CHAPTER 11

LEARNING THE LEGEND

We are not afraid to entrust the American people with unpleasant

facts, foreign ideas, alien philosophies, and competitive values.

For a nation that is afraid to let its people judge the truth and

falsehood in an open market is a nation that is afraid of its people.

— JOHN F. KENNEDY

In part II of this book, you learned how the brain processes senses into feelings and feelings into thoughts. In part III you learned that we can guide those feelings through techniques like anchoring, future pacing, the learning trance, and framing. With each code you crack, you have moved from being an unconscious communicator to a conscious one and from being an incompetent communicator to a competent one.

The next and last step to cracking the code is to become an unconsciously competent communicator. As such you will master the art of political persuasion as well as the science. Once you master this last section of the communication code, you will move from being able to persuade the person sitting next to you to being able to persuade large groups of people.

When we move from persuading a single individual to the much larger and more complex task of political persuasion, we need a whole new set of tools. Unconscious competence requires understanding not only how the communication code works but also why it works. Without understanding the why, even competent communicators can fail to persuade. The abortion debates of the 1980s and 1990s provide a useful example of two competent attempts at communication around the same issue and why one worked better than the other.

PRO-LIFE OR PRO-CHOICE?

Through the 1980s and 1990s, one of the defining issues for both liberals and conservatives in the United States was abortion. Republicans had trouble winning elections if they were in favor of a woman’s being able to decide whether or not to have an abortion. Democrats had trouble winning elections if they were against a woman’s right to choose to have an abortion. The abortion debate provided voters and pundits with a kind of litmus test.

As an issue, abortion naturally triggers deep-seated feelings, and the word abortion itself triggers mainly negative emotions. How we feel about a word or an idea largely determines how we think about it. Because the word abortion is such a powerful negative anchor, advocates of legalizing abortion needed a different way to talk about this issue that affects women and their bodies. In 1973, just after Roe v. Wade made abortion legal, feminists found the frame they had been looking for: “pro-choice.”1

This was a time in America’s history when women were demanding the right to be treated as equals to men under the law. Even though American women won the vote in 1920, many laws were still stacked against women. It was not until 1963 that women won the right to equal pay for equal work (Equal Pay Act), 1964 that women won the right to not face discrimination in the workplace (Civil Rights Act), and 1965 that married women won the right to legally use contraception (Griswold v. Connecticut). The rallying cry of the feminist movement in the 1960s and early 1970s was that women were equals to men and had the right to choose what to make of their lives and what to do with their own bodies.

“Pro-choice” was a potent frame for those who felt strongly about a woman’s right to equality with men. The frame “prochoice”appeals at a gut level to anyone who believes that all people have certain inalienable rights. It’s a frame that ties directly into the words of this country’s Founders, who declared that each of us has the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

Within a year after the “pro-choice” frame appeared in print in 1975, however, opponents of legalizing abortion struck back with a frame of their own: “pro-life.” “Pro-life” had for years been the frame used extensively by the mainly liberal anti-death penalty movement. Abortion opponents took that “pro-life” frame and repurposed it as a “forced pregnancy” frame.

Both “pro-choice” and “pro-life” are strong frames. Yet a woman’s right to choose whether or not to have an abortion, when, and under what circumstances, has been decaying since Roe v. Wade. More than forty states now have a ban on late-term abortions.2 In thirty-three states, teenagers cannot obtain a legal abortion without parental consent or parental notification.3 The number of U.S. abortion providers declined by 11 percent between 1996 and 2000 (from 2,042 to 1,819). Eighty-seven percent of all U.S. counties lacked an abortion provider in 2000. These counties were home to 34 percent of all 15- to 44-year-old women.4 In the battle of the frames, “pro-life” is winning. Why?

UNDERSTANDING THE WHY

In part III we talked about how the meaning of a communication is the response you get: what matters is not what I say but what my listener thinks I said. We talked about ways to make sure that my listener would get my meaning. That’s one key to the communication code.

What we didn’t talk much about, however, is why communication works this way. Why don’t other people see or hear or feel the world the same way I do? Don’t we all see, hear, and feel the same things? If we walk into a room with a desk and a chair,don’t we all see a desk? If we sit down, don’t we all feel the same padded cushion?

The answer, in short, is no. We don’t. We don’t all see exactly the same thing, and we don’t all feel that cushion in exactly the same way. There really is a desk and a chair in the room, but each of us experiences that desk and chair differently.

Let me give you an example from my own life. I live on a houseboat on a river. That’s the territory I live in. “Territory” can be used to describe any part of the physical world. A room with a desk and a chair is a territory, for example. And “territory” can also be used to describe our psychological and political worlds (more on that shortly).

I can describe to you where I live—my territory—even if you are not here with me. Right now, sitting in my houseboat, looking at the river, I can tell you that the water is brown/blue/greenish, there are ripples, there are ducks along the bank, and so forth. My description of the river becomes a map of the territory for you. You are not experiencing the territory yourself, but you can experience my map of it.

Now, what happens if you come to visit me? What if you and I are standing on my dock, looking at the river together?

We are looking at the same territory, the river. We both can see the blue heron fishing on the riverbank, feel the cool-water breeze, and smell and hear the water as it flows around the pilings on which our dock and home float up and down with the tides. We can discuss the river and share what we each see and hear and feel. But here’s a secret that most of us know but never really accept. It’s the secret that will make you an unconsciously competent communicator:

Even though we are both experiencing the same territory, our individual experience of that territory will always remain different.

When we both stand and look at the river together, we both notice and experience different things. I might be knowledgeable about trees and see beech trees and willows, whereas you see just trees. You might like to fish and will know where they’re most likely to be found, seeing those places that I don’t even know exist.

We also come with different emotions that change how we understand our sensory experiences. I might have memories of this river that color my feelings about it and how I see it—and those are memories and feelings that are different from yours. Your experience of rivers in the past is certainly different from mine. Because our senses are tied to our emotions and memories, and mediated by our individual nervous systems, we will never see or hear or smell or taste or feel things in exactly the same way as another person.

We already know this. One of our kids loves peppermint ice cream; the other kid hates it. Same ice cream, different experience.

One person listens to a Beethoven symphony and hears patterns of sound; another hears a story; another is bored and tunes out.

We have these experiences of our differences among each other all the time. It’s what makes life so rich and interesting.

Those differences have significant consequences, however, for communication. Anytime we communicate, we are never going to be successful at giving people a pure experience of objective reality—the territory.

No matter how well I describe my river to you, my map of the territory will never match your map of the territory. And neither map is the territory!

DISTORTION, DELETION, GENERALIZATION

There is a reason why our maps usually don’t match up. We put our sensory experience of the world through three different kinds of filters: distortion, deletion, and generalization. Our brain instantaneously and continuously uses these filters to be more efficient in our communication and our experience of the world.

As you read this book, you are engaged in these three kinds of filters. Until you read this sentence, you were probably not aware of what is on the wall to your left or the temperature in the room. You deleted that experience—and you will delete it again by the time this chapter is over—because our minds simply can’t process more than five to nine things at once.

You’re also distorting your experiences right now. In distortion we misrepresent parts of reality, often as a way of simplifying experience. We almost always distort our memories of events because we file those events in ways that make the most emotional sense to us (remember the Pentaflex folders) rather than according to what our senses actually told us at the time.

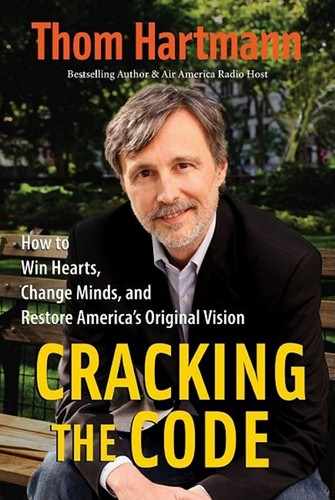

We also distort and generalize when we make assumptions about others. You may have made a whole set of assumptions about what was in this book when you read the title, Cracking the Code, or when you saw that “Thom Hartmann, Air America Radio host” was the author, or that I was on a Vermont roster of psychotherapists and once was the executive director of a residential treatment facility for abused and emotionally disturbed children, or that I was an advertising industry executive and consultant, or that I’m the author of more than twenty books and an entrepreneur, or that I did international relief work on and off for more than twenty years on five continents in several war and conflict zones, or that Louise and I have been married for thirty-five years and have three grown children and four cats, or that doing all of these things pretty easily qualifies me as a poster child for attention deficit disorder. Each evokes a frame, and each frame is filled with shorthand distortions, deletions, and generalizations.

You’ve also been generalizing your experience of the place you are in as you read this book. We don’t have enough time or energy to analyze every object we see that has four legs. We generalize and say to ourselves, that is a chair, this is a table. Right now you may be aware that you are in a room, or on a plane, or wherever you happen to be, but you are not paying attention to all of the details that make up the place you are in. You did not spend time thinking about the floor, the walls, or the objects in the room before you decided that you were in a room. To get through life, most of the time we have to label the world around us without thinking about its specificity.

Deletion, distortion, and generalization are necessary filters that enable us to process and make sense of the tremendous amount of information available to our senses. Yet when using these filters, we also sometimes delete, distort, or generalize in ways that may not be appropriate or useful. We may lose information we need, or we may misapprehend information.

When I tell you about the river I am looking at, my map of the territory has been filtered through my deletion, distortion, and generalization process into language. That is, the map I describe to you is already not the territory. It’s just a generalized and distorted version of my map, filled with deletions and handed to you in the form of words. (Forgot to mention that eagle in the tree on the riverbank, didn’t I?)

When I communicate that map to you, I communicate through language. That language is then filtered by you through your own internal deletion, distortion, and generalization process into your map. Your map is, in turn, a deleted, distorted, and generalized version of my map, which is in turn a deleted, distorted, and generalized version of the territory.

You may think when I describe the river to you that you are getting the territory, but you’re not. All we can ever get from another person is a deleted, distorted, and generalized version of their map.

MAP VERSUS TERRITORY

Let’s make the metaphor solid and talk about a Rand McNally highway map. As children learn in grammar school, a map’s code is necessary to read and make sense of a map. That code is called the legend. It’s a nice metaphor, legend, because the map’s code really is the story of the map, and it tells us how the map was created.

For example, if I am going to drive from Chicago to Ames, Iowa, I will look at my road map, which will show me which roads to take. But if I want to know what kind of roads they will be, I have to look at the legend, which will let me know that expressways are red, highways are bolded black, and 2-lane country roads are thin black lines.

If I want to know how long the journey will take, I have to consult the legend again, which may tell me that 1 inch on the map equals 50 miles. I can measure the inches, multiply by 50, divide by my driving speed (which I won’t reveal here!), and figure out how long it will take me to get from Chicago to Ames.

Geographers study the stories that maps tell. They can discern how people think about their world by the kinds of maps they make. Christopher Columbus, for example, had a map of the world in which Europe was at the center, and all the places he visited were “discoveries” because they had never been known to Europeans before. The people living in those places had their own maps, telling themselves stories about the relationships between their people and the many other people who they knew lived on the land. For them the Europeans were a discovery that necessitated new maps. And for every culture in the world, the center of its map was the center of its living space (so much so that during the Middle Ages in Europe, people who suggested that the Earth wasn’t at the center of the universe were put to death).

Think about how you would map your neighborhood. One map is the satellite map, showing how your home looks from outer space. Another is a road map of your city or county that shows all the streets near you but doesn’t show your house at all. A third map is the computer map your friend uses to get to your house, which may show streets or may be just a list of directions. A fourth map is the map of real estate values, which becomes very important when you want to sell your house. A fifth map is the map you carry around in your head of your neighbors—who lives next to you, who lives across the way from you, and so forth. You may even have a map of everyone’s dog, if you are a dog owner, or a map of all the playgrounds in the neighborhood if you have young kids.

Which of these maps is the map of the territory? All of them and none of them. Each map engages in deletion, distortion, and generalization. What makes these maps valuable to us isn’t whether they accurately represent the territory but how useful they are to us. If I don’t have kids, I probably don’t care where the playgrounds are. If I rent, I probably don’t care about real estate values. I may not care what my house looks like from outer space. What matters to us is what story a particular map can tell us—the story of who lives nearby, or what our financial value is, or how someone can find us.

It helps to remember that the code for maps is called a legend. The key to unlocking any map is the story the map tells. That’s true for communicative maps as well. What matters isn’t how accurate the map is—because no map will ever accurately reflect the terri-tory—but rather how useful it is.

MAKING A CHOICE

It’s a challenge to accurately communicate information about the physical world—the world that actually exists. It’s an even bigger challenge to communicate about the political world, which is essentially a series of abstractions used to describe processes that have an impact on the real world. The maps we create of these processes are always very different from the territory, which is precisely what is going on in the abortion debate.

What kind of story does the “pro-choice” frame tell? “Pro-choice” tells the story of modern feminism. For hundreds of years, women struggled for the ability to make their own choices. They struggled to own private property. They struggled to get the vote. They struggled for equal pay. “Pro-choice” reminds us that the right to a safe and legal abortion is the next step in that long story of women’s struggles for their rights.

That is a very powerful and inspiring story—for liberals. For women who want to assert their rights, and for men who support those women, “pro-choice” is an uplifting reminder that women have succeeded before and can succeed again. For those who embrace this story, it may also remind us of the Founders’s struggle to secure from the king of England the rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. It may remind us of the Civil Rights Movement and the Gay Liberation Movement and the many other movements of the 1960s that were about giving people the right to choose their destiny.

“Pro-choice,” in short, is a very powerful story for people who already believe in women’s right to equality with men and thus their right to decide whether they want to have access to a safe and legal abortion. The task of this particular frame, however, is not just to mobilize progressives who already support Roe v. Wade but to persuade those who are undecided or opposed to abortion rights. In that, the frame fails.

The main reason why it fails is because conservatives tell a very different story about the 1960s leading up to the 1973 Roe v. Wade Supreme Court decision. For them that era marked a time when the country lost its moral compass. Their story about America is not one of progress but one of decay. The source of their motivation, as we discuss in the next chapter, is fear rather than hope. So a story about hope doesn’t speak to them.

Many conservatives also don’t hold as a primary value the idea of living in a society in which everyone has choices. They believe in the dominator model—that some people should be the “deciders” and that others should do what the “deciders” say. Conservatives who are members of the religious right in particular tend to believe that men are the deciders and that women should abide by their decisions.

For example, I did my radio program live from the Republican National Convention in New York in 2004. A leading proponent of forced pregnancy sat in front of me and said that abortion at any time, under any circumstances, was murder.

“Isn’t it a capital crime to commission murder?” I asked.

“It is,” he said. “Women who hire an abortion doctor are just as guilty.”

“Well,” I said, “the penalty for murder, or hiring murder, is death in many states. Do you think women who have abortions should be executed by hanging, by firing squad, by lethal injection, or by gas chamber?”

Without missing a beat, he said, “That’s up to the states to decide what method of execution they are going to use.”

Choice, for him, is a symptom of what is wrong with this country. The “pro-choice” frame is not a map that is useful to conservatives.

On the other hand (and ironically), the framing words that conservatives chose for the abortion debate make a lot of sense to liberals.

The conservatives chose to frame their support for legally enforced pregnancies as “pro-life.” “Pro-life” tells a much simpler story than “pro-choice.” The “pro-life” frame tells us that every single human being is valuable, which is a very positive message. And it suggests that the world is divided into two kinds of people: those who are pro-life and those who are pro-death. It’s not hard to choose which side anybody would rather be on, particularly after the anti-death penalty movement had used the “pro-life” frame for more than a century.

Now, you may say, hold on, the conservatives’s map is not accurate. The same people who say they are “pro-life” about abortion are often in favor of the death penalty; many were in favor of the war in Iraq, and some don’t even care if the life of the pregnant mother is at risk because of the pregnancy. The forced-pregnancy crowd may be a minority, but they are loud enough to appear numerous.

This highlights how the effectiveness of a map is based on usefulness, not accuracy, in part because no map is totally accurate.

If I’m trying to drive to my friend’s house, it doesn’t help me to have a map of the real estate values on the block or of the location of kids’s playgrounds. I’d be better off with directions that delete, distort, and generalize about those things so long as the map does tell me what street my friend lives on.

The conservatives’s forced-pregnancy map deletes the many situations in which its proponents actually favor death. It distorts the many side effects of their position, one of which is that some women will die if abortion is not safe and legal. It generalizes from one particular medical procedure to a broad worldview. It implicitly embraces the notion that women are weak and emotionally and mentally inferior to men and thus in need of the protection and the guidance of men (and, by proxy, government run by men). Neither the “pro-life” nor the “pro-choice” map accurately represents the complex and multifaceted terrain of the abortion issue.

The “pro-life” frame succeeds as a map, however, because it modifies the territory in a very powerful way. Whereas the “pro-choice” frame suggests only that people who are opposed to abortion are opposed to women having choices, the “pro-life” frame suggests that people in favor of a woman’s having access to safe and legal abortions are also in favor of murder.

The “pro-life” frame suggests that anyone who does not embrace pro-life supports death. Because no one supports death, they must, de facto, support life and thus be against abortion. Once you get into the “pro-life” frame and accept the pro-life story, there is no way out, no room for discussion.

The pro-life map is accurate only for those whose territory is defined by certain religious or social perspectives, but it is useful for them. The same can be said for the pro-choice map. The story is all in the telling. Those who control the map will define and ultimately control the territory. In fact, the map is more than just useful. The pro-life map actually controls the story.