CONTENTS OF THIS CHAPTER

This chapter covers the following topics:

- the rationale for business analysis;

- the role of the business analyst;

- the place of business analysis in the systems development lifecycle;

- the business analysis process model and activities;

- the potential outcomes from business analysis.

INTRODUCTION

All organisations can improve how they work. Whether there are opportunities to increase the efficiency of the processes, the capability of the people or to improve the IT systems, possibilities for improvement are many and varied. Sometimes, organisations instigate change initiatives where several of these factors are present. Organisations have to change in order to continue to offer up-to-date products and services, and to ensure they are responsive to customers’ needs. Often, change projects address a recognised issue or specific problem. However, it is all too frequent that an organisation sets up a project to replace an IT system – perhaps because a new software package has become available or because there is an assumption that IT will cut costs – without investigating the need before identifying the solution. Inevitably, this leads to problems as with the best will in the world, a project manager can deliver the IT system as specified but this may not address the real underlying issues. Management thinker Peter Drucker provided a most appropriate comment:

Management is doing things right; leadership is doing the right things.

The distinction between ‘doing things right’ and ‘doing the right things’ is very important. We can spend a long time following the standards or a selected approach, only to find that what is delivered doesn’t meet the need. While there is much discussion about Agile software development at the moment, we also need to think about the most relevant ways of addressing business problems. In some cases, software may not be part of the most appropriate solution as there may be a less expensive and equally valuable process workaround available. In this chapter, we look at the role of the business analyst in ensuring that change projects focus on ‘doing the right things’ by understanding the real business need and offering relevant solutions.

BUSINESS ANALYSIS

Business analysis as a specialist discipline emerged in the early 1990s due to a combination of factors:

- The increasing dissatisfaction on the part of business staff (the ‘users’) with the quality of the IT systems delivered. There were regular project failures but, even where the systems were delivered, many business staff felt that there had been a lack of understanding of their requirements. They felt that the IT staff did not ‘speak the business language’ and complained that many IT departments delivered what they thought was important without really addressing factors such as how people worked, the environment for the systems and how the less straightforward cases would be handled. On one project from this era, the end users were required to use communal terminals, as it had been assessed that they would only need access to the system a few hours each day. On the first day of live running, it emerged that they all needed access during the same few hours in order to fit with other elements in the overall business process. Chaos ensued, as twice as many people as terminals tried to get onto the system.

- The recognition that IT was no longer a department of mystique and wonder and that the systems were actually there to meet the business needs. More and more people were acquiring familiarity with technology and were becoming more insistent on expressing their views. They gained increasing awareness of the potential for the technology and, as a result, were also aware of when this potential was not realised. The business departments gained recognition as the ‘owners’ of the systems – after all, the IT systems existed to support the work of the business, not the other way around. In line with this, the perception of the IT systems shifted and a realisation developed that they were not an end in themselves but a means to successful business operations.

- The development of the outsourcing business model created an environment where IT systems were developed and supported outside the organisation. This placed additional pressures on the organisation to improve the understanding and specification of the requirements to be met by the systems. A study by David Feeny and Leslie Willcocks (Oxford Institute of Information Management, University of Oxford, 1998) identified a number of key skills required within organisations that have outsourced IT. This report specifically identified business systems thinking, a core element of the business analyst role, as a key skill that needs to be retained within organisations operating an outsourcing arrangement.

- The use of approaches such as systems thinking also helped build an awareness that IT systems may enable, or even be central, to business improvements but they were not the sole element. Other factors such as people and processes were also important if the business changes were to be facilitated successfully by the IT systems and the predicted benefits were to be achieved.

Rationale for business analysis

Business analysis developed as a response to the issues described above, initially to translate business needs and facilitate communication between the business and IT staff. However, business analysis quickly developed to focus on addressing business problems and opportunities, taking a forward-looking approach rather than just addressing existing issues. Proactivity is an essential part of the business analyst toolkit, as is root cause analysis. There is little point in identifying a solution if we don’t understand the problem we are trying to solve.

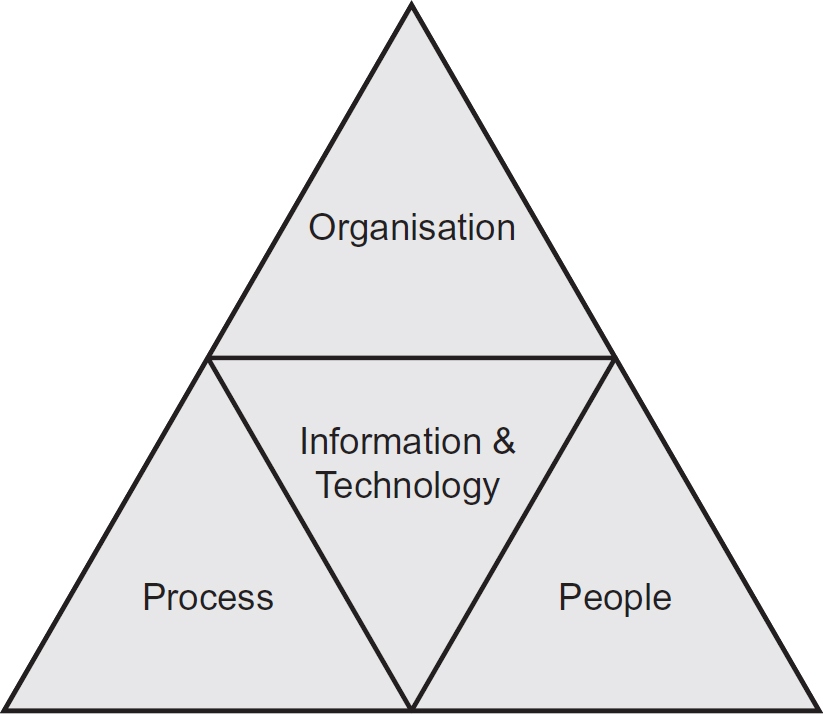

From the outset, business analysis has been described as a holistic discipline, whereby all aspects of a business system, including all of the elements that can contribute to a business problem, are considered. The POPIT™ model in Figure 3.1 is often used both to identify the different elements that form a business system and to support holistic analysis by ensuring that all of these elements – and their interactions - are considered.

Figure 3.1 POPIT™ model (© Assist Knowledge Development)

Originally, business analysis provided a link between business and IT, which was sometimes known as ‘bridging’. However, it has developed significantly over the last two decades and is now recognised as a discipline that is vital if business needs are to be addressed and business change programmes are to deliver successful outcomes. Many senior business analysts work at an advisory level in the organisation, suggesting or even deciding business change priorities, and identifying how change initiatives can help the organisation develop and improve. Although IT is often a driver for a change project, it is rarely the entire solution. It is the job of the business analyst to understand the business needs and identify what should be changed if these needs are to be addressed. While it is unusual that IT does not form part of the solution, with the economic difficulties faced by many organisations and the need for speedy responses to change, it is important to consider whether a non-IT option would be relevant and valuable.

Definition of business analysis

BCS, The Chartered Institute for IT, offers the following definition of business analysis:

An internal consultancy role which has the responsibility for investigating business situations, identifying and evaluating options for improving business systems, defining requirements and ensuring the effective use of information systems in meeting the needs of the business.

It is useful to analyse the component elements of this definition:

- Internal consultancy role – business analysts offer advice and guidance to the organisation. To do this, they need to have an extensive toolkit of skills that will enable them to provide insights and valuable guidance.

- Investigating business situations – the emphasis here is on the business situation not the existing IT system. This involves the consideration of several aspects of the situation; these are described below using the POPIT™ model from Figure 3.1.

- Identifying and evaluating options – the need to consider options is extremely important if an organisation is to gain the most return on any investment. Sometimes, a business analyst may look at a problem and identify a solution that requires only limited or possible no IT change. For example, where a manual workaround is possibly a more efficient and cost-effective solution.

- Defining requirements – a key activity in business analysis which is explored in outline below and in greater detail in Chapter 5.

- Ensuring the effective use of information systems – working with the business to ensure that any solution is relevant and of value, and providing support throughout the lifecycle to facilitate a successful transition to the new system.

- Meeting the needs of the business – the key driver and context for business analysis.

The International Institute for Business Analysis™ (IIBA®), offers a similar definition:

Business analysis is the practice of enabling change in an organizational context, by defining needs and recommending solutions that deliver value to stakeholders.

THE PLACE OF BUSINESS ANALYSIS IN THE DEVELOPMENT LIFECYCLE

Business analysis is extremely important when investigating ideas or initiatives for change. However, it is not required just at the outset but across the entire business change and Systems Development lifecycles. Figure 3.2 is an extended version of the ‘V’ model explained in Chapter 2; this model helps to position business analysis within a Systems Development lifecycle and identifies the major activities conducted by the business analysts (BAs).

Figure 3.2 The extended ‘V’ model

This version of the ‘V’ model shows the major activities carried out by business analysts, highlighting that business analysis is conducted to investigate the business situation and develop a business case. The business case sets out the options and recommendations that will address any problems and this provides the basis for the benefits management and realisation work. The selected option is then explored further in order to define the business requirements, which then provide the basis for the user acceptance testing. This model is based upon a Waterfall lifecycle, but can be adapted for Agile software development; the activities outside the business analysis area would be undertaken using an Agile approach. So, the business requirements would form the basis for deciding upon the content for each iteration and they would then be elaborated, developed and tested using Agile techniques.

Although this model shows the key areas of work for the business analysts – feasibility study, requirements definition, user acceptance testing and benefits realisation – the work of the business analyst continues throughout the development lifecycle. The core business analysis activities and the stages where business analysis occupies more of a supporting role are discussed below.

Feasibility study

The feasibility study stage of the lifecycle is concerned with investigating a situation in order to uncover the issues and then identifying and evaluating possible options to resolve those issues. This stage is essential if the root causes of business problems are to be uncovered – after all, it is important to understand the problem to be solved before identifying solutions. This is a key activity in business analysis, as it is the point where investigation and analysis is vital if the most appropriate way forward is to be determined.

Figure 3.3 Business analysis process model

Figure 3.3 identifies some of the key activities conducted by business analysts. The model shows how the organisational strategy and objectives need to provide the context for the business analysis work; there would be little point in recommending a solution that contradicted the defined strategy and direction of the organisation. The four initial activities shown in the model comprise the feasibility study work and are concerned with investigating business situations and analysing stakeholders’ needs.

The analysts need to find out exactly where any problems may be found and locate the root causes of those problems. They need to ensure that any stated issues are not just symptoms of an underlying problem but the actual cause. They also need to engage with stakeholders to ensure that they understand different perspectives on the situation – one person’s problem could be another person’s minor irritation or, even, non-issue. One of the approaches used by business analysts when analysing business needs is to identify stakeholders’ perspectives – based around their ‘world view’ of the system – and they use these perspectives to consider what the system would need to do and what value it would need to deliver in order to fulfil each world view. This provides the basis for developing an overview model, that sets out the high-level activities required by a business system in the light of a particular perspective. This is a conceptual model, which is useful for identifying areas that are problematic or even absent.

The business analysts sometimes investigate activities in detail by considering the business processes required to perform the work. They may develop models of the existing processes – known as the ‘as is’ processes – and the new processes to be adopted in the future – the ‘to be’ processes. Using the high level model of business activities and the more specific business process models, the business analysts can analyse the needs by conducting ‘gap analysis’, identifying where there are deficiencies that need to be addressed or changes that need to be made, if the organisation is to move to a new business system and address the current issues.

This work is essential if there is to be a focus on the delivery of value, both by the project and by the business, and if relevant options for change are to be identified. While many options may be identified initially, they need to be reduced to a manageable number as it is unlikely that the BAs would have sufficient time to thoroughly evaluate more than three options. The evaluation of options forms part of the business case where the shortlisted options are assessed from the financial, business and technical perspectives.

- Financial feasibility involves examining the costs and benefits associated with a particular option in order to ensure that the financial return makes the option worthwhile. Techniques such as payback (break-even), discounted cash flow and internal rate of return are used to determine the level of financial return likely to be delivered by the proposed option. These techniques are described further in Chapter 4.

- Business feasibility involves considering each option to determine whether or not it will ‘fit’ with the organisation. This may require checking the alignment of the option with the business architecture or considering whether the option is in line with the culture and management style of the organisation. For example, an option may propose that some work is outsourced but the business architecture may incorporate that work within the internal processes and capabilities; alternatively, an option may be predicated on an empowered team, but this may be contrary to the more directive nature of the organisation and its management style.

- Technical feasibility checking is important; first, to ensure that the technology exists to support a proposed option, and second to ensure that the technology will meet the needs of the organisation. Even if the desired technology is available, it is also important to confirm that it does align with the organisation’s technical strategy – for example, the technology may only be available on a particular hardware platform, whereas the organisation has standardised on a different platform. Further, there may be requirements that specify non-functional aspects such as processing speed, capacity or robustness and it is important to check that they can be delivered by the technology.

While the business analyst will contribute to the business case by suggesting how the business needs might be met, the business case is the responsibility of the project sponsor, whose role is to ensure that there is a return on the investment made by the business. The feasibility stage is where the business situation is thoroughly investigated to ensure that the most relevant solution is selected – that the project is ‘doing the right things’. Without this stage, a systems development project might be defined without due consideration and a solution may be selected that is at best less relevant than an alternative and at worst fails to meet the business need at all.

Define requirements

Once the solution has been selected by the business decision-makers, the project moves into the define requirements stage of the process model. This is when the business analysts again undertake vital work. The high-level, outline requirements that have been gathered during the feasibility study are explored further. One of the key aspects of business analysis is ensuring that the business receives the solution that will best meet its need. In order to do this, the business requirements must be known and must be defined in sufficient detail to ensure that any development work will address business requirements. After all, if a detailed system requirement does not support a business requirement, there is little point in delivering it. Technical requirements also need to be defined to ensure that any IT solution is aligned with the technical policies and architecture adopted by the organisation.

A hierarchy of requirements may be developed, showing the links between the business and technical high-level requirements with the more detailed solution requirements. The solution requirements fall into two categories: functional requirements define what functions the system is to deliver; non-functional requirements define the level of service the system is to provide in areas such as processing speed and availability. So, we could have a business requirement that states the need to comply with data protection legislation, which is linked to a functional requirement to enable customers to keep their data up-to-date, and is also linked to a non-functional requirement to ensure that access to personal data is restricted to the relevant person.

In the course of eliciting the requirements, the business analysts may interview business managers and staff, examine documentation, run workshops or utilise a range of other elicitation techniques. These techniques are explained in further detail in Chapter 5. Requirements analysis is core to the business analyst role and is vital if an IT system is to be of value to the organisation.

The requirements need to be defined in sufficient detail to meet the needs of the adopted project approach. Should the project adopt a linear approach – for example using the ‘V’ model, where the stages are performed in sequence – the requirements will need to be defined in detail, with the definitions being supported by models such as use case diagrams and class models; these models are discussed in Chapter 7. Alternatively, where an evolutionary approach, possibly using Agile techniques, is adopted, the requirements may be defined in less detail as they are then explored further when the business analysts work alongside the staff and developers during the development of the system. Chapter 2 discusses the range of lifecycles and approaches available to the project team.

The business analysts perform the majority of the requirements analysis work, eliciting, analysing, modelling and documenting requirements. Requirements Engineering is the standard framework used here; this framework is described in Chapter 5.

Deliver solution

This stage of the business analysis process involves the acquisition of the solution (including the IT solution, which may be built or bought off-the-shelf) and its implementation. If an off-the-shelf software solution is required, the requirements document provides the basis for evaluating the acceptability of a particular software package and the business analysts may be involved in this evaluation. With regard to the development of the IT solution, business analysts have specific involvement as described below.

Design, development and testing

During the design, development and testing of a system, business analysts typically need to support the work as follows: by ensuring that any changes to requirements are analysed for impacts, for example on other requirements, on costs or on benefits; by helping the business staff explain their detailed requirements such that the development team can understand what is needed. Business analysts may also need to support these stages by clarifying the requirements or revisiting them where there are inconsistencies. They should have a constant eye on the original business needs defined and on the link to the detailed development work. If an Agile approach such as Scrum is to be used, the business analysts may be needed to support the development work by ensuring that communication between the business staff (end users) and the development team is clear; it is often a problem when jargon or organisational business language is used and the business analyst is invaluable in helping to overcome this. If this approach is used, the business analyst may be needed to maintain the requirements in the product backlog, for example by helping with prioritisation, defining the content to be delivered in the development sprints, and so on.

User acceptance testing

Although a system is tested by the software testing team, it is important that the stakeholders who will be using the system in their daily work – the business users – also test the system. When the business users test the system, they want to ensure that the data entered produces the expected results. To do this they undertake user acceptance testing (UAT) where they enter pre-defined sets of data that are designed to follow pathways, known as scenarios, through the software system. This approach is followed to ensure that the system behaves as required and expected, and helps the users confirm that the system has delivered their requirements and that they are happy to accept it. As the UAT is based upon the requirements, the business analysts assist the users both in defining the different scenarios to be tested and identifying the data to be used to test each scenario. The analysts may use techniques such as activity diagrams or flow charts, decision trees and decision tables, to define the scenarios and the different combinations of data. These techniques can be particularly useful where there are a lot of business rules to be applied within the system. They can also help to identify exception situations, where the standard process is not followed or an unusual set of data occurs. UAT requires analysis if it is to be conducted thoroughly so the involvement of the business analysts is extremely important. UAT is explored in further depth in Chapter 11.

Implementation

The implementation of the system has to be planned carefully, and at an early stage in the project, in order to minimise disruption and ensure maximum adoption. The business analysts are often heavily involved in this work, as they can help to ensure that the new ways of working are defined clearly. The users may require training in the new working procedures and may need support as they begin to adopt the new processes, practices and systems. The business analysts, having been instrumental in uncovering the business needs and identifying the means of achieving them, often define and deliver the training, and provide ongoing support for the users during the implementation stage.

Post-implementation review/benefits realisation

Each project should be reviewed once it has delivered the solution in order to identify where the work has gone well, the lessons to be learned and any outstanding issues. This is known as a post-implementation review. Achieving the business needs is a key part of the context for assessing project success, as this was the initial justification for conducting the project and should have formed the ongoing rationale for its continuation. While the post-implementation review is the responsibility of the project manager and project sponsor, the business analysts may be required to provide information to support the review.

It is also important to carry out a benefits review, although this is typically at a later point in time. This review revisits the benefits defined in the business case for the project and evaluates whether or not they have been realised. Delivering the business benefits predicted for business change projects has become increasingly important. IT projects may require significant investment and organisations need to ensure that there has been a return on that investment. When analysing the business needs, the business analysts will have contributed to the development of the business case and may have been involved in identifying and quantifying the benefits. During the lifetime of the projects, they will have been required to assess any change requests in order to determine the impact on the project and the business case. When the benefits are reviewed, the business analyst may need to help identify actions that may be taken to help deliver benefits where they have not yet been realised. In the light of this, it is important that the business analysts are involved in the benefits review.

Post-implementation and benefits reviews are discussed further in Chapter 13.

OUTCOMES FROM BUSINESS ANALYSIS

Business analysis offers a holistic approach to addressing business needs. This means that a problem situation is investigated to identify the root causes and the different elements that will need to be changed to address the problem. While it is likely that an IT system will be required as part of the solution, it is unlikely that it will form the entire solution; other changes will be required to the business system. As shown in Figure 3.1 above, there are four major elements of change: information and technology, people, processes and organisation. These are described below.

IT/IS change

Information technology provides the means of delivering information systems. The systems deliver functionality and information to enable the work of the organisation to be conducted. Often the new software is the core of a larger business change initiative, but sometimes there may just be a need to introduce a later version of a software product or change to a new system in order to align with organisational technical standards and architecture. The early work by the business analysts in identifying the business needs and analysing how they might be addressed is vital if the technological solution is to support the business as required. For example, a system must provide the information needed to run the organisation at the operational, tactical and strategic levels. To do this, early analysis is needed in order to understand the business requirements to be met including the management information requirements. There have been many cases where an IT system has been delivered yet has failed to meet the needs of the business. In some cases, these systems have been abandoned or used to only a limited extent. The only way to avoid this is to ensure that the business need to be addressed is understood at the outset and kept in mind throughout the development process.

Process change

The introduction of a new IT system also necessitates changes to the business processes. They may need to be redesigned to work with the new software in order to ensure that the aims of the change, typically improved efficiency and accuracy, are achieved. The changes to the processes may include removing some of the individual tasks (possibly because they are performed automatically by the software), changing the sequence of the tasks and reducing the number of times the documents in the process are exchanged between different actors. The revised processes need to be documented in a clear manner so that they can be communicated to the staff required to carry out the work. Any changes to a business process are likely to necessitate changes to the skills of the staff, the technology support and the organisation.

People change

When a new IT system is to be introduced, there is inevitably an impact upon the processes and, correspondingly, on the work the staff carry out. At the very least, the staff need to adapt from using one system to using another. However, it is rarely a simple transition, as a new IT system should provide additional support for the processes and tasks and, as a result, the people need to do their work differently. It is important to consider the changes and the impact upon the staff. For example, do they require additional skills in order to carry out their job? Will there be an effect upon staff motivation? Will the communication channels change? Have the business objectives changed and do the staff need to be made aware of this? Whatever the impacts on the people, the business analysts need to identify what should happen to ensure that the staff feel trained and supported, are able to adapt to the new system and continue to perform their work effectively.

Organisation change

It is often the case that there is a need for job roles to be redefined when a new system and revised business processes are introduced. This job redefinition is required in order to reflect any changed responsibilities or the need to perform different tasks. Sometimes, there are new ways of working that cause extensive changes to job roles and these cause organisational structure changes, such as the merger of teams. For example, if some of the administrative work is automated, clerical tasks are reduced which will result in job roles that are revised significantly or even removed. If teams are merged, this will require changes to the management structure and the nature of the new job roles may result in a different management style. For example, if the users are to be given additional information so that they are able to make more decisions, the style may have to become more facilitative rather than directive. Similarly, any new jobs, and their corresponding responsibilities, will need to be defined. The communications between teams, departments or individuals may also change. In such situations, the organisation will need to adapt in many ways to accommodate the introduction of the new system.

CONCLUSION

Analysing the business needs is a vital step if organisations are to understand the problems to be addressed and identify relevant solutions. Failing to carry out this work can lead to unnecessary investment in projects that ultimately do not deliver the required benefits to the organisation. The business analyst plays an important role in this pre-project stage, uncovering the root causes of problems, investigating what is needed to take things forward and evaluating the potential actions to be taken. In a time of change and economic uncertainty, it is important to ensure that investment funds are not wasted, project teams are focused on ‘doing the right things’ and we deliver successful IT systems and business changes.

REFERENCES

Drucker, P. (2001) The essential Drucker. Harper Business, New York.

Paul, D., Yeates, D. and Cadle, J. (2014) Business analysis (3rd edition). BCS, Swindon.

Various authors (2009) A guide to the business analysis body of knowledge® (BABOK® Guide) Version 2. IIBA, Toronto.

FURTHER READING

Cadle, J., Paul, D. and Turner, P. (2014) Business analysis techniques: 99 essential tools for success (2nd edition). BCS, Swindon.

Checkland, P. (1993) Systems thinking, systems practice. John Wiley, Chichester.

Skidmore, S. and Eva, M. (2004) Introducing systems development. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke.