Chapter 10

What Is a Trademark?

While copyright law defines the rights and responsibilities regarding works, trademark treats the subtle arena of words, names, phrases, and symbols. In many ways, these linguistic and visual elements are the linchpins of relationships in the minds of people to the products and talents of creative professionals. Serving as source identifiers, trademarks allow the consumer to relate to a product or service based on a body of experiences or images. They are most fundamentally distinguished from copyrights by their brevity. While copyright law requires the element of originality and generally applies to works of at least 15 words, trademarks are often short and pithy. One word (Paramount), a string of letters (ABC), a short phrase (“All the News That's Fit to Print”), a visual design (the CBS eye), sounds (the melody of “When You Wish upon a Star”), colors (pink for fiberglass), or smells (high-priced perfumes) all constitute trademarks. They identify a source and embody a reputation.

Thus, TVs that say GE, movies stamped Universal, Internet access from AOL, clothing from Dior, bags from Gucci, gems from Tiffany, cable services from Comcast all have meaning to the public. The consumer relies on the information to help make choices in the marketplace; the trademark serves as the identity of the enterprise or individual. Picking a trademark is a way of defining who and what a business is all about.

Sometimes, marketplace competitors, searching for an advantage, play off the reputation of others. Whether by comparative advertising (Pepsi tastes better than Coke) or tricks to simulate logos, trademark issues dominate the efforts of many who seek to create a specific niche. Being savvy about trademarks smoothes the operation of any business enterprise.

The Internet and digital communications opened a whole new area for trademark exploitation. Domain names, metatags, and keywords are often shorthand for someone's trademark. We are constantly being bombarded with new uses of old marks. Even the right to use one's own name is being regulated in the interest of trademark protection.

Before delving into the key issues of trademark law, we look at the principal concepts that dominate this discipline.

Trademarks, Service Marks, Trade Names, Trade Dress, and Product Design

While we shall use the word trademark to cover all the types of elements, there are actually five terms that need to be distinguished. A trademark is a word or phrase physically stamped on a good or a label attached to a good. It is a unique identifier as to the source of the product. The product itself is tangible and can be held, lifted, eaten, or worn. Sometimes, the product is too big to fit into your pocket, like an automobile or airplane, but the word or symbol by which it is distinguished from competing articles is clear. Therefore, whenever the product is tangible, the relevant legal term is trademark.

A service mark is the word or phrase associated with the provision of services. Like a trademark, it is a unique source identifier. Since services are not tangible, you cannot touch them, eat them or wear them; yet, they are crucial to commerce and living. So, even though you cannot touch a communications service, you know the firms that deliver those services by these symbols: Verizon, AT&T, NBC, AOL-Time Warner, and KABC-AM and -FM. All these are service marks for the entities that provide communication services. Of course, the same symbol could serve as a trademark and a service mark: In the phrase AT&T long distance services, AT&T is a service mark, but when you reach for an AT&T telephone, the letters AT&T function as a trademark. In terms of legal treatment, there is no difference whatsoever between trademarks and service marks. This was not always the case, and indeed some portions of international law retain the distinction, but the practical effect for U.S. law is merely semantic.

Semantics, however, does not characterize the difference with trade names. A trade name is the actual name of a business, and it is readily identified by additional words, such as Company, Corporation, Ltd., LLC, or Inc. A trade name often comes attached to a street address, a phone number, or an e-mail address. Unlike a trademark or service mark, which is linguistically an adjective that modifies a type of good or service, a trade name is grammatically a noun; it identifies a particular person or business. A trade name can be converted into a trademark, as it is when AT&T Inc. stamps AT&T on one of its telephones.

Trade dress is a concept that has taken on great significance in recent years. Trade dress refers to a product's packaging or a business's overall image. The U.S. Supreme Court explained that the marketplace appearance of the Mexican restaurant Two Pesos (from the novel architecture of its building, to the uniforms worn by its wait staff, and the design of its menus) constituted the company's trade dress. In another case, the label on a bottle of booze was held to be distinctive trade dress. In short, trade dress is the total, unique image of a product or the enterprise providing services. While it may include individual elements that themselves are trademarks (e.g., a bottle of soda may have the mark Coca-Cola, along with the red stripe or a well-known bottle shape), it is the totality of the elements that makes trade dress. As with other source signifiers, trade dress can be exclusively claimed by its owner.

Product design is a related concept that became the subject of a more recent U.S. Supreme Court decision. In a case involving a clothing designer's stylistic line of children's garments that were imitated in low-priced outfits sold at Wal-Mart, the Supreme Court was asked to pronounce whether the design of a product was inherently distinctive (i.e., a source signifier) and functionally a trademark. Despite its declaration a few years earlier that trade dress could be inherently distinctive, the Supreme Court said that that could not be the case with product design. Even though the design of a product might become a trademark if it achieves great public familiarity (in trademark parlance secondary meaning), the Supreme Court explained that a product's design could never be inherently distinctive.

In this case the product design was clothing, but the potential kinds of product designs—particularly those made by creative artisans—are actually infinite; if you doubt this, just wander around a craft fair and look at the various practical creations, salt and pepper shakers in the shape of a dog and cat or a pair of chopsticks with a connecting flexible bridge. For the Supreme Court, the bottom line is a bright-line test: While the trade dress of a product or business can be inherently distinctive with no special legal showings, a product's design never can be. The decision requires that public association of a product's design with its designer as a unique source must be shown; however, the creator may turn to other bodies of law for some relief. If a product's design has original, expressive elements, copyright law may grant relief. Thus, even though the children's clothing designer may have a hard time proving that the public readily identified her as the sole source of the garments, if she had registered the clothing design as copyrighted work, then at least she could claim protection against direct copying.

As you now know, both a trademark and a copyright can be owned exclusively. However, the nature of the legal rights differs in two key respects, and those differences have important implications for competition. First, even though the term has been extended several times in recent decades, copyrights are granted for “limited periods of time.” At the conclusion of the term, the rights cease. Trademark rights, by comparison, need never end. As long as a mark is in use in commerce, the owner's interest continues. If the owner stops using a mark for a number of years, then the rights may be extinguished, but even short periods of inactivity do not terminate trademark rights.

Second, the copyright law is designed to prevent copying. If two people independently create the same work, with minor variations or even none at all, each can hold a copyright in his or her work and use it to the full extent of the law unless copying is proven by one or the other. While fair use and other limitations sanction certain uses of a copyrighted work without consent of the owner, the similarity of those works, in and of itself, is not dispositive of the legal question of infringement. Trademarks, by contrast, are monopolies on a word or phrase, with no regard to the independent creativity of a second comer. The key requirement is first to use in commerce, and the test for infringement is whether there is a likelihood of confusion between two marks. If the originator establishes his or her field of commerce, then the law will prevent anyone from infringing directly or in a way that creates a likelihood of confusion as to source.

As the owner of an exclusive right, a shrewd trademark owner can foreclose competitors from exploiting a word or phrase and thus gain a competitive advantage. When launching new product lines, popular trademarks can also bring enormous market presence and value to something new, even if the product or service is untested. Sometimes, the best laid plans and trademarks can disappoint if the new product itself does not measure up.

In the late 1980s, the national newspaper USA Today used its reputation for colorful newspaper pages, encapsulated news features, and its market familiarity to launch USA Today—The Television Show. A newly conceived first-run program, the show was to be produced by Grant Tinker, a television producer of great renown. Tinker, husband of Mary Tyler Moore, had produced a string of hit television series, including The Mary Tyler Moore Show. The combination of USA Today and Tinker proved to be a dynamic team. The program was offered to television affiliates without so much as a pilot. What could go wrong with such firepower? Over 170 stations signed on to carry the show in prime TV time. Syndication deals to carry the show made big news.

Despite the success in establishing affiliations and garnering choice air time, which are normally the toughest things for a new program to achieve, the show itself failed to meet its own hype. After critics panned its “too fast-paced” programming and audiences stayed away, USA Today tried to remake its image. Grant Tinker was replaced by another producing wunderkind, Steve Friedman, fresh from success at NBC. Still, the program never quite developed a formula for television. Ironically, had the program been able to develop with less hype and more experimentation, say, if one or two pilots had been utilized to test the approach with the viewers, the advantage afforded by the extension of the USA Today brand might have paid off in a big way. As it turned out, the advantage earned by the trademark franchise was squandered. Had the show reached its potential, it would have been a powerful demonstration of the persuasive brand extension of trademarks. As matters played out, it illustrated the risks of associating a valuable trademark with an underachieving product.

A similar fate befell Coca-Cola when it launched its highly promoted drink New Coke, only to discover the public loved the old Classic Coke taste. Nevertheless, successful trademarks will always inspire a spin-off. The launch of MSNBC, the cable channel merging Microsoft and NBC, underscores the never-ending search for the effective brand extension. In sum, the proper handling of trademarks from their inception can provide lasting benefit to the owner.

Another important thing to know about copyrights and trademarks is that many important copyrights can be protected as trademarks as well. Cartoon characters, such as Mickey Mouse, fit this mold. Originally conceived as a drawing (that is, a copyrighted work), this friendly rodent has become one of the symbols of the Disney empire. Decades hence, long after the copyrights in the original films are in the public domain, Disney will prevent third party misuse of its works by trademark protection. Even though the original animated works will be freely available for recirculation by anyone in the public, no one will be able to commercialize the Mickey character alone without Disney's approval. And the same can be said for Minnie, Donald Duck, Daisy, Goofy, Snow White, and all the animated folks. While the storylines may be free to be developed, the names, animation, appearance, even voices, of the Disney characters will be independently protected as trademarks of the company.

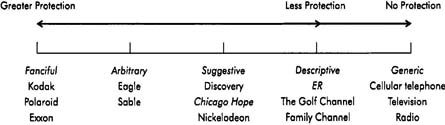

Trademark Continuum: Fanciful, Arbitrary, Suggestive, Descriptive, and Generic

Think of trademarks existing on a continuum or a ruler, as in Figure 10-1. At one end, there are fanciful marks, terms that have no dictionary meaning. These are coined terms, like Kodak, Polaroid, and Exxon. They are invented, then invested with an image. Based on the success and breadth of the products and services, they become unique identifiers that are granted significant trademark recognition.

Continuing along the ruler, we find arbitrary marks, those that contain words or phrases that are commonplace but applied in an uncommon way. There is no dictionary connection of the word Eagle to potato chips or Sable to cars. However, the words themselves connote images that the commercial users decided to capitalize on. Choosing an arbitrary word and associating it with a new good or service usually requires substantial effort in marketing and image building. It entails creating word associations that never existed before or purposefully using words that have no logical connection with one's products or services; needless to say, this is not an easy task. When done successfully though, the identification

of fanciful and arbitrary marks with products or services establishes the most useful and long-lasting bonding of all trademarks.

Most people gravitate to familiar words or phrases; creative types therefore try to use familiar words in inventive ways, suggesting what their product or service is about. Sometimes they seek to exploit words or phrases that already have an association in the consumer's mind and thus create suggestive marks. Titles of cable channels and television shows fit this bill routinely: Nickelodeon, Discovery, and Friends are but a few examples of titles that function as media service marks because they are suggestive of their content.

Nickelodeon is a particularly clever illusionary mark because it conjures up associations with entertainment and children without explicitly saying “children's channel.” Discovery is similarly intriguing because it suggests programming fare that is about science and nature without expressly stating so. In trademark terms, these titles are invested with greater potential for protection against competitors or others who would try to trade on their reputation. For example, when a video store shelved children's videos in a section called the Discovery Zone, the cable network raised some flack. It argued that the use either implied an association with or endorsement from the Discovery Channel. The matter concluded when the video store ended the practice.

As a program title for a weekly drama set in a medical emergency room, the CBS series Chicago Hope did not tell you much about the show's content, other than that you might expect it to be set in the city of Chicago. By contrast, a prime time competitor's title, ER, leaves little doubt about its medical emergency theme. In trademark terms, ER is a descriptive mark for a TV series about a hospital emergency room. The distinguishing feature of a descriptive mark is that it specifically states the essential element of the product or the nature of the service. One way to characterize the key ingredient is as follows: If you know what the product or service is about without ever coming into direct contact with it, the mark is descriptive. When one hears The All News Channel or The Golf Channel in connection with cable services, it requires no mental gymnastics to understand what programs these channels will feature.

The phrase generic mark is really a misnomer, because a generic word or phrase identifies a category of goods or services, rather than a source. The terms television, radio, and cellular telephone are generic. They cannot function as trademarks because they are inherently incapable of helping a consumer distinguish one source from another. Sometimes, a fanciful mark becomes so successful in the marketplace that the public and competitors treat it as generic. It happened to aspirin and cellophane. That is death to a trademark. Concern about a fanciful mark turning generic is why Xerox, Inc., has worked so hard over the years to inform consumers that Xerox is a trademark for photocopy machines. As the ads say, one does not make a Xerox, one uses a Xerox photocopy machine or creates a Xerox photocopy.

A variant of concern may also affect Microsoft's ownership of the Windows trademark. In March 2002, a Seattle judge denied Microsoft Corporation's request for a preliminary injunction to prevent a little company called Lindows.com, Inc., from using that name for a Linux-based operating system. The court's initial order suggests it believes Windows may be generic. Although there is a strong likelihood such a ruling, if issued, would be overturned on appeal, the preliminary scuffle presents an interesting question as to whether the mighty Microsoft Windows trademark could possibly be considered generic.

The possibility of a mark becoming generic underscores the grammar of trademark law. When developing trademarks, think adjectives. Properly used, trademarks qualify a type of good or service and, in sentences, should serve to modify a noun. Often, the noun is elliptical, but that does not mean it does not exist. While Cheers, the title of the television show, is a suggestive mark for a program about a bar, it is also a thriving trademark enterprise. The word and logo are associated with T-shirts, mugs, calendars—you name it. Any kind of product can bear the trademark, but the proper placement of the mark is always as that little old adjective.

The Strength of a Mark

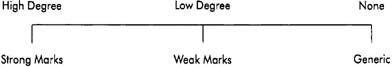

After the trademark continuum, another continuum should be mentioned, the “protection continuum.” This concerns the strength of a mark. Fundamentally, there are strong marks and weak marks (Figure 10-2). The stronger the mark, the more legal protection it is entitled to receive.

Marks gain strength in two ways: First, they are conceived with strength, because they are fanciful, arbitrary, or suggestive terms. The more a mark is removed from generic and descriptive terminology, the stronger it is. Second, a mark can be invested with strength by advertising and promotion. Even a weak,

descriptive mark can become so well known to the public and the identifier of a unique source that it is entitled to a high degree of trademark protection.

Cable News Network describes what it names quite simply. However, because it was the first cable news network, over 12,000 systems serving nearly 70 million subscribers carry it, and its prominent news-gathering success has made it a household name, Cable News Network and its acronym CNN are strong trademarks. Had several cable networks specializing in news been launched at the same time and had each tried to use the phrase that connects them most simply to the viewers, then Cable News Network might not be a strong trademark for anyone. The competitive use of phrases like The Game Channel, Game Network, and Game TV for new startup channels evidences the dilemma CNN would have had with direct competition in its early years.

Unique Identifiers in Specific Lines of Commerce

The most important feature of a trademark is that it stands for a unique source. Provided it does, the mark is protectable as a monopoly for its owner; if it does not, then it may not be a useful trademark at all. However, while trademark law grants a monopoly, allowing its owner to remove the mark from the commercial vernacular of competitors, it does so only with respect to the particular classes of goods and services actually associated with the mark. Because there are a finite number of words or phrases and consumers have certain expectations about the relationship between marks and services or goods, not all uses are restricted. Therefore, even though a new television series could not consider calling itself ER, no hospital in the country is prevented from using the label ER on account of the television series. Similarly, if a pharmaceutical firm produces an ER line of medicines, it will not be stopped from employing the phrase; there is little likelihood of public confusion about medicines and a television production.

Sometimes, even popular trademark owners carry their case too far. During the early years of the Reagan administration, a proposal to launch a network of “killer satellites” that could target and destroy enemy forces was proposed. The plan was dubbed Star Wars because of its futuristic, out-of-this-world theme. As press reports trumpeted the project, the owners of the popular Star Wars film trilogy took offense. A trademark dispute arose, in which the film company tried to shoot down the government's use of the phrase. The attack failed, a victim of the old “different class of services” defense.

A similar issue surfaced for the food maker Hormel, known throughout the world as the creators of Spam. Spam is a venerable trademark, and in the middle of the Internet craze Hormel discovered its carefully nurtured trademark became synonymous with one of the evils of e-mailing. Spamming is Internet-speak for sending unsolicited e-mail to millions of addresses. After much reflection and debate, Hormel developed a policy, now posted on its web page at www.hormel.com, in which the company accepts the unflattering nomenclature as a sign of the times, but urges all other uses of the trademark be true to its proper origins.

The misfiring of trademark phraseology can harm even presidential aspirations. During the 1996 presidential race, trying to echo former first lady Nancy Reagan's antidrug theme, “Just Say No,” Republican candidate Bob Dole exclaimed, “Just Don't Do It.” Unfortunately for Candidate Dole, a shoe company called Nike, known for the theme “Just Do It,” emerged to complain.

In sum, trademark law protects words or phrases, images, and trade dress, even designs and colors, in specific lines of commerce. When one moves into an unrelated field or endeavor, trademark legal protection may not follow. Thus, the word Eagle may be used for potato chips by one company, a car by a different company, a hand stapler by a third, and a TV production business by a fourth. Each can use the same trademark without violating another's trademark rights because consumers can readily distinguish the different sources of the marks. The strength of a mark is vital to this determination and so is the nature of the mark on the trademark continuum. If the NBC network challenged Newark Banking Company (NBC), it would lose. Even though it owns one of the most famous trademarks in the nation, the public's familiarity with acronyms is such that the marketplace can accept both titles. By contrast, a strong and fanciful mark like Kodak is in a much better position to prevent other uses even in unrelated areas. If it existed, Kodak Bank or Kodak Television Company would find the venerable film company on its back ASAP.

Likelihood of Confusion

These principles lead to the crucial legal test in trademark law: likelihood of confusion. The landmark case that explains this principle is Polaroid Corp. v. Polarad Electronics Corp., known as Polaroid for short. Since the law grants monopolies in trademarks and a limited number of words or phrases are available in the lexicon to describe goods and services, the Polaroid test looks at a variety of elements to determine if the two marks in question are likely to cause confusion as to source in the minds of a relevant consuming or purchasing public. If there is a likelihood of confusion, usually the first to have used the mark will prevail, and the second owner will either lose its rights to the mark or find its market severely restricted. If confusion is unlikely, the two marks can coexist.

The elements of likelihood of confusion, explained in the Polaroid decision, include

- The nature and strength of the marks. Are the marks fanciful, arbitrary, suggestive, descriptive, or generic?

- The similarity of the marks. How close are they in sight, sound, and meaning?

- The nature of the goods or services. Are they sold in the same channel of commerce?

- The gap to be bridged. Are the channels of commerce different, and, if so, how likely is it that the first user will bridge the gap?

- The sophistication of the buyers. Are they specialists, able to discern small differences in marks that can identify different sources?

- The intent of the second comer. Was the second user aware of the first, and is there any evidence of intentional copying?

- The evidence of actual confusion. Is there documented evidence that someone has been confused already?

- The quality of the defendant's product. Does it measure up to the original? Is there potential for negative publicity for the first?

Anytime the trademark of another is used, these issues must be considered. If a second comer cannot satisfactorily explain its use under each of these criteria, then its wisest course would be to choose another word or symbol. We take a closer look at this all-important issue in Chapter 13.

Secondary Meaning

Although a descriptive mark (such as 60 Minutes for a 1-hour television show) is usually deemed weak and unprotected, if the mark becomes well known to the public as originating from a sole source, it can gain status as a protectable trademark. When a mark achieves this status, it is said to have gained secondary meaning. In such cases, the word or phrase's secondary meaning points to a unique source.

Secondary meaning is secured through the expenditure of two precious commodities: time and money. The longer a mark is used by a sole source and the greater the public's awareness of the mark as originating from the source, the more likely it is that secondary meaning will attach. Therefore, a television program about cooking by European master chefs called, ingeniously, The Master Chefs, can gain secondary meaning by virtue of being the only such program so titled, by achieving solid ratings, and by having significant public exposure, through advertising and other publicity. In fact, many television programs readily fit this category: Touched by an Angel, The Tonight Show, Friends, Monday Night Football.

The issue of who is entitled to secondary meaning can spark debate. When David Letterman switched from NBC to CBS, the transfer was embittered with public wrangling. Among his television signature items, Letterman wanted to continue using his “Top 10” on CBS. NBC resisted, claiming the logo was theirs. The legal dispute was a small subplot in the larger issue of his departure, but CBS ultimately relented and came up with a close, albeit slightly different title, “The Late Show's Top 10 List.” Certainly “Top 10” is descriptive, but NBC claimed for television purposes it had achieved secondary meaning. No one else was doing it, and Dave had been using the phrase for the better part of a decade. The mark was identified with Letterman, because he created it during his employment by NBC, but the network used its status as his employer to claim ownership over his work. However, the addition of the phrase Late Show, which was CBS's alternative to Late Night, further separated the marks and gave Letterman's new network a viable trademark claim that the titles were distinguishable.

Ten years later, The “Top 10” dispute is something of a distant memory. However, a new battle may be brewing. One of the popular innovations of The Tonight Show is Jay Leno's reading and commenting on newspaper headlines and classified ads sent in by viewers. The routine has become so popular that David Letterman has taken to reading his own headliners. While no legal battle ensued, if The Tonight Show producers had taken the time and effort to invest the segment with strong trademarks, it might have formed the basis for a serious claim. As the matter now stands, it is symbolic of the common phrase, “imitation is the highest form of flattery.”

Use in Commerce and Intent to Use

A necessary characteristic of a trademark is that it be used. If a trademark is not used in commerce, no rights attach. Talking about a mark to friends does not create any trademark rights; sitting at a computer and composing a business plan does not create trademark rights. By contrast, marketing a product or telecommunicating a program creates rights. Prior to 1988, the use need only have been token; merely sending a mock-up of a magazine to a colleague in a different state was sufficient to support “use.”

However, since 1988, the use must be more than token, although that does not mean it must be very extensive. The change in 1988 came when Congress added the concept of intent to use into law. The new law states that as soon as one has an idea for a title or mark, one can file a request with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (PTO) and effectively reserve the mark. Once the application is approved, the mark can be held in reserve for up to 3 years, provided there remains a bona fide intent to actually carry out the plans to use the mark in commerce. That can be a valuable asset against a competitor. This generous opportunity altered the trademark landscape. Now, the race is on to file for a trademark.

Geographic Coverage of Marks

An important limitation on use of trademarks is geography. Unless the user of a trademark has applied to the PTO for federal registration of the mark or intention to use a mark, then the owner of the trademark is entitled to protection only in the geographic area where the mark has actually been used. Typically, trademark protection for nonregistered marks runs on a state-by-state basis. Thus, the same trademark can be owned by someone in Oregon and another person in Massachusetts. In broadcasting, this occurs frequently; for example, when a local radio station develops a format theme (Mix, Cool Jazz, or Hot Hits) and another station in a distant market picks up the same image. Unless protected by federal registration, the phrase can seep into many markets. Even though a station may be able to stop a local competitor, a broadcaster or business legally related to that local competitor but in a remote region may still be free to use it.

Concurrent Use

One balancing act of trademark law is the decision to let more than one party use the same mark. Concurrent use recognizes the fact that two local firms separated by geography or operating in different businesses can coexist as trademark owners. Their uses do not offend consumer sensibilities or business realities. Hence, one Sharper Image store can sell gadgets and another can cut hair. The original Holiday Inn can carve out a geographic zone in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, while the national franchise can operate everywhere else. Concurrent uses and even registrations on a split basis are essential to the fairness and balance of the trademark system.

These are the core principles of trademark law, but keep in mind that trademarks are regulated by a complex system of federal, state, and common laws. For example, a federal agency like the FCC assigns all sorts of identifiers, such as call signs and telephone numerators, which can have trademark significance. On top of this, there is a 50-state system of trade name registrations and, with the arrival of the Internet, a system of allocated domain names. We take a closer look at the trademark systems in the United States.