Chapter 10

From Training Order-Taker to Performance Consultant

This chapter

![]() defines what it means to be a WLP consultant

defines what it means to be a WLP consultant

![]() helps you determine what kind of performance consultant you are

helps you determine what kind of performance consultant you are

![]() directs you in looking both backward and forward in your work to identify how you might have acted or will be able to act differently as a professional performance consultant

directs you in looking both backward and forward in your work to identify how you might have acted or will be able to act differently as a professional performance consultant

![]() provides you with a number of performance-consulting tools and guidelines

provides you with a number of performance-consulting tools and guidelines

Tools in this chapter include

![]() a consulting inquiry or request sheet

a consulting inquiry or request sheet

![]() a set of initial meeting guidelines

a set of initial meeting guidelines

![]() a proposal outline

a proposal outline

![]() guidelines for reporting to clients

guidelines for reporting to clients

![]() guidelines for making presentations to clients.

guidelines for making presentations to clients.

What Does It Mean to Be a “Consultant” in WLP?

![]()

In Training Ain't Performance(chapters 6 and 9), we helped you examine the current role you play and determine if it is more one of a training order-taker or one of a consultant focused on helping clients achieve performance results. Here's a quick way to assess yourself. Place a checkmark beside the description that more accurately fits you:

![]() A. I evaluate my success at work by the speed with which I develop training, the number of participants in my sessions, the scores they get on tests, the ratings my programs receive, and the number or percentage of trainees certified or the compliance requirements met.

A. I evaluate my success at work by the speed with which I develop training, the number of participants in my sessions, the scores they get on tests, the ratings my programs receive, and the number or percentage of trainees certified or the compliance requirements met.

![]() B. I evaluate my success at work by the measurable effect my interventions have in terms of results valued by my clients, their performers, my organization, and, when possible, our customers.

B. I evaluate my success at work by the measurable effect my interventions have in terms of results valued by my clients, their performers, my organization, and, when possible, our customers.

If you selected A, you are definitely in the training order-taker camp where success is judged by the speed and degree to which a training order is “filled.” If youselected B, you are solidly in the performance-consulting camp where what matters is not what you did but what your performers and the organization accomplished. By assuming the role of “consultant” in the WLP world, you are no longer judged by activity alone, but by the valued accomplishments of your performers. It's a frightening position to occupy. In a sense you become the vehicle by which others arrive at success. But what you do is of immense value to all stakeholders, including you.

The Value Add of Performance Consulting

Examine the list below that presents some statements of the value that you add in assuming a performance-consulting role:

![]() You guide clients to separate the ends they wish to achieve from the intuitively selected (and often inappropriate or incomplete) solutions they ask for, and then you help them focus on those ends.

You guide clients to separate the ends they wish to achieve from the intuitively selected (and often inappropriate or incomplete) solutions they ask for, and then you help them focus on those ends.

![]() You help your clients articulate success criteria and meaningful metrics to verify whether their valued ends have been achieved. This, in turn, enables them to display meaningful results to their managers, customers, and workers.

You help your clients articulate success criteria and meaningful metrics to verify whether their valued ends have been achieved. This, in turn, enables them to display meaningful results to their managers, customers, and workers.

![]() You educate your clients, opening their eyes to an entire spectrum of means for attaining their goals.

You educate your clients, opening their eyes to an entire spectrum of means for attaining their goals.

![]() You offer a broad menu of interventions that equip your clients to attack their performance gaps more systematically than they could with simple “miracle cures.” This increases their probability of performance success.

You offer a broad menu of interventions that equip your clients to attack their performance gaps more systematically than they could with simple “miracle cures.” This increases their probability of performance success.

![]() You save time and money. Your aim is to achieve maximum impact at minimum cost in time, resources, and dollars.

You save time and money. Your aim is to achieve maximum impact at minimum cost in time, resources, and dollars.

![]() You help your clients, the targeted performers, and the organization optimally leverage their human capital potential by focusing on efficient attainment of results rather than on activities (such as training) that may be unnecessary or insufficient to do the job.

You help your clients, the targeted performers, and the organization optimally leverage their human capital potential by focusing on efficient attainment of results rather than on activities (such as training) that may be unnecessary or insufficient to do the job.

Your role as a consultant in WLP is so much richer than that of training order-taker. It's no wonder the training world is rapidly evolving in this direction.

Revisiting the Competency Areas and Critical Characteristics for Performance Consulting

![]()

In Training Ain't Performance(chapter 9, p. 139), we gave you a worksheet listing 16 performance-consulting competency areas. Achieving all of the value add we cited in the previous section requires that you build strong professional competencies to serve your clients most fully. In this Fieldbook we go beyond what we covered in Training Ain't Performance to clarify how each competency, in and of itself, adds value for your client, the performer, the organization, and, as appropriate, the customer. Review these competencies and their value here in Table 10-1. The information in the table serves two purposes: to reinforce your need to build strength in each competency; and to demonstrate to your clients, who are often impatient and want a “quick fix,” that what you do benefits them beyond their current expectation levels.

Table 10-1. Performance-Consulting Competencies and the Value Add

| Competency | Value Add |

| 1. Determine performance improvement projects that are appropriate to tackle |

|

| 2. Conduct performance gap analysis |

|

| 3. Assess performer characteristics |

|

| 4. Analyze the structures of jobs, task, and content |

|

| 5. Analyze the characteristics of a learning/working environment |

|

| 6. Write statements of performance intervention outcomes |

|

| 7. Sequence performance intervention outcomes |

|

| 8. Specify performance interventions and strategies |

|

| 9. Sequence performance improvement activities |

|

| 10. Determine resources appropriate for performance improvement activities and help obtain them |

|

| 11. Evaluate performance improvement interventions |

|

| 12. Create a performance improvement implementation plan |

|

| 13. Plan, manage, and monitor performance improvement projects |

|

| 14. Communicate effectively in visual, oral, and written forms |

|

| 15. Demonstrate appropriate interpersonal, group process, and consulting skills |

|

| 16. Promote performance-consulting and human performance improvement as a major approach to achieving desired results in organizations |

|

![]()

In addition to the added value that the 16 performance-consulting competencies bring to a project and all its stakeholders, the competencies also define the 10 vital characteristics displayed by outstanding performance consultants. Table 10-2 summarizes these characteristics, drawn from Training Ain't Performance(p. 141). As in the previous table, we add here in brief form what value they provide to clients, performers, the organization, customers, and all other direct or indirect stakeholders.

As a performance professional—a performance consultant—you can effect large changes within your organization. These competencies and characteristics are your own personal targets. Keep in mind the added value that each one brings to you and your clients.

![]()

An Activity for You

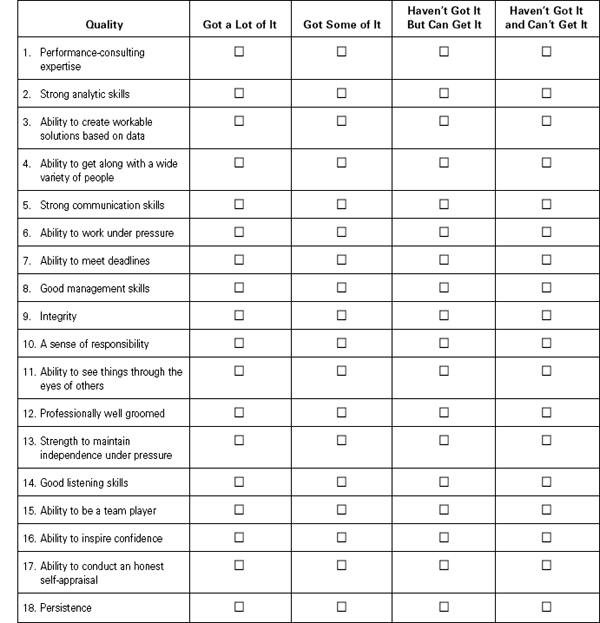

If you have many lower ratings, You have examined the characteristics required of a performance consultant, as presented in Training Ain't Performance(p. 141) and in Table 10-2. Now let's bring things a little closer to home. Do you have the potential to be a good performance consultant? Assess yourself using Worksheet 10-1, but don't do it alone. None of us is the best judge of ourselves. We all require a credible outsider to maintain a balanced view of who we are. So, find a person you trust—a manager, mentor, colleague, client you know to be objective. Together, review the 18 items on the worksheet. For each quality listed there, check the box under the rating that you and your helper believe best describes you. Be sure to listen to the person helping you because your likely inclination will be to score yourself lower than you should. Most competent, skilled professionals underrate their own abilities. High achievers frequently feel that they're “frauds,” pulling the wool over people's eyes. And a rare few of you will overrate yourself. Trust your rating partner.

It doesn't matter if you don't score “Got a Lot of It” on every quality. Few performance professionals do. For most projects you don't have to have all of these qualities at a high level—but of course it's worthwhile to strive for excellence.

Table 10-2. Performance-Consulting Competencies and the Value Add

| Characteristic | Value Add |

|

1. Is focused on client need:

|

|

|

2. Is cause conscious, not solution focused:

|

|

|

3. Is able to maintain a system perspective:

|

|

|

4. Is capable of involving others (authority figures, knowledgeable individuals) appropriately

|

|

|

5. Is organized, rigorous, and prudent:

|

|

|

6. Is sensitive to the need to verify perceptions:

|

|

|

7. Is able to sort out priorities.

|

|

|

8. Is diplomatic and credible:

|

|

|

9. Is generous in giving credit to others:

|

|

|

10. Is principled but flexible:

|

|

Worksheet 10-1: Identifying Your Performance-Consulting Qualities

Instructions: Place a checkmark in the appropriate column to describe the amount of the quality you believe you possess or can develop.

If you have many lower ratings, especially “Haven't Got It and Can't Get It” ones, these should be food for thought—and further self-appraisal. If you find a number of “Haven't Got It, But Can Get It” checkmarks, refer to the final two chapters of this Fieldbook. We have an array of resources for you that can help you “get it.”

Ready? Turn to Worksheet 10-1 and check the appropriate boxes as you and your partner assess your consulting qualities. We'll wait here until you finish the self-assessment and then we'll score and debrief the experience.

Now comes the moment of truth: scoring yourself. If you have rated (or been rated) as “Haven't Got It and Can't Get It” on any of qualities 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 14, or 18, consider these fatal flaws for performance consulting. Reflect on these responses. If they are truly accurate and you really “can't get it,” it is likely that performance consulting is not for you. Work with or support other performance professionals, or look for other interesting career activities.

If you rated (or were rated) “Haven't Got It But Can Get It” on those same items, keep reading this Fieldbook. Pay special attention to the final two chapters and the Additional Resources section. Seek a mentor to help you develop.

A checkmark in either of those two columns for any other item indicates some restriction in taking on a performance-consulting assignment alone. Work with a colleague to shore up your areas of weakness until you gain strength and confidence. In the meantime, play to your strengths. Notice how many checkmarks you do have in the first two columns. Exploit and continue to build on those qualities.

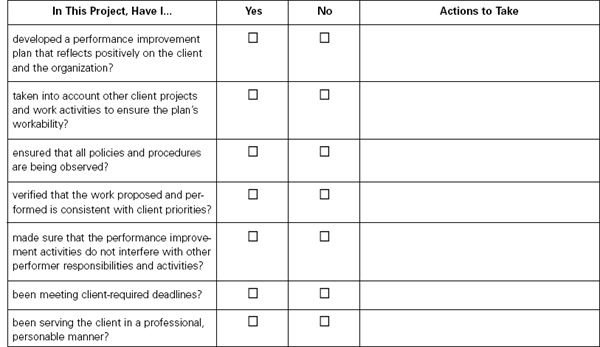

Am I Doing It Right?

As you move more deeply into the performance-consulting role and build your performance capabilities, it is wise to monitor your efforts with your clients to ensure that you are “doing it right.” Worksheet 10-2 can help you monitor your endeavors. Use it on a regular basis with each project. We have found it useful to sit down with the client and review each item either during a project or at the post-completion debriefing, or as a separate activity. This review invites dialogue, strengthens relationships, and yields useful feedback to help keep you on track.

The seven simple questions in the worksheet give a quick check on the quality and correctness of your work. They also offer the opportunity to make course corrections in your dealings with your client. Where you've answered “no” to a question, give some thought to appropriate corrective actions that you can take to improve your efforts. Remember that client feedback also gives you feed forward.

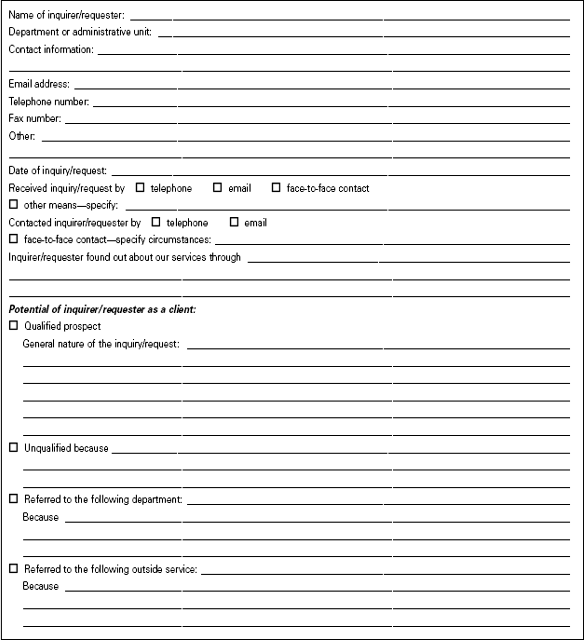

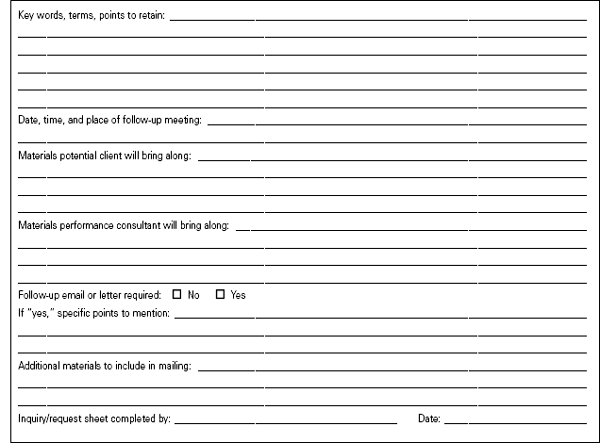

Handling Inquiries

As a training group, you probably receive inquiries and requests for services from a variety of people. You sort these requests into higher and lower priorities, decide what you can deliver, and follow up to respond in one way or another to the person who contacted you. As a WLP organization, however, you suddenly may find that you're inundated with a much broader array of inquiries or requests. It is essential that you and your team handle each of these inquiries systematically and professionally. Worksheet 10-3 can help you document each initial contact. Use it or a modified version every time you receive an inquiry or request for services.

Worksheet 10-2: Am I Doing It Right?

Instructions: Check “yes” or “no” or each of the following questions. Briefly describe actions you can take to correct a “no” score or to heighten your performance on “yes” items.

This tracking sheet not only helps you document inquiries and requests, but also forms a database that you and your WLP team can review. Over time, the nature of the inquiries or requests will help shape your team's orientation and will serve as a base for resource planning and budgeting.

Conducting the Initial Interview

You are preparing for the initial interview with the potential client. What should you do? What should you keep in mind? And what do you do during the interview? Are there specific actions to take after the interview? These are the questions this section of the Fieldbook addresses.

Worksheet 10-3: WLP Support Inquiry/Request Tracking Sheet

Instructions: Each time you receive an inquiry about or a request for your WLP support services, complete this worksheet. Keep it in your files.

The Purpose of the Initial Interview

As a performance consultant you have two main purposes for the interview:

- To find out as much as you can about the problem, need, or nature of the client's interest and concerns so that you can propose your involvement in the project.

- To sell yourself as the right person or team for the job (if that is the case).

You have to keep these two purposes uppermost in your mind. Everyone's time is valuable—including your own. The interview must be friendly, professional, and productive for both the client and you. Remember that most of your clients see you as the training person or group, so you have to reset their perceptions and expectations.

The Length of the Interview

The length of the interview should be commensurate with the potential of the project. Here are some recommendations:

![]() Before the interview, establish a reasonable length of time for meeting with the client. Stick to that allotment unless new developments occur during the interview itself.

Before the interview, establish a reasonable length of time for meeting with the client. Stick to that allotment unless new developments occur during the interview itself.

![]() For new projects, plan to spend one to two hours in a first encounter, unless this is going to be a large-scale project and you have many people to meet.

For new projects, plan to spend one to two hours in a first encounter, unless this is going to be a large-scale project and you have many people to meet.

![]() Don't lock yourself into a tight schedule of other activities on the day of the initial interview. Leave open time following the interview in case you and your client agree that more time is required. Ensure you have ample time after the meeting to review your notes privately and to clarify information gathered while it is still fresh in your mind.

Don't lock yourself into a tight schedule of other activities on the day of the initial interview. Leave open time following the interview in case you and your client agree that more time is required. Ensure you have ample time after the meeting to review your notes privately and to clarify information gathered while it is still fresh in your mind.

Your Appearance and Image

This is a touchy subject. How you dress, style your hair, or speak is a personal matter that has little to do with competence. But as a performance consultant, you know that appearance and image count…sometimes a lot. Here are some simple, straightforward guidelines to follow:

- First impressions count a great deal. Make the best impression you can.

- Dress as neatly as possible. A polished appearance gives the impression of a person concerned with order and detail.

- Dress in a manner similar to your potential client—usually one notch better—if you know how she or he dresses.

- Act in a professional but not pompous manner. Express competence, confidence, and caring, but not conceit. You are there to help your client as a partner. Create a climate of comfort—relaxed alertness.

- Be friendly, but not familiar. Try to understand your potential client—including aspirations and uncertainties with respect to the project. He or she is likely to tell you not only what the problem is, but also what the solution should be—probably training.

- Build empathy and show that you understand and respect his or her concerns—perhaps even share many of them. But focus on desired performance outcomes and not on the means to secure them.

- Above all, be yourself. If you have realistically assessed your qualities as a performance consultant and realized that you can handle the job, show who you and your team are and what you believe you can accomplish.

What You Should Learn from the Interview

At the interview you want to learn some very specific things:

- Precisely what problems require solving? (Training itself is not a problem.) What will the end result look like? Focus on desired performance.

- Exactly what are the client's expectations of you? What does she or he want you to do? You must work to shape those expectations.

- What will the client consider to be indicators or confirmation that the project objectives have been met?

- What particularly sensitive issues should you be aware of or watch for?

- What potential problems may arise? Does the project have a high probability of success? Where are the traps?

- Who is to be your main point of contact in the client's organization? Get her or his exact name, position title, and contact information. Often the person that you initially meet is not the person who'll coordinate and oversee the project.

- Is there a back-up contact person? Secure the same information for this person.

- In project terms, what authority does each contact person have?

- Is there a specific budget allocated for the project? If not, discuss how this will be determined.

- Is there a critical deadline by which the project must be completed?

In brief, you should come away from the interview with a clear understanding of what the client is looking for, who exactly represents the client, how much authority the client's representatives each have, what the size and scope of the project is (including the financial aspect), and what the client's expectations are concerning you.

What You Should Do at the Interview

The interview is more than a conversation. Here are some things to do—or avoid—during the initial interview:

- Take notes. Record essential information so that you can refer to it later when you brief others or when you write the proposal (and there should always be some form of written proposal, even if it is brief and more resembles a letter of understanding that includes a proposed work itinerary). If you don't understand a point during the interview, ask the client to repeat what was said or to give an example of what he or she is referring to. Seek confirmation that you understood, or get clarification if you did not. Ask for copies of company documents that may be helpful later and include these with your notes. Be sure to refer to them in your notes so you will remember where they apply.

- Don't give advice. Usually, you don't have enough information in the initial interview to make any recommendations. Stick to collecting information. This is critical. Be cause conscious, not solution focused. Remember front-end analysis.

- Listen very attentively. Display interest by nodding, taking notes, or asking questions. Occasionally, at convenient spots, ask if you can review major points and understandings to verify that you have heard and understood correctly. As you listen, interject brief probing questions to clarify matters (such as, “Could you give me an example of that kind of error?” “Approximately how many?” or “How often does this happen?”).

- Respond honestly to any questions the client asks about your ability to handle the project. Your client may be concerned about your availability to give the project priority because of your other commitments. You will want to reassure the client that performance consulting is a planned activity for you or your organization, and that you can give the project the attention it requires. (This assumes that what you have now learned about the project leads you to believe that you can handle it without conflict.) Your client also may be interested in learning more about your prior experience doing similar work. Be prepared to discuss your and your team's competencies and experience. If possible, have work samples that you can show.

- Share your needs and expectations. Feel comfortable sharing with the client the kinds of support you will require to complete the assignment successfully—such as an opportunity to meet senior managers; access to subject-matter experts, personnel records and company documents, and performers. The client must know what you need and what you expect. Let the client know the mode in which you operate—a collaborative approach involving the client organization throughout the project to ensure the greatest probability for successful implementation and maintenance. Remember: Collaboration and partnering are what performance consulting is all about.

At the end of the interview, ask the client to listen as you review what you have heard to verify that both of you are on the same wavelength. Check with your client to make sure that she or he has learned enough about you to make a decision about your appropriateness for the project. Review these key elements:

![]() what triggered the inquiry or request

what triggered the inquiry or request

![]() what the desired performance should look like

what the desired performance should look like

![]() the client's perception of current performance

the client's perception of current performance

![]() success criteria and credible metrics to demonstrate success. (Nowhere do you state what the solutions will be.)

success criteria and credible metrics to demonstrate success. (Nowhere do you state what the solutions will be.)

Closing the Interview

The interview is coming to an end. If you sense that the potential client wishes to engage your services, give some general information on how you feel you both should proceed next. Ask if he or she would like to go ahead with the project. Offer to send a statement of understanding or a proposal (which we deal with next) outlining tasks, timelines, and the budget if appropriate.

If the client is anxious to get started and makes a verbal commitment, state that you, too, want to go ahead with the project. Be careful about agreeing to timelines and costs. Be extremely tentative. Again, state that you will send correspondence confirming exactly what you can and will do, in what timeframe, and at what costs.

If you and your client decide that a proposal is required before any decision can be made, indicate that you will submit a brief but very specific proposal. Obtain the following clarifications:

![]() that you can call your contact person if you have any additional questions

that you can call your contact person if you have any additional questions

![]() exactly when the proposal should be submitted, and in what format

exactly when the proposal should be submitted, and in what format

![]() if there are specific pieces of information or documents that must be included with the proposal.

if there are specific pieces of information or documents that must be included with the proposal.

Shake hands (if appropriate) at the end of the interview. Thank the client for her or his time and interest in meeting with you, and be sure to leave a business card.

Get the letter of understanding or proposal in by the deadline. If no deadline was set, create one very close to the initial interview, and submit the document before your memory of key issues fades.

Speaking of proposals, we can now move on to the next section that deals with them.

Mastering the Proposal Process

From inquiry/request to interview to proposal—that's the normal sequence, although in performance consulting, you soon discover that very little occurs “normally.” Nevertheless, most projects, at some point, do call for a proposal in one form or another. How do you prepare one with maximum impact and minimum pain? That's what this section will help you accomplish.

What Is a Proposal and Why Is It Necessary?

A proposal is simply a written document that describes the performance-consulting assignment you are proposing to undertake. It applies equally to internal and external performance professionals. It spells out exactly what you will do if you and your team get the green light. The proposal includes the timeframe of your performance and the costs associated with your services.

After the initial interview in which the client and you discussed needs and generally defined the project, your next step takes the form of a proposal. This is almost always standard operating procedure. It finalizes the agreement by tying all the loose ends together and forms the basis for a contract. Whether you are an internal or an external consultant, a clear proposal is one of the hallmarks of a performance professional. If well written, it tends to increase the client's confidence in your ability to successfully produce.

What Do Proposals Look Like and What Should They Contain?

For the type of consulting you will most likely be doing, letter proposals are usually sufficient. A letter proposal is just like any other letter, except that it contains all the elements that lead to a clear understanding of the consulting assignment. In writing proposals, bear these tips in mind:

![]() Keep the structure of the proposal clear and logical. Headings that identify each major section help accomplish this objective.

Keep the structure of the proposal clear and logical. Headings that identify each major section help accomplish this objective.

![]() Use a professional but friendly style of writing.

Use a professional but friendly style of writing.

![]() Write your proposal to reflect your client-meeting conversation and the outcomes you arrived at together. (That is why we suggested copious note-taking at the initial meeting.) If new ideas (no matter how brilliant) come to you between the interview and the proposal submission, do not include them in your proposal without first testing them with your potential client. For example, if you decide that running a couple of focus groups with the client's employees would help facilitate the analysis you are proposing, don't just write these into the proposal. Check first. There may be very valid reasons, such as cost, time constraints, or confidentiality, that make this type of activity inappropriate.

Write your proposal to reflect your client-meeting conversation and the outcomes you arrived at together. (That is why we suggested copious note-taking at the initial meeting.) If new ideas (no matter how brilliant) come to you between the interview and the proposal submission, do not include them in your proposal without first testing them with your potential client. For example, if you decide that running a couple of focus groups with the client's employees would help facilitate the analysis you are proposing, don't just write these into the proposal. Check first. There may be very valid reasons, such as cost, time constraints, or confidentiality, that make this type of activity inappropriate.

![]() Check the proposal with the potential client before sending it. It is in everyone's best interest that the proposal be right on target even before you turn it in. It may be difficult or impossible to make changes later.

Check the proposal with the potential client before sending it. It is in everyone's best interest that the proposal be right on target even before you turn it in. It may be difficult or impossible to make changes later.

Your proposals will vary in length, depending on the project and what the client's expectations are. In general, proposals should contain the sections described below, but it is quite okay to delete one or more of the sections or add a heading or two, as your performance-consulting assignments dictate. Keep in mind that the following headers are elements that are found in most proposals. At least initially, follow this model quite closely.

An Opening

An opening is just a simple statement that you are writing to submit your ideas for the project under discussion. Refer to your client meeting and to the client's request for this proposal. A paragraph should suffice, although you may want to handle this in a very short cover letter and make the proposal a separate document.

Background and Understanding of Need

In this section you describe the background of the consulting situation, the nature of the problem or opportunity, your client's assumptions, and other general facts about the case. A single page is usually enough for this section.

The purpose of this part of the proposal is to reassure the client that you have a good understanding of the background of the situation and the need. If in the initial meeting you suspected there might be causes of the problem (other than those expressed by the client) that should be investigated or needs that have not been identified, it's important to address these. For example, if the client's analysis of the situation has led her or him to conclude that a training program is needed to overcome the problem, and you have reason to believe there may be other critical factors affecting the situation (perhaps unclear expectations, lack of feedback, lack of performance standards), your concerns should be expressed, with due caution. If the cause of the problem turns out to be different or greater than what your client suspected, the solution and implementation will have to vary as well. You have a responsibility to convince the client that these causes have to be explored before you write an official proposal. This means some form of front-end analysis is desirable. Remember: It is important to build and maintain a positive and open communication bond with your client from the outset.

Objectives

This half-page section, presented in bullet-point format, should be a precise statement of the objectives of the consulting engagement—what exactly your client will learn or receive as a result of your work.

Deliverables

You may be wondering what the deliverables are in this context. In brief, they are the finished products your client will receive. Here you describe—very succinctly—what the finished products will be (for example, documents, reports, training programs, job aids, policy and procedure manuals). These may be tentative at this point if you have not yet done front-end work.

Methodology

State what methods you will be using to accomplish the objectives. If several methods are possible, list them and explain why you selected the method you did. This is particularly important if your client is unfamiliar with performance consulting and expects design and development to start immediately.

There is a tendency in this section to use highly technical language. Avoid it unless your client also possesses technical expertise and vocabulary. Done in a concise manner—and that is the way it should be—a half-page to a full page should be sufficient.

Potential Problems

This section is optional but vital if you foresee potential problems—anything that could limit or detract from achieving the objectives. Documenting these here should prompt the client to reduce the possibility of their occurrence. It also serves as a safeguard if unavoidable problems cause delays, increased costs, or inability to do the assignment as originally described.

Schedule

This section may be as simple as stating a deadline date for the deliverables or as complex as a full-blown timeline detailing the project from commencement through follow-up. Use your own judgment based on the complexity of the assignment. When in doubt, include more details. Be careful with project management software. The outputs can sometimes confuse more than clarify.

Cost and Payment Information

Cost information should contain both fees (if your group bills clients) and expenses (if they apply). Payment information should include how much you expect to receive and when you would like to receive it. Bear in mind that most performance-consulting projects have a startup fee followed by payments at established intervals. Your payment schedule should be laid out so that the client can budget accordingly. Organizational guidelines prevail here.

Capabilities and Resources

In this section include a concise statement of your capabilities, previous clients, and similar problems you have handled. Be sure to include bios of yourself and others who likely will have key roles on the project. Make them short; a paragraph or two for each is fine. Also devote a paragraph in this section to your WLP organization. Share its key features and accomplishments with your potential client.

Authorization to Proceed

This is an optional section that enables you to convert a proposal into an agreement. It should include a statement indicating that signing below authorizes you and your team to proceed with the consulting assignment. Add space for the client's signature, title, and the date.

Exhibit 10-1 summarizes the key elements generally included in a performance-consulting proposal. Use its outline as a template for your initial proposal writing.

The first proposal you write will be tough. After that, it's a breeze. Why? Because some sections are standard, such as Capabilities and Resources. Other sections, such as schedules and cost and payment information, are “boilerplate”—you plug in relevant information that pertains to the project in question. Here are a few more points worth noting about the value and use of proposals:

![]() The proposal makes an excellent decision-making instrument. Because it states exactly what you will do, by when, and at what cost, it gives all the critical information required to make a decision about proceeding with a project. Proposals provide a written document that can be altered, if changing conditions warrant (such as new budgetary constraints or changes in priorities affecting timelines). A decision to accept a proposal in its original (or altered) state is a commitment to the project. It ties the client into the decision. When this is accomplished, everyone can move ahead.

The proposal makes an excellent decision-making instrument. Because it states exactly what you will do, by when, and at what cost, it gives all the critical information required to make a decision about proceeding with a project. Proposals provide a written document that can be altered, if changing conditions warrant (such as new budgetary constraints or changes in priorities affecting timelines). A decision to accept a proposal in its original (or altered) state is a commitment to the project. It ties the client into the decision. When this is accomplished, everyone can move ahead.

![]() The proposal is an excellent management tool when the decision has been reached and the commitment to proceed made clear. Both client and consultant benefit from the proposal documentation because it spells out milestones and metrics by which to monitor the project and manage the conditions it entails: Are work timelines being met? Are payments forthcoming on schedule? Is the agreed-to methodology being followed?

The proposal is an excellent management tool when the decision has been reached and the commitment to proceed made clear. Both client and consultant benefit from the proposal documentation because it spells out milestones and metrics by which to monitor the project and manage the conditions it entails: Are work timelines being met? Are payments forthcoming on schedule? Is the agreed-to methodology being followed?

Exhibit 10-1: Proposal Template

Opening

- Purpose of proposal

- Reference to client meeting(s) and request for proposal

- Outline of proposal contents

Background and Understanding of Need

- Background of the situation and nature of problem or opportunity

- Initial assumptions and general facts (from client)

- Findings from initial investigations (for example, front-end analysis)

- Issues, concerns and assumptions

- Initial conclusions

Objectives

- What will be accomplished, in specific terms:

—what will be done

—what results will be achieved

Deliverables

- Completed tangible artifacts:

—reports

—designs

—prototype materials

—final materials

—implementation plans

—evaluation plans

—other items as appropriate

Methodology

- List and description of all methods used to accomplish objectives:

—analysis methods

—facilitation methods

—management methods

—design and development methods

—implementation planning methods

—evaluation methods

—other methods as appropriate

Potential Problems

- Resource requirements

- Access to key people and data

- Security restrictions

- Budgets

- Conflicts in the organization

- Competing priorities

- Resistances

- Other issues as appropriate

Schedule

- Tasks

- Timelines

- Deliverables due dates

- Sign-offs

Cost and Payment Information

- Fees

- Expenses

- Payment schedule

- Special considerations and/or understandings

Capabilities and Resources

- Statement of WLP capabilities

- Client lists and testimonials

- Descriptions of similar projects and outcomes

- Names of project team members, their bios, and their assigned project roles

Authorization to proceed

- Brief statement converting proposal to commitment

- Spaces for authorization signatures, titles, and dates

Summary

- Review of key proposal elements

- Thanks for invitation to propose

Preparing Project Reports

One of the seemingly not-so-fun parts of performance consulting is the preparation and delivery of reports. But clients usually require them. If they are spending the money, time, and resources, at some point they will demand that reports be submitted. So let's tackle the topic of report writing. By the end of this discussion, you'll have useful tools and guidelines for producing those project reports on your own.

Some Advantages of Report Writing

Before being turned off by this aspect of performance consulting, examine some of the ways you benefit by preparing these reports:

![]() You get a chance to document what you've done. The end product of your consulting may appear insignificant (maybe just a new procedure for ordering vegetables), but your report can demonstrate how complex the task was, how ingenious the solution, and how valuable the organizational impact of your accomplishment.

You get a chance to document what you've done. The end product of your consulting may appear insignificant (maybe just a new procedure for ordering vegetables), but your report can demonstrate how complex the task was, how ingenious the solution, and how valuable the organizational impact of your accomplishment.

![]() You get your “day in court.” The report enables you to speak your mind and say, recommend, or forecast what you professionally believe to be true.

You get your “day in court.” The report enables you to speak your mind and say, recommend, or forecast what you professionally believe to be true.

![]() You produce a concrete document that you can reuse in a number of ways later—on other projects, in articles submitted to professional journals, or in conference presentations (with client approval, of course); in performance appraisals; and for coaching purposes.

You produce a concrete document that you can reuse in a number of ways later—on other projects, in articles submitted to professional journals, or in conference presentations (with client approval, of course); in performance appraisals; and for coaching purposes.

![]() Preparing the report prompts you to review and reflect on your work, and draw personal conclusions about how the project went and what you will do in the future.

Preparing the report prompts you to review and reflect on your work, and draw personal conclusions about how the project went and what you will do in the future.

Why Write a Report?

You write the project report for lots of reasons:

![]() to document what has been done to date in terms of what was proposed

to document what has been done to date in terms of what was proposed

![]() to inform the client of progress and/or problems

to inform the client of progress and/or problems

![]() to summarize information

to summarize information

![]() to lay out alternatives for decision making by the client organization

to lay out alternatives for decision making by the client organization

![]() to justify steps that were taken

to justify steps that were taken

![]() to describe, synthesize, and clarify accomplishments.

to describe, synthesize, and clarify accomplishments.

What Types of Reports Are Required?

These are the two types of reports that most usually are requested:

- Intermittent progress reports. The delivery dates for these reports and their volume and content should be specified in the proposal or in a contract.

- Final reports. These summarize what occurred from the start of the project to its completion. They usually end with conclusions and recommendations for future projects, project maintenance, or organizational action.

Other reports you may find yourself working on are

![]() technical reports—usually stating the problem, giving the background, and briefly laying out the planned methodology. They go on to create a blueprint of technical details (with justification) where necessary, and give information and a plan that relevant client organization personnel or contractors can understand and use.

technical reports—usually stating the problem, giving the background, and briefly laying out the planned methodology. They go on to create a blueprint of technical details (with justification) where necessary, and give information and a plan that relevant client organization personnel or contractors can understand and use.

![]() survey or research reports, which open with a problem or question statement, lay out background information, describe the methodology (usually with sample forms, questionnaires, and interview protocols in the appendixes), provide the data analysis, detail the results and possible interpretations of the results, and end with conclusions and recommendations.

survey or research reports, which open with a problem or question statement, lay out background information, describe the methodology (usually with sample forms, questionnaires, and interview protocols in the appendixes), provide the data analysis, detail the results and possible interpretations of the results, and end with conclusions and recommendations.

![]() focus group or interview reports, which generally include a statement of the problem, an understanding (or background) of the problem, methodology and objectives, a list of meetings, the names of people present or interviewed (unless anonymity is called for), a description of what came out of the meetings or interviews, and your conclusions and recommendations. (Meeting or interview protocols usually go in an appendix.)

focus group or interview reports, which generally include a statement of the problem, an understanding (or background) of the problem, methodology and objectives, a list of meetings, the names of people present or interviewed (unless anonymity is called for), a description of what came out of the meetings or interviews, and your conclusions and recommendations. (Meeting or interview protocols usually go in an appendix.)

![]() literature-review reports, which are fairly rare, include an introduction to major questions requiring answers from the relevant literature, a rationale for asking these questions, a list of relevant sources, the literature review methodology, the review itself (with partial conclusions along the way), and overall conclusions to be drawn from the literature. If required, the report may make recommendations. It should contain an annotated bibliography of all reference materials. Including copies of critical articles or sections of reports in an appendix is useful.

literature-review reports, which are fairly rare, include an introduction to major questions requiring answers from the relevant literature, a rationale for asking these questions, a list of relevant sources, the literature review methodology, the review itself (with partial conclusions along the way), and overall conclusions to be drawn from the literature. If required, the report may make recommendations. It should contain an annotated bibliography of all reference materials. Including copies of critical articles or sections of reports in an appendix is useful.

![]() financial reports, which generally are very brief, detail expenses with respect to budgetary allocations. A financial or accounting person must work with you in preparing these reports, both the periodic and the final ones. The client often has a specific format or accounting forms that you must use. Get these from the client and conform to them 100 percent.

financial reports, which generally are very brief, detail expenses with respect to budgetary allocations. A financial or accounting person must work with you in preparing these reports, both the periodic and the final ones. The client often has a specific format or accounting forms that you must use. Get these from the client and conform to them 100 percent.

Who Writes the Reports?

If you are the primary performance consultant and “doer” on the project, you generally are responsible for writing the reports. You can, however, ask for assistance or even assign other people to write specific sections, such as

![]() the client or members of the client organization to provide internal data, examples, and documents

the client or members of the client organization to provide internal data, examples, and documents

![]() WLP colleagues to write a brief piece on an aspect of the project they know best

WLP colleagues to write a brief piece on an aspect of the project they know best

![]() certain administrative units in your organization to provide statistics, policies, equipment numbers and prices, and the like

certain administrative units in your organization to provide statistics, policies, equipment numbers and prices, and the like

![]() other specialists or assistants working with you on the project and knowledgeable about certain aspects of it.

other specialists or assistants working with you on the project and knowledgeable about certain aspects of it.

Don't be shy about asking various people to contribute. But also know that you will have to edit what they write and pull it all together into a consistent style and format.

How Should the Report Be Written?

Here are a few tips about the style and appearance of your reports:

![]() Keep as your motto “less is more.” Be as brief as possible without leaving out important information.

Keep as your motto “less is more.” Be as brief as possible without leaving out important information.

![]() Go for clarity more than for literary style. Use clear, clean, short active sentences that say what has to be said.

Go for clarity more than for literary style. Use clear, clean, short active sentences that say what has to be said.

![]() Omit needless words. Get someone to read your report and cross out superfluous words.

Omit needless words. Get someone to read your report and cross out superfluous words.

![]() Be specific. No vague stuff. “This section presents 14 sample menus for people with diabetes,” not, “In this section we attempt to offer a variety of menus for the diabetic patient.”

Be specific. No vague stuff. “This section presents 14 sample menus for people with diabetes,” not, “In this section we attempt to offer a variety of menus for the diabetic patient.”

![]() Put the guts of your report into the verbs—make it action oriented. Use fewer adjectives and adverbs (such as “In the training seminar, participants role-played management and administrative personnel,” instead of “In the training seminar, participants took the interesting roles of management…”).

Put the guts of your report into the verbs—make it action oriented. Use fewer adjectives and adverbs (such as “In the training seminar, participants role-played management and administrative personnel,” instead of “In the training seminar, participants took the interesting roles of management…”).

![]() Avoid “fancy” words or technical jargon that only look like they are trying to impress.

Avoid “fancy” words or technical jargon that only look like they are trying to impress.

![]() Write in the active voice. “This project produced 12 output specification sheets,” rather than “Twelve output specification sheets were produced by this project.”

Write in the active voice. “This project produced 12 output specification sheets,” rather than “Twelve output specification sheets were produced by this project.”

![]() Keep paragraphs short.

Keep paragraphs short.

![]() Use graphs, charts, tables, and pictures wherever possible, and comment on them briefly.

Use graphs, charts, tables, and pictures wherever possible, and comment on them briefly.

![]() Get an editor to revise your report for

Get an editor to revise your report for

• consistency and style

• grammar, spelling, and punctuation

• clarity

• unnecessary verbiage

• overall professionalism and comprehensibility for the intended reader(s)

What Should the Report Include?

Each report has its own set of requirements. For most interim reports, the format in Exhibit 10-2 works well.

Interim reports have one purpose: to keep the client informed and up-to-date. Keep them short. Unless you have a long and complex project, your interim reports should run from three to 10 pages plus appendixes.

Final or major reports are a different matter. According to the size and scope of the project, a major report could run from a few pages to several hundred. Most performance-consulting reports, when required, are brief. An analysis of our last 20 projects shows that we had

![]() one requiring four interim reports and one final report

one requiring four interim reports and one final report

![]() five requiring final reports of no more than 25 pages

five requiring final reports of no more than 25 pages

![]() three requiring a large final report that included all accomplishments—approximately 250 pages

three requiring a large final report that included all accomplishments—approximately 250 pages

![]() 11 requiring no final reports, but for which we produced assorted memos, summary documents of varying lengths, and products.

11 requiring no final reports, but for which we produced assorted memos, summary documents of varying lengths, and products.

Exhibit 10-2: Interim Report Template

Title page

- Name of project

- Name of client organization

- Author(s) and affiliation/s

- Period covered by report

- Report number (#1, #2,…)

- Date of report submission

Table of Contents(for reports of 15 pages or more)

Introduction

- Outline and/or specification of objectives worked on during reported time period

- Actions taken (in bullet-point form)

Accomplishments(in bullet-point form)

Concerns

- Project

- Personnel

Financial Report(use client formats and guidelines)

Recommendations

Appendixes

- Drafts of materials or reports

- Sample plans

- Meeting minutes

- Useful documents

Exhibit 10-3 is a sample template outline for a performance-consulting final report. It can be applied or easily adapted for most projects.

As to appendixes, the general rule is, if an item breaks the flow of the report and cannot be placed in a succinct table or figure, place it in an appendix. Often, appendixes are more voluminous than the body of the report.

In closing our discussion of final reports, we want to remind you that their dual purpose is to document what you and your team accomplished and to inform the client and stakeholders as succinctly but specifically as possible what they received for the money, resources, time, and effort invested.

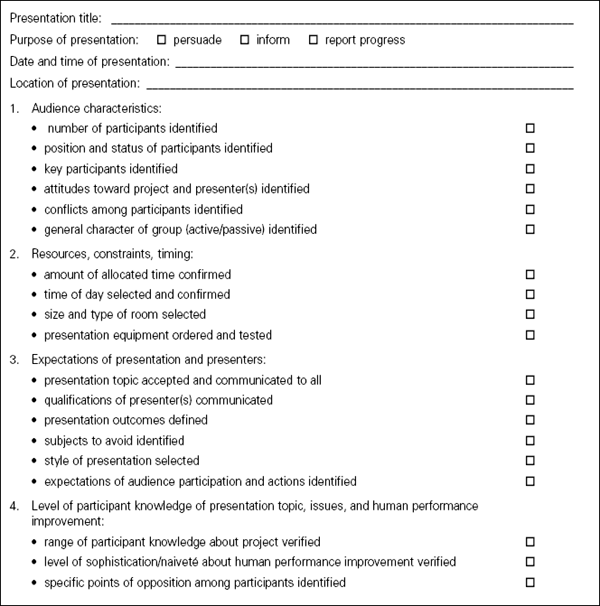

Making Presentations

A major part of performance consulting is making presentations. Why? For almost the same reasons as writing reports: to document; to inform; to summarize; to lay out alternatives; to build support; to justify, report, synthesize, and clarify; and to inspire, convince, and sell the human performance improvement approach.

Two critical differences between reports and presentations are these:

- A report stands alone and depends entirely on its content. A presentation not only depends on its content, but also on you and the way you present that content.

- A report may or may not be entirely read or alternatively studied. You have no control over that. In a presentation you have greater control over your clients' and others' attention.

As a performance consultant your three main purposes for making live or virtual oral presentations are

- to persuade: convince your listeners to examine the data, draw conclusions similar to yours, avoid focusing on means and fix attention on ends, and invite them to act as required to achieve desired performance outcomes

- to inform: give decision makers or project stakeholders the information required to teach them something that they ought to know

- to report progress or lack of it: bring key players up-to-date so they don't encounter surprises.

Sometimes more than one purpose guides a presentation. Regardless of purpose, use the checklist in Worksheet 10-4 for all of your presentations. It helps you build a portrait of your audience, decide on your timing, and verify the environment before creating your presentation.

Generally, presentations in the human performance improvement domain contain four main sections. Variations abound, of course, but if you and your WLP team are relatively new to the field, the presentation plan contained in Exhibit 10-4 may prove helpful.

Exhibit 10-3: Final Report Template

Title page

- Name of project

- Name of client organization

- Author(s) and affiliation(s)

- Date of submission

- Note at bottom of page as follows: “Final report submitted in accordance with the requirements of contract #ABC1234-1, issued July X, 2XXX.”

Acknowledgments Page

- Recognition of those who contributed to the project

- Thanks to individuals, groups who supported the project

Table of contents(for reports of 15 pages or more)

Executive Summary(2-3 pages for reports of 20 pages or more)

- Key points from each report section

- Clear, concise list of conclusions and recommendations

Introduction(1-3 pages)

- Project need

- Project purpose

- History and context of performance improvement situation

- Critical events that triggered the project

- Important decisions that stimulated the project

Statement of the Problem or Overall Project Objective

- Problem to be solved or nature of the project

- Rationale for performance-consulting approach

- Useful background information

Project Methodology

- Front-end analysis and rationale

- Intervention selection and rationale

- Intervention development and rationale

- Evaluation, monitoring, and maintenance with rationale

Project Objectives(cover the following for each objective)

- The objective itself

- Activities

- Deliverables/products

- Results

- Conclusions

For this section, draw heavily from interim reports.

Project Conclusions

- Accomplishments

- What was not accomplished

- Overall project conclusions with explanations

Recommendations

- Further actions

- Further decisions

- Time and action calendar (if appropriate)

Appendixes

- Protocols, policies, plans, transcripts of interviews, detailed analyses, lengthy evaluation tables

- Sample materials produced

- Financial reports

Worksheet 10-4: Presentation Checklist

Instructions: Use this checklist to prepare for your presentation. Check off each task as you complete it.

Presentations are both challenges and opportunities for you as a performance consultant. They give you the opportunity to display what you have done, can do, and believe in as a performance professional. Well-organized and -delivered presentations can do a great deal to make your performance-consulting projects flow more smoothly as your reputation and that of your WLP team grows.

![]()

An Activity for Your WLP Team

Take the content of this entire chapter to your team. Review all key points and study the worksheets and exhibits. Select and, if needed, adapt all those that appear valuable to exploit. Make decisions on what to do and how to act moving forward.

Exhibit 10-4: Presentation Plan

Opening(brief, clear, and attention getting)

- Provocative question or strong affirmation

- Empathy builder to draw the participants toward you

- Statement of purpose with rationale

- Statement of specific objectives—expectations of what the participants will accomplish as a result of the presentation

Body(moves participants along to the attainment of objectives)

- Presentation of each objective, including

—clear statement

—clear, direct structure

—clear statistics, examples, and anecdotes to highlight and support key points

—visuals, as appropriate, to clarify, support, and lead participants along

—clear, logical arguments, conveyed with conviction

Summary/Conclusion(the “finale” that helps participants draw appropriate conclusions and make desired decisions)

- Review of key points

- Presentation of conclusions (with crispness and conviction)

- Emphasis on urgency and importance of conclusions

- Recommended actions

- Summary of action requirements and a firm, credible, even dramatic (if appropriate), close

Questions and Answers(to explain and defend—but don't be defensive)

- Crisp, brief responses, in order, to questions posed (anticipated and prepared for in advance as possible)

- Response to questions within presentation timeframe

- Avoidance of debate

- Respectful responses to questions, regardless of quantity or tone of question

- Firm, specific responses

- Explanation of follow-up for questions that cannot be answered immediately

Chapter Summary

What a large chapter, and what a vast subject! Becoming a performance consultant is far more challenging than taking training orders. It's significantly more strategic. It makes greater demands on you. It also offers immense rewards for both you and your organization. In this chapter

![]() you defined what it means to be a consultant in WLP.

you defined what it means to be a consultant in WLP.

![]() you reviewed the value add that you bring to your clients and organization in your performance consulting role.

you reviewed the value add that you bring to your clients and organization in your performance consulting role.

![]() you revisited the performance-consulting competencies and critical characteristics from Training Ain't Performance, and pinpointed how each of these adds value for all stakeholders.

you revisited the performance-consulting competencies and critical characteristics from Training Ain't Performance, and pinpointed how each of these adds value for all stakeholders.

![]() you assessed your performance-consulting potential and drew conclusions about yourself.

you assessed your performance-consulting potential and drew conclusions about yourself.

![]() you reviewed a worksheet to help you determine whether you are carrying out your performance-consulting role correctly.

you reviewed a worksheet to help you determine whether you are carrying out your performance-consulting role correctly.

![]() you gained a job aid to help you handle inquiries and requests for your WLP services.

you gained a job aid to help you handle inquiries and requests for your WLP services.

![]() you examined a series of guidelines and tools to assist you in handling initial client interviews, writing proposals, preparing reports, and making presentations.

you examined a series of guidelines and tools to assist you in handling initial client interviews, writing proposals, preparing reports, and making presentations.

Although this appears so demanding, it really is a natural extension of what you currently do. Yes, it requires stretching and growing, but it's enormously worthwhile for you and your organization. Both of you benefit. The payoff will endure long into the future.

While all of this is still fresh in your mind, turn to the next chapter. It focuses on the performance consultant-client relationship. It's the companion chapter to this one.