8

Feminist Analysis

In May 2016, the trailer for Ghostbusters: Answer the Call became the most disliked film trailer on YouTube, accruing approximately 800 000 downvotes from the site’s users.1 This disdain for the trailer mirrored much more explicit criticism of the film that had begun circulating online years before its July 2016 release. Some fans of the original Ghostbusters (1984) expressed disgust that anyone would attempt to update the classic they loved, and some cinemagoers more broadly lamented that Hollywood would release yet another reimaging in a summer already full of franchise remakes, spinoffs, and sequels. Writing for the Los Angeles Times soon after the film’s premiere, however, Rebecca Keegan noted what she believed was the overwhelming motivation behind the backlash: “The chief objection was that the busting of ghosts ought to be a strictly male pursuit.”2 While the 1984 film features four men as a team of paranormal investigators who rid New York of bothersome spirits, the 2016 version presents a largely identical plot with the exception that the team is made up of four women instead.

The rather pointed online hostility to an all‐female cast in Answer the Call indexes concerns at the heart of Feminist analysis. Feminist scholars concentrate on the ways in which the biological categories of male and female intersect with cultural expectations of gender to yield a social system that privileges men and masculinity over women and femininity. Feminist media scholars in particular concentrate on revealing the limiting nature of media texts that reinforce these dominant social understandings of sex and gender. As a result, feminism, like Cultural studies (see Chapter 6), is marked by a political commitment to deconstruct oppressive systems in order to transform society into a more equitable place for diverse people.

This chapter focuses on the place of feminism in understanding media texts. We begin with an introduction to feminism, paying particular attention to the ways in which it concentrates on issues of gender as a whole (and not, as is often portrayed in the mass media, on the needs of women alone). After briefly considering the roles and functions of stereotypes, we devote the bulk of the chapter to deconstructing common stereotypes of masculinity and femininity in the media and considering the impact of the “postfeminist” sensibility on the project of Feminist media studies.

Before we continue, though, we feel it is necessary to address a pressing issue. “Feminism” represents a fairly broad theoretical approach to media texts. There are many different kinds of feminism, each of which stresses particular aspects of social power and difference over others. In order to present an introduction to feminism without sacrificing its essential spirit, this chapter will concentrate on the main theoretical impulse(s) behind the tradition before considering representations of gender and sex in the media. If you find this theoretical introduction compelling, we encourage you to explore the diverse body of feminist scholarship at your leisure. See the Suggested Reading section at the end of the chapter for ideas.

Feminism: An Overview

Feminism, broadly, is a political project that explores the diverse ways that men and women are socially empowered or disempowered. It is often a highly charged word that requires some explanation to understand fully. Contrary to popular belief, contemporary feminism is not anti‐male. As cultural critic bell hooks defines it in Feminism is for Everybody, “feminism is a movement to end sexism, sexist exploitation, and oppression.”3Sexism is discrimination based upon a person’s perceived sex. Instead of targeting individual men or even men as a social group, feminism seeks to reveal and eradicate socially ingrained systems of sexism that harm all individuals in some way. It is a political project focused on deconstructing sexist oppression present in our everyday norms and experiences.

Two interlocking factors contribute to the creation of a sexist social system. The first is a misperception of sex and gender. Sex refers to the biological categories of male and female. Though many people think of sex in binary terms, or as a structure with only two available modes, feminist scholar Alison Stone argues that we should instead perceive male and female as “cluster concepts” that reveal a continuum of possible biological configurations. There are a number of biological markers that can help indicate a person’s sex, including chromosomes, internal/external anatomy, and hormone production. It is also true that certain biological markers tend to appear alongside or “cluster with” others in human development. An XX chromosome pair, for example, very often appears in individuals who also outwardly develop breasts, while an XY chromosome pair tends to appear in individuals who outwardly develop testicles. “When a human individual has enough of the properties in one of these clusters,” Stone writes, “that individual is male or female.”4 However, there are many instances where these markers do not cluster in expected ways, resulting in individuals who cannot be defined clearly by either of the two categories. Some people are born intersex, with anatomical variations or combinations that make it difficult to label them as either a girl or a boy. Some people change their sex in the course of their lifetime with surgical procedures and/or hormone supplements, resulting in exceptional combinations of biological traits (as Stone notes, even individuals who undergo a complete change of their outward sexual characteristics retain their chromosomal makeup). As a result, sex is best conceived of as a spectrum of biological arrangements historically or conventionally anchored by the categories of male and female.

Gender, conversely, refers to the normalized cultural categories of feminine and masculine. We utilize these categories when interpreting elements of social life like preferences, roles, behaviors, activities, and more. A uterus is a biological marker that we typically associate with the female sex, for instance, but mothering and nurturing are traditionally feminine behaviors. A low vocal register is a biological marker that we often associate with the male sex, but pronounced verbal aggression is a conventionally masculine activity. This foundation in social relations means that gender expectations are not only learned through interaction, but also vary widely depending on cultural context and time period. As Niall Richardson and Sadie Wearing point out, while it was a decidedly masculine behavior to wear voluminous wigs and flamboyant garments in certain 18th‐century Western societies, we would probably not consider such displays to be very masculine by today’s standards.5 Even within a given cultural context, the inherent variability of gender suggests that it, like sex, is best understood as a range of possible expressions for life historically and conventionally bounded by the categories of feminine and masculine. Very few people are entirely masculine or feminine in terms of their many daily preferences and behaviors.

Trouble arises when people uphold the categorical nodes within sex and gender as mutually exclusive distinctions, and especially when they believe that the learned aspects of masculinity and femininity are as inherent as the biological markers of maleness and femaleness (and align respectively). The first misperception does much to erase the diversity of the human experience, and we will take it up more fully in Chapter 9 on Queer analysis. The second belief, that gender distinctions are innate and/or natural expressions of assumed sexual distinctions, is called essentialism, and it will be a critical focus for the remainder of this chapter because it is a prevalent factor in the ways that many people think about sex and gender today. If sexism is discrimination based on a person’s perceived sex, then widespread essentialism supports this practice by opening up a vast range of otherwise irrelevant tastes and activities for judgment. If we believe that all women are also inherently predisposed to excessive emotional displays, for instance, then emotion becomes a meaningful topic on which to decide the worth of women more generally.

The second factor that contributes to the formation of a sexist social system is patriarchy. Patriarchy is a system of power relations in which the interests of women and the value of femininity are subordinate to the interests of men and the value of masculinity. It is the logic of sexist discrimination. Once we have (however erroneously) sorted the world into male and female, masculine and feminine, the logic of patriarchy consistently denigrates women and femininity to the benefit of men and masculinity. We can see patriarchal logic operating especially in relation to work in America. If we believe that women are innately more nurturing than men, then it consequently makes sense for women to stay home with newborn children while men continue to work, earn money, and build their skills sets. If we believe that women are predestined to struggle with math and science, then it makes sense that the majority of workers in high‐paying and prestigious engineering and medical occupations are men. In each case, essentialist beliefs about gender lead to normalized practices where men tend to gain economically, professionally, or socially. The tangible benefits that men reap from such a system make them far less likely to challenge patriarchy than women.

Does the fact that men benefit from patriarchy and are less likely to resist it mean that all men are automatically sexist? To answer this question, it is helpful to consider the difference between individuals and social systems. So, we turn to an analogy adapted from Allan G. Johnson’s Privilege, Power and Difference.6 Most people do not think of themselves as excessively greedy in their everyday lives, and the majority of people conceive of greed as a negative character trait. Most people, however, have probably exhibited extremely greedy behaviors while playing the game Monopoly at some point in their lives. Almost everyone has spent at least one rainy afternoon buying up properties on the Monopoly board and showing little financial mercy when siblings, parents, or friends land on them. In short, we may not think of ourselves as fundamentally greedy individuals, but we absolutely exhibit greed while playing Monopoly. The same can be said about how we act in a sexist social system. We may not consider ourselves sexist in the sense that we do not consciously discriminate against people in our everyday life, but when we play the “game” of sexism – when we go out into the world and take part in social systems that are inherently sexist – we, in a sense, are sexist as well. Social systems cannot happen without people, just as Monopoly cannot play itself, but (as with games) we tend to enact social systems according to the rules and expectations determined long before we as individuals joined them.

So, to answer the question posed before: yes, all men are sexist. But, in some sense, so are all women, because everyone tends to enact sexist social conventions inattentively. That having been said, because of the disproportionate negative effects of patriarchy on women, it is crucial to acknowledge that sexist behavior enacted by women often looks quite different from sexist behavior enacted by men. Whereas men might objectify women for their sexual satisfaction (or at least feel pressured to do so), women might hold themselves to impossibly high or unhealthy beauty standards (or feel pressured to do so). In a 2017 article for USA Today titled, “You’re Sexist. And So Am I,” Aria E. Dastagir lists a number of other ways in which women continue to “internalize” sexism in the contemporary era, including downplaying their careers for the purposes of building a family and even policing other women who openly criticize sexist practices.7 In suggesting that all people are sexist, we do not also mean to imply some sort of equivalency. After all, sexism is enacted by men and women in very different ways and with very different consequences.

Realizing that all individuals are subject to sexist social conventions in varying ways opens up important understandings about feminism. Feminism certainly attempts to recognize and disable patriarchal social systems that disempower individual women, but more recent feminist scholarship has also begun looking at the ways in which patriarchy harms everyone regardless of sex. The gendered expectations that patriarchy places on women necessarily exert pressure on men as well, often demanding that men show little emotion, avoid certain occupations, or act as the breadwinner for their family. This fact underscores the wide scope of the contemporary feminist project. Everyone is harmed by sexist social systems, but patriarchal power relations significantly increase the harm they do to women. And because both men and women help enact these systems, both women and men can be feminists in their attempts to resist them.

In addition to considering the ways in which gender expectations are harmful, much feminist work today also assumes a perspective of intersectionality, attending carefully to the ways in which gender intersects with other forms of difference like race, class, sexuality, and ability in the lived experiences of individuals. An intersectional analysis might study the impact of socio‐economic status on perceptions of domestic violence, or it could reflect on the role of lesbianism in historical struggles for women’s suffrage. This perspective enriches feminist understanding by reminding scholars that issues of gender privilege and subordination do not operate in a vacuum, and that two individuals who identify as the same sex or with the same gender norms may nevertheless differ in other significant ways. Especially for contemporary feminist media studies, an intersectional approach to gender “centers the interpretive practices of quickly growing communities, such as Latinas and Asians in the United States, and African and Muslim women in Europe, among others.”8 Intersectionality thus provides a more nuanced understanding of how sexism operates in an increasingly multicultural and complex mediated environment.

Feminist media scholars generally understand media texts as products of sexist social systems, and they look especially at the many ways in which patriarchal logic informs the creation of these texts. Scholars in this tradition analyze television programs, films, magazines, radio programs, and websites to understand how these texts reflect, support, and create systems of unequal gendered power. Though contemporary feminist scholarship is complex in its analysis of the media, the issue of gendered representation and stereotypes is a historically primary focus that still has relevance for today. The remainder of our discussion on feminism will concentrate on media representations of gender and how particular media texts express stereotypes. First, however, it is important to understand fully the social role of stereotyping.

Stereotyping in American Media

A stereotype is a misleading and simplified representation of a particular social group. You are probably familiar with many stereotypes already: the elderly drive badly, fraternity members attend college to party, and people from the Southern United States are not very smart. Stereotypes are damaging because they gloss over the complex characteristics that actually define a social group and reduce its members to a few (usually unfavorable) traits. When these stereotypical representations become commonly accepted in the media, the result is often the social oppression and disempowerment of individuals within the stereotyped group. Many people have had experiences with stereotypes. And yet, if the vast majority of people know that stereotypes are false and socially damaging, why do they persist in life and the media? There are a few different answers to this question.

A conventional but nonetheless accurate critical explanation for the presence of stereotypes in the media is something akin to the following: socially powerful groups like men have greater access to media outlets as a function of privilege, and this access grants them the ability to represent their particular impressions of other social groups to the widest audiences. These perspectives are often stereotypically reductionist, but they become the most widely known and accepted representations of these social groups. While the repetition of stereotypes is certainly a powerful force in securing their place in the American context, however, it is important to consider how other qualities of stereotypes contribute to their enduring presence in the media as well.

First, everyone stereotypes. Stereotyping helps individuals make sense of an increasingly complex contemporary society. As social creatures, we absorb and reflect upon the experiences that we have with others, and we use past experiences to make sense of present and future interactions. Stereotypes, or the mental categories of people that we carry with us, allow us to quickly process incoming information about strangers by greatly reducing the amount of information we have to absorb. If we actually took the time to notice the subtle nuances of every individual we encountered on a daily basis, then we would spend much of our lives discussing social issues with every street petitioner and the pros and cons of credit card adjustment with every telemarketer. Stereotypes, however inaccurate, form mental shortcuts that allow us to quickly make snap judgments about individuals and move on.

Moreover, for such simplistic reductions of character, widespread social stereotypes are actually rather intricate in their construction. You may have heard the saying that there is a “kernel of truth” to every stereotype. This is correct to the extent that stereotypes often blend realistic elements of life, material conditions, and social roles into inaccurate assumptions and false traits. The continuing power and “strength of stereotypes lies in this combination of validity and distortion.”9 Stereotypes persist in the media because they have enough truth to sound plausible without much critical thought. To complicate the matter, sometimes members of socially oppressed groups will believe media stereotypes about themselves to be true and emulate them.10 In this case, stereotypes mimic reality by creating it. Stereotypes often persist, then, because it is difficult to distinguish their truth from their falsity.

The fact that everyone stereotypes to some degree and that aspects of stereotypes often ring true helps explain a rather unique function of stereotypes in the media: they often lend texts a certain sense of credibility with audiences.11 When we see a sitcom with a foreign exchange student speaking in broken English, or when we watch a movie that features a group of black gang members, these representations unfortunately “ring true” with the stereotypical knowledge we already have as members of society. Put differently, media images that feature stereotypes gain an informal credibility because they match some of the common stereotypes people use every day to reduce information processing. Media producers who present textual representations that challenge social stereotypes risk losing this informal credibility. While the media create and reinforce stereotypes just as much as they use them to attract audiences, the issues of stereotyping and credibility remain a powerful influence.

In discussing these issues, we do not wish to give the impression that the media use of stereotypes is permissible because stereotyping is a human tendency, a quasi‐reflection of reality, or an effective way to appeal to audiences. We also do not excuse individuals who ignorantly hold racial, gendered, sexual, or other stereotypes. Stereotypes are harmful by nature, and we should work to eradicate them as much as possible. In this section, we simply hope to situate our discussion of gendered stereotypes within a larger framework of the complex ways that stereotyping operates in the media and society. This will deepen our understanding of the power and place of the various mediated stereotypes we are going to look at. Keep these various aspects in mind as you read the next section. Consider how issues like human tendency, reflections of reality, and audience adaptation methods inform the creation of stereotypes.

Gendered Stereotypes in American Media

Exceptions exist for every rule. Recognizing exceptions is the mark of quality scholarship and true understanding. With that in mind, the stereotypical images of gender we discuss in this section signify some of the general, overarching, historical trends within media representation most apparent in Feminist criticism. They are by no means absolute truths. The contemporary American media landscape is far too diverse to fit only within the narrow range of these stereotypes. As archaic as they may sound, however, they continue to thrive in media today, and concentrating on them should provide a useful initial glimpse into the process of Feminist analysis.

American society features a historically entrenched understanding of gender that conflates men with masculinity and places them in opposition to women and femininity, and we see this schema manifest in gendered stereotypes in the media that function as complementary inverses of one another. In general, stereotypes of men and masculinity are defined by power, significance, agency, and social influence. Stereotypes of women and femininity are defined by powerlessness, insignificance, passivity, and limited control. Though these trends construct narrow gender norms for individual members of both sexes, they also reinforce patriarchal systems of power and tend to support the domination of men over women. The four interrelated, stereotypical binaries we focus on in this section are active/passive, public/private, logical/emotional, and sexual subject/sexual object.

Active/passive

Mainstream media representations of men are often marked by strength and activity. Advertisements tend to depict men engaging in sports, working with tools, or driving powerful vehicles, and the models in these advertisements are often full of vitality or in good physical shape. Images of women, on the other hand, tend to emphasize passiveness and weakness. Female models often simply sit or stand beautifully to advertise their product, and many of them possess dangerously underweight figures.12 This general contrast between men and women in advertising is striking, but its repetition across many different kinds of ads makes it seem normal. Notions of power and physical prowess begin to define masculinity and “being a man” in American society, while femininity and “being a woman” are tied to passive acceptance and helplessness.

Consider the difference in gendered representation between the two “Got Milk?” ads in Figures 8.1 and 8.2. The one with Jackie Chan exudes masculinity. The daring aerial escape from a burning car constructs Chan as physically strong and in control of his situation, so much so that he can kick a milk bottle with precision despite a rather threatening environment. Though there is a great deal of activity in the scene itself (an ascending helicopter and raging flames, for example), the focus here is on Chan’s agency. In fact, Chan is so sure of his abilities in this situation that we see him literally laughing in the face of danger and taking time to educate readers on the importance of drinking milk. The cityscape that fills the background reminds us that action always requires a context; a subject’s actions make no sense unless we understand what prompts them. Additionally, this advertisement conjures many images of Chan’s film career, where the actor often portrays a powerful martial artist. Even if one has never seen a Jackie Chan film before encountering this advertisement, the image reflects the “action hero” trope popular in mainstream Hollywood films.13 Overall, the Chan advertisement taps into many different American cultural codes in order to present an image of masculinity marked by power and strength. In some ways, it is easy to forget that this is an advertisement for milk.

The advertisement with model Kate Moss provides a marked contrast to the one with Chan. Glancing back over her shoulder, her arm shielding her breasts from the curious eye of the camera/viewer, Moss’ pose is innocent and inviting. She is naked and therefore completely vulnerable, and her body is certainly on display for the viewer in a way that Chan’s is not. The text, which references Moss’ famous facial bone structure, draws additional attention to her physical beauty rather than her abilities or talents. A recognizable background would at least allow readers to imagine Moss reacting to her environment, but the lack of any context here signals that Moss is merely to be visually consumed like a piece of art. The image of Moss also invokes the cultural notion of the pretty, demure model, an individual whose entire career involves constantly being directed by others. Through these various visual cues and references, the advertisement presents an image of femininity defined by passivity and vulnerability. Whereas the Chan ad implies that drinking milk will make readers active and strong, the Moss ad suggests that drinking milk will leave one passive and exposed.

Figure 8.1 Milk advertisement with Jackie Chan.

Source: Courtesy of The Advertising Archives.

Figure 8.2 Milk advertisement with Kate Moss.

Source: Courtesy of The Advertising Archives.

Public/private

The binary of active man/passive woman helps shed light on other, related gendered stereotypes. Popular American television shows and films often draw sharp distinctions between men and women in relation to public and private spheres. Because men are represented as active and strong, they also tend to fulfill the role of “family provider” in these texts. Audiences often encounter scenes in which men are working, acting as the breadwinners for their families. Women, in contrast, are coded as passive and weak, and media texts therefore tend to represent them as the “family nurturer.” The common sitcom image of the housewife is the most obvious expression of this. Here, the woman’s responsibility is to nurture the family by cleaning the house, taking care of the children, and fixing meals. Older television couples, such as Fred and Wilma Flintstone or Ward and June Cleaver (of Leave it to Beaver), perfectly embody these binary stereotypes.

Contemporary audiences may consider the provider/nurturer stereotype to be largely a thing of the past, and it is true that some media texts portray heterosexual couples with a much more fluid understanding of family roles. Despite examples of progressive programs, however, this stereotype continues to endure in popular American television programming. The Simpsons is an excellent example. Homer Simpson may be inept in his job at the Springfield Nuclear Power Plant, but he is consistently the sole source of income for the cartoon family. Throughout the run of the show, audiences have laughed at Homer’s various misguided but heartfelt attempts to provide for the Simpsons. In the first full‐length episode of the series, for example, Homer fails to get a Christmas raise and takes a job as a mall Santa to earn the money needed to buy Christmas presents. Though he loses the Santa job and gambles away his meager paycheck at the Springfield dog track as a last resort, he ends up securing a “Christmas” puppy for the family in the process. At various points throughout the series, Homer also works as a bartender, chiropractor, bodyguard, salesman, sports mascot, and talk show host in order to be an effective breadwinner.

In contrast, Homer’s wife Marge spends most of her days as the doting housewife. Multiple episodes reinforce Marge’s centrality to the Simpson home. In one, Marge cracks under the pressure of her domestic responsibilities and leaves the family for a relaxing vacation, and the household promptly falls apart. Homer is at a loss without Marge’s nurturing skills and ends up “misplacing” their youngest daughter Maggie. When Marge eventually returns, the family begs her to never leave them again. We see this theme again in a later episode where Marge is injured at a ski resort and leaves her domestic responsibilities to her daughter Lisa. The home devolves into a complete mess in only a few days. Apparently, the Simpson home cannot survive without Marge as its domestic nucleus. Additionally, even though Marge takes on various jobs throughout the series (including as an actress, an artist, and a pretzel‐maker), these never last longer than an episode. When Homer fails at his second jobs, he can always return to the power plant. Marge simply returns home.

Logical/emotional

The association of the public, working sphere with men and the private, domestic sphere with women feeds into a third related gender binary: logic/emotion. Traditionally, media texts construct logic as a masculine trait and emotion as a feminine one. The masculine public sphere is related to politics and decision‐making, so masculinity is marked by the kinds of rational thinking associated with these processes. The private sphere is concerned with family and nurturance, so femininity is defined by irrational or emotional impulses. A classic form of this stereotypical dualism is the association of men with mental processes and women with bodily ones, and the effect on our perceptions of gender is very much the same.

A good example of the logical/emotional binary can be found on the popular syndicated television series Star Trek: The Next Generation. Lieutenant commander Data (Brent Spiner) and ship’s counselor Deanna Troi (Marina Sirtis) are clear manifestations of these gender stereotypes. Data is an android, or a “mechanical man,” made completely of circuitry and synthetic materials. His technology is sophisticated enough that the crew of the starship Enterprise considers him to be an individual with a personality, but Data lacks the ability to feel any emotion. He approaches problems throughout the series with a cool logic and clear predilection for reasoned decision‐making. Though Data experiments with humor and special devices that give him the ability to emote throughout the series, these choices often diminish his problem‐solving skills and at times even put his crew in danger. Data never actually achieves his desire to be a “fully‐feeling” human.

Troi is largely the opposite. As the ship’s psychological counselor, she is responsible for listening to crewmembers’ problems and helping them through difficult emotional issues. Troi is part Betazoid, an alien race in the Trek universe who can empathically sense what others are feeling. This factor heightens her counseling abilities and often positions her as the ship’s moral conscience and emotional expert. A number of episodes hinge on Troi being able to discern individuals’ motivations and intentions through fluctuations in their emotional states. At the same time, Troi’s empathic abilities also backfire at certain points when she cannot stop the flood of others’ emotions from overtaking her; she actually becomes an emotional “dumping ground” for an alien political mediator in one episode. A handful of episodes in the series also concentrate on her emotionally complicated relationship with her mother, Lwaxana (Majel Barrett).

Data and Troi are nearly perfect examples of the logical/emotional gender binary. Despite their best efforts to resist, each character is dominated by a stereotypically gendered way of understanding the world around them. While (masculine) Data cannot experience emotion, (feminine) Troi sometimes cannot stop experiencing emotion. This duality is especially interesting in light of the original character sketches producers used while casting actors for the series. While Data should be “in perfect physical condition and … appear very intelligent,” Troi need only be “tall (5′8–6′) and slender, about 30 years old and quite beautiful.”14 Such a distinction begins to illustrate the subtle connections between stereotypes. Beauty, emotion, and femininity are stereotypically bound together in a single character in this program.

Sexual subject/sexual object

The final gendered binary is related very strongly to the first three. Masculine stereotypes of strength, ability, and intelligence often translate into media images of sexual subjectivity. In other words, media texts tend to identify men as sexually powerful and pursuant. To be masculine is to be “in charge” of the sexual encounter, to direct its progress and “make it happen.” Feminine stereotypes of weakness and emotion in turn give rise to the sexual objectification of women. Media representations of women construct them as sexual conquests to be pursued and lusted after. To be feminine is to be available, responsive, and open to male sexual advances. The famous French feminist Simone de Beauvoir captures the sexual subject/object binary poetically in her treatise on the oppression of women, The Second Sex:

For him she is sex – absolute sex, no less. She is defined and differentiated with reference to man and not he with reference to her; she is the incidental, the inessential as opposed to the essential. He is the Subject, he is the Absolute – she is the Other.15

Journalist Naomi Wolf echoes de Beauvoir in her proposal of the beauty myth, or the cultural beauty standards that continue to control women in an apparently progressive society. For Wolf, “the beauty myth tells a story: The quality called ‘beauty’ objectively and universally exists. Women must want to embody it and men must want to possess women who embody it.”16

Examples of the sexual subject/object binary cut across media texts, ranging from relatively innocent representations to more obviously hedonistic ones. The Disney film Sleeping Beauty (1959) is a good example of a chaste children’s media text that nevertheless hinges on this binary. Princess Aurora falls into a deep slumber after pricking her finger on a spinning wheel spindle cursed by the evil fairy Maleficent. The only act that can break the curse and wake the princess is a kiss from her true love, Prince Philip, who spends the second half of the film attempting to break free of Maleficent’s clutches in order to reach Aurora. The entire narrative resolution rests on Philip’s pursuit of Aurora, who passively awaits her prince while sleeping atop a high castle tower (very much on erotic display in a beautiful bed). In this text, Philip is clearly the active, pursuant sexual subject, and Aurora is the passive, waiting sexual object he seeks. The film itself is not highly sexual, but it tacitly promotes this stereotypical binary.

Of course, this binary is even more present when the sexual content of the text is more explicit. The number of mainstream “sex comedies” that portray horny young men pursuing women as conquests is almost too large to count: the American Pie series (1999–2012), the Porky’s series (1982–85), Animal House (1978), Old School (2003), Superbad (2007), That Awkward Moment (2014), and so on. The advertisement for Wild Turkey in Figure 8.3 provides another example that frankly links masculinity to sexual power. The strip club here is empty except for the erotic dancer and her male customer, who appears to have enough influence or money to command a private dance. Importantly, he stares at her body instead of her face, which is not incidentally cropped out of the image. We are to understand her here as a sexual object and not a full person. Any notion that this man is transfixed or otherwise powerless in the presence of the dancer is obliterated by the caption, which reminds the viewer that he is fully in control of the sexual situation. Indeed, the thinly veiled substitute of the Wild Turkey bottle for his own anatomy suggests that he is primed to move the sexual encounter forward.

Figure 8.3 Wild Turkey advertisement.

Source: Courtesy of The Advertising Archives.

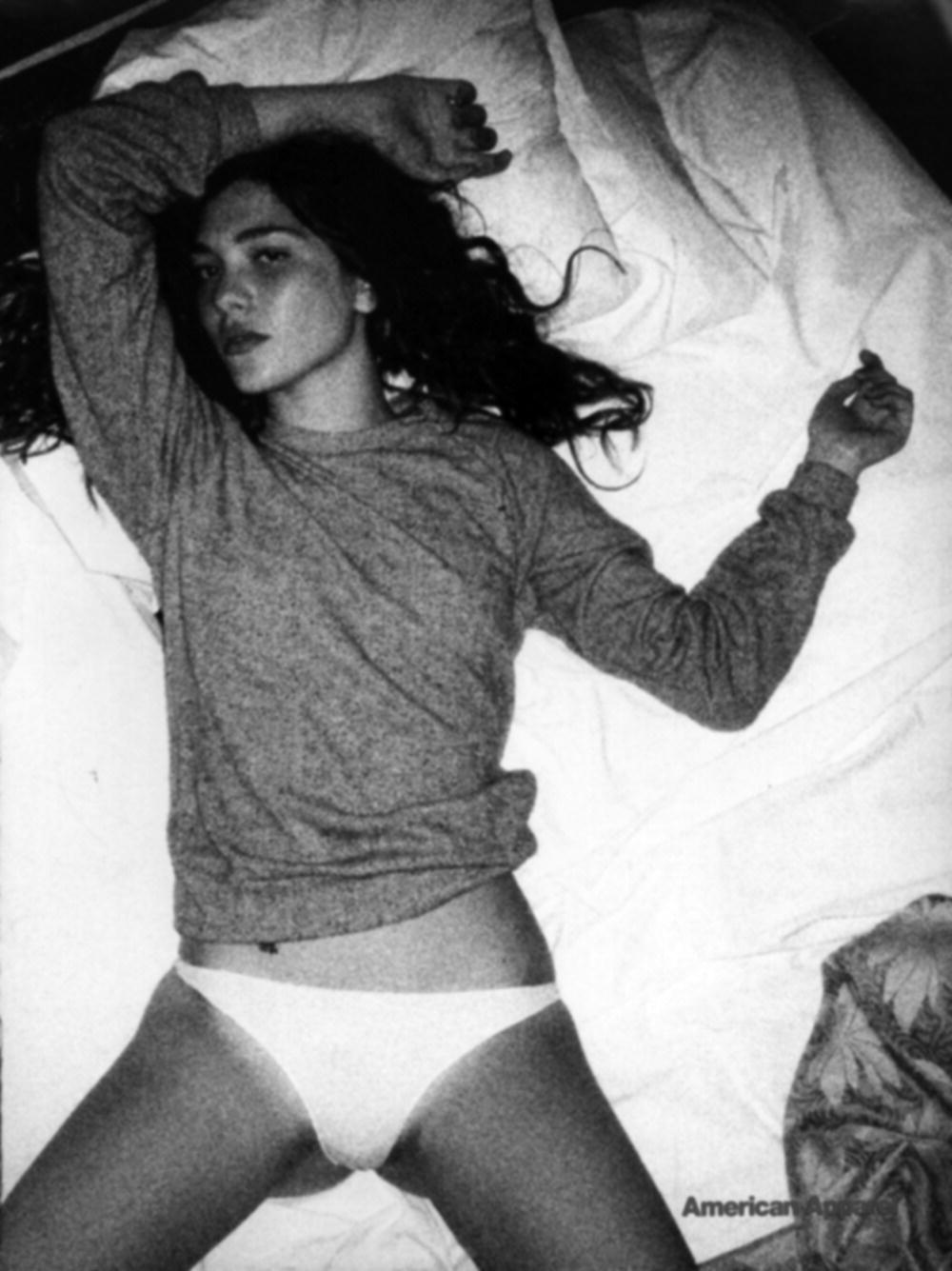

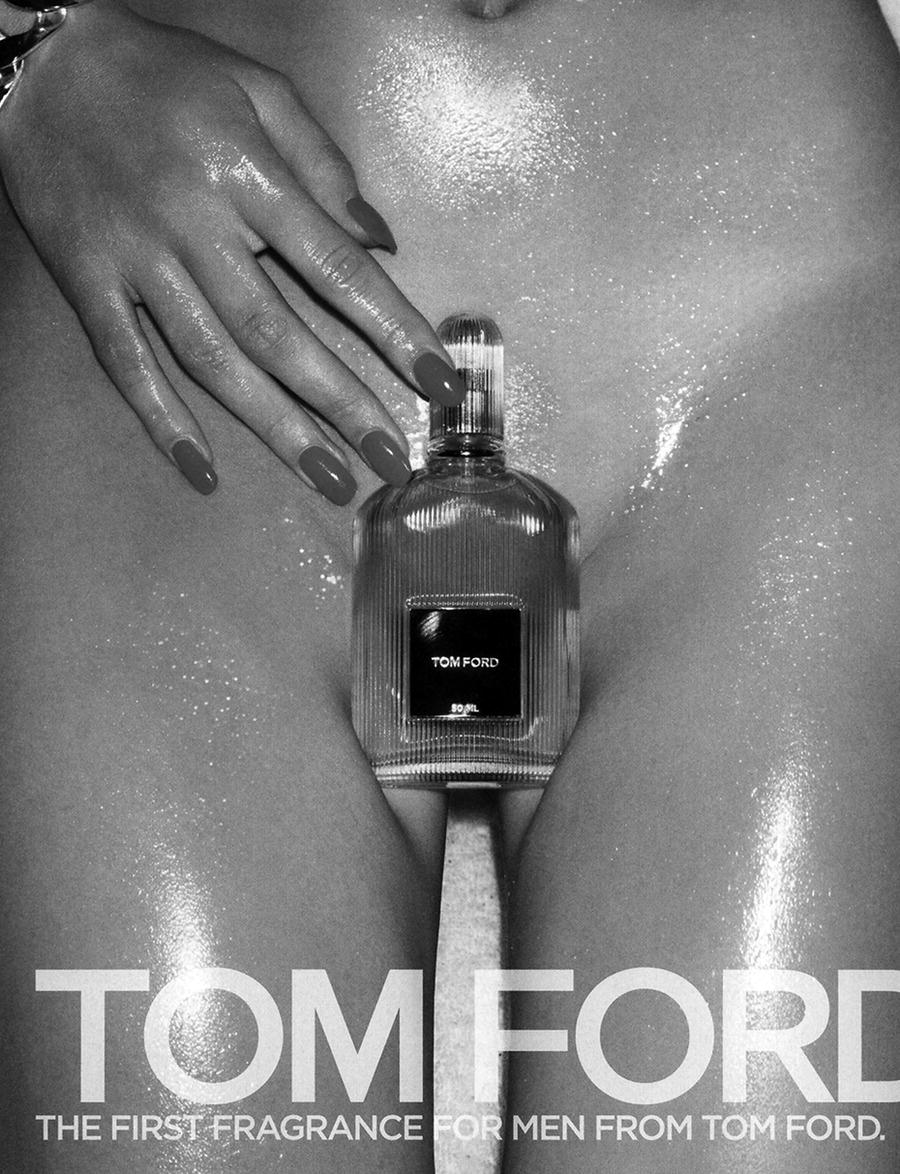

In some ways, the subject/object distinction differs from the others we have discussed because it can function as the basis for a relationship between media text and media consumer as well. Rather than confine the notion of sexual pursuit to the “world” of the text, many media texts feature women as sexual objects, with the assumedly male consumer as a complementary sexual subject (see Chapter 7 on Psychoanalytic analysis for an in‐depth discussion of this relationship). Advertising is especially notorious for establishing and trading upon this type of relationship, with representations of female objects that range from merely suggestive (Figure 8.4) to outright pornographic (Figure 8.5). The highly popular video game Grand Theft Auto V offers an additional example. The three playable characters in the game are all male, and many of the female characters with whom players can interact are prostitutes or strippers. The game grants the player the ability to hire these female characters for fairly graphic sexual escapades, as well as the option to kill them afterward in order to recoup their funds. Even more than the implied relations in advertising, then, GTA:V quite literally affords media consumers the ability to act as men who pursue women only as sex objects.

Figure 8.4 American Apparel advert.

Source: Courtesy of The Advertising Archives.

Overall, gendered stereotypes of masculinity and femininity influence the possible roles that individuals can fulfill in society. Though these images by no means dictate or control how people actually act, they are powerfully persuasive in constructing the social rules we tend to live by unconsciously. When we belittle sexual harassment policies or dissuade young girls from playing football, or when we raise our eyebrows at the mention of a stay‐at‐home dad or encourage young boys to look tough and hold back tears, we are enacting the social rules regarding gender disseminated by the media. It is in these moments that supposedly outdated gender stereotypes continue to manifest as very real influences on our lived experience. Though patriarchal systems of power ensure that media stereotypes tend to disempower women more than men, in actuality all individuals are harmed by these limiting images.

Figure 8.5 Tom Ford advertisement.

Source: Courtesy of The Advertising Archives.

Postfeminism and Media Representation

Though difficult to define clearly, postfeminism broadly refers to a conceptual shift within the popular understanding of feminism, an evolution in feminist emphasis from the systemic oppression of all women to the empowerment of individual women. It is important to look at the history of feminism to understand the role of postfeminism. The term first‐wave feminism refers to the work of 19th‐ and early 20th‐century activists like Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony who primarily fought for women’s right to vote. Second‐wave feminism refers to the work of activists in the 1970s like Gloria Steinem and Betty Friedan who fought for women’s workplace and reproductive rights. The progress made by second‐wave feminists in relation to women’s occupational and sexual roles throughout the 1970s prompted some people to wonder if the feminist goal of sexual equality and freedom had in fact been achieved. Those who continued to interrogate the systemic role of gender in relation to intersectional concerns like race and class became members of third‐wave feminism. Those who instead claimed that the systemic focus of feminism had, indeed, “done its job” were labeled postfeminists. The postfeminist logic was fairly straightforward. Since prior incarnations of feminism had finally given women an “equal” place in society, any remaining feminist project should turn attention to women’s “individualism, sophistication and choice.”17 Additionally, postfeminists critiqued second‐wave feminists for what they saw as an overly negative view of the traditional family structure. Women, according to postfeminists, could have both a career and a family, be both empowered and nurturing. Quite simply, women could be whatever they wanted to be.

Beyond this historical positioning, however, it is difficult to pin down a clear definition of what it means to be a postfeminist today. Rosalind Gill, responding to this relative lack of understanding, frames postfeminism as a “sensibility” made up of a number of interrelated aspects: (1) a melding of femininity, female sexuality, and the body as a response to an increasingly sexualized culture; (2) the dominance of philosophies of individual choice and responsibility, with a concurrent focus on self‐discipline and surveillance; (3) the support of theories of irrevocable sexual difference between men and women; and (4) a reliance on irony and “knowingness” as a means of navigating cultural messages.18 Gill points to a number of media texts as evidence of these qualities, including women’s magazines and popular “make‐over” television shows, in order to show how qualities like sex differentiation and self‐surveillance manifest in diverse media outlets. Her identification of these qualities does not indicate her embrace of them. In fact, she remains rather suspicious of the supposed empowerment that postfeminist doctrines of individualism, sexuality, and choice offer to women. In reflecting on postfeminism’s philosophy of choice and women’s claim to acting sexy “for themselves,” she points out that

it presents women as entirely free agents and cannot explain why – if women are just pleasing themselves and following their own autonomously generated desires – the resulting valued “look” is so similar – hairless body, slim waist, firm buttocks, etc. … It simply avoids all the interesting and important questions about the relationship between representations and subjectivity, the difficult but crucial questions about how socially‐constructed, mass‐mediated ideals of beauty are internalized and made our own.19

Gill’s suspicion is indicative of many Feminist media scholars’ perspectives on the postfeminist sensibility, and it gets at the heart of a current debate over postfeminism, especially in relation to media studies. On one hand, the rise of postfeminist discourses helps explain the presence of some media representations of gender that appear to challenge classic stereotypes. Scholars disagree over when postfeminist ideals of women’s empowerment and agency really took hold in the media,20 but since the 1980s, media representations of women have increasingly depicted them as able, intelligent individuals. Media texts like Bridget Jones’s Diary (2001), Sex and the City, Scandal, and Orange is the New Black feature strong, independent heroines who mostly have the ability to satisfy their own economic, sexual, and emotional needs. These images are a far cry from those of the doting housewife, the emotional wreck, or the passive sexual object that dominated earlier media representations of women. On the other hand, as we have pointed out in this chapter, many traditional gender stereotypes continue to appear within the media. Echoing Gill’s sentiments, Angela McRobbie suggests that postfeminist claims regarding the inapplicability of earlier feminist politics are ill‐founded and ignore the fact that real, systemic, gendered inequity continues to inform the lives of many women.21 Patriarchal power structures may have loosened their hold on women, but they are far from gone.

An excellent example of media textual analysis that looks at the interplay between the postfeminist sensibility and continuing issues of women’s oppression is Sarah Becker, Danielle Thomas, and Michael R. Cope’s study of films featuring the popular line of Bratz dolls for children.22 In one sense, the films regularly emphasize the importance of young girls finding and expressing their individuality. Many of their plotlines concern a young woman who learns to overcome her self‐doubt in order to forge a more confident identity, especially though the affirmations of other female characters and with a communal, multicultural orientation toward problem solving. From this vantage, the authors contend, the Bratz films may seem empowering to women and very much in line with Feminist concerns and methods. However, in another sense, the films often reprimand female characters who stray too far from conventional norms of femininity, especially in relation to questions of fashion and beauty. The logic of free choice in the films is also unmistakably consumerist, as the vast majority of plots show the Bratz buying outfits at the local mall or engaging in fashion makeovers with numerous beauty products. This conflict between choice and consumption leads the authors to a mixed conclusion about the feminist implications of the films. Rather than

consistently embracing post‐feminist tropes, the films oscillate between embracing/valuing feminist rhetoric and repacking it in decidedly post‐feminist ways … The Bratz girls unite with each other and a diverse set of “others” to achieve change. However, rather than work to make a better society, they unite to make a better self. Using shopping and a very specific type of femininity, they create a commercialized and uniform self that is lauded as individual and authentic.23

Postfeminist themes of choice and identity in the films thus become another means of policing women and peddling a shallow understanding of empowerment. Clearly, merely asserting that women can be whatever they want does not make it so.

The tension between feminism and postfeminism exists as well in texts aimed at a much wider audience than the Bratz films. In the popular young‐adult book and film series The Hunger Games, for example, the main character Katniss Everdeen appears to challenge traditional representations of femininity. Raised in the harsh world of Panem, a futuristic society erected upon the ruins of a fallen United States, 16‐year‐old Katniss is independent, intelligent, and brave. Though initially terrified of representing her home district in the annual Hunger Games (a lethal, state‐sponsored Olympics), she also realizes that she possesses many skills that other women in her district lack. These skills are instrumental to her survival and eventual victory in the Games. Her open defiance of state tradition on national television at the end of the first book/film makes her a popular folk hero and a wanted citizen by the government. As the state attempts to destroy its new victor and stamp out a series of social rebellions inspired by her actions, Katniss joins forces with an underground revolutionary movement and assumes the mantle of the Mockingjay, or the symbol of freedom for the oppressed peoples of Panem.

Despite these images of empowerment and choice, Katniss is not completely free of more traditional stereotypes of women. Though at first indifferent to her fellow Games participant Peeta Mellark, for instance, Katniss quickly finds herself embroiled in a love triangle with him and fellow survivalist Gale Hawthorne. As the series progresses, Katniss appears to spend less time worrying about the unprecedented social revolution she sparked and more time agonizing over her conflicted romantic feelings. Additionally, for all of her trademark self‐reliance, Katniss’ actions are largely guided throughout the series by two male authorities: Haymitch Abernathy, a past Games winner from her home district who functions as her mentor, and Cinna, a personal stylist who functions as her friend and confidant. Many of Katniss’ best strategies in and out of the Games come from these two men. It is Cinna, for example, who engineers Katniss’ signature “girl on fire” and Mockingjay looks that become the crucial symbols of rebellion in the series. These narrative points, coupled with the fact that Katniss must essentially mother her young sister Primrose (as well as Rue, a participant in the Games), suggest that even a revolutionary cannot completely escape mainstream codes that represent women as emotional, deferential, or domestic.

It is probably safe to say that the Hunger Games series is representative of a more general impulse within contemporary media in relation to issues of gender. The series is certainly progressive when compared to older media texts with defined gender stereotypes, but it is also problematic in its maintenance of certain stereotypical themes (and perhaps does even more damage by concealing them within overarching messages of female empowerment). In analyzing The Hunger Games, we can see that neither the extreme postfeminist nor traditional second‐wave assessments of media representation of gender are wholly correct. In truth, many media texts today are complex presentations that require careful deconstruction across many layers of meaning, and Feminist media scholarship is constantly examining and assessing their complexity.

Consequences of Sexist Media Representation

Media texts influence people. The television shows we watch, the songs we listen to, and the websites we visit give us an impression about the world and how we should live in it. We have probably all been moved to tears by a particular film or convinced to purchase a product by a clever advertisement. When media texts present us with skewed images of gender and sex, it is understandable that some people will take those stereotypes as “the truth” and act upon them. In this section, we wish to outline some of the major, real‐world consequences of sexist stereotypes in the media. Far from existing as mere entertainment, these images are crucial in constructing the social world of American culture.

One of the most prevalent material effects of mediated gender stereotypes is a modern proliferation of eating disorders. Stereotypes that construct women as passive or sexually attractive also tend to emphasize the absolute necessity of a slender figure. American daytime and primetime television programs have historically portrayed female characters as skinnier than their male counterparts, while the remaining “overweight” characters are less likely to be portrayed in a romantic light.24 Even newer forms of media like Instagram tend to emphasize the notion that a fit and healthy female body is also a thin one.25 Dieting advertisements that once focused on overall weight now regularly talk about zapping problem areas that are “soft, loose or ‘wiggly’” in an effort to rid the body of any sign of fat.26 Somewhat paradoxically, advertisements for food continually encourage Americans to indulge in excess even as we learn that “fat is bad.” Advertising analyst Jean Kilbourne views eating disorders as one of the primary ways that “women cope with the difficulties in their lives and with the cultural contradictions involving food and eating.”27 Stereotypical images of “passive femininity” present women with an unhealthy, underweight, and virtually impossible body image that many internalize and destructively pursue.

While eating disorders are certainly a significant problem for large numbers of women, research suggests that many men also suffer from body dysmorphia as a result of sexist media stereotypes. In 2000, Harrison G. Pope, Katherine A. Phillips, and Roberto Olivardia published The Adonis Complex, bringing popular attention to male eating disorders for the first time.28 Though not an officially accepted medical term, the so‐called Adonis Complex is a catch‐all condition that refers to “an array of usually secret, but surprisingly common, body image concerns of boys and men.”29 These concerns include dissatisfaction with musculature, body‐fat ratio, and overall size, issues that often result in steroid use, unhealthy weightlifting practices, and eating disorders like anorexia and bulimia. The authors cite the increasing images of “perfect” men in the media as a significant cause of the Complex, demonstrating, for example, how sexually risqué images of men have steadily risen to be as common as images of women in popular women’s magazines. These representations, usually shown with slender waists, rock‐hard abs, and huge biceps, place pressure on individual men to live up to nearly impossible standards of masculinity. The Adonis Complex reveals that eating disorders resulting from media representations of gender are not just a problem for women. The active/passive gender binary gives rise to a culture of the figure where being “too big” is as deadly as being “too thin.”

The role of media texts in exposing consumers to impossible or unhealthy body types is certainly an important one to examine, especially when they result in harmful personal choices. It is also necessary, however, to understand how these texts influence the makeup of social institutions. Media representations are the result of cultural attitudes toward sex and gender, but stereotypes reinforce those attitudes and help shape them through workplace and government policies. One of the most apparent examples of the institutionalized discrepancy between the sexes is the issue of pay. In late 2017, an analysis of Census Bureau data conducted by the American Association of University Women revealed that women who work full time earn on average only 80 percent of what men earn, with older women, women from certain racial groups, and women with disabilities falling below this average. Though some of this discrepancy may be explained by the fact that women tend to enter lower‐paying fields that resonate with stereotypically feminine traits (including education and social work), even comparisons between the sexes within the same occupations reveal that women tend to earn less than men.30 In addition, women who attempt to enter the upper echelons of the working world by pursuing management positions often come up against the glass ceiling, or informal, gendered workplace policies that allow women to progress only so far in promotion. The logic is that women often lack the (traditionally masculine) qualities of assertiveness and rational thinking that management positions require. Media representations of femininity that position women as meek, subservient, or overly emotional thus contribute to a culture where it is permissible for women to earn less and have fewer occupational opportunities.

Finally, we would be remiss if we did not think about the ways that stereotypical images of femininity and masculinity contribute to a society that often presents a physical threat in the lives of individual women. The sexual harassment and assault scandals that rocked the American film, television, radio, and sports industries in 2017 and 2018 – as well as the resulting #MeToo movement, which proliferated through social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter – were notable reminders of the objectifying menace that many women face from men in their daily activities. Moreover, according to the most recent statistics collected by National Domestic Violence Hotline, women outnumber men as victims of domestic abuse today by almost every measure, with women ages 18–34 experiencing the highest rates of intimate‐partner violence.31 These examples suggest that for whatever social and political advancements women have made as a group through the 21st century, many still suffer disproportionately and unfairly as a result of their sex. While we do not suggest that the circulation of stereotypical images of gender actually caused or created such a social milieu, it is difficult to deny the powerful resonance between popular images of sexually available women and sexually pursuant men and the increasing social prevalence of sexual abuse.

Conclusion

Throughout this chapter, we have looked at how media representations of sex and gender contribute to social systems of unequal power distribution. Though contemporary Feminist analysis is a highly complex and varied critical tradition, we have addressed some of the major issues regarding representation that this approach contributes to the field of media studies. Media representations of men tend to define masculinity according to power, agency, rationality, and sexual prowess, while images of women mark femininity according to passiveness, domesticity, emotion, and beauty. It is the goal of Feminist analysis to deconstruct popular media texts to reveal this narrow framing and the systems of inequity that it supports. At the same time, feminists remain wary of postfeminist sensibilities that too quickly proclaim the end of patriarchy and the primacy of female individualism and choice. These competing interpretations of gender in contemporary society give rise to confusing, often contradictory messages about the various roles of men and women. Feminist analysis, then, is also a way of beginning to untangle these texts and tease out their social, cultural, and political implications.

Because feminism has often unfairly garnered the reputation of being anti‐male, we wish to conclude this chapter by again reiterating that stereotypes of both femininity and masculinity are damaging to individual media consumers in everyday life. Everyone suffers when skewed media stereotypes become the basis for social interaction. Though patriarchal systems of power ensure that representations of women are more restricted and harmful, even representations of men encourage limited modes of action and identification for individual males. Thus, it is in everyone’s interest to participate in the types of analyses outlined by Feminist scholars. It is only by interrogating all constructed representations of gender and sex that we can move beyond the harmful social structures that characterize contemporary life.

SUGGESTED READING

- Bell, E., Haas, L., and Sells, L. (eds.) From Mouse to Mermaid: The Politics of Film, Gender, and Culture. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1995.

- Bordo, S. Unbearable Weight: Feminism, Western Culture, and the Body. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1993.

- Butler, J. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity, 10th anniversary edn. New York: Routledge, 1999.

- Carter, C., Steiner, L., and McLaughlin, L. (eds.) The Routledge Companion to Media and Gender. New York: Routledge, 2015.

- Cepeda, M.E. Beyond “Filling in the Gap”: The State and Status of Latina/o Feminist Media Studies. Feminist Media Studies 2016, 16, 344–60.

- Collins, P.H. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. New York: Routledge, 2000.

- Connell, R.W. Masculinities. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1995.

- Dow, B. Prime‐Time Feminism: Television, Media Culture, and the Women’s Movement Since the 1970s. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1996.

- Haraway, D.J. Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. New York: Routledge, 1991.

- Hernandez, D. and Rehman, B. (eds.) Colonize This! Young Women of Color on Today’s Feminism. New York: Seal Press, 2002.

- hooks, b. Feminism is for Everybody: Passionate Politics. Cambridge, MA: South End Press, 2000.

- Johnson, D. and Swanson, D.H. Undermining Mothers: A Content Analysis of the Representation of Mothers in Magazines. Mass Communication & Society 2003, 6, 243–65.

- Kaplan, E.A. (ed.) Feminism & Film. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Katz, J. The Macho Paradox: Why Some Men Hurt Women and How All Men Can Help. Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks, 2006.

- Krijnen, T. and Van Bauwel, S. Gender and Media: Representing, Producing, Consuming. New York: Routledge, 2015.

- Laqueur, T. Making Sex: Body and Gender from the Greeks to Freud. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990.

- Loke, J., Bachmann, I., and Harp, D. Co‐opting Feminism: Media Discourses on Political Women and the Definition of a (New) Feminist Identity. Media, Culture & Society 2017, 39, 122–32.

- Mann, L.K. What Can Feminism Learn from New Media? Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies 2014, 11, 293–7.

- Massanari, A. #Gamergate and The Fappening: How Reddit’s Algorithm, Governance, and Culture Support Toxic Technocultures. New Media & Society 2017, 19, 329–46.

- McLaughlin, L. and Carter, C. (eds.) Current Perspectives in Feminist Media Studies. New York: Routledge, 2011.

- Moraga, C. and Anzaldua, G. (eds.) This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color. New York: Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, 1984.

- Radner, H., and Stringer, R. (eds.) Feminism at the Movies: Understanding Gender in Contemporary Popular Cinema. New York: Routledge, 2011.

- Savigny, H., and Warner, H. (eds.) The Politics of Being a Woman: Feminism, Media and 21st Century Popular Culture. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

- Smith‐Shomade, B.E. Feminist Media Studies and Community. Communication Review 2015, 18, 7–13.

- Tasker, Y. and Negra, D. Interrogating Postfeminism: Gender and the Politics of Popular Culture. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007.

- Webber, B.R. (ed.) Reality Gendervision: Sexuality and Gender on Transatlantic Reality Television. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014.

NOTES

- 1 D. Sims, The Ongoing Outcry Against the Ghostbusters Remake, The Atlantic, May 18, 2016, https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2016/05/the‐sexist‐outcry‐against‐the‐ghostbusters‐remake‐gets‐louder/483270/ (accessed September 15, 2017).

- 2 R. Keegan, How Misogyny Impacted ‘Ghostbusters’ Opening Weekend – And its Future, The Los Angeles Times, July 19, 2016, http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/movies/la‐et‐mn‐ghostbusters‐reaction‐column‐20160715‐snap‐story.html (accessed September 15, 2017).

- 3 b. hooks, Feminism is for Everybody: Passionate Politics (Cambridge, MA: South End Press, 2000).

- 4 A. Stone, An Introduction to Feminist Philosophy (Malden, MA: Polity, 2007), 43.

- 5 N. Richardson and S. Wearing, Gender in the Media (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), 1.

- 6 A.G. Johnson, Privilege, Power and Difference, 3rd edn (New York: McGraw Hill, 2018), 71–2.

- 7 A.E. Dastagir, You’re Sexist. And So Am I, USA Today, June 8, 2017, https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/2017/03/23/everyone‐is‐sexist‐internalized‐sexism/99528476/ (accessed September 2, 2017).

- 8 I. Molina‐Guzmán and L.M. Cacho, Historically Mapping Contemporary Intersectional Feminist Media Studies, The Routledge Companion to Media and Gender, C. Carter, L. Steiner, and L. McLaughlin (eds.) (New York: Routledge, 2015), 79.

- 9 T.E. Perkins, Rethinking Stereotypes, in Turning It On: A Reader in Women & Media, H. Baehr and A. Gray (eds.) (New York: Arnold, 1996), 21.

- 10 R. Dyer, Stereotyping, in Media and Cultural Studies: Keyworks, revised edn, M.G. Durham and D.M. Kellner (eds.) (Oxford: Blackwell, 2006).

- 11 T. Linn, Media Methods that Lead to Stereotypes, in Images that Injure: Pictorial Stereotypes in the Media, 2nd edn, P.M. Lester and S.D. Ross (eds.) (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2003), 23–7.

- 12 K. Walsh‐Childers, Women as Sex Partners, in Images that Injure: Pictorial Stereotypes in the Media, 2nd edn, P.M. Lester and S.D. Ross (eds.) (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2003), 141–8.

- 13 S. Bordo, The Male Body: A New Look at Men in Public and Private (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1999).

- 14 L. Nemecek, The Star Trek: The Next Generation Companion (New York: Pocket Books, 1992), 13.

- 15 S. de Beauvoir, The Second Sex, trans. H.M. Parshley (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1952), xix.

- 16 N. Wolf, The Beauty Myth (New York: William Morrow and Company, 1991), 12.

- 17 S. Thornham, Women, Feminism and Media (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), 16.

- 18 R. Gill, Postfeminist Media Culture: Elements of a Sensibility, European Journal of Cultural Studies 2007, 10(2), 147–66.

- 19 Gill, 154.

- 20 See B. Dow, Prime‐Time Feminism: Television, Media Culture, and the Women’s Movement Since the 1970s (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1996); A. McRobbie, Post‐Feminism and Popular Culture, Feminist Media Studies 2004, 4(3), 255–64.

- 21 McRobbie, Post‐Feminism.

- 22 S. Becker, D. Thoman, and M.R. Cope, Post‐Feminism for Children: Feminism “Repackaged” in the Bratz Films, Media, Culture & Society 2016, 38(8), 1218–35.

- 23 Becker et al., 1232.

- 24 S.E. White, N.J. Brown, and S.L. Ginsberg, Diversity of Body Types in Network Television Programming: A Content Analysis, Communication Research Reports 1999, 16(4), 386–92.

- 25 J.A. Reade, The Female Body on Instagram: Is Fit the New It?, Reinvention: An International Journal of Undergraduate Research 2016, 9(1).

- 26 S. Bordo, Unbearable Weight: Feminism, Western Culture, and the Body (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1993), 190.

- 27 J. Kilbourne, Deadly Persuasion: Why Women and Girls Must Fight the Addictive Power of Advertising (New York: The Free Press, 1999), 116.

- 28 H.G. Pope, Jr, K.A. Phillips, and R. Olivardia, The Adonis Complex: The Secret Crisis of Male Body Obsession (New York: The Free Press, 2000).

- 29 Pope et al., 6–7.

- 30 American Association of University Women, The Simple Truth About the Gender Pay Gap (Washington, DC: AAWU, 2017).

- 31 Get the Facts & Figures, The National Domestic Violence Hotline, http://www.thehotline.org/resources/statistics/ (accessed January 5, 2018).