LET'S GET DOWN TO the nitty-gritty: making money from bonds. In this chapter, we review a variety of techniques and strategies that will help you determine when to buy and sell bonds, how to take advantage of tax benefits, how to minimize the risks to your capital, and how to increase your returns. In short, we'll offer practical and profitable ways to use all the previous information presented in this book.

There are two types of bond buyers: those who engage in a buyand-hold strategy and those who try to time the market. We view the former as investors and the latter as speculators. Those in the first group buy bonds and, in the absence of personal financial or strategic reasons to sell, hold them until they come due. The market timers in the second group, however, seek to anticipate interest-rate movements and then capitalize on short-term market swings by a strategy of in-and-out trading.

There is little evidence that even the top economists can consistently predict the health of next year's economy much less the direction of interest rates. If the world of finance has yet to produce a professional who can accurately and consistently predict the future, what is the likelihood that you or your broker can? Even if, through sheer random luck, you properly guess the direction of interest rates, you still might not make money unless you overcome the dual costs of trading spreads and taxes on the gain.

We endorse a buy-and-hold strategy because you only need to make one right decision: when to buy. The variations in a bond's price while you hold it are not a serious concern because you will be paid both your scheduled interest and the face value of the bond at its due date. Therefore, unless you hold long-term bonds, the ups and downs of a bond's price should not matter to you if you can hold the bond until it comes due at face value. When you trade bonds, however, you must make two right decisions to be successful: when to buy and when to sell. We recommend to our clients that they avoid market timing and leave this activity to traders who move big positions and watch the trading action all day every day. Making one right decision of this nature is hard enough; making two is a risky choice.

There are certain times when it may be financially necessary or strategically advantageous for you to buy or sell bonds. Although it's not easy to spot buying opportunities in the bond market, there is a tool, known as the yield curve, that's widely used to discover such opportunities. The yield curve can also help you decide which specific maturities, among the many alternatives available in the market, make sense for you to buy.

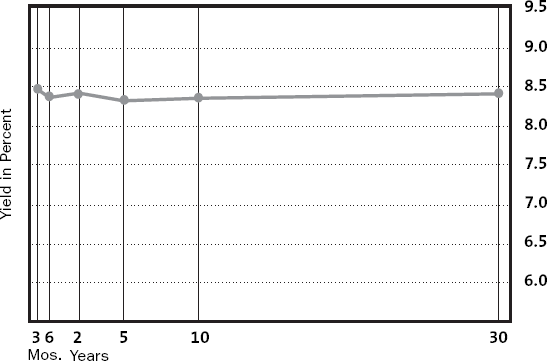

A yield curve is the name given to a chart that plots the interest rates being paid by bonds of the same credit quality but different maturities. In the chart, the interest rate is found on the vertical axis and the maturity on the horizontal axis. Short-term rates are controlled by the Federal Reserve (the Fed) by changing the federal funds rate, the rate at which banks borrow and lend to each other. That, in turn, affects the rates banks pay depositors and charge for loans. These rates affect all short-term rates, which, in turn, affect economic activity and inflation. Investors' expectations control long-term rates. The yield curve is a graphic description of borrowers' and lenders' actions in response to the changes in the costs of doing business.

Experts invariably disagree on which way interest rates will go next or on what the shape of the yield curve means for interest rates in the future. Although this is disappointing, you will still get significant information from studying the yield curve because it can tell you when to be careful and when an advantage may appear. The yield curve will help you decide how to maximize your return within the context of your own personal investment plan.

The yield curve has three classic shapes: ascending, flat, and inverted. Each, as depicted in the examples that follow, tells a different story.

Ascending yield curve. In a tranquil world, all yield curves would look like the one that appears in Figure 19.1. Bonds with the shortest maturities (those on the bottom left) would have the lowest yield (also on the bottom left) because there is less risk associated with holding them. For bonds that won't mature for many years, there is more uncertainty and additional risk. It's not unusual for there to be an ascending yield curve for, say, the first ten years of the period plotted on the curve and then a flatter curve from year ten to year thirty.

The greater risk of long-term bonds comes from their greater volatility, inflation risk, and default risk. Bondholders who take on that extra risk are paid back in the form of higher interest rates. The additional return on longer-term bonds is called the risk premium and is shown in the upper-right part of Figure 19.1. A spread of about 3 percent between the 3-month Treasury bill and the 30-year Treasury bond would not be unusual in an ascending yield curve. At times when the yield curve is ascending, consider buying longer-term bonds to capture the additional yield while staying within the parameters of your bond ladder, which is discussed later in this chapter under "Strategies for Reducing Market Risk."

Flat yield curve. When the yield curve is flat, you receive more or less the same interest rate whether you buy a short-, intermediate-, or long-term bond (see Figure 19.2). At these times, we generally advise our clients, within the context of their financial plan, to stay in the intermediate range because of greater market uncertainty about long-term bonds and the possibility of declining short-term rates. In that case, it usually makes sense to buy bonds with maturities only as far out on the yield curve as is comfortable until it flattens. This is called the "peak" of the yield curve. For the longer-term bonds, with maturities after that point, you may not be paid enough for the risk.

Inverted yield curve. If there is an inverted yield curve, bonds with a short maturity have a higher yield than long-term bonds (see Figure 19.3). An inverted yield curve is infrequent and sometimes indicates that a significant economic change is coming, such as a recession. In 2006, many pundits argued that the inverted curve did not indicate a recession because the demand of foreign buyers and hedge funds exceeded the supply of bonds, thus, driving long-term interest rates down.

Bond-buying decisions are more difficult under these conditions. If you buy longer-term bonds, you're not being paid for the risk. You can get the highest yield by taking what appears to be the safest path, buying short-term bonds. However, this strategy might have an unfortunate outcome because the inverted yield curve does not usually last for long. Short-term yields may rapidly decline, leaving you averaging down to ever-lower yields. You also miss the opportunity to lock in the yields available in longer maturities, which may look very appealing in hindsight.

The threat that you will have to average down (get a lower interest rate) when your bonds come due is what's called reinvestment risk. In the early 1980s, for example, all interest rates were sky high and the yield curve was steeply inverted. During this period, many very conservative CD buyers bought six-month CDs and kept rolling them over every six months as they came due at lower and lower rates as the years went by. Unfortunately for them, they missed a huge buying opportunity to lock in long-term Treasury bonds yielding 15 percent in the early 1980s. In the early 2000s, the yield curve flattened and then inverted with the same result: high short-term CD rates attracted the individual investor, while professional investors scrambled to lock in longer-term rates in anticipation of the decline in rates overall.

For an excellent presentation and discussion of the yield curve, visit SmartMoney's Web site at www.smartmoney.com. Follow the path to "Economy and Bonds" and then to "The Living Yield Curve" found in the Bond Toolbox area. There, you can see for yourself how the yield curve has changed from 1978 to the present.

We do not recommend market timing, but there are many times when it's appropriate to restructure your bond portfolio and sell bonds before they come due. Using the following strategies should help you decide when to take action.

Monitor the changes that may occur in your federal tax bracket. A substantial increase or decrease in your federal income tax bracket might lead you to a decision to sell municipal bonds and purchase taxable bonds, or vice versa. For example, your federal tax bracket might decrease as a result of your retirement, large business losses, substantial charitable contributions, or other deductions, or increase due to a big promotion, a great business opportunity, or an inheritance.

Check state tax rates if you move from one state to another. A change in your residence from one high-tax state to another high-tax state or from a low-tax state to a high-tax state can trigger a need for portfolio change to minimize your taxes. In each of these cases, you might sell the municipal bonds issued by one state and buy municipal bonds issued by the other state. For example, if you move from New York to California, you might want to sell your New York municipal bonds and buy California municipal bonds to take advantage of the California state tax exemption for in-state bonds. California would tax your New York municipal bond interest.

Follow changes in the federal tax code. Some tax-free municipal bonds, for example, are subject to the AMT. They're called AMT bonds. Discussion continues in Congress about modifying or abolishing the AMT; any tinkering with it could affect the desirability of owning or selling AMT bonds.

Profit from price gains. Consider selling if you have a substantial gain on your bonds and you have a noninvestment use for the money or wish to invest in another asset class.

When the general level of interest rates moves up or down, most bond sectors (for example, long-term bonds) usually follow. However, a bond sector may become relatively cheap compared to others as a result of the supply and demand for that sector.

Study the Treasury bond yield curve. Determine the most desirable maturity range based on your needs. Suppose you were considering the purchase of a bond with a five-year maturity. You might find that purchasing a bond in a longer or shorter maturity might provide a better return as well as support your particular situation. Also, compare the yields on outstanding Treasury bills, notes, and bonds in the same maturity. The off-the-run securities might yield a little extra because there is less demand for them. Maybe you wanted to purchase a longer-term bond. The large projected federal government surplus and the government buyback of 30-year Treasuries in the 1990s resulted in a sharp decrease in the yield of long-term Treasuries in 2000. However, when the projected surplus significantly diminished in 2001, the yield increased because the potential supply of Treasuries going forward seemed ready to increase.

Compare the Treasury yields to tax-exempt municipal bond yields. Even if you're in a lower tax bracket, municipal bonds might make sense for you if their yields approach those of Treasuries. There's a lot of historical data supporting the premise that on average the yields on highly rated, tax-free municipal bonds are normally 80 percent to 90 percent of Treasury bonds for similarly dated maturities. If yields on tax-free municipal bonds are greater than 90 percent of Treasuries, as they were for a time in 2000 and 2003, the municipals would be a good buy because they yield almost as much as Treasuries, and the income is tax free. In this situation, even the taxpayers in the lowest tax bracket benefit from munis.

When buying corporate bonds, compare the returns of subsectors in the same maturities. All corporate bonds do not move in unison. By comparing the yields of automobile companies to rail companies, for example, you will understand that there is a yield differential for similarly rated bonds in different market sectors. Junk bonds became relatively cheap in 1989, 1990, and 2001 because of the large number of defaults and the threat of more of the same caused by the recessions in those years. Thirty percent of the junk bonds defaulted in the early 1990s, although they became a buy after the yields had increased significantly and the threat of default had diminished. In 2007, junk bonds were very expensive; consequently, they should be avoided.

Consider investing in bonds that have had many rating downgrades but may appear promising to you because you believe there will be an upgrade. In 2006, for example, New York City bond ratings were upgraded, signaling that these bonds were becoming safer. This perception of safety was a consequence of New York's improved fiscal health, a credit rating upgrade, and investors' growing confidence in Mayor Michael Bloomberg. It helps if the bonds are insured, just in case your best guess turns out to be wrong.

Just as there are periodic bond-buying opportunities, there are also bond-avoidance situations, times when one or more sectors may be relatively expensive.

Compare the Treasury yield curve to the yield curve of other taxable market sectors. Professional bond traders always speak of the yield above Treasuries as a way to describe how a bond is priced. If you're not getting a satisfactory risk premium above the Treasury yield, don't take the risk. Buy the Treasury. The Treasury bond yield curve can be found on the Web at

www.bloomberg.com. See alsohttp://finance.yahoo.com/bondsfor interesting online displays that list the yields and spreads between maturities of Treasuries.Watch out for junk bonds. When the yield spread between Treasuries and junk bonds moves to within 200 basis points (2 percent), as it did in 2007, it's an indication that junk bonds are comparatively expensive.

Compare maturities. If the yield curve is relatively flat, there is little or no risk premium being offered for buying longer-term bonds. As a general rule, you want to be in short- or medium-term maturities if you are not getting enough interest to warrant longer-term bonds.

Compare asset classes among corporate bonds. Some sectors are often cheaper as a result of market news, but they may not have been repriced yet to reflect the increased risk. When a sector is being flailed by the media, prices drop substantially.

Ask questions about corporate bond yield spreads over Treasuries. The yield spreads indicate the market's perception of corporate strength, and they fluctuate based on rumor and market news. If a yield looks too good to be true, it probably is.

When interest rates go up, there is a hue and cry that bond investors will take serious losses. But we always love it when interest rates are rising because it creates wonderful opportunities for investing money at higher rates and increasing our income. For example, if interest rates go up from 4 percent to 6 percent per year over a period of time, an investor can increase cash flow by 50 percent. Remember, when the commentators say it is a bad time for bonds because rates are rising and prices are falling, you can say, let the bad times roll.

Quickly invest your cash. If you hold cash or cash equivalents, you can now invest the cash in intermediate-term bonds at a more favorable rate of return than when rates were lower. This can only be good news. Intermediate Treasury bond investments should be in the two- to ten-year range if the yield curve is fairly flat. Intermediate municipal bonds should be in the seven- to fifteen-year range if they have a steeper yield curve.

Consider cashing in your bank CDs. This strategy holds true only for a bank CD purchased from a bank and not for a CD purchased from a broker, a so-called brokered CD. (See chapter 12 for more on CDs.) If you hold a CD purchased directly from a bank, take advantage of the fact that the principal of the CD never goes down. If interest rates have risen significantly, you might cash in your bank CD, pay the penalty, and then reinvest your cash in a higher-yielding and equally safe investment, such as an intermediate-term Treasury, agency bond, or even another 5-year CD. To discourage this strategy, some banks charge one year's interest or more. The penalty might be higher than the interest that you earned and, thus, will reduce your principal. Other banks charge between a three-month and six-month interest penalty. Check with your bank on the withdrawal penalties before you invest. On the other hand, if interest rates are low, you can use bank CDs as a place to keep your principal safe until rates move up.

Cash in U.S. savings bonds that have been held for twelve months or more. If you hold EE or I savings bonds, you can cash them in after you hold them for twelve months or more. If you hold them for less than five years, you will pay a penalty equal to three months' interest, but if you hold them for more than five years, there is no penalty. The key point here is that you never lose any of the amount you invested or the accrued interest with a savings bond (except possibly the three-month interest penalty). If interest rates have risen significantly, you can cash in your savings bonds and earn even more income by reinvesting in safe but higher-yielding bonds. Keep in mind that if you cash in your EE or I bonds, you must pay federal income tax on the accrued interest.

Buy premium bonds. If you might sell bonds before maturity, premium bonds will hold their value longer in a rising interest-rate market. But keep in mind that if you spend all your interest income, you will be spending some of your principal as well.

Buy new issues. When rates are rising, you might consider buying new issues because new issues are price leaders. The brokers are hoping they will not have to take a loss on their existing inventory and do not mark down their prices quickly. New issues are priced at the current market value.

Hold on to inflation-protected bonds. Inflation-protected bonds such as TIPS and I savings bonds are a good hedge if interest rates are rising as a result of inflation. In that case, the principal of your TIPS and I savings bonds will increase in value if you hold them until their due date.

Swap your bonds. There are many opportunities to swap your bonds, although it's better to sell twenty-five bonds or more to get a better price. Three kinds of swaps are suggested:

Swap short-term bonds for intermediate- or long-term bonds. A swap will allow you to lock in higher returns if longer-term bonds are yielding significantly more than short-term bonds. In this case, you may either take a gain or sell at a small loss. While selling at a loss might not initially seem like a great idea, keep in mind that your loss will be small if the bonds that you are selling will come due within two years, because in this case they should be priced close to their face value.

Do a tax swap and take a tax loss. This is a trading strategy that one-ups the tax collector. It involves selling any low-interest coupon bonds you own that are selling below their purchase price. This generates a tax loss. Simultaneously, you buy new bonds to lock in the same or a higher return. In the 1970s, when interest rates were constantly rising, tax swaps were considered every year. The last quarter of the year was called the tax-swapping season.

Upgrade your credit quality. Swaps can be done to upgrade the credit quality of your portfolio by swapping a weaker credit for a stronger one at a time when the spread between better credits and weaker credits has narrowed.

Again, we love it when interest rates are rising. However, there is also money to be made when rates are falling as long as you think strategically. Here are some suggestions:

Don't stay in cash. When interest rates are low, you may believe that it will be best to keep your money in a low-yielding money market fund and wait for interest rates to rise. Although this strategy may work out well, many other times staying in cash may prove costly because the longer you wait for rates to go up, the higher the rates must go to compensate you for waiting and earning lower returns. For example, if money market rates are 2 percent and 5-year bond rates are 4 percent, if rates stay the same, you have lost 2 percent per year for the period involved. Even if rates do move up later, they must move up enough not only to make up for the lost interest but also to make up for the risk that the rates may not rise. Staying in cash is a type of market timing and is unlikely to work out favorably over the long term.

Buy EE bonds. EE savings bonds allow you to lock in the current return being paid by the Treasury for at least twenty years without losing any principal or accrued interest. If interest rates kick up in the future, you can redeem your EE bonds, take your gain, and then buy higher-yielding bonds.

Take a capital gain. When interest rates are low or falling, consider selling some of your bonds to take a capital gain. However, this strategy makes sense only if you intend to invest the proceeds in another asset class, such as equities or real estate, or have a need for cash for a personal expenditure, such as buying or improving your home. There is little or no advantage in taking a capital gain and then investing in similar bonds once you pay transaction costs related to selling and buying and taxes on the gain.

Consider the secondary market. Investigate the secondary bond market for previously owned bonds. When interest rates are falling, you might consider buying bonds in the secondary market rather than new issues. New issues, being price leaders, may have lower yields at these times.

Consider constructing a barbell portfolio. When interest rates are low, investors flock to intermediate-term bonds, pushing the yields of these bonds down. In this situation, you might increase the yield of your bond portfolio by using a barbell structure (see Figure 19.6). In this structure, you split your portfolio between long- and short-term bonds (each constituting one part of the barbell). In doing so, you capture the higher returns of 20− to 30-year long-term bonds and their gains if interest rates decline, while having ready access to the cash in short-term bonds that have maturities of two years or less. The combination of long-term and short-term bonds provides an intermediate-term average maturity and portfolio duration, which may be higher than the return on the intermediate-term bonds.

If you're a trader, a barbell will provide gains if long-term yields decline and you can sell your long-term bonds at a gain. If the long-term interest rates go up, the substantial short-term bond position would cushion the decline in the value of your portfolio. However, keep in mind that if you guess wrong, you may take substantial losses.

Buy bond funds with longer-term maturities. When interest rates are falling, longer-term bond funds will give you the highest total return. If you're adventurous, consider target maturity funds and long-term corporate bond funds. If you're more conservative, consider long-term Treasury or municipal bond funds.

Always view purchases of bonds and other investments in terms of their after-tax returns. To do so, you must first determine your highest federal income tax bracket. You then compare the return you would get on an investment that's taxable with the return on one that's not. The result is called the taxable equivalent yield. The following simple formula makes this comparison:

For example, assume that the taxable bond rate is 7 percent and your top federal income tax bracket is 28 percent. The computation would be made as follows: .07 × (1 - .28) = (.07 × 0.72) = .0504 or 5.04 percent. In this example, a taxable yield of 7 percent is equivalent to a tax-free yield of 5.04 percent if you're in the 28 percent federal marginal tax bracket. Thus, if you can get more than 5.04 percent on a tax-free bond, the tax-free bond would give you a higher after-tax return than a 7 percent taxable bond. This computation doesn't take into account state income taxes. The bond calculator at www.investinginbonds.com does take state taxes into account.

This is as good a place as any to review the tax implications of the bond investments discussed in this book. Keep these distinctions in mind when you compare yields and risks and decide on your asset mix.

Income exempt from federal income tax. Interest from tax-exempt municipal bonds and dividends from tax-exempt municipal bond funds, but not interest from taxable municipal bonds and taxable municipal bond funds. For some taxpayers, interest from AMT municipal bonds are subject to the AMT.

income exempt from state income tax but not federal income tax. Interest from Treasury bonds, notes, bills, STRIPS, TIPS, savings bonds, and certain agency bonds as well as dividends from certain taxable municipal bonds and bond funds that hold these securities.

Income deferred from current federal and state income tax but ultimately subject to tax. Interest from EE and I savings bonds until you redeem them. Even when you redeem them, they are not subject to state income tax. In addition, interest from EE and I savings bonds may be tax-free if used for education expenses by qualifying taxpayers (see chapter 7). Fixed deferred annuities are tax deferred until payout begins and then fully taxable. All interest from any bonds in a tax-sheltered retirement account is tax deferred until it is distributed and then the income is subject to federal income tax at ordinary income tax rates no matter what the source of the interest income. State taxation of these distributions varies from state to state.

Income subject to federal income tax immediately. Unless in a tax-sheltered retirement account, income from all taxable zero-coupon bonds, taxable municipal bonds, and AMT bond income for some taxpayers.

One subject often raised by our clients is how to place bonds in their accounts to minimize taxes most effectively. Which bonds should be placed in a taxable account and which should be placed in a tax-sheltered retirement account, such as an IRA or 401(k)? Although the answers are not black and white, here are some suggestions that may help.

Always place all tax-exempt municipal bonds in taxable accounts. These bonds should never be placed in tax-sheltered retirement accounts (unless the yield on tax-exempt municipal bonds is higher than taxable bonds) because distributions from these accounts are always treated as ordinary income for federal income tax purposes even if they result from tax-exempt municipal bonds.

Place EE and I savings bonds in taxable accounts. The tax deferral is wasted in a tax-sheltered retirement account, even assuming you can get a trustee to hold them.

Hold taxable STRIPS and TIPS in tax-sheltered retirement accounts. Some of the interest from these securities results in imputed or phantom income that is currently subject to tax if held in taxable accounts but creates no current tax liability if the securities are held in tax-sheltered retirement accounts.

If you place taxable bonds and bond funds in tax-sheltered retirement accounts, the advantage is that the taxable interest and capital gains are deferred and not subject to current tax. The disadvantage is that long-term capital gains generated in these accounts are treated as ordinary income when they are distributed. Thus, if a bond is held for more than one year, you have converted long-term capital gains, which are lightly taxed, into ordinary income, which may be heavily taxed. In addition, there is no tax benefit for losses realized in a tax-sheltered retirement account. Note that there is a 10 percent tax penalty on an early withdrawal before age 59½ from a tax-sheltered retirement account.

If you place bonds that are infrequently traded in taxable accounts, any long-term capital gains are lightly taxed in 2007 at a 15 percent federal income tax rate.

Tax-exempt municipal bonds are the best and last great tax shelter for individual investors. Individuals who are in high tax brackets benefit most from an investment in tax-exempt municipal bonds. However, even taxpayers in the 25 percent tax bracket generally can benefit from an investment in these bonds because the interest income is not subject to federal income tax. In 2007, a single taxpayer reached the 25 percent federal income tax bracket when the taxpayer's taxable income exceeded $31,850; married taxpayers reached the 25 percent federal tax bracket when their taxable income exceeded $63,700.

However, there are two other categories of municipal bonds to watch out for: one category is municipal bonds subject to the AMT. They're called AMT bonds because their interest income is subject to the federal AMT for certain individuals. The AMT keeps changing, and it is unclear who will be hit by this tax in any year.

The other bond category is called taxable municipal bonds. The interest income from these bonds is subject to federal income tax but not subject to the AMT. Taxable municipal bonds provide a higher interest rate than tax-exempt municipal bonds, and many are insured; some are zero-coupon bonds. Highly rated taxable municipal bonds are excellent investments for your tax-sheltered retirement accounts.

Generally, bonds that are good for individuals in low tax brackets are also good for tax-sheltered retirement accounts because in both cases interest income is either not subject to tax currently or is taxed at a low rate. Some individuals in high tax brackets will be in a lower tax bracket after they retire from their full-time job and their earned income terminates along with their job. Should this be the case for you, review your bond portfolio carefully. You may be in a position to take advantage of your new lower tax bracket and increase your after-tax income.

For tax-sheltered retirement accounts and low-tax-bracket individuals:

Consider STRIPS, TIPS, Treasuries, agencies, taxable muni bonds, and highly rated corporate bonds. They are safe. The adverse tax consequences of STRIPS and TIPS (because they generate phantom income) will not result in a significant amount of tax if the low-bracket taxpayer has little or no other taxable income.

Check out AMT bonds. If it's clear that you will not be subject to the AMT currently or in the future, buying AMT bonds may be an opportunity for you. They often provide 20 to 30 basis points more yield than non-AMT bonds, frequently without any sacrifice of credit quality. However, keep in mind that AMT bonds may be difficult to sell at a good price. In addition, even if you are not subject to the AMT today, you might be subject to it in the future. Some muni funds may hold a high proportion of these bonds to boost their yield. Always investigate what percent of a bond fund is held in AMT bonds to maximize your return after tax. The fund company can give you this information.

Consider selling your tax-free municipal bonds. If you are no longer in a high-enough tax bracket to benefit from the tax exemption, you may do better on an after-tax basis by selling your municipal bonds and buying higher-yielding taxable securities including taxable municipal bonds and AMT bonds. This may also be the time to buy a fixed immediate annuity.

Redeem your EE and I savings bonds and buy safe plain-vanilla bonds, such as Treasury bonds, to generate current cash flow. However, the redemption will be a taxable event unless the income from such bonds can be used for educational purposes by qualifying taxpayers.

Buy TIPS and I savings bonds for safety and to provide protection against inflation.

Investors must walk the line between fear and greed. We want to have as much as we can and often feel envious when our peers are doing better with their investments than we are. The reality is that the return on an investment is generally proportional to the degree of its risk. Your peers, for the most part, have simply taken on more risk if their returns are better than yours or they have a selective memory of only the good times. There is no free lunch. However, there is this book, and the following information provides guidelines on how to reduce risk while still getting a good return.

If you've read this far, you've probably already assessed your need for income, the level of risk you're willing to assume with your bond investments, and your capacity to actually sustain losses. Now consider the following questions:

If your bond portfolio declined in value would you panic and sell your bonds? If so, you probably have a low risk tolerance and failed to keep in mind that your bonds will come due at their face value. To be at peace with your bond investments, you should consider buying only short- and intermediate-term bonds that you can hold until they come due. If you can hold bonds until they come due, you will have no reason to panic or sell your bonds prematurely.

Would you engage in an interest-rate play by buying 30-year bonds with an eye toward selling for a significant gain if interest rates decline? Would you buy a bond with a 12 percent yield and take the risk of losing a significant amount of your capital? If so, you are a speculator and should have a high capacity for loss.

Is your portfolio heavily weighted in equities and illiquid investments such as real estate? If so, a conservative bond portfolio will provide a safe foundation enabling you to take on more risk with other investments and business ventures.

When bond investors think of risk, the main risk that many consider is default risk, the risk of an issuer going bankrupt and bondholders losing their investment. Bad times in an industry or problems that are specific to the issuer might cause a default. Here's how to stay away from such risk.

Buy the plain-vanilla bonds described in chapter 2, and in any case buy only bonds rated at least A or better for municipal bonds and AA or better for corporate bonds. When you're looking at ratings, it's important to determine when the bond was last rated by the rating agency. In general, ratings by the major rating agencies are often good predictors of the likelihood of a default. However, if the rating was done years ago, it may not reflect the current financial position of the issuer. Ask your broker not only for the rating of the bond, but also for the date the bond was last rated and by which rating agencies; then hope for the best because we all know that the rating agencies sometimes make big mistakes, as they did in rating Enron.

Purchase bonds that are insured by a highly rated insurer or have some other credit enhancement that you can understand. Bond insurers are only as good as their asset base and can get overextended. If a credit agency downgrades a bond insurer, all the bonds it insures will be downgraded as well. If you buy a portfolio of insured municipal bonds, vary your holdings so that different municipal insurance companies are represented, thereby providing diversity.

Diversification of bond issuers and due dates is a good way to minimize the risk to your bond portfolio. Diversify your holdings by issuer and, where applicable, by geographic region and market sector. If you don't have the minimum $50,000 we consider adequate to buy a sufficiently diversified bond portfolio, buy bond funds. There are many to choose from, including bond index funds, corporate and junk bond funds, and mortgage bond funds, including GNMA funds and municipal bond funds. Bond funds consisting of bonds issued by less-developed countries or denominated in a foreign currency are "high risk/high reward" investments. These bonds are exceptionally risky and could be subject to losses due to currency fluctuations as well as country defaults, as evidenced by the defaults in Russia and Argentina. However, keep in mind that even if your bond portfolio is less than $50,000, diversification is not required if you buy only plain-vanilla bonds, such as Treasuries, agencies, savings bonds, or similarly rated bonds, as described in chapter 2.

Consider including different geographic regions in your municipal bond portfolio, even if you are in a high-tax state. Although you may pay some extra taxes, this practice protects you from the economic impact of regional downturns, particularly if you hold some lower-rated muni bonds. However, diversification may not be required if you buy insured muni bonds that are insured by different highly rated insurance companies.

Diversify your corporate holdings by purchasing bonds from different market sectors. In this way, you can obtain the higher yield offered on corporate bonds while protecting yourself from the impact of an economic decline affecting one sector. One corporate bond fund would provide you with enough diversity.

Purchase plain-vanilla bonds that are simple to describe and understand. Although stories about stocks might help you to find an undervalued stock, stories about bonds are usually bad news. If the features of the bond are complex, remember that they were constructed for the issuer's benefit, not yours. Simple is good.

Think twice about an investment in a sector, market, or region that is getting bad press. Take some time to consider if the extra yield is worth the extra risk. You should spend more time picking out a bond than a shirt. Purchase bonds in thriving areas and growing sectors of the economy.

In bad times, not only do interest rates often go down, but also the spread between the interest rates payable by solid issuers and weak issuers widens to reflect the higher chance of default of the weak issuers. The opposite happens in good times when the spread between solid issuers and weak issuers lessens, and you are not paid for the risk you take by buying the weaker issues.

When spreads lessen across the rating spectrum, buy the good credits. Don't reach for extra yield in good times, when you're not being paid enough to take the risk. Even when spreads widen out between low- and high-grade credits, purchase only weak credits if you feel confident in your judgment. If not, keep your assets in higher-rated bonds.

Buy prerefunded munis. They are the safest financial instruments in the municipal bond area because they're backed by assets placed into an escrow account. Ask what the prerefunded assets are, especially if the bonds have not been rerated. The best case is when the munis are prerefunded with Treasuries.

Purchase Treasuries and agencies instead of corporates. You don't need to diversify when you purchase Treasuries so a Treasury fund is overkill unless you want the check-writing privileges. Some agency funds may contain leverage and derivatives and may not be as safe as you think. Pure GNMA funds are safe and worthy of your consideration.

With the exception of money market funds, CDs, and savings bonds, all bonds are subject to market risk, whether they are Treasury bonds or junk bonds. The principal cause of a price decline caused by market risk is generally a rise in interest rates. There are steps you can take to protect yourself against this risk.

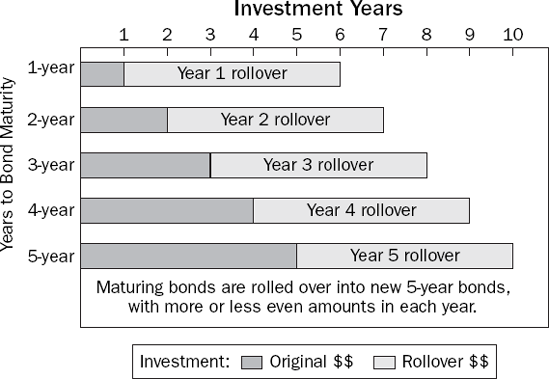

Use a bond ladder to reduce market risk and reinvestment risk. A bond ladder is a powerful risk-reduction technique that will smooth out the interest rate you earn and thus reduce reinvestment risk. Laddering a portfolio means you buy and hold a number of bonds that will come due over a period of years. The period might range from five to twenty years. When the first bond comes due, it's replaced with a bond of an equal amount at the longer end of the maturity ladder. For example, if you want to invest $100,000 in a bond ladder over a five-year period, you would buy $20,000 of bonds coming due in each year (see Figure 19.4). When the first $20,000 bond came due, you would buy another 5-year $20,000 bond, thus, extending your ladder by one year.

The bond ladder is a flexible tool that takes into account both the structure of the yield curve and your own particular needs. If the yield curve is flat, you might want to keep your ladder from one to ten years. If the yield curve is ascending and steep, you might prefer a five to twenty-year ladder. If you have a particular expense, such as college tuition, you can modify your ladder to target particular years so that the required tuition money would be available for each year. This is called "income matching."

A laddered portfolio has several advantages. It averages the rates of interest that you earn over a period of years. A ladder provides more overall return in a rising interest rate market because if interest rates are rising, you will replace lower-yielding bonds that come due with higher-yielding longer-term bonds. A ladder results in less market risk than investing only in longer-term bonds. It provides flexibility by giving you access to your funds, because some bonds will come due each year or so, without the cost of selling a longer-term bond. It allows you to buy some longer-term bonds without undue market risk. Laddering is a strategy for individual investors who know that they can't predict where interest rates may go. It produces a steady, predictable stream of interest income that pays more than a strategy based on short-term investments only and reduces interest-rate risk and reinvestment risk.

When constructing a ladder, take into account all your investments in all your accounts, including money market funds, bank CDs, and savings bonds. Don't make the mistake of having a separate ladder in your taxable account and another similar ladder in your tax-sheltered retirement account. You should plan on one ladder that reflects all your accounts, while keeping in mind your cash flow needs. Once you have your ladder, don't worry about the current value of your bonds in good or bad times, unless you're looking for signs of quality deterioration. Unless you're going to sell, market fluctuations don't matter if you can hold your bonds until their due dates. In a so-called bear market for bonds (when interest rates are going up and the price of bonds is going down), you can reinvest at higher rates. In a bull market (when the price of bonds is going up), you can take capital gains.

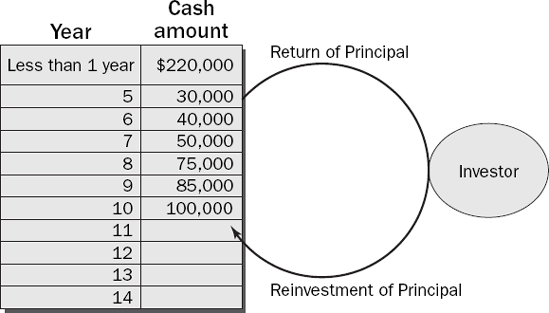

We take laddering one step further and recommend that clients use a custom bond ladder so that bonds are purchased to come due over a period of years, with the amounts of bonds coming due in different years set to match the amounts needed to meet the client's financial objectives and needs. Figure 19.5 is an example of a custom bond ladder we designed for Peter, whom you met in chapter 3. The ladder has $220,000 in money market funds and Treasury bills all coming due in less than one year so that Peter has access to enough cash to start up his new business. Because Peter is rewarded by higher interest rates for each year in the ladder, he decided to put increasing amounts into those later years. He plans to reinvest the cash available when a bond comes due or when his new business turns profitable. To whatever extent they don't need their annual interest income for Peter's new business or to support their family, Peter and Jane plan to reinvest it in another bond so that their portfolio will grow.

A custom bond ladder can be modified over the years as your needs and family situation change and as the returns on short-term and long-term bonds change. For example, at some point, there may be very high short-term rates and long-term interest rates. If you were financially flexible enough, you might modify your ladder to invest only in short-term and long-term bonds, with nothing in between. Instead of a ladder, you might construct what is called a "barbell," as shown in Figure 19.6.

A barbell may be visualized as a ladder with a few or many rungs missing in the middle. The barbell strategy is often used by traders because the short and long bonds are the most volatile, and the market swings will produce the greatest possibilities for gains and losses.

Once you become comfortable with the idea of a bond ladder, you should create a custom ladder to suit your particular needs, taking into account the investment climate in which you find yourself. Your decisions about how to structure your ladder should blend your personal needs and where the yield curve indicates you can get the highest yield.

In summary, a well constructed bond ladder will often produce a portfolio with returns close to the return on long-term bonds, but with substantially less risk.

Purchase bonds that you can hold to their due date. If you buy short- and intermediate-term bonds, your market risk will be significantly reduced because it's more likely that you can hold them until they come due. If there is inflation and interest rates go up, that's good news because when your bond comes due, you can reinvest at a higher rate.

Buy individual bonds rather than bond funds. Remember that bond funds never come due. If interest rates go up and stay up for many years, which they have done in the past, you might have the equivalent of a permanent loss. Individual bonds come due at their face value. However, we do recommend bond funds for junk bonds and mortgage securities. If you wish to speculate with a portion of your portfolio, you might use bond funds to invest in foreign bonds, convertible bonds, and other off-the-beaten-path investments.

Liquidity risk is the risk that you may not be able to sell your bonds quickly at an attractive price if you can't hold them until they come due. Listed next are strategies on how to reduce the liquidity risk.

Buy bonds in minimum blocks of $25,000. If not, consider open-end bond funds for great liquidity.

Purchase bonds that will come due when you need the cash. This reduces transaction fees and provides security knowing the money will be there when you need it.

Select bonds with good credit ratings that have wide market appeal. Look for ratings from well-known issuers or bonds supported by insurance or other credit enhancements that are in stable market sectors, both regional and industrial. Highly rated bonds will sell more easily and at smaller spreads.

A call is not favorable to an investor because issuers generally call bonds when interest rates have declined. A call may result in rein-vestment risk because the money returned from a called bond may have to be reinvested at a lower interest rate. Here are ways to protect yourself from call risk:

Before you buy a bond, ask your broker for a statement of all calls, not just the fixed calls. Request a copy of the bond description from one of the information agencies, such as Bloomberg. They have a listing of all the calls.

Buy bonds that are not callable for at least five years. If bonds are callable in less than five years, you should get a higher interest rate than for noncallable bonds.

Buy low-coupon bonds. Low-coupon bonds are less likely to be called. However, low-coupon municipal bonds bought at a discount may result in adverse tax consequences. Check with your tax adviser before you buy bonds selling at a deep discount.

Request a listing of a fund's holdings. Before you buy a fund, request a complete listing of its holdings to see if they consist primarily of premium bonds. If they do and the bonds are called away, it will reduce the fund's NAV.

Bonds are all about generating income to satisfy your financial needs. In this section, we consider strategies you might use to satisfy short- and long-term goals and, finally, strategies we've developed over the years to generate additional income.

You may want to invest at least some money in short-term bonds to create a readily available source of funds that will take care of you if you lose your job or have some other emergency needs. See chapter 17 for suggestions on how to fund emergencies without buying cash equivalents.

You may want to save for other short-term goals, such as education expenses or the down payment on a house, car, or boat. The following strategies will help you accomplish these objectives.

Buy bonds that come due when you need the money. That way you can minimize the amount of money that you need to keep in short-term investments.

Buy Treasury bills, Treasury notes, STRIPS, and CDs. You can buy them to match your maturity needs. You would hold them until they come due or roll them over at maturity into other Treasuries. If you use TreasuryDirect to buy them, you pay no transaction costs.

Buy money market funds.

Use bank money market accounts for small sums of money. They provide limited checking privileges but yield more than a traditional checking account.

Use money market funds tied to your checking account. Most or all your cash will earn interest if the funds do.

Use a stand-alone money market mutual fund for excess shortterm funds if they yield more than funds tied to your checking account.

Use cash-management accounts for added yield and somewhat more risk. Invest with a strong sponsor for added safety. Whether interest rates go up or down while you're saving, your principal will be protected. However, distinguish between cash-management accounts, money market mutual funds, and tax-exempt money market accounts. (See chapter 15 for descriptions of each.)

Buy short-term bonds. Consider agency bonds, highly rated corporate bonds and corporate retail notes, and municipal bonds that all come due within five years. If you can hold them until they come due in five years or less, there would be no market risk and no loss of principal unless there is a default. These short-term bonds are also available in a variety of mutual funds. There are short-term corporate and muni bond funds. For the more adventurous, there are riskier funds, such as loan participation funds, municipal preferred stock, and ultrashort bond funds.

Check out the advantages of EE or I savings bonds. Although you can't cash them for twelve months, your principal is completely protected, and the interest earned is tax deferred until you cash them, subject to a three-month interest penalty if you redeem them within five years.

Buy callable bonds. If you can accept that they might be called, you may receive a higher yield-to-call and yield-to-maturity. Only purchase them if the calls and the maturity work with the rest of your portfolio. Do not overload your portfolio with bonds all maturing or callable in the same years.

Buy death put bonds if you are anticipating a death in your family. These are corporate retail notes and some certificates of deposit that you can sell back to the issuer if the bond owner dies. This will enable you to fund final expenses and estate taxes.

Sometimes your strategy will be to invest for the long term in order to create a fund for retirement and for significant family needs, such as paying for education expenses in ten to fifteen or more years. In this case, consider using the following kinds of bonds to accomplish these objectives.

Buy intermediate- or long-term Treasury bonds, STRIPS, and agency bonds for safety. These bonds are among the safest you can buy. The Treasuries and certain agency bonds are exempt from state income tax.

Buy certain federal mortgage securities through funds. Ginnie Mae funds provide safe investments that will not default.

Buy EE and I savings bonds to let your savings grow tax deferred. Savings bonds can be held for as long as thirty years without market risk or the risk of loss of any principal. EE and I savings bonds also provide a tax deferral, and if they can be used for education, a tax-exempt return for certain qualifying individuals.

Use I savings bonds and intermediate- or long-term TIPS as hedges against inflation.

Check out intermediate- and long-term highly rated corporates and highly rated municipal bonds. Corporates and taxable municipal bonds will provide a higher rate of return than Treasuries and agencies. However, tax-free municipal bonds may provide a higher return after taxes. If the highly rated corporate and municipal bonds are selected carefully, they should prove to be good investments for the long term. They can also be purchased through bond index funds, targeted maturity funds, and municipal bond funds.

Certain bonds and securities will enable you to increase the return from your bond portfolio if you are prepared to take on additional risk. Here are some suggestions:

Consider fixed immediate annuities. They might be good investments if used as income replacement for earned income when you retire (see chapter 12).

Buy highly rated taxable bonds. If you are retired and in a low enough tax bracket, consider selling your tax-free municipal bonds and buying higher-yielding corporate bonds and retail notes, corporate bond funds, and bond index funds. Keep in mind that highly rated corporate bonds are riskier than similarly rated muni bonds.

Buy junk bond funds. Consider junk bonds only for the speculative part of your portfolio and only if you can earn substantially more as compared to safer taxable bonds to compensate you for a great deal more risk. The amount of additional return will depend on how dicey the market is. Although you may buy them in good times, you need to be compensated for the losses you may experience in bad times. Remember that junk bonds trade more like stocks than bonds. Two well-regarded junk bond funds are Vanguard High-Yield Corporate, and Fidelity Capital & Income Fund. The Vanguard fund is conservative and as a consequence the yield is not as high as those of some other junk bond funds (see chapter 15).

Buy long-term bonds. Although we have cautioned against buying long-term bonds, they have their advantages. They generally yield more than shorter-term bonds, and they appreciate more in declining interest-rate markets. If a higher current return is important to you and you can afford to risk some of your principal, consider buying long-term bonds in the following situations:

There is a steep yield curve so that long-term bonds yield considerably more than short- and intermediate-term bonds, and you have more than a ten-year period during which you can hold these bonds.

Long-term bonds are yielding more than intermediate-term bonds, but you do not have a ten-year holding period. However, you're prepared to take a market risk because of the high current return and the possibility of a significant capital gain. In other words, you are knowingly speculating on the direction of interest rates.

Long-term bonds are yielding considerably more than intermediate-term bonds, and you have a substantial portfolio of bonds that are short term and intermediate term, so that you can hold the long-term bond forever as part of your permanent portfolio. In this case, adding long-term bonds to your bond ladder to get the extra yield is not a risky strategy, and we recommend it. You may also want to buy long-term bonds if you have a substantial portfolio and are concerned with reinvestment risk.

use premium bonds to get more current income. Why would you pay $1,200 for a bond that comes due at its face value of $1,000? As one investor said, "I didn't build my capital by paying premiums for anything!" The impression is that you're paying more than you should. This reluctance on the part of some investors may provide you with an opportunity to get the following possible benefits from premium bonds: a higher yield-to-maturity than a par or discount bond, a higher cash flow, and a cushion in the face of increasing interest rates.

use discount bonds and zero-coupon bonds to grow your port-folio. Consider buying discount bonds and zero-coupon bonds, such as Treasuries, STRIPS, and zero-coupon municipal bonds, if your income is high and you want them to serve as a savings-and-growth portfolio. Consider buying discount bonds in the following situations:

They are yielding more than par and premium bonds after taxes. Take into consideration that the discount may be subject to tax each year or when the bond comes due. Check with your tax adviser.

You're concerned that currently high interest rates will decline significantly in the future. In this case, the appreciation of the discount bond as it approaches its face value will help maintain the bond's yield-to-maturity. If you buy a zero-coupon bond, you will get the stated yield-to-maturity because there is no income from the bond that you need to reinvest. In addition, if interest rates do decline, discount bonds will appreciate in value more than par or premium bonds.

Because of its lower coupon, there is less chance of a discount bond being called than a par or a premium bond.

Reread this book. It's all here: descriptions of specific bonds, information on how to find a bond broker, details on many different funds, and numerous strategies on how to make and save money. Enjoy and profit from the efforts of our labors to make yourself wealthier and wiser.

If you have less than $25,000 to invest, buy short-term or intermediate-term bonds. Don't buy long-term bonds, because you can't afford the market risk if you need your funds. You might not need credit diversification, but you might need maturity diversification. How would you deal with that? Buy the following short- or intermediate-term bonds:

Treasury bonds

TIPS

Agency bonds

CDs

EE and I savings bonds

Highly rated muni bonds (if you are in a high tax bracket)