2

Enhancing Your Blog with Advanced Features

In the preceding chapter, we learned the main components of Django by developing a simple blog application. We created a simple blog application using views, templates, and URLs. In this chapter, we will extend the functionalities of the blog application with features that can be found in many blogging platforms nowadays. In this chapter, you will learn the following topics:

- Using canonical URLs for models

- Creating SEO-friendly URLs for posts

- Adding pagination to the post list view

- Building class-based views

- Sending emails with Django

- Using Django forms to share posts via email

- Adding comments to posts using forms from models

The source code for this chapter can be found at https://github.com/PacktPublishing/Django-4-by-example/tree/main/Chapter02.

All Python packages used in this chapter are included in the requirements.txt file in the source code for the chapter. You can follow the instructions to install each Python package in the following sections, or you can install all the requirements at once with the command pip install -r requirements.txt.

Using canonical URLs for models

A website might have different pages that display the same content. In our application, the initial part of the content for each post is displayed both on the post list page and the post detail page. A canonical URL is the preferred URL for a resource. You can think of it as the URL of the most representative page for specific content. There might be different pages on your site that display posts, but there is a single URL that you use as the main URL for a post. Canonical URLs allow you to specify the URL for the master copy of a page. Django allows you to implement the get_absolute_url() method in your models to return the canonical URL for the object.

We will use the post_detail URL defined in the URL patterns of the application to build the canonical URL for Post objects. Django provides different URL resolver functions that allow you to build URLs dynamically using their name and any required parameters. We will use the reverse() utility function of the django.urls module.

Edit the models.py file of the blog application to import the reverse() function and add the get_absolute_url() method to the Post model as follows. New code is highlighted in bold:

from django.db import models

from django.utils import timezone

from django.contrib.auth.models import User

from django.urls import reverse

class PublishedManager(models.Manager):

def get_queryset(self):

return super().get_queryset()

.filter(status=Post.Status.PUBLISHED)

class Post(models.Model):

class Status(models.TextChoices):

DRAFT = 'DF', 'Draft'

PUBLISHED = 'PB', 'Published'

title = models.CharField(max_length=250)

slug = models.SlugField(max_length=250)

author = models.ForeignKey(User,

on_delete=models.CASCADE,

related_name='blog_posts')

body = models.TextField()

publish = models.DateTimeField(default=timezone.now)

created = models.DateTimeField(auto_now_add=True)

updated = models.DateTimeField(auto_now=True)

status = models.CharField(max_length=2,

choices=Status.choices,

default=Status.DRAFT)

class Meta:

ordering = ['-publish']

indexes = [

models.Index(fields=['-publish']),

]

def __str__(self):

return self.title

def get_absolute_url(self):

return reverse('blog:post_detail',

args=[self.id])

The reverse() function will build the URL dynamically using the URL name defined in the URL patterns. We have used the blog namespace followed by a colon and the URL name post_detail. Remember that the blog namespace is defined in the main urls.py file of the project when including the URL patterns from blog.urls. The post_detail URL is defined in the urls.py file of the blog application. The resulting string, blog:post_detail, can be used globally in your project to refer to the post detail URL. This URL has a required parameter that is the id of the blog post to retrieve. We have included the id of the Post object as a positional argument by using args=[self.id].

You can learn more about the URL’s utility functions at https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/4.1/ref/urlresolvers/.

Let’s replace the post detail URLs in the templates with the new get_absolute_url() method.

Edit the blog/post/list.html file and replace the line:

<a href="{% url 'blog:post_detail' post.id %}">

With the line:

<a href="{{ post.get_absolute_url }}">

The blog/post/list.html file should now look as follows:

{% extends "blog/base.html" %}

{% block title %}My Blog{% endblock %}

{% block content %}

<h1>My Blog</h1>

{% for post in posts %}

<h2>

<a href="{{ post.get_absolute_url }}">

{{ post.title }}

</a>

</h2>

<p class="date">

Published {{ post.publish }} by {{ post.author }}

</p>

{{ post.body|truncatewords:30|linebreaks }}

{% endfor %}

{% endblock %}

Open the shell prompt and execute the following command to start the development server:

python manage.py runserver

Open http://127.0.0.1:8000/blog/ in your browser. Links to individual blog posts should still work. Django is now building them using the get_absolute_url() method of the Post model.

Creating SEO-friendly URLs for posts

The canonical URL for a blog post detail view currently looks like /blog/1/. We will change the URL pattern to create SEO-friendly URLs for posts. We will be using both the publish date and slug values to build the URLs for single posts. By combining dates, we will make a post detail URL to look like /blog/2022/1/1/who-was-django-reinhardt/. We will provide search engines with friendly URLs to index, containing both the title and date of the post.

To retrieve single posts with the combination of publication date and slug, we need to ensure that no post can be stored in the database with the same slug and publish date as an existing post. We will prevent the Post model from storing duplicated posts by defining slugs to be unique for the publication date of the post.

Edit the models.py file and add the following unique_for_date parameter to the slug field of the Post model:

class Post(models.Model):

# ...

slug = models.SlugField(max_length=250,

unique_for_date='publish')

# ...

By using unique_for_date, the slug field is now required to be unique for the date stored in the publish field. Note that the publish field is an instance of DateTimeField, but the check for unique values will be done only against the date (not the time). Django will prevent from saving a new post with the same slug as an existing post for a given publication date. We have now ensured that slugs are unique for the publication date, so we can now retrieve single posts by the publish and slug fields.

We have changed our models, so let’s create migrations. Note that unique_for_date is not enforced at the database level, so no database migration is required. However, Django uses migrations to keep track of all model changes. We will create a migration just to keep migrations aligned with the current state of the model.

Run the following command in the shell prompt:

python manage.py makemigrations blog

You should get the following output:

Migrations for 'blog':

blog/migrations/0002_alter_post_slug.py

- Alter field slug on post

Django just created the 0002_alter_post_slug.py file inside the migrations directory of the blog application.

Execute the following command in the shell prompt to apply existing migrations:

python manage.py migrate

You will get an output that ends with the following line:

Applying blog.0002_alter_post_slug... OK

Django will consider that all migrations have been applied and the models are in sync. No action will be done in the database because unique_for_date is not enforced at the database level.

Modifying the URL patterns

Let’s modify the URL patterns to use the publication date and slug for the post detail URL.

Edit the urls.py file of the blog application and replace the line:

path('<int:id>/', views.post_detail, name='post_detail'),

With the lines:

path('<int:year>/<int:month>/<int:day>/<slug:post>/',

views.post_detail,

name='post_detail'),

The urls.py file should now look like this:

from django.urls import path

from . import views

app_name = 'blog'

urlpatterns = [

# Post views

path('', views.post_list, name='post_list'),

path('<int:year>/<int:month>/<int:day>/<slug:post>/',

views.post_detail,

name='post_detail'),

]

The URL pattern for the post_detail view takes the following arguments:

year: Requires an integermonth: Requires an integerday: Requires an integerpost: Requires a slug (a string that contains only letters, numbers, underscores, or hyphens)

The int path converter is used for the year, month, and day parameters, whereas the slug path converter is used for the post parameter. You learned about path converters in the previous chapter. You can see all path converters provided by Django at https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/4.1/topics/http/urls/#path-converters.

Modifying the views

Now we have to change the parameters of the post_detail view to match the new URL parameters and use them to retrieve the corresponding Post object.

Edit the views.py file and edit the post_detail view like this:

def post_detail(request, year, month, day, post):

post = get_object_or_404(Post,

status=Post.Status.PUBLISHED,

slug=post,

publish__year=year,

publish__month=month,

publish__day=day)

return render(request,

'blog/post/detail.html',

{'post': post})

We have modified the post_detail view to take the year, month, day, and post arguments and retrieve a published post with the given slug and publication date. By adding unique_for_date='publish' to the slug field of the Post model before, we ensured that there will be only one post with a slug for a given date. Thus, you can retrieve single posts using the date and slug.

Modifying the canonical URL for posts

We also have to modify the parameters of the canonical URL for blog posts to match the new URL parameters.

Edit the models.py file of the blog application and edit the get_absolute_url() method as follows:

class Post(models.Model):

# ...

def get_absolute_url(self):

return reverse('blog:post_detail',

args=[self.publish.year,

self.publish.month,

self.publish.day,

self.slug])

Start the development server by typing the following command in the shell prompt:

python manage.py runserver

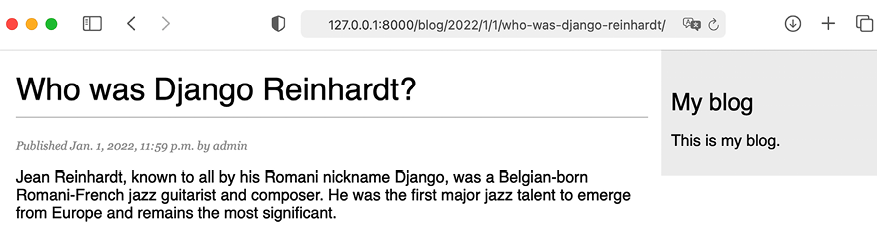

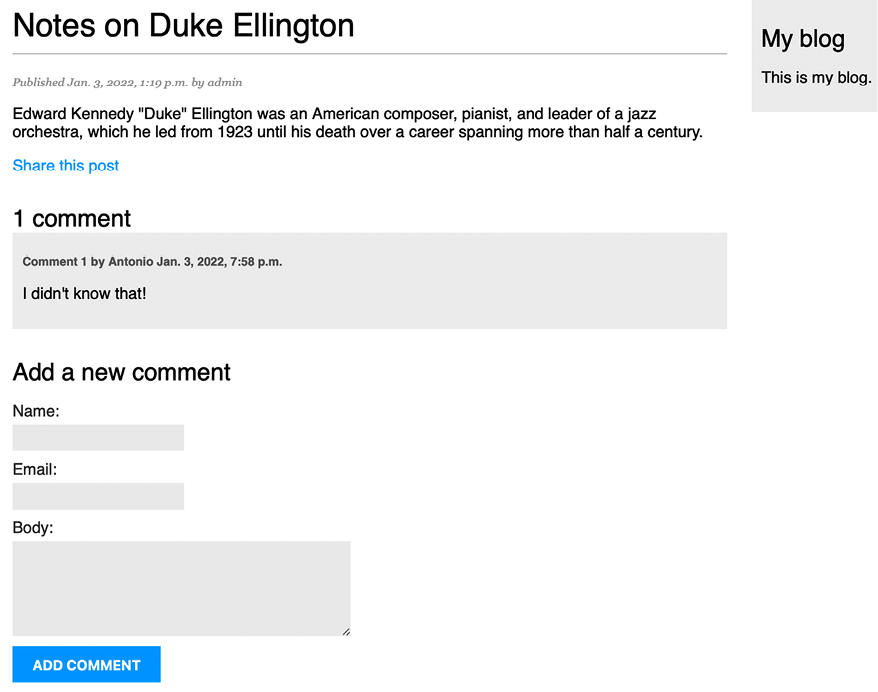

Next, you can return to your browser and click on one of the post titles to take a look at the detail view of the post. You should see something like this:

Figure 2.1: The page for the post’s detail view

Take a look at the URL—it should look like /blog/2022/1/1/who-was-django-reinhardt/. You have designed SEO-friendly URLs for the blog posts.

Adding pagination

When you start adding content to your blog, you can easily store tens or hundreds of posts in your database. Instead of displaying all the posts on a single page, you may want to split the list of posts across several pages and include navigation links to the different pages. This functionality is called pagination, and you can find it in almost every web application that displays long lists of items.

For example, Google uses pagination to divide search results across multiple pages. Figure 2.2 shows Google’s pagination links for search result pages:

Figure 2.2: Google pagination links for search result pages

Django has a built-in pagination class that allows you to manage paginated data easily. You can define the number of objects you want to be returned per page and you can retrieve the posts that correspond to the page requested by the user.

Adding pagination to the post list view

Edit the views.py file of the blog application to import the Django Paginator class and modify the post_list view as follows:

from django.shortcuts import render, get_object_or_404

from .models import Post

from django.core.paginator import Paginator

def post_list(request):

post_list = Post.published.all()

# Pagination with 3 posts per page

paginator = Paginator(post_list, 3)

page_number = request.GET.get('page', 1)

posts = paginator.page(page_number)

return render(request,

'blog/post/list.html',

{'posts': posts})

Let’s review the new code we have added to the view:

- We instantiate the

Paginatorclass with the number of objects to return per page. We will display three posts per page. - We retrieve the

pageGETHTTP parameter and store it in thepage_numbervariable. This parameter contains the requested page number. If thepageparameter is not in theGETparameters of the request, we use the default value1to load the first page of results. - We obtain the objects for the desired page by calling the

page()method ofPaginator. This method returns aPageobject that we store in thepostsvariable. - We pass the page number and the

postsobject to the template.

Creating a pagination template

We need to create a page navigation for users to browse through the different pages. We will create a template to display the pagination links. We will make it generic so that we can reuse the template for any object pagination on our website.

In the templates/ directory, create a new file and name it pagination.html. Add the following HTML code to the file:

<div class="pagination">

<span class="step-links">

{% if page.has_previous %}

<a href="?page={{ page.previous_page_number }}">Previous</a>

{% endif %}

<span class="current">

Page {{ page.number }} of {{ page.paginator.num_pages }}.

</span>

{% if page.has_next %}

<a href="?page={{ page.next_page_number }}">Next</a>

{% endif %}

</span>

</div>

This is the generic pagination template. The template expects to have a Page object in the context to render the previous and next links, and to display the current page and total pages of results.

Let’s return to the blog/post/list.html template and include the pagination.html template at the bottom of the {% content %} block, as follows:

{% extends "blog/base.html" %}

{% block title %}My Blog{% endblock %}

{% block content %}

<h1>My Blog</h1>

{% for post in posts %}

<h2>

<a href="{{ post.get_absolute_url }}">

{{ post.title }}

</a>

</h2>

<p class="date">

Published {{ post.publish }} by {{ post.author }}

</p>

{{ post.body|truncatewords:30|linebreaks }}

{% endfor %}

{% include "pagination.html" with page=posts %}

{% endblock %}

The {% include %} template tag loads the given template and renders it using the current template context. We use with to pass additional context variables to the template. The pagination template uses the page variable to render, while the Page object that we pass from our view to the template is called posts. We use with page=posts to pass the variable expected by the pagination template. You can follow this method to use the pagination template for any type of object.

Start the development server by typing the following command in the shell prompt:

python manage.py runserver

Open http://127.0.0.1:8000/admin/blog/post/ in your browser and use the administration site to create a total of four different posts. Make sure to set the status to Published for all of them.

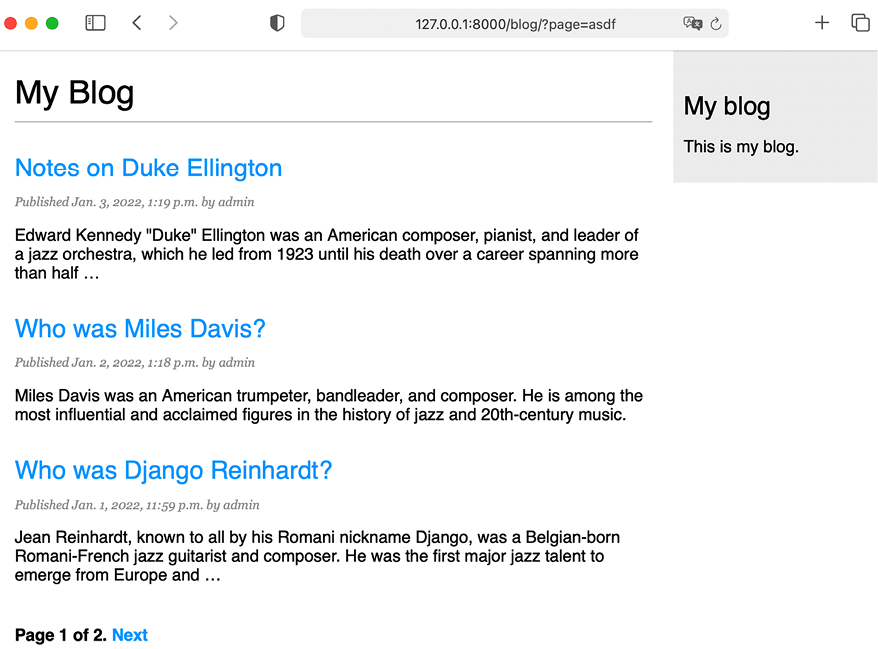

Now, open http://127.0.0.1:8000/blog/ in your browser. You should see the first three posts in reverse chronological order, and then the navigation links at the bottom of the post list like this:

Figure 2.3: The post list page including pagination

If you click on Next, you will see the last post. The URL for the second page contains the ?page=2 GET parameter. This parameter is used by the view to load the requested page of results using the paginator.

Figure 2.4: The second page of results

Great! The pagination links are working as expected.

Handling pagination errors

Now that the pagination is working, we can add exception handling for pagination errors in the view. The page parameter used by the view to retrieve the given page could potentially be used with wrong values, such as non-existing page numbers or a string value that cannot be used as a page number. We will implement appropriate error handling for those cases.

Open http://127.0.0.1:8000/blog/?page=3 in your browser. You should see the following error page:

Figure 2.5: The EmptyPage error page

The Paginator object throws an EmptyPage exception when retrieving page 3 because it’s out of range. There are no results to display. Let’s handle this error in our view.

Edit the views.py file of the blog application to add the necessary imports and modify the post_list view as follows:

from django.shortcuts import render, get_object_or_404

from .models import Post

from django.core.paginator import Paginator, EmptyPage

def post_list(request):

post_list = Post.published.all()

# Pagination with 3 posts per page

paginator = Paginator(post_list, 3)

page_number = request.GET.get('page', 1)

try:

posts = paginator.page(page_number)

except EmptyPage:

# If page_number is out of range deliver last page of results

posts = paginator.page(paginator.num_pages)

return render(request,

'blog/post/list.html',

{'posts': posts})

We have added a try and except block to manage the EmptyPage exception when retrieving a page. If the page requested is out of range, we return the last page of results. We get the total number of pages with paginator.num_pages. The total number of pages is the same as the last page number.

Open http://127.0.0.1:8000/blog/?page=3 in your browser again. Now, the exception is managed by the view and the last page of results is returned as follows:

Figure 2.6: The last page of results

Our view should also handle the case when something different than an integer is passed in the page parameter.

Open http://127.0.0.1:8000/blog/?page=asdf in your browser. You should see the following error page:

Figure 2.7: The PageNotAnInteger error page

In this case, the Paginator object throws a PageNotAnInteger exception when retrieving the page asdf because page numbers can only be an integer. Let’s handle this error in our view.

Edit the views.py file of the blog application to add the necessary imports and modify the post_list view as follows:

from django.shortcuts import render, get_object_or_404

from .models import Post

from django.core.paginator import Paginator, EmptyPage,

PageNotAnInteger

def post_list(request):

post_list = Post.published.all()

# Pagination with 3 posts per page

paginator = Paginator(post_list, 3)

page_number = request.GET.get('page')

try:

posts = paginator.page(page_number)

except PageNotAnInteger:

# If page_number is not an integer deliver the first page

posts = paginator.page(1)

except EmptyPage:

# If page_number is out of range deliver last page of results

posts = paginator.page(paginator.num_pages)

return render(request,

'blog/post/list.html',

{'posts': posts})

We have added a new except block to manage the PageNotAnInteger exception when retrieving a page. If the page requested is not an integer, we return the first page of results.

Open http://127.0.0.1:8000/blog/?page=asdf in your browser again. Now the exception is managed by the view and the first page of results is returned as follows:

Figure 2.8: The first page of results

The pagination for blog posts is now fully implemented.

You can learn more about the Paginator class at https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/4.1/ref/paginator/.

Building class-based views

We have built the blog application using function-based views. Function-based views are simple and powerful, but Django also allows you to build views using classes.

Class-based views are an alternative way to implement views as Python objects instead of functions. Since a view is a function that takes a web request and returns a web response, you can also define your views as class methods. Django provides base view classes that you can use to implement your own views. All of them inherit from the View class, which handles HTTP method dispatching and other common functionalities.

Why use class-based views

Class-based views offer some advantages over function-based views that are useful for specific use cases. Class-based views allow you to:

- Organize code related to HTTP methods, such as

GET,POST, orPUT, in separate methods, instead of using conditional branching - Use multiple inheritance to create reusable view classes (also known as mixins)

Using a class-based view to list posts

To understand how to write class-based views, we will create a new class-based view that is equivalent to the post_list view. We will create a class that will inherit from the generic ListView view offered by Django. ListView allows you to list any type of object.

Edit the views.py file of the blog application and add the following code to it:

from django.views.generic import ListView

class PostListView(ListView):

"""

Alternative post list view

"""

queryset = Post.published.all()

context_object_name = 'posts'

paginate_by = 3

template_name = 'blog/post/list.html'

The PostListView view is analogous to the post_list view we built previously. We have implemented a class-based view that inherits from the ListView class. We have defined a view with the following attributes:

- We use

querysetto use a custom QuerySet instead of retrieving all objects. Instead of defining aquerysetattribute, we could have specifiedmodel = Postand Django would have built the genericPost.objects.all()QuerySet for us. - We use the context variable

postsfor the query results. The default variable isobject_listif you don’t specify anycontext_object_name. - We define the pagination of results with

paginate_by, returning three objects per page. - We use a custom template to render the page with

template_name. If you don’t set a default template,ListViewwill useblog/post_list.htmlby default.

Now, edit the urls.py file of the blog application, comment the preceding post_list URL pattern, and add a new URL pattern using the PostListView class, as follows:

urlpatterns = [

# Post views

# path('', views.post_list, name='post_list'),

path('', views.PostListView.as_view(), name='post_list'),

path('<int:year>/<int:month>/<int:day>/<slug:post>/',

views.post_detail,

name='post_detail'),

]

In order to keep pagination working, we have to use the right page object that is passed to the template. Django’s ListView generic view passes the page requested in a variable called page_obj. We have to edit the post/list.html template accordingly to include the paginator using the right variable, as follows:

{% extends "blog/base.html" %}

{% block title %}My Blog{% endblock %}

{% block content %}

<h1>My Blog</h1>

{% for post in posts %}

<h2>

<a href="{{ post.get_absolute_url }}">

{{ post.title }}

</a>

</h2>

<p class="date">

Published {{ post.publish }} by {{ post.author }}

</p>

{{ post.body|truncatewords:30|linebreaks }}

{% endfor %}

{% include "pagination.html" with page=page_obj %}

{% endblock %}

Open http://127.0.0.1:8000/blog/ in your browser and verify that the pagination links work as expected. The behavior of the pagination links should be the same as with the previous post_list view.

The exception handling in this case is a bit different. If you try to load a page out of range or pass a non-integer value in the page parameter, the view will return an HTTP response with the status code 404 (page not found) like this:

Figure 2.9: HTTP 404 Page not found response

The exception handling that returns the HTTP 404 status code is provided by the ListView view.

This is a simple example of how to write class-based views. You will learn more about class-based views in Chapter 13, Creating a Content Management System, and successive chapters.

You can read an introduction to class-based views at https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/4.1/topics/class-based-views/intro/.

Recommending posts by email

Now, we will learn how to create forms and how to send emails with Django. We will allow users to share blog posts with others by sending post recommendations via email.

Take a minute to think about how you could use views, URLs, and templates to create this functionality using what you learned in the preceding chapter.

To allow users to share posts via email, we will need to:

- Create a form for users to fill in their name, their email address, the recipient email address, and optional comments

- Create a view in the

views.pyfile that handles the posted data and sends the email - Add a URL pattern for the new view in the

urls.pyfile of the blog application - Create a template to display the form

Creating forms with Django

Let’s start by building the form to share posts. Django has a built-in forms framework that allows you to create forms easily. The forms framework makes it simple to define the fields of the form, specify how they have to be displayed, and indicate how they have to validate input data. The Django forms framework offers a flexible way to render forms in HTML and handle data.

Django comes with two base classes to build forms:

Form: Allows you to build standard forms by defining fields and validations.ModelForm: Allows you to build forms tied to model instances. It provides all the functionalities of the baseFormclass, but form fields can be explicitly declared, or automatically generated, from model fields. The form can be used to create or edit model instances.

First, create a forms.py file inside the directory of your blog application and add the following code to it:

from django import forms

class EmailPostForm(forms.Form):

name = forms.CharField(max_length=25)

email = forms.EmailField()

to = forms.EmailField()

comments = forms.CharField(required=False,

widget=forms.Textarea)

We have defined our first Django form. The EmailPostForm form inherits from the base Form class. We use different field types to validate data accordingly.

Forms can reside anywhere in your Django project. The convention is to place them inside a forms.py file for each application.

The form contains the following fields:

name: An instance ofCharFieldwith a maximum length of25characters. We will use it for the name of the person sending the post.email: An instance ofEmailField. We will use the email of the person sending the post recommendation.to: An instance ofEmailField. We will use the email of the recipient, who will receive the email recommending the post recommendation.comments: An instance ofCharField. We will use it for comments to include in the post recommendation email. We have made this field optional by settingrequiredtoFalse, and we have specified a custom widget to render the field.

Each field type has a default widget that determines how the field is rendered in HTML. The name field is an instance of CharField. This type of field is rendered as an <input type="text"> HTML element. The default widget can be overridden with the widget attribute. In the comments field, we use the Textarea widget to display it as a <textarea> HTML element instead of the default <input> element.

Field validation also depends on the field type. For example, the email and to fields are EmailField fields. Both fields require a valid email address; the field validation will otherwise raise a forms.ValidationError exception and the form will not validate. Other parameters are also taken into account for the form field validation, such as the name field having a maximum length of 25 or the comments field being optional.

These are only some of the field types that Django provides for forms. You can find a list of all field types available at https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/4.1/ref/forms/fields/.

Handling forms in views

We have defined the form to recommend posts via email. Now we need a view to create an instance of the form and handle the form submission.

Edit the views.py file of the blog application and add the following code to it:

from .forms import EmailPostForm

def post_share(request, post_id):

# Retrieve post by id

post = get_object_or_404(Post, id=post_id, status=Post.Status.PUBLISHED)

if request.method == 'POST':

# Form was submitted

form = EmailPostForm(request.POST)

if form.is_valid():

# Form fields passed validation

cd = form.cleaned_data

# ... send email

else:

form = EmailPostForm()

return render(request, 'blog/post/share.html', {'post': post,

'form': form})

We have defined the post_share view that takes the request object and the post_id variable as parameters. We use the get_object_or_404() shortcut to retrieve a published post by its id.

We use the same view both for displaying the initial form and processing the submitted data. The HTTP request method allows us to differentiate whether the form is being submitted. A GET request will indicate that an empty form has to be displayed to the user and a POST request will indicate the form is being submitted. We use request.method == 'POST' to differentiate between the two scenarios.

This is the process to display the form and handle the form submission:

- When the page is loaded for the first time, the view receives a

GETrequest. In this case, a newEmailPostForminstance is created and stored in theformvariable. This form instance will be used to display the empty form in the template:form = EmailPostForm() - When the user fills in the form and submits it via

POST, a form instance is created using the submitted data contained inrequest.POST:if request.method == 'POST': # Form was submitted form = EmailPostForm(request.POST) - After this, the data submitted is validated using the form’s

is_valid()method. This method validates the data introduced in the form and returnsTrueif all fields contain valid data. If any field contains invalid data, thenis_valid()returnsFalse. The list of validation errors can be obtained withform.errors. - If the form is not valid, the form is rendered in the template again, including the data submitted. Validation errors will be displayed in the template.

- If the form is valid, the validated data is retrieved with

form.cleaned_data. This attribute is a dictionary of form fields and their values.

If your form data does not validate, cleaned_data will contain only the valid fields.

We have implemented the view to display the form and handle the form submission. We will now learn how to send emails using Django and then we will add that functionality to the post_share view.

Sending emails with Django

Sending emails with Django is very straightforward. To send emails with Django, you need to have a local Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP) server, or you need to access an external SMTP server, like your email service provider.

The following settings allow you to define the SMTP configuration to send emails with Django:

EMAIL_HOST: The SMTP server host; the default islocalhostEMAIL_PORT: The SMTP port; the default is25EMAIL_HOST_USER: The username for the SMTP serverEMAIL_HOST_PASSWORD: The password for the SMTP serverEMAIL_USE_TLS: Whether to use a Transport Layer Security (TLS) secure connectionEMAIL_USE_SSL: Whether to use an implicit TLS secure connection

For this example, we will use Google’s SMTP server with a standard Gmail account.

If you have a Gmail account, edit the settings.py file of your project and add the following code to it:

# Email server configuration

EMAIL_HOST = 'smtp.gmail.com'

EMAIL_HOST_USER = '[email protected]'

EMAIL_HOST_PASSWORD = ''

EMAIL_PORT = 587

EMAIL_USE_TLS = True

Replace [email protected] with your actual Gmail account. If you don’t have a Gmail account, you can use the SMTP server configuration of your email service provider.

Instead of Gmail, you can also use a professional, scalable email service that allows you to send emails via SMTP using your own domain, such as SendGrid (https://sendgrid.com/) or Amazon Simple Email Service (https://aws.amazon.com/ses/). Both services will require you to verify your domain and sender email accounts and will provide you with SMTP credentials to send emails. The Django applications django-sengrid and django-ses simplify the task of adding SendGrid or Amazon SES to your project. You can find installation instructions for django-sengrid at https://github.com/sklarsa/django-sendgrid-v5, and installation instructions for django-ses at https://github.com/django-ses/django-ses.

If you can’t use an SMTP server, you can tell Django to write emails to the console by adding the following setting to the settings.py file:

EMAIL_BACKEND = 'django.core.mail.backends.console.EmailBackend'

By using this setting, Django will output all emails to the shell instead of sending them. This is very useful for testing your application without an SMTP server.

To complete the Gmail configuration, we need to enter a password for the SMTP server. Since Google uses a two-step verification process and additional security measures, you cannot use your Google account password directly. Instead, Google allows you to create app-specific passwords for your account. An app password is a 16-digit passcode that gives a less secure app or device permission to access your Google account.

Open https://myaccount.google.com/ in your browser. On the left menu, click on Security. You will see the following screen:

Figure 2.10: The Signing in to Google page for Google accounts

Under the Signing in to Google block, click on App passwords. If you cannot see App passwords, it might be that 2-step verification is not set for your account, your account is an organization account instead of a standard Gmail account, or you turned on Google’s advanced protection. Make sure to use a standard Gmail account and to activate 2-step verification for your Google account. You can find more information at https://support.google.com/accounts/answer/185833.

When you click on App passwords, you will see the following screen:

Figure 2.11: Form to generate a new Google app password

In the Select app dropdown, select Other.

Then, enter the name Blog and click the GENERATE button, as follows:

Figure 2.12: Form to generate a new Google app password

A new password will be generated and displayed to you like this:

Figure 2.13: Generated Google app password

Copy the generated app password.

Edit the settings.py file of your project and add the app password to the EMAIL_HOST_PASSWORD setting, as follows:

# Email server configuration

EMAIL_HOST = 'smtp.gmail.com'

EMAIL_HOST_USER = '[email protected]'

EMAIL_HOST_PASSWORD = 'xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx'

EMAIL_PORT = 587

EMAIL_USE_TLS = True

Open the Python shell by running the following command in the system shell prompt:

python manage.py shell

Execute the following code in the Python shell:

>>> from django.core.mail import send_mail

>>> send_mail('Django mail',

... 'This e-mail was sent with Django.',

... '[email protected]',

... ['[email protected]'],

... fail_silently=False)

The send_mail() function takes the subject, message, sender, and list of recipients as required arguments. By setting the optional argument fail_silently=False, we are telling it to raise an exception if the email cannot be sent. If the output you see is 1, then your email was successfully sent.

Check your inbox. You should have received the email:

Figure 2.14: Test email sent displayed in Gmail

You just sent your first email with Django! You can find more information about sending emails with Django at https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/4.1/topics/email/.

Let’s add this functionality to the post_share view.

Sending emails in views

Edit the post_share view in the views.py file of the blog application, as follows:

from django.core.mail import send_mail

def post_share(request, post_id):

# Retrieve post by id

post = get_object_or_404(Post, id=post_id, status=Post.Status.PUBLISHED)

sent = False

if request.method == 'POST':

# Form was submitted

form = EmailPostForm(request.POST)

if form.is_valid():

# Form fields passed validation

cd = form.cleaned_data

post_url = request.build_absolute_uri(

post.get_absolute_url())

subject = f"{cd['name']} recommends you read "

f"{post.title}"

message = f"Read {post.title} at {post_url}

"

f"{cd['name']}'s comments: {cd['comments']}"

send_mail(subject, message, '[email protected]',

[cd['to']])

sent = True

else:

form = EmailPostForm()

return render(request, 'blog/post/share.html', {'post': post,

'form': form,

'sent': sent})

Replace [email protected] with your real email account if you are using an SMTP server instead of console.EmailBackend.

In the preceding code, we have declared a sent variable with the initial value True. We set this variable to True after the email is sent. We will use the sent variable later in the template to display a success message when the form is successfully submitted.

Since we have to include a link to the post in the email, we retrieve the absolute path of the post using its get_absolute_url() method. We use this path as an input for request.build_absolute_uri() to build a complete URL, including the HTTP schema and hostname.

We create the subject and the message body of the email using the cleaned data of the validated form. Finally, we send the email to the email address contained in the to field of the form.

Now that the view is complete, we have to add a new URL pattern for it.

Open the urls.py file of your blog application and add the post_share URL pattern, as follows:

from django.urls import path

from . import views

app_name = 'blog'

urlpatterns = [

# Post views

# path('', views.post_list, name='post_list'),

path('', views.PostListView.as_view(), name='post_list'),

path('<int:year>/<int:month>/<int:day>/<slug:post>/',

views.post_detail,

name='post_detail'),

path('<int:post_id>/share/',

views.post_share, name='post_share'),

]

Rendering forms in templates

After creating the form, programming the view, and adding the URL pattern, the only thing missing is the template for the view.

Create a new file in the blog/templates/blog/post/ directory and name it share.html.

Add the following code to the new share.html template:

{% extends "blog/base.html" %}

{% block title %}Share a post{% endblock %}

{% block content %}

{% if sent %}

<h1>E-mail successfully sent</h1>

<p>

"{{ post.title }}" was successfully sent to {{ form.cleaned_data.to }}.

</p>

{% else %}

<h1>Share "{{ post.title }}" by e-mail</h1>

<form method="post">

{{ form.as_p }}

{% csrf_token %}

<input type="submit" value="Send e-mail">

</form>

{% endif %}

{% endblock %}

This is the template that is used to both display the form to share a post via email, and to display a success message when the email has been sent. We differentiate between both cases with {% if sent %}.

To display the form, we have defined an HTML form element, indicating that it has to be submitted by the POST method:

<form method="post">

We have included the form instance with {{ form.as_p }}. We tell Django to render the form fields using HTML paragraph <p> elements by using the as_p method. We could also render the form as an unordered list with as_ul or as an HTML table with as_table. Another option is to render each field by iterating through the form fields, as in the following example:

{% for field in form %}

<div>

{{ field.errors }}

{{ field.label_tag }} {{ field }}

</div>

{% endfor %}

We have added a {% csrf_token %} template tag. This tag introduces a hidden field with an autogenerated token to avoid cross-site request forgery (CSRF) attacks. These attacks consist of a malicious website or program performing an unwanted action for a user on the site. You can find more information about CSRF at https://owasp.org/www-community/attacks/csrf.

The {% csrf_token %} template tag generates a hidden field that is rendered like this:

<input type='hidden' name='csrfmiddlewaretoken' value='26JjKo2lcEtYkGoV9z4XmJIEHLXN5LDR' />

By default, Django checks for the CSRF token in all POST requests. Remember to include the csrf_token tag in all forms that are submitted via POST.

Edit the blog/post/detail.html template and make it look like this:

{% extends "blog/base.html" %}

{% block title %}{{ post.title }}{% endblock %}

{% block content %}

<h1>{{ post.title }}</h1>

<p class="date">

Published {{ post.publish }} by {{ post.author }}

</p>

{{ post.body|linebreaks }}

<p>

<a href="{% url "blog:post_share" post.id %}">

Share this post

</a>

</p>

{% endblock %}

We have added a link to the post_share URL. The URL is built dynamically with the {% url %} template tag provided by Django. We use the namespace called blog and the URL named post_share. We pass the post id as a parameter to build the URL.

Open the shell prompt and execute the following command to start the development server:

python manage.py runserver

Open http://127.0.0.1:8000/blog/ in your browser and click on any post title to view the post detail page.

Under the post body, you should see the link that you just added, as shown in Figure 2.15:

Figure 2.15: The post detail page, including a link to share the post

Click on Share this post, and you should see the page, including the form to share this post by email, as follows:

Figure 2.16: The page to share a post via email

CSS styles for the form are included in the example code in the static/css/blog.css file. When you click on the SEND E-MAIL button, the form is submitted and validated. If all fields contain valid data, you get a success message, as follows:

Figure 2.17: A success message for a post shared via email

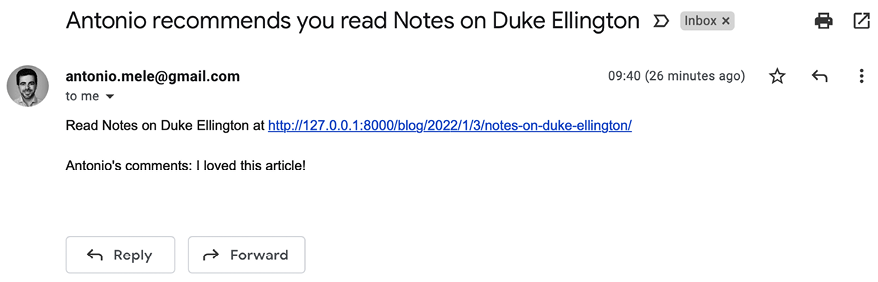

Send a post to your own email address and check your inbox. The email you receive should look like this:

Figure 2.18: Test email sent displayed in Gmail

If you submit the form with invalid data, the form will be rendered again, including all validation errors:

Figure 2.19: The share post form displaying invalid data errors

Most modern browsers will prevent you from submitting a form with empty or erroneous fields. This is because the browser validates the fields based on their attributes before submitting the form. In this case, the form won’t be submitted, and the browser will display an error message for the fields that are wrong. To test the Django form validation using a modern browser, you can skip the browser form validation by adding the novalidate attribute to the HTML <form> element, like <form method="post" novalidate>. You can add this attribute to prevent the browser from validating fields and test your own form validation. After you are done testing, remove the novalidate attribute to keep the browser form validation.

The functionality for sharing posts by email is now complete. You can find more information about working with forms at https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/4.1/topics/forms/.

Creating a comment system

We will continue extending our blog application with a comment system that will allow users to comment on posts. To build the comment system, we will need the following:

- A comment model to store user comments on posts

- A form that allows users to submit comments and manages the data validation

- A view that processes the form and saves a new comment to the database

- A list of comments and a form to add a new comment that can be included in the post detail template

Creating a model for comments

Let’s start by building a model to store user comments on posts.

Open the models.py file of your blog application and add the following code:

class Comment(models.Model):

post = models.ForeignKey(Post,

on_delete=models.CASCADE,

related_name='comments')

name = models.CharField(max_length=80)

email = models.EmailField()

body = models.TextField()

created = models.DateTimeField(auto_now_add=True)

updated = models.DateTimeField(auto_now=True)

active = models.BooleanField(default=True)

class Meta:

ordering = ['created']

indexes = [

models.Index(fields=['created']),

]

def __str__(self):

return f'Comment by {self.name} on {self.post}'

This is the Comment model. We have added a ForeignKey field to associate each comment with a single post. This many-to-one relationship is defined in the Comment model because each comment will be made on one post, and each post may have multiple comments.

The related_name attribute allows you to name the attribute that you use for the relationship from the related object back to this one. We can retrieve the post of a comment object using comment.post and retrieve all comments associated with a post object using post.comments.all(). If you don’t define the related_name attribute, Django will use the name of the model in lowercase, followed by _set (that is, comment_set) to name the relationship of the related object to the object of the model, where this relationship has been defined.

You can learn more about many-to-one relationships at https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/4.1/topics/db/examples/many_to_one/.

We have defined the active Boolean field to control the status of the comments. This field will allow us to manually deactivate inappropriate comments using the administration site. We use default=True to indicate that all comments are active by default.

We have defined the created field to store the date and time when the comment was created. By using auto_now_add, the date will be saved automatically when creating an object. In the Meta class of the model, we have added ordering = ['created'] to sort comments in chronological order by default, and we have added an index for the created field in ascending order. This will improve the performance of database lookups or ordering results using the created field.

The Comment model that we have built is not synchronized into the database. We need to generate a new database migration to create the corresponding database table.

Run the following command from the shell prompt:

python manage.py makemigrations blog

You should see the following output:

Migrations for 'blog':

blog/migrations/0003_comment.py

- Create model Comment

Django has generated a 0003_comment.py file inside the migrations/ directory of the blog application. We need to create the related database schema and apply the changes to the database.

Run the following command to apply existing migrations:

python manage.py migrate

You will get an output that includes the following line:

Applying blog.0003_comment... OK

The migration has been applied and the blog_comment table has been created in the database.

Adding comments to the administration site

Next, we will add the new model to the administration site to manage comments through a simple interface.

Open the admin.py file of the blog application, import the Comment model, and add the following ModelAdmin class:

from .models import Post, Comment

@admin.register(Comment)

class CommentAdmin(admin.ModelAdmin):

list_display = ['name', 'email', 'post', 'created', 'active']

list_filter = ['active', 'created', 'updated']

search_fields = ['name', 'email', 'body']

Open the shell prompt and execute the following command to start the development server:

python manage.py runserver

Open http://127.0.0.1:8000/admin/ in your browser. You should see the new model included in the BLOG section, as shown in Figure 2.20:

Figure 2.20: Blog application models on the Django administration index page

The model is now registered on the administration site.

In the Comments row, click on Add. You will see the form to add a new comment:

Figure 2.21: Blog application models on the Django administration index page

Now we can manage Comment instances using the administration site.

Creating forms from models

We need to build a form to let users comment on blog posts. Remember that Django has two base classes that can be used to create forms: Form and ModelForm. We used the Form class to allow users to share posts by email. Now we will use ModelForm to take advantage of the existing Comment model and build a form dynamically for it.

Edit the forms.py file of your blog application and add the following lines:

from .models import Comment

class CommentForm(forms.ModelForm):

class Meta:

model = Comment

fields = ['name', 'email', 'body']

To create a form from a model, we just indicate which model to build the form for in the Meta class of the form. Django will introspect the model and build the corresponding form dynamically.

Each model field type has a corresponding default form field type. The attributes of model fields are taken into account for form validation. By default, Django creates a form field for each field contained in the model. However, we can explicitly tell Django which fields to include in the form using the fields attribute or define which fields to exclude using the exclude attribute. In the CommentForm form, we have explicitly included the name, email, and body fields. These are the only fields that will be included in the form.

You can find more information about creating forms from models at https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/4.1/topics/forms/modelforms/.

Handling ModelForms in views

For sharing posts by email, we used the same view to display the form and manage its submission. We used the HTTP method to differentiate between both cases; GET to display the form and POST to submit it. In this case, we will add the comment form to the post detail page, and we will build a separate view to handle the form submission. The new view that processes the form will allow the user to return to the post detail view once the comment has been stored in the database.

Edit the views.py file of the blog application and add the following code:

from django.shortcuts import render, get_object_or_404, redirect

from .models import Post, Comment

from django.core.paginator import Paginator, EmptyPage,

PageNotAnInteger

from django.views.generic import ListView

from .forms import EmailPostForm, CommentForm

from django.core.mail import send_mail

from django.views.decorators.http import require_POST

# ...

@require_POST

def post_comment(request, post_id):

post = get_object_or_404(Post, id=post_id, status=Post.Status.PUBLISHED)

comment = None

# A comment was posted

form = CommentForm(data=request.POST)

if form.is_valid():

# Create a Comment object without saving it to the database

comment = form.save(commit=False)

# Assign the post to the comment

comment.post = post

# Save the comment to the database

comment.save()

return render(request, 'blog/post/comment.html',

{'post': post,

'form': form,

'comment': comment})

We have defined the post_comment view that takes the request object and the post_id variable as parameters. We will be using this view to manage the post submission. We expect the form to be submitted using the HTTP POST method. We use the require_POST decorator provided by Django to only allow POST requests for this view. Django allows you to restrict the HTTP methods allowed for views. Django will throw an HTTP 405 (method not allowed) error if you try to access the view with any other HTTP method.

In this view, we have implemented the following actions:

- We retrieve a published post by its

idusing theget_object_or_404()shortcut. - We define a

commentvariable with the initial valueNone. This variable will be used to store the comment object when it gets created. - We instantiate the form using the submitted

POSTdata and validate it using theis_valid()method. If the form is invalid, the template is rendered with the validation errors. - If the form is valid, we create a new

Commentobject by calling the form’ssave()method and assign it to thenew_commentvariable, as follows:comment = form.save(commit=False) - The

save()method creates an instance of the model that the form is linked to and saves it to the database. If you call it usingcommit=False, the model instance is created but not saved to the database. This allows us to modify the object before finally saving it.The

save()method is available forModelFormbut not forForminstances since they are not linked to any model.

- We assign the post to the comment we created:

comment.post = post - We save the new comment to the database by calling its

save()method:comment.save() - We render the template

blog/post/comment.html, passing thepost,form, andcommentobjects in the template context. This template doesn’t exist yet; we will create it later.

Let’s create a URL pattern for this view.

Edit the urls.py file of the blog application and add the following URL pattern to it:

from django.urls import path

from . import views

app_name = 'blog'

urlpatterns = [

# Post views

# path('', views.post_list, name='post_list'),

path('', views.PostListView.as_view(), name='post_list'),

path('<int:year>/<int:month>/<int:day>/<slug:post>/',

views.post_detail,

name='post_detail'),

path('<int:post_id>/share/',

views.post_share, name='post_share'),

path('<int:post_id>/comment/',

views.post_comment, name='post_comment'),

]

We have implemented the view to manage the submission of comments and their corresponding URL. Let’s create the necessary templates.

Creating templates for the comment form

We will create a template for the comment form that we will use in two places:

- In the post detail template associated with the

post_detailview to let users publish comments - In the post comment template associated with the

post_commentview to display the form again if there are any form errors.

We will create the form template and use the {% include %} template tag to include it in the two other templates.

In the templates/blog/post/ directory, create a new includes/ directory. Add a new file inside this directory and name it comment_form.html.

The file structure should look as follows:

templates/

blog/

post/

includes/

comment_form.html

detail.html

list.html

share.html

Edit the new blog/post/includes/comment_form.html template and add the following code:

<h2>Add a new comment</h2>

<form action="{% url "blog:post_comment" post.id %}" method="post">

{{ form.as_p }}

{% csrf_token %}

<p><input type="submit" value="Add comment"></p>

</form>

In this template, we build the action URL of the HTML <form> element dynamically using the {% url %} template tag. We build the URL of the post_comment view that will process the form. We display the form rendered in paragraphs and we include {% csrf_token %} for CSRF protection because this form will be submitted with the POST method.

Create a new file in the templates/blog/post/ directory of the blog application and name it comment.html.

The file structure should now look as follows:

templates/

blog/

post/

includes/

comment_form.html

comment.html

detail.html

list.html

share.html

Edit the new blog/post/comment.html template and add the following code:

{% extends "blog/base.html" %}

{% block title %}Add a comment{% endblock %}

{% block content %}

{% if comment %}

<h2>Your comment has been added.</h2>

<p><a href="{{ post.get_absolute_url }}">Back to the post</a></p>

{% else %}

{% include "blog/post/includes/comment_form.html" %}

{% endif %}

{% endblock %}

This is the template for the post comment view. In this view, we expect the form to be submitted via the POST method. The template covers two different scenarios:

- If the form data submitted is valid, the

commentvariable will contain thecommentobject that was created, and a success message will be displayed. - If the form data submitted is not valid, the

commentvariable will beNone. In this case, we will display the comment form. We use the{% include %}template tag to include thecomment_form.htmltemplate that we have previously created.

Adding comments to the post detail view

Edit the views.py file of the blog application and edit the post_detail view as follows:

def post_detail(request, year, month, day, post):

post = get_object_or_404(Post,

status=Post.Status.PUBLISHED,

slug=post,

publish__year=year,

publish__month=month,

publish__day=day)

# List of active comments for this post

comments = post.comments.filter(active=True)

# Form for users to comment

form = CommentForm()

return render(request,

'blog/post/detail.html',

{'post': post,

'comments': comments,

'form': form})

Let’s review the code we have added to the post_detail view:

- We have added a QuerySet to retrieve all active comments for the post, as follows:

comments = post.comments.filter(active=True) - This QuerySet is built using the

postobject. Instead of building a QuerySet for theCommentmodel directly, we leverage thepostobject to retrieve the relatedCommentobjects. We use thecommentsmanager for the relatedCommentobjects that we previously defined in theCommentmodel, using therelated_nameattribute of theForeignKeyfield to thePostmodel. - We have also created an instance of the comment form with

form = CommentForm().

Adding comments to the post detail template

We need to edit the blog/post/detail.html template to implement the following:

- Display the total number of comments for a post

- Display the list of comments

- Display the form for users to add a new comment

We will start by adding the total number of comments for a post.

Edit the blog/post/detail.html template and change it as follows:

{% extends "blog/base.html" %}

{% block title %}{{ post.title }}{% endblock %}

{% block content %}

<h1>{{ post.title }}</h1>

<p class="date">

Published {{ post.publish }} by {{ post.author }}

</p>

{{ post.body|linebreaks }}

<p>

<a href="{% url "blog:post_share" post.id %}">

Share this post

</a>

</p>

{% with comments.count as total_comments %}

<h2>

{{ total_comments }} comment{{ total_comments|pluralize }}

</h2>

{% endwith %}

{% endblock %}

We use the Django ORM in the template, executing the comments.count() QuerySet. Note that the Django template language doesn’t use parentheses for calling methods. The {% with %} tag allows you to assign a value to a new variable that will be available in the template until the {% endwith %} tag.

The {% with %} template tag is useful for avoiding hitting the database or accessing expensive methods multiple times.

We use the pluralize template filter to display a plural suffix for the word “comment,” depending on the total_comments value. Template filters take the value of the variable they are applied to as their input and return a computed value. We will learn more about template filters in Chapter 3, Extending Your Blog Application.

The pluralize template filter returns a string with the letter “s” if the value is different from 1. The preceding text will be rendered as 0 comments, 1 comment, or N comments, depending on the number of active comments for the post.

Now, let’s add the list of active comments to the post detail template.

Edit the blog/post/detail.html template and implement the following changes:

{% extends "blog/base.html" %}

{% block title %}{{ post.title }}{% endblock %}

{% block content %}

<h1>{{ post.title }}</h1>

<p class="date">

Published {{ post.publish }} by {{ post.author }}

</p>

{{ post.body|linebreaks }}

<p>

<a href="{% url "blog:post_share" post.id %}">

Share this post

</a>

</p>

{% with comments.count as total_comments %}

<h2>

{{ total_comments }} comment{{ total_comments|pluralize }}

</h2>

{% endwith %}

{% for comment in comments %}

<div class="comment">

<p class="info">

Comment {{ forloop.counter }} by {{ comment.name }}

{{ comment.created }}

</p>

{{ comment.body|linebreaks }}

</div>

{% empty %}

<p>There are no comments.</p>

{% endfor %}

{% endblock %}

We have added a {% for %} template tag to loop through the post comments. If the comments list is empty, we display a message that informs users that there are no comments for this post. We enumerate comments with the {{ forloop.counter }} variable, which contains the loop counter in each iteration. For each post, we display the name of the user who posted it, the date, and the body of the comment.

Finally, let’s add the comment form to the template.

Edit the blog/post/detail.html template and include the comment form template as follows:

{% extends "blog/base.html" %}

{% block title %}{{ post.title }}{% endblock %}

{% block content %}

<h1>{{ post.title }}</h1>

<p class="date">

Published {{ post.publish }} by {{ post.author }}

</p>

{{ post.body|linebreaks }}

<p>

<a href="{% url "blog:post_share" post.id %}">

Share this post

</a>

</p>

{% with comments.count as total_comments %}

<h2>

{{ total_comments }} comment{{ total_comments|pluralize }}

</h2>

{% endwith %}

{% for comment in comments %}

<div class="comment">

<p class="info">

Comment {{ forloop.counter }} by {{ comment.name }}

{{ comment.created }}

</p>

{{ comment.body|linebreaks }}

</div>

{% empty %}

<p>There are no comments.</p>

{% endfor %}

{% include "blog/post/includes/comment_form.html" %}

{% endblock %}

Open http://127.0.0.1:8000/blog/ in your browser and click on a post title to take a look at the post detail page. You will see something like Figure 2.22:

Figure 2.22: The post detail page, including the form to add a comment

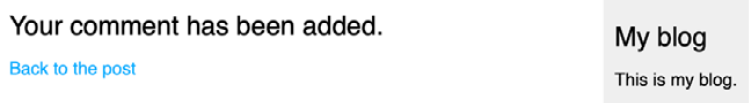

Fill in the comment form with valid data and click on Add comment. You should see the following page:

Figure 2.23: The comment added success page

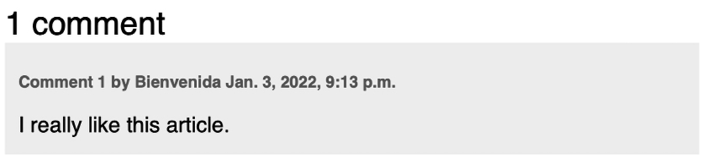

Click on the Back to the post link. You should be redirected back to the post detail page, and you should be able to see the comment that you just added, as follows:

Figure 2.24: The post detail page, including a comment

Add one more comment to the post. The comments should appear below the post contents in chronological order, as follows:

Figure 2.25: The comment list on the post detail page

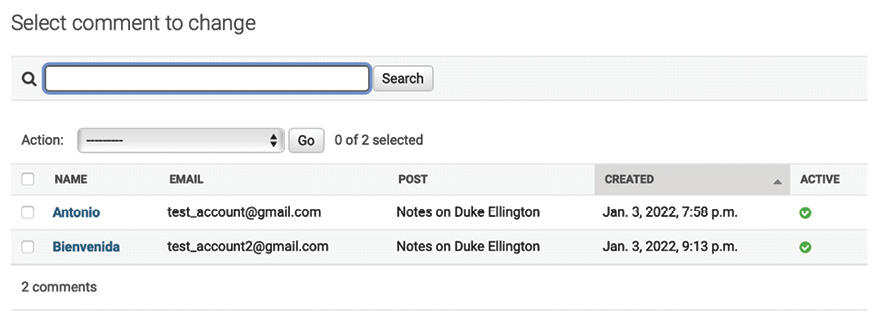

Open http://127.0.0.1:8000/admin/blog/comment/ in your browser. You will see the administration page with the list of comments you created, like this:

Figure 2.26: List of comments on the administration site

Click on the name of one of the posts to edit it. Uncheck the Active checkbox as follows and click on the Save button:

Figure 2.27: Editing a comment on the administration site

You will be redirected to the list of comments. The Active column will display an inactive icon for the comment, as shown in Figure 2.28:

Figure 2.28: Active/inactive comments on the administration site

If you return to the post detail view, you will note that the inactive comment is no longer displayed, neither is it counted for the total number of active comments for the post:

Figure 2.29: A single active comment displayed on the post detail page

Thanks to the active field, you can deactivate inappropriate comments and avoid showing them on your posts.

Additional resources

The following resources provide additional information related to the topics covered in this chapter:

- Source code for this chapter – https://github.com/PacktPublishing/Django-4-by-example/tree/main/Chapter02

- URLs utility functions – https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/4.1/ref/urlresolvers/

- URL path converters – https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/4.1/topics/http/urls/#path-converters

- Django paginator class – https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/4.1/ref/paginator/

- Introduction to class-based views – https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/4.1/topics/class-based-views/intro/

- Sending emails with Django – https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/4.1/topics/email/

- Django form field types – https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/4.1/ref/forms/fields/

- Working with forms – https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/4.1/topics/forms/

- Creating forms from models – https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/4.1/topics/forms/modelforms/

- Many-to-one model relationships – https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/4.1/topics/db/examples/many_to_one/

Summary

In this chapter, you learned how to define canonical URLs for models. You created SEO-friendly URLs for blog posts, and you implemented object pagination for your post list. You also learned how to work with Django forms and model forms. You created a system to recommend posts by email and created a comment system for your blog.

In the next chapter, you will create a tagging system for the blog. You will learn how to build complex QuerySets to retrieve objects by similarity. You will learn how to create custom template tags and filters. You will also build a custom sitemap and feed for your blog posts and implement a full-text search functionality for your posts.