Chapter 5

Compulsory Licensing: Government's Helping Hand

A central part of the success of the cable industry was the creation of the cable compulsory license. This permission allows cable systems to deliver copyrighted programs to their subscribers; in exchange, they pay a fee set not by the marketplace but by the government. The payment is delivered to the Copyright Office, which then arranges for its distribution to copyright owners. This copyright policy compromise was essential in enabling the cable industry to move into the media big leagues. A similar compromise has, as we will see, helped the direct satellite industry assume a significant role in delivering content to the home (Figure 5-1).

To understand the tension in the compulsory license scheme, a brief bit of history is in order. In two important copyright cases in the 1960s and 1970s, the U.S. Supreme Court held that, under the Copyright Act of 1909, cable companies had no copyright liability to owners of copyrighted programs. During those days, cable principally retransmitted Federal Communications Commission (FCC)-licensed broadcast stations. The Supreme Court ruled that the cable operators were just like their subscribers; they were on the “viewer side of the equation.” Since “viewing” did not violate an exclusive right of copyright owners (check Chapter 3 if you disagree), there was no liability for the system operators with regard to the copyright interests when they delivered signals to subscribers.

These decisions caused a firestorm reaction in the programming community. In an era when cable television served less than 20% of U.S. television households, the medium was considered by some of its most vociferous critics as a parasite on the broadcast community's very being. The local television stations paid hefty fees to acquire programs, while cable operators freely took those signals and made a buck, simply by delivering them, unchanged but with a clearer picture, to households in the market.

When the FCC changed its rules in 1972 to allow cable operators to bring in distant signals (e.g., New York City stations to Albany, Pittsburgh, or New England), local broadcasters and movie companies screamed. Not only was cable taking the broadcast station's very signal and programs and making money off the retransmission, it was draining audiences from local affiliates with no legal obligations. The criticism mounted and reached reconciliation in Section 111 of the 1976 Act. The compulsory license created by this section has five main elements.

Cable's Duly to Pay Programming Sources

The compulsory license system recognizes that cable systems owe a copyright duty to the owners of content. That duty is satisfied by paying a fee fixed by statute for the retransmission of distant, nonnetwork programming. The fees were originally set by statute and are subject to revision every 5 years. If the interested parties cannot revise fees by mutual agreement, any change is left to Congress's designated agent (first the Copyright Royalty Tribunal [CRT], a federal agency created by the 1976 Act to manage compulsory licensing, then beginning in 1994, the Librarian of Congress). In addition, because the original fees were based on FCC rules in place when the 1976 Act was passed, any material changes to those 1976 FCC rules, expanding the scope of retransmission rights, could also trigger royalty changes.

In fact, FCC rule changes involving leapfrogging rules and syndex rules have required important rate adjustments:

- Leapfrogging rules are geographical limits on which signals could be imported by cable operators. The FCC had required the cable system to pick a nonnetwork signal from the city closest to it. By eliminating the closest city requirement, cable systems could choose independent signals originating in more distant cities, thus “leapfrogging” over a signal from a closer city. The CRT imposed a fee of 3.75% of a cable system's gross receipts based on each leapfrog signal and system imported.

- Syndicated exclusivity (syndex) rules are standards that require a cable operator to delete a program from a nonlocal station when it duplicates programs broadcast on a local station to which the local station has exclusive market rights. In 1981, when the FCC eliminated the syndex rules, cable operators were freed of the obligation to black out duplicated programming. A syndex surcharge, a 20% boost in fees, was added by the CRT.

- In 1990, after many broadcaster complaints, the FCC reinstated syndicated exclusivity in 1990 (more on this shortly). The CRT reversed its course and canceled the surcharge.

All these changes were important because, coupled with the increased popularity of cable, annual compulsory royalties rose from $10 million in 1978 to over $200 million by 1990. Since its inception, the cable license has generated billions of dollars in fees. Compulsory licensing means real money.

Local and National Network Signals Are Free to Cable

The compulsory license mandated that cable subscribers are entitled to receive local programming and national network programming free of any copyright charge. The winning argument was that, when cable acts as a mere conduit of programming otherwise available off the air, only aiding in reception by boosting signal strength, no copyright fees are due. Also, the legislators reasoned that national communications policy was advanced by ensuring that all U.S. households had access to the national networks: ABC, NBC, and CBS. With the arrival of new networks, such as Fox, WB, and UPN, the definition of network is being tested, but for the time being, only the original big three are free under the compulsory scheme.

Intermediary Conduits/ Including Telephone Companies and Satellite Resale Carriers, Pay No Fee and Have No Liability

When the copyright rules were originally developed, cable was an earth-bound system. Signals were picked up off the air by microwave relay operators or common carriers, which, through a system of point-to-point towers placed on tall buildings or mountaintops, retransmitted signals from the originating broadcasting station, via the towers to the cable systems' headends (central signal processing centers). The cable operator then delivered the signal into subscribers' homes by coaxial cable or wire. Although the terrestrial microwave links were instrumental in getting the signals to the system, they did not serve subscribers directly and made no change to program content. Because of this status, they were exempted from any copyright liability. Similarly, telephone companies whose facilities were also used to deliver signals to cable customers were defined as exempt under the compulsory copyright rules.

When Ted Turner, then owner of a struggling UHF station (WTBS, Channel 17 in Atlanta), looked at the compulsory scheme, he saw an opportunity to take his channel and make it available beyond Atlanta. At the same time, satellite transmission of broadcast signals—the microwave relay in the sky—had just become a reality. By uplinking WTBS to a stationary satellite 23,000 miles above the earth, the signal could be relayed down and received anywhere in the United States.

Elimination of the leapfrog rules led Turner and a few others to capitalize on a provision of the compulsory scheme that was developed with the old terrestrial and telephone technology in mind. Under Section 111(a)(3), a retransmitter that merely facilitated the delivery of signals to cable operators was exempt from any copyright liability. The resale carriers were viewed like truckers, who are merely consigned to pick up the programming from one place (say, Atlanta) and deliver it to another place (say, Los Angeles). When the FCC eliminated the leapfrog rules, a critical barrier to Turner's vision was eliminated. Within a few years, WTBS became a nationally distributed cable channel (along with WGN, Chicago, and WWOR-TV, New York), and the cable superstation was born.

The popularity of these signals did much to get cable into new homes. With the availability on these channels of programming different from or complementary to that available on local stations and the networks, television viewers saw a reason to subscribe to cable, more video choices. The attractiveness of cable increased as these superstation outlets became sources of unique programming. In the 1980s, Turner and his growing company bought sports teams such as the Atlanta Braves and the Atlanta Hawks and programming such as the MGM Film Library. This last acquisition, which cost over $1 billion, gave Turner more than 3,600 classic movies to use in developing programming choices on his expanding cable network empire.

The compulsory license does not apply at all to the hosts of nonbroadcast channels that developed during the past decade. Why? Because the movie channels (such as HBO, Showtime, Cinemax, and The Movie Channel), sports channels (such as ESPN and Home Team Sports), and variety channels (such as Discovery, The Weather Channel, Nickelodeon, FX, SciFi, USA, Lifetime, CNBC, and dozens of others) license programs directly from a few sources. Cable grew into the media force it is today because it established the ability to deliver something different, something more than three or four local channels. In the 1970s and 1980s, the capacity to deliver the distant off-the-air independent signals, thanks to the compulsory license, put cable on the map for good.

Royalty Distribution

Since its inception, the compulsory royalty scheme has generated several billion dollars for programming interests. The money is paid by cable systems to the Copyright Office twice yearly. Payments accompany a completed statement of account forms. For the larger cable operators, the form looks like a complex version of the IRS's 1040. Medium-sized systems file an abbreviated report, and tiny systems (with less than $300,000 in annual revenue) pay a fixed fee of about $60.

During 1978, the first year of the compulsory scheme, only about $10 million was collected. However, with the growth of cable subscriptions (from 20% of TV households in the early 1970s to almost 70% of such households by the year 2001), the royalty pool multiplied dramatically, reaching a high point of almost $200 million. Since 1998, with the change of WTBS's satellite service from a retransmitted broadcast signal to a full-time specialty cable network and the explosion of competing satellite service direct to homes (covered by its own compulsory license), cable compulsory royalties have slid to about $120 million annually. At the same time that cable fees slid by 40%, the satellite fees have grown to $75–100 million. In total, the cable-satellite royalties still generate more than $200 million a year.

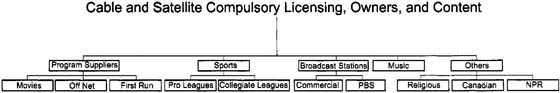

This bounty is divided among a core of avid claimant interests (Figure 5-2) in hotly contested royalty proceedings. The principal interests have been

- Program suppliers: film and syndicated programming distributors (first run and off-network).

- Joint sports claimants: major league baseball, the National Hockey League, the National Basketball Association, collegiate sporting interests, and other sports programmers.

Figure 5-2 Cable and Satellite Compulsory Licensing, Owners, and Content

- Commercial television stations.

- Public television stations.

- Music performing rights societies.

- Religious programming owners.

- Canadian broadcast stations.

- National Public Radio (NPR).

When the CRT was abolished in 1994, the victim of a lethargic administrative system and a Congress looking to shave costs, the royalty distribution responsibilities were transferred to the Librarian of Congress, with the mandate to empanel Copyright Arbitration Royalty Panels (CARPs) if the parties cannot privately agree on how to divide the royalties. The procedure requires each CARP to conduct a hearing and issue a report to the Librarian. The Librarian may accept or modify the recommendations of the CARP. Any final decision may be appealed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia.

Based on rulings of the CRT, the first CARP recommendation and the Librarian's ultimate decision awarded the majority of the royalties to the program suppliers, the film and television syndication industry. However, following a recent trend, the percentage award to the program suppliers dropped from almost three quarters to slightly over half. The biggest gainer during that period has been professional sports leagues, whose share has risen from about 15% to almost 30%. This reflects the strong influence of sporting events on cable subscriptions. The remaining share of royalties is split among the parties: commercial television receives about 7.5%, music performing rights societies 4.5%, public television 4%, and religious programmers and Canadian broadcasters about 1 % each. NPR has been gifted 0.18% by the parties, who have settled on an award for noncommercial radio, even though it was decided in the first royalty case that commercial radio stations were not entitled to any compulsory royalties.

Cable Prohibited from Altering Programming

At the center of the compulsory scheme was the precept that cable operators could not alter content or sell ads during retransmitted programming. The statute makes very clear that, with regard to retransmitted signals, there can be no alteration of programming or substitution of commercials by the cable operator. Local and distant signals must be carried in their entirety, without change, for the compulsory scheme to apply.

This makes good policy, but it has been tested by the syndex rules. In 1990, after years of studying commercial television's complaints about loss of market share to retransmitted, distant signals, the FCC reinstated the right of local broadcasters to demand that a program on a distant signal be deleted if the local station holds the exclusive right to air the syndicated program in its market (the syndex rules mentioned previously). Initially, only one super station, WTBS, had a “syndex-proof” signal, that is, national broadcast rights to all its programs. The other two primary superstations, WGN (Chicago) and WWOR-TV (New York) carried programs that local stations could force cable operators to delete. This created a real dilemma for many cable operators, who wanted to continue to deliver these popular stations to subscribers but did not want the hassle of deleting and substituting programs or, worse, carrying a channel with a blank screen during blackout periods. Such a situation would wreak havoc with the orderly scheduling of programs, impose a heavy administrative burden, and turn off subscribers.

To answer the problem, clever satellite resellers, firms in the business of picking up the broadcast signals off the air and relaying them to cable via the satellite, took advantage of a loophole interpretation of the compulsory licensing scheme. When WTBS became almost universally available to tens of millions of cable households, Turner sought to capitalize on the national reach by selling advertising on a national basis. Obviously, the charges for spot ads for a national cable audience of a million or more would greatly exceed the rates for a local Atlanta independent seen by only tens of thousands of viewers. To manage this two-tiered system, WTBS developed two ad rates, one for Atlanta only, and a second national cable rate. It then arranged with the satellite reseller to substitute commercials before the signal was uploaded on the satellite. If an advertiser wanted its advertisement seen only in the Atlanta market, Turner substituted a national spot when delivering the signal to the satellite firm. Because the substitution was done by order of the television station and not the cable operator or the satellite company, it did not run afoul of the compulsory license. And the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit so ruled.

With that decision in hand, enterprising satellite resellers moved to solve the syndex or blackout dilemma, which was even more complicated than the goal of achieving a split advertising system. By taking the WGN and WWOR-TV signals and substituting programming at the uplink site (at the request of the station), the carriers were able to qualify for the compulsory scheme when the local, regular WGN and WWOR-TV programming aired. And when the syndex-plagued programming arrived, they substituted programs for which they acquired national rights. This activity rejuvenated many old programs unseen for years, such as The Jack Benny Show and The Lawrence Welk Show. In the intervening years, the cable superstations, relying on the advertising advantage of reaching millions of cable subscribers, cleared their own facilities to contain more syndex-proof programming.

Satellite Statutory Licenses

Another twist for the satellite resale carriers led to another compulsory scheme in copyright law. Since the satellite retransmitted signal is available everywhere in the United States and most channels of cable programming migrated to satellite retransmission as the preferred mechanism for delivery, an industry selling huge satellite receiving dishes directly to homeowners burgeoned in the 1980s. The dish sellers offered people the ability to get cable programming without paying the monthly cable fees. Simply buy the dish and point it to the satellite, no cable hookups required. The practice also had appeal to restaurants, bars, and motels, which saw a cheap way (once the dish was paid for) to deliver programming to customers.

Needless to say, the practice created copyright controversy. To respond, in 1988 Congress passed a compulsory license just for home dish owners, the Satellite Home Viewer Act (SHVA). Under the scheme, noncable private homes using satellite receiving equipment could be licensed by satellite resale carriers. The carriers were obligated to collect royalties from the homes and pay them into a pool, which was managed initially by the CRT and then the Librarian of Congress.

Unlike the complex cable formulation, satellite rates are set at a fixed amount of cents per month per subscriber, based on the kind of signal received. Satellite services pay $0.06 per subscriber per month for network and educational signals, $0.175 per subscriber per month for independent signals, and $0.14 per subscriber per month for “syndex-proof” independents (those for which no deletions are required). While initially the amount of money generated by the SHVA was modest compared with the cable compulsory license, the system enabled many neglected television households in “white areas” (places where no off-the-air signals could be received and no cable exists) to benefit from local and national programming.

With smaller dishes, less-expensive equipment, hundreds of signals utilizing satellite transmissions, and a compulsory license, satellite resale carriers became a viable challenger to cable service operators by the year 2001, serving over 17 million homes. With this growth came the desire to make the service as functional as cable; however, unlike cable, the SHVA set limits on the number of distant network signals that could be imported. Late in 2001, a U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals upheld an FCC requirement that, if a satellite service offered a station from one market, like its cable competitor, it had to offer all the channels in that community. The local-to-local service requirement is the last piece in the puzzle to make satellite service a true alternative to cable. In February 2002, as part of the proposed merger of the two largest satellite carriers (DirecTV and EchoStar), EchoStar announced plans to deliver every broadcast signal in the country. This is no small task, and EchoStar conditioned its promise on approval of the merger proposition. (More about that plan in the discussion of antitrust issues in Chapter 17.)

Intense controversy developed, moreover, because the satellite compulsory system does not cover commercial establishments, such as bars, restaurants, and motels, which want easy access to the satellite programming. Concerned about the high fees associated with retransmission, many businesses resist paying top dollar rates and try to opt into the SHVA scheme. However, no broadcast station and no satellite carrier can authorize retransmission of programming owned by another, even though they have the right to deliver the content locally. The Copyright Act construes these for-profit uses, such as attracting customers to a sports TV bar, as requiring direct licenses. They are usually available from the program owner, even though they may be more expensive to secure than under the compulsory license.

An issue that appeared to be of major importance during the high-flying 1990s but was placed on the back burner with the telecom bust by the close of the 20th century is the entitlement of new players, such as telephone companies and other utilities, to a compulsory license. If the Baby Bells and other telephone operators or OSPs are to compete on an even playing field with the cable systems and satellite television for delivery of programming to the home, they must have access to the compulsory royalty scheme. Otherwise, they would have to greatly reduce offerings to subscribers who like particular broadcast channels. As could be anticipated, denying access to the compulsory license could leave the phone companies and OSPs hopelessly behind in the race to secure viewers. Although the Copyright Office requested comments on whether the phone companies qualify for the compulsory license, so far it has not given the green light to these companies.

Nevertheless, if the telephone industry, OSPs, or any other segment of the economy is ever to compete with cable and satellite companies in delivering television programming to the home, direct participation in the compulsory licensing scheme is essential. The compulsory scheme is part of the body and soul of cable. While it is an artificial marketplace that has few content-owning advocates, it provided a helping hand at a formative time for cable and remains a force essential to cable's rise in public popularity. Denying rights to the emerging media would place a potentially insurmountable barrier on the road to their success. Look for the compulsory scheme to apply evenhandedly to all new media.

Another compulsory license added by the DMCA is the sound recording license. As previously noted, we have more to say about that provision in the discussion of digital music rights in Chapter 32.