Now more than ever, organizations are increasingly becoming acquirers[1] of needed capabilities by obtaining products and services from suppliers and developing fewer of these capabilities in-house. The intent of this widely adopted business strategy is to improve an organization’s operational efficiencies by leveraging suppliers’ capabilities to deliver quality solutions rapidly, at a lower cost, and with the most appropriate technology.

[1] In CMMI-ACQ, the terms project and acquirer refer to the acquisition project; the term organization refers to the acquisition organization.

Authors’ Note

It has been challenging to name the CMMI for Acquisition (CMMI-ACQ) model and this book. The reason is that the activities covered in these documents are called different things in different industries, organizations, and even countries. Instructors who teach CMMI-ACQ ask their students to tell the class what these activities are called in their organizations. At last count, more than 20 different terms were used to refer to what we call “acquisition.” Our choice to use “acquisition” is consistent with the term used to describe these activities in ISO 15288.

Acquisition of needed capabilities is challenging because acquirers must take overall accountability for satisfying the user of the needed capability while allowing the supplier to perform the tasks necessary to develop and provide the solution.

According to recent studies, 20 percent to 25 percent of large information technology (IT) acquisition projects fail within two years and 50 percent fail within five years. Mismanagement, an inability to articulate customer needs, poor requirements definition, inadequate supplier selection and contracting processes, insufficient technology selection procedures, and uncontrolled requirements changes are factors that contribute to project failure. Responsibility is shared by both the supplier and the acquirer. The majority of project failures could be avoided if the acquirer learned how to properly prepare for, engage with, and manage suppliers.

Authors’ Note

A March 2008 report from the Government Accountability Office (GAO) found that 95 programs in the 2007 portfolio of major defense acquisition programs exceeded original estimates by $295 million, with deliveries almost two years late, on average. Total acquisition costs for these 95 programs had risen 26 percent, compared with 6 percent in 2000. Sixty-three percent had changed requirements after starting development, and about half of the programs experienced at least a 25 percent increase in expected lines of software code [GAO: Defense Acquisition, 2008].

In addition to these challenges, an overall key to a successful acquirer–supplier relationship is communication.

Authors’ Note

General Motors Information Technology is a leader in working with its suppliers. See the case study in Chapter 7 to learn more about how sophisticated the relationships and communication can be with suppliers.

Unfortunately, many organizations have not invested in the capabilities necessary to effectively manage projects in an acquisition environment. Too often acquirers disengage from the project once the supplier is hired. Too late they discover that the project is not on schedule, deadlines will not be met, the technology selected is not viable, and the project has failed.

The acquirer has a focused set of major objectives. These objectives include the requirement to maintain a relationship with the final users of the capability to fully comprehend their needs. The acquirer owns the project, executes overall project management, and is accountable for delivering the needed capabilities to the users. Thus, these acquirer responsibilities may extend beyond ensuring that the right capability is delivered by chosen suppliers to include such activities as integrating the overall product or service, transitioning it into operation, and obtaining insight into its appropriateness and adequacy to continue to meet customer needs.

CMMI for Acquisition (CMMI-ACQ) provides an opportunity to avoid or eliminate barriers in the acquisition process through practices and terminology that transcend the interests of individual departments or groups.

Authors’ Note

If the acquirer and its suppliers are both using CMMI, they have a common language they can use to enhance the relationship even further.

This document provides guidance to help the acquirer apply CMMI best practices.

CMMI-ACQ contains 22 process areas. Of those, 16 are CMMI Model Foundation (CMF) process areas that cover process management, project management, and support. We will discuss CMF in more detail later in this chapter.

Authors’ Note

The CMF concept is what enables CMMI to be integrated for both supplier and acquirer use. The shared content across models for different domains enables organizations in different domains (e.g., acquirers and suppliers) to work together more effectively. It also enables large organizations to use multiple CMMI models without a huge investment in learning new terminology, concepts, and procedures.

Six process areas focus on practices specific to acquisition addressing agreement management, acquisition requirements development, acquisition technical management, acquisition validation, acquisition verification, and solicitation and supplier agreement development.

All CMMI-ACQ model practices focus on the activities of the acquirer. Those activities include supplier sourcing, supplier agreement development and award, and management of the acquisition of capabilities, including the acquisition of both products and services. Supplier activities are not addressed in this document. Suppliers and acquirers who also develop products and services should consider using the CMMI for Development (CMMI-DEV) model.

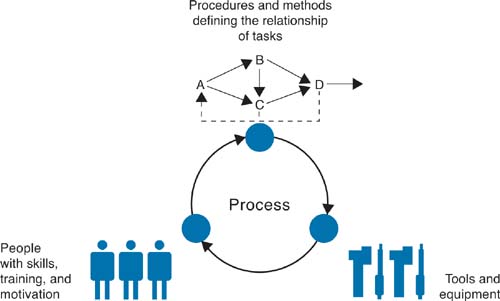

In its research to help organizations develop and maintain quality products and services, the Software Engineering Institute (SEI) has identified several dimensions that an organization can focus on to improve its business. Figure 1.1 illustrates the three critical dimensions on which organizations typically focus: people, procedures and methods, and tools and equipment.

But what holds everything together? It is the processes used in your organization. Processes allow you to align the way you do business. They allow you to address scalability and provide a way to incorporate knowledge of how to do things better. Processes allow you to leverage your resources and to examine business trends.

Authors’ Note

Another advantage of using CMMI models for improvement is that they are extremely flexible. CMMI doesn’t dictate what processes to use, what tools to buy, or who should perform particular processes. CMMI provides a framework of flexible best practices that can be applied to meet the organization’s business objectives, no matter what they are.

This is not to say that people and technology are not important. We are living in a world where technology is changing by an order of magnitude every ten years. Similarly, people typically work for many companies throughout their careers. We live in a dynamic world. A focus on process provides the infrastructure and stability necessary to deal with an ever-changing world and to maximize the productivity of people and the use of technology to be more competitive.

Manufacturing has long recognized the importance of process effectiveness and efficiency. Today, many organizations in manufacturing and service industries recognize the importance of quality processes. Process helps an organization’s work force meet business objectives by helping them work smarter, not harder, and with improved consistency. Effective processes also provide a vehicle for introducing and using new technology in a way that best meets the organization’s business objectives.

In the 1930s, Walter Shewhart began work in process improvement with his principles of statistical quality control [Shewhart 1931]. These principles were refined by W. Edwards Deming [Deming 1986], Phillip Crosby [Crosby 1979], and Joseph Juran [Juran 1988]. Watts Humphrey, Ron Radice, and others extended these principles even further and began to apply them to software in their work at IBM and the SEI [Humphrey 1989]. Humphrey’s book, Managing the Software Process, provides a description of the basic principles and concepts on which many of the Capability Maturity Models (CMMs) are based.

The SEI has taken the process management premise, “the quality of a system or product is highly influenced by the quality of the process used to develop and maintain it,” and defined CMMs that embody this premise. The belief in this premise is seen worldwide in quality movements, as evidenced by the International Organization for Standardization/International Electrotechnical Commission (ISO/IEC) body of standards.

CMMs focus on improving processes in an organization. They contain the essential elements of effective processes for one or more disciplines and describe an evolutionary improvement path from ad hoc, immature processes to disciplined, mature processes with improved quality and effectiveness.

The SEI created the first CMM designed for software organizations and published it in a book, Capability Maturity Model: Guidelines for Improving the Software Process [SEI 1995].

Today, CMMI is an application of the principles introduced almost a century ago to this never-ending cycle of process improvement. The value of this process improvement approach has been confirmed over time. Organizations have experienced increased productivity and quality, improved cycle time, and more accurate and predictable schedules and budgets [Gibson 2006].

Figure 1.2 illustrates the models that were integrated into CMMI-DEV and CMMI-ACQ. Developing a set of integrated models involved more than simply combining existing model materials. Using processes that promote consensus, the CMMI Product Team built a framework that accommodates multiple constellations.

The CMMI Framework Architecture provides the structure needed to produce CMMI models, training, and appraisal components. To allow the use of multiple models within the CMMI Framework, model components are classified as either common to all CMMI models or applicable to a specific model. The common material is called the CMMI Model Foundation, or CMF.

The components of the CMF are required to be a part of every model generated from the framework. Those components are combined with material applicable to an area of interest to produce a model. Some of this material is shared among areas of interest, and other portions are unique to only one area of interest.

A constellation is defined as a collection of components that are used to construct models, training materials, and appraisal materials in an area of interest (e.g., acquisition and development). The Acquisition constellation’s model is called CMMI for Acquisition, or CMMI-ACQ.

The CMMI Steering Group initially approved an introductory collection of acquisition best practices called the Acquisition Module (CMMI-AM), which was based on the CMMI Framework. Although it sought to capture best practices, it was not intended to become an appraisable model or a suitable model for process improvement purposes.

Authors’ Note

The Acquisition Module was updated after CMMI-ACQ was released. Now called the “CMMI for Acquisition Primer, Version 1.2,” it continues to be an introduction to CMMI-based improvement for acquisition organizations. The primer is an SEI report (CMU/SEI-2008-TR-010) that you can find at www.sei.cmu.edu/publications/.

General Motors partnered with the SEI to create the initial draft Acquisition model that was the basis for this model. This model represents the work of many organizations and individuals.

Acquirers should use professional judgment and common sense to interpret this model for their organizations. That is, although the process areas described in this model depict behaviors that are considered best practice for most acquirers, all process areas and practices should be interpreted using an in-depth knowledge of CMMI-ACQ, organizational constraints, and the business environment.

Authors’ Note

Every CMMI model must be used within the framework of the organization’s business objectives. An organization’s processes should not be restructured to match a CMMI model’s structure.

This document is a reference model that covers the acquisition of needed capabilities. Capabilities are acquired in many industries, including aerospace, banking, computer hardware, software, defense, automobile manufacturing, and telecommunications. All of these industries can use CMMI-ACQ.