Chapter 9

Nonlearning Interventions: Emotional

This chapter

![]() presents you with a category of performance interventions that is less familiar to training and performance professionals than are learning and environmental interventions—emotional interventions

presents you with a category of performance interventions that is less familiar to training and performance professionals than are learning and environmental interventions—emotional interventions

![]() introduces a model that serves as both a diagnostic and a prescriptive tool for selecting and implementing a major form of emotional intervention—incentive systems

introduces a model that serves as both a diagnostic and a prescriptive tool for selecting and implementing a major form of emotional intervention—incentive systems

![]() provides a “recipe” for creating an incentive system intervention, and offers an example

provides a “recipe” for creating an incentive system intervention, and offers an example

![]() includes guidance on initiating workplace motivation interventions

includes guidance on initiating workplace motivation interventions

![]() suggests activities for you and your WLP team to build competency in this less-well-traveled region of human performance improvement.

suggests activities for you and your WLP team to build competency in this less-well-traveled region of human performance improvement.

Tools in this chapter include

![]() the Performance Improvement by Incentives Model

the Performance Improvement by Incentives Model

![]() a set of guidelines for applying the model

a set of guidelines for applying the model

![]() prescriptive guidelines for enhancing workplace motivation.

prescriptive guidelines for enhancing workplace motivation.

Incentives, Motivation, and Workplace Performance

The “emotional” dimensions of the workplace setting are somewhat murky and vague for most performance professionals. There are two reasons for this. The first is that most of you have come into your training and performance-support roles via previous, unrelated subject-matter expertise. Perhaps, for example, you were an excellent salesman, technician, accountant, or call center agent. Your proficiency at doing the job plus your personal characteristics and interests made you a desirable candidate for your current training/performance-support position. You may have been a training professional with appropriate academic qualifications and experience and been placed in your current post because you know about learning. Whatever your situation, it is highly unlikely that you are a motivation or incentive specialist. In our studies of training and WLP organizations, we have met very few incumbents with that form of expertise.

The second reason that the area of emotional intervention is relatively uncharted for us is that a great deal of belief, opinion, and myth inhabit this territory. When performance is not as it should be, a manager can quickly jump to the conclusion that “my people aren't motivated,” and respond to that conclusion with an order to “get me a motivational speaker to fire them up.” Other managers may interpret lack of performance when workers know how to do a job as a sign that they need some form of incentive to “get them going.” Intuition appears to prevail here, based on subjective decision making.

We spent more than a year as members of a research team studying incentives and motivation and their relationship to workplace performance. We reviewed all of the existing published research we could find and delved in depth into more than 140 companies, questioning developers and administrators of incentive systems, recipients of incentives, and recipients' supervisors about their incentive practices and results. In this chapter we share our findings with you, translating them into actionable guidelines that you may apply as a performance professional.

The Performance Improvement by Incentives Model

Business and industry in the United States spend more than $60 billion annually on formal, identifiable training programs, activities, and infrastructure. That's an impressive sum. But the amount pales in comparison with the estimated $117 billion in annual expenditures for tangible incentive programs aimed at encouraging workers of every variety to perform well—or at least better. The interesting (and frightening) aspect of this is that almost all of the decisions about which incentives to use, for whom, and how they should be applied are made with very little or no reference to research on incentive use. Furthermore, most decisions regarding incentives are made unsystematically, rarely on the basis of data from previous incentive ventures. The bad news is that enormous quantities of money are spent inefficiently to attain desired results from employees and third-party partners. The good news is that this state of affairs offers wonderful opportunities for you, the performance professional, to clean things up.

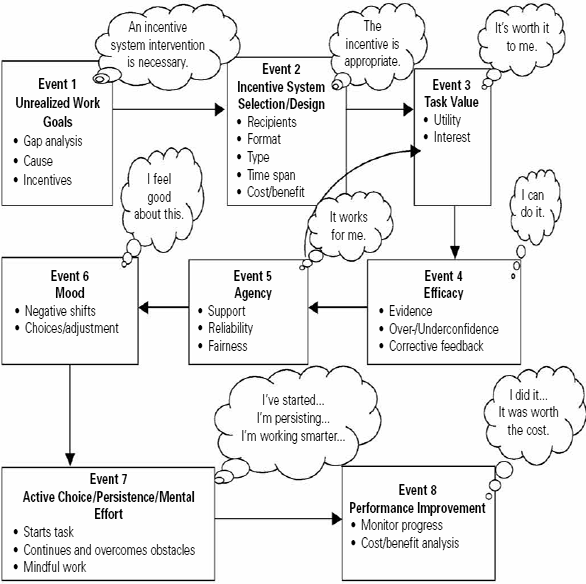

So to help you prepare for this opportunity, let's take a look at the Performance Improvement by Incentives (PIBI) Model. Derived from research on motivation and incentives, this model has been validated through an examination of best practices in an array of workplace organizations.1

Overview of the PIBI Model

You can use the PIBI Model for both diagnostic and prescriptive purposes. It helps you determine whether an incentive-type intervention is appropriate, guides you step-by-step to develop and implement a relevant incentive system with a high probability of success, and points out where and how to troubleshoot your incentive system intervention if difficulties arise. Figure 9-1 illustrates the eight major “events” for selecting, implementing, monitoring, and troubleshooting incentive system interventions.

In Table 9-1 there is a brief description of what happens in each of the model's eight events.

Creating Your Own Incentive System

The PIBI Model helps you systemically view how all the events of an incentive system intervention fit together, from initial findings in the front-end analysis to verification of improved performance. What follows here is a “recipe” for creating an incentive system of your own. The recipe is laid out as an outline of prescriptive task steps that very closely match the PIBI Model, event by event. (Some of the words are different from those used in the model. This is to make doing—that is, creating an incentive system intervention—a bit easier.) We recommend you read through this recipe as you would in cooking or baking to obtain a sense of the flow and sequence of steps. Picture what is happening at each step. Note that we divide each event of the PIBI Model into three phases: implementation(what you do), monitoring(what you check), and repair(what you fix or cause to have happen to make things work). Each event also contains principles for you to apply as you proceed. Following this recipe is an example of its application.

Figure 9-1. The Eight Events That Make Up the Performance Improvement by Incentives Model

Table 9-1. PIBI Model—Descriptions of the Eight Events

| Event | What Happens |

| Event 1: Unrealized work goals |

|

| Event 2: Incentive system selection/design |

|

| Event 3: Task value |

|

| Event 4: Efficacy |

|

| Event 5: Agency |

|

| Event 6: Mood |

|

| Event 7: Active choice/ persistence/mental effort |

|

| Event 8: Performance improvement |

|

An Incentive System Intervention Recipe

Event 1: Unrealized Work Goals

1.1 Implementation

1.1.1 Identify unrealized work goals based on an analysis of the gap between current and desired performance.

1.1.2 Specify performance goals that are concrete and challenging, but feasible.

1.2 Monitoring

1.2.1 Determine if gap is the result of skills/knowledge deficiency.

1.2.2 Determine if gap is caused by environmental obstacles or deficiencies.

1.2.3 Determine if gap is motivation based.

1.3 Repair

1.3.1 For a gap based on skills/knowledge deficiency, provide training and/or job aids.

1.3.2 For a gap based on environmental obstacles or deficiencies, remove obstacles or correct deficiencies.

1.3.3 For a gap based on motivational deficiencies, consider using an incentive system.

Principles:

It is rare for a single intervention to be sufficient for achieving workplace results. Even if the major cause for the gap between desired and actual performance is motivation based, and incentives are appropriate, always verify that skills/knowledge and environmental conditions also are sufficient to achieve goals.

The more challenging the goal, the greater the effort individuals or teams must exert. However, they must perceive the goal as possible to achieve with maximum effort.

Event 2: Incentive System Selection/Design

2.1 Implementation

2.1.1 Specify the target recipients of the incentives. (When feasible, teams are the preferred target.)

2.1.2 Involve management and (as culturally appropriate) targeted recipients of the incentives in the incentive system selection/design process.

2.1.3 Select incentives that are workable and acceptable to the organization and attractive to the targeted recipients. The possible incentive types are monetary, gift/travel, and recognition. Monetary is often the preferred choice. Verify this for your setting.

2.1.4 Select from the three incentive system formats: quota, piece-rate, contest. When feasible, quota is the preferred choice.

2.1.5 Specify the time span: long term (greater than one year), intermediate term (six months to one year), or short term (less than six months). When possible, a long-term time span is preferred.

2.2 Monitoring

2.2.1 Verify to ensure that targeted recipients, supervisors, and organizational management understand the details of the incentive system.

2.3 Repair

2.3.1 Re-communicate incentive system specifics to individuals or units that demonstrate a lack of understanding about the incentive system.

Principles:

Although the participation of the targeted recipients generally is desirable in selecting incentives and/or designing the incentive system, the level, nature, and process of participation must be appropriate to cultural, national, and organizational norms. For multicultural and global organizations, verify to determine the appropriate level of participation for the various affected groups.

An incentive system may be composed of more than one type of incentive. It may include a combination of monetary, gift/travel, and recognition elements.

Event 3: Task Value

3.1 Implementation

3.1.1 Communicate to target recipients, their supervisors, and all other concerned parties the nature of the incentive system and its mechanics so that the link between the incentive(s) and the desired improved performance is clear and unambiguous.

3.1.2 Explain that the incentive offered is intended to create “utility” value for achieving beyond current levels of performance.

3.2 Monitoring

3.2.1 Verify that utility value has been established. Verify that targeted recipients value the incentive enough to increase their performance and maintain it in the face of distractions and other priorities.

3.2.2 Check to find if interest is waning.

3.3 Repair

3.3.1 Revise details of the incentive system to increase utility.

Principle:

The less the inherent interest in the task to be performed, the more there is a need for a valued incentive to be linked to it to drive performance. The incentive serves a utility purpose—it replaces interest in the task with interest in money or gifts. Communicate a clear and strong relationship between the two.

Event 4: Efficacy

4.1 Implementation

4.1.1 Provide evidence from the past performance of the targeted individuals and teams that they are capable of achieving at the desired level, and/or describe the success of other individuals and teams similar to the targeted recipients.

4.2 Monitoring

4.2.1 Monitor team and individual confidence that they can achieve the desired performance levels and earn the incentives. Watch for evidence of underconfidence or overconfidence.

4.2.2.1 Determine if there is evidence of underconfidence in the form of errors in performing the task, a gradual withdrawal from performing the task, and/or a negative mood shift when talking about the performance goals or incentives.

4.2.2.2 Determine if there is evidence of overconfidence in the form of errors—and when confronted with such errors or poor performance, there is a refusal to accept responsibility or the worker's mood shifts to anger when talking about the task or the incentive program.

4.3 Repair

4.3.1 Focus on task performance and specify what is necessary to increase performance. Do not focus negatively on the person or team.

4.3.2 For underconfidence, break the task into smaller, more manageable components, and provide help.

4.3.3 For overconfidence, provide convincing evidence that the strategy performers are using is flawed, and demonstrate that another approach will succeed.

Principles:

The greater the confidence of the individuals and teams to achieve desired performance improvement goals, the higher the probability of their achieving success, especially with respect to challenging goals. But overconfidence is a performance stopper. Overconfident people often apply the wrong strategy (or maintain inappropriate beliefs) and do not take responsibility for their failure to achieve the performance goal.

The less confidence the individuals and teams have that they can achieve desired performance improvement goals, the greater the need to provide support by breaking the feared task into smaller tasks and offering help. This strategy often raises the confidence level.

Event 5: Agency

Note: The greatest number of incentive system breakdowns generally occur in this event.

5.1 Implementation

5.1.1 Provide management support for task performance in the form of clear communication about the incentive system, fair and equitable management of the system, effective work processes, adequate resources, and assistance as required and feasible.

5.1.2 Use a transparent administrative system for tracking achievements and rewards.

5.1.3 Communicate individual and team progress on a regular and frequent schedule.

5.2 Monitoring

5.2.1 Develop an effective system in which targeted recipients are encouraged to report concerns and problems associated with organizational support of employee performance and its management of the incentive system.

5.2.2 Do not punish people for reporting problems, even if the problems turn out not to be substantive.

5.3 Repair

5.3.1 Thank the people who report problems and investigate them.

5.3.2 Report the results of your problem analysis to the person or team who reported it.

5.3.3 Make a plan to remove barriers to performance or provide convincing evidence that perceived barriers do not exist.

Principle:

Perceived implementation breakdowns result in targeted recipients reassessing task value downward. This has a negative effect on task performance and defeats the purpose of the incentive system.

Event 6: Mood

6.1 Implementation—none

6.2 Monitoring

6.2.1 Monitor workplace climate for negative mood changes (anger, negativity).

6.3 Repair

6.3.1 Let people decide how to do their jobs and decorate their work space (within reason and if they do not intrude on others).

6.3.2 Adjust environment to improve workplace climate (for example, permit listening privately to music while working, if possible).

6.3.3 Provide positive, energetic, and fair managers and work models.

Principle:

Workplace climate and individual mood can have an effect on motivation and performance. Mood is often a strong indicator of performance shifts and motivation. When mood becomes sufficiently negative, performance slows or stops. Strong positive mood is not essential, but strong negative emotion must be avoided.

Event 7: Active Choice/Persistence/Mental Effort

7.1 Implementation—none

7.2 Monitoring

7.2.1 Verify that targeted recipients are

- choosing to perform the targeted tasks in the desired manner

- persisting at the targeted tasks

- mentally engaged (“using their heads”) to achieve desired results.

7.3 Repair

7.3.1 Cycle back through the events of the PIBI Model to identify the cause(s) for failure of active choice/persistent behavior/exertion of mental effort.

Principles:

Tasks for which incentives have been provided may lead to neglect of other essential tasks that carry no incentives. Monitor to ensure that targeted recipients perform all necessary tasks related to the job. Make receipt of incentives contingent on this accomplishment.

A decline in active choice, persistence, and/or mental effort signals a need to repair the value, the agency, and/or the efficacy (see Events 3, 4, and 5).

Event 8: Performance Improvement

8.1 Implementation—none

8.2 Monitoring

8.2.1 Monitor progress continually.

8.2.2 Monitor the cost/benefit analysis of the incentive system.

8.3 Repair

8.3.1 Review Events 1 and 2 when performance does not increase. It is possible that the gap analysis was incorrect and that people lack adequate knowledge and skills to perform or that the work processes or materials are missing or inadequate. It is also possible that the incentive is not creating value for the task, and so requires adjustment.

Principle:

The success of the incentive system is judged by the attainment of performance goals at a cost that is less than the value of the results. For example, you wouldn't want to put in place an incentive system that costs $500,000 when the value of anticipated results fell short of that figure. Ongoing monitoring of progress toward goals and communication of successes to targeted recipients and other affected groups are necessary to sustain incentive system momentum.

An Incentive System in Action

Although the PIBI Model recipe is sound and it works, it may be difficult to imagine it in action. The scenario that follows brings to life an application of the steps you just reviewed. As you read through the Lightning Sales scenario, mentally place yourself in the context and imagine that this is your project.

The Scenario: Lightning Sales

Organization: Lightning Electronics

Situation: Lightning produces a superior line of products at very reasonable prices (20-30 percent less than the big-name manufacturers). It also has a very good reputation for technical support. Given the current economic conditions in which everyone is trying to reduce equipment costs, and based on various market studies it has conducted, Lightning's management believes that there is a huge opportunity to increase sales of its peripheral products (such as printers, plotters, scanners, keyboards, hard drives, and monitors) through independent vendors. Lightning knows that customers tend to go for well-known brands, and that those popular manufacturers often provide special incentives to sales reps in the form of prizes, meals, and merchandise.

Desired performance improvement: Increase sales of Lightning peripheral equipment through authorized vendors. Increase sales by 200 percent.

Means: Launch an effective incentive system to encourage sales reps to push Lightning products.

Targeted incentive recipients: Sales representatives for outside vendors who sell a broad variety of peripheral equipment from multiple manufacturers, many of which have far greater name-brand recognition than Lightning has.

Prescriptive Steps

Event 1: Unrealized Work Goals

1.1 Implementation

1.1.1 There is a gap of 200 percent between actual and possible sales volumes.

1.1.2 The desired performance goal is concrete and specific (a 200 percent increase in sales), challenging (a rather large annual increase in sales), but feasible (according to market analysis).

1.2 Monitoring

1.2.1 The sales gap is not the result of skill or knowledge deficiencies because there is no evidence that the sales staff is poorly trained or is skillfully inadequate.

1.2.2 There are no environmental obstacles keeping the sales reps of the outside vendors from selling Lightning products.

1.2.3 The gap is motivation based. The sales reps are aware of the high quality and low cost of Lightning's products, but they receive incentives from competing manufacturers to sell their products.

1.3 Repair

1.3.1 No additional training is required.

1.3.2 No environmental obstacles must be removed.

1.3.3 The use of an incentive system is warranted because the performance deficit is motivation based and because other manufacturers offer incentives for the sale of their products.

Event 2: Incentive System Selection/Design

2.1 Implementation

2.1.1 Incentives will be offered to all outside vendor sales reps individually. Lightning is convinced that sales will increase because the sales reps can earn the same incentives as with other manufacturers, and they can market more aggressively to consumers a product of higher quality at a lower cost—features that will boost sales.

2.1.2 Lightning management does not involve outside vendor sales reps in the design of the incentive system because they are located in retail outlets throughout the United States. Lightning surveys them regarding their openness to an incentive system. Survey results reveal a widely positive response.

2.1.3 Lightning does not want to spend more in incentives for a given volume of sales than do competing manufacturers, so the chosen incentives will match (in cost and kind) the various gift and travel incentives offered by the competing manufacturers.

2.1.4 The format will be a quota system. All sales reps who sell Lightning products at rates greater than the “average” sales rep (as determined by an examination of sales data) will be eligible for gifts of their choosing that increase in quality and cost as their volume of sales increases.

2.1.5 Because Lightning's incentive system is a match for the incentive systems of other manufacturers, the system will last indefinitely.

2.2 Monitoring

2.2.1 Formal letters are to be mailed to each sales rep explaining the particulars of Lightning's new incentive system. Additional letters will be sent to each store's sales manager to distribute to newly hired sales personnel. Lightning Electronics will verify receipt of the letters and encourage the sharing of information among sales reps and managers. Lightning also will verify that there is interest in and approval of what is being proffered.

2.3 Repair

2.3.1 A follow-up letter is mailed to each sales manager to verify that sales reps have received letters from Lightning. If there are any concerns about appropriateness of the incentive system, Lightning will make suitable modifications based on sales rep and manager input.

Event 3: Task Value

3.1 Implementation

3.1.1 Formal letters are mailed to each sales rep, explaining the particulars of Lightning's new incentive system. Additional letters are sent to each store's sales manager to distribute to newly hired sales personnel.

3.1.2 A feature of the letters is mention of how the incentives are intended to motivate the sales reps to make extra effort to market Lightning products. Also stressed are Lightning's high quality and excellent service reputation, which create high consumer value.

3.2 Monitoring

3.2.1 A return-requested survey form asking for questions or comments is included with the letter sent to sales reps and sales managers. Lightning uses the survey results as an indicator of how well the reps understand the utility value of the incentives offered. The interest that sales reps have in selling computer products for a living is not one of Lightning's concerns. Their only concern is with the utility value the sales reps have for Lightning's products.

3.3 Repair

3.3.1 If future sales data indicate that there are stores that have not shown any marked increase in sales, or that have not made any claims on incentive gifts, Lightning will verify that those sales reps have been properly informed of the incentive system.

Event 4: Efficacy

4.1 Implementation

4.1.1 Lightning mails copies of trade journal articles that demonstrate how effective incentives can be in greatly boosting sales. Additionally, Lightning asks sales managers to scour their own sales records to see how sales of competing manufacturers' products increased when incentives were first offered.

4.2 Monitoring

4.2.1 Lightning will ask vendor sales managers to determine if sales reps doubt they can increase sales of Lightning products.

4.2.1.1 Sales managers will be asked to report to Lightning if there are reps who display signs of underconfidence about selling Lightning products, such as reductions in sales efforts, or sour talk about Lightning's products and its incentive system.

4.2.1.2 Sales managers will be asked to report to Lightning if there are representatives who are displaying signs of overconfidence about selling Lightning products, such as expecting to receive very expensive incentive gifts, bragging about how much they can sell, and blaming their failures on Lightning's “lousy” product quality.

4.3 Repair

4.3.1 A few weeks into the program, Lightning will send a general troubleshooting letter to sales reps and their managers. The letter will address various difficulties that sales reps may be encountering in increasing sales.

4.3.2 Part of the letter will address underconfident reps and will seek to provide sales remediation information.

4.3.3 The other part of the letter will seek to reduce levels of overconfidence by explaining how reasonable increases in sales can be accomplished.

Event 5: Agency

5.1 Implementation

5.1.1 A select number of Lightning's customer service personnel are made available to the sales representatives to assist them with any questions or concerns they might have about the operation of the incentive system.

5.1.2 Because Lightning knows that if its recordkeeping is inaccurate, sales representatives will reassess the value of its incentive system and probably focus their attention on selling competing products, management will devote a specific number of accountants to tracking and monitoring sales, revenues, and the earning and awarding of gift incentives.

5.1.3 Monthly progress reports will be mailed to all vendor sales managers, enumerating the year-to-date sales of Lightning products for each sales rep.

5.2 Monitoring

5.2.1 Lightning's customer service personnel, as well as its Website and email address, can be used by sales reps to get answers to questions or express concerns about the incentive system.

5.2.2 It is Lightning's policy to investigate all concerns raised, and to report to the complainant the results of the investigation without prejudice.

5.3 Repair

5.3.1 Lightning sends out small notes or cards thanking sales representatives (who have identified themselves) for their interest in the incentive program.

5.3.2 Results are reported to sales representatives who made the original complaint.

5.3.3 Lightning's management is cataloging complaints and concerns to determine if there is a pattern to them. From the catalogued complaints and concerns, management will develop a plan to correct the problems.

Event 6: Mood

6.1 Implementation—none

6.2 Monitoring

6.2.1 It is not possible for Lightning to monitor the mood of sales reps directly. Therefore, it is relying on sales managers to report mood changes, and on reps to send in complaints via email, Internet, phone, or fax.

6.3 Repair

6.3.1 Lightning is not telling the outside vendor sales reps how to sell Lightning's products. The sales reps are free to use whatever marketing or sales strategy they wish to meet their sales objectives. Lightning does, however, provide excellent sales and technical documentation, as well as efficient sales aids.

6.3.2 Lightning does not involve itself in details of the reps' physical work environments.

6.3.3 Lightning encourages the sales managers to speak with their sales reps to stimulate participation in the new incentive system.

Event 7: Active Choice/Persistence/Mental Effort

7.1 Implementation—none

7.2 Monitoring

7.2.1 Via the monthly reports with aggregated and individual data, each sales manager and sales rep is made aware of his or her total sales, the kinds of gifts that could be earned, and how much progress needs to be made to reach particular desired incentives.

7.3 Repair

7.3.1 If failures to raise sales persist, then Lightning will reassess the details of the entire incentive system and take appropriate corrective measures.

Event 8: Performance Improvement

8.1 Implementation—none

8.2 Monitoring

8.2.1 Through its accounting system and monthly reports, Lightning will track sales data and deliver those data to its vendors' sales reps.

8.2.2 Lightning will perform a quarterly cost/benefit analysis to determine if sales have increased, how much has been spent on incentives, and if maintenance of the incentive system is warranted.

8.3 Repair

8.3.1 If progress is not being made toward meeting the work goal, or if the system fails the cost/benefit analysis, then Lightning will reassess the system and its stated work goals.

An Activity for You

Creating and implementing a complete incentive system intervention is very desirable, but it's most likely beyond the realm of feasibility for you at this point. What you can do, however, is review past and current projects to determine if any of them might have fared better if an incentive system had been devised. What indicators were present to suggest this to you? Imagine that you had a mandate to develop an incentive system to meet the desired performance goals of the project. Apply the PIBI Model recipe to it and mentally walk through each of the events. Decide what would have to be done, concretely, to achieve success.

An Activity for Your WLP Team

Bring your team together to examine the PIBI Model, the recipe, and the Lightning Sales example. Discuss the roles that team members might play in helping develop and implement an incentive system intervention. Then as a team find out if there is a current incentive program within your organization. As investigators, discover as much about it as you can. Here are some questions for which you should obtain responses:

- In what part of the organization has the incentive system been implemented?

- Why was an incentive system selected?

- What is the desired performance outcome?

- Who selected the incentives? Were recipients involved in any way in the selection?

- On what basis was the incentive system selected (for example, previous success, collected data, or vendor recommendation)?

- How was the incentive system introduced?

- What attempts were made to ensure the appropriate levels of task value, efficacy, and agency?

- Is the incentive system working well? What are the process and results indicators?

- Has a cost/benefit analysis been conducted? What is the ROI?

- Based on all the information you have gathered, what is working and what is not?

As a team, apply the PIBI Model and determine what you would do differently. Be systematic in your thinking and planning. By going through this exercise for a current or recent incentive initiative within your organization, you will emerge more competent and confident to add incentive system design and development to your professional toolbox.

Motivational Interventions

In chapter 8 of Training Ain't Performance(pp. 128-130 and 133), we briefly introduced emotional interventions and discussed motivation. This is a somewhat slippery term with many connotations attached to it, so let's revisit it in greater depth. This will help you create some motivational interventions that, believe it or not, are relatively easy to develop and implement.

Motivation—What Is It?

Essentially, motivation is an internal state that triggers in us the desire to do something—“the push from within.” Motivation drives us. It's a vital part of performance. It may be intrinsically driven—we want to do something because of our natural instincts and desires—or extrinsically stimulated—a reward that we would like to obtain is attached to successful performance. Because people are often very different in their interests and desires, what motivates one person may not be appealing at all to someone else.

Although the following examples are fairly superficial, we are asking you to decide whether the person would be intrinsically motivated to perform or would require some extrinsic motivational agent (check one).

Here are the likely correct responses:

Numbers 1 and 2 are fairly obvious. Few teenagers naturally want to wash dishes. An avid opera fan probably would wish to listen to a highly rated, new recording without some extrinsic agent. Number 3, the service-oriented agent probably wouldn't want to be a salesperson—so she'd need an extrinsic motivating agent that has meaning and value to her. Conversely, the sales rep in number 4 would most likely enjoy selling new products. In number 5, our guess is that the manager would not naturally wish to spend her time coaching weak performers, but this is a guess—it could go either way.

Our aim in the exercise above was to give you practice with the concepts of intrinsic and extrinsic motivators. Now let's apply and, to some extent, manipulate them.

Continuing with the term and concept of motivation, research indicates that there are three major components that affect it: value, confidence, and mood. Here is what we wrote in Training Ain't Performance(p. 128):

![]() Value—how highly a person values the desired performance. The more highly he or she values it, the greater the motivation.

Value—how highly a person values the desired performance. The more highly he or she values it, the greater the motivation.

![]() Confidence—how strongly a person feels she or he will be successful in performing. Under- or overconfidence lowers motivation. The optimal motivating state is one of challenge along with an expectation of success through applied effort.

Confidence—how strongly a person feels she or he will be successful in performing. Under- or overconfidence lowers motivation. The optimal motivating state is one of challenge along with an expectation of success through applied effort.

![]() Mood—a person's emotional state when required to perform. The more positive the mood the more motivated. Workplace conditions and climate affect mood.

Mood—a person's emotional state when required to perform. The more positive the mood the more motivated. Workplace conditions and climate affect mood.

This leads directly to how the performance professional can intervene at the motivational level. Table 9-2 lists each of the three key factors and suggests a suitable form of intervention. It is predicated on two important prerequisites:

![]() You have conducted a front-end analysis and found evidence of a lack of motivation to perform as desired.

You have conducted a front-end analysis and found evidence of a lack of motivation to perform as desired.

![]() You have investigated the lack of motivation (using interviews, observation, focus groups) and discovered that there is a lack of value attributed to the desired performance, a lack of confidence in being able to perform, an overconfidence that leads to neglect and errors, or a negative mood that depresses motivation—or perhaps a combination of these factors.

You have investigated the lack of motivation (using interviews, observation, focus groups) and discovered that there is a lack of value attributed to the desired performance, a lack of confidence in being able to perform, an overconfidence that leads to neglect and errors, or a negative mood that depresses motivation—or perhaps a combination of these factors.

If these prerequisites have been accomplished, use Table 9-2 to determine your choice of interventions.

Motivation to perform begins with recruiting, selecting, and hiring the right people for the job. If there is endemic lack of motivation, examine the hiring and promotion criteria and practices. Although motivational interventions such as those listed in Table 9-2 can improve motivation, they can't overcome the innate characteristics of inappropriately selected performers.

Table 9-2. Motivational Interventions

| Situation Requiring Intervention | Motivational Intervention |

| Lack of personal value |

|

| Lack of confidence |

|

| Overconfidence |

|

| Negative mood |

|

Putting Emotional Interventions Together

The overall environment and culture of the organization along with its myriad practices establish a large number of conditions affecting the emotional side of performance. The performance professional must attend to emotional factors that influence how people work and what they accomplish. When you are a performance professional, rebuilding the organization is beyond the scope of your job description. More realistically, when improved desired performance is the issue, you have the responsibility to identify all the major factors that affect the gap between desired and current performance. If in your front-end analysis or during later phases of your work you discover emotional factors at play, you must deal with them. Two main groupings of interventions are incentive systems and motivational changes. Both of these are less familiar to training and WLP groups. Now you have some guidelines and tools to help you grow in this emotional arena.

An Activity for You

Identify a person in the organization whose performance is not at the desired level. Conduct an informal front-end analysis. Determine if there is a motivational dimension to the lack of performance. If not, move on to another person until the motivational component appears. Using Table 9-2, determine which of the underlying motivational factors are present. Select the interventions you would apply. Share your findings with that person's manager. Implement the interventions. Monitor results and, without identifying the person in question, share the results with your WLP team.

Chapter Summary

This chapter dealt with a set of performance improvement interventions less well known than those of the previous two chapters. Emotional interventions stretch us as performance professionals. They also contribute immensely to the value we can offer our clients. In the course of this chapter,

![]() you were introduced to the emotional side of performance improvement with an explanation of why this is a road less traveled for most of us.

you were introduced to the emotional side of performance improvement with an explanation of why this is a road less traveled for most of us.

![]() you encountered the PIBI Model derived from research on incentive use and best practices in business and industry.

you encountered the PIBI Model derived from research on incentive use and best practices in business and industry.

![]() you examined the eight “events” of the PIBI Model and acquired some new vocabulary—task value, utility, efficacy, and agency.

you examined the eight “events” of the PIBI Model and acquired some new vocabulary—task value, utility, efficacy, and agency.

![]() you received a recipe for developing and implementing an incentive system.

you received a recipe for developing and implementing an incentive system.

![]() having examined an incentive system in action, you reviewed a past or current project in which an incentive system intervention might have been/might be relevant, and planned how you might intervene, using the PIBI Model and guidelines.

having examined an incentive system in action, you reviewed a past or current project in which an incentive system intervention might have been/might be relevant, and planned how you might intervene, using the PIBI Model and guidelines.

![]() you engaged your WLP team in an investigative exercise by examining a recent or current incentive program in your organization and determining, with the PIBI Model to assist you, how the team might have proceeded differently.

you engaged your WLP team in an investigative exercise by examining a recent or current incentive program in your organization and determining, with the PIBI Model to assist you, how the team might have proceeded differently.

![]() you explored motivational interventions and, for practice, applied your learning to a person whose motivation was lacking.

you explored motivational interventions and, for practice, applied your learning to a person whose motivation was lacking.

With this chapter we conclude the examination of nonlearning interventions. In chapter 10 we turn to issues of consulting. A major transformation must take place to move from being a training group that responds to client requests by churning out training products to performing a more consultative service. This is what awaits you when you turn the page.

1. All of the preceding information and the PIBI Model itself have been derived from a study funded by SITE Foundation and sponsored by the International Society for Performance Improvement. Results of the study have been published in Stolovitch, Clark, and Condly 2002.