Chapter 4

What's My Greatest Performance Block?

This chapter

![]() revisits Gilbert's Behavior Engineering Model, and goes beyond it

revisits Gilbert's Behavior Engineering Model, and goes beyond it

![]() presents other models for improving human performance to help you view the performance world from a variety of perspectives—not just ours

presents other models for improving human performance to help you view the performance world from a variety of perspectives—not just ours

![]() guides you to apply other models to strengthen your professional skills

guides you to apply other models to strengthen your professional skills

![]() concludes with a “bottom line” for investigating performance blocks.

concludes with a “bottom line” for investigating performance blocks.

Tools in this chapter include

![]() three performance models you can apply to your work

three performance models you can apply to your work

![]() a job aid for identifying performance blocks.

a job aid for identifying performance blocks.

Sensitizing Your WLP Team, Management, and Clients to the World of Human Performance Improvement

Over the years we have found that the exercise we asked you to do in chapter 4 of Training Ain't Performance—the one titled “I would Perform Better If…” (pp. 37-41)—is one of the most effective ways to open people to the range of factors influencing workplace performance. It is a rapid means for discovering where the major performance blocks exist. To remind you, here are the basic steps in the exercise:

![]() First we asked if you could perform better than you are currently performing…even a little better. You answered “yes.” We know this because 100 percent of the thousands of people to whom we have posed this question answered “yes.”

First we asked if you could perform better than you are currently performing…even a little better. You answered “yes.” We know this because 100 percent of the thousands of people to whom we have posed this question answered “yes.”

![]() Then we asked, “What's holding you back?” or “Where's the block?” and we offered you six choices:

Then we asked, “What's holding you back?” or “Where's the block?” and we offered you six choices:

I would perform better if…

![]() 1. I knew the exact expectations of the job and had more specific job feedback and better access to information.

1. I knew the exact expectations of the job and had more specific job feedback and better access to information.

![]() 2. I had better tools and resources to work with.

2. I had better tools and resources to work with.

![]() 3. I had better financial and nonfinancial incentives/consequences for doing my job.

3. I had better financial and nonfinancial incentives/consequences for doing my job.

![]() 4. I received more and better training to do my job.

4. I received more and better training to do my job.

![]() 5. My personal characteristics and capacities better matched the job.

5. My personal characteristics and capacities better matched the job.

![]() 6. I cared more and wanted to do my job better.

6. I cared more and wanted to do my job better.

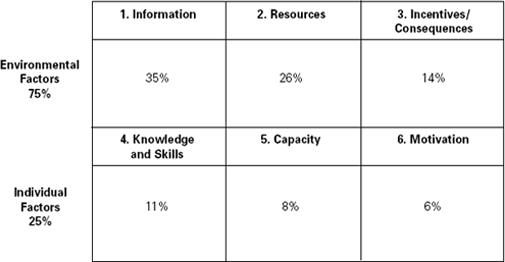

![]() Next we displayed Thomas Gilbert's Behavior Engineering Model (somewhat adapted) and showed how most people have responded to the choices. Each of the six choice numbers above corresponds to a key set of factors that affect workplace performance (see Figure 4-1).

Next we displayed Thomas Gilbert's Behavior Engineering Model (somewhat adapted) and showed how most people have responded to the choices. Each of the six choice numbers above corresponds to a key set of factors that affect workplace performance (see Figure 4-1).

Figure 4-1. Gilbert's Behavior Engineering Model (Adapted) with Data

Basically, the exercise and model combine to demonstrate that 75 percent of the factors affecting people's performance are found in the environment and only 25 percent reside within the individual. As we pointed out, despite the potential limits and biases of self-reporting, these figures truly reflect the real world of work. Yes, 70 to 80 percent of the factors that influence workplace performance are environmental—outside of the individual. To improve performance, then, let's begin with the environment.

An Activity for Your WLP Team

Review pages 37–44, almost all of chapter 4, in Training Ain't Performance, and then conduct the Gilbert exercise with your team. Give each person a small sticky note on which to write the number of her or his choice (only one choice per person). Collect these and show what the results look like on a flipchart sheet (as shown in Figure 4-2).

Figure 4-2. Example of the Results of a Workplace Learning and Performance Team's Responses

Debrief this exercise to highlight the following points (from Training Ain't Performance, p. 41):

![]() Lack of performance in the workplace is far more frequently caused by environmental factors than by individual ones.

Lack of performance in the workplace is far more frequently caused by environmental factors than by individual ones.

![]() Nevertheless, we continue trying to fix the individual rather than the environment.

Nevertheless, we continue trying to fix the individual rather than the environment.

![]() It is cheaper and easier to fix the environment.

It is cheaper and easier to fix the environment.

Ask if this has been your team members' observation in their own work. Would it really be easier to fix the environment? What would it take?

Use this exercise with client groups as well. It is a good opener to a discussion of why the default “training” solution for lack of performance seldom works as anticipated.

Beyond Gilbert's Model

Gilbert's Behavior Engineering Model is a wonderful aid to opening eyes and uncovering what affects workplace performance—pinpointing the blockages—so that people can begin to view performance more systemically. Other human performance leaders have provided us with different models for examining performance gaps. What follows are two interesting models to stimulate your thinking and practice. They are only representative of the many models that have been published, and we offer them here to expose you to a small sample of the rich variety of models available to help you deal with performance issues. In examining the ones we offer, you advance beyond Training Ain't Performance and strengthen your ability to help your organization attain its goals.

The PIP Model

An important name in human performance improvement (one you should use in conversation to demonstrate your knowledge of the field) is Joe Harless. As one of the pioneers in the field (and a former student of Gilbert), Harless developed his own strategy, which he labeled PIP(for performance improvement process). What triggered this model was the discovery he made in follow-up evaluations to training. He found that “despite the training having been well-designed in accordance with the standards…” (Dean and Ripley 1997, p. 94) and although learners performed well on tests, the skills and knowledge were not being transferred to the workplace. This prompted him to develop his PIP model, which incorporated a new process called front-end analysis. The model provided a foundation on which many later models have been built. Figure 4-3 presents an overview of the PIP model. Let's examine its steps and try to place it in a real-world context to help you determine how you can put it to use in your workplace.

Figure 4-3. PIP Model in Overview

![]() Plan and organize the performance improvement program. Let's say you have received a request to train or intervene in some way. Or, you or someone else has spotted gaps between what should be (or might be) and what currently is the performance level in your organization. The analysis you conducted using the organizational human performance system in chapter 3 would be an excellent means for uncovering the gaps—the lack of alignment between business goals, objectives, and performer accomplishments. Thus, you plan and organize your performance improvement program. You obtain time, resources, and permission to proceed; gather data; and establish success criteria and metrics.

Plan and organize the performance improvement program. Let's say you have received a request to train or intervene in some way. Or, you or someone else has spotted gaps between what should be (or might be) and what currently is the performance level in your organization. The analysis you conducted using the organizational human performance system in chapter 3 would be an excellent means for uncovering the gaps—the lack of alignment between business goals, objectives, and performer accomplishments. Thus, you plan and organize your performance improvement program. You obtain time, resources, and permission to proceed; gather data; and establish success criteria and metrics.

![]() Conduct organization alignment to identify improvement projects to be undertaken. Let us say you have uncovered five major gap areas. You cannot attack them all, so you have to prioritize your efforts to determine what you (or you and your team) can take on. In Training Ain't Performance(chapter 5, pp. 53-54), we pointed out that there are three dimensions to a performance gap:

Conduct organization alignment to identify improvement projects to be undertaken. Let us say you have uncovered five major gap areas. You cannot attack them all, so you have to prioritize your efforts to determine what you (or you and your team) can take on. In Training Ain't Performance(chapter 5, pp. 53-54), we pointed out that there are three dimensions to a performance gap:

1. Magnitude—how big and all-encompassing the gap is. Is the distance between desired and actual performance very wide? Is it prevalent organization-wide or simply local?

2. Value—how much the gap represents to the organization in terms of revenues, profits, or cost savings.

3. Urgency—how quickly it must be resolved. What are the consequences to the organization if it isn't handled?

Obviously, the greater these three factors, the higher the priority to close the gap. However, sometimes the organization has nonmonetary objectives. How might you deal with those?

Harless offers a simple way of making decisions through the traditional method called paired comparisons. Here's how it works:

1. Create a matrix with all the gaps labeled along the top and down the side, as in Figure 4-4.

2. Darken the cell that compares each gap to itself (for example Gap A with Gap A) and all of the cells below it, as in Figure 4-5. This leaves you with empty cells that permit every gap to be compared with every other gap.

3. Start with the first cell (that is, in Figure 4-5 the cell containing an arrow). Ask, “Between Gap A and Gap B, which has the greater impact on the organization's goals and objectives?” Include clients in the decisions. Argue. Discuss. Decide. You must make a choice. Continue to make a decision for each cell. At the end, the matrix should look similar to the one in Figure 4-6.

4. Count up the “scores” for each gap—the number of times a letter is listed as having greater impact. In the example shown in Figure 4-6, here are the scores:

| Gap A = 3 | Gap D = 2 |

| Gap B = 4 | Gap E = 0 |

| Gap C = 1 |

Now you have your priorities. You will start with Gap B, which has the greatest need for alignment with business goals and objectives.

Figure 4-4. Sample Paired Comparison Matrix

Figure 4-5. Sample Paired Companion Matrix Ready for Making Priority Comparisons

Figure 4-6. Completed Paired Comparison Matrix

![]() Conduct project alignment to produce a plan for each project. Based on your priorities, you have identified the projects (gaps) on which to work. Now you must create a work plan for each of these projects. You may apply whatever planning process you currently use to build your timeline and identify your resource requirements.

Conduct project alignment to produce a plan for each project. Based on your priorities, you have identified the projects (gaps) on which to work. Now you must create a work plan for each of these projects. You may apply whatever planning process you currently use to build your timeline and identify your resource requirements.

![]() Conduct a front-end analysis (FEA) for each project to produce recommendations for interventions needed. Harless has developed a powerful FEA methodology you can follow. Alternatively, use all of the tools in chapter 5 of Training Ain't Performance(pp. 47-77) to conduct your front-end analysis.

Conduct a front-end analysis (FEA) for each project to produce recommendations for interventions needed. Harless has developed a powerful FEA methodology you can follow. Alternatively, use all of the tools in chapter 5 of Training Ain't Performance(pp. 47-77) to conduct your front-end analysis.

![]() Design and develop various interventions. The front-end analysis concludes with recommendations for aligning accomplishments with organizational goals and objectives. These are all means—solutions. Training Ain't Performance deals with several of these means and provides guidelines for developing those interventions. Telling Ain't Training suggests ways to create effective skills and knowledge solutions. Chapters 6, 7, 8, and 9 of this Fieldbook offer additional guidance on an array of performance interventions.

Design and develop various interventions. The front-end analysis concludes with recommendations for aligning accomplishments with organizational goals and objectives. These are all means—solutions. Training Ain't Performance deals with several of these means and provides guidelines for developing those interventions. Telling Ain't Training suggests ways to create effective skills and knowledge solutions. Chapters 6, 7, 8, and 9 of this Fieldbook offer additional guidance on an array of performance interventions.

![]() Test, revise, and implement interventions. This step is self-evident. Never implement without testing and revision.

Test, revise, and implement interventions. This step is self-evident. Never implement without testing and revision.

![]() Evaluate projects. Here Harless recommends formal verification of alignment results. If you established success criteria and metrics in your frontend analyses, these will be the guideposts for evaluation. Chapter 12 of this Fieldbook provides guidance and job aids on evaluating results.

Evaluate projects. Here Harless recommends formal verification of alignment results. If you established success criteria and metrics in your frontend analyses, these will be the guideposts for evaluation. Chapter 12 of this Fieldbook provides guidance and job aids on evaluating results.

Before we say farewell to Harless, please examine Figure 4-7. It is part of his front-end analysis. We include it because it is one of the few published items we have found where questions are raised about a present or new business goal. Note the differences between the Diagnostic FEA and the New Performance FEA.

So we leave Harless' PIP model with you. Think about it and apply it as circumstances warrant.

We have another model to examine. When you have reviewed it, we'll recommend an activity for you and your team that will challenge you to work with the various approaches to performance improvement that you've encountered.

An Activity for You

Please revisit the “Dismal Sales at HTC” case study. We have reproduced it below for your convenience.

Case Study—Dismal Sales at HTC

Samantha Solomon is the senior product manager for PC services at your

company, High-Tech Computing (HTC), a computer and peripherals manufacturer.

The new High-Availability Integrated Services (HAIS) package should be selling well. With this integrated services package, the company set goals of increasing its share of the market by 30 percent and significantly building its reputation as a high-end services provider—a critical element in its strategy to prosper in a rapidly evolving market with huge financial potential and demand.

It has taken Samantha's team almost five intensive months to sort through and pull together individual services currently being offered by HTC and its competitors. The team has carefully studied HTC's individual services; made adjustments; and bundled them into an overall, integrated, attractive PC services package. After much investigation, analysis, simulation, and argument, the team finally figured out how all the pieces fit together (for example, hardware, software, networking, communications, security, storage, and service levels). The HAIS package offers a wide choice of coverage and pricing options to customers.

Three months ago, Samantha sent out the new HAIS marketing materials, technical/reference manuals, and services and pricing options to all 400 worldwide PC services sales reps. Today, as she studies the HAIS sales figures, her mood is stormy. She anticipated 100 big-dollar sales by now. What she has is a dismal total of 15.

Samantha has summoned you to meet with her. She is firm and clear in her demand. “HAIS is not selling. Develop and deliver a solid training program and get those PC services sales reps trained. Fast! I'm thinking of a Webcast maybe or even a Webinar.”

Figure 4-7. Summary of Front-End Analysis

Using Figure 4-7, determine whether this situation is a candidate for a Diagnostic or a New Performance FEA. Write a brief rationale for your choice in the box below. We'll meet you again when you're finished writing.

The New Performance choice appears tempting. After all, the PC service sales reps have not sold HAIS packages before. However, New Performance really refers to a very different type of performance, often involving newly designated personnel or very new roles. In our “Dismal” case study, the expectation is that PC service sales reps already sell many PC services and packages. HAIS has some new characteristics, but is still a “package to be sold” like others. In Harless' sense, new performance might include

![]() creation of the new position of team leader to place between managers and workers

creation of the new position of team leader to place between managers and workers

![]() a new performance-consulting role—something never done before in any formal way in the organization

a new performance-consulting role—something never done before in any formal way in the organization

![]() establishment of an ombudsman to handle internal complaints, issues arising between the public and the organization, and whistle blowing—a radical change occasioned by the presence or threat of lawsuits.

establishment of an ombudsman to handle internal complaints, issues arising between the public and the organization, and whistle blowing—a radical change occasioned by the presence or threat of lawsuits.

If the performance to be required is in the planning stage, select New Performance. However, if the performance required is in the control stage once implemented, select Diagnostic.

Apply the steps of the Diagnostic FEA in Figure 4-7 to the “Dismal” case study. We realize that you can't go very far without data, but you can decide whether this Harless job aid works for you. We've applied it and found that if we actually went out and gathered evidence, it would help a great deal. We recommend that you store this valuable front-end analysis tool in your performance consulting toolbox.

An Activity for Your WLP Team

Share Figure 4-7 with your team. Show them how you applied it to the “Dismal” case. Discuss its application and requirements. Select a sample case study from your own environment and apply the front-end analysis tool as a group. Debrief the results in terms of usefulness, applicability, requirements, and shortcomings.

A Comprehensive Performance Improvement Model

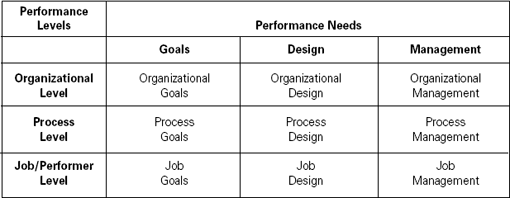

Moving on from Gilbert's eye-opening Behavior Engineering Model, you can see that Harless' PIP and FEA materials help you dig more deeply into performance issues. Let's go a step farther. One of the most important milestones in the evolution of human performance improvement was the 1995 appearance of a relatively small volume—Improving Performance: How to Manage the White Space in the Organization Chart, written by Geary A. Rummler and Alan P. Brache. Their systemic analysis of performance profoundly influenced performance-consulting thinking. They produced a model that examines the organization as a whole and identifies key factors affecting performance at the organizational, process, and individual worker levels. Their model unites all of these levels toward a single purpose: to engineer performance success. Because this is your mission, here are two useful Rummler and Brache tools for your expanding toolbox. The first of these is displayed in Figure 4-8. Its simple title, “Nine Performance Variables,” belies some deep thinking inside it.

Figure 4-8. Rummler and Brache's Nine Performance Variables

Here's how you can use this tool. Imagine that your retail company wishes to improve sales through a very personalized approach to serving the customer. It wants to launch its “new way of doing business” with great fanfare. As the WLP consultant for this project, you've been called in to train front-line staff and supervisors. You want to make sure that accomplishments will align with goals, so first you examine the key variables at the organizational level:

![]() Are the goals of the organization clear, specific, well defined, comprehensible, and feasible?

Are the goals of the organization clear, specific, well defined, comprehensible, and feasible?

![]() Is the organization designed to achieve the goals? Is the organizational structure appropriate to that end? Is adequate infrastructure in place? Are resources available to support the initiative successfully?

Is the organization designed to achieve the goals? Is the organizational structure appropriate to that end? Is adequate infrastructure in place? Are resources available to support the initiative successfully?

![]() Is the organizational management adequate for achieving performance success? Are the right senior managers in place? Are their priorities aligned? Are they credible? Supportive?

Is the organizational management adequate for achieving performance success? Are the right senior managers in place? Are their priorities aligned? Are they credible? Supportive?

The questions raised here are rather basic ones. Nevertheless, negative responses will certainly throw up red flags. You repeat your analysis at the process level:

![]() To ensure a successful performance change—from pushing our products and getting the order to a “personalized” selling and customer-handling approach—are our process goals clear? Have we specified what the outcome of our customer-handling process is/will be?

To ensure a successful performance change—from pushing our products and getting the order to a “personalized” selling and customer-handling approach—are our process goals clear? Have we specified what the outcome of our customer-handling process is/will be?

![]() Are our processes appropriate to the new approach? If we are to personalize our sales, will the process we currently have or have planned permit this?

Are our processes appropriate to the new approach? If we are to personalize our sales, will the process we currently have or have planned permit this?

![]() Are our processes managed in a way that facilitates a personalized approach? Do we have intermediaries (for example, invoicing, legal, and distribution service employees) who are part of the customer-handling process, but who are removed from the customer and only see him or her as an account number?

Are our processes managed in a way that facilitates a personalized approach? Do we have intermediaries (for example, invoicing, legal, and distribution service employees) who are part of the customer-handling process, but who are removed from the customer and only see him or her as an account number?

And now on to the individual job or performer level:

![]() Are the goals of the job and/or the performer aligned with the new approach?

Are the goals of the job and/or the performer aligned with the new approach?

![]() Is the job even designed to permit personalized, ongoing customer contact? (Or, perhaps when the sale is made, is the customer no longer the salesperson's responsibility?)

Is the job even designed to permit personalized, ongoing customer contact? (Or, perhaps when the sale is made, is the customer no longer the salesperson's responsibility?)

![]() Is the job/performer managed appropriately? (For example, although the new approach seeks to personalize the interaction, is the supervisor watching the clock and timing the length of each call?)

Is the job/performer managed appropriately? (For example, although the new approach seeks to personalize the interaction, is the supervisor watching the clock and timing the length of each call?)

Consider applying this tool in any major performance improvement or performance change issue in your organization. It presents a highly systemic approach to examining what may be affecting the behaviors and accomplishments of the performers within your organizational human performance system.

Rummler and Brache will help you dig even more deeply through a series of questions aimed at all the major “stress points” in the human performance system. These questions can be asked at macro (large) levels within the organization or at micro levels way down inside an individual unit. Figure 4-9 presents their excellent questions in a highly visual format. All of the questions target the individual performer and the factors affecting both behaviors and accomplishments.

An Activity for You

An important mission of this Fieldbook is to arm you with enough of the right tools that you can build your expertise and credibility in your organization, so we urge you to review your last project. Determine what the desired and actual performance levels were, no matter what you were asked to do or what you eventually did. Re-analyze the project situation with fresh eyes using either or both of the Rummler and Brache tools (Figures 4-8 and 4-9). Based on your review, answer the following questions:

Figure 4-9. Rummler and Brache's Questions Regarding Factors That Affect Human Performance

1. By using the tools, did I learn something new (that is, something different from or added to what I learned when I did the project)?

2. Do these tools help me approach the situation differently than before? How?

3. Now that I have these tools, would I do the project differently if I did it again? How? With what probable changes and outcomes?

An Activity for Your WLP Team

Introduce the Rummler and Brache tools to your team. Do this conceptually at first, using the explanation and descriptions we've provided in this chapter if you require them. Discuss how these tools might be applied in your work setting. Share with the team the activity you just went through employing one or both tools to your last project. Discuss implications using the three questions we posed to you. Then select a project the team has worked on in the past and do the following as a group:

![]() Determine what the desired and actual performances were, no matter what the client asked for or what was actually delivered.

Determine what the desired and actual performances were, no matter what the client asked for or what was actually delivered.

![]() Re-analyze the project situation with fresh eyes, using either or both of the tools in Figures 4-8 and 4-9.

Re-analyze the project situation with fresh eyes, using either or both of the tools in Figures 4-8 and 4-9.

![]() Pose the same three questions to your team that you answered in the individual activity.

Pose the same three questions to your team that you answered in the individual activity.

![]() Finally, draw conclusions about how the tools might be applied in your context.

Finally, draw conclusions about how the tools might be applied in your context.

The Bottom Line in Investigating Performance Blocks

Although we have limited ourselves to presenting only a few of the many models and tools that exist in the human performance improvement field, please realize that this is a rich, fertile domain with so much more to assist you. In chapters 14 and 15 of this Fieldbook, we will point you to many other resources. We stop here with those we have included so as not to create confusion for you.

What all the models and resources have in common is a systemic vision of human performance. They each endow you with means for viewing your organization and determining what factors affect desired outcomes, and what should be done to achieve accomplishments that are valued by all stakeholders.

As a performance professional, you need to broaden your skill and knowledge base continuously. To conclude, we suggest the following actions:

1. Help yourself and your team become “master craftsmen” in performance support and improvement. Like any fine craftsperson, you achieve this goal by adding more useful tools to your professional toolbox. Apply them yourself, reflect on their utility, and share them with your team.

2. Maintain a “beyond the obvious” focus at all times. Just as was true for Alice in Wonderland, nothing is quite what it seems. Challenge—very supportively and diplomatically—the problem/solution brought to you by your clients. Never forget that training as a single solution to a performance problem is often not necessary and almost never sufficient to achieve lasting human performance results.

3. Adopt a WLP Weltanschauung—a way of viewing the world or a perspective on things. It's a viewpoint you and your team adopt that

• focuses on valued accomplishments—ends and not means.

• understands from the start that simple, one-shot solutions to complex problems don't work.

• insists on analysis before designing and delivering interventions.

• requires a systemic view of performance—an investigation of all likely factors that do or potentially can affect behaviors and accomplishments.

This comprehensive vision and the application of models and tools to help your organization is the true hallmark of the performance professional.

Chapter Summary

In this chapter you became acquainted with viewpoints and tools beyond those we provided in Training Ain't Performance. Here's how you did it:

![]() You reviewed the “I would perform better if…” exercise and Thomas Gilbert's Behavior Engineering Model, but with a new purpose. You prepared to use the exercise and model to show your WLP teammates, managers, and clients the importance of variables (and interventions) beyond training (skills and knowledge acquisition) that affect not only their own but others' performance.

You reviewed the “I would perform better if…” exercise and Thomas Gilbert's Behavior Engineering Model, but with a new purpose. You prepared to use the exercise and model to show your WLP teammates, managers, and clients the importance of variables (and interventions) beyond training (skills and knowledge acquisition) that affect not only their own but others' performance.

![]() You studied Joe Harless' PIP model in some detail, and used some of his tools to identify and attack high-priority performance gaps.

You studied Joe Harless' PIP model in some detail, and used some of his tools to identify and attack high-priority performance gaps.

![]() You applied Harless' front-end analysis job aid to the specifics of a case to determine if you should conduct a Diagnostic FEA or a New Performance FEA.

You applied Harless' front-end analysis job aid to the specifics of a case to determine if you should conduct a Diagnostic FEA or a New Performance FEA.

![]() After your introduction to Rummler and Brache's nine performance variables and their factors affecting human performance, you applied one or both of these aids to a project you had undertaken.

After your introduction to Rummler and Brache's nine performance variables and their factors affecting human performance, you applied one or both of these aids to a project you had undertaken.

![]() You introduced these performance improvement models and tools to your team.

You introduced these performance improvement models and tools to your team.

![]() Finally, you pulled the main points of the chapter together with what we sincerely hope is a commitment to becoming a “master craftsperson” in human performance improvement—one determined to increase the tools in your professional toolkit; keep your eye on what is needed, not simply on what is requested; and maintain a systemic worldview at all times.

Finally, you pulled the main points of the chapter together with what we sincerely hope is a commitment to becoming a “master craftsperson” in human performance improvement—one determined to increase the tools in your professional toolkit; keep your eye on what is needed, not simply on what is requested; and maintain a systemic worldview at all times.

Bravo! There was a lot of information in this chapter and quite a few tools. They all aimed at strengthening your holistic perception of performance. They all contribute to setting the stage for the actual operational work of engineering effective performance. That's what awaits you in Chapter 5 and the chapters that follow it.