17

How to Manage Crises?

Far from wishing to resume talking about a set of specific skills, managing crises calls for a favorable capacity of the entire organization, both in space and over time, this chapter wraps up and discusses a number of fitting conditions from experience.

17.1. The fundamental principles of crisis management

Most economists assume that changes in financial markets are the result of chance or irrational behavior. Moreover, with the consequences that we know, in particular, at the stock exchange level. According to André Orléan [ORL 99] (and this hypothesis is in line with the case we have just studied concerning computer failures or failures in electronic circuits), the root causes of disturbances are only rarely independent. Indeed, they are always dynamic systems in which the actors or agents or disturbance factors interact. These interactions, as in neural networks, will be expressed with more or less force (called synaptic activity rate). For example:

- – on the stock market, speculative bubbles can exist without irrationality on the part of agents. They result from a general belief in the rise in future stock market prices and are combined with population movements. Similarly, when analyzing failures in large electronic systems, a similar procedure is used: (lower) belief coefficients are assigned to families of questionable components, which effectively increases the probability of failures due to these components to a much higher rate than that predicted by a normal statistical law. Conversely, a coefficient of greater belief would have the opposite result;

- – in regards to a given market, players do not always determine themselves according to their estimate of the fundamental value, as well as according to the expected evolution of prices. This unique forecast causes avalanche phenomena. In dynamic models, the aim here is to introduce positive feedback loops that simply reflect these amplification effects.

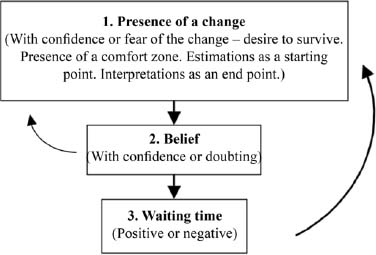

For these two reasons, we see that critical phenomena are more frequent than expected and are unpredictable insofar as they are specific to deterministic chaos models. The triangular system below (Figure 17.1) shows how important it is to distinguish the world from facts (estimates), perceptions (interpretations) and expectations (our often unconscious reaction to facts and perceptions).

Figure 17.1. Distinction between estimates and expectations in a crisis situation

Even if beliefs and expectations can seriously disrupt a system, we are not totally helpless because it is possible to act on two levels:

- – by announcing the appearance of a peak. According to the study by Robert Shiller of Yale University (where Benoît Mandelbrot was also a professor), we can construct a graph corresponding to the ratio of the price of American equities (Standard & Poor’s 500 index), divided by the average profits obtained over the previous 10 years. We thus obtain a standardized multi-fractal curve which has the interesting merit of announcing the appearance of a peak, i.e. a financial bubble. This graph corresponds to a possible correction of the markets and makes it possible to establish a method to anticipate somewhat the actions to be implemented;

- – by strategic positioning. In terms of risk management, you can make a profit, i.e. buying or selling shares at the right time. This opportune moment can be roughly anticipated with the graphical approach we have just described. Given what has been said about the rationality of financial market developments, we can to some extent predict the evolution of a group’s opinion and therefore position ourselves in terms of strategy: we do not act according to our own convictions or rationality, but according to the behavior of others. It is still a form of belief.

These changes in attitude are tactical rules that need to be developed on the ground.

17.2. Early warning risk signals and the basics of risk management

This section is largely taken from an article written by Ian Mittroff [MIT 01] in the field of the “art of risk management”. Mechanisms to detect early warning signs of crises enable companies to prepare for their eventuality. It is therefore necessary to implement tools based on the detection of low and relevant noise. Of course, we cannot know when and how a crisis occurs, but detecting an abnormal fact or situation early enough allows us to prepare for it and be on our guard. This provides the means and methods to better manage a crisis.

We examined the recovery plans available in the electronics and information systems industry. Such studies are very important because, nowadays, the economy depends largely on information systems and the management of our intangible assets. Any disaster can then have an impact on the company’s sustainability and the level of quality of the products and services it delivers. The effectiveness of recovery plans is dictated by three factors:

- – fear of losing assets in the event of a problem;

- – the societal impacts resulting from the disruption;

- – developing procedures and the ability to conduct disaster simulations for safety purposes.

Indeed, the purpose of risk management is threefold:

- – preventing disaster or disruption;

- – supporting the processing of the situation and setting up recovery plans;

- – (well, and this is less common) preventing relapse!

This provides a general framework that could be used to manage serious crises. Without understanding all the principles in order to use them to prepare for its eventuality, companies cannot develop the necessary capacities to survive a major crisis. Examples abound: ENRON, BOPHAL, PERRIER, etc. The framework developed here consists of four elements: crisis families, crisis mechanisms, crisis systems and stakeholders. All these elements must be understood before, during and after the crisis. In fact, this framework is a combination of best practices and forms a benchmark against which all companies can measure their crisis management capabilities.

17.2.1. Several families of crises

The purpose of this section is not to provide a text on risk management; many books, very academic, practical and comprehensive, already do this. It is simply a matter of providing a few reminders and emphasizing some important points as they open up new avenues towards a new paradigm in risk management.

Crises are always grouped into categories or families. While there are significant differences between all these families, there are also strong similarities between the crises within each family. For example, a distinction is made between natural (disasters), economic, physical, psychotic or information-related crises, reputation, leadership behavior and human resources.

Few companies consider and plan a sufficiently wide range of crises in several families. The majority of them (if they can be said to manage crises) are mainly preparing for natural and industrial disasters. This is due not only to the fact that data on such disasters are constantly recorded but also because they affect all companies in the same way. As a result, they appear less threatening to the collective consciousness of the company! In the case of earthquakes, the devastating effects can be reduced through better building regulations, as well as through the decentralization of database servers to safer locations. Since it is impossible to predict and prevent this type of disaster, the fact that an earthquake occurs generates less public criticism than other types of crisis. On the other hand, the reactions will be reversed if the company that is located in a sensitive area (near a city) starts discharging toxic effluents into the sewers. The same applies to all risks related to the sustainable environment.

In the field of risk and crisis management, a new fact related to the economic development of emerging countries should be highlighted. Until now, companies in poor countries have been considered second-rate companies capable of copying and producing consumer products designed and manufactured in the West and run by large Asian or South American families and dynasties. As a reminder, the development of emerging markets dates back to the 1980s, and we had the privilege of a study trip at IBM as early as 1979.

But these caricatures are completely outdated: the risk is more than real. On the past list of the world’s top 500 companies, more than 60 came from developing countries (Le Monde Informatique, no. 885; Newsweek, October 12, 2007). Some produced 80% of the toys sold in the world; others were leaders in electronics and IT (Samsung, Lenovo, etc.) and even in the food industry (Grupo Modelo with the Corona brand). France had experienced the MITAL case. We must keep in mind that China trained some of its best engineers in major American universities and that India produces a fair 1 million engineers each year. Companies in these countries are therefore based on “intelligence”: they are able to design highly sophisticated advanced industrial products, implement advanced line management (see Cemex, etc., in addition to low labor costs), produce according to the best in class specifications and quality standards, have access to advanced technologies (see Lenovo, Samsung, Renault, Hyundai, etc.) and meet sustainable environmental criteria, if necessary!

Is this a catastrophe? The answer is yes insofar as this economic upheaval is recent, rapid and propagative. The origin of this turbulence is not entirely due to chance: for political, strategic, technical (Internet) and societal reasons, it could not be avoided.

However, in terms of preventive measures and the nature of our economic models, we have all contributed to the development of the crisis: in France, for example, having shown financial indiscipline for more than 30 years, the deficit is significant; in the 2000s, the West indiscriminately invested in certain so-called high-tech companies and experienced the 2000–2002 bubble; over-indebtedness, over-consumption, over-protection with, as a consequence, non-investment in the sectors of the future, thus accentuating the crisis. Meanwhile, some emerging countries are functioning like the grandmother of yesteryear: they are saving, building structures and infrastructure, working, etc. They are finally helping the rest of us because they are supporting economic growth through double-digit growth in their demands and needs.

Since each action is always followed by a reaction, this evolution still has a counterpart: CO2 emissions are increasing and energy demand is increasing. But it does not matter: we can think that in a very short time, whether we help them or not, their standard of living will have joined ours and that we will be able to share the same living conditions and environmental constraints. Isn’t this another way to manage a crisis?

17.2.2. Mechanisms and crisis preparation

After having described some crisis phenomena, it is useful to investigate their mechanisms with their associated phenomena. When a company goes beyond natural disaster planning, it usually focuses on “major crises” internally or in the sector. In the chemical and electronics industries, companies are preparing for unintentional spills of toxic products and fires because these risks are part of their daily lives. This last point is particularly true in factories where high value-added products are developed.

On the other hand, and as described above, companies must be constantly encouraged to prepare for crises that go beyond their immediate world: IT cannot do without electronics and electricity. Interactions are all the stronger as we are still moving towards the integration of transdisciplinary technologies. It is also necessary to be vigilant on a few points: a specialist in electronics or automation will always be able to convert or evolve towards IT; the opposite is not true. A good sales representative can become a good marketer; the opposite is not necessarily true, etc.

Studies on crisis management show that, with a few exceptions, all types of crises can occur in all sectors of activity and in all companies, regardless of their sector of activity. The only thing we cannot predict is the exact form the crisis will take and when it will occur.

Let us take an example from the article by I. Mitroff to illustrate this fact [MIT 01]. In 1990, Larousse, the world’s largest publisher of French-language dictionaries, had to recall 180,000 volumes of its Petit Larousse en couleurs because of a legend under the photo of two mushrooms: it described the deadly mushroom as harmless and vice versa! No one could know whether it was a simple human error or a bad intention. In any event, since the error could cause serious damage to mushroom consumers, it was already a crisis no less serious for this publisher, especially since it was unpredictable and Larousse therefore had no pre-established plan to manage it.

Such examples abound: in the automotive industry, vehicle recalls for technical reasons are frequent; some have been organized to correct minor safety problems, but relayed by poor communication; they have not achieved the expected commercial effects. In any type of crisis, whatever the type, another type of crisis can be triggered and, in turn, result from it. In other words, a crisis can be both the cause and the effect. Again, this is due to the interactions that exist in our complex systems, and this shows how difficult it is to be preventive and effective. Here again, we come across the problems of unpredictability of our models.

The organizations best prepared for crises are those that have a plan for each crisis category. Why? The best-prepared companies do not study crises in isolation, but try to consider each one in conjunction with all the others in a global system. Paradoxically, they do not care about the details of crisis management plans. They focus mainly on developing their capacity to implement the plans. What would be the point of having the best plan in the world if we were unable to execute it? Or if it was not applicable to the unexpected arrival of the next crisis. What matters most, in anticipation of such situations, is to develop the right reflexes and implement the conditions that allow us to be reactive. As mentioned above, what is important is to have procedures (not gas plants!) to manage simple cases, and then to conduct real exercises or simulations to increase our ability to react through learning.

From this point of view, we proceeded in the same way as when, at the IBM Development Laboratory in La Gaude, we developed test techniques on automatic switches that only measured the ability of equipment to recover from a disturbance or turbulence to which it was subjected. Given the properties associated with this type of complex system and the state of our knowledge in the field of risk management, there is not always the right solution.

Studies show that there are a small number of extremely important mechanisms to respond to a crisis before, during and after it occurs. The fact that they are involved at all stages is sufficient to prove that managing a crisis is not just about reacting after the fact. Crisis management can only be effective if it shows initiative. The best way to manage a crisis is to prepare for it beforehand. After that, it is already too late. These mechanisms enable companies to anticipate and foresee disasters, respond to them, contain them, learn from them and develop new effective organizational procedures. Man-made crises can be identified by a variety of warning signs, long before they occur. When we can intercept them and act upstream, we can avoid problems.

17.2.3. Detecting early warning signals and containing damage

It is therefore necessary to put in place mechanisms to detect signals before the imminence of the crisis prevents them from functioning. For example, increased absenteeism or graffiti on factory walls reflect social unrest and latent violence in the workplace; a sharp increase in the rate of workplace accidents is often a sign of an impending industrial explosion. Moreover, if these signals are not identified, the company not only reinforces the possibility of the crisis but also reduces its chances of controlling it.

However, even the best signal detection mechanisms cannot prevent all crises. Therefore, one of the most important aspects of crisis management is to contain damage to prevent undesirable effects from spreading and reaching parts of the company that are still intact.

Two mechanisms are very revealing of why the majority of crisis management programs are ineffective: lessons learned from past crises and the revision of systems and mechanisms to improve their management in the future. Indeed, few companies perform an autopsy of the crises they have suffered or narrowly avoided and, when they do, they do not conduct it properly and do not draw the necessary lessons from it. These autopsies must be an integral part of a crisis audit covering the company’s strengths and weaknesses in relation to the four factors described.

17.3. Five fundamental elements that describe a company

Five fundamental elements make it possible to understand a company, however complex it may be, and its strategic issues:

- 1) technology (information systems);

- 2) the organization (structures);

- 3) entrepreneurship and human factors;

- 4) culture (including organizational memory) and skills;

- 5) the profile and psychology of the leaders.

These factors are not independent of each other. They are closely intertwined and play complementary or contradictory roles. For example:

- – modern companies, whatever the sectors of activity considered, operate using a wide range of sophisticated technologies, from computers processing information to the units and processes manufacturing the products. However, the technology is managed by human beings, subject to error. Whether we admit it or not, humans are subject to fatigue, stress and irritability, for example. These are all factors that lead to intentional or unintentional errors. Similarly, the organization is a key performance factor in the sense that it makes it possible to set up an effective and efficient communication system between the various partners. When the information system fails, we will have to change the organization, as well as the profiles of the staff’s skills. If human errors are frequent, we may have to review the tools and means of production, as well as invest in information systems, etc.;

- – in terms of human factors, the objective is to precisely assess the causes of human errors and to look for systems that reduce or even eliminate the effects of these errors. Let us take the cockpit of an aircraft: for the laypeople, the controls are surprising and placed in such a way that an amateur would be unable to understand them and even more unable to use them. But engineers studying human factors have analyzed the piloting process and the location of the aircraft’s controls and arranged them in such a way as to minimize the risk of catastrophic error on the part of pilots who often work under stressful conditions. In addition, training hours are also required to set up appropriate reflexes and to ensure that nothing is left to chance in the operation of the aircraft. These considerations are just as important, if not more so, in chemical or nuclear plants, not to mention operating rooms;

- – technology also leads to different types of errors when integrated into a complex organization, first because communications must move through many levels and second because reward systems promote certain types of behavior and try to eliminate others. These are all factors that make it possible for information to reach the right person in time to make the right decisions! Among the induced effects of the computer tools used by specialists in particular, it is necessary to mention an important negative effect: that of the rise of corporatism. This constitutes a significant risk of disorganization and acculturation within the company. Indeed, the person involved in the network will first exchange information with network partners, share experiences and obtain appropriate information to solve problems for which he or she is responsible in the company, in short to flourish. He or she belongs first to the network before sharing the excitements of the company. In the event of a change of assignment or reorientation of his or her professional career, it is through the network, and also by the network, that he or she will be able to benefit from opportunities for reclassification. This phenomenon has a direct impact on the development of skills in the company and on its organization.

17.4. About stakeholders

The main factors determining the success of crisis management are corporate culture and the psychology of the managers. The team that will operate best will be the one that does not hide its face, has the greatest cohesion (compactness) and does not fall into grandiloquence. On the other hand, a poorly functioning team will not only fail to effectively manage the crisis but will also provoke it and intensify its most dangerous parameters, thus extending its duration.

One of the first and most important results revealed by crisis management studies is that companies, like human beings, use Freudian defense mechanisms to deny their vulnerability in major crises. Such mechanisms explain the low levels of investment in the resources and planning required to manage these crises. Moreover, a crisis cannot be properly managed without the presence of all internal and external organizations, institutions and individuals, who must cooperate with leaders, implement preparation or training programs and share plans. These stakeholders may include staff, police, the Red Cross, firefighters and any other entities that may be called upon to assist. If a company wants to have the capacity to manage a crisis, it must maintain close relationships with key stakeholders.

The best crisis management solution is the one that combines total quality management, environmental protection and other forms of risk management. Crisis management is doomed to fail if it is considered as a separate and independent additional program. It must be an integral part of the business and must be systematically designed and implemented, otherwise it will become part of the problem and not part of the solution.

This nevertheless leads us to clarify a point concerning the standard profile of managers of companies subject to the eventualities of risk. This profile is directly linked to the training and skills acquired, for example, in business and management schools.

A case in point: as part of its activities, our company I2D (Institut de l’innovation et du développement) was once looking for a commercial agent. It approached two business schools and found only marketing specialists demanding a permanent contract, a fixed salary and a car. After investigation, it turned out that the students in these schools were trained for careers in finance, management and consulting. This anecdote shows a certain gap between the training of some schools and the needs of the professional environment. As stated in this book, the objective of traditional training is always to create maximum value, optimize the company’s margin, ensure maximum dividend payment and obtain good remuneration. Such specialists are certainly not, at the cultural level, entrepreneurs or leaders capable of setting out a vision and strategy for the development of business and employment wealth. What ability do they have to understand risks and manage crises… in a company with social objectives and choices? Giving advice, making the weather nice in a company without being involved, is certainly safer than fighting to implement a strategy. All this poses a problem of matching skills and motivation.