6

Cultural Analysis

Few songs in recent memory have garnered as much critical response as “This Is America,” a mid‐2018 single by the filmmaker, actor, and musician Donald Glover. The music video for the song is a kaleidoscope of enigmatic images, with early frames of joyous dancing quickly giving way to a shocking scene of violence: Glover shooting a hooded figure in the back of the head at point‐blank range with a handgun. From this point on, the video confronts viewers with an increasingly disturbing set of behaviors, most notably a moment where Glover slaughters an entire church choir with an assault rifle. The lyrics, set to a thunderous backbeat, address the prevalence of guns and materialism within communities of color. Popular online reaction to the viral song and video was swift, but mixed.1 Some lauded the production for drawing attention to issues of racism, police brutality, and mass shootings, and especially to the ways that entertainment venues present these issues with techniques that dull audience outrage. Others accused Glover of producing veritable propaganda against the Second Amendment’s right to bear arms, and of drawing unwarranted attention to negative elements in America rather than accenting positive developments. A few even worried that the popularity of the song/video might encourage individuals to glorify the kind of violence that it appears to criticize.

Behind each of these reactions to “This Is America” lies a basic assumption: the song’s portrayal of political and social issues will shape the way that its audiences perceive these issues in the larger world. In many ways, these worries lend credence to the work of scholars who take a cultural or ideological approach to media texts. Scholars in this strand of media studies seek to understand how media texts influence the way we think about the world as political and social beings. Currently described by the scholarly umbrella term Cultural studies, cultural and ideological critics claim that media texts like television shows and newspapers, far from merely reflecting the world around us, always represent a skewed or partial vision of society in relation to class, race, gender, sexuality, age, disability, and a host of other social constructs. In essence, media texts tend to represent particular perspectives on the world and society at the cost of excluding other views, and the worldviews represented in the media are often those of socially powerful or privileged groups.

This chapter begins with a discussion over theories of culture and ideology, concentrating on how the ideologies of any given culture work to normalize and privilege certain perspectives on reality. We then briefly outline the historical development of the British Cultural studies tradition as a way of understanding the political underpinnings of Cultural studies scholarship. Finally, we consider how ideologies influence the construction of media texts in relation to two historically relevant social issues in the Cultural studies tradition: class and race.

Cultural Theory: An Overview

As a way of understanding social organization, “culture” can be a problematic term. Scholars disagree over the best way to conceptualize or understand the issue of culture. In mulling over the idea of culture, sociologist Michael Richardson provides this possible definition: “Culture is simply what human beings produce and the means by which we preserve what we have produced.”2 This definition provides a good foundation for understanding culture (that it is constructed, multifaceted, and uniquely human). In formulating a specific definition of culture, however, it is helpful to consider the key ingredients or aspects that make a culture known. The “building blocks” of culture fall into physical, social, and attitudinal forms:

- The first form of culture is physical. Picture a society thousands of years in the future attempting to study and gain knowledge about our current culture. How might its scholars understand us better? The most obvious way would be through the physical objects that we leave behind for them to find, which are called artifacts. Artifacts are any of the material aspects of daily life that possess widely shared meanings and manifest group (national, social, political) identification to us. Artifacts include clothing, music, television shows, automobiles, computers, comic books, billboards, carnival rides, space shuttles, and more. Virtually any manufactured item that you can point to (including this textbook) is an example of an artifact. An artifact is a material, human‐made object of a culture.

- The next form of culture is social. After collecting and analyzing our artifacts, the futuristic scholars studying us will attempt to decipher the social codes and rules that governed the creation of those artifacts. They will attempt to reconstruct the practices or customs of our daily lives, the habitual performances of our particular social conventions. If they found this textbook, for example, they might assume that reading, learning, and critiquing were all social practices of ancient American culture. Similarly, they might formulate some ideas about our hygienic customs if they were to discover any one of the wide assortment of tools related to personal upkeep: toothbrushes, blow dryers, contact lens cases, and so forth. If artifacts are the products of our shared lives, then customs are our shared, lived experiences: eating, working, dancing, mourning, sex, exercise regimens, driving laws, birthday traditions, and so on.

- The final form of culture is attitudinal. Our customs, laws, and traditions reflect particular ways of understanding the world. To continue with our futuristic society example, scholars of the next millennium might piece together enough artifacts to discover that we as Americans tended to support the notion of free speech or the concepts of individualism and personal responsibility. They might find documents with the acronym PLUR, describing the beliefs and attitudes expressed by members of modern rave culture: Peace, Love, Unity, and Respect. In essence, attitudes display the overarching ways a particular culture makes sense of the world and itself, including values, tastes, concepts of right and wrong, religious systems, economic beliefs, and political philosophies.

Now that we have some understanding regarding what constitutes culture, we can begin to pick out some of the common qualities that define it. First, culture is collective. While individuals may be a part of a particular culture, they can never inhabit a culture on their own. Culture must be shared among a group of people. It is important to remember, however, that a cultural group in itself may be as large as a nation or as small as the fandom of a syndicated television show. Computer hackers constitute a distinct cultural group, as only individuals who participate in hacking know about the artifacts, practices, and attitudes that make up the distinct culture of hackers. Therefore, while culture must be shared among a group of people, it also by definition does not include everyone. Society is always a collection of cultures and co‐ or subcultures (cultural groups that exist within larger cultural groups), and most individuals will likely be members of multiple cultural groups at one time.

Second, culture is rhetorical. It functions symbolically (see Chapter 4). Possessing culture is not natural or inherent to our biology as human beings, but rather a result of our shared symbol systems, which allow us to communicate meaning to one another. This means that a culture is sustained and transmitted exclusively through the words and images that carry significance for its members. The artifacts of a particular culture only have significance because members of the culture can name them, and the customs or attitudes of a cultural group can only be meaningful because they can be described as such. The academic report card, for instance, is a powerful artifact in American education, but its power stems from the rhetorical or symbolic aspect of our national culture. There is nothing intrinsically powerful or threatening about a piece of paper with markings on it, and there is nothing that requires an A to mean “outstanding” and an F to mean “failure.” Instead, we as a culture have symbolically and rhetorically agreed upon the meaning and power of the report card.

Third, culture is historical. It changes, evolves, mutates, fades, and even disappears over time. Like almost everything else, culture is subject to the whims and shifts of history. Some cultures have existed for millennia in different forms (Greco‐Roman culture, Jewish culture, etc.), and some appear and vanish in a matter of years. A good example of this type of sudden cultural ascent and decline is the Club Kids phenomenon of the 1980s and ‘90s. The Club Kids were a subculture within the New York party and nightlife scene. They dressed in wildly outrageous and androgynous costumes, experimented with a number of drugs, and promoted hedonistic philosophies of life. Though at times club owners paid the group to show up and promote specific venues, they were really a culture unto themselves, oftentimes throwing spontaneous parties in public places throughout New York. The Club Kids culture began to decline in the 1990s, and they are all but non‐existent today. They stand as a stark example of how cultures can suddenly form and dissipate depending on the historical moment.

Finally, and perhaps most important to our present discussion, culture is ideological. The cultures we inhabit teach us to see the world in some ways and not in others. The attitudes, practices, and artifacts of our everyday lives encourage us as individuals to interpret the world according to certain frameworks of culturally based knowledge. French discourse scholar Michel Foucault provides a stark example of how culture functions to direct our attention in his work on madness.3 The majority of cultures in Renaissance Europe did not perceive madness as problematic. It existed as a constant in daily life, a factor as unpreventable and prevalent as death. Foucault cites various historical examples and texts, including celebratory “Feasts of Fools” and the works of Shakespeare, to show how madness was intrinsically woven into the cultural fabric of the time. The 17th century, conversely, witnessed the rise of sanitariums and other confinement houses in Europe, and these institutions were primarily responsible for removing certain individuals from everyday life: the poor, the indecent, and especially the mad. The common denominator among all of these groups was their inability to contribute to the newly emerging process of economic production and consumption. Thus, the widespread “lock up” of these individuals “concerns not the relations between madness and illness, but the relations between society and itself, between society and what it recognized and did not recognize in the behavior of individuals.”4 We can see from Foucault’s discussion of madness how the structure of a culture always directs its inhabitants to perceive the world in a particular way. Though there is always room for individual interpretation, ideology is a powerful and distinct element of interpretation in every culture.

Overall, culture can be described as the collection of artifacts, practices, and beliefs of a particular group of people at a particular historical moment, supported by symbolic systems and directed by ideology. This understanding of culture in general, and ideology in particular, is important for media scholars who understand mass media texts like magazines or news programs as central components in the dissemination of a given culture’s ideologies. Scholars operating from a cultural vantage analyze media texts to understand the ideologies that inform their creation, and they seek to conceptualize how the attitudes and beliefs of a given culture find their way into the media we consume every day. Before turning our attention to the specific work of ideological media analysis, however, it is important that we have a better understanding of the role and scope of ideology in contemporary society.

The Functions of Ideology

We know from the opening section that cultures give rise to ideologies and that ideologies influence how individual members of the culture see the world, but we still need to understand the subtle ways that ideology accomplishes this directed attention. Remember, an ideology is a system of ideas that unconsciously shapes and constrains both our beliefs and our behaviors. The way that we unconsciously define the world around us, the explanations about the world that we take for granted, and the unquestioned beliefs that we hold are all the result in some way of our cultural ideologies. The four ways that ideology structures our social world are through limitation, normalization, privileging, and interpellation.

First, a given ideology limits the range of acceptable ideas that a person may consider within a particular cultural context. It promotes and legitimates certain perspectives and values while obscuring or delegitimizing others. This “blinding” function is easy to spot in certain ideologies when the interpretations that they promote are regularly identified as biased or one‐sided. Republicans and Democrats, for example, both possess ideologies that are made highly visible by the existence of the other party. Each party nevertheless functions as a culture with particular artifacts, customs, and attitudes, providing its members with an ideology that limits interpretation and helps them distinguish between right and wrong, true and false, and good and bad.

Some ideologies, however, limit our interpretation of the world in a more unconscious fashion, and we enact or support them often without realizing it. These are ideologies that have become so engrained in our minds and everyday lived experiences that we fail to notice their influence as “ideological” and accept them instead as uncontestable truth. A good example of this kind of unconscious ideology concerns human reproduction. If you ask an average group of individuals to describe the process of biological fertilization, they will likely provide you with some variation of the following narrative: Millions of sperm swim vigorously toward a passively waiting egg, each competing against all of the others to reach this prized destination first. Of those that eventually make it, only one will manage to assault the egg’s tough outer shell in order to deposit its precious genetic material inside.5 But the actual biology of this process, as cultural anthropologist Emily Martin points out, is quite different from the common account.6 In fact, the whipping tail movements of sperm do much more to propel the gametes sideways than forward, which means that they spend most of their time evading rather than invading whatever they encounter. To offset this inherent elusiveness (which would seem to impede rather than facilitate fertilization), the egg features protruding molecules on its surface that fit precisely with receptive structures on the sperm. The egg effectively “hooks” an evasive sperm with these protrusions and chemically binds it to its surface so that fertilization can begin. From a biological vantage, then, the egg is much more active in the process of fertilization than the common account allows, but Martin concludes that the account persists because it aligns with gender norms that associate activity with masculinity and passivity with femininity (see Chapter 8 for further discussion of this dynamic). She suggests in brief that ideologies of gender limit an accurate understanding of biological characteristics within the scientific community, and this initial limitation forms the basis of a widely circulated but inaccurate narrative that further blinds the wider population.

By limiting the possible perceptions or interpretations of the world, ideology also normalizes certain aspects of it. This process of defining normalcy is especially important in the realm of social relations. Ideology often makes arbitrary social relations between individuals seem natural, and it makes established relationships of power appear to be the natural order of things. For example, you are probably reading this chapter right now because your instructor assigned it as homework. Your resulting responsibility as a student is to read the chapter and absorb the information for class discussion or tests. Have you ever stopped to question where this student/teacher relationship comes from? Why does the teacher have more authority than you do in your own education? The social roles that we occupy throughout our lifetime, like child, student, and employee, place us into relationships of unequal power as a result of ideological value hierarchies. All social relations are inherently relations of power because all social relations exist in a web of ideologies that award power to certain roles over others. Your instructor has power, or “the ability to control events and meanings,”7 only because American ideology often awards authority to highly educated experts in a given field.

The distribution of power in accordance with ideology extends well beyond the college classroom. The economic ideology of capitalism, for example, ensures that employers have power over their employees, and this relationship between owner and worker seems to be a natural part of everyday life instead of a culturally constructed system. In some cultures, older individuals wield a great deal of power as revered elders, but in American society elderly individuals are often thought of (and therefore treated) as helpless, feeble, or “a drain on the system.” Power, then, is inextricably tied up with the ideological constructs of a particular culture. At times, relationships of power can be beneficial (after all, you are receiving an education, even if your instructor has the power), but they are never natural. Ideology normalizes these relationships of power and the control that they extend over individuals.

This unequal distribution of power between social actors explains one of the most important aspects of ideology: ideology privileges some interests over others. In the process of normalizing relations of power, it also informally confirms that the perspectives, qualities, and needs of socially powerful groups are more important or valid than those of socially dominated groups. The capitalist economic and ideological structure of American business culture is full of examples of this distinction. Though employees tend to do much of the actual work in a capitalist business, it is the more socially powerful managers and owners who reap most of the profits. Likewise, most businesses in America favor managerial styles that emphasize masculine qualities like assertiveness, independence, and competitiveness, a quality that helps men move up in a company and often creates difficult situations for women seeking promotion. Beyond business culture, it is also possible to see power and privilege at work in relation to the issue of marriage. As a result of different arrangements of religious and/or political ideologies, the institution of marriage in many countries outside of Europe and the Americas generally reflects the needs and interests of (socially powerful) heterosexual couples to the detriment of (socially subordinate) homosexual couples.

It may seem at this point that ideology permeates every aspect of a culture, fashioning the limits of knowledge and influencing power structures at every level of social organization. This seemingly overarching quality of ideology is central to Louis Althusser’s concept of interpellation, the fourth function of ideology. Althusser was an Algerian Marxist who was interested in the ways that ideology controls individuals. He claimed that ideology is so infused into the social structure that it actually serves as the force to interpellate us, or the force that calls us into existence as social subjects.8 Far from being unique or original, individuals are actually a collection of different ideological systems fused into one identity through the process of “hailing.” Hailing occurs when individuals recognize and respond to an encountered ideology and allow it to represent them. Althusser also suggested that because culture and ideology necessarily pre‐date the individual, individuals are “always already interpellated.”

In order to make the process of interpellation clearer, consider the following question: At what point did you begin to identify as a member of the college or university that you attend? Chances are that before you ever consciously took up that identity, the people around you had already given you objects, surrounded you with colors, or interacted with you in ways that communicated the norms or limits of that identity to you. Each of these moments constituted a hailing, or a moment of exchange where you recognized the existence of a way of understanding yourself and responded to it, allowing it to define or constitute you in the process. The process of forming identity is a process of ideological recognition. For Althusser, ideologies exhibit the range of possible identity expressions, and individuals are a collection of the ideologies to which they consciously or unconsciously ascribe. Ideological discourse not only speaks to us, it also creates the us.

Althusser’s assertion that individuals are caught in a web of ideologies from which they draw their individual identities is an interesting perspective on the role of ideology in society, but it also importantly confirms the existence of multiple ideologies circulating through a wider culture. Remember, ideology is an aspect of every culture, and even relatively small subcultures can have powerful ideologies (one only needs to look at historical cults like Heaven’s Gate or Jonestown to confirm this point). It should also be clear, however, that not all ideologies carry the same weight on a widespread scale, and we can see that some are more present than others in the minds of most people. The aforementioned concepts of social power and privilege hint at the reason for this imbalance, but something else explains the supremacy of certain ideologies in a culture over others. It is to these ideas that we turn our attention now.

Ideological Processes: Myth, Doxa, and Hegemony

A number of theories explain how certain ideologies within a culture become widespread, common, or dominant. This section will focus on three interrelated concepts: Roland Barthes’ myth, Pierre Bourdieu’s doxa, and Antonio Gramsci’s hegemony. Though myth and doxa both shed light on how ideology works, hegemony has gained a certain theoretical dominance within the field of ideological analysis. As a result, the majority of this section will focus on ideas surrounding hegemony, and hegemony will be a central theme throughout the rest of the chapter.

In his book Mythologies, Barthes outlines a theory of ideological dominance based on the notion of myth.9 A myth is a sacred story or “type of speech” that reaffirms and reproduces ideology in relation to an object. Mythologies itself is a collection of essays in which Barthes identifies a variety of cultural objects (toys, soap advertisements, etc.) and investigates them for their mythological components, or the “higher” levels of meaning that augment their basic meanings. At some basic level, for example, the video game The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim just means “a video game named The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim,” but a mythic analysis would investigate the game’s larger, culturally connoted meanings. In addition to signifying “video game,” Skyrim also relates the classic story of a hero undertaking a prophesied journey to slay a great evil (a dragon, in this case). This mythological or “higher‐level” meaning of the game connotes ideas of bravery and heroism that are central to American ideological formations, and the game in turn reinforces these ideologies by casting the mythological content as innocent and “natural.” Barthes claims that cultural myths typically normalize the ideologies of the ruling or socially privileged groups and reinforce power differentials between classes.

Another useful concept for exploring the workings of ideology is doxa. According to Bourdieu, doxa represents knowledge “which is beyond question and which each agent tacitly accords by the mere fact of acting in accord with social convention.”10 In other words, doxa refers to any constructed aspects of a culture that its members do not significantly challenge or critically reflect upon. A good synonym for doxa is “common sense.” Like myth, doxa supports certain ideologies over others by making them seem natural or simply “the way things are.” Like Barthes, Bourdieu views doxa as intrinsically tied to the ideologies of socially dominant groups. Those with social power wish to preserve the cultural doxa, while those without power seek to resist or alter it.

Figure 6.1 Bourdieu’s doxa, orthodoxy, and heterodoxy.

It is important to realize that expressing a minority opinion is not the same as resisting the “commonsense” ideologies present in doxa, for in many ways doxa is outside the realm of opinion altogether (see Figure 6.1). Consider the process of watching a popular movie at a theater with your friends. The members of your group might disagree over the relative merit of the film, but none of you would be likely to question why you had to pay to see it in the first place. The discussion between your friends over their opinion of the film is a part of what Bourdieu calls “the universe of discourse,” made up of all of the issues that may be formally agreed upon (othrodoxy) or debated (heterodoxy) in a given society. The process of handing your money over to the theater to gain admittance, however, is a part of the doxa, or “the universe of undiscussed,” made up of social rules and processes that go unnoticed and unquestioned. Paying to see a film supports capitalist ideology and reaffirms its “commonsense” validity in our cultural context.

Though myth and doxa both lend valuable insight into why certain ideologies are more widespread than others, the concept of hegemony is especially important because it helps account for the evolution of dominant ideologies. First proposed by Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci in the 1920s and ‘30s, the concept of hegemony is key in understanding the ascension and persistence of dominant ideologies. Hegemony is the process by which one ideology subverts other, competing ideologies and gains cultural dominance through the won consent of the governed (or dominated). Gramsci developed his theory of hegemony to address some of the shortcomings of Marxism. Recall the basic structure of Marxist theory from Chapter 2. Marx believed that ideology was a byproduct of a culture’s economic system, a reflection of bourgeois interests used to trick the working class into a false consciousness. He asserted that, over time, the large working class would recognize this ideological trick and overthrow the relatively small owning class. When this revolution did not in fact occur, Gramsci proposed his theory of hegemony as an explanation for its absence.

An essential function of hegemony involves convincing people to support the existence of a social system that does not support them in return. Marginalized groups do not often protest or revolt against ideologies that overwhelmingly support privileged groups because, on some level, they consent to being dominated. This statement prompts an immediate question: Why would anyone consent to such an arrangement? While dominant ideologies may reflect the desires and interests of socially powerful groups, for these ideologies to remain dominant (or hegemonic), they must also feature an additional promise: it is in the best interest of marginalized groups to accept these beliefs as well. Put another way, members of socially powerful groups act to have their worldview accepted as the universal way of thinking, and members outside of these groups come to accept some of these ideologies because they appear beneficial in some way. Gramsci refers to this process as one of “‘spontaneous’ consent” because it is typically informal or unnoticed.11

The best way to understand the spontaneous consent of hegemony is through an example. A number of ideological components within American higher education are not in the best interests of students. One dominant belief, for instance, suggests that college students should pay for their own education, a norm that does not benefit them financially as individuals. Another widespread belief suggests that instructors have the right to influence public perception of students’ intellectual ability in the form of assigned grades, a norm that certainly does not benefit most of them socially as individuals. Despite these factors, students still dutifully fork over thousands of dollars in tuition each semester and show up to class with the hopes of getting an A. Why? They consent to these beliefs because other aspects of this belief system promise that it is ultimately in their best interest to do so. Securing a college degree in many ways promises a higher professional pay grade. A system of letter grades promises social prestige to those who achieve high marks. Though presidents, deans, and professors will probably gain more financial and social rewards from the norms of this system than any individual undergraduate, the “spontaneous” consent of the student body ensures that the ideology survives as the norm.

When such consent fails, however, the concept of hegemony also explains how dominant ideologies evolve to contain this failure through a process of flexible appropriation. In such a situation, it is likely that dominant cultural institutions will absorb any challenging beliefs, integrate them into the hegemonic matrix, and re‐establish the previous norm. A number of classic studies in the field provide examples of this process. In Subculture: The Meaning of Style, for instance, Dick Hebdige looks at the subculture of British punks in the 1980s.12 The punk movement’s emphasis on anarchy and gratification represented a challenge to the hegemonic British ideologies of governance and order. As the punk movement increased in popularity and visibility, it became more of a threat to the traditional, ideological British “way of life.” In order to circumvent this threat, dominant institutions in Britain began to absorb punk life into the existing system of hegemonic beliefs. Retail shops began to sell punk clothing, and newspapers began running stories on punks and their families. By integrating the punk movement into dominant economic and cultural systems, the British hegemonic structures sanitized it and greatly diminished its challenge. “Punk” was, in a sense, absorbed and put in the service of hegemonic ideologies of capitalism and family.

As a result of this function, hegemonic systems never go away; they simply change form through a process of constant give and take between social groups. John Fiske’s discussion of jeans is a good example of the regular back‐and‐forth struggle that characterizes hegemony.13 Wearing blue jeans in the 1960s was a sign of opposition to the dominant American culture. As the popularity of such resistance began to take hold, however, retailers responded by creating an elaborate system of different mass‐produced styles and designer labels for jeans. Jeans became mainstream and normal. In response, many individuals began to rip and intentionally disfigure their jeans in an attempt to distinguish themselves from the newly established normalcy. Retailers in turn began to fade and destroy their jeans on a large scale. In this way, hegemonic ideological structures maintain control in part through the never‐ending process of integration and appropriation of marginalized ideologies.

Overall, the concepts of myth, doxa, and hegemony explain a great deal about the ideologies and power structures of a given culture. Myth is the preservation of ideology through the active retelling of dominant cultural stories. Doxa is the preservation of ideology through silence and maintaining the distinction between what can and cannot be debated. Hegemony is the preservation of ideology through won consent and flexible adaptation toward resistance. For media scholars interested in issues of culture, the concept of ideology helps to explain the structures and themes of a culture’s media texts, and the concept of hegemony helps to explain the presence of certain ideologies over others. Scholars do this type of media analysis under the academic banner of Cultural studies, an umbrella term for a wide variety of scholarship concerned with culture, ideology, privilege, and oppression. The Cultural studies tradition is relatively new in comparison to other media studies approaches, and it represents an important area in the contemporary discipline of media studies.

Cultural Studies: History, Theory, and Methodology

In a sense, the academic discipline of Cultural studies has two histories. The actual or literal discipline can be traced to 1964, with the founding of the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies at the University of Birmingham in the United Kingdom. The theoretical or conceptual history, however, actually begins in the early 20th century. The formation of Cultural studies as a scholarly perspective was in many ways a response to previous conceptions of “culture” as the exclusive realm of the upper class. Based on the works of literary/cultural critics like Matthew Arnold and F.R. Leavis, many academics in Britain at this time limited the definition of “culture” to the best aesthetic products and traditions of contemporary society. In essence, artistic products like operas, high art, and literary classics could be considered culture within this framework; horse races, quilted blankets, and cartoons could not.

Leavis endorsed literature as an especially important aspect of culture because he believed that great literary works preserved essential moral qualities of a bygone era in British history. Popular fiction, as his wife and fellow scholar Q.D. Leavis characterized it, was “not only formed to convey merely crude states of mind but it [was] destructive of any fineness.”14 From the Leavises’ perspective, it was the duty of intellectuals and academics to uphold the legacy of “cultured” literature in order to maintain moral standards in an increasingly industrialized, mediated society like Britain in the 1920s and ‘30s. Thus, we can see that defining culture was more than an arbitrary distinction of aesthetics for these thinkers; it was also a political attempt to combat the perceived ills of increased exposure to a popular mediated system that engaged “the unruly desires and immorality of the masses.”15

Reflecting on this academic movement (widely referred to as Leavisism), we can see that it clearly drew elitist distinctions between culture and mass society along class lines. “Culture” here referred exclusively to the aesthetic forms most accessible to educated or wealthy individuals, while “mass society” referred to the activities and products of the lower or working classes. This division held academic sway until the publication of Richard Hoggart’s The Uses of Literacy in 1958, which disrupted the link between the notion of “culture” and upper‐class pursuits.16 Drawing on his personal experiences as a youth in the British working class, Hoggart outlines a detailed account of working‐class culture and its norms in relation to family relationships, neighborhood structures, religious belief, and more. In this way, Uses departs from Leavisism by making a claim for the importance of working‐class cultural norms, pointing out that issues of morality are not exclusive to the upper class. The second half of the book, however, engages in a decidedly Leavisist criticism of mass culture like popular music and “sex‐and‐violence novels,” which Hoggart sees as a threat to the working‐class way of life. In retrospect, while Hoggart’s work importantly expanded ideas of morality to working‐class culture, it also continued the Leavisist tradition by affirming the perceived dangers of popular culture.

Though Hoggart began to break the notion of culture free from its Leavisist roots, the most important scholar in laying the theoretical groundwork for the distinct discipline of Cultural studies was Raymond Williams. The publication of his book The Long Revolution in 1961 marked an important turn in the academic understanding of culture. In it, Williams recognized the importance of viewing culture from ideal (Leavisist) and documentary (anthropological) standpoints, but he also proposed a third, social definition: “Culture is a description of a particular way of life, which expresses certain meanings and values not only in art and learning but also in institutions and ordinary behavior.”17 For Williams, no analysis of culture was complete without looking at all three of these dimensions. Moreover, this newly proposed social definition extended the idea of culture to include virtually all aspects of contemporary society, considering both high art and pop art, literature and comics to be important expressions of a particular culture at a particular moment in history. Williams also claimed that every culture is governed by a structure of feeling. A structure of feeling is the sum of the subtle and nuanced aspects of a historical culture, those aspects not obviously or completely captured in the artifacts of a society. Williams claimed that the contours of this structure become most apparent in intergenerational social exchanges or discussions about one’s own culture with members of another one. In many ways, the structure of feeling is intimately related to the aforementioned concepts of myth, doxa, and hegemony.

In expanding the notion of culture to include aspects of everyday pursuits, Williams opened the door for the academic study of mass‐culture products and institutions. A few years after the publication of The Long Revolution, a collective of British academics established the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies to study popular culture with special focus on ideological components of the mass media. Stuart Hall, who served as the head of the Centre from 1969 to 1979, wrote an essay entitled “Cultural Studies: Two Paradigms” in 1980 that many consider to be a crucial outlining of the institutionalized Cultural studies approach.18 The two paradigms indicated in his title are culturalism (work in the tradition of Hoggart and Williams that scrutinizes particular beliefs and activities of individuals in a given culture) and structuralism (work derived from Marx and anthropologist Claude Lévi‐Strauss that looks at how social systems limit the activities of individuals through ideology). Hall claimed that contemporary Cultural studies brings together the best aspects of each tradition, and that the traditions “pose, together, the problems consequent on trying to think both the specificity of different practices and the forms of the articulated unity they constitute.”19

Hall appears to give a balanced approach to both paradigms on the surface of the essay, but some scholars point out that his true scholarly commitments lie more closely with the structuralist focus on ideology.20 Thus, though the culturalist focus on the meanings made by particular individuals within a culture importantly paved the way for Cultural studies’ attention to popular texts, the structuralist concepts of ideology, power, privilege, and oppression have become the primary theoretical hallmarks of the contemporary Cultural studies approach. The culturalist focus has been largely absorbed into an approach based on the ethnographic study of audiences, addressed in Chapter 10 of this book.

This structuralist lens has shaped the Cultural studies discipline across five methodological motifs. First, Cultural studies is interdisciplinary. As a method of textual criticism, it appropriates and combines theoretical tools from many different fields to assemble a new approach specifically designed to address the text in question. Second, Cultural studies is pragmatic. The ideal criticism of texts from a Cultural studies perspective should be practical in nature, aimed toward a specific end, and understandable to a wide variety of people. This practicality is closely related to the third aspect of Cultural studies: it is political. Cultural studies scholarship seeks not only to identify particular ideologies, but also to challenge and alter their effects on systems of social inequality. Fourth, Cultural studies is reflexive. Cultural studies scholars adopt a critical awareness of their own social locations and the implications of that positioning. In other words, work within Cultural studies is often hyper‐aware of its own socio‐political biases, and scholars often acknowledge these limitations within their writing. Finally, Cultural studies is culturally and historically contingent. Textual criticism from this perspective is always tied to particular social systems at particular moments in time. Henry Jenkins, Tara McPherson, and Jane Shattuc refer to this dual quality as Cultural studies’ commitment to “contextualism” and “situationalism,” respectively.21

With these five themes as a guiding framework, the remainder of this chapter will look at ideologies of class and race in American media, in order to provide an in‐depth understanding of the type of work that constitutes a Cultural studies approach. This decision is purposeful. Issues of class were intimately involved in the historical evolution of British Cultural studies (both in the gradual displacement of “culture” from the upper class and in the Marxist underpinnings of structuralism), and notions of race provided an early and important historical focus to the budding discipline. It is important to keep in mind, however, that issues of ideology and power are applicable to the investigation of any social construct in a text: class, race, gender, age, sexuality, disability, and so on. To extend the same amount of attention to each of these is beyond the scope of an introductory chapter to Cultural studies, but we address the relationship to power of some of them in Chapters 8 and 9.

Ideology and Media Representations of Class

Cultural studies scholars interested in ideological issues of class look at the ways in which popular media texts communicate, justify, and maintain disproportionate socio‐economic status divisions. They also do the reverse, utilizing notions of class to understand the particular structures and effects of media texts. Overall, these scholars analyze the interplay between popular media texts and hegemonic ideologies of class that convince individuals that capitalism and class standing are “natural” forms of social existence.

Social class basically refers to the division of society into the “haves” and the “have‐nots.” You may already be familiar with many of the more specific ways to discuss class, including the divisions of upper, middle, and lower class, hybrids like upper middle class, and even phrases like “working class” or “working poor.” Marx, the pre‐eminent theorist of social class, originally divided capitalist society into three major classes: the bourgeoisie, or large‐business owners who control the means of production; the proletariat, or blue‐collar workers who sell their labor to the owners; and the petite bourgeoisie, or small‐business owners and white‐collar professionals (doctors, lawyers, etc.) who represent a minority middle class. However, he also envisioned that capitalist societies evolve according to changing social relations. As such, what we now have in American society is a class system reminiscent of Marx’s original divisions with two important differences.

The first difference is in the size of the petite bourgeoisie. Unlike in Marx’s time, when the petite bourgeoisie or middle class encompassed a relatively small number of professionals, the middle class now represents a sizeable class division in American society. This growth of the middle class (and relative shrinking of the upper bourgeoisie and lower proletariat classes) is intrinsically tied to the second important deviation from Marx: the rise of information‐ and media‐based occupations in the 20th century. As computers and technology industries have increased in scope and popularity in the last 50 years, the demand for knowledge‐based positions like technicians and programmers has increased as well. This signifies a shift away from a Marxist economy focused on material production toward one focused on mediated information dissemination. Such a shift has influenced class distinctions in a number of ways. Newly created white‐collar jobs have increased the size of the middle class, and ownership has become increasingly focused on the cultural production of lifestyles and leisure. As you might guess from the ideas discussed thus far in this chapter, the production of culture in these media industries also means the production and reification of ideologies.

Media outlets like television, film, and newspapers consistently impart two important understandings of class in America. On one hand, the American public is bombarded with images that communicate clear class distinctions. Many programs on the Bravo television network, for example, including Million Dollar Listing, Below Deck, Southern Charm, and the various Real Housewives incarnations, introduce viewers to the worlds of wealthy and famous Americans. These shows reveal a sharp disparity between the lifestyles of their economically advantaged subjects and the experiences of their largely middle‐ to lower‐class audiences. On the other hand, the media also regularly suggest that these class distinctions are permeable. Some of the appeal of these programs may be attributed to the fact that certain stars, including Charleston lawyer Craig Conover and New York real‐estate agent Luis Ortiz, appear to have overcome their middle‐ to lower‐class backgrounds to join the ranks of the economically elite. Films like The Pursuit of Happyness (2006), The Social Network (2010), and The Founder (2016) also champion the idea that one can transcend class distinctions under the right circumstances.

Two ideologies of class, in turn, help explain the presence of these messages in American media. The first is the American Dream, or the idea that a person’s level of success is directly related to the amount of effort or drive that he or she puts forth in attaining his or her goal. The American Dream is one of the most prevalent hegemonic ideologies in American media texts. There is large‐scale consent to the American Dream because it presents people with a definite avenue toward success and happiness. It boils down all of the complications of modern life into a simple equation (hard work equals success), and it symbolically erases real issues of social inequality, class struggle, profit‐motive, and so on that may function as barriers toward success. In reality, adhering to the American Dream probably does more to transform individuals into compliant workers for capitalist owners than it does to actually elevate their personal socio‐economic statuses, but this fact is difficult to see because of hegemonic qualities that veil the interests of the upper class inherent to the ideology. In addition, the repetition of the American Dream over and over in media texts like The Pursuit of Happyness and The Social Network helps to solidify it as truth in the popular consciousness.

One of the more celebrated media images in the ideological web of the American Dream is the token. A token is an exception to a social rule that affirms the correctness of an ideology. In this case, a token is an individual who has actually fulfilled the promise of the Dream and moved into the upper class based on personal initiative. Though they are exceptions rather than the norm, tokens often gain high visibility within the media because they lend a sense of legitimacy to the ideology of the American Dream. “If I can succeed,” the token says, “then anyone can.” Oprah Winfrey and Bill Gates are good examples of tokens regularly discussed in the media: both built vast empires of wealth from fairly meager economic beginnings. Of course, media outlets do not also address the millions of other individuals who never transcend their class despite their personal effort and hard work. In this way, highly visible media tokens symbolically erase the presence of systemic realities that arise from class ideologies.

Of course, the American Dream is not beyond reproach. Even within mainstream media, we have films like I, Tonya (2017) that scathingly critique the ideology. Therefore, there must be other ideologies of class that function to maintain the status quo. The second important ideology to understand in relation to the mass media is Thorstein Veblen’s idea of conspicuous consumption.22 Conspicuous consumption is the belief that one can attain membership in the “upper class” through the purchase of material goods and services. When people refer to houses as status symbols or express a need to “keep up with the Joneses,” they are hinting at this belief. People often consent to the doctrine of conspicuous consumption because it allows them to feel as if they have succeeded in life as a result of owning nice objects. In truth, individuals who believe that they have “made it” because of their consumption practices often move only slightly up the scale of the large American middle class. While their lifestyles may appear luxurious compared to viewers’ own, for example, most of the individuals featured in The Real Housewives series are really members of the upper middle class. As such, the ideology of conspicuous consumption works hegemonically to blind the majority of Americans from realizing what real upper‐class wealth actually looks like. This concealment in turn works to solidify class distinctions.

Media advertising thrives on the notion of conspicuous consumption and is a primary support system for this ideology. In her book Born to Buy, Juliet B. Schor claims that Americans are becoming the target of advertising at increasingly younger ages. “Children,” she writes, “have become conduits from the consumer marketplace into the household, the link between advertisers and the family purse.”23 Advertising literally does the work of conspicuous consumption. Its duty is to manufacture desires for products and services within the general public under the guise of consumer choice. Largely as a result of multi‐billion‐dollar advertising companies, then, ideas of conspicuous consumption are deeply ingrained into the American public from birth and register as the natural or normal consequence of competition and taste.

In sum, the dual ideologies of the American Dream and conspicuous consumption work via media texts to solidify current class divisions in America even while such divisions appear to be outdated or permeable. In 2016, according to CNN, the richest 1 percent of families controlled 38.6 percent of the total wealth in the United States, with the next 9 percent controlling another 38.6 percent. That means that the bottom 90 percent of families held just 22.8 percent of the total wealth, down from 33 percent in 1989 when the Federal Reserve began tracking these data.24 Figure 6.2, which reports even more recent data, shows that the richest 10 percent of families control 76.7 percent of the total wealth in the United States and the bottom 60 percent control only 3 percent of the total wealth. The disparity in America reflects similar trends on an international scale. In 2017, for example, the anti‐poverty organization Oxfam International concluded that the eight richest men in the world collectively held as much wealth as the poorest half of humanity (approximately 3.6 billion people).25 All together, these figures suggest that significant economic disparity is increasing in America and around the world even as ideological structures regularly appear to confirm the opposite. Class is not the only issue of privilege that continues to operate in this way, however. Another hotly contested area that often appears to be a non‐issue as a result of ideological intervention is race.

Figure 6.2 Wealth distribution in the United States, 2017.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Distribution_of_Wealth_in_the_United_States.svg (accessed November 27, 2018).

Media, Ideology, and Representations of Race and Ethnicity

Cultural studies scholars interested in media representations of race investigate how a culture’s racial ideologies help determine the structure of popular media texts like television shows, films, music, and periodicals. They analyze these texts to understand how the media reinforce cultural and ideological power hierarchies, systems that usually award privilege and power to white individuals at the expense of non‐white individuals. These scholars are especially interested in how media texts reflect hegemonic racial ideologies, concentrating on the ways these texts invite consumers to accept whiteness as the norm in relation to issues of race.

Thomas K. Nakayama and Robert L. Krizek refer to discourses of whiteness in America as “strategic rhetoric.”26 In essence, the images and words most commonly used to discuss whiteness reinforce its privileged place at the center of our understanding of race. Through media representations, social organizations, and even everyday objects, “white” becomes an overarching norm, a privileged non‐race against which all other races are measured and compared. Robert Jensen outlines a variety of ways this privilege manifested almost invisibly in his own life growing up in America: “I grew up in fertile farm country taken by force from non‐white indigenous people. I was educated in a well‐funded, virtually all white public school system in which I learned that white people like me made this country great. There I also was taught a variety of skills, including how to take standardized tests written by and for white people like me.”27

Scholarship regarding the media representation of race is vast, but work within this area can be summarized into a group of key concepts that explain how media texts operate across ideological lines within the context of American culture. These concepts are exclusion, whitewashing, stereotyping, assimilation, and othering.

Exclusion

Ironically, a prevalent representation of race in American media is actually better characterized as an absence of representation. Exclusion is the process by which various cultural groups are symbolically annihilated, or “written out of history,” through under‐representation in the media. If the media were an actual reflection of race in American culture, then one would expect to see a clear ratio between the size of a racial population in real life and its visible population in television or films. Research in this area, however, points out that the relationship between population and mainstream media visibility is highly skewed. Put bluntly, racial minorities simply do not “exist” in much of the media that we consume every day, and this absence reinforces ideological power structures by over‐representing the dominant white group in media texts.

We can see the process of racial exclusion if we compare the Latino population in America to its representation in mainstream American media. Latinos are the largest ethnic minority population in the United States, numbering an estimated 58.9 million in 2017, or 18.1 percent of the total population.28 To get an idea about how large this number really is, consider the fact that there are far more Latinos in the United States than there are Canadians in Canada. If you were to take the entire US Latino population and transform it into a Latin American country, it would have the third largest population by comparison. And yet, despite the obviously large numbers of Latino individuals living in the United States, images of the lives and issues of Latin American people are largely absent from mainstream US media. The next time that you turn on your television or access your favorite streaming service, try and find a program that centers on a Latin American family or social group. You may stumble across Jane the Virgin, East Los High, or One Day at a Time, but there is a much stronger possibility that you will discover a litany of shows depicting (largely) white American social groups like Speechless, Will & Grace, The Big Bang Theory, or Fuller House. Beyond Magnum P.I., Superstore, and Charmed, few primetime network programs feature a Latino character in a lead role. Likewise, many of the more popular or critically recognized films about Latinos since 2000, such as Y Tu Mamá También (2001), Frida (2002), The Motorcycle Diaries (2004), The Orphanage (2007), Biuitiful (2010), and Viva (2015), are either produced by foreign film companies or largely focused on the lives of Latinos outside of the United States.

Systems of symbolic exclusion do not completely remove a Latino presence from American media (as many television shows and films feature Latinos as friends, neighbors, coworkers, or other minor characters), but they do manage to erase in part the perspectives, interests, and needs of the significant US Latino population from the everyday American consciousness. On a broader scale, the exclusion of many non‐white populations from this popular consciousness necessarily reinforces ideological systems of white privilege that construct whiteness as prevalent, multifaceted, normal, and desirable.

Whitewashing

A second practice closely related to exclusion in terms of representing race in American media is whitewashing, where white actors assume roles or characters more traditionally associated with racial minorities. Whitewashing generally occurs when adapting an established property to a new medium, and it typically assumes one of two major forms. The first involves a white actor simulating a non‐white character through costume, mannerism, or speech. The history of American popular media is littered with cringeworthy examples of this simulation, with perhaps the most famous being the depiction of Chinese‐Hawaiian detective Charlie Chan by three different white actors in more than 40 films during the 20th century. Many viewers today acknowledge that such racial masquerade is in poor taste, but the practice nevertheless crops up from time to time in contemporary texts as well. Johnny Depp’s portrayal of the Native American sidekick Tonto in the 2013 film version of The Lone Ranger is a notable recent example.

The second, more common form of whitewashing involves the transformation of non‐white characters within a given source text into white characters in an adapted text. Sometimes, this transformation is blatant. Though the Ancient One in the Doctor Strange series of comics is almost uniformly depicted as a wise Tibetan man, the 2016 film adaptation features the character instead as a Celtic woman played by white actress Tilda Swinton. At other times, the transformation can involve subtler shifts in character and storyline. In adapting the popular manga series Ghost in the Shell for a 2017 film of the same name, producers cast actress Scarlett Johansson as the Japanese cyborg protagonist but altered the character’s name from “Major Motoko Kusanagi” to “Major Mira Killian” and made it explicit within the narrative that Kusanagi’s consciousness has been downloaded into Killian’s (now white) body.

Whitewashing bolsters ideological systems of white privilege by situating white actors and characters as more attractive and bankable than their non‐white counterparts. It is a particularly problematic practice because it gestures toward the importance of diverse racial representation (by drawing attention to properties that feature ethnic minorities) even as it undercuts such diversity in actual production. This paradox helps explain the simultaneous condemnation and acceptance that often accompanies the practice in the mainstream media. Though white director Ben Affleck attracted significant criticism for casting himself to play Latino CIA agent Tony Mendez in the 2012 film Argo, for example, the film also won the Academy Award for Best Picture that year, suggesting that many in Hollywood ultimately had little problem with the racial switch.29

Stereotyping

When people of color do appear in the media, they often fall victim to a third major form of racial representation. Stereotyping is the process of constructing misleading and reductionist representations of a minority racial group, often wholly defining members of the group by a small number of characteristics (see also Chapter 8 for an extensive discussion of stereotyping). Media stereotypes by definition make value judgments about the worth, taste, and morality of another culture, and in doing so they can influence our attitudes, behaviors, and actions toward members of that culture. Racial stereotypes are not always a negative reflection of a culture (the stereotype of the “smart Asian” is a good example of a positive stereotype), but all stereotypes overlook the inherent complexity of a racial group and present media consumers with simplistic and flawed representations. These simplified racial caricatures enable systems of white privilege by presenting consumers with a world where the majority of complex, interesting, and realistic characters are white.

One example of a long‐standing racial stereotype in US media is that of people of Middle Eastern descent as violent or barbaric terrorists. Even before September 11, 2001, the image of the “Arab terrorist” was prevalent in American films, such as Back to the Future (1985), True Lies (1994), The Siege (1998), and Rules of Engagement (2000). Films that reference the World Trade Center bombing like United 93 (2006) and Zero Dark Thirty (2012) naturally resonate with this stereotype, but it endures elsewhere in films like Vantage Point (2008) and London Has Fallen (2016). When the media are not depicting Middle Easterners as terrorists, other common stereotypes include shady, big‐nosed, and often irate individuals who wear turbans and ride camels (Aladdin, 1992), drive taxis (You Don’t Mess with the Zohan, 2008), or own convenience stores (Four Brothers, 2005). The repetition and combination of these stereotypical images over time reduces the complex variability of Middle Eastern peoples to a few exaggerated, stock representations. Like the process of exclusion, stereotyping establishes the hegemonic norm of whiteness by largely reducing realistic or affirming images of racial minorities, thereby erasing an accurate presence of them from the minds of many consumers.

The matter of racial stereotyping in the media is a sensitive and delicate one because it raises questions of both perception and intent. Consider, for example, the April 2008 cover of Vogue magazine, shot by renowned photographer Annie Leibovitz, which features an image of NBA sensation LeBron James clutching Brazilian supermodel Gisele Bündchen. The cover – the first to feature an African American man in the magazine’s history – quickly ignited a critical firestorm in the blogosphere.30 For many, it resembled images of “King Kong,” casting James as the dangerous (black) gorilla and Bündchen as the helpless (white) damsel.31 This interpretation was dismissed by Vogue spokesperson Patrick O’Connell, who claimed the image simply “sought to celebrate two superstars at the top of their game.”32 Though the magazine’s editors almost certainly did not perceive (let alone intend) the image to be racially insensitive, it nevertheless elicited strong condemnation from those who believed it tapped (even if only unconsciously) into decades‐old racial stereotypes of the “black brute” and “white damsel.” In support of this claim, the image is frequently juxtaposed with the World War I anti‐German recruiting poster shown in Figure 6.3. What we hope this example illustrates is that media executives and editors – even those who have the best of intentions – must be vigilantly on guard against the reproduction of racial stereotypes.

Assimilation

The comparatively small number of media texts that do focus extensively on the lives or experiences of people of color often display a fourth type of racial representation. Assimilation is the process by which media texts represent minority racial groups in a positive light while simultaneously dehistoricizing them or stripping them of their cultural identities. These groups are often shown to possess equal or better socio‐economic standings than their white counterparts, but issues of past or continued political struggle for that equality are virtually absent. Instead, racial minorities become assimilated into a middle or upper class that largely reflects the perspectives of white individuals. Except for the possibility of a “very special episode” about racism here and there, most of the problems that concern assimilated individuals involve family troubles, occupational issues, and romantic pursuits, not the issues of social power and oppression that often inform the lives of racial minorities in the real world. In this way, structures of inequality are hidden behind an apparent “face” of diversity in these texts.

Figure 6.3 World War I US Army recruiting poster.

Source: Ann Ronan Picture Library/hip/TopFoto.

The quintessential example of a racially assimilating media text is The Cosby Show. The Emmy Award‐winning show follows the antics and trials of the Huxtables, an African American, upper‐middle‐class family led by parents Cliff (Bill Cosby) and Clair (Phylicia Rashad). Cliff is an obstetrician and Clair is a successful attorney, and the family overall represents middle‐class achievement and the possibilities of social mobility for racial minorities. In line with the American Dream, The Cosby Show suggests that success is open to all who are talented and hard‐working if only they educate and apply themselves. Consequently, the show’s viewers may come to think that widespread African American poverty is a result of individual weakness or cultural deficiency, instead of systemic and ideological oppression. Shows like Cosby and The Jeffersons paved the way for other successful African American television shows that displayed tendencies toward assimilation, including Family Matters and The Fresh Prince of Bel‐Air. Compared to the popular 1970s show Good Times, which chronicled the life of an African American family in the face of poverty, unemployment, and other social troubles often tied to racial power, these later shows virtually ignored issues of political struggle and assimilated their African American characters.

Like the American Dream, issues of racial assimilation are closely tied to tokenism. A token here is a character or personality of color whose presence in the media supposedly proves that systemic racism and white privilege no longer exist. The logic is that by consciously injecting a single racial minority into an otherwise “white” program, the program is fairly representing that minority perspective. In reality, tokens are a surface‐level concession to diversity because the token often displays elements of assimilation. Lucas Sinclair, one of the main characters in Netflix’s nostalgic science fiction series Stranger Things, is a good example of a racial token. Lucas is the only major African American character on the program in the first two seasons and practically the only person of color in the town where he lives, but the assumed effects of this extreme dissimilarity never materialize during his adventures. The implicit message here is that the monstrous “Demogorgon” represents a far greater menace to Lucas than racial inequality (which, of course, was not actually the case for African Americans in the 1980s). Media tokenism is present outside of fictional programs as well, especially in local news teams, often made up of one reporter from each major ethnic group that predominates in the area. In a satirical jab at this practice, South Park creators Matt Stone and Trey Parker have even named the only African American child in their titular Colorado town “Token Black.”

Assimilation and tokenism support ideological systems of white privilege by constructing middle‐class life and norms as implicitly white. Characters and personalities of color assimilated into the white, middle‐class media landscape seem to testify to the non‐existence of racial ideological power, obscuring real issues of racial dominance and privilege by presenting consumers with images of false diversity. This functions as a tool of hegemony, convincing people to support mainstream media representations because they seem to present a racially equitable world even as the images reinforce current racial power relations.

Othering

The final type of media representation builds from this relationship between “normal” and “white.” Othering is the process of marginalizing minorities by defining them in relationship to the (white) majority, which functions as the norm or the natural order. The understanding of “white” as a non‐race addressed at the beginning of this section is both cause and consequence of othering practices. Examples of othering within the media are often difficult to identify because they rely on the unquestioned ideological assumptions about race and culture that we use to make sense of the world. Harry M. Benshoff and Sean Griffin point out that othering was evident in the predominant practice in early Hollywood of having actors of color play a variety of ethnic characters: “African Americans and Latinos were often hired to play Native American characters, and Hispanic, Italian and Jewish actors played everything from Eskimos to Swedes.”33 This process drew clear distinctions between white and non‐white actors, privileging the unique qualities of the former and erasing the individuality of the latter. Though this may seem like an outdated practice, instances of othering still exist in the entertainment industry today. It is common, for example, to run across descriptions of Eddie Murphy, Wanda Sykes, or Tracy Morgan that characterize them as “black comedians,” but it is unlikely that one would ever encounter material describing Jeff Dunham or Amy Schumer as “white comedians.” A generic “comedian” is assumed to be white unless he or she is specified to be otherwise.

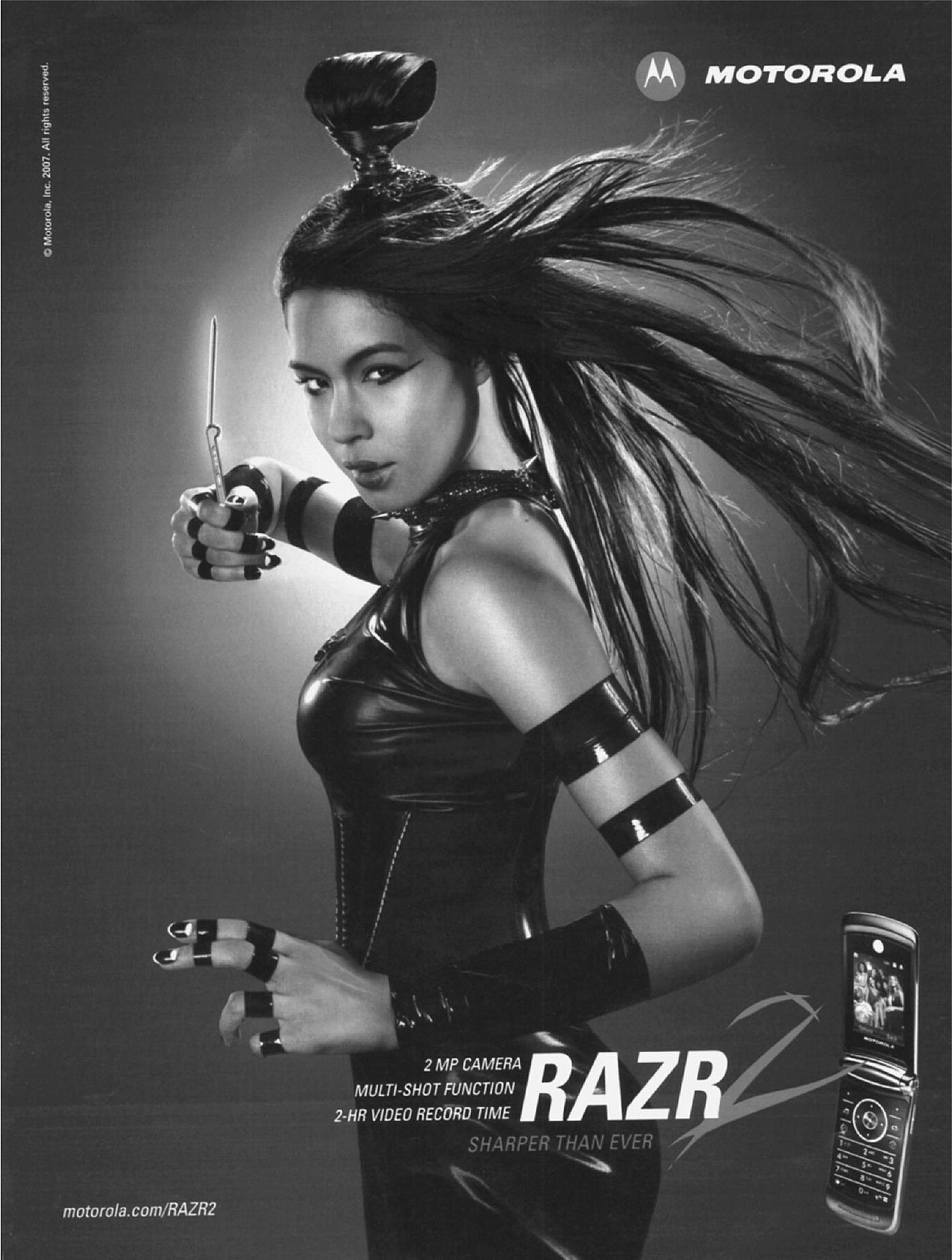

The notion of othering greatly illuminates the ways that many media texts function in America. One of the most prevalent forms of othering involves the ideology of difference, or the depiction of subordinate and racialized “others” as a source of pleasure for white consumers. Activist bell hooks characterizes this pleasure as a process of “eating the other,” where white individuals literally “consume” images and representations of racialized others in order to experience positive feelings. She suggests that within such an ideological structure, privileged white individuals act “on the assumption that the exploration into the world of difference, into the body of the Other, will provide a greater, more intense pleasure than any that exists in the ordinary world of one’s familiar racial group.”34 For a better understanding of how this consumption manifests in the media, consider Figure 6.4. From one vantage, the Motorola advertisement is certainly problematic in its reliance on a generic “Asian ninja” stereotype. Further inspection, however, leads to questions about the race of the actual model. It is unclear if she is Asian, Latino, white, or some other race (or combination of races). More problematic than stereotyping, then, is Motorola’s use of a generically consumable “Asian‐ness” in the image; something depthless that can literally be put on and taken off (or “tried out”) for pleasure and excitement.

Figure 6.4 Motorola Razr advertisement.

Source: Courtesy of The Advertising Archives.

Another common example of difference in contemporary media involves the hip‐hop music industry. Though popular hip‐hop musicians are overwhelmingly African American, and the genre is often characterized in the public consciousness as “African American” in style, many hip‐hop consumers are young, white, and middle class. Ideologies of difference help explain the draw of white suburbanites to this quintessentially African American form: to consume hip‐hop is to dabble in the other, to transgress racial norms in a self‐gratifying manner. Remember that the notion of gratification is crucial to understanding difference. While it may seem that actions based in difference reject racial norms in a progressively political light, in reality these moves reduce aspects of minority culture to mere products for privileged white individuals to consume toward their own ends.

Another way that othering can manifest in media is through the process of exoticism. Exoticism refers to the ideologically‐driven circulation and consumption of images of foreign lands that romanticize or mystify other cultures. Exoticizing a racial group often strips its members of contemporary political agency by constructing them as primitive, unintelligent, or animalistic. Virtually any issue of National Geographic magazine, for example, engages in this practice. One often encounters images of “tribal groups” while flipping through its pages, and these societies appear largely exotic and bestial in the context of the magazine’s stories on foreign lands and unusual animals. While National Geographic covers a variety of racial groups in this way, none of them are ever white. In examples like these, then, exoticism positions non‐white groups as socially and cognitively inferior to white, “civilized” society.

While difference represents actively seeking out aspects of non‐white cultures as a source of pleasure, exoticism represents a mental distancing and superiority of white culture over others. Together, they are the most prevalent forms of othering in American media. Othering, difference, and exoticism all ideologically reinforce white privilege by making whiteness the invisible and central concept in American race relations. These ideologies equate whiteness with normalcy, and white stands as the unspoken norm around which all other races revolve.

Conclusion

This chapter has looked at how television shows, films, music, news outlets, and other popular media forms privilege certain perspectives on social reality over others as a function of ideology. Operating under the ambiguous and flexible label of “Cultural studies,” scholars in this research vein seek to understand the ways in which the worldviews of socially privileged groups (men, whites, the wealthy, heterosexuals, adults, middle‐aged individuals, etc.) are over‐represented in the media to the detriment of socially marginalized groups (women, non‐whites, the poor, homosexuals, children, the elderly, etc.). They regularly critique media texts for their role in structuring hegemonic and ideological systems of power. Cultural studies is unabashedly political in relation to this goal, and the approach has produced some of the more radical and interesting research in contemporary media studies. The real strength of Cultural studies is its concentration on the ever‐changing dynamic between media texts and the social systems that create them. As US society continues to evolve in relation to media images and technology, the Cultural studies approach will continue to provide perspective on how ideology informs these changes.

SUGGESTED READING

- Aronowitz, S. How Class Works: Power and Social Movement. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2003.

- Benshoff, H.M. and Griffin, S. America on Film: Representing Race, Class, Gender, and Sexuality and the Movies, 2nd edn. Malden, MA: Wiley‐Blackwell, 2009.

- Brantlinger, P. Crusoe’s Footprints: Cultural Studies in Britain and America. New York: Routledge, 1990.

- Campbell, C.P. The Routledge Companion to Media and Race. New York: Routledge, 2016.

- Cloud, D.L. Hegemony or Concordance? The Rhetoric of “Tokenism” in Oprah Winfrey’s Rags‐to‐Riches Biography. Critical Studies in Media Communication 1996, 13, 115–37.

- Deery, J. and Press, A. (eds.) Media and Class. New York: Routledge, 2017.

- Dines, G., Humez, J.M., Yousman, B., and Yousman, L.B. (eds.) Gender, Race, and Class in Media: A Critical Reader, 5th edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2017.

- Dyer, R. White, 20th anniversary edn. New York: Routledge, 2017.

- Eagleton, T. Ideology: An Introduction, updated edn. London: Verso, 2007.

- Grossberg, L. We Gotta Get Out of this Place: Popular Conservatism and Postmodern Culture. New York: Routledge, 1992.

- Hall, S., Evans, J., and Nixon, S. (eds.) Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices, 2nd edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2013.

- Hoerl, K. Cinematic Jujitsu: Resisting White Hegemony Through the American Dream in Spike Lee’s Malcom X. Communication Studies 2008, 59, 355–370.

- hooks, b. Black Looks: Race and Representation. Boston, MA: South End Press, 1992.

- hooks, b. Where We Stand: Class Matters. New York: Routledge, 2000.

- Johnson, A.G. Privilege, Power and Difference, 3rd edn. New York: McGraw‐Hill, 2017.

- Kendell, D. Framing Class: Media Representations of Wealth and Poverty in America, 2nd edn. New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2011.

- Keys, J. Doc McStuffins and Dora the Explorer: Representations of Gender, Race, and Class in US Animation. Journal of Children and Media 2016, 10, 355–368.

- Larson, S.G. Media & Minorities: The Politics of Race in News and Entertainment. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2005.

- McIntosh, P. White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack. Peace and Freedom 1989, July/August, 10–12.

- Paulson, E.L. and O’Guinn, T.C. Marketing Social Class and Ideology in Post‐World‐War‐Two American Print Advertising. Journal of Macromarketing 2018, 38, 7–28.

- Shugart, H.A. Sumptuous Texts: Consuming “Otherness” in the Food Film Genre. Critical Studies in Media Communication 2008, 25, 68–90.

- Torgovnik, M. Gone Primitive: Savage Intellects, Modern Lives. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1991.

- Tukachinsky, R., Mastro, D., and Yarchi, M. The Effect of Prime Time Television Ethnic/Racial Stereotypes on Latino and Black Americans: A Longitudinal National Level Study. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media 2017, 61, 538–56.

- Tynes, B.M. and Noble, S.U. (eds.) The Intersectional Internet: Race, Sex, Class, and Culture Online. New York: Peter Lang, 2016.

NOTES