WHEN IT COMES to tax-advantaged investments, it's hard to beat municipal bonds, or munis, as they're popularly called. The American public, particularly those in income tax brackets over 25 percent, has been quick to capitalize on these investments, so much so that the municipal bond sector is the only bond category in which individuals, as opposed to institutions, exert a significant force. However, their strength has been diluted by the activities of hedge funds and arbitrage accounts that have been attracted to the market by the comparatively steep yield curve.[49] It's interesting to note that European institutional investors now see the value of U.S. municipal bonds and are vigorous participants in this $2.1 trillion market.[50] In 2006, munis outperformed taxable bonds. "Not only were the absolute returns strong, but on a risk-adjusted and tax-adjusted basis, they are compelling,"[51] says Paul Disdier, director of municipal securities at Dreyfus.

Despite their popularity and significant tax advantages, municipal bonds remain a mystery to most people. In large part, this is because munis encompass such a broad universe of bonds of varying quality and returns. In other words, if you've seen one muni, you haven't seen them all.

Our goal in this chapter is to render any seemingly mysterious features both intelligible and manageable for investors. We have been buying and selling many millions of dollars worth of munis for our own personal needs and for our clients for the past twenty-five years, and in the process we've made a lot of money for both our bank accounts and theirs. We hope the information in this chapter will help you do the same.

We'll begin with some basics.

Issuers. A key feature to understand about munis is that they are issued by states, local governments, or special public entities, such as school districts and sewer authorities. In large part, the creditworthiness and revenue sources of these various issuers determine the financial attractiveness of their bonds.

Taxes. Tax free is a relative term when applied to munis. Although most munis are exempt from federal income taxes, some are taxable and some are subject to the alternative minimum tax. Many munis find it impossible to escape the clutches of state or city tax departments. Fortunately, the Bond Market Association has taken a giant step in clarifying this situation by creating the Web site

www.investinginbonds.com, which provides helpful information to compare a tax-free yield to the taxable yield. For example, this site can help you determine if a 4.5 percent muni or a 6.5 percent corporate yield is more attractive in tax terms. Later in this chapter you will find a simple formula you can use to help make the comparison yourself. However, the tax law is so complicated that you should seek definitive advice on the precise value of municipal bonds in your particular situation from your personal adviser.Redemption dates. Munis are generally issued in serial form. This practice protects the issuer from paying out a huge lump sum. For example, when issuing $10 million worth of construction bonds, a school district will sell them all at once but have blocks with different redemption dates. In this case, you could buy two blocks of bonds from the same issue, yet each would be redeemed at a different time. This allows you to target the bonds to mature at a time that suits your needs.

Interest. Municipal bonds pay interest either semiannually or only when the bond matures. The issuer, in conjunction with the underwriters, decides whether the bonds are issued as paying current interest or as capital-appreciation zero-coupon bonds. If the bonds pay current interest, they can be issued at a discount, at a premium, or at face value.

Pricing. Municipal bond pricing is a bit like what goes on in an "Asian bazaar." Although muni bonds all start with a minimum $5,000 face value and are quoted in decimals, market forces quickly take over and raise or lower the purchase price. These prices are no longer difficult to track because muni trades are reported, with a fifteen-minute delay, at

www.investinginbonds.com.Call features. Here's a big catch: Some municipal bonds have fixed call options, with a first call usually between five and ten years from their date of issue, after which they're callable with a thirty-day notice. Others are noncallable for their entire lives. Some have a sinking fund. Some revenue bonds have extraordinary calls that are only exercised in specified catastrophic situations. Housing bonds generally can be called at any time due to mortgage prepayment. Any call exposes you to reinvestment risk.

Form. Most issues are in book-entry form, and a brokerage house or other custodian must hold them. Some appear as registered bonds with certificates you can hold in your hands.

We find municipal bonds are not only profitable but also a comparatively low-risk investment. Periodically, the rating agencies issue statements reevaluating the health of various market sectors. Since rated municipal bonds are extremely stable, these reevaluations do not have much impact for the buy-and-hold investor. Fitch Ratings examined data from 1979 to 1999 and found that the overall default rate was less than 1.5 percent on its sample. In a 2003 update of default risks, Fitch's analysts said that the additional data revealed "no meaningful changes" overall. One exception is the higher default rate for environmental facilities as a result of the deregulation of that sector, which had been expected.[52] The ten-year cumulative default rate from 1970 to 2005 for Moody's investment-grade municipals, excluding the safest sectors of general obligation and water and sewer bonds is .2883 percent.[53] Moody's points out that the default rate is so low because municipalities receive extraordinary assistance from federal and state governments, as exhibited in the bailout of Gulf Coast communities in the wake of Hurricane Katrina in 2006. In addition, Moody's notes that the government instituted reforms—such as oversight of troubled municipalities, the implementation of generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), and tighter controls on investment funds—in response to default risk. No reforms have yet dealt with increasing defaults in health care or affordable housing.[54]

The spectrum of risk for municipal bonds is wide. Some categories are extremely safe: that group includes general obligation bonds, because they require voter approval, and revenue bonds, which have substantial and multiple sources of funds. You can be comfortable buying these categories if they have an A rating or better or if one of the major muni bond insurance companies insures them.

Some munis, however, are extremely risky, with narrow streams of revenue that may not be secure. These bonds will have a low rating or none at all. A nonrated bank may guarantee them. Through the media, you'll learn about problems in an industry, although they may not mention bonds being at risk specifically. For example, note the regular drumbeat of articles on the problems of hospital reimbursements and tobacco settlements. Such "big picture" information tells you that those market sectors represent a weaker area in the muni market. Tread cautiously. In good times, lower-grade bonds may yield only slightly more than better quality paper—maybe 15 or 20 basis points—but the spreads open up in bad times. That means that buyers lower the price they're willing to pay when there is negative economic news, whereas sellers maintain the price at which they're willing to sell.

Municipal bonds are subject not only to specific risks particular to certain classes of bonds but also to risks that all muni bonds have in common. Risks common to all munis include the following:

Fluctuations in state and federal aid. Fluctuations in aid have destabilizing effects on municipal budgets and can impair their ability to repay fixed debt. Federal programs often provide only start-up costs or a portion of capital costs. Relying on the traditional last-minute state appropriation to fund its ailing schools and city, Buffalo, for example, was devastated to find the state's cupboard empty at the close of 2001 because money had been diverted to disaster activities as a result of the September 11 attacks. Having already spent the $54 million they were seeking, the city and school district had to drastically cut services to cover the shortfall.[55]

The devastation caused by Hurricane Katrina to New Orleans and surrounding areas, however, did not cause a blip in the municipal credit world because not a single issuer missed interest or principal payment on debt sold by local governments. The federal and state governments stepped in to provide much needed liquidity to the badly damaged area.

Lack of diversified tax base. Dependence on a restricted revenue source increases the vulnerability of both general obligation (GO) and revenue bonds. Airline terminals, for example, saw their revenue decline after the September 11 attacks, and as a result, many of the bonds backed by this revenue were downgraded.[56] What's more, bonds issued for limited geographic areas, like specified assessment districts, such as the Los Osos, CA, Community Services District Wastewater Assessment District No.1, can default when politics and mismanagement impede the completion of a project.[57]

Fiscal imprudence. Putting political decisions before fiscal responsibility has frequently resulted in rating downgrades or worse. The news in 2006 was that municipalities' pension funds were only 84 percent funded on average, but those deficits were dwarfed by the roughly $700 billion and $1 trillion in unfunded health care and other postemployee benefits that had previously been paid on a pay-as-you-go basis. For the first time, new 2006 Government Accounting Standards Board requirements for pension funds were implemented, requiring municipalities to report both the accrued liabilities and their annual costs for items such as health care.[58] Unfunded pension obligations have burgeoned as our feel-good politicians try to defer the pension fund reckoning until after they've left office. Unions make demands and cities and states cave into the requests, figuring that they can pay salary increases now and defer contributions to the pension plans. In 2006, the San Diego pension fund fiasco resulted in indictments of the mayor and five former pension officials, and that sad story has been repeated in some form nationwide. Pension funds have begun issuing bonds and investing the money in stock in the hope that a rising stock market would bail them out. As of 2006, this strategy was not working. Whether we pay now or pay later, the only source of revenue is the taxpayer.

Excessive debt. Debt mountains soaring over the tax base or revenue source is not a good sign. Indications of possible problems include increases in the amount of debt, the requirement of paying off sizable issues in one year, and increases in the amount of annual interest. New York City is a case in point. Following the September 11 attack, the city was put on credit watch after its revenues from taxes throughout the city plunged while its need for money for rebuilding and essential services skyrocketed.

Ratings are a key guide to understanding the creditworthiness of bonds. Ratings enable the most inexperienced to purchase bonds; such investors rely on ratings to protect them from loss. Although the rating companies do not want investors to base their purchase solely on the judgment reflected in the ratings, they are, nevertheless, a very important consideration in the decision-making process. During the period of 1986 to 2006, for example, Standard & Poor's found the AAA-grade bonds quite stable even if they lack enhancements, with 96 percent remaining the same one year later. For bonds rated BBB or lower, the likelihood of their remaining stable one year later was 88 percent.[59]

All of Standard & Poor's default studies, the present update included, have found a clear correlation between credit quality and default remoteness: the higher the rating the lower the historical average of default, and vice versa. Over each time span, lower ratings correspond to higher default rates.[60]

The investment attractiveness of munis is frequently gussied up with the addition of insurance. An insured bond, which means the face value and interest payments are guaranteed, is given a higher rating than one that is not insured. This extra coverage that guarantees payment makes munis especially attractive. Sometimes only specific maturities of a bond issue are insured. Insurance, however, costs money, and issuers often seek to do without it if they can obtain an AA rating or better on their own. For example, in December 1994, the Wissahickon School District in Pennsylvania issued $5 million of bonds. The district received an AA rating that made it possible to save the $60,000 that would have been required to purchase bond insurance had it received a lower rating.

However, insurance can be very comforting when disaster strikes. After Hurricane Katrina, investors feared that bonds would default and the insurers would fail to meet their obligations. According to Chip Peebles, a senior vice president at Morgan Keegan & Co. in Memphis, "Bond insurance has proven its worth through this whole thing. It's what we've been telling our customers: if you're insured, rest easy. They are going to pay."[61]

The insurance firms are rated, and their ratings are automatically transferred to the bonds they insure. Thus, a firm receiving an AAA designation from a major rating agency bestows that designation on all the bonds it insures. The firms do not insure bonds willy-nilly. They carefully scrutinize the creditworthiness of each and insure only those they deem likely not to default. These are private and public companies with no government backing—no relation to FDIC, which insures your bank deposits (see Figure 10.1). Naturally, the insurance does not cover any premium over face value that you pay for a bond.

Sophisticated buyers always ask what the rating on an insured bond would be without any insurance. It is better to have insured bonds that are of better credit quality than insured weaker credits. If the underlying rating is strong, you can rely on the underlying strength of the bond as well as on the insurance for protection. This is called belt-and-suspenders protection.

This is as good a place as any to note that insurance guarantees return of interest and principal, but it does not necessarily protect against a falling price for trading purposes—market risk. When Wall Street heard that a nonprofit bond issuer for student apartment complexes was withdrawing money from operating expenses to build up its reserve fund, the rumor mill cranked into high gear on the fear there might be a technical default. The price of the actively traded bonds plummeted 8 percent in a day.[62]

Because these were insured bonds, if there had been a default, the bond insurers would have continued to pay interest and principal when due. Despite this assurance, if you sold the bonds in the bad news market, you would have suffered a loss. For example, after Hurricane Katrina, even some insured bonds sold for 50 basis points more than those outside the region.[63] As they say in the marketplace, there's a moral to the story: Insurance does not make a bad bond good, but it's surely much better than not having it at all. It helps you sleep at night.

Some bonds offered in the secondary market are enhanced after issuance. They are either escrowed or prerefunded. Municipalities generally add these features as an approved accounting method for reducing the debt on their balance sheets. In this case, U.S. government bonds, U.S. Agency bonds, or other obligations are placed in a bank escrow account created solely to meet the interest and principal requirements of the outstanding municipal bonds. Prerefunded bonds—popularly dubbed "pre-rees"—are priced to the first call date when they will be redeemed. Although many traders assume escrowed bonds are protected from early calls, several loopholes allow the occasional early recall of these bonds.

A recent addition to municipal bond offerings is an inflation-linked bond that began its infancy in a 1997 sewer revenue deal. Like their cousins Treasury TIPS and corporate inflation-linked bonds, they are linked to the Consumer Price Index. Since they are not well-known, there is not much demand for them if you decide to sell. For a description of how they work, refer to the description of TIPS in chapter 6.

You can purchase munis from large all-purpose brokers or through bond boutique houses. The buyer must pay for the bonds three days after the date of purchase, unless they are new issues. A buyer may have a week to a month to pay for the bonds once the sale has been confirmed. The approximate settlement date of the trade is established at the time of sale.

Since most municipals trade infrequently, municipal traders in the secondary market use price matrixes to determine what a bond is worth. Traders see where other similar bonds are trading and price the bonds accordingly. Brokerage houses use the price matrix to evaluate a bond portfolio. This approach is like pricing an existing house for sale by looking at what comparable houses have sold for recently. In an unstable market, those prices can be very misleading.

In this book, we broadly group municipal bonds by their taxable status: taxable munis, which are completely taxable even though municipalities issue them; private activity bonds, which are subject to the alternative minimum tax; tax-exempt municipal bonds, which are not subject to federal income tax, and sometimes not to state income tax as well. Included in the tax-exempt group are the major categories of general obligation bonds and revenue bonds.

Because there are taxable munis as well as tax-exempt munis, it's important to be aware of the differences so that you can benefit the most. Taxable munis are just that—fully taxable. Some munis are subject to the alternative minimum tax. If you're not subject to that tax, then you can benefit from the higher yield on these bonds.

But even tax-exempt munis may be subject to some tax, which you should take into account in your financial planning. For example, many states subject bonds issued by other states to state and local taxes. If you live in a high-tax state like New York, it probably would not be tax efficient to purchase bonds issued by another state. This is especially true if you live in New York City, where New York State bonds give you "triple-tax-exemption," and bonds of any other state would give you an exemption only from federal taxes. Some taxpayers are challenging these laws, insisting that they are unconstitutional. We will have to wait for the Supreme Court to decide the ultimate outcome.

Tax-exempt munis can also be subject to some tax if you purchase them in the used bond market at a market discount, meaning for less than face value. According to the The Bond Market Association's Web site, bonds bought at a discount may be subject to capital gain or ordinary income tax depending on whether they are subject to the de minimus rule. Since this explanation is very technical, please visit www.investinginbonds.com, choose the tab on the top labeled "Learn More," then choose "Municipals," and finally "Taxes and Market Discount on Tax-Exempts." You may also want to look at "Taxation of Municipal Bonds." If you are not computer savvy, you can write to us and we will send them to you. Be aware that even your adviser may not fully understand these very complicated rules.

All municipal bonds may be subject to a capital gain or a capital loss when you sell or redeem them. You should consult with your tax adviser to determine whether it might be advantageous for you to sell your bonds before redemption. When the purpose of a sale is to get a tax benefit, this is called a "tax swap," discussed in chapter 19.

How do you determine whether to purchase tax-exempt municipal bonds or taxable bonds for your cash account? The greater your taxable income and the higher your tax bracket, the more likely you will seek shelter in the municipal bond market. The general rule is that when computing the tax benefit, it's assumed that any state and local income tax paid will reduce the amount of federal tax because the state tax is deductible on your federal tax return. There is an exception to this rule: If you're subject to the AMT, you will not receive the benefit of the state taxes as a deduction on your federal income tax return.

If you earned $100,000 in taxable income in 2006 and filed a joint federal income tax return, your 5 percent yield would be equal to a 6.67 percent pretax equivalent return in Florida, where there is no state income tax, and a 7.45 percent pretax equivalent return in New York City, where there are high state and city taxes. If you are subject to the AMT, this calculation would be different.

You need to determine if it is more advantageous for you to purchase taxable bonds or tax-exempt bonds. On the Web site www.investinginbonds.com, you can enter your taxable income from your tax return. The calculator will compute your federal income and state income tax rate, and your total effective rate. Note that the Web site does not take into account any local taxes you might pay nor AMT. Based on those tax rates, the calculator will provide you taxable equivalents for tax-exempt yields beginning at 1 percent for taxpayers filing single or jointly. When you use these rates to compare a tax-exempt bond to a taxable one, be sure to compare apples to apples. The rating quality and call structure should be similar for the comparison to be justified.

You can also use the calculation in Figure 10.2 to determine your taxable equivalent yield, but the calculator on the Web site is so much easier.

Assume that you were offered a 4 percent tax-exempt bond return and wanted to know how that would compare to a taxable bond return. Convert the yield to a decimal by dividing 4 by 100, thus 4 percent is expressed as .04. Assume that your effective tax rate is 25 percent. Change that to a decimal and subtract it from the number 1 to get the reciprocal of your tax bracket (1 - .25 = .75). As indicated in Figure 10.2, divide .04 by .75 and the result is .0533. Turn the decimal back into a percent by multiplying by 100 and you will find that your 4 percent tax-exempt yield is equal to a 5.3 percent taxable return. This is called your tax-equivalent yield. If you were offered a taxable bond of the same quality, with a yield higher than 5.3 percent, you might purchase that in lieu of the tax-exempt bond yielding 4 percent.

In most states if you purchase bonds sold by an issuer within that state, the interest income is exempt from federal, state, and local income taxes. In those states that have income taxes and an exemption for in-state municipal bond interest, it's usually better to purchase in-state bonds, as in the high-tax states of New York and California.

Some states do not tax the interest income from bonds sold by an out-of-state issuer. In those states, it does not matter whether the issuer is in state or not. The same would apply if your home state taxed all tax-exempt municipal bonds equally, no matter what the state of the issuer.

Municipalities have issued a large amount—about $60 billion worth—of taxable muni bonds that are subject to federal income tax. These bonds have been on the scene since 1986 and are the result of the federal government's attempt to limit the use of the municipal tax exemption. These bonds are issued for private purposes that are not eligible for tax exemption, such as stadiums funded by gate receipts, investor-led housing, privately operated toll roads, and pension funds. Lease-revenue bonds can also be taxable if the private sector is occupying public space.

Municipal debt subject to federal income tax may be free of taxes in the state of issuance. Pennsylvania residents, for example, don't have to pay state taxes on the interest derived from taxable munis issued in their state. This feature gives taxable municipal debt a leg up when compared to corporate debt or CDs. In addition, taxable munis may be insured, unlike most corporate bonds.

Although they're not really a risk, you'll find that taxable munis are not widely available because insurance companies and banks usually buy up the issues. Many brokers do not sell them at all—which leads to the next problem, namely liquidity. Because they are not plentiful, they do not trade well. Do not plan on buying them to resell.

Taxable munis are subject to federal and, for nonresidents, state and local income taxes. If you purchase bonds issued in your state of residence, they may be exempt from state income taxes.

Insured! That's what a majority of taxable municipal debt is, and that's always a great comfort. Most other taxable bonds are not insured. Like other municipal debt, taxable munis can be prerefunded to their earliest call date. Taxable municipal debt may have fixed calls. When we compare taxable munis to corporate bonds, the risk/reward ratio says buy insured taxable munis whenever possible.

Private activity is a relatively new designation, describing bonds that are subject to the AMT. One of two aspects of a bond will trigger this designation: (1) more than 10 percent of the proceeds will be directly used for private trade or business, or (2) more than five percent of the proceeds will be loaned to private entities.

Since January 2002, school districts became free to issue private activity bonds for school construction purposes. Unlike general obligation or revenue school bonds, discussed later, these bonds are subject to the AMT. This development reflects the takeover of public schools by private companies, such as Edison Schools, and the addition of charter schools operating within public school districts.

Private activity bonds provide a real benefit to you if you are not subject to the AMT. They provide a higher return because so many muni buyers do not find it advantageous, in tax terms, to purchase them.

One very risky category of private activity bond goes by the name of the industrial development bond (IDB). These bonds are issued for economic development and pollution control, including solid waste and resource recovery issues in which private entities are responsible for debt service. Of all the types of bonds issued, these have had the highest default rate in recent history, representing 29 percent of the defaulted debt during the 1990s, according to a Standard & Poor's 2001 study. Along with health care, this sector continued to be risky in 2007.

In a 2003 update of its default study, Fitch found that the cumulative default rate for IDBs between 1980 and 2002 was 14.62 percent, by far the largest category of municipal defaults. However, the report notes that although single-family and multifamily housing have higher-than-average default rates, they also have higher-than-average recovery rates (68.33 percent based on the number of defaults) because of the collateral backing of most of these transactions. This rate is higher than for public corporate bonds, which have a recovery rate of 40 percent.[64] Most of those bonds were unrated. Muni bonds subject to the AMT are less liquid than other tax-exempt munis.

The most compelling feature of tax-exempt bonds is their immunity from federal income taxes. However, although tax-exempt bonds are exempt from federal income taxes, they are not uniformly exempt from state and local taxes. Only bonds issued by U.S. territories, namely Guam, the Virgin Islands, and Puerto Rico, are tax-exempt in all states. That's the good news. Unfortunately, they are weak credits, with Puerto Rico the strongest of the three. Using the services of a knowledgeable bond broker or a financial adviser may be the best way to take advantage of the tax breaks inherent in munis.

There are two categories of bonds that finance traditional government responsibilities: general obligation (GO), which are supported by the taxing power of the issuing entity, and revenue bonds, which are supported by specified revenue streams, generally consisting of fees paid by users of the project being financed. Sometimes they are jointly financed.

Until the late twentieth century, GO bonds constituted the majority of issued munis. Then they slowly began to fall out of favor as governments found it politically more acceptable to issue debt backed by dedicated streams of revenues rather than general tax receipts. Furthermore, GO bonds have to be approved by public referendum whereas revenue bonds do not.

It's important to know the kind of tax-exempt bond you may be purchasing. The following are capsule descriptions highlighting the advantages and risks of the many choices offered among GO and revenue bonds. As with all bonds, it's essential to check the rating before you commit to buying these types of munis.

Unless specifically limited by law, the full faith and credit and all the financial resources of the issuer back these GO bonds.

Municipalities of any kind and size may issue GO bonds, from the largest state to the smallest township. Bonds backed by the broadest taxing power are called unlimited tax GO bonds (UTGO bonds). Sometimes a specific taxing power supports munis. These are called limited tax GO bonds (LTGO bonds). Voters might support a limited tax designated for the construction of a prison, for example.

An issuer's strength is based on the breadth of its tax base—a diversified economy drawing from many revenue sources—and a low level of debt. States, as opposed to counties and municipalities such as towns and cities, generally feature the broadest tax base and the most flexibility, and this is reflected in the ratings assigned to their bonds. As a result, they tend to be rated AA or better.

School district (SD) bonds, issued for school construction and other educational requirements, employ a variety of revenue sources and may be classified as GO, revenue, or private activity bonds. School district bonds are GO bonds that are generally backed by real estate taxes and frequently state support as well. Pennsylvania and Arkansas, for example, have state intercept programs that direct state aid to bond payments in the event the school district cannot meet its obligations. Texas has a Permanent School Fund based on oil revenues, real estate, stocks, and other investments to back the debt of its schools.

General obligation SD bonds are similar but distinct from Public School Building Authority bonds. The latter are revenue bonds. The authority represents many schools at one time; however, the bonds are usually the responsibility of the specific school for which the debt is issued. They pay the authority, and the authority pays the trustee who directs the paying agent to pay you. The quality of the schools and the price determine whether these bonds are a good buy.

Advantages. Fitch ranked GO bonds among the safest in a 2003 study, with a cumulative default rate of .25 percent during a sixteen- to twenty-three-year period. Moody's has had no material payment default since 1970 on the bonds it has rated.[65] Since these bonds require voter approval, they come with a broad commitment for debt repayment.

State debt sells well because of its sterling track record, no matter what the rating. This means that should you need cash, you should be able to quickly sell a state GO at a reasonable price. State legislatures limit the amount of school district GO bonds that can be issued by raising the bar regulating the percentage of voters who must approve a bond issue. As such, these bonds are generally viewed as very safe debt because they are voter approved and supported by real estate taxes.

Risks. The advent of a recession and the consequent drop in tax revenues from all sources pose one of the greatest risks to GO bonds. In addition, serious restrictions can be put on the ability of legislatures to raise taxes. An issue raised by Hurricane Katrina's devastation of New Orleans and the surrounding area was what happens to GO bonds when there are no longer as many residents to pay taxes and support the debt services. The actual outcome was that a massive influx of funds from all levels of government and private sources supported all the debts. None of the bonds defaulted.

Special Features and Tips. GO bonds tend to be very "clean." That means they do not have many special provisions, and there are no long stories required to describe them. GO bonds generally do not have extraordinary calls. Buy state GO bonds whenever possible unless state politics take the bloom off the rose.

State GO bonds are generally more liquid because they are known quantities and very safe. Given this reputation, there is generally a smaller spread between the asking and selling price. The next best buys are GO school district bonds and those issued by counties, cities, and local governments.

School district GO bonds may be small, bank-qualified (BQ) deals meaning that banks may legally purchase the bonds. The BQ deals are issued for less than $10 million, usually with five-year calls, or they may be larger deals with ten-year call protection.

Specified revenue streams support revenue bonds. Their rise in popularity over the past few decades has led to the creation of several variations and twists on how entities can package and sell bonds. The issuing entity is the key distinguishing factor among municipal revenue bonds. As such, knowledge about this entity should help you distinguish, for example, among three AAA-rated insured bonds with one supporting a housing development, another a stadium, and the third an electric utility. In good times, it probably won't matter what you buy. However, when unemployment is rising, sales are dropping, and mortgages are defaulting, how you allocate your assets makes a difference. Remember, traders consider the underlying ratings of insured bonds and value them accordingly.

What follows are the various bond packaging approaches now used.

Authorities. These are political entities, originally thought to be above the influence of politics, which are conduits for the issuance of bonds. Huge governmental conglomerates, known as authorities, issue revenue bonds for transportation, water and sewer, housing, and other purposes.

The word authorities originated in England, when the creators of the Port of London sought a way to differentiate it from other entities. In the enabling legislation where the powers of the port were granted, the document repeatedly referred to the word authority, as in "Authority is hereby given."[66] In the United States, the use of authorities to issue debt began in 1921 with the formation of the Port of New York Authority (later renamed the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey). After 1960, when revenue bonds began to replace GO bonds, authorities became more prevalent.

Bond banks. Bond banks are entities structured by states to lower the cost and to improve the marketability of debt issued by small municipalities. The banks purchase bonds from the municipalities with funds raised through the sale of their own bonds. The local municipalities then repay the bond bank.

Leases. Leases back bonds when a municipality or its agency issues bonds to build a facility and then leases it to a state agency. The rent paid is sufficient to pay off the bonds, at which time the lessee is usually granted the right to purchase the facility for a nominal sum. A possible hitch in this scheme is that the rent payments usually depend on the vagaries of annual appropriations in the state's budget, although facility usage fees may also support the debt. If the money is not appropriated, the bonds will be called. The investor is at risk if the money is not appropriated.

When issued by the state, lease debt is usually rated one notch below that given to the sponsoring state's general-obligation debt. In some states, leaseholders may not have priority status as creditors in bankruptcy situations without taking action in court.[67]

On a cautionary note, in 2002 Kmart filed for bankruptcy, and $215.2 million worth of lease-backed and mortgage-revenue bonds originally issued in 1981 went into default. Although the bonds backed by mortgages were expected to fare better, those backed by leases of closed stores had no value. Since 1986, municipal issuers are no longer permitted to sell bonds backed by retail stores.

In an interesting twist, investment bankers have found the lease structure to be acceptable to some segments of the Muslim community as backing for a bond issue. Under Shari'a law, interest payments are unacceptable. To float a $600 million Malaysian government global bond issue, HSBC holding company structured the deal as follows: Malaysia's federal land commission was to sell the property (including the building housing the Ministry of Finance) to a special-purpose company, which would then lease the property back to the government. Investors in the bond would buy the land from the special-purpose company and were to be paid the lease proceeds every six months. The lease payment was to correspond to the interest rate that London banks use to lend each other money. Upon the bond's maturity, the bond investors would sell the land back to the special-purpose company and get back their principal, while the special-purpose company would sell the land back to the government. Although there was some concern about the interest component of this deal, the structure received approval from Islamic scholars in Malaysia, Dubai, and Bahrain who were "very pragmatic" because they did not want to throttle Islamic Finance at birth.'[68] Large U.S. banks want to be enthusiastic participants in issuing this type of bond, which may result in their being included in the foreign bond category. Certificates of participation. COPs are debt instruments that are typically backed by lease payments, although they are legally different from bonds. Like leases, COPs require annual appropriations by the state legislature. There have been rare attempts by issuers to renege on these obligations. The most infamous was in AA-rated Orange County, California, when citizens voted down a sales tax increase to pay for losses in an investment portfolio and the county filed for bankruptcy in 1994. In 1989, citizens of Brevard County, Florida, tried to walk away from COPs backing a municipal building because they did not like its location. Eventually, the pressure of the bond market rating and insurance companies led to the refinancing of these bonds.

Special tax districts. These districts provide infrastructure improvements for residential and/or commercial real estate development. In Colorado, they are called special improvement districts. Florida calls them community development districts. In Texas, special sewer districts are called municipal utility districts (MUDs). These districts are based on the idea, "Build it and they will come." Alas, they don't always come. Problems arise more frequently with these kinds of loans than with more traditional munis. Frequent defaults in Texas brought stringent requirements for debt issuance in 1997, resulting in investment-grade ratings for some of these projects and more oversight overall.[69]

Let's look now at the major types of revenue bonds issued by various entities and consider their advantages and risks.

Airport bonds. See transportation bonds.

Charter school bonds. See education bonds.

Convention and casino bonds. See entertainment industry bonds.

Education bonds. Charter schools are private schools that receive funding from the existing school districts and federal funds through the Department of Education. Each state must separately authorize the establishment of charter schools, and the terms of the charters vary. As of September 2006, forty states and the District of Columbia had authorized charter schools.[70] Unlike public schools, charter schools can go out of business, although such failures are generally the result of poor management or financial disorder.[71]

School construction may be financed through the establishment of a lease issued by an authority or a building corporation. Grants from the federal government, as well as from the school district in which the charter was granted, and student fees provide funding. Charter school bonds may be more likely to attract an investment-grade rating if their main purpose is to relieve overcrowding. Some charter schools have secured insurance for their bond issues as well.

Bonds for colleges and universities are usually issued under the auspices of state authorities. The authorities are pass-through entities enabling the debt to be issued. The security for college and university bonds is based on a variety of income sources. They include government grants and private endowments, revenue from student housing rents, private and federal research contracts, and entertainment, such as sporting events and theatrical productions. The bonds that receive the highest ratings are those issued by larger, well-known institutions that are better endowed and more financially secure than smaller, less influential schools. State-supported schools get funding from state appropriations, student enrollment fees, and other sources.

Advantages. School district bonds are considered the backbone of any conservative portfolio. Buying college and university debt adds diversity to your portfolio. Public higher-education debt was deemed to be the least risky class of debt in this category by Fitch in its 1999 study and confirmed by Moody's own sources in 2006.[72]

Risks. The downside of charter school bonds is that, for the most part, they have no track record. Their survival could be threatened if existing school districts are able to restructure and reform. Fitch points out that the waiting lists at charter schools could evaporate if students were attracted to a public school with a strong athletic program or some other special features. Poor community relations, publicity, governance, leadership, or a negative demographic change could affect the charter school's viability.[73] For these reasons, existing charter school debt is mostly classified as high risk.

For higher-education bonds, in addition to the usual risks such as poor fiscal management and declining enrollment, the primary risk is that the cost of education will outweigh the perceived benefits. In an economic downturn, private colleges with small endowments may have difficulties staying afloat.

Special features and tips. Do not confuse junior college debt with community college debt. The former is private; the latter public. A junior college may or may not be well endowed. Privately funded junior college debt, therefore, may not be as strong a credit as publicly funded community college debt.

Entertainment industry bonds. Municipalities, particularly those in urban areas, find it beneficial to attract tourists and suburban residents to downtown hotels, restaurants, and stores. They do so by sponsoring the construction of convention centers, cultural centers, and sports arenas to draw these outside spenders. Entertainment debt supports such construction activities, and dedicated tax revenues and usage fees fund them.

Advantages. Municipal officials view stadiums, hotels, golf courses, and convention centers as ways to jump-start a depressed area. As such, municipalities are committed to their establishment. For example, in 2006 the Internal Revenue Service approved the financing for two stadiums in New York City issued by the Industrial Development Agency (IDA), wherein payments in lieu of taxes (PILOTs) would back the bonds.[74] Typically, PILOTs are used to help otherwise exempt entities, such as governments, schools, and hospitals, by purchasing land and then allowing the entity to use it at below current tax rates. The New York Mets and Yankees were allowed to issue PILOTs because their payments to the city were to be considered the equivalent of taxes.[75]

Risks. Declines in economic activity can adversely affect both dedicated taxes (such as hotel occupancy taxes) and usage-fee revenues. The problem may be that the revenue projections were overly optimistic. The Sheraton Grand Hotel in Sacramento had an above-average industry occupancy rate and room rate. However, the actual room rate was $122.86, whereas the projected room rate was $145, so the city did not have enough funds to pay for the first debt-obligation payment due in 2006.[76] Furthermore, this hotel was supposed to spur use of the adjacent convention center, which it did not. According to Heywood Sanders, a professor in the department of public administration at the University of Texas at San Antonio, the convention center business is declining, and adjacent hotels are not a catalyst for greater use.[77] Yet public officials still follow the motto: "Build it and they will come."

Tribal casino debt has its own unique issues. Since Native American tribes are sovereign countries that exist within the United States, it is not clear if a debt can be collected if there is a dispute. Many tribal governments are in disarray, and the reservations are economically impoverished. Not all tribal debt is of the same caliber. Many states have been crafting agreements with tribal governments to permit the opening of casinos.[78]

Special features and tips. We don't like to purchase bonds that are issued to fund anything not essential to a community. Although you may consider attending a sporting event or playing golf essential when times are good, in hard times that may not be the case. Insurance is highly advisable when considering investing in entertainment deals because you can't judge the likelihood of their ongoing success.

Health care and hospital bonds. Hospitals have a continual need to upgrade facilities and buy new equipment. Bonds to finance many of these improvements are issued through state health authorities, which act as financing conduits for hospitals as well as for nursing homes and the relatively new continuing-care retirement communities (CCRCs). Bonds for the latter, which are residences for elderly citizens who require some assistance, are frequently not rated. According to Fitch, it is expected that the financial stability of this sector will remain stable as the baby boomers purchase these services. The older CCRCs will have to upgrade and expand to meet the competition, placing a drag on profits.[79] Nursing home bonds also are frequently nonrated. Whether or not the bonds are rated, the issuing authorities assume no responsibility for the repayment of their issues. The responsibility rests with the health care facilities for which the bonds were issued.

Advantages. Comparatively higher yield is the advantage of purchasing CCRCs and nursing home bonds, especially when they are unrated. Typically, hospital bonds yield more than similarly rated GO bonds.

Risks. The financial health of hospitals has stabilized after reeling under the onslaught of rising costs and restricted managed-care payments. However, health care bonds are viewed as risky. In the event of a default, hospitals are likely to be liquidated or sold, resulting in a 75 percent to a 100 percent loss in bond value.[80] In Standard & Poor's study of defaults in the 1990s, it was primarily the nonrated bonds in this sector that defaulted, with nursing home bonds defaulting more frequently than any other type. Insurance companies paid if the bonds were insured. If you're considering buying nonrated bonds, it is essential to know a good deal about the issuer.

Special features and tips. Hospital bonds are subject to extraordinary calls in addition to regular calls. They also may have sinking funds. The higher yields resulting from downgrades can make hospital bonds attractive for junk bond buyers. Insurance may reduce some of their characteristic risk, but remember: insurance does not make a bad bond good.

The long-term financial viability of CCRCs remains to be proven, and bonds for their purposes are relegated to the high-yield market. CCRCs supported by financially solvent religious and nonprofit institutions are more attractive than those without such backing.

Highway bonds. See transportation bonds.

Housing bonds. Municipal housing bonds support the creation of multifamily or individual housing units for the poor and elderly. There are three kinds, each having a different purpose and special security provisions. All are managed through state and local housing finance agencies.

State housing agencies float bonds for builders of multiunit apartment buildings for the elderly. Some of these have federal insurance and are very creditworthy. The others are difficult to evaluate.

State housing finance agencies sell bonds to secure funds for the purchase of mostly single-family mortgages from banking institutions. The mortgage revenue and a variety of insurance policies back these bonds.

Local housing authority bonds support the development of multiunit apartment buildings and are secured by comprehensive rent subsidy packages.

Underlying mortgages fund housing bonds, and the federal government may insure or subsidize these bonds. Federally insured housing bonds are rated AA or AAA, depending on the extent of the coverage provided by the FHA or the VA. HUD subsidizes rent payments for qualified individuals. Some housing bonds also carry a moral obligation pledge from the state that issues them. In addition, there may be insurance on the properties in case they are damaged or destroyed and insurance on the contractors for proper performance in construction.

Although single-family mortgage bonds are quite safe from default, they have a very high probability of being called away early. "Supersinkers" are single-family mortgage-revenue bonds with maturities between twenty and thirty years that will probably be redeemed within ten years. A sharp drop in interest rates could result in bond calls after a year. In extreme cases, this could result in a cash shortfall if the revenue fund did not appreciate sufficiently to pay the costs of bond issuance.

Advantages. Housing bonds for single-family homes tend to have higher yields than other munis. Default risk is minimized on housing bonds that carry federal support and other kinds of insurance. State housing authorities have rigorous underwriting standards. Many multifamily housing deals are backed by federal insurance, carry an A to AA rating, and have additional private insurance as well.

Risks. Although federal rent subsidies provide a reliable stream of income supporting multifamily housing bonds, HUD reserves the right to stop paying if the rental unit is vacant for more than a year or if the housing administration does not follow HUD rules. Public Housing Authority bonds issued in anticipation of federal payments from HUD run the risk that the funds to pay the debt service will not be appropriated in sufficient amounts. However, expecting that this might be a problem, the issuer can build in safeguards. The rating should reflect them.

Housing bonds are subject to unpredictable, so-called extraordinary calls that can occur any time after the bonds are issued. Some bonds might be called from unexpended proceeds. In this case, the issuer would be unable to use all the money that the bond issue raised. Bonds can also be called because the mortgages backing the bonds have been retired. When interest rates are declining, calls tend to increase with home refinancing activity.

Special features and tips. Cautious buyers should purchase single-family mortgage revenue bonds at or near par due to the likelihood that they will be called away early through an extraordinary call. For this reason, they have limited upside price potential. However, if you purchase them at a discount and they are called early, you may have an unexpected gain. Your gain may be subject to ordinary income tax. Multifamily bonds have a much lower pre-payment risk than single-family housing bonds.

Along with tax-exempt bonds, housing agencies may issue some taxable debt that is subject to the AMT. These bonds have higher yields than bonds not subject to this tax.

Supersinkers and high-coupon housing bonds are attractive to investors who prefer the high yield of long-term bonds and are willing to deal with unpredictable early calls. When prepayments slow because of rising interest rates, housing bonds with high coupons can be good performers as the ample cash flow continues for a longer period of time. In the first half of 2005, pre-payments varied from one state to another, with the West having the highest rate of prepayment, followed by the Mid-Atlantic and New England regions. Florida was the fourth fastest of all states in the nation, while the South in general had the slowest prepayment speed.[81]

Nursing home bonds. See health care and hospital bonds.

Public power bonds. Public power bonds were initially floated to subsidize electrification of underdeveloped rural areas of the country. The use of municipal bonds for this purpose began in the 1930s in California, Nebraska, and the Northwest. The first authority that grew out of federal legislation aimed to harness the Columbia River to produce hydroelectric power.[82] One of the major bond defaults of the twentieth century occurred when the Washington Public Power Supply System undertook the construction of five nuclear power plants to supplement that power. Municipal electric utilities have thrived since the turbulence of deregulation derailed some of the investor-owned utilities in 2002.

Advantages. Formerly included in every widow and orphan portfolio, electric utility bonds fund a basic need to supply heat, cooling, and light for homes and businesses. Some very well-managed utilities issue debt; however, one needs to pick and choose carefully today to find a power bond with both an attractive yield and protection against default.

Risks. A power provider must comply with federal and state regulations, restricting its flexibility. Deregulation of the power industry in California, for example, led to runaway costs for the utilities while limiting the prices charged to consumers. California Edison teetered on the brink, and Pacific Gas and Electric declared bankruptcy. Although all muni bonds are subject to changes in political climates, the years 2000 and 2001 highlighted the particular vulnerability of investor-owned public power bonds to this risk factor.

Special features and tips. Like other revenue bonds, utility bonds are subject to extraordinary calls that could result in their being called away early.

Tobacco bonds. An arrangement between R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co., Philip Morris Inc., and Brown and Williamson Tobacco Corp. and forty-six states established by a master settlement agreement has given those states the right to payments from tobacco profits for twenty-five years. The process of issuing bonds to access the use of the anticipated revenue is called securitization. States depend on the revenues produced by this arrangement, forming uneasy bedfellows. In August 2006, a federal judge found that the tobacco companies violated federal racketeering laws, ordered them to admit that they had lied about the hazards of smoking, and ruled that they must warn consumers that cigarettes are addictive. The judge did not penalize the tobacco companies for past actions, thus, protecting the outstanding municipal bonds backed by tobacco revenues.

Tobacco bonds typically have a Baa3/BBB rating. Their value has fluctuated widely as suits against the tobacco companies have alternatively been won and lost. But not all tobacco bonds are the same. Only tobacco proceeds or tobacco proceeds mixed with other revenue sources may secure the debt service. Arkansas, for example, has issued revenue bonds with only 5 percent of the proceeds coming from tobacco.[83]

Advantages. There are two advantages of purchasing tobacco bonds: They tend to offer higher yields than other munis, and they also provide an element of diversification to a bond portfolio. According to the Government Accountability Office, forty-six states that were part of the tobacco settlement received $5.8 billion in 2005, about a third of which supported health-related programs. The remainder supported debt repayment or was added to the general fund of the states.

Risks. Although the current stream of income from tobacco is quite good, revenue will decline if and when people stop smoking. The revenue could also be undermined if huge punitive damages are awarded to plaintiffs in malpractice suits. Given the special nature of these bonds, they are not as liquid as other types of munis. If you are a buy-and-hold investor, that is not a problem.

Special features and tips. Authorities were created specifically to issue the large deals backed only by the tobacco revenue, passing on the risk and the reward to you. You have to decide if you're being compensated well enough for that transfer of risk with the extra 30 to 40 basis points you're paid for buying tobacco bonds. Tobacco bonds may be structured more like mortgage bonds, rather than straight debt. Some bonds have "turbocharged" redemption provisions so they are best purchased at par or at a discount.

Transportation bonds. Transportation authorities engage in just about every aspect of bringing goods and services into and out of a region. Some even include real estate activities among their portfolios. Transportation bonds include bonds issued for ports, roads, trains and buses, and airports. A key factor in considering transportation bonds is not the name of the authority issuing them but rather what entity is paying for them. Highway revenue bonds, for example, are of two types: toll road bonds and public highway improvement bonds. Earmarked funds from gasoline taxes, automobile registration payments, and driver license fees finance public highway improvement bonds. However, as fuel efficiency reduces the amount of gasoline used, the taxes collected for the sale of fuel are reduced. In addition, the historical reluctance to increase taxes or to have the tax keep pace with inflation has put pressure on highway trust funds to meet ever-burgeoning needs, according to Standard & Poor's.[84]

As a result, the transportation arena has been forming public/private partnerships to finance the construction, operation, and maintenance of our nation's crumbling infrastructure. These partnerships will change the way future revenues are predicted and will add the complication of payment to equity investors as well as debt repayment.[85] For the states, it is a way of "outsourcing political will," said Representative Peter DeFazio (D-Oregon) in June 2006, expressing concern about the Indiana toll road privatization. However, in its defense, Governor Mitch Daniels said that tolls had not been raised since 1985 and that the privatization would enable Indiana to finance road improvements that it otherwise could not afford.[86] The road was privatized later in 2006, and other states are considering following suit.

A recent source of funds available to states for accelerating road and bridge construction is from grant revenue anticipation notes, an expectation of payments from federal grants. These so-called "Garvees" are used in conjunction with other sources of bond payments because federal transportation funds used to back such debt are subject to reauthorization by Congress every six years. As a result, the shorter maturity debt in such issues is viewed more favorably from a credit perspective.[87]

Trains and buses rely on usage fees to fund their bonds, although federal grants are occasionally available for such purposes. One current federal program, dubbed Bus Rapid Transit, supports the construction of bus-only lanes, traffic lights that stay green as a bus approaches, and bus-boarding platforms, among other ideas.

Three different sources of revenue finance airport bonds: (1) ticket fees paid by passengers, (2) a wide number of airport usage fees (including flight fees paid by airlines for air travel; concession fees paid by shops, stands, and restaurants; parking fees; and fueling fees), and (3) lease income from the use of hangars or terminals. The wave of airline bankruptcies has tested the structure of the leases in the bond covenants. At the Denver airport, the bonds were tied to a true lease, while at three other airports the leases were recharacterized as loans or financings, letting the airlines off the hook for their special-facility revenue debt in 2006.[88] This is expected to increase the cost of financing and raise the yields on such debt.

Advantages. Transportation bonds represent the full range of credit quality, from established, broad-based issuers and solid debt coverage at one end to some of the more vulnerable issuers with lower collateralization and coverage on the other. Investors can pick up some high yields here, but you always have to balance the yields with their risk.

Risks. Downgrade and default are possible for transportation bonds funded by revenues. For example, in 2007 bankrupt Delta Airlines planned to eliminate "at least $1.2 billion of its $1.7 billion of tax-exempt debt. Holders of unsecured claims, the category that some special facilities revenue bonds will fall into, would receive a payout of between 63 and 80 percent under the plan."[89]

Although reliable streams of income support most revenue bonds, the issuers may be overtaken by adverse political actions and events beyond their control. Since the destruction of the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001, the realization that the United States may be a target of Islamic terrorists has cast a cloud on all transportation issues. Security has been added to protect our ports, airports, and other transportation conduits, but the possibility of terrorist acts, which always existed, has become more immediate.

Special features and tips. Owners of struggling toll road bonds can see the value of their holdings rebound if the toll road is leased to a private entity. This was the case in the Richmond, Virginia, area. "Pocahontas Parkway Association senior bonds traded as low as 64 cents on the dollar, rebounding to 104, as investors anticipated the possible defeasance of the bonds," said Philip Villaluz, vice president for municipal research at Merrill Lynch & Co.[90] The low bond price can be explained by a 2002 study by Robert Muller of J.P. Morgan Securities, which examined toll road issuance and concluded that "more than half of all 'project finance type' [start-up toll road] feasibility studies overestimate their [revenue] forecasts by a substantial margin."[91]

Transportation bonds usually have extraordinary calls that can be exercised in the event of a catastrophe. Sometimes they have stated calls and sinking funds. When considering transportation issues, ask yourself if you would use the services being provided by the issuer and backed by the bonds. Ask also if there are any alternative providers of the same service in the same area.

Water and sewer bonds. Water and sewers are essential to civilized living, and the entities that provide these services have little trouble collecting bills. In addition to usage fees, water and sewer districts charge assessment fees to determine the placement of the sewers and connecting fees that are collected before the sewers are built. The water and sewer bonds issued to support these activities are generally regarded as being among the safest municipal investments, a finding confirmed by Fitch in its 1999 study and reaffirmed in 2003. Moody's also affirmed this finding in 2006.[92] Standard & Poor's notes that "the general governmental sectors of tax-secured [bonds] and utilities are the most stable of all [municipal bond] sectors."[93] A municipality, or in the case of the wastewater bonds municipalities within a given area, generally issues these bonds. An authority, a water conservancy district, or a state bond bank may also issue bonds. Bonds issued through a state bond bank may carry a moral obligation pledge protecting cash flow against loan defaults. When the funding source is the federal government, the money is channeled into a state infrastructure bank, and the municipal project is subject to state and federal guidelines.

Advantages. Considered, as was noted, among the safest of municipal investments, water and sewer bonds are often double-barreled. The payment sources for the bonds are twofold: the revenue from water usage and a pledge of the municipality's tax revenue. Such double-barreled bonds may be sold as general-obligation bonds or, with a more restricted revenue source, as limited-tax general-obligation bonds.

Risks. These bonds come with a wide range of ratings, each determined by how established an area is and the solvency of customers who will pay for the bonds. As with other types of bonds, start-up situations tend to be riskier than bonds floated for repairs of established systems. Texas MUDs are special taxing districts that often sell nonrated debt in order to jump-start a development project.

Default potential is higher in areas where utilities are not allowed to discontinue service even in the event of nonpayment of bills. Problems might also arise if bonds financed an existing antiquated system, in that more money than initially projected might be required to repair it. Furthermore, utilities must provide for water even in the face of prolonged drought conditions.

Note that the introduction of conservation programs can cause a decline in revenue. Changes in legislation can also negatively affect water revenue if payments for purchased water are somehow restricted. For example, a Utah state senator proposed legislation in 2001 that would prevent the use of property tax revenue for the repayment of water and sewer bonds, reasoning that the tax lowered the cost of water, thus, encouraging careless consumption. If that legislation had passed, it would have undermined the credit quality of future water and sewer bond issues in the state. Sometimes legislation undermining rates causes problems. A 2006 decision in California agreed that Proposition 218 passed in 1996 gave voters the right to petition for a ballot initiative to lower the rates of a public water district. However, the water agency had the right to raise other fees or create new fees so they are not particularly concerned it will be a problem.

Special tips and features. Traders value water bonds more than sewer bonds, and sewer bonds more than wastewater bonds, although they may be offered to you at the same yield. MUDs with investment-grade ratings must compete with other similarly rated bonds, but buyers are wary because of the unsavory history of defaults on unrated paper. That results in higher yields for those willing to take the risk.[94]

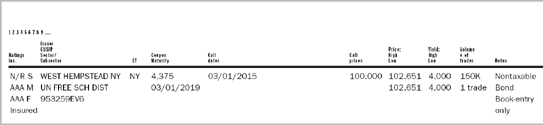

Using www.investinginbonds.com for municipals bonds is fairly easy once you know your way around. Click on "Municipal Markets-at-a-Glance" and choose either today's or yesterday's prices. You can choose a state of issuance and then sort the bonds by maturity, issuer, CUSIP, trade time, price, or yield. This is helpful if you are seeking general market conditions. Figure 10.3 presents a view of a municipal bond screen with only one bond included.

In Figure 10.3, the column on the left gives you the Standard & Poor's, Moody's, and Fitch ratings. "N/R" means the bond is not rated. In the next column, you're given the issuer, then the CUSIP, and finally for revenue bonds you're given a sector, like hospitals or transportation, so you'll know the purpose for which the bonds were issued. Click on the highlighted CUSIP, and you'll get more information about the bonds. ST tells you the issuing state. Coupon and maturity are next, followed by the call date and price. The site gives you the high and low trade for the day, although it's not unusual for there to be no trades or only one. Then you see the high and low yield, in this case 4 percent. In this example, there was one trade for $150,000. Then you are told that this security is nontaxable, a bond and book-entry only. If there is any more information, it would appear in the next column. You can see the history of yesterday's trades only or a full history. You can also view the prospectus by clicking on "Statement" which appears in blue, like the other links do.

Source: www.investing in bonds.com. Courtesy of SIFMA.

If you want to check out a specific offering, it's most helpful to put in the CUSIP at the bottom of the screen under bond history. When you enter the CUSIP, the name of the bond will appear, and you can click on the number of trades in the right corner and see a complete trading history for that particular bond. This screen will tell you the trade date and time, price, yield, amount traded, and the type of trade. This site conveys much more information than you'll find about corporate bonds. The information in Figure 10.4 shows trade data for one bond issue. Like most munis, this bond trades infrequently. There was one sale to a customer in May and no other trades until August. On August 25, there were two interdealer trades (trades between dealers) and one dealer purchase from a customer. (Yields are not shown for interdealer trades.) About two weeks later, there was a sale to a customer. Assuming that one of these represented dealers sold the ten bonds, there was about a 2 percent spread between the dealer's purchase and sale prices. When the trades are current, it gives you an idea of what might be a reasonable price and yield if the market has not moved dramatically.

Source: www.investing in bonds.com. Courtesy of SIFMA.

Who is the insurer? What is the underlying rating?

Is there any negative information about the bonds I should consider?

If the bonds are premium bonds, what is the yield-to-worst?

If the bonds are discount bonds, what is the after-tax yield?

If the issue is outside your home state, what is the after-tax yield?

Are these bonds subject to the AMT?

Chapter Notes

[49] Matthew Posner, "Households Keep Muni Holdings Lead With Hedge Funds' Help," The Bond Buyer online, December 13, 2006.

[50] Jacob Fine, "Achtung, Munis: Fitch Ratings," The Bond Buyer online, October 14, 2003.

[51] Virginia Munger Kahn, "Good Times Keep Rolling for Municipal Bonds," New York Times, October 8, 2006, BU 28.

[52] David T. Litvack and Mike McDermott, "Municipal Default Risk Revisited," FitchRatings.com, June 23, 2003, 1.

[53] Naomi Richman and Bart Ossterveld, Moody's Public Finance Credit Committee, "Mapping of Moody's U.S. Municipal Bond Rating Scale to Moody's Corporate Rating Scale and Assignment of Corporate Equivalent Ratings to Municipal Obligations," Moody's Investors Service, June 2006, 4.

[54] Ibid., 2.

[55] Ryan McKaig, "Desperation Rears Head in New York," The Bond Buyer, October 12, 2001, 1, 39.

[56] "Moody's Downgrades JFK Terminal Debt," The Bond Buyer, October 8, 2001, 37.

[57] Jackie Cohen, "California Water District Downgraded after Declaring Bankruptcy," The Bond Buyer online, September 1, 2006.

[58] Lynn Hume, "Panelists Warn of 'OPEB Tsunami,' Urge Early Liability Disclosure." The Bond Buyer online, July 1, 2006. OPEB stands for other postemployee benefits.

[59] Colleen Woodell and James Weimken, "U.S. Rating Transitions and Defaults, 1986–2006," 3. Retrieved from www.standardandpoors.com/ratingsdirect.

[60] Ibid., 3.

[61] Jacob Fine, "Munis Hold Their Ground," The Bond Buyer Online, September 1, 2006.

[62] Shelly Sigo, "Florida Issuer Details Cash-Flow Trouble of $158m Deal," Thomson Financial, December 14, 2001. Retrieved from www.TM3.com.

[63] Fine., Note 13.

[64] Litvack and McDermott, 8.

[65] Richman and Ossterveld, 4.

[66] Robert Lamb and Stephen P. Rappaport, Municipal Bonds (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1987), 85.

[67] Lynn Hume, "NFMA Releases Final GO Disclosure Guidelines for Issuers," The Bond Buyer online, December 7, 2001.

[68] Philip Day and S. Jayasankaran, "Learning Islamic Finance," Wall Street Journal, March 12, 2003, C5.

[69] "Rating Guidelines for Texas Municipal Utility Districts," Fitch Research, August 21, 1997, 1.

[70] Elizabeth Genco, Program Support Manager, National Association of Charter School Authorizers, e-mail, January 10, 2007.

[71] David G. Hitchcock, "Public Finance Criteria: Charter Schools," Standard & Poor's, November 13, 2002, 2.

[72] Moody's U.S. Municipal Bond Rating Scale, November 2002, 5.

[73] Elizabeth Albanese, "Fitch Calls Its Charter School Ratings More 'Attentive' Than Others," The Bond Buyer, May 31, 2001, 3.

[74] No Author, "N.Y.C. Ballpark PILOTs Look, Act Like Taxes," The Bond Buyer online, August 7, 2006.

[75] Ibid.

[76] Joe Mysak, "Hotels Now Part of Convention Center Space Race," Bloomberg.com, April 13, 2005.

[77] Ibid.

[78] Rochelle Williams, "Looking beyond Gambling: California Tribes Get Boost from Judge's Ruling," The Bond Buyer online, August 2, 2002.

[79] Christine Albano, "Fitch: Despite Challenges, Prognosis for CCRCs Looks Positive," The Bond Buyer online, March 29, 2006.

[80] Helen Chang, "Heavy Health Care Exposure Means Rating Risk, S&P Says," The Bond Buyer online, February 4, 2005.

[81] Matthew Vodum, "Report: For High-Premium Single Family Revenue Bonds, Now Is the Time to Buy," The Bond Buyer online, August 22, 2005.

[82] Lamb and Rappaport, 91.

[83] Elizabeth Albanese, "Arkansas to Sell $60 Million Tobacco Deal Next Week," The Bond Buyer, August 30, 2001, 4.

[84] Humberto Sanchez, "Public-Private Deals Testing Traditional Credit Issues, S&P Says," The Bond Buyer online, April 8, 2005.

[85] Ibid.

[86] Humberto Sanchez, "Corporate Road Warriors on the Move," The Bond Buyer online, June 19, 2006.

[87] Tedra DeSue, "Georgia Eyes $4.5B of Debt for Highways," The Bond Buyer online, April 4, 2004.

[88] Yvette Shields, "Judge Rules in United's Favor in O'Hare Case," The Bond Buyer online, July 26, 2006.

[89] Yvette Shields, "Delta, Trustee Continue to Negotiate Dropping Leases," The Bond Buyer online, January 12, 2007.

[90] Rich Saskal, "Toll Road Public-Private Partnerships Could Be Good Play for Muni Investors," The Bond Buyer online, May 8, 2006.

[91] Joe Mysak, "Experts Aren't Paid to Write Infeasibility Studies," Bloomberg News online, May 23, 2002.

[92] Moody's Public Finance Credit Committee, 3.

[93] Standard & Poor's, "U.S. Rating Transitions and Defaults, 1986–2006," 3.

[94] Richard Williamson, "Investors, Analysts Warm to a Texas Specialty: MUD Bonds," The Bond Buyer online, May 31, 2004.