5. From Private Club to Public Company

Executive Summary

Member-owned exchanges were the standard model for many years and did a fairly good job. However, an exchange owned by members meant that members often took precedence over customers. In this chapter we explain what a membership is and how those memberships were transformed into a trading right and a bucket of common stock under a process called demutualization, and we review case studies of the CME, CBOT, CBOE, NYMEX, and NYSE. We also explain the drivers behind this important transformation.

Introduction

In this chapter we explore the second of the four basic transformations of the exchanges: the conversion of member-owned exchanges into publicly traded companies. There are really two steps in this process. The first is to convert the exchange from a not-for-profit, member-owned exchange, also called a mutually owned exchange, to a for-profit, stockholder-owned exchange. This process is called demutualization. The second step is to convert the stockholder-owned company into a publicly traded company by issuing shares to the public in a process known as an initial public offering (IPO) and listing the exchange on some stock exchange. Sometimes the exchange even lists itself on itself.

But before we describe the process by which these exchanges became demutualized and publicly traded, we should first take a look at the old form of organization: the member-owned exchange.

The Member-Owned Exchange: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

No exchange is born as a public company. Some are born as joint stock companies, but the majority of exchanges (virtually all those in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Japan, for example) got their start as member-owned mutual organizations. This was an extremely logical choice, given the way exchanges evolved historically. Groups of men (women didn't trade in those days) who traded company stocks or futures-type contracts for corn and wheat wanted to move in from the cold or from the pub or coffeehouse to a more professional trading room. The idea was that the members would own the entity that operated the physical trading room, the blackboards, the telephones, the processing and clearing systems. The exchange would operate as a mutually owned, not-for-profit entity that supported the profit-making objectives of the traders.

Good for the Members

How did the members benefit from the creation of these original member-owned exchanges? The members made their income in three different ways. First, some members acted as floor brokers, and any order coming to the floor had to be executed by one of these floor broker members, for which the member would receive a commission. These floor brokers also benefited if their exchange allowed them to trade for their own account in addition to executing customer orders. While they were not allowed to trade in front of an order they received for one of their customers, knowing the orders in their deck, especially if they handled a lot of orders, gave them an information advantage over traders outside the exchange and even over other floor traders who were not also brokers. Dual traders, especially those with a number of customers or a few large customers, knew a lot more about the potential buying and selling pressure that would arise as the market moved up and down, triggering “price orders” and “stop orders.” (See box, “Market Orders, Limit Orders, Stop Orders.”) U.S. futures exchanges allowed floor brokers to trade for themselves as well as executing orders for customers (a practice known as dual trading), based on the argument that this created more liquidity in the pit. This was true and helpful, especially in smaller pits with a handful of brokers. The only exception to this practice in the futures world was the CME, which prohibited dual trading in liquid markets. While the CBOE earlier allowed its market makers to dual trade, it now also prohibits dual trading.

Market Orders, Limit Orders, Stop Orders and What Floor Brokers Know

In floor-based markets, all orders must generally be executed by floor brokers. Though a number of order types are available for use in floor-trading, there are three basic types of orders used in these markets. First is the market order, which instructs the broker to buy the specified quantity at the best price currently available in the market. This order is used when the trader is mainly concerned about ensuring that the trade is done and is not willing to wait for a possibly better price. Because these orders must be executed immediately, the information they convey to the brokers who fill them is useful for only a matter of seconds. And though a broker might know that a particular order he has received is large enough to move the market when it is executed, it is a violation of exchange rules, CFTC regulations, and the Commodity Exchange Act for brokers to trade for themselves in front of a customer order.

Second is the limit order, which instructs the broker to buy the specified quantity (or as much of it as possible) at a price no higher than the limit specified on the order or to sell no lower than the price specified on the order. Limit orders allow customers to get better prices, but the orders will be executed only if the market rises or falls to the level of the price specified. Floor brokers with big order books thus know something about how much buying there will be if prices fall and how much selling there will be if prices go up. They don't see the whole market, only the orders they are holding, which can still be valuable information.

The third type of order is the stop order. These orders allow traders to specify buy prices above the current market and sell prices below the current market. This type of order is used to get out of the market if it moves too far against a trader. It stops losses from getting any worse. For example, a trader may buy at 10, hoping the market goes to 15, but to ensure that he doesn't lose too much if he's wrong, he may enter a sell stop at 8, meaning that if the market falls to 8, his sell stop gets executed and the most he would lose would be about 2. Though limit orders have the effect of stabilizing the market—if the market starts to fall, the buy limit orders tend to stop the fall by accommodating sellers who come in—stop orders destabilize the market. If the market falls and triggers a sell stop, the sell order joins the other market sell orders flowing in and tends to push down the price even more quickly. So, knowledge of large stop orders can tell a broker quite a bit about how the market will behave if the market rises or falls enough to trigger them.

Second, some members operated as market makers, though they were more commonly called scalpers or locals. What this meant was that they would stand in the pit ready to take the opposite side of incoming orders. If someone wanted to buy, the scalper would sell to them a bit above the last transaction price. If someone wanted to sell, the scalper would buy from them a bit below the last transaction price. The prices at which the market maker would buy and sell were known as the bid and the offer (or the bid and the ask). The difference between these two prices was referred to as the bid-ask spread. The bid-ask spread was the profit made by the scalper for the service of making a market. 1 These scalpers typically would make very small profits on each transaction, since they would be buying slightly lower than the price at which they would be selling, but of course they would experience losses when markets moved unexpectedly. On a traditional floor-based futures exchange, these scalpers did not have an obligation to make a market; they did so as a profit-making business. When things got volatile, they might widen the bid-ask spread to protect themselves or even withdraw temporarily. But the point here is that making markets as scalpers was another way that exchange members could earn revenue.

Third, members often took positions for their own accounts, speculating as to whether the price of some stock or commodity would rise or fall. Being on the floor gave the members an information advantage compared to speculators who were operating from outside the exchange. Floor traders could hear things being said and could see things that traders away from the floor could not. By knowing that an independent floor broker usually did business for a particular large customer, a floor trader could surmise what that customer might be doing. Being on the floor allowed a trader to read the faces of others, to see anxiety, to see panic when a fellow trader or broker was about to offset a huge position that was losing money. In addition, for individuals who traded frequently, the lower exchange fees available to members resulted in significant savings. For example, throughout the 1990s the fees paid by CME members were only one-tenth the level paid by nonmembers (7 cents vs. 70 cents per side). Today the fee structure is more complex and higher than it used to be for members, and the percentage discount for members is smaller, but for frequent traders, there is still a substantial advantage to being a member. For example, to trade indexes on screen at the CME (each product group has its own fee level) a member pays 70 cents a side and a nonmember pays $2.28.

There were, of course, other, less important benefits. For example, the exchange floor provided a certain degree of camaraderie for the members. Compared to the modern world in which isolated traders might be sitting at terminals in disparate places all over the world, the trading floor was the place that the trader went every day, saw the same people, and developed deep and lasting friendships. When a lot of orders were coming onto the floor, life was intense, stressful, and generally profitable. When there were lags in order flow, traders would swap jokes, stories, and news about things both international and personal. For many, it was a fun place to be.

And for most, the trading floor was a much better place to be than an office of a large corporation. The trading floor was populated by essentially independent entrepreneurs. Traders had no bosses. How well they did was a function not of office politics but rather was based on the hard numbers that showed how much money they made or lost at the end of each day. They determined their own destiny, based on their trading skills. And in a larger sense, they determined their own destiny as a group because they owned and controlled the exchange, the place where they worked every day. The mutually owned exchange was a very democratic place. Members elected a board of directors and often the chairman of the exchange as well. 2 The elected board, in turn, created committees of members to handle all sorts of decisions. There were committees for changing the contract specifications of each separate commodity or commodity group. There were committees that dealt with disputes among members. There were committees that dealt with marketing, finance, new products, and even deciding the appropriate clothing for the trading floor.

Managing Regulators

In terms of controlling and protecting the destiny of the exchange and thus protecting the incomes of the members, exchanges would employ lobbyists to attempt to both move forward the agenda of the exchange and prevent damaging actions by central, state, or local governments. These actions would often involve a proposal for a tax of some sort on the transactions conducted at the exchange. It was not uncommon, for example, that the city of Chicago, in its efforts to find new sources of revenue, would talk about taxing transactions on the CBOT and the CME. But typically a combination of strong lobbying and threats to move the exchange elsewhere prevented the imposition of such taxes. On the national level, donations were often made to elected officials, if not by exchanges directly, which is prohibited in some countries like the United States, then from special funds created as member associations and funded by individual members.

The strong relationship between the Chicago exchanges and Congress came in very handy when the exchanges wanted to slow the approval of a Chicago subsidiary of Frankfurt-based Eurex. This event is dealt with in more detail in Chapter 2 and Chapter 6, but because of the relationships that had been created between the Chicago exchanges and various members of Congress, Congress decided to hold hearings on Eurex's application to the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) to set up shop in Chicago. This was a very unusual move—it was the first time in history that Congress held a hearing on an exchange application—but it had the intended effect of delaying the Eurex approval until the Chicago exchanges could better position themselves to fend off a competitive attack. And it worked. The Eurex subsidiary was approved with a significant delay, and it failed miserably.

One political risk faced by derivatives exchanges and their lobbyists is the outright banning of trading in certain products by central governments. In some cases, spot market trade groups might try to shut down trading in a product. For example, onion producers were able to successfully have Congress ban the trading of onions at the CME (and everywhere else in the United States) in 1958 after a manipulation and such a deep crash in prices that the sellers couldn't even recover the cost of the bags the onions were delivered in. The CME fought the ban with a temporary restraining order, even after the President of the United States signed the bill. The exchange eventually gave up, and onions became the only futures contract ever banned by the U.S. Congress.

Almost three decades later, the CME was again faced with an industry-led movement to ban trading in another futures contract, the contract on Live Cattle. 3 In 1984, after years of a government program to support dairy prices by purchasing butter and cheese when their prices fell below a certain critical level, the federal government found itself owning mountains of butter and cheese. It wisely decided to attack the problem at its source: there were simply too many dairy cattle. So the U.S. Department of Agriculture launched the “Whole Herd Dairy Buy Out” and offered to pay dairy farmers who agreed to leave the business and either slaughter or export their entire herds. Market analysts predicted that about a third of a million cattle would be put into the program. When the numbers were finally tallied, a million cattle, three times the predicted amount, were signed up to go to slaughter, significantly increasing the supply of beef (especially hamburger-type ground beef) coming to market and sending prices that were already historically low into a tailspin. Live Cattle futures prices fell by the maximum allowed (called the daily price limit) at the CME for four of the next five trading sessions.

This time the CME tried to work closely with the industry, putting an official from the National Cattlemen's Association on the CME Board, sending CME members and staff to meet with groups of cattlemen all over the country, commissioning studies of the situation, and generally being open to industry ideas to correct any problems. The conciliatory approach with the cattlemen worked. Though the cattlemen were still angry, the CME made enough concessions that they backed off from pushing for a ban on cattle futures. So the exchange, working on behalf of its members, successfully prevented the loss of one of the exchange's most important contracts, again protecting member incomes.

Not all exchanges fare as well in deflecting negative government actions. In India, for example, four commodity futures contracts (wheat, rice, urad, and tur4) were banned in early 2007 and another four (potatoes, soybean oil, rubber, and chana) in early 2008 as a result of a rapid increase in domestic food prices. 5 The fact that this was simply a part of a demand-driven global rise in the prices of physical commodities during that period did not slow down the political decision to ban. Nor did a government report that found that the elimination of futures contracts in 2007 did not halt the continued rise in the spot prices of the banned commodities. So the ban was a visible political action that appealed to people's suspicions that speculative capital had played a role in the price rise. 6 It was intended to show people that the party in power was concerned about the toll that food price inflation was taking on voters all over the country. Part of what this illustrates is that exchanges in India have much less political influence than exchanges in the United States.

One of the other benefits of owning a seat on one of these exchanges was the fact that as business increased, increasing the commission flow to the floor as well as market-making and speculative opportunities, the membership or seat value of the exchange could appreciate significantly. This is because typically the number of seats or memberships at an exchange was fixed. If an outsider wanted to become an exchange member, the only way to do so was to purchase a seat from an existing member. 7 In fact, for some members, their seat value could become a significant portion of their net worth, and retiring members would often retain their seats and lease them for some retirement income.

Member-owned exchanges do have some other advantages. Because the owners were in the building and on the trading floor, they could keep an eye on management, thus minimizing the traditional principal/agent problem, 8 the misalignment of interests between the owners and managers and owners’ lack of information about what management is doing. But as exchanges close their floors and as the member-owners disperse to more comfortable and more interesting places to live, this watchdog effect is largely lost.

Jawboning Liquidity for New Markets

A mutual organization was also important in starting markets for new futures contracts. One of the many obstacles in starting new contracts is to get someone to make liquid markets; otherwise the farmers or bankers or oil companies or hedge funds won't come and play. In the old days, this meant having traders who were making a good living in an established pit to come over and lose money in the new pit, at least for short periods of time. Since a successful new contract pushes up membership prices, owner-members know that sacrifices made today may well be repaid several times over.

Of course it helped to have charismatic leaders remind traders of this fact as they escorted them by their elbows over to the new pit to donate 15 minutes of their time to a new market. This was precisely how the CME got the S&P 500 stock index futures started in 1982. Each member was expected to leave his regular pit and walk over to spend 15 minutes in the S&P pit, and members would be reminded of this by visits from executive committee chairman Leo Melamed and exchange chairman Jack Sandner. The public address system would also remind traders of their obligation with periodic interjections of “Fifteen minutes please, fifteen minutes please.”

Over time this “sacrifice now for the future” approach became harder to sell as exchange floors became increasingly populated by mere renters rather than owners. The problem was created by retiring exchange members who often chose to retain and lease their memberships rather than sell them and face huge capital gains taxes. As any apartment manager knows, renters never take care of places the way owners do, and naturally lessee floor traders were pretty uninterested in making sacrifices to build up new markets that would inflate seat prices and thus the rents they would have to pay. In addition, this technique worked via peer pressure on trading floors. In a screen-based environment, it becomes much less compelling. Exchanges now pay electronic market makers to kick-start new contracts.

Was It Good for the Customers?

Was the nonprofit, member-owned structure a good one? The fact that many of these exchanges have lasted for many decades, some even for centuries, suggests that to a reasonable extent they satisfied both the members and the public customers. But make no mistake: When people join together into associations, they do so to protect their own interests. Exchanges were no different. Exchanges were associations of brokers and traders who wanted to protect and enhance their incomes. And exchanges often provided a good living for multiple generations of families. Fathers would purchase seats for or pass their own seats on to their children when they came of age. One will observe cases where the chairman of an exchange was the son or grandson of a former chairman.

Both stock and derivatives exchanges have generally been regulated by a national (as in the United States, the United Kingdom, and most other countries) and/or regional (as in Germany and Canada) government body to ensure that they don't abuse customers in the pursuit of their own self-interest. 9 In addition, in some countries exchanges are required by law to regulate themselves. This means that the exchange must monitor its members to be sure that they are not taking advantage of their customers. What this means is that members would monitor members and would investigate, charge, and discipline themselves when needed.

Though self-regulation can play an important role, if it really worked well, the CFTC and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) would not have felt it necessary to conduct a sting operation on the floors of the CBOT and the CME during the late 1980s. The seeds of this FBI sting were planted in late 1984, when Dwayne Andreas, the chairman of the giant Archer Daniels Midland Corporation (ADM), complained, through his director of security, to the CFTC in Chicago about abuses on the floor of the CBOT. 10 The CFTC referred the case to the Chicago office of the FBI, which was much better equipped to investigate the alleged abuses. Both the CFTC and ADM helped train four FBI undercover agents on the ins and outs of futures trading. The agents then purchased memberships and spent a couple of years both floor-trading and socializing with traders, wearing hidden recording devices the whole time. During this time, the four FBI agents gathered enough information to charge 48 traders in the soybean, Treasury bond, Japanese yen, and Swiss franc pits at the two exchanges.

The abuses existed for two reasons. First, the open-outcry method of trading is sufficiently nontransparent that it is difficult for those outside the pit to see the cheating occur. Customers, like the chairman of ADM, may suspect they are being cheated, but they really have no way to prove it. Even exchange employees and CFTC staffers are unable to know the instant each trade takes place and whether a particular trade relies on inside information regarding an incoming order.

The second reason customer abuses were going on was that in member-owned exchanges, committees that charged traders with violations and committees that decided penalties for those violations were made up of other members. Though it is true that members better understand floor activities and floor violations than outsiders, they would have an understandable inclination to favor their fellow floor traders over outside customers they don't know. But even if the disciplinary committees conducted their business with pure objectivity, 11 there was still the basic problem that members would have to turn in fellow members whom they saw violating rules—a difficult task in any social group.

Problems with Mutual Exchanges in India: The Government Creates a Demutualized Competitor

This phenomenon of mutually owned exchanges looking mainly after their own members’ interests is not exclusive to the United States. It is the very nature of member-owned business associations to put the interests of their members first. A great example of this tendency and its dangers takes us back to the early 1990s in Indian equity markets. At that time, there were 22 stock exchanges in India, mostly small regional exchanges in places such as Delhi and Kolkata (then called Calcutta). And then there was the Bombay Stock Exchange, more affectionately known as the BSE.

Mumbai (officially renamed from Bombay in 1995) is the financial center of India and is home to all the major financial institutions. Given its Mumbai location, the BSE would naturally capture the bulk of the business; it held a 75% market share, to be exact. Asia's oldest exchange was for years a well-functioning club that produced comfortable results for its members but perhaps less than exceptional service to investors. Commissions were high and transactions anything but transparent. And until the creation of the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) in 1988, the BSE was an unregulated market. In 1992 and 1993, SEBI asked for two very modest reforms—first, to have the BSE brokers register with SEBI, and second, to unbundle commissions from the prices of securities instead of embedding the commission in the price of the security the way OTC dealers do. The brokers balked and went out on strike—not a smart move.

Some visionary leaders within the government decided that the best way to deal with the conflict of interest within mutually owned exchanges was to build a new exchange. It was a bold decision. It was intended to serve as a model for the whole country. And it could create competitive pressure for the BSE to reform itself. To Western free-market ears, this sort of government intervention sounds like a prescription for failure, but the new exchange, the National Stock Exchange of India (NSE), actually turned into a raging success, surpassing the BSE in turnover within its first year. The new start-from-scratch exchange dominated the oldest exchange in Asia in less than 12 months. This success was driven by the following objectives and features12:

• Increase transparency by trading via an electronic limit order book. (BSE was open outcry with market makers.)

• Increase breadth of the market by allowing trading from all over India via satellite technology. (BSE brokers had to be present on the floor of the BSE.)

• Reduce costs (specifically the bid-ask spread) by setting a small and uniform tick size of .05 rupees, about a tenth of a cent. (BSE ticks were 5 to 25 times larger.)

• Reduce investor/broker conflicts of interest by eliminating brokers from governing the exchange. The NSE would be initially owned by public-sector financial institutions, and brokers would not be allowed on the board of directors. (In contrast, BSE brokerage firms owned and ran the BSE.)

A good business plan is not enough. There are thousands that fail. People make the difference. The crack team of five-star performers seconded from the Industrial Development Bank of India, the major public-sector shareholder, did make the difference. They were young, bright, and naive and devoted untold hours and creative energy to making the NSE a success.

Through lower fees, smaller ticks, greater transparency, and truly national reach, the NSE significantly expanded the investor base and the level of trading activity. All the new business initially went to the NSE while the BSE languished. The BSE quickly got the message and embarked on a road of significant reform. The BSE is now also an electronic exchange and has been growing again during the past several years. So the Ministry of Finance's plan worked. The BSE's instinct for self-preservation spurred it to reform itself. It was brilliant.

Cracks in the System: Drivers of Demutualization

The case we just examined was one in which a government created an electronic, for-profit, stockholder-owned exchange as a model to induce other exchanges to demutualize and switch to screens, but most demutualizations across the world are made without any government involvement. There are three main drivers of demutualization. The first is to streamline decision making to better deal with global competition. The second is to allow the exchange to more effectively participate in the mergers and acquisition process by having its own stock to play with. The third is to raise capital and unlock value for the members. Sometimes, in addition, the regulator itself drives demutualization, or I should say requires that exchanges are created as stockholder-owned as opposed to member-owned entities. This was the case when the Indian government decided to set up the stockholder-owned National Stock Exchange in the early 1990s and later required the new national, electronic, multi-commodity exchanges created for trading derivatives on physical commodities to be stockholder-owned. Hong Kong and Singapore authorities each instructed their stock and derivatives exchanges to demutualize and merge.

Democracies have certain advantages. Efficiency, however, is not one of them. Since these mutually owned exchanges needed to include members in the decision-making process, at a minimum they needed to have boards of directors and a chairman who were drawn from and elected by the members. In addition, as exchanges grew, they needed to appoint committees made up of members that would deal with various aspects of the exchange business. For example, there would be a committee for each major product or product group, for facilities, overseeing the behavior of members on the floor, for auditing, for market data services, for marketing, for new product development, and for any number of other issues and tasks that needed to be dealt with. In 1997, the CME had 207 committees, one of which was called the Committee on Committees. In the old days when all exchanges were mutually owned and when competition was local, or at most national, it wasn't such a disadvantage to be a mutually owned exchange. However, as competition moved to the global level and other exchanges became more nimble as stockholder-owned entities, it became a disadvantage to be burdened by an elaborate democratic decision-making process in which large numbers of members were involved.

Another source of inefficiency in the member-owned exchange lay in the fact that decisions were often guided by politics and the desire by board members and chairmen to be reelected. For example, if two or three members out of the whole body of several thousand members were making their living off one small-volume product that was losing money for the exchange, that product would generally not be dropped. The reason, of course, is that these two or three people whose livelihoods depended on the small illiquid market were voters and had many friends on the floor who were voters, and there would be serious complaints if their contracts were pulled out from under them. In other words, the board preserved pockets of inefficiency to keep members happy. Of course, one of the best examples of this is the fact that the floor-based systems were preserved much longer than would have been the case had the exchanges been operated as for-profit stockholder-owned organizations.

In the mergers and acquisitions arena, there is a huge advantage to being stockholder-owned. A member-owned exchange that wanted to acquire another exchange, and this was occasionally done, 13 generally needed cash to pay the members of the target exchange for giving up their ownership rights. But if the acquiring exchange owned stock and could use its stock to purchase another exchange or another business of any kind, it became a much easier task. For one, it is easier to value a for-profit exchange whose stock is traded in the market every day. For another, it's handy to be able to use one's own stock rather than finance a purchase with bank loans.

But demutualization also helps pave the way for electronic trading. Back in the early 1990s, Gerrard Pfauwadel, then Chairman of the Paris-based MATIF, was speaking to a Chicago audience and described their new deal with the then DTB (which would a few years later merge with a Swiss exchange to become Eurex, which was for almost a decade the biggest exchange in the world). The DTB was going to put some of its terminals on the MATIF trading floor and make a couple of DTB products directly accessible to MATIF members. Within a year or so, the MATIF was going to create its own electronic trading system based on the DTB platform. It would then take two of its top products off its trading floor and roll them onto the electronic system to be available to the DTB members.

The audience was incredulous. If the CME or CBOT board took a product away from its members on the trading floor, it would suffer a fate more gruesome than anything seen in the French Revolution, not to mention losing the next election. Mr. Pfauwadel was asked how he could possibly do such a thing and still keep his job. He noted that the MATIF was a corporation owned by a group of banks and that this gave him the flexibility to make decisions that were in the best interest of the exchange. He didn't have to worry about members and floor politics. If the CME and the CBOT were ever going to go fully electronic, it seemed that they would have to first demutualize and pay off the existing members with tradable shares. Though the CME did demutualize and do its IPO before seriously ramping up the screen-based volume, the CBOT was forced to shift much trading to the screen before it demutualized. It was pushed by an even more powerful force: fear of extinction and a direct attack by a major European competitor, the 2004 creation of EurexUS.

First Step: Demutualization

The first step in taking a traditional member-owned exchange to public company status is to demutualize it. Demutualization means the conversion of a mutual, member-owned, not-for-profit organization into a for-profit corporation. So a demutualized exchange is one that was formerly mutually owned but is now stockholder owned. It may or may not have taken the additional step of doing an IPO and becoming publicly traded. An exchange that was originally established as a stockholder-owned one is not demutualized, because it was never mutually owned to begin with, though some observers use the term this way.

The trend was solidly in place by the late 1990s (see Table 5.1). A very interesting poll was conducted during the November 1999 FIBV Bangkok meeting of the world's stock exchanges. 14 Representatives of 50 exchanges were asked if they had already demutualized, had started the demutualization process, or were at least seriously considering the issue. Forty-four, almost 90%, were in one of these three stages.

| *Acquired by Euronext. | |||

| **Acquired by Toronto Stock Exchange. | |||

| ***Acquired by NYSE Euronext. | |||

| Source: Bloomberg and exchange Web sites. | |||

| Founded | Demutualized | IPO and Listing | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stock Exchanges | |||

| OMX Group | 1985 | 1987 | 1993 |

| Borsa Italiana | 1997 | 1997 | None |

| Amsterdam Stock Exchange | 1602 | 1997 | * |

| Australian Stock Exchange | 1987 | 1998 | 1998 |

| Singapore Exchange Ltd | 1999 | 1999 | 2000 |

| Nasdaq Stock Market, INC | 1971 | 2000 | 2002 |

| Toronto Stock Exchange | 1861 | 2000 | 2005 |

| Montreal Stock Exchange | 1874 | 2000 | ** |

| London Stock Exchange | 1801 | 2000 | 2001 |

| Euronext Stock Exchange (Paris) | 2000 | 2000 | 2001 |

| Deutsche Börse | 1993 | 2000 | 2001 |

| Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing | 1947 | 2000 | 2000 |

| Tokyo Stock Exchange, INC | 1878 | 2001 | 2006 |

| Osaka Stock Exchange | 1878 | 2001 | 2004 |

| Oslo Stock Exchange | 1819 | 2001 | 2001 |

| BME Spanish Exchanges | 1995 | 2001 | 2006 |

| Philippine Stock Exchange, Inc | 1992 | 2001 | 2003 |

| SWX Swiss Exchange | 1993 | 2002 | None |

| New Zealand Exchange Ltd | 1915 | 2002 | 2003 |

| Bursa Malaysia | 1930 | 2004 | 2005 |

| Chicago Stock Exchange | 1882 | 2005 | None |

| Dubai Financial Market | 2000 | 2005 | 2007 |

| New York Stock Exchange | 1817 | 2006 | 2006 |

| American Stock Exchange | 1921 | *** | |

| Bovespa Holding S.A. | 1890 | 2007 | |

| Derivatives Exchanges | |||

| Athens Exchange (Hellenic Exchange) | 1876 | 1999 | 2000 |

| Singapore Exchange Ltd. | 1999 | 1999 | 2000 |

| London Metals Exchange | 1877 | 2000 | None |

| CME | 1898 | 2000 | 2002 |

| Sydney Futures | 1972 | 2000 | 2003 |

| Intercontinental Exchange | 2000 | 2000 | 2005 |

| Bursa Malaysia | 1930 | 2004 | 2005 |

| New York Mercantile Exchange | 1872 | — | 2006 |

| BM&F | 1985 | 2007 | 2007 |

| CBOT | 1848 | 2005 | 2005 |

But U.S. exchanges have been considerably behind the rest of the world in this new trend. As with many other things, the Northern Europeans were the first to jump on the demutualization bandwagon, and from 1993 to 1997, exchange demutualization was almost exclusively a European phenomenon. The first exchange to demutualize was the Stockholm Stock Exchange, in 1993. Stockholm split its shares between its members and its listed companies. Part of the deal was that the government rescinded the exchange's monopoly on share trading. Seven years later, on July 1, 1999, the Stockholm Stock Exchange merged with OM Stockholm, the Swedish derivatives exchange, creating the one-stop-shopping OM Stockholm Exchange. The second exchange to demutualize was the Helsinki Stock Exchange in 1995, followed in 1996 by the Copenhagen Stock Exchange and the next year by the Amsterdam Stock Exchange and the Borsa Italiana. The year after that, jumping down to the other hemisphere, the Australian exchange joined suit. In 2000, the Toronto, Hong Kong, and London Stock Exchanges all demutualized.

Another milestone was set by the Australian Stock Exchange, which demutualized on October 13, 1998, and then on the following day became the first stock exchange in the world to list itself on itself. The next year it attempted a merger with the Sydney Futures Exchange (SFE) by offering to exchange $220 million, including $70 million worth of its own shares, for ownership of the SFE. Neither the SFE nor the regulator ultimately thought it was a very good idea, so the deal died, at least for a while. Eight years later, in July 2006, the two exchanges did merge to form the Australian Securities Exchange.

U.S. stock markets lagged behind both their European and Asian cousins. By the time Nasdaq went public in July 2002, most of the major European stock exchanges had already done so: the Swedes, the Greeks, the Norwegians, the Germans, the French, and the English (in that order). And by the time the NYSE went public in March 2006, almost all the major stock exchanges worldwide had already done so. The major exceptions were the stock exchanges of Korea, Taiwan, Spain, Italy, and Switzerland, though the latter three had demutualized.

But why change now? Why did exchanges with their roots going back to the 1800s suddenly find demutualization to be such a cool idea? Why were exchanges like LIFFE, the IPE, the CME, the CBOT, and the NYSE finding the for-profit stockholder model so compelling?

Perhaps there are some clues in the insurance industry, which has been experiencing a strong trend toward demutualization since the early 1990s. Like exchanges, insurance companies often grew out of associations of people with mutual interests. Thus during the Middle Ages, some European guilds began to protect guild members and their families from the economic consequences of the illness or death of the breadwinner. In the countryside, German farmers formed mutual associations to protect themselves from losses due to hail, storms, and fires.

Not only were such mutual insurance associations a natural evolution, they also had an advantage over for-profit corporations. First, neighbors, who deal with each other on a daily basis are not as likely to cheat their mutual association with false claims as they might cheat a for-profit company. Second, with things like life insurance, a policyholder is more likely to trust that his family will be cared for by his guild mates or fellow farmers than by a distant entity that could well go bankrupt before his demise.

And bankruptcy was a real risk. Of all the stock insurance companies operating in the United States in 1868, well over half (61%) had failed by 1905—not very comforting for those who paid monthly premiums for years to protect their families. A New York State commission was set up in 1905 to study these and other scandals of the insurance industry and recommended, among other things, that stock companies convert back to the mutual form of earlier years. Prudential, Metropolitan Life, and the Equitable did just that.

The world is a different place today. Many of these same companies are now reverting to the stock corporation model. The Equitable demutualized and was acquired by the AXA Group in 1992. Metropolitan Life demutualized in 2000. Prudential demutualized and went public in 2001, and a number of other mutual insurers in the United States, Canada, Europe, Australia, South Africa, and Japan have either demutualized or begun the process.

Why are they doing this now? The main motivation seems to be to provide a competitive advantage during a period of industry consolidation. If you want to acquire a competitor or even a financial company in a different line of business, using stock is often better than cash, especially when the stock market is overpriced. When buying an overpriced company, it's much better to pay for it with your own overpriced stock than to use scarce cash. In addition, the owners of the acquired company are able to retain an interest in the new combination and to avoid the taxes associated with a cash sale. As both insurance companies and exchanges saw the mergers and acquisitions begin to take place, they knew that to compete in this game they needed a war chest full of their own stock—the ideal currency for acquisition.

There is a danger in this path. Demutualization is a double-edged sword. The managements of most insurance companies and exchanges typically view themselves as the acquirer. In fact, many of them will turn out to be the acquired. A stock corporation is much easier to take over than a mutual company. In fact, hostile takeovers are virtually impossible with mutually owned companies. It should be noted that “in the public interest,” governments have put restrictions on ownership, especially foreign ownership, of exchanges. The Australian government decided it was not in the public interest to allow any single entity to control the stock exchange and put a 5% limit on ownership by any single person or entity, though the limit was later raised to 15%. 15 The government of India has placed a similar restriction on ownership of Indian exchanges, with 5% limits applying to foreign ownership.

The Demutualization Process

As we said earlier, the demutualization process consists of converting the structure of the organization from one in which the entity is owned by the members to one in which the entity is owned by stockholders and initially those stockholders are the members. After demutualization, the members, or the traders, have trading rights, but they may no longer have any equity rights in the exchange. Different exchanges have taken different routes when implementing this process. However, the key to each of these transactions is that the members give up the old bundle of equity and trading rights and receive in exchange unbundled equity and trading rights. Sometimes the equity rights, as in the case of the planned CBOE demutualization, are completely unbundled, and there is no vestige of an equity right remaining with the trading right. However, in other cases all the members must own equity rights. This can be done, as in the case of the LME, by simply requiring that every member own an equity right in the exchange. The LME requires that each member own a number of class B shares, where that number depends on the class of membership. It can also be done, as in the case of the CME, by literally stapling an equity right to each trading right. In this case, no membership or trading right can be sold without the attached B share, and no B share can be sold without the attached membership or trading right.

The nature of the special equity right in the exchange differs from one place to another. For example, at the CME the B share, which must be attached to every membership, allows one to both receive the same dividends that class A shareholders receive and also gives them much stronger voting rights than A shares do. At the same time, at the London-based LME, the B shares convey neither rights to receive dividends nor rights to vote.

In most cases, demutualization involves the creation of a new entity, a holding company that owns the entity formerly known as the exchange. So CME Group Inc. (formerly CME Holdings Ltd.) owns the CME. Likewise, LSE Holdings Ltd., NYMEX Holdings Inc., and Bovespa Holding S.A. were each the holding company for the associated exchange.

What Is an Exchange Membership?

Traditionally, most exchanges have been structured as mutually owned or membership organizations. Until 2000, almost all U.S. futures exchanges had been owned by their members. 16 These members owned the exchange, and only they could enter the trading floor to trade for customers or trade on their own behalf. In addition, only members received significant discounts off regular rates when trading for themselves. Customers paid much higher rates (as mentioned earlier, the CME charged 7 cents a side to members and 70 cents a side to customers). So a membership was essentially a bundle of two rights: a trading right (a right to be on the floor and trade for their own account or broker trades for others and to receive a fee discount for their own trades) and an ownership right (a partial ownership of the business and the right to vote for the exchange's board of directors, vote in referenda, and serve on committees).

When members got sufficiently old or sufficiently wealthy that they decided to stop trading, they would often hold onto their membership as they would a stock. Like a stock, the membership price would fluctuate in value. And like a stock generating a revenue flow in the form of dividends, the membership generated a revenue flow in the form of lease fees from renting the seat out to individuals who wanted access to the trading floor. In fact, in the process of leasing out a seat, the member was really leasing only the trading right. The ownership right remained with the original member. As mentioned, seat price appreciation has been substantial, and thus this practice of holding onto seats and leasing them out has usually proved a good investment. In fact, in the spring of 1997, 35% of all CME members, 35% of all the International Monetary Market (IMM) members, and 49% of the Index and Option Market (IOM) members were leasing their seats to others. 17

Demutualization and the Transformation of a Membership

The critical question in any demutualization is: how do you divide the value among various participants? It's clear that the member-owners of exchanges and of mutual life insurance companies must be the major beneficiaries of the demutualization, since they were the owners to begin with. But how do you decide how many shares of stock go to each of these participants? In the case of the mutual life insurance companies, the value to be distributed was divided into a fixed component and a variable component. The fixed component was divided among all policyholders on an equal basis. The variable component was divided among the policyholders based on certain attributes of those policies, such as the cash value. The fixed component typically was between 15% and 30% of the total value, and the variable component was the remainder. But international practice varies, and an Australian company put the fixed component at 50% and a U.K. Building Society put it at 100%.

In the case of exchanges, there was a difference between stock exchanges and derivatives exchanges. Stock exchanges have listed companies and members, whereas futures exchanges have only members and listed products; therefore, in some cases, the stock exchanges gave a portion of the shares to the companies that had chosen to list on that stock exchange and a portion of the shares to the members. In the case of the futures exchanges, generally all the shares went to the members in the demutualization. Of course, when the exchange went IPO, the members’ ownership was diluted by the issue of new shares to a new group of investors.

Many exchanges have multiple classes of memberships, each class allowing the members to trade specific groups of products. Because of the different rights associated with each of these memberships, each of the memberships carried a different price or value in the marketplace. So when issuing stock to the members, these different rights and values had to be taken into consideration. In other words, some membership classes received more shares than other membership classes.

Case Study: CME Demutualizes

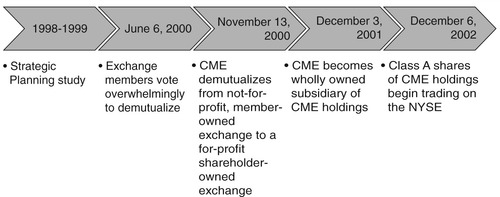

The CME started thinking seriously about converting itself into a for-profit, stockholder-owned exchange back in 1998, when it conducted a strategic planning study on the issue (see Figure 5.1). It decided to move down this path and became the first U.S. financial exchange to “demutualize” ownership (on November 13, 2000) as well as the first U.S. financial exchange to do an IPO and become publicly traded (on December 6, 2002), when it was listed under the ticker symbol CME on the New York Stock Exchange.

The CME's listing history is not a simple one. Two and a half years after its initial listing on NYSE, it decided to also list on Nasdaq. So, beginning May 2005, the CME was dually listed on Nasdaq and the NYSE. It remained dually listed for about three years. Then on July 14, 2008, it dropped its NYSE listing and became exclusively listed on Nasdaq. Why? The CME June 30, 2008, press release on the topic suggested that dropping the NYSE was due to the fact that Nasdaq was experiencing greater volume in CME shares than was NYSE. However, it is also the case that the NYSE, where the CME had carried its original listing, was about to be designated by the CFTC as a futures exchange18 and would become a potential competitor for the CME. In addition, the CME and Nasdaq had another business relationship. The CME leased the right to offer futures and options trading in certain Nasdaq stock indexes and agreed to extend the expiration of the existing contract from 2012 to 2019. 19

The demutualization at the CME involved having members turn in their old memberships and receive new memberships plus a bucket of shares in the exchange. So, the CME memberships were transformed. The old CME membership was a combination of a trading right and an ownership right. Each of the exchange memberships had specific trading rights. For example, the CME seat allowed its holder to trade anything on the floor of the exchange. The IMM seat allowed its holder to trade any financial product at the exchange. The IOM allowed the holder to trade any index or options product. Whatever trading rights existed in the old membership were transferred into the new membership that replaced the old.

Though the CME's new memberships retained the old trading rights, they had virtually all the ownership rights pulled out of them and transferred into the exchange's common stock, called CME A shares. These A shares were given to the members to compensate them for the ownership rights that had been stripped out of the memberships. So before demutualization, the memberships had the traditional bundle of trading rights and ownership rights. After demutualization the memberships had only trading rights and a tiny sliver of ownership rights in the form of one B share. Though the B share paid the same dividends as an A share, its real purpose was to ensure that members still had a significant say in the direction of the exchange (they would elect 30% of the board after demutualization), especially because that direction had an impact on issues critical to members, as we explain in a moment.

The number of shares received depended on the membership class. CME members each got 18,000 shares; IMM members each received 12,000 shares; IOM members each got 1000 shares; and members of the newest and smallest division, the GEM, got a token 100 shares. 20 For each member, all shares but one were A shares. The other was a B share. For example, of 18,000 shares CME members received, 17,999 shares were A shares and could eventually be sold in the marketplace. 21 The remaining share was a B share and remained attached to the CME membership. If a CME membership were sold, the single B share would go with it and the remaining 17,999 shares would remain with the former member, who could retain or sell these shares. This meant that a membership was technically still a bundle of two rights, but the ownership right had become a tiny, tiny fraction of its former self, since most of it had been spun off in the form of A shares. To put this in value terms, at a price of $500 per share, the CME member now had an ownership stake valued at $9 million, of which $500 was still attached to the seat and $8,999,500 was in the form of A shares that could be sold off to interested investors. And as shown in Table 5.2, members of the four divisions of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange were given a total of just under 28.8 million A shares and precisely 3,138 B shares (one for each member). 22

| *As of 1-17-03 following initial demutualization and later conversion into CME Holdings. | |||

| Seats | A Shares | Total A Shares | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CME | 625 | 17,999 | 11,249,375 |

| IMM | 813 | 11,999 | 9,755,187 |

| IOM | 1,287 | 5,999 | 7,720,713 |

| GEM | 413 | 99 | 40,887 |

| Total | 3,138 | 28,766,162 | |

The CME did at least four things to make a demutualized and publicly traded CME attractive for members. First, members were given both common stock and trading rights so that they would now have the choice of continuing to be owner-traders, just owners, or just traders. Second, the members, via their class B shares, were given the right to elect six of the 19 board members. The other 13 board members were elected jointly by both class A and class B shareholders on a share-equivalent basis. Third, the members, also via their class B shares, would be the only ones who would be able to vote on core rights. The core rights included which products could be traded by each membership division, the trading floor access rights and privileges for members, any change in the number of authorized and issued class B shares, and finally, the eligibility requirements for members. 23 And fourth, the members were given a commitment that as long as there were liquid markets on the trading floor, the trading floor would be preserved and supported.

The Economic Value of Demutualized Membership

So, how did things turn out for CME members? They were able to protect themselves from adverse changes to their core rights. They were able to elect 30% of the directors on the CME board. But how did they do financially?Figure 5.2 gives a clue. The chart displays the value of a membership from January 1994 to May 2008. Specifically, it shows the value of a CME membership or seat on the exchange until November 2002, and then beginning in December 2002, the month of the IPO, it shows the value of the membership plus the value of the shares that a CME member received during demutualization. (See Table 5.3 for the relative values of other memberships.) The idea is to show a continuous series reflecting the two rights that members had: a trading right and an equity right. Until demutualization, the two were combined in a seat or membership. After demutualization, membership was essentially a trading right and the equity had been spun off into 17,999 A shares. So the chart shows the sum of the market value of the A shares and the market value of the membership trading right from the IPO on.

|

| Figure 5.2 |

| *Class A & B shares in CME Holdings given November 2000 to existing members. One share of number shown was a B share attached to the trading right; the remainder were A shares, which could eventually be sold in the market. For example, IMM members got 11,999 A shares and one B share. | ||||

| **Transaction dates range from 1/07 to 1/18/2008. 2/16/07. | ||||

| ***With variation, such as IOM trades lumber, GEM trades, GSCI and Russell. | ||||

| Division | Start | Share Given in Demutualization* | Market Price** | Members Can Trade*** |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CME | 1919 | 18,000 | $1,525,000 | Everything |

| IMM | 1972 | 12,000 | $800,000 | All financial products |

| IOM | 1982 | 1,000 | $525,000 | Index futures, all options |

| GEM | 1994 | 100 | $52,000 | Emerging markets and other products |

Let's first look at membership price alone, which is fully shown in Figure 5.2 until the December 2002 IPO. After that it is hidden in the chart as a component of the total value of membership. The mid-1990s was good for CME members. Their seat value hit $925,000 in August 1994. Then seat values slid gradually until they hit a low of $295,000 in December 1998, showing a 68% drop in four years. Prices started rising again and hit another high of $825,000 in April of 2000. They settled back into the mid-700,000s up to demutualization in November 2000, and then they dropped down to $430,000. Even after demutualization, prices slid a bit further to the point that there was a sale in January 2001 for a mere $188,000. Prices then doubled the next year to year and a half and stayed around $400,000 until the IPO in December 2002. Prices then bounced around in the $300,000 to $400,000 range until the summer of 2006, when they started a new rise. In April 2006 there was a sale for $370,000, and then prices rose consistently for the next 20 months until they hit a new peak of $1,550,000 in December 2007, an astounding increase of 319%. So, seat prices can be just as volatile as the prices of the financial instruments traded on the exchange.

Though seat prices had been rising since January 2001, it is the shares that have contributed most to the value of being a CME member. At the CME IPO launch price of $35 a share, the 17,999 shares received by CME members had a market value of $629,965. Over the next five years, the market continued to climb with ups and downs to the point that in December 2007, one share of CME stock went for $686, giving members who still held the shares they received at demutualization a value of $12.3 million and a total value (seat plus shares) of $13.9 million. Even though by May 2008 the stock price had fallen substantially on news that the Justice Department was thinking that the CME and other exchanges should reduce their monopoly power by spinning off their clearing functions, the CME members were still up 47 times from that $188,000 low. The effect of demutualization and the public listing of CME shares has been wildly successful for CME members.

Demutualization and listing its shares on the NYSE and later on Nasdaq was a brilliant move to unlock the value of the ownership portion of exchange memberships. Because the CME could now run as a profit-making enterprise and the audience wanting to own the CME stock was so large, members could sell off the ownership value imbedded in their memberships at very attractive prices and then continue to use the trading rights. Even at a price of $400 per share, a CME member could sell off the ownership rights that were pulled out of his CME membership and imbedded in the 17,999 A shares he was given for $7.2 million and still be left with his transformed membership, worth $1.35 million in May 2008.

CME Demutualization Nuts and Bolts

The CME's demutualization process actually involved two steps. Step one was to merge the existing CME, which was an Illinois not-for-profit membership corporation, into a transitory Delaware non-stock corporation called CME Transitory Co. This step moved the non-stock company known as the CME from Illinois to Delaware. Existing CME memberships were converted into memberships in this new Delaware company. In the second step, which occurred simultaneously with the first step, the Delaware non-stock corporation was merged into a for-profit Delaware stock corporation known as the Chicago Mercantile Exchange Inc. At the same time the memberships in the CME Transitory Co. were converted into shares of common stock in CME Inc. Two classes of shares were issued to members: Class A shares and Class B shares. The initial idea was that Class A shares would be ordinary common stock, and Class B shares would contain both equity and trading rights. This was later changed so that instead of the B share containing the trading and equity right, a new membership was created that contained a trading right with the same privileges as the old membership as well as a single B share, which paid the same dividend as an A share, though it had much stronger voting rights and could never be separated from the membership.

CBOE: An Interesting Speed Bump

The Chicago Board Options Exchange (CBOE) will be the last Chicago exchange to demutualize, as the process was held up for several years by a dispute between the CBOE and CBOT members. The dispute grew out of an ambiguous promise made at the birth of the CBOE. Because the idea for and the founding of this first U.S. options exchange was generated by the CBOT, the 1402 full CBOT members were granted the right to trade on the CBOE without acquiring a separate CBOE membership, though they still had to register and pass a test to be able to do so. These rights, which were included in the CBOE's Certificate of Incorporation, were called Exercise Rights (ER), and many CBOT members did exercise those rights. Though it was clear that the CBOT members had the right to trade, what was less clear was whether they had any equity stake in the CBOE. For many years this was a nonissue. But as the world began to change and exchanges began to demutualize, it became an interesting and economically important problem. In a demutualization, the exchange gives stock to its members in exchange for their membership, though sometimes a new more limited membership is also given. If the CBOE demutualized, would it have to give stock to the 1402 full CBOT members in addition to its own members? If yes, this would create a nice windfall for the CBOT members and significantly dilute the value of the shares received by the CBOE members. Naturally the CBOT felt there was clearly an equity right implicit in the ER and the CBOE argued there wasn't. The CBOE contended that the CBOT's merger with the CME extinguished any exercise right eligibility and even if it had not, the nature and extent of any equity right would have to be determined.

In July 2006, the CBOE set up a special committee to look into this issue and propose a decision as to whether the CBOT members had zero equity rights, full equity rights, or something in between. The CBOT members subsequently sued the CBOE in Delaware court, claiming that they were entitled to equal treatment with the members of the CBOE, should there be a demutualization. However, before the Committee had a chance to complete its work, the CME in 2006 began pursuing a merger with the CBOT, completing it in the summer of 2007. After learning of the merger, the CBOE determined that the merger of the CBOT into the CME essentially eliminated the traditional CBOT memberships and, therefore, no CBOT member would qualify for the Exercise Right. If there were no longer any CBOT members, how could there be any Exercise Rights?

When the CBOT demutualized, it gave three things to former full members of the CBOT: a trading right, some shares, and an exercise right privilege, to allow the holder to trade at the CBOE. In the view of the CBOT, an individual who held all three of these was entitled to receive equity in the CBOE when it demutualized.

The SEC in January 2008 agreed with the CBOE's contention that the CME/CBOT merger effectively eliminated exercise right eligibility. However, there was still the issue of whether other property rights under state law should survive the merger. That issue was referred to the Delaware court, which would convene in June. But before the court could hear either side, in June 2008, the CBOE board reached a settlement agreement with the plaintiff class members and the CME Group, which was now the owner of the CBOT. The agreement included a finding that there were no longer any members of the CBOT eligible to become CBOE members. In return a payment would be made to the class members. In the aggregate, these CBOT members would receive about $1 billion in cash and CBOE stock. Specifically, each class member would receive $300 million in cash, and some would also receive 18% ownership of the CBOE upon demutualization. So the Exercise Right issue was once and for all almost settled. It still needs the blessing of the Delaware court, expected in the first quarter of 2009.

When it comes to the actual demutualization, the CBOE has a somewhat different plan than that of the CME and the CBOT that came before it. The plan will not be implemented until around the time this book is published, so these details are subject to change. The CME, for example, gave its members stock, a trading right, and special voting rights, the latter two preserving their member status very much as it had always been. The CBOE current plan is to give its members only stock—no trading right, no special voting rights. The former members would have to lease a trading right like anyone else if they wanted to trade, and the revenues from the trading rights would become part of the CBOE revenues.

How did the CBOE get away with giving members so much less than the CME did? It may be that the CBOE members have actually chosen a wiser path. The big difference is that about 80% of the CBOE seat holders had leased their seats out to other people who used them to trade on the floor. The members thought of themselves more as equity owners than as floor traders and wanted to ensure that they continued to have a good investment. They were more concerned about returns than preserving their political power. They didn't care about their ability to gain access to the trading floor or about having seats to lease out; they cared mainly about having a good stream of dividends flowing from a well-run, for-profit exchange. And they were convinced that by allowing the exchange itself to manage the number of trading rights as well as the fee for leasing the trading rights, this would be much better than preserving the old system in which each member continued to own the trading right and lease it out for whatever the market would give at that time. In the end, the CBOE would look much more like a modern for-profit exchange, and the CME would look like a mixed corporate structure where the members still exerted significant influence.

CBOT

Though the CME was the first U.S. exchange to demutualize in November 2000, the CBOT was making plans and attempting to get member buy-in for those plans much earlier in the year. Then Chairman David Brennan unveiled an interesting plan to deal with both demutualization and electronic trading simultaneously. The idea was to split the CBOT into two for-profit shareholder-owned companies, one based in the pits and the other based on the screens. The screen-based exchange would utilize the Eurex matching engine that the CBOT had been using. Brennan argued that having separate companies, one of which would be an open-outcry company, would help preserve the open-outcry system for many years to come.

There were a couple of problems with the idea. The first, which would be true for any demutualization, was that there were four classes of CBOT members, and one class in particular, the financial members, who were called associate members, accounted for most of the trading volume but had only a 1/6 vote, compared to a full vote by full CBOT members, who were the guys trading the agricultural products with which the CBOT started. The second problem was that several members felt that a floor-based exchange could not compete with an electronic exchange; therefore, this was simply a trick to convince CBOT members to vote for the plan, which would essentially result in a switch to electronic trading. The plan passed at the board level with a 22-to-1 vote. When a demutualization plan was finally offered to the members, it initially proposed that 88% of exchange ownership be given to full members and 12% be given to the other members; the other members protested and filed suit. They said 12% was too small, given that minority members contribute 60% of exchange volume generated by members. 24 The lawsuit was settled, with the full member share dropping to just under 78% and the other members’ share rising to just over 22%.

The Energy Giant Demutualizes

NYMEX, the world's largest physical commodity exchange, demutualized quite early for an American exchange; in fact, it missed being number one by only four days. The CME demutualized on November 13, 2000, and NYMEX demutualized on November 17, 2000. The old NYMEX was converted from a not-for-profit, member-owned exchange into a Delaware for-profit corporation, wholly owned by NYMEX Holdings, a Delaware for-profit stock corporation. NYMEX initially gave each full NYMEX member two things: a class A membership in the NYMEX exchange (essentially a trading right) and one share of common stock in the newly created NYMEX Holdings (an equity right). 25

Though the CME took only two years before moving to an IPO, NYMEX took six years. Some interesting things occurred during those six years. For example, as NYMEX pursued its quixotic quest to establish unsuccessful floor-based trading venues in Dublin and London, it did so under NYMEX Europe Exchange Holdings Ltd., created in August 2004, which was a wholly owned subsidiary of NYMEX Holdings. This was certainly a money loser for the stockholders. Then in June 2005, NYMEX Holdings entered into a joint venture with Tatweer Dubai LLC to create DME Holdings LLC to launch the Dubai Mercantile Exchange (DME) Ltd. The jury is still out on this venture.

But before going IPO, NYMEX agreed to add a major shareholder. In November 2005, the private equity firm General Atlantic signed a definitive agreement to invest $135 million to acquire 10% of NYMEX Holdings. Though there were other suitors, such as Battery Ventures, NYMEX felt that General Atlantic would best help them prepare for their planned 2006 IPO. The investment was distributed to the 816 NYMEX members, netting each about $165,000. Part of the agreement was to streamline the board, reducing it from 25 to 15 and including General Atlantic President William Ford on the new board.

The NYSE Buys Public Company Status

The NYSE never did an IPO. Instead, it bought Archipelago, which was a publicly traded company at the time, and it used that as a means for making the NYSE a public company. This is how it worked: On March 7, 2006, the NYSE merged with publicly traded Archipelago Holdings Inc. to form the NYSE Group, which began trading publicly the next day. Archipelago, known as Arca in the trading community, was one of the original ECNs, had been a publicly traded company since August 2004, and had acquired a regional stock exchange, the Pacific Exchange, in 2005. The structure was that there was a holding company called NYSE Group Inc. and under the holding company was the New York Stock Exchange LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary, which included the newly merged Archipelago Holdings.

The Last Step: The IPO

The last step in the transition from “private clubs to public companies,” the step that actually takes a company public, is the initial public offering listing on an exchange. The IPOs for exchanges are essentially the same as the IPOs for any other company. Filings must be made with the regulatory body, an underwriter or group of underwriters must be established, the exchange takes its senior officials on a road show to talk to potential investors in the company, the underwriters find investors for the initial offering, an IPO price is established based on the discussions with potential investors, and, on the day following the distribution of shares to these early, often lucky, investors, the company is listed on an established stock exchange and the public can buy and sell the stock for the first time.

The amount by which the new stock closes on the first day of trading above its offering price the night before is a sign of demand for the stock as well as a measure of how underpriced the IPO was. Some first-day moves have been dramatic. For example, when NYMEX went public on November 17, 2006, its stock increased 125% by the close of trading on the first day. That represented a jump from a $59 IPO price to a first-day closing price of $132.99. It was the biggest one-day jump of the year. 26 By contrast, but during the period following the tech bust, the very first financial exchange to go public, the CME, saw a jump of only 23% ($35 to $42.90).

Sometime before the IPO, the underwriters give a range for the IPO price. Sometimes that range is adjusted upward and sometimes downward as the IPO approaches, depending on circumstances. For example, as the Chicago Board of Trade prepared for its IPO in mid-September 2005, it raised the estimated price range for the IPO from the $33 to $36 range, set three months earlier, to a new range of $45–49 for one Class A share. This upward adjustment in the CBOT price appears to have been driven by two things. First, investors were still bullish, given the relatively spectacular rise of the price of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange. In addition, the CBOT had revealed that it had received inquiries regarding a possible merger, and there were rumors that the potential merger partners had suggested bid prices that exceeded the original IPO price range. 27 And when the offering is finally priced, the price is not always inside the estimated range. The CME, for example, had an estimated range of $31 to $34 but priced its IPO at $35.

When shares are sold in an IPO, some shares come from existing owners (generally exchange members who have received common shares in the demutualization in the case of exchange IPOs), whereas others come from stock that has been authorized but not yet issued. For example, when the NYMEX did its IPO in November 2006, 1.1 million shares came from existing owners, including member firms Bear Stearns, Calyon Financial, and Man Group. The remainder of the 6-million-share IPO came from 4.9 million shares that had been authorized but previously unissued. Four years earlier, when the CME went public, over a third of the shares offered were by existing owners. Specifically, 1.75 million shares of the total 4.75 million shares sold by CME came from existing owners. 28

The difference, of course, was that the CME did the very first demutualization and IPO in the United States, so things were less certain. In fact, it was the CME's incredible success, including the fact that the price of CME common stock rose to almost 20 times its initial offering price, that made participants in subsequent demutualizations and IPOs reluctant to part with their shares during the public offering phase. The CME IPO took place less than two years following the technology stock crash in the United States; IPOs had been relatively infrequent ever since the crash.

Because the overwhelming majority of existing owners do not sell their stock, the IPO represents generally a small portion of the total ownership of the firm. For example, NYMEX sold 7% of the company in its IPO.

Conclusion

Like the other trends described in this book, demutualization and public listing have become the norm for financial exchanges worldwide. Those exchanges that have not demutualized typically have been slowed down by some difficult rock in the road, such as the CBOE's dispute with the CBOT over what rights CBOT members continue to have after the CBOT merged with the CME. But these obstacles are gradually being resolved, and within a few years, just as virtually all exchanges will be electronic, virtually all exchanges will also be for-profit, stockholder-owned exchanges.

Endnotes

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6. Two days before the 2008 ban, Finance Minister P. Chidambaram said, “If rightly or wrongly people perceive that commodities-futures trading is contributing to a speculation-driven rise in prices, then in a democracy you will have to heed that voice,” in an interview with Bloomberg Television in Madrid, May 4, 2008. He added, “The pressure is to suspend a few more food articles.”; www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=20601080&sid=aZMFidg5paZI&refer=asia.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15. On October 2000, the Minister for Financial Services and Regulation raised the ownership limit on the Australian Stock Exchange to 15%, noting that any investor wanting to acquire more than 15% would have to apply to the minister and might be approved if such a share was deemed to be in the national interest; www.treasurer.gov.au/DisplayDocs.aspx?doc=pressreleases/2000/065.htm&pageID=003&min=jbh&Year=2000&DocType=0.

16.

17. These are the three major membership divisions of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange. CME stands for Chicago Mercantile Exchange, IMM for International Monetary Market, and IOM for Index and Options Market. Each of these allows trading in fewer products than the one preceding it. Percentage of seats leased taken from a letter to Paul O’Kelly, General Counsel of the CME, from the Federal Elections Commission Advisory Opinion Number 1997-5, May 16, 1997; http://herndon1.sdrdc.com/ao/no/970005.html.

18.

19. Doug Cameron, “CME to List Solely with Nasdaq,” Wall Street Journal, July 1, 2001; http://online.wsj.com/article/SB121485998670417207.html.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.