12

Erotic Analysis

Of course, John thought. Sherlock had seen how frightened he’d been. This was … logical, or something. The quickest way to get John calm so they could get out of there. Why else would Sherlock ever hug anybody? Sherlock’s grip loosened, but he didn’t exactly let go. Instead, he placed his hands on John’s shoulders, and pulled back to study his face. John tried not to look like too much of a mess, even though he felt like a raw bundle of nerves. It didn’t help that one of Sherlock’s hands had moved to the back of John’s neck and was tracing along the top of his spine. It was sending strange electric pulses throughout the doctor’s body. Why was Sherlock doing that? It was the last coherent thought John had before he blinked, and Sherlock’s lips were pressed against his … Before he could even piece a thought together, Sherlock turned on his heel and began to walk toward the exit. John stared after him.

“Are you coming?”1

For casual viewers of the popular BBC crime drama Sherlock, based on Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories, the preceding story fragment probably seems strange and perhaps even a little unsettling. After all, it recounts a sexual encounter between the show’s titular character, Sherlock Holmes, and his longtime sidekick, Dr. John Watson, an encounter that never actually transpired on the show. But for serious fans of the Sherlock Holmes universe, it is just one of the hundreds of stories – each written by fans – in which Sherlock and Watson engage in sexual relations. It typifies a type of fan writing known as slash fiction, which we will discuss in more detail later in this chapter. But what is important to note at this point is that, thanks to the internet, it is just one of the many ways media audiences create and circulate their own media content today.

From fan‐fiction websites like Fanfiction.net, which boasts “more than 87 000 stories about the boy wizard Harry Potter” alone,2 to the widely popular image‐sharing website Instagram, to the still rapidly expanding “broadcast yourself” video website YouTube, to rapidly evolving platforms such as Snapchat, media consumers are increasingly becoming media producers as well. The decentralizing power of digital technologies has shattered the conventional understanding of media audiences as “inert vessels waiting to be activated by injunctions to … consume,”3 and in the process generated a need for new ways of understanding audiences and their interactions with media. As we demonstrate in this chapter, the key to understanding much audience activity – activity that positions audiences as, at once, consumers and producers (i.e. “prosumers”4) – is pleasure. Thus, this chapter unfolds in four parts. First, we review what media scholars have had to say about pleasure, and in particular, transgressive pleasures. Second, we look at the pleasures associated with transgressive texts. Third, we consider the pleasures that arise from the transgressive practices of audiences. Finally, we conclude by reflecting on transgressive pleasure as a subject of study in the field of critical media studies.

Theories of Pleasure: An Overview

Historically, media scholars have avoided the topic of pleasure, deeming it unworthy of serious attention. On those rare occasions when they have directly addressed it, they have forcefully condemned it. Perhaps the most famous academic assault on pleasure came from the Frankfurt School scholars Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno, who in 1972 wrote, “Pleasure always means not to think about anything, to forget suffering even when it is shown. Basically it is helplessness. It is flight; not, as is asserted, flight from a wretched reality, but from the last remaining thought of resistance.”5 Nor were Horkheimer and Adorno the last media scholars to criticize pleasure so vigorously. Just 3 years later, Feminist film critic Laura Mulvey, in her famous essay, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” set out to “destroy” the pleasure afforded by Hollywood cinema.6 Initially, then, pleasure – as both an audience experience and an academic pursuit – was ignored or damned.

It was not until the 1980s – when media scholars began to attend carefully to audiences – that pleasure emerged as a subject of sustained inquiry.7 Challenging the view that pleasure is simple and uncomplicated, media critic Ien Ang argued:

Both in common sense and in more theoretical ways of thinking, entertainment is usually associated with simple, uncomplicated pleasure – hence the phrase, for example, “mere entertainment.” This is to evade the obligation to investigate which mechanisms lie at the basis of that pleasure, how that pleasure is produced and how it works – as though that pleasure were something natural and automatic. Nothing is less true, however. Any form of pleasure is constructed and functions in a specific social and historical context.8

Though the study of pleasure became increasingly common, pleasure itself continued to be disparaged. Its nearly universal condemnation was rooted in the widespread belief that “pleasures were ‘complicit’ with a dominant ideology,” and therefore, subjugation.9 More recently, however, scholars have begun to recognize that pleasure need not necessarily serve dominant or hegemonic interests, for there is more than one type of pleasure.

In his 1975 book, The Pleasure of the Text, the French semiotician Roland Barthes made an important distinction between two types of pleasure: plaisir and jouissance. While both arise out of audience–text interactions, they involve very different modes of approaching or interacting with the text and, thus, function in very different ways. For Barthes, plaisir describes a comfortable and comforting pleasure that emerges from a passive interaction with a text. Because plaisir is generated when audiences willingly submit to the structured invitations of the text, such as its narrative form (see Chapter 5), its stereotypical images (Chapter 6), or its activation of the male gaze (see Chapter 7), it works to preserve the ideological status quo, making it an essentially conservative and hegemonic pleasure. Often, plaisir is associated with the pleasure of consumption because it accepts the text on its own terms, treating it as finished and finalized, a ready‐made product to simply be consumed. As there is nothing especially creative or productive about this mode of audience–text interaction, the American media scholar John Fiske argues that the resulting pleasure, plaisir, affirms the “dominant ideology and the subjectivity it proposes.”10

In contrast to plaisir, jouissance – which is often translated into English as “bliss, ecstasy, or orgasm”11 – is an ecstatic and disruptive pleasure that emerges from an active engagement with a text. Instead of submitting to the text, audiences rework and remake it to serve their own needs and desires. Jouissance is typically associated with the pleasure of production because the interaction of audience and text creates something novel and inventive in its wake. Consequently, jouissance typically functions as a transgressive or counter‐hegemonic pleasure. Elaborating on this point, Fiske explains that jouissance involves a temporary breakdown of subjectivity, a momentary release from the social order, and an evasion of ideology.12 To further clarify the distinction between plaisir and jouissance, consider the different types of pleasures that one might derive from passively “watching” a film and actively “playing” a video game. The pleasure of the former is one of comfort and reassurance that derives from identifying with the protagonist and being led along step‐by‐step by the story. The pleasure of the latter is one of involvement and interactivity, of directing and controlling the action, of “losing oneself” in the game: “the ultimate ‘eroticism of the text’.”13

It is Barthes’ second mode of pleasure, jouissance, that concerns us most directly in this chapter. Barthes employs an array of sexual metaphors to explain jouissance, a mode of audience–text interaction other scholars have referred to as an “erotics of reading.”14 The use of the term “erotics” seems especially fitting to us, for it captures the dual character and function of jouissance: transgression and production. Consequently, we have dubbed the critical approach that animates this chapter “media erotics.” For us, media erotics reflects a concern with the sensuous, transgressive, and productive ways audiences interact with texts. Since erotics may seem like a strange descriptor to portray an approach to media, it is worth taking a closer look at its etymology. The term “erotic” derives from Eros, the Greek god of primordial lust, sublimated impulses, creative urges, and fertility. Like Eros, erotics or eroticism has two principle traits or dimensions, one involving prohibition, taboo, and transgression and the other involving expenditure, dissemination, and production.15 Thus, eroticism is at once transgressive (of the status quo or established order) and productive (of something new), which is why Eros was also known to the Greeks by the epithet Eleutherios, “The Liberator.”

But, in what contexts might interaction with media be understood as erotic or liberating, which is to say, both transgressive and productive? To answer this question, it is worthwhile to reflect on what is meant by these two concepts. Transgression refers to an action or artistic practice that breaks with the prevailing cultural codes and conventions of society (i.e. those codes and conventions that function to sustain the ideological status quo in a particular place and time). When we speak of transgression in relation to the media, many people think of high‐profile acts involving the political appropriation and alteration of media icons, such as when the British graffiti artist Banksy painted an image of a drunken Mickey Mouse fondling a scantily clad woman on a Los Angeles billboard advertisement in 2011 (Figure 12.1). But transgressive practices are typically not so public or dramatic. Audiences engage in a wide range of transgressive behaviors every day, including the practice of “oppositional reading” discussed in Chapter 10 or the writing of fan fiction like that which opens this chapter. Nor is transgression limited to political activists and media audiences. On occasion, even mainstream media texts possess transgressive or resistive elements. Indeed, as we will see shortly, certain kinds of texts possess strong transgressive potential.

Figure 12.1 Piece of street art by Banksy in Los Angeles, depicting a drunken Mickey Mouse and coked‐out Minnie Mouse partying with a skinny model on a giant billboard. The piece was named “LiViN THE DREAM,” and is located on a billboard in front of the Directors Guild of America Building on Sunset Blvd.

Source: © Ted Soqui/Corbis.

In addition to their transgressive quality, Erotic interactions with media are productive, by which we mean generative of alternative pleasures, meanings, and identities. When audiences take up media in creative, inventive, and novel ways, adapting and altering them to serve purposes other than what they were intended for, their activities – whether interpretive, participatory, or material – can be understood as productive. In contrast to consumptive practices, which involve deferring to the text and its dominant pleasures, productive practices co‐create the text, facilitating new habits of seeing, thinking, and being in the world and, by extension, counter‐pleasures that trouble and disturb the status quo. Erotic analysis provides critics with a set of critical tools for understanding the transgressive and productive practices of audiences; practices that are unique to human beings, as is evident in the difference between animal and human sexual activity. Whereas the sexual behavior of animals is purely instinctual, serving the purpose of procreation, human sexual activity is something more, involving what Georges Bataille calls “an immediate aspect of inner experience.”16 In other words, eroticism concerns subjective desires and not simply an innate urge to reproduce. It is because eroticism is unique to human sexual activity that we alone can experience shame – as well as profound enjoyment – in the transgression of taboos.17 In the next two sections, we will adopt an Erotic perspective to more fully understand both transgressive texts and the transgressive practices of audiences.

Transgressive Texts

As we have seen throughout Critical Media Studies, many of the popular media produced in the Western world work to reaffirm dominant ideologies concerning gender, race, class, and sexuality. This has to do with how the media industry is organized (Chapter 2), how media workers are professionalized (Chapter 3), and how deeply embedded cultural ideologies and psychic structures unconsciously seep into and are reproduced by media products (Chapters 6–9). But not all media products or texts – even mainstream media texts – are hegemonic, or, at least, not exclusively hegemonic. Though no media text is inherently transgressive (since what is transgressive in one context may not be in another), certain kinds of texts are more likely to function transgressively than others because of the way they engage audiences. In this section, we examine two kinds of texts with strong potential for facilitating transgression: writerly texts and carnivalesque texts.

The writerly text

In addition to his distinction between plaisir and jouissance, Roland Barthes made a crucial distinction between readerly (lisible) and writerly (scriptible) texts.18 For Barthes, the readerly text is one whose meaning is relatively clear and settled, and therefore asks very little of the audience. The readerly text is designed to be passively consumed. A classic example of a readerly text would be Steven Spielberg’s 1975 film Jaws, which is designed to elicit a precise set of emotional responses in a very particular sequence. It is difficult to watch this film and not be swept along by its story. So successful is Jaws at eliciting a particular response (fear) that many viewers are scared to swim in the ocean after seeing it. Alternatively, the writerly text is more unfinished and unsettled, and thus invites the audience to co‐create its meaning. The writerly text favors the active involvement and interpretation of the audience. In fact, if the audience fails to invest in making its own meanings and connections, then its experience of the text will likely be unfulfilling and perhaps even boring. The 2018 film The Shape of Water affords a good example of a writerly text, for it resists simple description and explanation; its meaning depends to a great extent on what audiences bring to and do with the text.

Barthes’ distinction between readerly and writerly texts closely parallels the Italian scholar Umberto Eco’s differentiation between closed and open texts. Though Barthes’ and Eco’s classifications are very similar, it is worth exploring how Eco describes his differentiation. Whereas the closed text aims “at eliciting a sort of ‘obedient’ cooperation,” the open text “not only calls for the cooperation of its own reader, but also wants this reader to make a series of interpretive choices.”19 In other words, while the closed text invites a limited and predetermined response from the audience, the open text actively involves the audience in the production of interpretation as part of its generative process.20 Adopting the language from Chapter 10 regarding polysemy, we might say that closed and open texts vary in their degree of strategic polysemy: closed texts tend to be less polysemous and open texts tend to be more polysemous. But regardless of which terminology we adopt, scholars agree that texts encourage different levels and types of audience interaction, and vary in the degree to which they constrain or empower audience interpretations. Though the writerly text can be “open” in a wide variety of ways, we wish to highlight two features common to many writerly texts: intertextuality and polyphony.

Intertextuality concerns the ways that texts gesture at or refer to other texts. In some cases, intertextual gestures are intentional, meaning that the producer of the text deliberately makes reference to another text. This mode of intertextuality might be described as strategic because it exists by design. In other cases, the reference to an outside text is initiated by an audience member rather than by the producer of the text; the gesture is unplanned and unintentional. This mode of intertextuality can be described as tactical. Tactical intertextuality could be as simple as someone being reminded of a favorite song by something they heard a character say on television, even though the character did not explicitly reference that song. The intertextual gesture in this example is initiated entirely by the audience member. We will return to tactical intertextuality later in this chapter when discussing the topic of interpretive play. But, for the moment, we are concerned with strategic or planned intertextuality, which Ott and Walter have classified into three types: parodic allusion, creative appropriation, and self‐reflexive reference.21

- Parodic allusion describes a type of intertextuality in which the primary text incorporates a caricature or parody of another text. This is a common device on television programs like The Simpsons and Norsemen, which frequently mimic or imitate well‐known scenes, plot devices, and characters from other media texts.22 Parodic allusion is commonly used for comedic effect, mocking or poking fun at the text it is mimicking.

- Creative appropriation refers to a stylistic device in which the primary text incorporates an actual portion or segment of another text. Rather than imitating or mimicking that text, creative appropriation weaves all or part of it into its very fabric. The inclusion of another text is usually done for artistic or creative reasons. The most obvious example would be hip‐hop music, which frequently samples the beats of other songs.

- Self‐reflexive reference reflects an intertextual strategy in which the primary text gestures to external discourses or events in a manner that demonstrates a self‐awareness of its own cultural status or production history. It is often the most subtle and difficult to detect of the three types of strategic intertextuality, as it relies on “insider” or fan‐based knowledge. Self‐reflexive references generally function as knowing winks or inside jokes to fans. An example would be when the dialog between two characters comments on something that recently happened in the personal life of one of the actors playing them.

This taxonomy of strategic intertextuality, while by no means comprehensive, does begin to highlight the diverse ways that texts might elicit the active participation of audiences. With all three types of intertextuality, the audience is invited to co‐create the meaning of the primary text by “opening” it to dialog with other texts. While strategic intertexuality is not inherently transgressive, it does activate a mode of audience–text interaction that, through dialog, increases the text’s “polysemic potential.”23

Whereas intertextuality places a text in dialog with other texts, polyphony places it in dialog with itself. The term polyphony, which refers to the “many‐voicedness” of a text, was coined by the Russian literary scholar Mikhail Bakhtin to explain the dialogic quality of some novels, such as those of Dostoevsky.24 A dialogic text is one that stages an unending conversation between Self and Other, and, thus, is perpetually open and unfinished. But, how is such dialog possible? Intertextuality is one answer, as we have seen, and polyphony is another. The latter has to do with the relation between the characters, narrator, and author. In a polyphonic text, the characters’ voices are autonomous, meaning that they exist on the same plane or level as the narrator and have equal authority to speak. In other words, the narrator does not speak for the characters, but to and with the characters, each of whom also has a voice and is interacting dialogically both with other characters and with themselves (i.e. internal dialog). In Bakhtin’s words, “The polyphonic novel is dialogic through and through. Dialogic relationships exist among all elements of novelistic structure … ultimately, dialogue penetrates within, into every word of the novel, making it double‐voiced.”25 Because all voices or utterances occur on an equal level, notes Sue Vice, “The polyphonic novel is a democratic one.”26 While Bakhtin’s concern was exclusively with the novel, polyphony can also be used to assess the dialogic potential of other media, such as films and massively multiplayer online games.27

The carnivalesque text

In the previous section, we explored the writerly text, a type of text that lends itself to a mode of audience–text interaction that is erotic, meaning that it is both transgressive and productive. In this section, we explore the carnivalesque text, a second type of text that is well suited to an erotic mode of audience–text interaction. Like polyphony, the notion of the carnivalesque was developed by Mikhail Bakhtin to account for a certain tendency in some literature. Writing in a repressive and suffocating political climate, much of Bakhtin’s scholarship was concerned with literary forms that challenged the hierarchies of “official” culture and disrupted the monologic (singular) voice of authority. He found one of these forms in François Rabelais’ 16th‐century novel Gargantua and Pantagruel. According to Bakhtin, Rabelais’ novel was characterized by traits common to medieval carnival. Carnival refers to the popular feasts, festivals, and revelries of the Middle Ages, though it is rooted in the Dionysian celebrations of the Greeks and the Saturnalia of the Romans. According to Bakhtin, “carnival celebrated temporary liberation from the prevailing truth and from the established order; it marked the suspension of all hierarchical rank, privileges, norms, and prohibitions … It was hostile to all that was immortalized and completed.”28 The carnivalesque, then, describes those texts that embrace and embody the spirit of medieval carnival.

For Bakhtin, carnival was dominated by two elements: folk humor, which is opposed to the serious tone and official authority of both church (ecclesiastical culture) and state (feudal culture); and laughter, which is “a special kind of universal laughter, a cosmic gaiety that is directed at everyone, including the carnival’s participants.”29 Bakhtin divided folk humor into three main forms: (1) ritual spectacles, which include carnival pageants and comic shows in the marketplace; (2) comic verbal compositions, which are typified by written and oral parodies, as well as inversions and travesties; and (3) genres of billingsgate, which involve curses, profanities, insults, and invective. Perhaps the closest thing to this kind of folk humor in contemporary society would be sporting spectacles like professional wrestling, though sketch comedy shows like Saturday Night Live and Last Week Tonight with John Oliver and daytime and late‐night talk shows like Late Night with Seth Meyers and Conan also share some common elements. Central to carnival’s three major forms is grotesque realism, an aesthetic of degradation or debasement, “the lowering of all that is high, spiritual, ideal, abstract.”30 Through grotesque imagery and language, lofty things are brought down to a material, earthly level, while lowly and less privileged things are valued and celebrated. In the remainder of this section, we explore four common and intertwined tropes used in grotesque realism: the grotesque body, abjection, uncrowning, and ambivalence.

- The grotesque body. Images of the body play a central role in the aesthetic of grotesque realism. But these images privilege a particular type of body: one that is unruly and unfinished, polluted and mutable, and disfigured and deformed; one focused on the lower bodily stratum and its excremental excesses (feces, urine, sperm, and menstrual blood). The grotesque body – in contrast to the docile and finished, sterile and settled, and refined and beautiful classical body (think of Greek marble sculptures) – is a leaky body; it concerns openings and orifices, celebrating that which is socially taboo. The grotesque body is common to the horror, slasher, and zombie film genres. But it is also featured in reality‐based television shows such as RuPaul’s Drag Race, where the dominant norms and conventions of the classical body are called into question, often in highly affirming and socially progressive ways. Though shows such as NBC’s The Biggest Loser have also featured bodies coded as grotesque, that show is not especially transgressive because it is specifically about disciplining those bodies and bringing them more in line with the ideal of the classical body.

- Abjection. In Powers of Horror, Julia Kristeva defines abjection as “what disturbs identity, system, order. What does not respect borders, positions, rules.”31 Abjection arises from the crossing of cultural boundaries and the pollution/defilement of social categories. By dividing the world into internal and external, the body establishes an ideal boundary for staging the abject. Hence, that which is discharged or expelled from the body (i.e. menstrual blood, spittle, sweat, urine, feces, mucus) evokes disgust and revolt. For some, the frequent images of and discourses about excrement on the television show South Park may give rise to the abject. Commenting on the abject in this series, Brian Ott writes, “If something can come out of or go into someone’s anus, it probably has on South Park.”32 The pleasure of abjection lies within its very transgressions, which captivate as well as revolt, attract as well as repel, fascinate as well as disgust. Abjection desires the very things it casts out. Like the compulsion to stare at a horrific traffic accident, the abject registers and appeals at an affective, bodily level.

- Uncrowning. In contradistinction to the grotesque body and abjection, which exalt that which is considered lowly and taboo, the trope of uncrowning degrades and debases that which is lofty or high. Uncrowning utilizes mockery or ridicule to bring down to earth governing figures or controlling institutions. In the process, it fosters symbolic inversion or a world‐upside‐down perspective. Uncrowning or social inversion is also a familiar trope on South Park, where adults and celebrities are frequently derided. In the episode, “Stupid Spoiled Whore Video Playset,” for instance, Paris Hilton is depicted as an unintelligent, selfish “whore.” The pleasure involved in inverting existing cultural hierarchies – of bringing adults and celebrities down to earth and elevating children as superior in insight – is carnivalesque, “for it is the pleasure of the subordinate escaping from the rules and conventions that are the agents of social control.”33 Uncrowning is also a common element in programs like Last Week Tonight, which mercilessly mock politicians and expose their human foibles.

- Ambivalence. Perhaps the most challenging of the four tropes Bakhtin associates with an aesthetic of grotesque realism is that of ambivalence. Carnivalesque texts are, for Bakhtin, inherently ambivalent because they contain contradictory feelings and impulses like fear and elation, seriousness and humor, praise and abuse, crowning and uncrowning, order and chaos, certainty and uncertainty, and familiarity and unfamiliarity. But the ambivalent dimension of the carnivalesque – and the universal laughter at its heart – fuels the very possibility of social change, for it is fundamentally dialogic in character, an exchange between Self and Other. As Shanti Elliot explains, “In the narrative, song, and ritual of many traditions [and media], ambivalence creates a flexible realm of meaning that holds socially transformative potential.”34 In the conversations they stage between high and low, life and death, carnivalesque texts generate new ways of seeing, thinking, and being in the world. And therein lies their erotic force, their capacity to combine transgression and production.

Before turning from transgressive texts to the transgressive practices of audiences, we wish to briefly reflect on how critics might utilize an Erotic perspective. One option available to the Erotic critic is to study the audience–text interaction facilitated by writerly and carnivalesque texts, assessing their capacity to elicit disruptive and productive pleasures. By examining textual traits such as intertextuality, polyphony, and grotesque realism, the critic evaluates the level and nature of audience interaction, along with the pleasures and meanings that interaction evokes.

Transgressive Practices

Just as texts vary in their degree of openness (readerly vs. writerly), audiences vary in their degree of activeness. As audience activity increases, so too does the erotic potential of the audience–text interaction. But it is important to remember that no audience activity, like no text, is inherently transgressive. What practices count as transgression always depends upon the particular social and historical context in which they occur. Moreover, audience activity can be measured and evaluated in a number of different ways. In this portion of the chapter, we will focus on three types of audience activity in particular: interpretive play, user participation and user‐created content, and fandom and cultural production.

Interpretive play

The first type of erotic activity or practice engaged in by audiences is interpretive play. By interpretive play, we mean an improvisational mode of audience–text interaction that ignores dominant interpretive codes in favor of interpretive codes that fulfill personal needs or desires. If we were to chart the interpretive activity of audiences on a continuum, it would range from highly passive (a vessel waiting to be filled with received cultural meaning) to highly active (a bricoleur who constructs his or her own meaning out of the raw semiotic materials found in texts). Interpretive play aligns with the highly active end of the continuum and may arise out of one of three interpretive practices: cruising, drifting, or skimming.

- Cruising. When audiences engage with texts, it is often for the purpose of sense‐making; they simply wish to understand what the text means and, thus, proceed to interpret signs consistent with dominant codes and conventions. But, sometimes, audiences do not care about the prescribed meaning of a text and are driven less by a desire to understand it intellectually and more by one to experience it sensually. In this context, according to Harms and Dickens, “images and communications are not rationally interpreted for their meaning, but received somatically as bodily intensities.”35 Barthes terms this interpretive practice “cruising,” adding that “the body is in a state of alert, on the lookout for its own desire.”36 As an interpretive practice, cruising is about surface rather than depth, about getting caught up in the material pleasure of sensation. If you have ever found yourself so mesmerized by the colors of a film that you stopped paying attention to its plot or dialog, you were cruising the text. “The pleasure [jouissance] of the text,” elaborates Barthes, “is that moment when my body pursues its own ideas – for my body does not have the same ideas I do.”37 Because such bodily pleasure is always singular and fleeting, it destabilizes – if only momentarily – socially constructed meanings and subjectivities.38

- Drifting. To understand the interpretive practice of drifting, it is helpful to think of the activity of reading a book. “Has it never happened, as you were reading a book,” queries Barthes, “that you kept stopping as you read, not because you weren’t interested, but because you were: because of a flow of ideas, stimuli, associations? In a word, haven’t you ever happened to read while looking up from your book?”39 Drifting involves audiences generating highly personal associations to other texts, a practice we defined earlier in this chapter as tactical intertextuality. Tactical intertextuality arises not from the text, but from the audience reading practice: drifting. Rather than following the text, the text follows the reader as she or he makes individualized connections and links. Drifting is not daydreaming; it does not arise out of boredom or a lack of interest in the text, but from a deep focus on elements within it. When one reads with this sort of intensity, one does not recognize associations so much as one creates them. When you are reading for a class and you suddenly connect that reading with some personal event or experience in your life, you are drifting.

- Skimming. A third interpretive practice that possesses erotic potential is skimming. If cruising is reading sensually and drifting is reading intertextually, then skimming is reading purposefully. It is typically undertaken with a specific aim, often to identify the main concepts or themes in a message as quickly as possible. Skimming allows the reader to form an overall impression of a text without investing the time required to attend to every word or sign. Skimming is transgressive inasmuch as it does not respect the whole, thus challenging the authority of the text’s producer to delimit its meanings. As an interpretive practice, skimming is about both surface and depth; the reader scans the surface of the text until she or he finds an important point or nugget, at which point she or he dives in, taking greater care and time to interact with the text. Skimming is an interpretive practice that nearly every college student has engaged in while cramming for a quiz or text, and one that, when performed successfully, is almost certainly a site of pleasure.

These three modes of interpretive play are neither comprehensive nor mutually exclusive. Indeed, they often work in tandem, as one can move in and out of different interpretive practices. The common link between them, as well as others we might add to the list, is the notion of play. Commenting on the importance of play in our everyday lives, Henry Bial observes:

We play to escape, to step out of everyday existence, if only for a moment, and to observe a different set of rules. We play to explore, to learn about ourselves and the world around us … [P]lay is … the force of uncertainty which counter‐balances the structure provided by ritual. Where ritual depends on repetition, play stresses innovation and creativity. Where ritual is predictable, play is contingent.40

Play, especially as children engage in it, is a highly creative and inventive activity. Objects are utilized for undesignated and illegitimate purposes (e.g. a large box becomes a fort) and rules are created, modified, and often discarded as desire dictates. Impulsive and loosely structured, children’s play models what we mean by interpretive play. To approach a media text in this fashion is to take, quoting Michel de Certeau, “neither the position of the author nor an author’s position,” but to detach it from its origin, to invent in it something different than was intended, and to create something unknown from its fragments.41

User participation and user‐created content

In addition to generating their own pleasures, meanings, and identities through interpretive play, audiences can also potentially generate erotic experiences through direct involvement in the coproduction or production of the text. Coproduction arises from user participation, by which we mean an audience–text interaction that requires the audience – through the aid of an interface device – to directly engage with the text in a manner that alters the experience of it. Digital video games are the most obvious example, but there are others. With the aid of a remote control, user participation is also possible in relation to television viewing, for instance. While most viewers watch television according to strict programming schedules, one might surf through many channels for an extended period of time without ever settling on a single program. The itinerant viewer is still having a meaningful and presumably pleasurable experience, but he or she is actively influencing the contours and texture of that experience. The activity of channel surfing, which is admittedly less common in the era of digital TV (because one need not change the channel to learn what is on other ones), generates a text unique to the individual user.

But let us return to video games, which began to garner serious academic attention in the 1980s due to interest in their interactive quality. Unlike more traditional communication technologies such as print, radio, and film, which allow for only limited user participation, digital video games require direct and frequent inputs from users. Simply put, digital games oblige users to “play” them. Recently, scholars have begun to chart the specific pleasures that users derive from playing video games.42 The three principal ones suggested by research in this arena are control, immersion, and performance.

- Control. In 1990, psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi introduced the concept of flow to describe moments of optimal experience in life.43 For Csikszentmihalyi, certain activities in life produce heightened states of enjoyment because they strike a delicate balance between being too easy (boredom) and being too difficult (anxiety). Basically, people achieve flow, an intense feeling of joy and creativity, when they feel challenged – pushed to their limits – by an activity, but not frustrated by it. Put another way, the experience of flow involves the paradox of control. One must feel that one has sufficient control to obtain an objective, but never so much that the activity stops being challenging. Digital games operate according to this same principle. They present the gamer with the experience of control (quite literally concretized through a controller or joystick) without ever ceding it completely. Digital games are designed so that the better one becomes at playing them, the more challenging the task becomes; as soon as a player masters a skill, she or he advances to the “next level.” By employing the paradox of control, digital games continuously produce extreme enjoyment.

- Immersion. Given the frustrations and burdens of everyday life, we often evince a desire to escape from the “real” world into a land of pure wish fulfillment – a fact that partially accounts for the popularity of amusement and theme parks. Because of their interactive quality, digital games are especially effective at fostering elaborately simulated places in which we can forget our troubles and lose ourselves. When one becomes fully immersed in a digital game, the external world vanishes and the distinction between game and player fades away. The combined experience of total immersion and flow is frequently described by players as being “in the zone.” If you have ever attempted to speak to a player when he or she is in the zone, you know how futile it is. Digital games are not, of course, the only media that allow for immersion. Recent research on use of MP3 players such as an iPhone, for instance, suggests that they create a sonorous envelope in which one loses one’s self in the sensorial enjoyment of music (jouissance).44 Again, this is why people listening to their iPhones in public appear to be in a different world.

- Performance. Immersion in simulated worlds allows for yet another type of pleasure, the “experimentation with alternative identities … The pleasure of leaving one’s identity behind and taking on someone else’s.”45 Digital role‐playing games (RPGs) necessitate the creation of avatars (i.e. users’ unique representations of themselves) and, thus, allow users to inhabit bodies or characters, if only virtually, and to adopt personas that may be drastically different from their non‐gaming selves.46 This type of “identity play” creates opportunities for users to escape the social structures that routinely discipline them (i.e. keep them in line) according to their gender, race, sexuality, and the way they look, sound, and dress. For some, this means not only trying out or experimenting with unfamiliar subjectivities, but also expressing actual desires and aspects of themselves that may not be accepted or acceptable in everyday life. The pleasure of performance lies in its inventive, creative, and productive character. Unlike so much of our mediated environment, which by positioning us as (passive) consumers tells us both who and how to be, RPGs foster imagination and self‐creation. We tell them who and what we want to be.

User participation is hardly limited to just video games, however, especially as new media technologies become more and more interactive. Devices such as cellphones, tablets, and other computing technologies all demand user participation. Though such devices were originally used primarily for sending and receiving messages and for storing and retrieving data, advances in wireless connectivity have created novel opportunities for interactive play and engagement. The mobile game I Like Frank, for instance, uses Global Positioning System (GPS) technology to allow players in the real city of Adelaide to interact with players in a virtual city who log in from around the world. The game, which interrogates the boundaries between “real” and “virtual” by requiring street players and online players to swap information, was created by Blast Theory, a London‐based artists’ group that mixes interactive media, art, and performance “to ask questions about the ideologies present in the information that envelops us.”47 While new media technologies increasingly require user participation, the content – be it in the form of virtual environments or of navigational maps – is still principally (though certainly not exclusively) produced and distributed by large media conglomerates. Consequently, there are definite limits to the range of meanings and pleasures users can generate. The augmented reality (AR) mobile game Pokémon GO, for instance, which was a collaboration between Niantic and Nintendo, had grossed more than $2 billion worldwide as of September 2018. And, while Pokémon GO can be immensely enjoyable, it hardly invites any kind of serious ideological critique.

In contrast to user participation, which involves the co‐creation of the text, user‐created content (UCC) places production of texts exclusively in the hands of the masses. Before looking at a few specific examples of UCC and the personal and social functions it serves, it is useful to chart its chief characteristics. A report prepared for the Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development (OECD) by Sacha Wunsch‐Vincent and Graham Vickery of the Directorate for Science, Technology and Industry identifies three central characteristics of UCC: the material must (1) be “published in some context” that is publicly available, (2) demonstrate “creative effort” through the production of original content or the sufficient adaptation of existing content, and (3) be “created outside of professional routines and practices.”48 This definition is designed to include diverse media formats (i.e. text, image, audio, video) across a variety of platforms, including personal websites, wikis (Wikipedia), podcasting, social networking sites (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Pinterest), digital video‐ (YouTube, Vimeo, Snpachat) and photo‐sharing sites (Google Images, Instagram, Imgur), digital message boards and forums, and online feedback, while excluding email, bilateral instant messages, and commercial market material. Since it is impractical to discuss all of the UCC platforms just mentioned, we have chosen to limit our discussion to blogs.

Short for “web log,” a blog is an online site maintained by an individual or group that features time‐dated postings of commentary and other material such as graphics, video, and links. Though blogs did not appear until the late 1990s, current estimates put the total number of “active” English‐language blogs at about 450 million. Blogs typically fall into one of two categories: issue‐oriented or personal diary. Issue‐oriented blogs, explains alternative media scholar Chris Atton, “democratize what has long been the providence of the accredited expert (such as the professional politician and the journalist) by enabling the ‘ordinary’ contributions of people outside the elite groups that usually form the pool for opinion and comment” on the political and social concerns of the day.49 Bloggers draw their authority not from professional credentials or expertise, but from their own personal, subjective experience with issues. Thus, they often tell stories using language and examples that relate to and resonate with their audience. Moreover, since issue‐oriented blogs are largely opinion‐driven and do not face the same organizational constraints as media institutions, they can tackle topics and issues often considered taboo in mainstream journalism.

Not surprisingly, personal diary blogs, unlike issue‐oriented blogs, tend to be about the person who writes them. In some cases, such blogs are mostly a means of promoting one’s own artistic and creative activities. Consider Jenna Mourey (a.k.a. Jenna Marbles), who, after graduating from college with a BS in psychology, began regularly vlogging (video blogging) on YouTube. As of November 2018, Jenna had 18.9 million subscribers. Jenna’s most well‐known video, “How to Trick People into Thinking You’re Good Looking,” accounts for 67 million of the almost 3 billion total views across all her videos. Similarly, Logan Paul, who dropped out of college in 2014 to pursue vlogging and social‐media entertainment fulltime, had 15.9 million followers as of January 2018. Jenna’s and Logan’s popularity, as well as that of other online celebrities, is significant, for as Atton explains, “Participatory, amateur media production contests the concentration of institutional and professional media power and challenges the media monopoly on producing symbolic forms.”50 Though Jenna’s vlogs focus on self‐promotion, some personal diary blogs focus on self‐expression through autobiographical writing. A study of an erotic story (available via the Sehakia website) by Al Kawthar, a self‐identified Muslim lesbian from Algeria, concluded that autobiographical writing can create “a space for agency within which counterhegemonic sexualities are asserted, and transgressive normative possibilities enacted.”51 These examples, though limited to blogs, reinforce previous research, which has concluded that UCC “leads to three cross‐sectional trends: increased user autonomy, increased participation, and increased diversity.”52

Fandom and cultural production

All of us are fans of something: a sports team, an actor or actress, a musical group, or perhaps, like Carrie Bradshaw, Manolo Blahnik shoes. Fans are audiences who possess a special affinity for and loyalty to a particular media or cultural text; they are, in a word, enthusiasts. One of the authors of this book is a committed fan of Fox’s So You Think You Can Dance. He views the show religiously, reads online blogs about it, cheers for his favorite dancers, analyzes it (at length) with other friends who are also fans, and occasionally goes to see the live tour. The show is, to say the least, quite meaningful to him. The other author is a diehard fan of the sandwiches made at a little shop in Boulder, Colorado, called Snarf’s. He would eat their sandwiches, which he often describes as orgasmic, every day if he could. Obviously, they are a source of great pleasure for him. These examples suggest that fans do not merely receive media texts, but rework them “into an intensely pleasurable, intensely satisfying popular culture.”53 In this section, we will examine the multitude of ways that fans actively make meanings, derive pleasures, and fashion senses of self through media.

The study of fandom – organized communities or subcultures comprising persons who share a special affinity for or attachment to a media text, which they express through their participation in communal practices (fan fiction, etc.) and events (conventions) – began in the 1980s. At that time, fans were often derided by the media and non‐fans as fanatics, obsessive nut jobs, and just plain weird. The first wave of scholars to study fandom, which included figures such as John Fiske, Henry Jenkins, Camille Bacon‐Smith, and Constance Penley, was very much interested in challenging this stereotype. For them, fandom involved interpretive communities whose creative and productive activities empowered them and challenged the hegemonic culture. Contemporary fan scholar Jonathan Gray has dubbed this period and type of scholarship “Fandom is Beautiful”54 because of its overly romantic view of fans and the counter‐hegemonic potential of fan culture. In spite of this limitation, it nevertheless established several important categories for understanding and evaluating fandom. The first generation of fan scholars recognized that what most separates fans from other audiences is the degree to which they engage in cultural production, or the generation of semiotic, enunciative, and textual materials related to a specific media artifact.55

- Semiotic productivity refers to the way fans use the semiotic (i.e. symbolic) resources in media texts to enhance the meaningfulness of their everyday lives. In Chapter 10, for instance, we discussed Janice Radway’s study of romance novels, whose female readers often select only those stories and attend to only those themes that reaffirm feelings of self‐worth.56 Similarly, in her study of online fandom surrounding television soap operas, Nancy Baym found that personalization is among the chief interpretive practices of fans:

One core practice in interpreting the soap is personalization, whereby viewers make the shows personally meaningful. They do this by putting themselves in the drama and identifying with its situations and characters. They also bring the drama into teir own lives, making sense of the story in terms of the norms by which they make sense of their own experiences. This referencing from the world of the drama to the lives of viewers is the overriding way in which viewers relate to soaps.57

Henry Jenkins, drawing upon the work of Michel de Certeau, refers to this process of selective personalization by fans as textual poaching. Based on his study of science fiction fandoms, he too argues that fans promote their own meanings over those of producers as a way of drawing texts closer to the realm of lived experience.58 Textual poaching should not be confused with Stuart Hall’s notion of oppositional decoding, explained in Chapter 10. Whereas oppositional reading adopts a reactionary stance to a text’s preferred ideology, poaching is far more fluid and arises from fans asserting interpretive authority: their own right to make textual meanings. “For the fan,” explains Jenkins, “reading becomes a kind of play, responsive only to its loosely structured rules and generating its own kind of pleasure.”59

In addition to the notion of textual poaching, Jenkins is also interested in rereading, or the fact that fans repeatedly return to the same text again and again. Once a story’s resolution is fully known, the reader no longer bears the same relation to it. Instead of being motivated by form and the desire to resolve narrative mysteries, the reader may turn his or her attention to other interests, such as specific themes and characters.60 The opportunity to focus so intensely on characters – to get to know them – allows for the development of parasocial relationships, in which fans form intimate bonds with media characters or personalities that, though inevitably one‐sided, can produce outcomes similar to actual social relationships. Rereading, then, is an intensely personal mode of textual poaching that allows fans to build (parasocial) relationships with media characters or celebrities. Though, at first glance, this behavior may seem “fanatical,” it is quite common today. Increasingly, Facebook users invite musicians, athletes, and other famous people to be their “friends.” Some users go a step further, and leave personal messages on these celebrities’ Facebook pages.

- Enunciative productivity, in contrast to the primarily internal and personal character of semiotic productivity, is public and communal. Fans are rarely fans in isolation. Rather, they discuss and debate their shared interest in a media text at length. This can occur in person (i.e. face‐to‐face) through participation in local clubs and fan conventions, or it can occur remotely (i.e. virtually) through online chatrooms, listservs, and other electronic forums. Regardless of how participants “come together,” they engage in similar (though certainly not identical) communication rituals or practices. Among the most common types of enunciative productivity or fan talk is exegesis: careful attention to textual minutiae and hyper‐detailed analysis of characters, themes, and plot developments. Close textual analysis can include a wide variety of interpretive activities, such as judging the quality or emotional realism of a text, commenting on surprising plot twists, pointing out narrative and character inconsistencies or visual continuity goofs, highlighting seemingly trivial actions or events that have deeper meaning or relevance, and speculating about what will happen next. Exegetical energy is particularly high around texts with lengthy, complex storylines such as soaps or that include mysterious, seemingly inexplicable phenomena such as Twin Peaks, Lost, and Stranger Things. Regardless of text, however, analysis is designed to demonstrate textual mastery and fan knowledge, which in an informational economy such as a fan community, translates into prestige, reputation, and, thus, influence.61

Another way fans demonstrate textual knowledge and mastery, thereby heightening their cultural capital within a fan community, is by being the first to report “insider” information such as production schedules, future narrative events or arcs (termed spoilers by fans), actor contract disputes, and the like. Fan communities are often very hierarchical, and consequently newcomers or neophytes to a particular fandom may be verbally disciplined if they fail to follow communal norms or demonstrate proper respect for fan elders. Alternatively, the newbie–elder relationship may function in a more apprentice–mentor capacity, whereby the newcomer is initiated into the community by being taught its codes and customs. In her largely auto‐ethnographic account of Star Trek fandom, Camille Bacon‐Smith discusses the relatively structured phases of initiation she underwent, including being greeted by the Star Trek Welcommittee, meeting and getting to know members personally, and learning about fan‐produced texts.

- Textual productivity, the third category of fan production, refers to the vast array of artistic, literary, educational, and entertaining cultural products that fans create. Games, character biographies, episode guides (for television shows), artwork, short films, fanzines, and fan fiction represent just a few of the products common to fandom. In many ways, the products created by fans resemble the products generated by the mainstream media, fashion, and culture industries. The principal difference is that, while media texts are produced for profit, most fan texts are produced for pleasure, albeit often at considerable effort and financial expense to the fan. Though it is tempting to consider fan‐produced media as simple, amateurish, or childish, especially since fans rarely have access to state‐of‐the‐art equipment, it can rival and even exceed mainstream media products in creativity, originality, aesthetic quality, and overall production values. In his study of online South Park fandom, for instance, Ott notes the sophistication of Babylon Park, an animated spoof that combines the elaborate storylines of Babylon 5 with the fart jokes, general character style, and stop‐motion technique of South Park.62 Ott also mentions the 3D images produced by a fan at sweeet.com, many of which are parodies of movie posters involving South Park characters (Figure 12.2). A more recent type of fan art – referred to simply as “vids” – entails the splicing together of clips from films and television shows to create video montages that tell stories which differ in theme or perspective from the original text. The fans, known as “vidders,” who produce these montages demonstrate their creative and artistic abilities through audio and video editing rather than original filmmaking. “Experienced vidders,” notes Mazar, “hold formal and informal workshops to help others learn these skills,” allowing more and more fans to become cultural producers.63

Perhaps the most studied form of fans’ textual productivity is fan fiction. Fan fiction, or fanfic for short, is a literary genre in which fans write unauthorized stories that expand upon the storyworld (characters or setting) of a mainstream media text, such as a novel, film, or television show.64 “Writing stories about characters of a favorite television program,” explains Rhiannon Bury, “is a means of extending the meanings and pleasures of the primary text.”65 Fan fiction is typically written by women and often revolves around science fiction texts such as Blake’s 7, Dr Who, Smallville, Heroes, Battlestar Galactica, and Stargate: SG‐1. Since fan fiction is not sanctioned by the companies that hold the copyrights to the media texts used as the basis for its stories, and it is commonly published online or in fan magazines, most fanfic is illegal. Despite clear copyright infringement, fan fiction tends to be ignored or at least tolerated by media companies, however. They recognize that it is produced by their most loyal fans, a group they do not want to alienate. The transgressive character of fan fiction, then, has less to do with its legal status and more to do with how it specifically functions for the fans who write it. Fans appropriate and rework media texts they love as a way of making those texts better address their own needs and social agenda.66 To illustrate this process, we briefly examine two popular subcategories of fan fiction: Mary Sue and slash.

Figure 12.2 Fan artwork: South Park movie poster parodies.

Mary Sue is a subgenre of fan fiction in which the author/fan inserts herself as a character into the storyworld of a popular media text. Such stories are referred to as “Mary Sues” because this was the name of the central female character in Paula Smith’s famous parody of the subgenre titled, “A Trekkie’s Tale.”67 Though the content of Mary Sue fan fiction is infinitely diverse, the underlying form of the stories is overwhelmingly predictable. With few exceptions, Mary Sue characters are adolescents who are either related to or romantically involved with one of the principal characters from the original media text. An author of a Mary Sue writing about the storyworld of Stargate Atlantis, for instance, might introduce a young female character who is romantically involved with Col. John Sheppard. In addition to being closely linked to one of the primary characters, Mary Sues are almost always beautiful, beloved by the other characters, and extremely intelligent. They are also central to the narrative action, and usually save the day before meeting an untimely death at the story’s end. Mary Sues are, for most fan writers, the first fan fictions they write. Because they are seen as beginning attempts at fan writing, they are widely denigrated even within the fan communities that produce them. But, nonetheless, they serve an important cultural function for the women who write them.

According to fandom scholar Camille Bacon‐Smith, Mary Sue stories are a way for their authors to confront the painful memories and experiences of adolescence, when they were teased for interests (i.e. science fiction and action adventure) and behaviors (i.e. nonseductive fashion and nonsubordinate attitudes) deemed too “masculine.” Mary Sue stories rewrite and hence recode childhood experiences by creating “perfect” female characters that are both competent and well liked, intelligent and desirable. They fulfill an emotional need for their authors by creating a cultural model of the ideal woman with which fans can identify.68 Often, as fan writers “mature,” they stop writing Mary Sues and begin writing other forms of fan fiction. One of these forms, which is generally regarded by media scholars as a far more subversive subgenre, is known as slash.

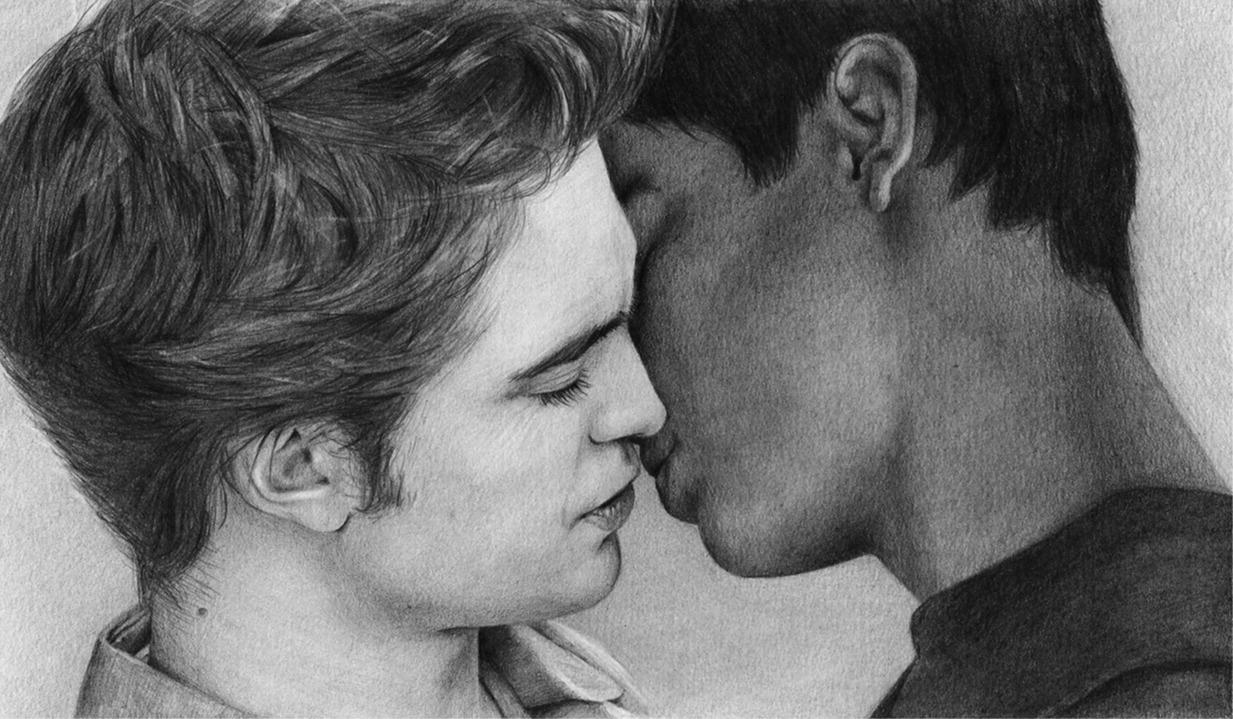

Slash, like Mary Sue fan fiction, appropriates the characters and storyworld of a popular (and, historically, often science fiction) text for personal ends. But, in contrast to Mary Sues, it does not insert the author as a character in the story. It does, however, feature two or more of the main characters from a popular media text in a romantic and often explicitly sexual relationship that they do not, in fact, have in the original (or “canon”) text. This subgenre is referred to as slash because the stories are identified by the first name or initial of each of the paired lovers, separated by a “/.” Slash fiction centers exclusively on the relationship between same‐sex (usually male) characters.69 It emerged in the 1970s, when Star Trek fans began writing erotic stories about the relationship between Captain Kirk and his first officer, Mr. Spock. Though slash fiction was dominated by Kirk/Spock stories early on, it has greatly diversified over the years. A few popular pairings today include Harry Potter and Draco Malfoy (Harry Potter), Xena and Gabrielle (Xena: Warrior Princess), Frodo Baggins and Samwise Gamgee (Lord of the Rings), and Poe and Finn (the Star Wars saga). Slash stories are commonly accompanied by fan art, such as the Edward/Jacob (Twilight) and Frodo/Sam images seen in Figures 12.3 and 12.4.

For the mostly heterosexual women who write it, slash fiction furnishes a vital outlet to envision, explore, and tell stories about romantic and sexual relationships in which the partners are powerful equals.70 It is, notes Constance Penley, “an exemplary case of female appropriation of, resistance to, and negotiation with massproduced culture.”71 In the specific case of Buffy the Vampire Slayer slash, the figure of the vampire offers an additional “vehicle through which to encode subversive pleasures of sexuality and desire.”72 Because vampires, as with the central characters in many other science fiction texts, are not quite human, slash writers have even more freedom to “imagine something akin to the liberating transgression of gender hierarchy John Stoltenberg describes: a refusal of fixed‐object choices in favor of a fluidity of erotic identification.”73 In other words, fan fiction is not simply about producing alternative meanings and interpretations; it is also about experimenting with and producing alternative identities, about exploring the limits of who one is and what one can become.

Figure 12.3 Fan artwork: Slash image of Edward and Jacob, from the Twilight series. Randy Owen, Edward and Jacob, 2009. Graphite on paper, 7” × 12” (17.8 cm × 30.5 cm), private collection. (https://www.facebook.com/randyowencreations).

Source: Randy Owen.

Figure 12.4 Fan artwork: Slash image of Frodo and Sam, from The Lord of the Rings.

Source: © Solarfall.

Reflections on Transgression

The study of pleasure and transgression, and their intersection, is extraordinarily challenging. Since the experience of pleasure is intensely personal, it is difficult to measure and quantify. Despite this difficulty, critics operating from an Erotic perspective can investigate both (1) particular kinds of texts and the pleasures they afford and (2) the interpretive, participatory, and material practices of audiences and the pleasures associated with them. But, even if a critic is able to isolate the pleasures in audience–text interactions, the question arises whether or not those pleasures function transgressively and productively. In other words, what difference do they make in the world? Though a comprehensive answer to this question is beyond the scope of this chapter, we would like to briefly reflect on the relationship between transgression and social change. Transgression is one form of social resistance; other forms include subversion, disruption, and rebellion.74 But, in contrast to these forms, which are either collective or coordinated, transgression is individual and improvisational. Transgression is not undertaken with the intent of bringing about social change.

That transgression is not strategically designed to promote social change does not mean that it cannot contribute to such change, however. Over time, many individual transgressive acts can accumulate and have an aggregative effect. So, while an isolated act of transgression may seem innocuous and insignificant, numerous such acts can, collectively, participate in processes of social change. Hence, critics should be careful not to judge the character and significance of transgressive texts or practices according to their immediate social effects. It is far more important to study how transgressive texts and practices are personally productive, how they allow audiences to invent their own meanings, pleasures, and identities, and how they contribute, in the words of Michel de Certeau, to “making do” in a world where most media are created for corporate profit, not social benefit.75 Further, because its effects are cumulative, transgression rarely results in rapid social change. Unlike rebellion, which brings about social change suddenly and often violently, transgression promotes change incrementally, remaking social norms and conventions slowly and subtly.

While transgression can and does participate in processes of social change, then, students need to be cautious about its uncritical celebration. There is a propensity to romanticize the role of transgressive texts and practices in society, thereby underestimating hegemony and its capacity to coopt and commodify transgression and to re‐interpellate subjects. There is also a tendency, after studying the topic of media erotics, to see transgression in everything; such a move greatly weakens the force of the concept, along with the transformative potential it holds. So, the key to studying media erotics involves striking a careful balance between appreciating the transgressive pleasures of audiences and recognizing their contextual character.

Conclusion

This chapter approached media from the newly emerging and still developing perspective of media erotics, a perspective that seeks to understand the counter‐hegemonic pleasures (both transgressive and productive) made possible by some audience–text interactions. The chapter began by charting two kinds of texts –writerly and carnivalesque – that possess qualities with strong potential for generating erotic pleasures. It then turned to the transgressive practices of audiences, highlighting how interpretive play, user participation and user‐created content, and fandom and cultural production all hold out the promise of erotic pleasure. The final portion of the chapter situated the study of transgression within the topic of cultural resistance more broadly, showing how transgression may contribute to broader cultural change, but also cautioning students about romanticizing transgressive pleasures.

SUGGESTED READING

- Bacon‐Smith, C. Enterprising Women: Television Fandom and the Creation of Popular Myth. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1992.

- Bakhtin, M. Rabelais and His World, trans. H. Iswolsky. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1984.

- Barthes, R. The Pleasure of the Text, trans. R. Miller. New York: Hill and Wang, 1975.

- Bataille, G. Erotism: Death and Sensuality, trans. M. Dalwood. San Francisco, CA: City Lights Books, 1962.

- Bonstetter, B.E. and Ott, B.L. (Re)Writing Mary Sue: Écriture Féminine and the Performance of Subjectivity. Text and Performance Quarterly 2011, 31, 342–67.

- Brooker, W. Using the Force: Creativity, Community and Star Wars Fans. New York: Continuum, 2002.

- Butler, C. The Pleasures of the Experimental Text. In Criticism and Critical Theory, J. Hawthorn (ed.), pp. 129–39. London: Edward Arnold, 1984.

- de Certeau, M. The Practice of Everyday Life, trans. S. Rendall. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1984.

- Dhaenens, F., Van Bauwel, S., and Biltereyst, D. Slashing the Fiction of Queer Theory: Slash Fiction, Queer Reading, and Transgressing the Boundaries of Screen Studies, Representations, and Audiences. Journal of Communication Inquiry 2008, 32, 335–47.

- Fiske, J. Understanding Popular Culture. Boston, MA: Unwin Hyman, 1989.

- Gray, J., Sandvoss, C., and Harrington, C.L. (eds.) Fandom: Identities and Communities in a Mediated World. New York: New York University Press, 2007.

- Hills, M. Fan Cultures. New York: Routledge, 2002.

- Jenkins, H. Textual Poachers: Television Fans & Participatory Culture. New York: Routledge, 1992.

- Jenkins, H. Fans, Bloggers and Gamers: Exploring Participatory Culture. New York: New York University Press, 2006.

- Johnston, B., and Mackey‐Kallis, S. Myth, Fan Culture, and the Popular Appeal of Liminality in the Music of U2: A Love Story. Landham: Lexington Books, 2019.

- Keft‐Kennedy, V. Fantasising Masculinity in Buffyverse Slash Fiction: Sexuality, Violence, and the Vampire. Nordic Journal of English Studies 2008, 7, 49–80.

- Kerr, A., Kücklich, J., and Brereton, P. New Media – New Pleasures? International Journal of Cultural Studies 2006, 9, 63–82.

- Kristeva, J. Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, trans. L.S. Roudiez. New York: Columbia University Press, 1982.

- Lewis, L.A. (ed.) The Adoring Audience: Fan Culture and Popular Media. New York: Routledge, 1992.

- O’Connor, B. and Klaus, E. Pleasure and Meaningful Discourse: An Overview of Research Ideas. International Journal of Cultural Studies 2000, 3, 369–87.

- Ott, B.L. (Re)Locating Pleasure in Media Studies: Toward an Erotics of Reading. Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies 2004, 1, 194–212.

- Ott, B.L. Television as Lover, Part I: Writing Dirty Theory. Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies 2007, 7, 26–47.

- Ott, B.L. Television as Lover, Part II: Doing Auto[Erotic]Ethnography. Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies 2007, 7, 294–307.

- Ott, B.L. The Pleasures of South Park (An Experiment in Media Erotics). In Taking South Park Seriously, J. Weinstock (ed.), pp. 39–58. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2008.

- Scodari, C. Resistance Re‐examined: Gender, Fan Practices, and Science Fiction Television. Popular Communication 2003, 1, 111–30.

- Stallybrass, P. and White, A. The Politics and Poetics of Transgression. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1986.

- Stam, R. Subversive Pleasure: Bakhtin, Cultural Criticism, and Film. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989.

- Taylor, T.L. Multiple Pleasures: Women and Online Gaming. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 2003, 9, 21–46.

- Vice, S. Introducing Bakhtin. New York: Manchester University Press, 1997.

NOTES

- 1 This is a brief excerpt from a Sherlock‐inspired slash (John Watson/Sherlock Holmes) story. heresyourstupidjohnlock, The Taming of John Watson, FanFiction.net. https://www.fanfiction.net/s/9032528/1/The‐Taming‐of‐John‐Watson (accessed November 30, 2018).

- 2 R. Mazar, Slash Fiction/Fanfiction, in The International Handbook of Virtual Learning Environments, J. Weiss, J. Hunsinger, J. Nolan, and P.P. Trifonas (eds.) (Dordrecht: Springer, 2006), 1141.

- 3 A. Ruddock, Media Audiences 2.0? Binge Drinking and Why Audiences Still Matter, Sociology Compass 2008, 2, 8.

- 4 A. Toffler, The Third Wave (New York: William Morrow and Company, 1980), 282–305.

- 5 M. Horkheimer and T.W. Adorno, Dialectic of Enlightenment, trans. J. Cumming (New York: Continuum, 2001), 144. Originally published by Querido of Amsterdam in 1947, the first English translation did not appear until 1972.

- 6 L. Mulvey, Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, in Feminism and Film Theory, C. Penley (ed.) (New York: Routledge, 1988), 59. This essay was originally published in the autumn 1975 issue of the film journal Screen.

- 7 B. O’Connor and E. Klaus, Pleasure and Meaningful Discourse: An Overview of Research Ideas, International Journal of Cultural Studies 2000, 3, 370.

- 8 I. Ang, Watching Dallas: Soap Opera and the Melodramatic Imagination (New York: Routledge, 1985), 19.

- 9 O’Connor and Klaus, 375.

- 10 J. Fiske, Understanding Popular Culture (Boston, MA: Unwin Hyman, 1989), 54.

- 11 Fiske, Understanding, 50.

- 12 Fiske, Understanding, 50–1.

- 13 J. Fiske, Reading the Popular (New York: Routledge, 1989), 93.

- 14 R. Barthes, The Grain of the Voice: Interviews 1962–1980, trans. L. Coverdale (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press), 175; B.L. Ott, (Re)Locating Pleasure in Media Studies: Toward an Erotics of Reading, Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies 2004, 1, 194–212.

- 15 G. Mayné, Eroticism in Georges Bataille and Henry Miller (Birmingham, AL: Summa Publications 1993), 13.

- 16 G. Bataille, Erotism: Death and Sensuality (San Francisco, CA: City Lights Books, 1962), 29.

- 17 Bataille, 29–31; see also Mayné, 3.

- 18 R. Barthes, S/Z: An Essay, trans. R. Miller (New York: Hill and Wang, 1974), 5.

- 19 U. Eco, The Role of the Reader: Explorations in the Semiotics of Texts (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1979), 7, 4.

- 20 B.L. Ott, Television as Lover, Part I: Writing Dirty Theory, Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies 2007, 7, 29.

- 21 B. Ott and C. Walter, Intertextuality: Interpretive Practice and Textual Strategy, Critical Studies in Media Communication 2000, 17, 435.

- 22 H. Gray, Watching with The Simpsons: Television, Parody, and Intertextuality (New York: Routledge, 2006).

- 23 J. Fiske, Television Culture, 2nd edn (New York: Routledge), 128.

- 24 M. Holquist, Dialogism: Bakhtin and His World, 2nd edn (New York: Routledge, 2002), 33–4.

- 25 M. Bakhtin, Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics, trans. C. Emerson (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1984), 40.

- 26 S. Vice, Introducing Bakhtin (New York: Manchester University Press, 1997), 112.

- 27 M. Flanagan, Bakhtin and the Movies: New Ways of Understanding Hollywood Film (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009); R. Stam, Bakhtin, Polyphony, and Ethnic/Racial Representation, in Unspeakable Images: Ethnicity and American Cinema, L.D. Friedman (ed.) (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1991), 251–76.

- 28 M. Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World, trans. H. Iswolsky (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press), 10.

- 29 R. Stam, Subversive Pleasures: Bakhtin, Cultural Criticism, and Film (Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989), 87.

- 30 Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World, 19.

- 31 J. Kristeva, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, trans. L.S. Roudiez (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982), 4.

- 32 B.L. Ott, The Pleasures of South Park (An Experiment in Media Erotics), in Taking South Park Seriously , J. Weinstock (ed.) (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2008), 41.

- 33 J. Fiske, Television Culture (London: Methuen, 1987), 243.

- 34 S. Elliot, Carnival and Dialogue in Bakhtin’s Poetics of Folklore, Folklore Forum 1999, 30, 129.

- 35 J.B. Harms and D.R. Dickens, Postmodern Media Studies: Analysis or Symptom?, Critical Studies in Mass Communication 13, 1996, 222.

- 36 Barthes, The Grain of the Voice, 231.

- 37 R. Barthes, The Pleasure of the Text, trans. R. Miller (New York: Hill and Wang, 1975), 17.

- 38 Fiske, Understanding, 51.

- 39 R. Barthes, The Rustle of Language, trans. R. Howard (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1989), 29.

- 40 H. Bial, Play, in The Performance Studies Reader, H. Bial (ed.) (New York: Routledge, 2004), 115.

- 41 M. de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life, trans. S. Rendall (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1984), 169.

- 42 A. Kerr, J. Kucklich, and P. Brereton, New Media – New Pleasures?, International Journal of Cultural Studies 2006, 9, 63–82.

- 43 M. Csikszentmihalyi, Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience (New York: Harper & Row, 1990).

- 44 J. Gunn and M.M. Hall, Stick it in Your Ear: The Psychodynamics of iPod Enjoyment, Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies 2008, 5, 135–57.

- 45 Kerr et al., 74.

- 46 T.L. Taylor, Multiple Pleasures: Women and Online Gaming, Convergence 2003, 9, 26; see also S. Turkle, Life on Screen: Identity in the Age of the Internet (New York: Touchstone, 1995), 177–96.

- 47 Blast Theory, About Blast Theory, https://www.blasttheory.co.uk/about‐us/ (accessed December 14, 2008).

- 48 Working Party on the Information Economy, Participative Web: User‐Created Content (Paris: Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development, 2007), 8, http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/57/14/38393115.pdf (accessed December 14, 2008).

- 49 C. Atton, Current Issues in Alternative Media Research, Sociology Compass 2007, 7, 21; see also H. Hewitt, Blog: Understanding the Information Reformation That’s Changing Your World (Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson, 2005), 71.

- 50 Atton, 21.

- 51 N. Zukic, Webbing Sexual/Textual Agency in Autobiographical Narratives of Pleasure, Text and Performance Quarterly 2008, 28, 397.

- 52 Working Party on the Information Economy, 35.

- 53 J. Fiske, The Cultural Economy of Fandom, in The Adoring Audience: Fan Culture and Popular Media, L.A. Lewis (ed.) (New York: Routledge, 1992), 30.

- 54 J. Gray (ed.), Fandom: Identities and Communities in a Mediated World (New York: New York University Press, 2007), 1.

- 55 Fiske, The Cultural Economy of Fandom, 37.

- 56 J.A. Radway, Reading the Romance: Women, Patriarchy, and Popular Literature (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1984), 184.

- 57 N.K. Baym, Tune In, Log On: Soaps, Fandom, and Online Community (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications), 71.

- 58 H. Jenkins, Textual Poachers: Television Fans & Participatory Culture (New York: Routledge, 1992), 18, 34, 53.

- 59 H. Jenkins, Star Trek Rerun, Reread, Rewritten, in Fans, Bloggers, Gamers: Exploring Participatory Culture (New York: New York University Press, 2006), 39.

- 60 Jenkins, Textual Poachers, 67.