2. From Floor to Screen: The Electronic Pioneers

Executive Summary

The most important of all the transformations that exchanges are undergoing is the shift from trading floors to trading screens. The earliest electronic exchanges were not conversions of existing floor-based markets but rather brand-new operations like INTEX, the New Zealand Futures Exchange, OM, SOFFEX, DTB, Nasdaq, and the Chinese exchanges. We tell the stories of these early adopters and look for the lessons. The late arrivals to screens, such as MATIF and LIFFE, had trouble competing and were absorbed by others. The last exchanges to the party were at most risk and at one point had been written off, but one of these has emerged as the world's biggest derivates exchange.

Introduction

Beginning in the 1970s and 1980s, innovations in technology developed to such a point that people began to think about bringing traders together without having them meet up on a trading floor every morning. This was especially relevant when traders from several cities all wanted to be part of the trading crowd. Electronic order routing and matching brought people who were geographically dispersed into a single cyberspace where they could signal to each other what they were willing to do. It promised customers a previously unheard-of transparency and a new, significantly lower cost of trading. These efforts began in several places and with different levels of success.

The names of some of the early pioneers are all but forgotten; others have become wildly successful beyond the imagination of the time. These first efforts to create screen-based trading systems were all de novo—new startups. They were not conversions from floor-based exchanges but new exchanges basing themselves on a new electronic model. With no pre-existing structure, there was no baggage and no cost of conversion from floor to screen. The simple question facing the people putting these new exchanges together was how we can best create a new exchange, given our situation and objectives. The choice was between the tried-and-true traditional floor or this relatively untried new approach based on computers and screens. Following the old model was the easiest path. You didn't need to justify it; everyone was doing it. But to deviate required a reason. For Nasdaq, the government made them do it. 1 For INTEX, it was a matter of being fed up with the inefficiencies and abuses on U.S. trading floors. For the Swiss and New Zealanders, it was a way to settle the dispute over where the exchange should be and to avoid the fragmenting of liquidity that would have resulted if multiple exchanges had been created in each country.

But the early adopters of screen-based trading had guts. It was a wonderful experiment, and most often it worked. In some cases, the pioneers were rewarded with spectacular success. In other cases, as in the case of the first real pioneer, the path being blazed came to an unfortunate dead end. We will now visit this first pioneer, a little-known exchange that battled mightily but existed for only a brief period in the mid-1980s. (See the list of derivatives exchanges ranked by the date they became fully electronic in Table 2.1.)

INTEX: The Forgotten First Electronic Derivatives Exchange2

The first fully electronic derivatives exchange is one that almost no one remembers today. No one remembers INTEX because it opened for business over a quarter-century ago and because it was a total failure. No one keeps records on failed ventures, especially old ones. However, it is worth recounting the story of INTEX not only because it was first but also because its failure spotlights an important aspect of the shift from floor to screen—namely, that strong forces have shackled the U.S. exchanges to traditional floor-trading while the rest of the world was speeding ahead in the electronic trading race.

INTEX was born of a personal frustration with the trading floors of the 1970s and 1980s. A futures broker named Eugene Grummer had spent a career at Merrill Lynch and was tired of being abused and poorly treated by the floors of the various exchanges. The pit of a trading floor in the 1980s was not very transparent compared to the modern screen-based market. Say a customer wanted to buy July corn futures at the CBOT. She would know two things: She'd know the price of the last transaction, and if she were speaking directly to the floor, which only larger, more active customers could do, she'd know the last bid and offer. Traders were fond of saying that the bid or offer on a floor was good only as long as the breath was warm—in other words, about a second. So, usually the last bid and offer was not a price at which anyone could necessarily trade. Often the price at which an order was executed would seem to be a little worse than the most recent bid or offer.

And then there were the delays. In those days, when orders came in more rapidly than floor brokers could really handle, a “fast market” was declared by the pit committee and many of the obligations of executing brokers were temporarily waived. It could sometimes take two hours before a customer would know whether his order was executed and at what price. In an extreme case during the bull market in precious metals in 1979 and 1980, the main metals exchange, COMEX (which was later absorbed into NYMEX), was choking on paper. In some cases, customers did not get confirmations that their orders were filled for several days. There were clearly problems with floor-trading.

So Grummer decided that a transparent electronic marketplace would solve many of these problems he had faced for so long. He first needed money, so he raised venture capital from a Texas oilman named Wallace Sparkman. He needed an experienced person to run the company, so he hired as president Junius (Jay) Peake, who had been a partner at the securities firm Shields and Company. Grummer himself became chairman. INTEX was born in 1981, though it would be several years before the first trade took place.

Grummer and Peak wanted to start the exchange within the United States. That's where they resided and where most of their potential customers lived. So they went to see the federal derivatives regulator, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC). The result was not good. They were told informally that an electronic system would likely take years to gain regulatory approval. It wasn't that the CFTC didn't like the idea of electronic trading; on the contrary, they loved it.

The CFTC staff knew that screen-based trading would allow them to know precisely when each trade was entered, received, and executed. They would be better able to see whether, for example, a broker was trading ahead of his customer. 3 It was very difficult to pin down the precise time that a pit trade occurred, since execution consists of a shout and a reply and the only record of the time of execution was the time the floor broker or trader wrote down on an order or trading card. Often the floor guys would execute a number of trades and then, when they had a second to do so, write them down, guessing a little at the precise time each trade took place. In a very busy market, considerable time could elapse between actual execution and the time at which the trade was written down. All this makes it very difficult for either the exchange or the regulator to know whether a broker traded ahead of his customer in a floor-based system. According to someone involved with INTEX at the time, the reason that the CFTC informally advised Grummer and Peak to go offshore was because the big floor-based exchanges in Chicago and New York would do everything they could to slow down the approval and the process would probably take years instead of months.

So, to get up and running more quickly, the INTEX leaders decided to establish the new exchange in Bermuda. Why Bermuda? INTEX had chosen the London Commodity Clearing House (LCCH) to clear the Exchange's trades, and LCCH already had a presence in Bermuda, so it would be relatively quick to get permission to both establish the Exchange and import the state-of-the-art computer equipment into the country. What was state of the art at the beginning of the PC revolution was Tandem computer equipment placed in Bermuda at the INTEX offices and then hardwired via transatlantic cable to DEC 10 computers at member desks in the United States.

Those who wanted to join INTEX had to pay about $36,000—$20,000 for the membership and another $16,000 for the computer. INTEX had 600 memberships available, and by the Fall 1984 launch date, some 285 of the 600 had been sold.

The launch date had been announced and missed a number of times during the period of INTEX's gestation. One participant recalls at least four official launch dates. The problem was the old one of “the perfect being the enemy of the good.” The exchange tried to incorporate all the suggestions given by potential participants. During the planning process there had been discussions of listing both gold and U.S. Treasury bonds (T-bonds) on day one, but the Exchange finally decided to put only one egg in the opening basket, and that egg was gold. The idea was to later add T-bonds, freight rate futures, and possibly silver to the contracts available for trading.

So finally, on October 25, 1984, INTEX successfully opened its electronic doors. Opening day was disappointing. The world's first electronic futures exchange saw only 142 gold contracts traded in an abbreviated four-hour session. 4 And things never got much better. INTEX was a failure.

Why did INTEX fail? It was partly the choice of contract. The conventional wisdom is that new contracts have the greatest chance of success in a bull market. They generate more of a buzz and more speculative interest. By the time INTEX launched gold in October 1984, the metal was in anything but a bull market. Gold, with a few reversals, had been in a long bear market since its $850 peak in January 1980 and was just under $340 that Thursday morning in October when INTEX opened its doors. The fact that it was headed down below $290 by March didn't help things.

Even more important, there were strong forces at work to ensure that INTEX would fail, no matter what product it chose. All the floor-based exchanges in Chicago and New York saw INTEX as a threat to their way of life. The several thousand individual members of the CME, CBOT, and COMEX knew how to make a living in a floor-based world. They did not want their exchanges to go electronic, and their elected leaders who ran the exchanges did what they could to maintain the status quo. So, when the big exchanges were given an opportunity to participate in INTEX, they all declined. But they went even further: They made it clear to the brokerage firms that they'd better not support INTEX either. If they did, things could get nasty. We don't know whether any threats were carried out, but we do know that firms were threatened with the loss of prime booth space on the trading floor (that is, near the pit) if they threw any business to INTEX.

So, what happened to INTEX? Four and a half years after the abortive launch of the INTEX exchange, the parent, INTEX Holdings, joined with Telerate, a supplier of financial data, to create an electronic trading system for the London International Financial Futures Exchange (LIFFE). 5 This screen-based system was called APT (for Automated Pit Trading) and became an after-hours electronic system, similar to GLOBEX at the CME, Project A at the CBOT, and Access at NYMEX.

So the first attempt at screen-traded derivatives failed. We now turn to the second attempt, which started in a rather surprising place and which, unlike INTEX, was at least a modest success.

New Zealand and the Wool Guys6

It's clear why the first automated exchange was set up in Bermuda: because it would have taken forever to get approval in the United States. It was really a U.S. exchange run by U.S. citizens largely directed to U.S. customers but set up in a place where regulatory approval was possible. But why was the second one set up in New Zealand? The entire country of New Zealand has a population about half the size of Chicago. It has never been considered to be on the frontier of technology. But little New Zealand was absolutely a pioneer in the development of screen-based trading. It's almost like no one ever told them they couldn't do it.

It all started with seven wool traders who were spread around four wool-trading centers: Auckland, Wellington, Christchurch, and Napier. They had traded with each other over the telephone and had traded wool futures on the London Wool Terminal Market, a futures market for Australian and New Zealand wool. They decided it was time to set up a local futures market in New Zealand, a market that would reflect local New Zealand prices. But there was a problem: Because they were scattered around the country, they could not all be present for trading on a physical floor in any one of the four wool centers. So they decided that the exchange needed to be computerized.

First, they needed to join forces with some deeper pockets, so they enlisted the support of 10 financial institutions. Together the wool traders and financial institutions would own the exchange. Second, they established a relationship with the International Commodity Clearing House (ICCH), a subsidiary of the London Commodity Clearing House. ICCH became the new exchange's clearinghouse, but just as important, it helped them develop the new automated trading system, cleverly called ATS for, yes, automated trading system.

So, on January 20, 1985, the New Zealand Futures Exchange opened its computer screens for trading in three financial contracts: prime commercial paper, 5-year government bonds, and U.S. dollar/New Zealand dollar. The 10 financial institutions wanted to lead off with the financial products. Wool was added a few months later. Volumes were small; 200 contracts was a big trading day. However, due to the 1990 Gulf War, volumes picked up and the system slowed down. So, the system was modified to handle more volume and, more important, to accommodate the individual share options added in 1990. The exchange also added two more words to its name, becoming the New Zealand Futures and Options Exchange (NZFOE). The name no longer exists, since the 17 owners sold the exchange to the Sydney Futures Exchange (SFE) in 1991, which was merged with the Australian Stock Exchange in 2006. The SFE, incidentally, had developed its own electronic system, called SYCOM, which was created not as the primary trade matching system but only as a venue for trading once the pits had closed for the day.

So there are two answers to the question of why New Zealand was the number-two fully automated derivatives exchange in the world. First is that screens solved the logistical problem of traders spread around the country, and second, the exchange was brand new, so there was no painful transition from a floor.

The first electronic exchange, INTEX, failed. The second electronic exchange, NZFOE, survived. But we have to get to number three before we begin to see really spectacular success.

OM: The First Successful Screen-Based Exchange

OM, the abbreviation for a Swedish word7 meaning options market, was founded by Olof Stenhammer in 1985, making it the third electronic exchange in the world, after INTEX and New Zealand, and the first really successful one. Though Stenhammer had an early encounter with options as a New Jersey broker selling options right after the creation of the Chicago Board Options Exchange (CBOE) in the early 1970s, he was mainly an entrepreneur looking for opportunity. When his New Jersey brokerage firm went belly up, he left options for the better part of a decade and returned to Sweden as the CEO of a sporting goods company.

But he couldn't get options out of his head, and he began designing a fully electronic system that would leapfrog the technology of the CBOE, which had in 1984 introduced a system for the automatic execution of small retail orders. 8 A relentless and persuasive marketer, Stenhammer lined up prestigious backers that would immediately put the new Swedish exchange on the map. With the country's largest bank, Enskilda, and its biggest industrial concern, the Wallenberg Group, capitalizing the venture (he kept only 10% of the shares for himself), he began an aggressive campaign, visiting all the institutional investors, banks, and securities firms in the country. 9

OM was a success from the start. In its first year, when it started with options on six Swedish stocks, it actually made a pretax profit of $24.4 million on revenues of $121.8 million. 10 Two years in, its trading volume averaged 30,000 contracts per day. And this was only options on individual shares; index options would come later.

OM would be challenged and tested while still an infant. OM's success and relatively high fees invited competition. A new Swedish options exchange, called SOFE, opened for business in 1987, when OM was only two years old. 11 SOFE was the opposite of OM. It was nonprofit and floor-based, adopting the model in use worldwide—a perfect test, two new exchanges, one old style, floor based and not for profit, the other new style electronic and stockholder owned. The president of SOFE was Stefan Ingves, a former professor of economics and vice president of a Swedish bank, who would later become the chairman of the Central Bank of Sweden. But despite his later accomplishments, a professor and the old model pitted against an entrepreneur and the new model was no contest, especially given OM's two-year head start. OM stayed and prospered; SOFE disappeared. The advantages of screen-based trading in terms of transparency and cost are generally so great that we will see the outcomes of similar competitions settled in a similar manner. In a case in the 1990s, when a floor-based London exchange had a significant head start over a screen-based Frankfurt exchange, the screen won hands-down again.

This electronic success of OM was a very different outcome from the failure of the first screen-based exchange, INTEX, which had attempted to compete with some of the biggest and oldest futures exchanges in the world. Next, we turn to one last early and unsuccessful pioneer, which made its try also in 1985 and was a neighbor to the wool guys.

Melbourne Tries Screens12

There is one other exchange that deserves mention simply to set the historical record right. Sometime in 1985, the Stock Exchange of Melbourne (Australia) set up a futures subsidiary to list futures contracts on individual shares of stock. The venture was born out of a healthy rivalry between Melbourne and the Sydney Stock Exchange, which had built up quite a successful business in equity options. Melbourne hoped to match Sydney's successful voyage into equity options by creating successful equity futures business. The new exchange was called the Australian Financial Futures Market (AFFM) and it was totally electronic. Over the next two years AFFM added both a Dow Jones-type index and an index of gold-mining companies. But the exchange never got traction, and by the early 1990s all trading had dried up. Why? Because commissions for futures were lower and the new contracts were cash-settled instead of resulting in a delivery of stock, so brokers viewed them as competitive and potentially eroding their stock commissions, and thus were not anxious to sell them. In addition, a new futures law separated futures from equities and made it more difficult for the floor brokers on the stock exchange to support them. For those reasons, today this early pioneer is more of an historical footnote.

Next we turn to two markets that were absolutely not footnotes. These are the markets of two countries located in the middle of Europe, a tiny one and a huge one, whose exchanges joined forces to create one of the scariest electronic juggernauts ever seen.

SOFFEX: Unexpectedly Electronic

The Swiss Options and Financial Futures Exchange (SOFFEX) wasn't originally planned as an electronic exchange. Otto Nageli, former CEO of the new Swiss derivatives exchange, called it “an accident caused by federalists.”13 When a group was formed in Switzerland in 1982 to discuss the adoption of financial futures and options in the country, the seven Swiss stock exchanges were floor-based, and the idea was to create a floor-based derivatives exchange with trading posts. But there was a slight problem. The three biggest exchanges at Geneva, Zurich, and Basel all wanted these new products to trade on their floors. An initial decision was made to list options at these biggest three. However, as research and discussions continued, it became clear that maintaining floor operations at all three exchanges would be unnecessarily costly. Having the new exchange in cyberspace seemed to solve both the political and cost problems, so, with a financing commitment from the five major Swiss banks, SOFFEX was founded in December 1986.

Even before the new exchange was up and running, SOFFEX's neighbors to the north, the guys who were putting together the new German exchange, suggested an alliance. Deutsche Terminbörse (DTB) was a couple of years behind SOFFEX, but the two exchanges agreed to cooperate, starting with DTB's agreement to license SOFFEX's software.

Between that first planning meeting in 1982 and the official opening of SOFFEX on May 19, 1988, six years passed. The Swiss achievement needs to be appreciated for the fact that though there were several prior attempts to create electronic exchanges, this was the first time that an exchange was being created with an integrated electronic clearing house. The first stage in development was the creation of systems to broadcast price quotes electronically. The second stage involved adding the ability to actually match trades online. This was achieved by OM. The third stage was to integrate the matching engine with the clearing system. SOFFEX was first to do this.

DTB: The Other Half of the World's Biggest Exchange

Deutsche Terminbörse (DTB), an exchange that no longer exists, will always be known for two things. First, it was the first exchange in modern history to steal a liquid, successful market from another exchange (the German Bund from LIFFE). Second, it was half of the 1998 DTB/SOFFEX partnership that became Eurex, the world's dominant derivatives exchange for almost a decade until the 2007 mega-merger of the two giant Chicago derivatives exchanges, the CME and the CBOT. Both of these achievements were the result of screen-based trading.

The idea of a German futures and options exchange came from some visionaries at the German banks—people like Rolf Breuer at Deutsche Bank, who would later rise to become chairman of the bank as well as chairman of Deutsche Boerse AG, the holding company of all the German exchanges. 14 The group of banks recruited Jorg Franke, then general manager of the Berlin Stock Exchange, to set up the new derivatives venture. The Germans had a problem that was similar to that of the Swiss and the wool guys in New Zealand: The banks putting the exchange together were located in Berlin, Hamburg, Stuttgart, Munich, and Hanover, so locating the exchange at any one of the cities would not allow all the rest of them to have convenient access to the trading floor. The only place that would work for all of them was cyberspace.

But to be electronic, the DTB needed a system, and the banks decided that instead of starting from scratch it was better to buy the system from their Swiss neighbors, who were a full two years ahead. They also hired Andersen Consulting to tweak the SOFFEX software so that it met the trading requirements of the German banks. The banks also needed to get the national Stock Exchange Act amended so that futures were no longer considered gambling and the contracts would consequently become legally binding.

By the end of 1989, everything was mostly in place and a start date of January 29, 1990, was announced. The launch date was met, but not without some glitches. One bank was almost not ready, and there were problems with the celebratory video link with the Chicago Mercantile Exchange. But, according to Dr. Franke, the project came in on budget and on time. 15

The first test of the system was in August of that first year with the breakout of the first Gulf War and a big wave of trading volume. DTB was not ready for these events, and for several weeks performance slowed considerably. Of course, there were also complaints, but the capacity problem was soon fixed.

One of the most important things the DTB did to ensure its success was to pursue the establishment of remote memberships in Paris, London, and the United States. First came Paris. In 1993, Jorg Franke of DTB began discussions with Gerard Pfauwadel, CEO of Marché A Terme d’Instruments Financiers (MATIF). Franke felt that only MATIF, among all exchanges, really understood the competitive power of an electronic exchange. 16 The two agreed to make their products available to the members of each other's exchanges via the DTB platform, so that MATIF members would be able to electronically trade DTB products on DTB terminals placed in Paris. MATIF would reciprocate by making their products available on the DTB system for DTB members in Germany and Switzerland. Pfauwadel knew that the big benefit for MATIF was that this deal would fast-track the exchange into electronic trading, moving the French MATIF ahead of the British LIFFE, which still restricted electronic trading to the end of the day after regular pit trading hours on its APT system. To accommodate this product agreement, Franke had agreed to allow the DTB platform to be adapted to support the MATIF products and French trading rules.

The adaptation was completed, and in 1995 the DTB products were made available to MATIF members. Then came the runaway bride; Pfauwadel left Franke standing alone at the altar. What neither he nor Franke anticipated was the pushback by the smaller MATIF members concerned about the cost of going electronic. They voted not to move the French products to the screen. As a result, Pfauwadel lost his job; Franke lost half his bonus, and it was quite an embarrassment—except that the French traders still had their DTB terminals, and many of them began using them to trade and add liquidity to the DTB products.

All through the French courtship, DTB was also working on bringing U.S. customers to its screens. Specifically, within a year of launching the exchange, Franke had asked the U.S. federal regulator for permission to place its terminals in the United States to allow U.S. traders to trade DTB products. The CFTC staff did what most regulators do when faced with a novel request with unknown consequences: They thought about it, discussed it, and then focused their attention on other pressing matters that made more sense. Finally, after five years of discussion, on February 19, 1996, the CFTC granted the DTB the historic first permission for a “foreign board of trade” to place its terminals in the United States. 17 Both the CME and CBOT allowed DTB terminals on the floor for use by exchange members. Then trading from the United States began to further build volumes and liquidity in the German products.

Though all this remote trading was good for DTB business generally, it played a key role in a very important competition in which DTB was engaged. In short, it allowed the DTB to steal LIFFE's number-one contract, German Bund futures, and to increase DTB's volume in possibly the most spectacular manner of any exchange ever. When DTB and its new Bund merged with SOFFEX to create Eurex in Fall 1998, the result was the biggest derivatives exchange in the world. (See the box for details.)

The Event That Struck Fear in the Hearts of Floor-Based Exchanges Worldwide

In 1988 the floor-based British exchange, LIFFE, crossed geographical boundaries and became the first exchange to list futures on the very important German bund. At the time futures contracts were legally considered gambling in Germany, and thus no German futures exchange had been created. By the early 1990s the bund had grown to be LIFFE's biggest product. Of course, the Germans believed that futures on Germany's key long-term government bond rightfully belonged on a German exchange, and DTB listed the product in 1990, its first year of trading. But there is a longstanding principle in futures markets that once significant liquidity is entrenched in a product, it is virtually impossible for another exchange to successfully list that product.

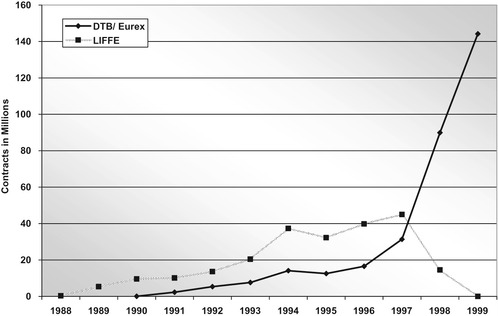

All buyers and sellers want to be where they are most likely to find other buyers and sellers and thus will be able to easily enter and exit the market. For several years, the principle seemed to hold as LIFFE maintained a significant lead. But there was a difference here. Usually a competitor exchange fails to get a foothold and will struggle for a few months or years until its clone of the first exchange's liquid product disappears. In its first year, the DTB traded 5 million bund contracts, and it grew virtually every year following, though LIFFE continued to maintain more than a two-thirds market share (see Figure 2.1).

Then, in 1997 and 1998, it all turned. DTB cut fees and made its terminals available for free to foreign participants, at least for a limited period. It got the crowd's attention. With traders from the United States, London, and Paris focusing their attention on the much cheaper-to-trade and more transparent DTB bund, volume shifted dramatically. In 1997 DTB's bund volume doubled. In 1998 it tripled and grabbed almost 90% of the market. By 1999 it was all over; the LIFFE contract was dead. LIFFE's bund volume fell from 14.5 million contracts in 1998 to zero in 1999. DTB's volume rose from 90 to 144 million over the same two years. It was an astounding reversal of fortune. LIFFE, which had been number one in Europe and number two in the world, had fallen precipitously from its throne. DTB—or, more accurately, the new Eurex, since DTB and SOFFEX merged into Eurex in September 1998—was now the biggest exchange in the world. Thus the awesome power of screen-based trading struck fear in the hearts of all who were not yet on board.

SOFFEX + DTB = Eurex

The two exchanges formed an alliance and combined their technologies, both of which were at the early stages of launching a fully electronic trading platform. Eurex provided members of both marketplaces a joint platform and clearing services for trading. Eurex focused on building technology to support the full trade cycle and a graphical user interface (GUI) that traders could use to trade. In addition, it built an application that the trading firms could use to manage their risk exposure while trading. As an early adopter of technology, Eurex had no choice but to build these applications itself to ensure that a stable and scalable trading platform was available for its users.

Although in its early years Eurex focused on building applications to support various functions of the trade cycle, it did support new entrants in the marketplace. In 1999, Eurex launched the third version of its software, which provided an open interface that allowed vendors and customers to connect directly to Eurex. Since its launch, Eurex has focused on continued improvement in its technology to grow its market base globally. It provides remote access to allow traders around the globe to connect to Eurex. It has worked closely with vendors and customers to ensure a smooth migration toward electronic trading. Furthermore, it helped bring new independent software vendors (ISVs) into the market. These ISVs built trading screens similar to those built by Eurex. The difference, of course, was that the ISVs connected more than just Eurex markets to their screens. As the electronic trading migration grew and as more exchanges were available electronically, the ISVs built exchange gateways through application programming interfaces (APIs) 18 to connect to these markets.

SAFEX: An Electronic Success from an Unexpected Corner of the World19

Some places went electronic just because there was a single entrepreneur who pushed things in that direction. South Africa was one of those places. In January 1985, a bright, driven guy named Russell Loubser and four other guys from a newly constituted Rand Merchant Bank started making a market in bond options. This over-the-counter (OTC) market was the beginning of derivatives markets in South Africa. The market was Nasdaq-like, with prices listed on a screen and deals done via telephone. The big difference was that while Nasdaq had many competing market makers linked together, the new bond options market in South Africa had only one: Rand Merchant Bank. Rand was everyone's counterparty—nice margins, but pretty significant risk for Rand.

Based on the bank's success in bonds, on April 1, 1987, Rand turned its attention to futures on several stock indexes published by the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE). Again Rand was the only market maker. The market-making business was quite profitable, and things were running along nicely until the world market stepped off the cliff known as the crash of October 1987 and the bank got burned badly. 20 Loubser realized that the only way to really grow this market, as well as get out of the job of being South Africa's only market maker, was to get stock index futures listed on a proper futures exchange. So, in August 1990, just seven months following DTB's opening day, the South African Futures Exchange (SAFEX) was created as a screen-based exchange trading many of the same futures that for three years had been traded only OTC.

Loubser became chairman of the new exchange; Stuart Rees became CEO; and a young kid from London named Patrick Birley signed on to do everything else. The exchange grew rapidly during those early years, even though it had fewer than two dozen employees. By 1996, the benchmark All Share Index was trading 1.9 million contracts and the Gold Index another 1.4 million—quite a debut for a tiny exchange in a small, third-world country. A decade later Birley became CEO, and one of his jobs was to assist in the merger of the three South African exchanges (the JSE, SAFEX, and the Bond Market Association) into a single exchange now known as JSE Ltd. Today SAFEX is a division of JSE Ltd., of which Loubser is chairman.

Asian Early Adopters

Japan

The Tokyo Grain Exchange (TGE) was an early innovator, moving its floor system onto screens on April 1, 1988. Though this was almost three years after OM and just a few months before SOFFEX, the TGE has the distinction of being the first floor-based exchange to shift to computer screens. All the exchanges that preceded the TGE into the world of screens—INTEX, New Zealand, OM, and SOFFEX—were new exchanges that were born electronic. The TGE chose to convert from the old method.

Why was the TGE the first exchange to convert from floor to screen? For one thing, it was easier to convert the traditional Japanese trading system to screen than it was to convert the traditional Western system. Here's the difference: In the Western continuous double auction, traders can bid and offer, buy and sell, at any time during a four- to seven-hour trading period, and there might be thousands of transactions at hundreds of different prices during the day, with real-time price feeds sending every bid, offer, and transaction out to a waiting public. In the Japanese single-price auction (known as Itayose or session trading), which has been widely used in futures on physical commodities in Japan, there are a small number of trading sessions during the day, in which all interested buyers and sellers are matched at a single price. For example, the Tokyo Grain Exchange has six daily sessions for trading corn futures—9:00, 10:00, and 11:00 a.m. and 1:00, 2:00, and 3:00 p.m. At each of these sessions, the exchange posts a provisional price that it feels represents a balance of potential buy and sell orders. At that price, all members post the number of contracts they and their customers are willing to buy and sell. If there are, for example, more contracts offered for sale than bid on, the provisional price posted is too high and is lowered, and participants again indicate how many contracts they are willing to buy and sell at the new lower price. The process is continued until the number of contracts offered equals the number of contracts bid on. All parties are matched at that price, and the price and quantity transacted for the session are disseminated to the marketplace.

So, beginning on that crisp spring day in Tokyo in 1988, computer terminals were placed directly on the trading floor so that instead of standing and indicating buy and sell orders to exchange representatives via hand signals, the members did the same thing via terminals. As time went on, brokers were allowed to have the terminals in their offices.

Though most Japanese commodities were traded in these single price auctions, in April 1991 the Tokyo Commodities Exchange (TOCOM) converted its precious metals—gold, silver, and platinum—to an electronic version of the continuous double-auction trading system used in the West. This was a more difficult conversion, but technology had advanced by three years since TGE's conversion. Gradually all the Japanese derivatives and securities exchanges converted to an electronic model. The process was completed on September 3, 2007, with the conversion of the final holdout, the Central Commodity Exchange of Japan.

China as an Early Adopter21

Chinese futures markets were introduced in the early 1990s, first at the Zhengzhou Commodity Exchange (an overnight train trip west of Beijing), then followed quickly by exchanges in Shenzhen, Suzhou, Dalian, Shanghai, and many other places; by 1993 there were over 40 exchanges in China. But the amazing thing about this rapid proliferation of exchanges is that in a country of cheap labor, where labor-intensive floor exchanges would, at least superficially, seem to have made more sense, virtually all these exchanges were electronic.

So, how did this happen? Initially, in the first couple years of the decade, the exchanges traded cash and forward products and most activity was on a trading floor. At some exchanges, traders wandered around the floor and struck deals one by one. At others, the exchanges would actually hold auctions at which traders would bid. During this period, Zhengzhou sent its president and chief economist to visit exchanges in Europe, Asia, and North America. They came to the conclusion that open outcry was too open and public in that it didn't allow for sufficient anonymity for traders and that the screen system was more orderly. They also figured it was easier to find people who could program than to find people who understood how to make markets on a trading floor. They came back to China and developed a simple electronic trading system for standardized futures, and on May 23, 1993, the Zhengzhou Commodity Exchange, the first true futures exchange in China, traded its first futures contract on a screen. The rest of the exchanges quickly followed suit.

The exception was the Shenzhen Metals Exchange, which created a London Metals Exchange-style trading floor. But it quickly found itself bogged down in errors, misunderstandings, disputes, and defaults, and it too switched to a screen-based system. It concluded that floor-based trading was actually more expensive once you factored in all the problems. For both Shenzhen and all the other exchanges, they were started by and owned by the government in some form, often a municipal government. Even though the initial startup costs were greater for electronic trading, government entities didn't mind and were willing to front the money for these projects. Electronic trading, as even the regulators of the U.S. exchanges knew, was easier to monitor and regulate and would help prevent the cheating of customers.

The Chinese exchanges were electronic, with a twist. All the terminals were located on a trading floor, arranged in circles or in a big U or in two big blocks facing one another, depending on the shape of the trading floor. In a sense it was a hybrid system. Like the exchanges in Chicago, the traders came down to the floor to trade every day. But they sat at terminals on the floor rather than standing in pits waving their hands and yelling out what they wanted to do. In fact, they are still referred to as pit traders. Some, called self-trading members, trade their own accounts, but the majority, called agent-trading members, trade for clients. Order entry and matching are electronic, but entry is handled by these agent-trading members who receive orders over the phone or by fax or email. With all traders sitting in one room, they could get up and wander over to the desks of other traders to discuss a trade, a technical issue, or the latest joke. The arrangement preserved some of the social aspects of the floor. It also had everyone in one room, where they could be more easily monitored by exchange authorities. But the biggest driver for this setup was technical: in the early 1990s in China, it was much easier to connect a trade-matching system to a bunch of computers in one room than to computers spread throughout a building, a city, or a country. The Internet had not really come to China yet.

Both the exchange and the government liked having all the traders in a single room. Since futures—and for that matter, markets generally—were new to China, the exchanges wanted something visual that they could show visitors. This was especially true for potential customers such as grain merchants and others involved in the cash commodity markets. And, since government support was crucial for these new creations, a floor made it much easier to explain to government officials what was going on. Trading floors have always been more interesting than PowerPoint slides. Of course, the government liked having all the traders in one place so it could keep an eye on them. Finally, for purposes of general promotion, there is nothing like a trading floor for the media to take photos of and for the general public to visit, just as they would the Forbidden City, the Great Wall, or the Shaolin Temple.

That was in the beginning. Today upstairs brokers have direct access to the exchange and no longer need to go through the guys on the floor. The floor terminals at China's three existing exchanges have practically all been idled. About 70% of the orders are entered through terminals off the floor, though it is still used as a convenient, though less active, visual representation of the trading process for visitors from all over.

Conclusion

The electronic pioneers were a group of people who saw the world not just as it was but as it could be—in fact, as it should be. Sometimes the screen-based system solved the political problem of which city in a country got to have the exchange, as was the case in New Zealand and Switzerland. But more often it was simply viewed as a faster, cheaper, more transparent way to trade. For those who appreciated the opportunities created by the advance of technology, it was viewed as inevitable. As we’ve seen, most of the pioneers were setting up new exchanges. It was much easier to adopt this technology in a brand-new business than to radically transform an existing exchange, especially when the member-owners got to vote on whether to stick with the floors they knew or to jump into a world of screens they knew little about.

In the next chapter we examine the second phase of the adoption of electronic trading, where the older floor-based exchanges began to transform themselves.

Endnotes

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8. In 1984, the CBOE introduced its Retail Automatic Execution System (RAES) for the electronic matching of small retail orders of 10 contracts or fewer in the most active options. CBOE History at; www.cboe.com/AboutCBOE/History.aspx.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.