Chapter 24

Call Signs, Slogans, Jingles, and Characters: The Bits and Pieces of Broadcasting

For broadcasters, disputes over call signs, slogans, jingles, and characters can be the most intense and important encounters with copyright or trademark law. They mark the media outlet's public persona and reputation. Since imitation of the leader is not only great flattery but also an effective way to compete, a competitor's taking of key trademarks usually signals a strike at the heart of a broadcaster's base.

Call Sign Disputes

The FCC is the agency that grants call letter assignments. With tens of thousands of broadcast facilities, finding a combination of letters that also creates an acceptable image or theme is not always an easy task. While the FCC assigns letters to stations for new facilities on a random and arbitrary basis, stations can request preferred allocations. The key obligation is to limit call letters beginning with W to stations east of the Mississippi and K to stations west. The three remaining choices among the 26 letters of the alphabet permit a wide variety. Many stations try to link their call sign to some theme or format; so an oldies station might go for WSGH—Solid Gold Hits or a regional channel might apply for KGLB, Great Lakes Broadcasting.

Touchy subjects arise when two competitors in the same market, whether in the same city or in an urban-suburban relationship, have call signs with similar visual, rhythmic, or phonetic elements; for example, WSGH and WSGA or KGLB and KGLP. Until the mid-l980s, the FCC handled these disputes. Then, in a policy statement, it indicated that it would allow the disputes to be treated like all trademark conflicts, by resort to negotiations between interested parties and, if necessary, filings in court. Stations have taken up the challenge, and a number of call sign disputes have ended up in the courts. As a result, trademark rules apply to call letter disputes.

A spin-off issue involving call letters is the impact of relinquishing call signs when format or management changes. Call signs of long standing in a community may be relinquished for FCC purposes, but the issue is, who is free to pick them up? Since call signs can be registered with the PTO as trademarks, does a change in call letters constitute abandonment for trademark purposes, allowing anyone to use the letters? This issue has never been resolved in court, but creative broadcast managers can do a few things to protect themselves against an archrival taking released call letters and trying to get a competitive lift.

First of all, register the call letters with the PTO. Federally registered trademarks stay on the books for up to 10 years. Abandonment of trademarks requires active intent. If a station can demonstrate that, even though the call sign has been released, there is still a long-standing local recollection of the phrase and a plan to use it, then it would be confusing in the community to allow an unrelated station to grab the call sign. Indeed, this time-honored trademark trick can be used by nonbroadcasters as well. For example, Exxon used this ploy to protect the mark Humble, seemingly abandoning the word following consolidation of all its trademarks.

Second, maintain some actual use after the change, including such helpful notice as ‘WGLB, formerly WSGH.’ Surveys have shown that the public remembers call signs long after they cease to be used in the market. Maintaining awareness could also help the people who keep diaries for rating services to locate the right station, even as the image of the facility is changing.

Third, sell the right to some other distant facility, or at least encourage a nonmarket station to take it over. Sometimes, call letters have a real market value for another and can be sold for a decent price. When Ted Turner converted Channel 17 into a cable superstation, he hunted around for another station with the initials of his company, TBS, and paid a handsome sum for the call sign WTBS. Moreover, with the elimination of rules prohibiting ownership of more than one television station in a given market (so-called duopoly rules) and the consolidation of station ownership, station owners may control dozens of radio properties, some in the same broadcast market. Swapping call signs within group owned stations can prevent call signs from being gobbled up by local competitors.

Slogans and Jingles

Slogans for media outlets are their key identification to the public. ‘News 4 You’ or jingles such as ‘Are You Ready for This? It's the Sports Blitz!’ are prime examples of stations selling an image to their viewers or listeners. In some cases, firms in the business of developing station image packages license subscribers the right to a slogan and related material, such as bumper stickers, video spots, jingles, onair personalities or voices, and the like in a specific market. This means that, as one travels around the country, other stations may have the same package. To the traveling public, there may seem to be a connection between the stations; however, the only link would be a common licensing source.

For stations, this permits an efficient way of capitalizing on a proven commodity. However, there are some things to keep in mind:

- Contracts. As a licensee, if a station varies the slogan package it might run afoul of the contract requirements. Since a licensor of slogans, or any trademark owner for that matter, needs to maintain quality control, stations are not free to modify the package without prior approval. Most often, artwork, use of the marks, and other key elements may not be changed without licensor approval. Read the license contract carefully before considering modifying the package.

- Ownership of changes. If a station develops a unique and successful edge to the licensed slogan, does it own the change? The answer to that question may not be as simple as one might expect. Look at the license agreement for starters. Even assuming a special stamp could be placed on the way the facilities use the slogan and other elements, the licensor may claim ownership of any changes under a variation of work made for hire. Before signing on, the station may wish to modify the license agreement to ensure ownership of the elements it develops.

- Facilities covered. Often, license agreements have strict limits covering the precise facilities to which they apply and the market within which they may be used. Especially for owners of several media properties, there is no guarantee that a successful slogan can be transported to another market. Read the agreement carefully, and, if plans call for using station 1 as a tester for sister facilities, make sure the agreement permits extension into other markets.

Characters

Especially in the radio business, on-air personalities create their own persona. Whether it is a cute name, an identifiable voice, or a musical interlude, there is a need for tangible identifiers with which the public can associate. Often, the people who let the rating services know what programs they are listening to or watching do not remember station call letters or precise time periods when they watch or listen, but they do remember a key character by name. Radio listeners may not know the station's frequency but remember they listened to Rush Limbaugh at 2 P.M.

In some cases, popular personalities are wooed to competitive stations. The issue that personality mobility raises is who owns the character. If we are dealing with someone's real name, absent extraordinary circumstances, the station to which the personality defects can refer to the individual and, if desired, call the show by his or her name. In some limited situations, a name may be so prominent that the original station might contract for its exclusive use in the market for a period of time. These agreements are disfavored because people should be free to use their own names in their chosen occupation. However, there may be a reason, such as a big up-front fee that the personality received from the original station, to justify setting a limit on what happens when he or she leaves.

In the case of fictitious names, the rules are more restrictive. Was the character or routine developed by the person under a work-for-hire arrangement? If so, the employer owns the work product of its employees and has a right, not only to prevent a defecting employee from using the fictitious name at the new station, but also to allow a replacement employee to use it at the home station. When an on-air personality known as Mr. Frank 0. Pinion left one St. Louis radio facility for another, the tussle over rights to the names hit the front pages of the local newspapers. The originating station retained its rights by early contract protection. As we saw in Chapters 10, when David Letterman jumped from NBC to CBS, the fight over his Top 10 segment also made headlines. It behooves all media outlets that encourage the development of themes and characters to look closely at the ownership of these properties. Particularly in an industry where people move around frequently, not just from stations within a town but across states and the nation, defining who owns what can be difficult. If an on-air personality (DJ Donnie from Denver) adapts a routine made successful by another DJ (DJ Derbie from Dallas, Donnie's former city of employment), who owns what? Does DJ Derbie and his employer have a claim? You bet they do.

However, unless the preliminary work in protecting the copyright and trademark elements has been done, the rights entitlement becomes murky. DJ Derbie and the employer need to have adequate proof of first use, and these records may be hard to construct. Rarely is action taken when imitations are performed in a geographically distant market. However, if the second user (DJ Donnie) achieves regional or national prominence, the originator (DJ Derbie) may gnash his teeth because he failed to act. If Donnie reemerges in Derbie's market, the stakes automatically become higher, and the likelihood that the dispute will intensify increases.

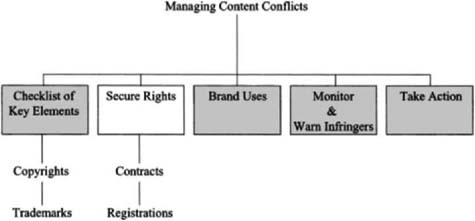

Here are a few handy hints for the creative media team that can be applied to many other situations and help prepare for these inevitable conflicts:

- Keep a checklist of the key on-air elements of the facility and rank them in order of importance.

- Determine what rights need to be secured and how: first by contract with all the participating parties, then by filing registration claims with the Copyright Office or the PTO.

- Brand intellectual property as copyrighted works or trademarks.

- For the valuable material, monitor the marketplace and warn would-be infringers, no matter where they are, that you will not permit theft of this property.

- Take action. Serve notice on the infringers and, if necessary, seek injunctive relief and damages under copyright, trademark, or unfair competition.

To repeat: you don't have to be in the media to follow these handy hints (Figure 24-1).

These elements are the bits and pieces of broadcasting. They are also the personality of the stations and the heart and soul of the media operation. They should not be taken for granted; if they are, sooner or later, they will simply be taken.