transition. Early adopters had the advantage of defining the exchange architecture, whereas followers had the advantage of avoiding the mistakes and hurdles pioneers went through. They had the chance to see what worked and what did not. They had far greater choices in technology at a lower cost than did the early adopters. The new vendors were developing applications for the electronic infrastructure. Because the pioneer exchanges had already introduced the concept of electronic trading to financial markets, the followers had less of an educational job before them, aside from convincing their memberships to make the move. They simply had to find a way to make the transition. The path of migration varied in terms of both time and choice of technology. The speed of migration depended on the level of threat exchanges faced in their asset class. Along the way there were some memorable migrations that truly represented the success of electronic trading and the pressure it imposed on the global exchanges. The early adopters’ success in electronic trading was a wakeup call to the rest of the industry. The industry giants in the marketplace resisted the change, banking on their liquidity and touting the floor-trading model as an efficient way of trading.

The last ones to the electronic party were the U.S. exchanges, especially the derivatives exchanges in Chicago and New York, which as late as January 2009 still had active floors, especially in options. Given that the U.S. exchanges dragged their feet even longer than did the French and the Brits, one might think that many of these exchanges would also disappear. In fact, the CME became electronic enough to both fend off competitors and help NYMEX fend off its electronic competitor by allowing it to list its products on the CME's own electronic platform, GLOBEX. Despite the fact that it took such a long time to become substantially electronic, through a combination of solid, consistent leadership the CME ended up taking over both the CBOT and NYMEX, replacing the electronic giant Eurex as the world's largest derivatives exchange. But let's take a closer look at how this second phase played out.

Late Arrivals Get Absorbed

MATIF

MATIF, the Paris-based derivatives exchange, no longer exists. It opened for business as a traditional floor-based exchange on February 20, 1986. Thirteen years later, in 1999, it was absorbed into a group of French exchanges under the name Paris Bourse. A year later the Paris Bourse was itself absorbed into the pan-European exchange called Euronext NV. 1 During its last year as an independent exchange, MATIF became 100% screen-based.

Unlike its Chicago cousins, which have spent the better part of two decades making the shift, MATIF's transition from floor to screen took just over six weeks. This scared the old floor-based markets to death. But the rapidity of the transition was not just a matter of market participants voting with their fingers. It was helped along by the peculiar French habit of addressing all problems with a good, old-fashioned strike.

This is what happened: MATIF announced that on April 3, 1998, the floor and new electronic system would run side by side for the interest rate contracts, which dominated business activity. Fees would be the same on both platforms, giving neither one a fee advantage. Participants would have a choice as to whether they placed orders on the floor or in the computer. It was a hybrid system, and it was up to the market how fast the transition from floor to screen would be.

The first strike occurred on February 2, 1998, about a month before the screen system was due to go live. Locals walked off their jobs for four days to protest the requirements they had to meet to participate on the screen. Volumes fell dramatically, and the strike worked because MATIF cut in half the trading requirement locals needed to meet to get free access to the system. Initially the requirement was 250 contracts per day, but this number was renegotiated down to 125 contracts a day.

Then, in early March, the majority of MATIF's locals went out on a second strike, deciding that they wanted even better terms than they had been granted after the first strike. They also wanted lower fees, even though fees had already been cut in January. They were also upset that a special $8 million fund had been set aside to help brokers make the transition to screens, but nothing similar was done for locals. Again, the strike paid off. The exchange offered, for six months, to waive all trading fees, to provide screens at no cost, and to create a $1.6 million bonus pool for locals to share based on the number of contracts each traded. Despite the offer, many locals remained on strike, demanding tens of millions of dollars more. 2

Because of a hardware problem, there was a five-day delay, and the side-by-side trading of interest rate futures did not begin till April 8. The striking floor locals, through their absence, made it difficult to get trades executed on the floor and made the screen even more attractive than it would have been had the floor been fully open and accessible. By early May, 90% of all interest rate trading was on screen. CAC-40 futures went straight to screen on April 8, and the single stock and CAC-40 options had moved to screen some time before that. In less than seven weeks the market had clearly spoken, and the floor was closed on June 2, 1998. MATIF was now 100% electronic and became the 13th derivatives exchange to become so (see Table 3.1).

The Glitch that Wasn't

There are always glitches in startups, and MATIF had its share, but the exchange got undeservedly bad press for a few weeks that raised concerns on both sides of the Atlantic. On July 23, 1998, the French bond market tumbled when, during a five-minute period, there was a strange series of market sell orders for a total of 10,607 contracts. The Notional bond dropped 149 basis points and then snapped back. All the market orders came from the Salomon Smith Barney office in London. A few trades (for 119 contracts) were busted; most were not. 3

Salomon Smith Barney was one of MATIF's largest clearing firms, so when the firm claimed this activity was due to a bug in MATIF's NSC software, MATIF hired two independent auditing firms to investigate. This was also a sensitive issue because this same NSC software was the foundation for the new, improved version of CME's GLOBEX system.

Even before the investigation was complete, MATIF implemented three changes to prevent a repeat performance. First, it eliminated the “quick trade” button that allowed traders to trade by pressing a single button. Now a trade would take two buttons pressed simultaneously. Second, it created a temporary freeze feature that would halt the market for two minutes if the bond's price ever fell 25% or more. Third, if a very large, unusual market order came into the system, the market would be halted till the exchange could verify it from the trader. This typically took much less than a minute.

When the two independent auditors, CAP Gemini and Kroll Associates, handed over their reports, it was clear that the problem was not in the NSC system but rather had occurred when the London trader inadvertently leaned against the keyboard, sending a flurry of orders. 4

LIFFE

In mid-1997, LIFFE was sitting on top of the world. It had just moved up to become the second largest exchange globally, after the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT) and before the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME). It was a teenager, only 15 years old, and had just surpassed the 99-year-old CME, on which it had modeled itself. It had a great product line, the star of which was the German bund. It was also a bit more aggressive about electronic trading than were the U.S. exchanges. It had been the first exchange in the world to create a screen-based after-hours trading system.

However, LIFFE had not been aggressive enough. As mentioned earlier in this book, Frankfurt-based DTB was doing all the right things to ensure that it was able to bring the bund to Germany. It had effectively placed DTB terminals at practically no cost in the United States, France, and right in the heart of London. As a clear sign of what LIFFE was up against, in late March 1998 one of LIFFE's most prominent members dramatically resigned from the LIFFE board. This board member, David Kyte, one of the biggest floor traders in the bund, said he had no confidence in either LIFFE's chairman or its chief executive. He felt that intense competition the exchange was getting from DTB should cause it to immediately throw the bund onto automated pit trading (APT), the electronic system LIFFE had been using for after-hours trading. There wasn't, Kyte felt, enough breathing room to wait and gradually migrate products over to LIFFE Connect over the next 18 months. DTB already had a greater market share than LIFFE and was breathing down LIFFE's neck.

Though he was spot-on in his forecast, Kyte's own business behavior helped DTB prevail. At the time of his resignation, he had already obtained 50 DTB terminals to allow half the hundred traders in his firm to trade the bund in Frankfurt. If even LIFFE board members were abandoning ship, what chance did LIFFE have?5 Within four months of Kyte's dramatic gesture, both the chairman and the CEO had been sacked or had left the organization.

Despite LIFFE having one of the first after-hours trading systems and despite developing a world-class trading platform in LIFFE Connect, Kyte was right: LIFFE had started too late and got blindsided by DTB. Within nine months of Kyte's resignation from the LIFFE board, DTB had captured 100% of the business in the German bund, LIFFE's flagship product for almost a decade. Three years later, in January 2002, a diminished LIFFE was absorbed by pan-European market Euronext (formed by the merger of the Amsterdam Stock Exchange, Paris Bourse, and the Brussels Stock Exchange).

LIFFE's technology platform, LIFFE Connect, did provide a smooth migration from pit trading to electronic trading. All the markets under Euronext began trading on the LIFFE Connect platform. In addition, the merged Euronext.liffe now sells its technology globally. Today, a number of exchanges utilize LIFFE Connect, such as the Tokyo International Financial Futures Exchange (TIFFE) and, until its 2007 merger with CME, the CBOT.

Last to the Party

The pioneers of electronic trading were almost always new exchanges. There was no cost of or anxiety over conversion. They used screens from day one. And beginning somewhere in the 1990s, all new exchanges adopted the screen-based model. This left the older floor-based, member-owned exchanges, which had put off electronic trading as long as they possibly could. Their embrace of the technology revolution was the most difficult and painful.

The After-Hours Approach

The United States is no technological dwarf. Why, then, did it take so long for the country to get into the screen-based trading game? The answer is simple: U.S. exchanges were owned by their members, by the men and (much less often) women who traded on the exchange floors. The members were making a good living in the old floor system. Why should they throw all this away for a new system that wasn't yet proven and, more importantly, on which they might not be able to compete effectively against a younger generation raised on videogames? The exchanges that would act as pioneers were those without these legacy problems—the new ones, the ones with little to lose.

But the big, member-owned exchanges did put a toe in the electronic waters by adopting limited electronic trading. Specifically, several U.S. and European exchanges, along with the Sydney Futures Exchange, created electronic systems that would be available only after regular trading hours, to solve a different problem and, most important, in a fashion that would not compete directly with their own floors.

This different problem was the need to prevent offshore competition and extend their product monopolies into other time zones as countries in those other zones began to set up their own exchanges. It was an attempt to capture for a given exchange as much of the 24-hour day as possible, or at least the portion of the day in which potential customers were at work. Initially these new exchanges in other time zones would list futures contracts based on their own local equity indexes, their own domestic government debt, and their own commodity products, but there was the chance that they could begin to list U.S. Treasury bonds or Eurodollars or currencies or internationally traded grains or petroleum products and thus compete directly with the big, established U.S. and European exchanges. Even though Japan and other Asian countries were experiencing a financial awakening and were beginning to trade in a big way on the CME, CBOT, LIFFE, and MATIF, these American and European exchanges needed to make their markets accessible during Asian business hours if they expected to maintain this business.

There were at least three ways to extend trading hours and ensure that traders living on the other side of the world would keep trading in Chicago, London, and Paris. The most obvious solution was to simply extend pit trading hours by bringing on a new set of traders to make markets throughout the U.S. or European nights. It was an obvious solution because the physical infrastructure was already there. Just as factories are kept going 24 hours by bringing in three shifts of workers, why not do the same with exchanges? The CBOT actually tried a limited version of this approach with a three-hour evening session for interest rate futures and options in 1987, but it was not successful. The New York Cotton Exchange's (NYCE's) FINEX Division, created for financial instruments, added an evening floor session in 1992, which, amazingly, continued through mid-2007. The problem with night shifts was that not only did the exchange have to attract a new set of fresh traders to the floor, the brokerage firms needed to staff the trading floor booths as well as all other aspects of the trading process. It was a labor-intensive, expensive solution that was ultimately not efficient.

A second approach was to extend trading hours by setting up a trading floor in the targeted time zone. The CME did something close to this in 1984, the same year INTEX set up the world's first fully electronic exchange. It did not actually open its own subsidiary overseas, but it became closely involved with setting up a new exchange in Singapore. Specifically, it established a link with the new Singapore International Monetary Exchange (SIMEX) that tied one of its most important products to an identical product being listed at SIMEX and led to a growth in trading at both exchanges. The product consisted of three-month Eurodollar deposits and the deal, called the Mutual Offset System (or MOS), allowed the CME Eurodollar contract to be traded on the SIMEX floor and then, if the trader wished, his position would be moved to the CME clearinghouse in Chicago and offset on the CME trading floor. In fact, the CME was so committed to establishing a base in the Asian time zone that it actually aided the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) in setting up SIMEX by sending over both staff and traders to train the SIMEX crew.

A more direct attempt to establish a floor in a different time zone was NYCE's attempt to set up a trading floor in Dublin for its FINEX Division's currencies in 1994, which did create a modest amount of business for a number of years. The most recent move in this direction was NYMEX's 2006 creation of a floor-based subsidiary, first in Dublin and later in London, for its energy products. NYMEX's purpose was a little different from NYCE's in that it was attempting to poach some of the experienced traders from a competitor that was replacing its floor with screens. The competitor was the International Petroleum Exchange (IPE), which had been taken over by another closer-to-home competitor, the Atlanta-based Intercontinental Exchange (ICE). Both of NYMEX's attempts to create new European floors failed.

This brings us to the third approach to extending the trading day to protect existing monopolies, and that third approach is after-hours electronic trading. The idea here was to create and use screen-based trading, but only after regular pit trading was done for the day. This avoided any direct screen-to-floor competition and minimized pushback from exchange members currently making their living on the trading floor. So, CME, CBOT and LIFFE products would be available for trading, not only during their own business days, but also during the business days in other time zones. It is worth taking a closer look at some of these after-hours systems.

GLOBEX

Back in the late 1980s both the Chicago Mercantile Exchange and the Chicago Board of Trade viewed the Japanese market as a serious possible threat to Chicago's key contracts. The CBOT, of course, was concerned about its Treasury contracts, and the CME was concerned about its Eurodollar contracts. As mentioned earlier, the CBOT initially took the route of creating a night trading session that began at 6:00 p.m. each evening, right at the beginning of the Japanese business day. The CME took a different route. 6 It made its strategic planning committee's number-one priority the question of how to deal with the broad issue of globalization. Leo Melamed was chairman of the strategic planning committee, and though the CME leader had been, like most U.S. exchange leaders, an outspoken supporter of open outcry against the evils of screen trading, he began to see the value of an electronic solution to the issue of global competition.

The committee developed the idea of extending the trading day, not through an extension of the hours of the physical trading floor but rather via screens that would light up after the pits had closed down. Melamed realized that electronic inroads had been already created in other areas. For example, both the NYSE and the CBOE had established electronic systems for dealing with small retail orders. The London Stock Exchange had undergone the “Big Bang,” described later in this chapter, and closed its trading floor, substituting an electronic quotations system called SEAQ. And of course there was Nasdaq, which had been at least partially electronic ever since its 1971 inception.

There were two marketing tasks associated with the CME's creation of an electronic system for after-hours trading. Naturally, Melamed and others needed to convince the world that the CME's electronic system was the platform of choice for after-hours trading, especially since they had decided to invite other exchanges to participate in GLOBEX. But more important, they needed to convince the members of the exchange, the individual owners who made their living every day in the open outcry pits, that this new electronic system not only did not constitute treason but that it was essential to the future of the CME and its members. Without the members’ vote, there would be no system.

To convince the members, Melamed did two things. First, he knew that he needed to choose an extremely credible and respectable partner to handle the technology for this system; second, he needed to ensure that members would feel both vested in the new system and confident that it would not destroy their floor-based livelihoods. To create credibility, the CME chose Reuters Holdings PLC as the partner. Reuters was a huge international firm with thousands of terminals on traders’ desks all over the world. They had already entered the business of creating markets with the purchase of a company called Instinet, which was an electronic market for stocks traded among large institutions. Reuters had also created a system called Dealing FX, which was an electronic trading system for foreign exchange.

To convince the members that they had nothing to fear, both Leo Melamed and Jack Sandner, then chairman of the CME, promised the members that screen trading would never intrude on regular trading hours without the vote of the membership. To create an incentive for the members and allow them to feel that they were benefiting from the creation of this electronic system, GLOBEX was set up so that a dividend would be paid to the members out of any profits earned by GLOBEX. Specifically, the proposal was that CME members would receive a dividend equal to 70% of the net profits of the operation. The issue of screens was a very sensitive one, and Leo knew that everything had to be just right to gain support from the members. The meeting that was held to unveil the system to the members was preceded by an incredible amount of secrecy. There were to be no leaks. The meeting ended up attracting a huge crowd of more than 1000 members in September 1987.

With presentations from Leo Melamed and Jack Sandner of the CME and Andre Villeneuve and John Hull from Reuters, the members seemed receptive to the idea, and two months later, on October 6, 1987, they approved GLOBEX with a landslide vote. Despite all the good press, it would still take another five years before the electronic trading system was up and running.

It should be noted that GLOBEX was not the first choice of a name for this new system. To emphasize that this was exclusively an after-hours trading system, the name PMT, for Post-Market Trading, was initially chosen. It didn't take long, however, for British friends of the CME to point out that PMT in the United Kingdom had the same meaning as PMS in the United States. Realizing that this would not quite do, the name was changed to GLOBEX, for global exchange.

One thing about GLOBEX was that it strongly emphasized the system being made available to any other exchange that chose to join. Melamed viewed GLOBEX as an industry utility that would have large numbers of exchanges participating in it. The CBOT also sought other exchanges to join its own system, as described shortly. One of the partners that the CME gained was MATIF, the big French exchange.

So after five years of planning and development, the new after-hours system known as GLOBEX finally began on June 25, 1992, with two contracts: the German mark and the Japanese yen. It's always best to start a new system with limited scope so that the financial implications of bugs can be limited and it can be easier to make any repairs that might be needed. A month later, more currencies were added: the British pound, Swiss franc, Australian dollar, and Canadian dollar. In August the CME made its crown jewel, Eurodollar futures and options, available after-hours on GLOBEX. (Eurodollars were three-month deposits of U.S. dollars in banks outside the United States, not to be confused with the currency contract, the Euro FX contract, which was the exchange rate or price of the euro in terms of dollars.)

In February 1997, in a unique technology swap, the CME made a trade with what is now known as Euronext. In this deal, the CME received a state-of-the-art matching engine, known as the Nouveau Système de Cotation (NSC) matching system. It had been developed by the Paris Bourse (the French stock exchange) for MATIF (the French futures exchange that the Paris Bourse had taken over). These two French exchanges had both been absorbed into the pan-European exchange known as Euronext. In return, Euronext received the CME state-of-the-art clearing system known as Clearing 21, which it was able to use to enhance its clearing services.

In that same year, the CME took the first step that would take GLOBEX from a mere after-hours system, accounting for 1–2% of total trading volume, to serving as the platform for virtually all CME trading. Though this full transformation would take over a decade to complete, for the first time in 1997, a contract was launched that would not trade on the floor but would trade only electronically and would be available only during regular trading hours. That contract was the E-mini S&P 500 stock index futures. It was a small version (one fifth the size) of the S&P 500, the mother of all stock index futures contracts. 7

The floor was still nervous about this, and the launch was done with a compromise that orders for trading in the E-mini could not exceed six contracts. This would prevent big traders from shifting their business away from the floor and to the screen. Though the product was a big success and volumes were large, the number of contracts per trade was small, so it was clear that the product was attracting small retail traders. Therefore, the limit on number of contracts per trade was eventually lifted. Two years later, in July 1999, the CME listed its biggest contract, euro dollars, on the screen during regular trading hours, side by side with trading in the pit.

The other thing that the CME did was to make GLOBEX available to other exchanges to list their products. For example, in June 2002, GLOBEX began carrying the e-miniNY crude oil and natural gas futures for NYMEX. Five months later, the single stock futures venture known as OneChicago began using the GLOBEX platform. 8 In 2006, NYMEX began listing its COMEX Division's gold and silver contracts on GLOBEX, to help it defend itself from an attack by the CBOT with its electronic metals trading. Of course, when the CME bought the CBOT in 2007, the agreement required moving all CBOT electronic trading from LIFFE Connect to GLOBEX.

Though GLOBEX was the most ambitious and ultimately the most successful of the after-hours systems, it took a major competitive event to stimulate the rapid migration of Chicago's trading activity away from the floor and onto the screen, an event we will turn to shortly.

CBOT Can't Make Up Its Mind

Leo Melamed says CBOT chairman Karsten Mahlman described GLOBEX as “an H-bomb that threatened the life of open outcry.”9 Needless to say, the CBOT was not happy with GLOBEX. But to stay competitive, the CBOT gathered some impressive partners and went to work on its own after-hours system that would be very different from GLOBEX. The CBOT's “GLOBEX killer” was unveiled on March 16, 1989, at the annual Futures Industry Association Conference in Boca Raton, Florida. The CBOT claimed to be setting new standards for the industry with a system developed by a team made up of Apple Computer Inc., Texas Instruments (TI), and Tandem Computer. The new system, called Aurora, would—with a combination of colorful Macintosh icons contributed by Apple, artificial intelligence contributed by TI, and raw processing power contributed by Tandem—replicate the feel of the floor. 10 Whereas GLOBEX was a system for international brokers, Aurora was a system for pit traders. It was visually much more attractive than GLOBEX. To sweeten the Aurora choice, the CBOT claimed that it would price Aurora at $1 per round turn, compared to GLOBEX’s $4 charge. It should be noted that though Aurora was cosmetically superior, the basic idea of having the screen-based system replicate the floor was already under development at LIFFE in its after-hours system known as APT, for automated pit trading. LIFFE started using APT in November 1989.

Then the CBOT's second reaction to GLOBEX was to join it, or at least to join the CME in discussions about the possibility of combining the two systems for after-hours trading. Actually, the CME made the first move. Leo Melamed and Jack Sandner (CME executive committee chairman and board chairman, respectively) invited Karsten Mahlman and Tom Donovan (CBOT chairman and president) to a private meeting. To keep things quiet, the meeting was held not at the exchange but in the conference room of Melamed's brokerage firm. The CME had a major advantage over the CBOT. 11 The CME's partner, Reuters, was footing the entire bill for building a trading system, which likely cost Reuters about $100 million. The CBOT was paying for Aurora itself, and the costs were mounting. The CME offered to make the CBOT an equal partner in GLOBEX. Remember that at that time the CBOT was still the largest exchange in the world. The offer was good enough for a handshake and a year and a half of discussion leading up to a signed agreement between the CME, CBOT, MATIF and Reuters.

While both exchanges were very ambivalent over this shift to electronic trading, even though it was initially restricted to after-pit hours, the CBOT was the most conflicted. In fact, some on the CME side felt that the CBOT's purpose in joining GLOBEX was to slow it down and kill it. 12 True or not, in April 1994 the CBOT withdrew from the GLOBEX agreement, leaving the CME and Reuters to go it alone. The CBOT exit was also related to an increasing lack of trust and an escalation of competition between the two exchanges. At the same time, the CBOT announced its own new system, which it called Project A. However, Project A, like its predecessor Aurora, would show a trading pit instead of the traditional best bids and offers shown in a ladder format. It was designed to make the floor trader comfortable in the new electronic environment.

In GLOBEX and other systems, matching is done by what is referred to as price/time priority, or first in/first out (FIFO). It's a widespread system because it is logical and fair. When a market order to buy comes into the system and there are a number of offers to sell available for matching, the first ones matched are the best or lowest offers. And within the best offers, whoever put the orders in first gets matched first—the old tradition of first come, first served.

In Project A, the market order still got the best available prices, but the order would be proportionately allocated to all the offers currently available at that best price. The time at which these offers were made was irrelevant. This was consistent with common pit practice, whereby if four locals offer to take the opposite side of an incoming order, each of them receives 25% of the order. There was one way for the online locals to get a bigger share of trades. Anyone who narrowed the spread by putting in a higher bid or lower offer than the best ones currently present would have their entire bid or offer filled before any of the order was allocated to other traders. This feature was included to encourage aggressive bids and offers.

The downside to Project A, just as with the first generation of GLOBEX, was that the trader was chained to expensive Project A hardware. It attracted some business but would have attracted much more had it opened up its architecture. One of the reasons the CBOT did not make huge investments in Project A was likely due to its on-and-off discussions with Eurex that eventually resulted in the CBOT's shift from Project A to a joint CBOT-Eurex platform in August 2000. The new platform carried one of the more awkward names devised for a technology platform: a/c/e, for Alliance/CBOT/Eurex, but people simply called it ace. Luckily the name didn't last long, for in 2003 the CBOT entered into an agreement with LIFFE to license LIFFE Connect for five years. This switch was understandable since EUREX had decided to set up a Chicago subsidiary to compete directly with the CBOT.

Chicago: The Final Push

For almost two decades, the Chicago exchanges, along with NYMEX in New York, walked the difficult path of trying to adapt to the modern world but at the same time protect the livelihoods of their floor-bound members. In other words, the exchanges continued to add technology, but only on the periphery of trading. There were technological improvements in getting orders to the floor, clearing matched trades, and bringing fundamental information and analytical systems to the trading floor. But the execution of trades continued to be done by human beings yelling at one another. That ultimate right of exchange members to execute orders, make markets, and trade against orders, and to do so via hand signals and voice, continued to be preserved as much as possible. Even as electronic trading began to make its way out of the after-hours closet and into regular trading hours, the costs of electronic trades were kept high or speed bumps were constructed to prevent electronic trading from looking too attractive.

But everything changed in the summer of 2003. Eurex, then the biggest exchange in the world, announced that it had plans to open a subsidiary exchange in Chicago, and it began to seek regulatory approval to do so. The Chicago exchanges were scared to death. The smart money was on Eurex. Everyone remembered the battle of the bund, the battle to the death between Eurex13 and the LIFFE. The London-based LIFFE lost the German government bond to the quick, cheap, transparent, screen-based Eurex. And everyone thought that this would be repeated as screen-based Eurex came into Chicago and took on the floor-based CBOT head to head. Now, it's true that the CBOT had its own after-hours electronic system that it had even started to expand to side-by-side simultaneous floor and screen trading, but the overwhelming bulk of trading on the CBOT was still floor-based. In addition, even though the initial attack was to be on the CBOT products—that is, the Treasury futures and options—the CME felt no less threatened. In fact, its fear was well founded, since after an initial sustained attack on CBOT Treasuries, Eurex U.S. did turn its attention to CME currencies.

So together, the Chicago exchanges launched a counterattack. The first thing they did was to throw up every regulatory barrier they could. For example, they ensured that Congressional hearings were held, given the fact that this foreign board of trade, this German exchange, intended to trade in futures and options based on the sacred and precious government securities of the United States. They also did everything they could to slow down the approval process at the Commodity Futures Trading Commission by questioning every single aspect of the application made by Eurex for the new exchange. Second, since what Eurex had going for it was a transparent, electronic, relatively inexpensive system, the Chicago exchanges needed to replicate that as quickly as they could. So the CBOT lowered its fees practically to zero, to match the low fees being charged by Eurex U.S. And both the CBOT and the CME did everything they could to improve their electronic systems and to encourage existing traders to move their business out of the pits and onto the screens so that by the time that Eurex opened its new exchange it would be competing with largely electronic exchanges and not with floor exchanges.

So, while Eurex was dealing with the regulatory hurdles created by the Chicago exchanges, the exchanges took advantage of the breathing room to significantly upgrade their systems. The CBOT had been using a/c/e, a version of Eurex's own system, but was able to migrate its products onto the superior LIFFE Connect platform, so by the time Eurex U.S. was able to open its doors it was at a technological disadvantage. Those who worked on the CBOT and CME upgrades were impressed with the military precision with which both exchanges stuck to their timelines. They had to be on time because the Eurex U.S. launch was imminent. The CBOT completed its migration on January 2, 2004. Eurex U.S. turned on its screens on February 8, 2004, a little over a month later.

It was impossible to become a totally electronic exchange overnight, but a substantial amount of CBOT business was moved onto the screen before Eurex U.S. opened its doors for trading in early 2004. In fact, to the amazement of many observers, the strategy worked. Eurex failed to achieve any substantial share of the U.S. Treasury futures market. The CBOT was able to hang onto its monopoly. When it was clear to Eurex that the attack against the CBOT was going to be unsuccessful, it switched its attention to the CME currencies. Again, the CME had been able to shift such a large portion of its currency trading to the screen that Eurex did not have the advantage that it once had when it stole the German government bond from LIFFE in London.

Though Eurex failed in its attempt to make inroads into the U.S. derivatives space, the competitive threat did wonderful things for the industry. It caused the exchanges to lower their fees. It caused the exchanges to substantially increase the percentage of their trading that was done on screen. So, after almost two decades of playing around with technology on the periphery, the Chicago exchanges moved toward screens in a big way, pushed mainly by one of the biggest competitive threats that they had ever faced in their entire histories. Eurex had done a big favor for Chicago, even though it failed miserably at establishing its own beachhead and had to retreat to Frankfurt with nothing but a lot of bills for the abortive attack.

New York: The Final Push

Chicago has been an electronic backwater compared to the rest of the world, but one good thing that can be said about the city is that it was way ahead of New York. There have been many derivatives exchanges in New York, but in the past decade they were all merged into two: the New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX) and the New York Board of Trade (NYBOT).

NYBOT was a bit of a contradiction. When the World Trade Center was attacked on September 11, 2001, NYBOT was the only exchange that had a physical backup location, and it reopened its trading floor at this Long Island location three days after the attack. However, for an exchange with internationally oriented contracts, NYBOT was surprisingly backward when it came to technology. In fact, it was the only one of the top four U.S. exchanges that had not even set up an after-hours electronic system. It had planned well for a physical disaster but had planned poorly for a competitive disaster. The lesson of an electronic exchange stealing the best product from a floor-based exchange was known to all from the DTB-LIFFE competition we’ve already explored. NYBOT was very much at risk of a screen-based exchange such as ICE, Eurex, Euronext, or the increasingly electronic CME or CBOT picking off its best products.

ICE was the one that made the play for the NYBOT contracts, but it didn't just list coffee, sugar, and cocoa and use marketing and various incentives to win over customers. Instead, ICE bought the products, customers, and liquidity by purchasing NYBOT outright. In this case, it was more than just the products. ICE had been outsourcing clearing, and with the NYBOT purchase, overnight it had its own clearinghouse. It wasn't too bad a deal for the NYBOT members; on the day they voted 93% in favor of the deal, it was worth $1.57 billion ($400 million cash and 10.297 million ICE shares). Divided among the 970 memberships, that came out to $1.6 million per seat, roughly twice the value of four months prior. 14

But NYBOT's failure to create its own electronic platform did result in the virtual disappearance of NYBOT as a brand as its products and clearinghouse were simply absorbed into ICE Futures, ICE's futures subsidiary. It could have been both better and worse. It could have been better if NYBOT had created a viable electronic platform several years before and benefited from the additional trading and revenue that electronic access seems to bring about because of the rise of algorithmic trading. Had NYBOT shifted to screens, demutualized, and launched an initial public offering (IPO), the value created for members could have been much better than what they actually ended up with.

But NYBOT's fate certainly could have been worse. If ICE or another exchange had simply listed the NYBOT products and successfully won the business away from NYBOT, the exchange and its members would have been left with virtually nothing except for a clearinghouse they could sell. So NYBOT should probably consider itself lucky, or more accurately, the former NYBOT members should consider themselves lucky, since there is no longer any NYBOT to consider anything.

NYMEX had moved much further down the electronic path than NYBOT. It first created an after-hours system called ACCESS back in the 1990s. It then upgraded that to a better system called Clearport in 2002, and it had begun using the system during the day for a number of products. But NYMEX had two problems. First, the system was not sufficiently robust to be the workhorse for all of NYMEX's products. Second, NYMEX squandered a lot of time and resources on pursuing a floor-based path in 2005 and 2006. This quixotic venture involved setting up, as previously mentioned, trading floors in both Dublin and London. The original plan for its new exchange in Dubai had it as a floor-based exchange, and it also planned to launch trading on the abandoned SIMEX floor in Singapore.

Having an inadequate electronic system and an unfortunate diversion of management attention devoted to pushing a floor-based expansion into Europe, the Middle East, and Asia left NYMEX highly vulnerable to attack from an electronic exchange. The first such attack came from the most logical place—ICE Futures Europe, the former International Petroleum Exchange, which had arguably become a U.S. exchange, even though it was still regulated in the United Kingdom. ICE Europe, like all the ICE subsidiaries, was lean, mean, innovative, and able to under-price. In February 2006, ICE listed a cash-settled clone of NYMEX's cornerstone product, West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil. To add insult to injury, the cash settlement price ICE chose to use for settling its contract was the most liquid one around: the NYMEX futures price. So ICE didn't really want to kill the NYMEX contract, or at least not do so too quickly. It needed that NYMEX price in the same way that a parasite needs its host. If the host dies, the parasite is out of business.

Things did not look good—and then they got much worse. As ICE's market share for WTI crude oil edged up toward 30%, ICE also launched clones of NYMEX's gasoline and heating oil contracts. Then the CME announced that it was developing its own energy contracts. The born-again largely electronic CBOT decided to launch electronic gold and silver contracts, the major products in NYMEX's metals division. NYMEX's very survival was at stake. NYMEX saved itself only by jumping into the arms of one of its potential competitors—the CME. NYMEX's only choice was to become electronic immediately. LIFFE had lost the bund eight years earlier, in part, because it took too long to move to the screen, and by the time it did, DTB had 100% market share. The only way to become immediately electronic (that is, within a few months) was to outsource, and the only viable quick outsource vendor was the CME's GLOBEX. While the price of renting space on GLOBEX was not made public, NYMEX was not in much of a position to bargain, and it surely paid the price for not being ready with its own system.

Once it was up and running on GLOBEX, NYMEX was able to start taking market share back from ICE on energy and from the CBOT on metals. To help matters, when the CME acquired the CBOT in 2007, it was not able to bring CBOT's gold and silver onto GLOBEX along with the other CBOT products because of CME's commitment to NYMEX. So, NYMEX was pulled back from extinction by the CME, but as explained later in this book, the exchange ended up being acquired by that very same protector.

Stock Exchanges Move to Screens

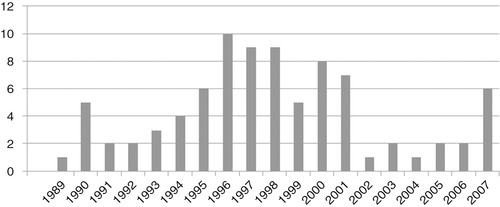

We have told, in great detail, the story of the derivatives exchanges’ gradual shift to screen-based trading. And we did that first because the first electronic derivatives exchange appeared in 1984. Screen-based stock exchanges consistently began appearing a half decade later, in 1989; by that time four electronic derivatives exchanges had already been established. But once the trend started on the equity side of the street, it continued with force. Over the next 20 years (see Figure 3.1), between one and four electronic stock exchanges appeared on the scene each and every year. The peak was from 1995 to 2001, when five to 10 exchanges became electronic each year. After 2001, the number of stock exchanges lighting up screens began to fall off. There was a little pop in 2007 when six exchanges became electronic, including two in Dubai. In August 2008, a rapidly growing ECN called BATS was granted exchange status by the SEC, thus becoming the newest U.S. electronic stock exchange.

Table 3.2 lists all the exchanges we could find that were either born as or converted to electronic exchanges. We found 85. As mentioned earlier, screen-based stock exchanges began in earnest in 1989, but there was a lone outlier pioneer not shown in Figure 3.1. Nine years earlier, in 1980, the little Cincinnati Stock Exchange closed its floor and became the world's first fully electronic stock exchange. Because virtual exchanges can be anywhere, the exchange is today headquartered in Chicago and since 2003 has been called the National Stock Exchange.

| *Originally the Cincinnati Stock Exchange. | ||||

| Source: Mondo Visione, exchange Web sites, communications with exchanges. | ||||

| Exchange | Established | Fully Electronic | Location | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | National Stock Exchange* | 1885 | 1980 | Chicago, United States |

| 2 | Bolsa Electrónica de Chile | November 1989 | November 1989 | Santiago, Chile |

| 3 | OMX Nordic Exchange in Helsinki | 1912 | April 1990 | Helsinki, Finland |

| 4 | Saudi Stock Exchange (TADAWUL) | 1930 | April 8, 1990 | Riyadh, Saudi Arabia |

| 5 | OMX Nordic Exchange in Stockholm | 1863 | 1990 | Stockholm, Sweden |

| 6 | Australian Stock Exchange (ASX) | 1861 | October 1990 | Australia |

| 7 | Shanghai Stock Exchange | November 1990 | December 19, 1990 | Shanghai, China |

| 8 | Warsaw Stock Exchange | 1817 | 1991 | Warsaw, Poland |

| 9 | Stock Exchange of Thailand | May 20, 1974 | 1991 | Bangkok, Thailand |

| 10 | New Zealand Exchange (NZX) | 1915 | August 1992 | Wellington, New Zealand |

| 11 | Shenzhen Stock Exchange | December 1, 1990 | 1992 | Shenzhen, China |

| 12 | Prague Stock Exchange | 1850s | April 1993 | Prague, Czech Republic |

| 13 | Vilnius Stock Exchange | September 1992 | September 14, 1993 | Vilnius, Lithuania |

| 14 | HKEx | 1891 | November 1993 | Central, Hong Kong |

| 15 | National Stock Exchange of India | 1992 | June 1994 | Mumbai, India |

| 16 | Tehran Stock Exchange | 1936 | September 1, 1994 | Tehran, Iran |

| 17 | Istanbul Stock Exchange | October 1984 | November 1994 | Istanbul, Turkey |

| 18 | Borsa Italiana | 1808 | 1994 | Milan, Italy |

| 19 | Indonesia Stock Exchange | 1912 | May 1995 | Jakarta, Indonesia |

| 20 | Lima Stock Exchange | December 31, 1860 | August 1995 | Lima, Peru |

| 21 | Moldova Stock Exchange | December 1994 | October 1995 | Chisinau, Moldova |

| 22 | Ljubljana Stock Exchange | 1924 | December 14, 1995 | Ljubljana, Slovenia |

| 23 | Bombay Stock Exchange | 1875 | 1995 | Mumbai, India |

| 24 | Pune Stock Exchange | 1982 | 1995 | Pune, India |

| 25 | SWX Swiss Exchange | 1850 | 1996 | Zurich, Switzerland |

| 26 | Cyprus Stock Exchange | March 29, 1996 | March 29, 1996 | Nicosia, Cyprus |

| 27 | JSE Limited: SAFEX | September 1998 | May 1996 | Sandton, Republic of South Africa |

| 28 | OMX: Tallinn Stock Exchange | April 1995 | May 31, 1996 | Tallinn, Estonia |

| 29 | JSE | November 1887 | June 1996 | Sandton, Republic of South Africa |

| 30 | Bangalore Stock Exchange | 1963 | July 29, 1996 | Bangalore, India |

| 31 | Mexican Stock Exchange | 1894 | August 1996 | Mexico City, Mexico |

| 32 | Tunis Stock Exchange | 1969 | October 1996 | Tunis, Tunisia |

| 33 | Ludhiana Stock Exchange Assoc. | 1981 | November 1996 | Ludhiana, India |

| 34 | Ahmedabad Stock Exchange | 1894 | December 12, 1996 | Ahmedabad, India |

| 35 | Hyderabad Stock Exchange | November 14, 1943 | February 1997 | Hyderabad, India |

| 36 | Cayman Islands Stock Exchange | June 1997 | June 1997 | George Town, Grand Cayman |

| 37 | Delhi Stock Exchange Association | June 1947 | August 1997 | New Delhi, India |

| 38 | Korea Exchange | March 3, 1956 | September 1, 1997 | Busan, Korea |

| 39 | Osaka Securities Exchange | 1878 | December 8, 1997 | Osaka, Japan |

| 40 | Bhubaneswar Stock Exchange Assoc. | 1989 | 1997 | Bhubaneswar, India |

| 41 | PFTS Stock Exchange | 1997 | 1997 | Kiev, Ukraine |

| 42 | TSX Group | 1852 | 1997 | Toronto, Canada |

| 43 | Tel-Aviv Stock Exchange | 1935 | 1997 | Tel Aviv, Israel |

| 44 | Chittagong Stock Exchange | April 1, 1995 | June 1998 | Chittagong, Bangladesh |

| 45 | Dhaka Stock Exchange | April 28, 1954 | August 1998 | Dhaka, Bangladesh |

| 46 | Regional Stock Exchange West Africa | 1974 | September 16, 1998 | Abidjan, Ivory Coast |

| 47 | Channel Islands Stock Exchange | March 1998 | October 27, 1998 | Guernsey, Channel Islands |

| 48 | Budapest Stock Exchange | June 1990 | November 1998 | Budapest, Hungary |

| 49 | Bermuda Stock Exchange | 1971 | Late 1998 | Hamilton, Bermuda |

| 50 | Kuwait Stock Exchange | 1983 | 1998 | Kuwait City, Kuwait |

| 51 | Muscat Securities Market | 1989 | 1998 | Ruwi, Oman |

| 52 | Namibian Stock Exchange | September 1992 | 1998 | Windhoek, Namibia |

| 53 | Inter-Connected Stock Exch. of India | February 1999 | February 26, 1999 | Maharashtra, India |

| 54 | Tokyo Stock Exchange | 1878 | April 1999 | Tokyo, Japan |

| 55 | Nigerian Stock Exchange | 1960s | April 27, 1999 | Lagos, Nigeria |

| 56 | TSX Venture Exchange | November 1999 | November 1999 | Alberta, Canada |

| 57 | Athens Exchange | 1876 | 1999 | Athens, Greece |

| 58 | Jamaica Stock Exchange | 1961 | February 2000 | Kingston, Jamaica |

| 59 | Amman Stock Exchange | March 11, 1999 | March 2000 | Amman, Jordan |

| 60 | Dubai Financial Market | March 26, 2000 | March 26, 2000 | Dubai, United Arab Emirates |

| 61 | Bahamas Intl. Securities Exchange | September 1999 | May 2000 | Nassau, Bahamas |

| 62 | Irish Stock Exchange | 1793 | June 2000 | Dublin, Ireland |

| 63 | Bulgarian Stock Exchange—Sofia | November 1991 | October 2000 | Sofia, Bulgaria |

| 64 | Luxembourg Stock Exchange | 1928 | November 2000 | L-2227, Luxembourg |

| 65 | National Stock Exchange of Australia | March 2000 | December 5, 2000 | Newcastle, Australia |

| 66 | SWX Europe (formerly virt-x) | 2001 | 2001 | London, United Kingdom |

| 67 | Malta Stock Exchange | January 1992 | 2001 | Valletta, Malta |

| 68 | Macedonian Stock Exchange | September 1995 | April 2001 | Skopje, Macedonia |

| 69 | Egyptian Exchange | 1883 | May 2001 | Cairo, Egypt |

| 70 | Stock Exchange of Mauritius | March 30, 1989 | June 29, 2001 | Port Louis, Republic of Mauritius |

| 71 | Armenian Stock Exchange | February 2001 | July 2001 | Yerevan, Armenia |

| 72 | Nasdaq Stock Market | February 8, 1971 | July 2001 | New York, United States |

| 73 | Oslo Børs | March 1, 1881 | May 2002 | Oslo, Norway |

| 74 | Kyrgyz Stock Exchange | 1994 | May 2003 | Bishkek, Kyrgyz Republic |

| 75 | TLX | September 2003 | September 2003 | Milan, Italy |

| 76 | Belgrade Stock Exchange | 1894 | February 11, 2004 | Belgrade, Serbia |

| 77 | Trinidad and Tobago Stock Exchange | 1981 | March 2005 | Port of Spain, Trinidad |

| 78 | São Paulo Stock Exchange | August 23, 1890 | 2005 | Sao Paulo, Brazil |

| 79 | Boston Stock Exchange | October 1834 | December 2006 | Boston, United States |

| 80 | Philadelphia Stock Exchange | 1790 | December 15, 2006 | Philadelphia, United States |

| 81 | Chicago Stock Exchange | 1882 | February 2007 | Chicago, United States |

| 82 | Dubai International Financial Exchange | September 2004 | August 2007 | Dubai, United Arab Emirates |

| 83 | Borse Dubai | August 7, 2007 | August 7, 2007 | Dubai, United Arab Emirates |

| 84 | Börse Berlin | 1685 | November 2007 | Berlin, Germany |

| 85 | Zagreb Stock Exchange | 1918 | November 23, 2007 | Zagreb, Croatia |

Though most exchanges listed in Table 3.2 (about 80%) are floor-based exchanges that converted to screen-based markets, the remainder (20%) represent exchanges that were created as electronic exchanges. In fact, after the Cincinnati Stock Exchange, which was a conversion from a floor, the second screen-based stock exchange was a new 1989 electronic exchange in Chile, called just that—the Electronic Exchange of Chile (Bolsa Electrónica de Chile). The Shanghai Stock Exchange began as an electronic exchange in 1990. Likewise, the Vilnius Stock Exchange in Lithuania and the National Stock Exchange of India were created as screen-based exchanges out of the box. 15 The Moldova Stock Exchange, the Cyprus Stock Exchange, the Cayman Islands Stock Exchange, and nine others were also begun as electronic exchanges.

Nasdaq: Early, But Not All the Way

The first stock market to move in the direction of screen-based trading was not one of the richer, more sophisticated exchanges such as the New York Stock Exchange or the Tokyo Stock Exchange or the London Stock Exchange but rather the relatively disorganized OTC market in the United States.

The OTC market, of course, was the marketplace for stocks that did not meet the listing standards of the exchanges. It was a dealer market, where from one to 10 or more dealers would make a two-sided market in OTC stocks. Each dealer would quote a price at which he was willing to buy and a price at which he was willing to sell. If a customer told her broker she wanted to buy 1000 shares of a specific OTC stock, the broker would call several dealers to get their quotes and then chose the lowest offer of the three dealers.

Of course, shifting the OTC stock market to screens didn't simply happen but rather was instigated by Congress. It all started because the SEC became concerned about pricing abuses in the OTC market. Because there were a number of brokers trading OTC stocks, there were always different bid-ask spreads available in the market from different brokers for the same stock, and it was virtually impossible, or at least very difficult, for investors to know the best price for a given OTC stock. So the SEC decided to conduct a Special Study of the Securities Market, which it delivered to Congress in 1963. The study argued that the best way to improve price in the OTC market was through automation, and it charged the National Association of Securities Dealers (NASD) to solve the problem by building an automated quotation system whereby its market makers or dealers would post their bids and offers.

The new system, which went live in 1971, was called the National Association of Securities Dealers Automatic Quotation System, or Nasdaq. And it was what its name said—simply a quotation system. To actually buy or sell required a phone call. The only thing automated was the quotes. But this was a positive shift in transparency. Initially only the median bid and offer was displayed for 2500 OTC stocks. It actually took till 1980 before the best bid and offer was displayed on the screen. That was huge and resulted in a significant narrowing of spreads. Now all dealers and brokers could see the best dealer quotes for each OTC stock.

Actual electronic matching began in 1984 with the Computer Assisted Execution System (CAES) but leapt forward the following year with the 1984 introduction of the Small Order Execution System (SOES). However, this was still a dealer market, so SOES was not matching incoming customer orders with each other but rather with the dealer offering the best quote. Furthermore, SOES was not automatic—dealers had the option of responding or not. So, during the crash of October 1987, many small customer orders delivered via SOES were not accepted and went unexecuted. As a result, SOES participation became mandatory for dealers in 1988. Then came a long list of improvements at Nasdaq, including SuperSoes in 2001, which, among many other things, lifted the minimum size of a SOES order to 999,999 shares, and SuperMontage, a system that displayed and allowed execution against the best five bids and offers for every Nasdaq stock on a single screen. The ECNs played a very important role in stimulating this market improvement. Because they were competing with Nasdaq and with each other for order flow, the ECNs were continually improving their systems.

The situation was really Nasdaq's fault. The ECNs were mostly created after the SEC wrote new order-handling rules in 1997. And why did the SEC write new order-handling rules? Because a couple of academic economists, William Christie and Paul Schultz, published a clever article in the Journal of Finance16 (but released the results to the press prior to publication) essentially pointing out that Nasdaq market makers were colluding to earn bigger bid-ask spreads. There were none of the usual tools used to uncover cheating and collusion—no hidden wires, no bugs on phones, no subpoenaed emails—just statistics. Christie and Schultz showed that though the Nasdaq market traded in eighths of a dollar, an archaic thing to begin with in a largely decimalized world, most quotes and trades were done on the even eights, that is, 2/8, 4/8, 6/8, and 8/8 (i.e., a dollar even). If quotes and prices were random, you'd expect about the same percentage of quotes and trades to occur on the odd eights, but the dealers avoided the odd eights like a plague. The effect was to preserve wide 25-cent bid-ask spreads. To put this in the context of today, there are many stocks with bid-ask spreads of 1 cent, so the Nasdaq dealers were engineering spreads 25 times the size of those today. Both the U.S. Justice Department and the SEC got on the case, and the SEC wrote new order-handling rules, which essentially gave birth to the ECN craze and brought a new level of competition to the market. As part of the settlement, Nasdaq agreed to new order-handling rules and to integrate with other ECNs (also known as alternative trading systems). Thus the ECNs played a major role in bringing electronic trading to the equities market in the United States.

In the mid-1990s, the SEC gave ECNs the status of alternative trading systems and permission to integrate with Nasdaq's system. A number of ECNs, such as Instinet, Archipelago, Brut, and Island, entered the equities marketplace. ECNs provided market data (Level 1 and Level 217) to the marketplace beyond traders and market makers at NYSE and Nasdaq. Boosted by the Internet and technological advances in the 1990s, the ECNs evolved into real competition for the two exchange giants. They brought transparency, efficiency, and anonymity to the equities markets and forced the NYSE and Nasdaq to reinvent themselves. By forming partnerships with various discount brokers and investments banks, ECNs made it easier and cheaper for the general public to trade equities. ECNs partnered with online brokerage houses such as E*Trade and Charles Schwab to generate liquidity. By partnering with other ECNs, they linked their order books to provide consolidated liquidity for the whole market. They challenged the rules18 of the primary exchanges and forced the NYSE and Nasdaq to rethink their traditional trading model for the first time. These markets, cognizant of the threat of ECNs, evaluated their option of demutualization, 19 a trend that was already common in European equities market and even in U.S. futures markets. Most ECNs today have been acquired by one of the primary exchanges or by large investment banks, but their innovation and persistence forced the NYSE and Nasdaq to grudgingly plan their survival for the next century.

The competition for electronic trading really heated up with the emergence of ECNs. The competition from ECNs such as Instinet, Island, and Archipelago forced NYSE and Nasdaq, the two dominant U.S. equity exchanges, to rethink their business models. The ECNs challenged the roles of Nasdaq dealers and NYSE specialists, who served as the middlemen for trade matching. Instead, ECNs matched trades automatically on their systems. The ECNs brought anonymity, lower execution costs, and detailed market data to the trading community. Anonymity, for example, has attracted more institutional traders to ECNs. On the floor of the NYSE and in the Nasdaq dealer community there was always a risk of word leaking out about a large order coming in, which could cause the NYSE floor traders or Nasdaq dealers to drive up the price. These leakages do not happen on a computer screen of ECNs where buyer and seller orders are matched by the system. ECNs' lower execution fees, for example, saved institutional investors 1–1.5% on their trades. So, on a $100,000 trade they would save $1000 to $1500. 20 The two market giants looked to purchase the ECNs to maintain their grip on market liquidity. Most ECNs were eventually purchased by these exchanges21 and by some of the larger investment banks. With the acquisition of the ECNs, the exchanges were able to adopt just enough technology to improve their floor-trading but not eliminate the trading flow.

The major transformation of the U.S. equities markets did not occur until recently and only when faced with global competitors and the success of markets in Europe. Nasdaq used the infrastructure acquired from ECNs to provide an electronic trading platform to its customer base. 22 However, the NYSE continued to resist the full transformation to electronic trading. It acquired Archipelago on March 7, 2006, and became a public company. Similarly to CBOE's response to the ISE threat, the NYSE rolled out its hybrid system in October 2006 to quell the pressure of electronic trading. The hybrid system would allow electronic trading to exist in parallel to floor-based trading at the NYSE—and it fared well for a while. According to the exchange, the number of trades executing electronically tripled after the launch of the hybrid system. 23

However, a year later, the exchange once again was facing challenges. The hybrid system in October 2007 was only matching 40% of NYSE listed volume, significantly lower than in the past. 24 New waves of competition from new upstarts such as BATS and Direct Edge as well as from its old rival Nasdaq have continued to challenge the NYSE with their high-speed trading systems and has forced the NYSE to rethink its strategy once again. Today, Nasdaq has expanded globally, with the recent mergers with OMX, the Nordic exchange, and a deal to cooperate with Borse Dubai. The NYSE also merged with Euronext, creating the first transatlantic exchange, and continues to face pressures to complete its migration from floor to screen.

But as we can see from Table 3.2, though Nasdaq was an early adopter of technology, it took 30 years before it gave up the telephones altogether and replaced them with an electronic matching engine for all shares. In fact, the pattern with stock exchanges is similar to that with derivatives exchanges; the exchanges that converted early to full electronic trading were not in the world's financial capitals but rather in more out-of-the-way places like Busan, Santiago, Helsinki, Shanghai, and Riyadh. Furthermore, as in the case of the derivatives exchanges, U.S. exchanges were not leaders but rather laggards when it came to a full adoption of electronic trading.

Toronto

There were other early pioneers, even though they didn't go fully electronic for some time. An important early player in the shift from floors to screens was the Toronto Stock Exchange (TSE). In 1977, it developed a system called CATS, a nice acronym for the more prosaic Computer-Assisted Trading System. CATS was first used for less liquid stocks. It was not uncommon to use electronic matching for marginal situations, such as less liquid stocks in Toronto and Tokyo, or for after-hours trading in derivatives at the CME, CBOT, NYMEX, and LIFFE, or for small orders, as in the DOT and Super DOT system at the NYSE. The TSE has since become a part of a larger exchange group called the TSE Group and uses a new platform, TSX Quantum; in 2008 it announced a new separate order book, TSX Infinity, for high-velocity traders.

Australia

The Australian Stock Exchange, which was created as an association of six different stock exchanges in Australia, was also an early adopter. In 1985 a committee from the exchange took a two-week tour of North American exchanges and came away most impressed with Toronto's CATS system. 25 They came home wanting to use CATS as a model but to build something much faster and more advanced. They spent $1.5 million over the next few years developing the system they called SEATS, for Stock Exchange Automated Trading System.

From a regulatory point of view, it was clear that screen-based trading was highly superior. It created a very transparent audit trail. For example, one of the scams that existed on the Australian floors was something known as the top pocket account. The broker would execute a trade and then put the executed order in his pocket for later allocation. If the market moved up in a significant way, he would execute another trade on behalf of the customer and allocate the first trade to his own account, thereby earning a tidy profit. SEATS would prevent that from happening.

But the exchange got huge pushback from the floor traders, who feared they would lose their edge by no longer being able to make eye contact and read body language. The exchange engaged the members, gave a demonstration of the new system, took some 400 suggestions for changes, made the appropriate changes, held roughly 100 meetings to demonstrate the new system, and then was ready for final rollout. The exchange chose October 19, 1987, as the launch date for the new system for a portion of the listed shares. Yes, that October 19. Of course, on that day all the press the exchange invited to view the wonderful new system became suddenly uninterested in the clever technology. They wanted to find out why the market was dropping like a rock. It was much worse on Tuesday, when the major index, the All Ordinaries, fell 25%.

But the system passed the test, and the exchange stayed open even though neighbor Hong Kong closed both its stock and futures exchanges as a result of the crash. SEATS traded a limited list of stocks side by side with the floor for the next three years. In September 1990 all stocks began to trade side by side. By the end of the month, all six exchanges that make up the Australian Stock Exchange had closed their floors. The system did so well that soon after, the Swiss purchased Australia's system.

London's Big Bang

In some cases the transition was not directly from floor to screen but rather from floor to telephone to screen. When the London markets experienced—or suffered, as might be said by the thousands of workers who lost jobs—the Big Bang of 1986, the London Stock Exchange went electronic in a Nasdaq sort of way. In fact, its electronic system was called SEAQ, for Stock Exchange Automated Quotations system, and was, as its name suggests, a network allowing competitive market makers to post bids and offers on a screen. Because there was no electronic matching system, the actual trades were done via telephone. In principle, the trades could also be done on the floor, but the floor was quickly abandoned and all trading moved to the telephone, just as on Nasdaq at that time. So, in a relatively short period of time, one of the major exchanges of the world essentially became an OTC market. 26

Despite the fact that the new system did not involve electronic trade matching, the combination of the new system along with other market changes resulted in a large increase in trading volume. The other changes included the removal of barriers to entry to the brokerage business from banks and foreigners and the elimination of fixed commissions. Institutional commissions quickly fell 50%, but turnover increased sufficiently to overcome that drop and give the LSE firms an actual increase in income. 27

Just over a decade later, in 1997, the LSE brought in a new electronic platform called SETS (Stock Exchange Electronic Trading Service). And, having developed the habit of making a big change every 10 years, in 2007 it was time for the newest LSE system, called TradElect. In fact, today TradElect manages everything, and within TradeElect is a series of different trading services that utilize the earlier two systems, SEAQ and SETS, as well as some new ones, including an International Order Book for depository receipts. The 20-year-old system, SEAQ, is used for fixed income and stocks on smaller companies and is still a quotation system with no electronic matching.

Conclusion

For well over a century, the physical trading floor was the only venue available to securities and derivatives traders. Technology finally became good enough that the physical location of the trader began not to matter, because everyone could have access to a cyber trading floor. We have come a very long way from 1984, when the first pioneer INTEX opened with fixed lines and dedicated terminals and then closed after a few months. Today there are few exchanges that are still purely floor-based. Most are totally or at least partially electronic.

Though we still have a lot to do, as explained in later chapters, there is no doubt that this first major transformation we’ve explored in this chapter is a net good for the customers of exchanges. They now live in a much more transparent world than their predecessors. They live in a world where it is much cheaper to trade and where it is much less likely that they will be taken advantage of by an intermediary like an unscrupulous floor broker. But, as much as any of the transformations we describe in this book, the floor-to-screen shift is also painful, disruptive, and destructive of jobs and old ways of doing things.

We turn now to the structural and ownership transition that exchanges have often gone through before they were able to make the floor-to-screen transition. We now explore the shift from private club to public company.

Endnotes

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20. Hamilton, “New Electronic Networks Push Big Changes at NYSE, Nasdaq,”; http://articles.latimes.com/1999/jul/30/business/fi-60957July 30, 1999.

21.

22. Nasdaq purchased the Instinet electronic trading platform. The Instinet's brokerage division was bought by Silver Lake Partners, and Instinet's institutional trading division was purchased by the Bank of New York. Matthew Goldstein, “Nasdaq Grabs Instinet ECN,”; www.thestreet.com/markets/matthewgoldstein/10219371.html; April 22, 2005.

23. “NYSE Gets Regulatory Approval for Hybrid Expansion,”; www.finextra.com/fullstory.asp?id=16238; December 6, 2006.

24. “NYSE Can Forget the Hybrid,”; www.nypost.com/seven/10282007/business/nyse_can_forget_the_hybrid.html; October 28, 2007.

25.

26.

27.

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.