CHAPTER TWO

Discharge of Indebtedness

§ 2.1 Introduction

§ 2.2 Discharge of Indebtedness Income

§ 2.3 Determination of Discharge of Indebtedness Income

(a) What Is Discharge of Indebtedness Income?

(i) In General

(ii) Discharge of Recourse and Nonrecourse Debt

(iii) Transfer or Repurchase of Debt

(iv) Income Other than Discharge of Indebtedness

(v) No Income

(vi) Contested Liability Doctrine and Unenforceable Debt

(b) Is the Obligation Indebtedness?

(c) Who Is the Debtor?

(d) When Does Discharge of Indebtedness Income Occur?

§ 2.4 Section 108(e) Additions to Discharge of Indebtedness Income

(a) Debt Acquired by Related Party: Section 108(e)(4)

(i) Related Party

(ii) Acquisition by a Related Party

(A) Direct Acquisition

(B) Indirect Acquisition

(iii) DOI Income for a Related Party Acquisition

(b) Indebtedness Contributed to Capital: Section 108(e)(6)

(i) Allocation between Principal and Interest

(ii) Withholding Requirement

(iii) Accounting Method Differences

(c) Stock for Debt: Section 108(e)(8)

(i) Background

(ii) Overlap with Capital-Contribution Rule

(A) Meaningless Gesture Doctrine

(B) Bifurcation

(C) Advantages and Disadvantages

(d) Debt for Debt: Section 108(e)(10)

(i) Background

(ii) Publicly Traded Debt versus Non–Publicly Traded Debt

(iii) Significant Modification of a Debt Instrument

(A) Modification

(B) Significant Modification

(C) Multiple Modifications

(D) Disregarded Entities

§ 2.5 Section 108(e) Subtractions from Discharge of Indebtedness Income

(a) Otherwise Deductible Debts: Section 108(e)(2)

(b) Purchase Price Reduction: Section 108(e)(5)

(i) Creditor That Is Not Seller

(ii) Solvent Debtor

(c) Summary

§ 2.6 Discharge of Indebtedness Income Exclusions

(a) Title 11 Exclusion

(b) Insolvency Exclusion

(i) Liabilities

(ii) Assets

(iii) Timing

(c) Qualified Farm Indebtedness Exclusion

(d) Qualified Real Property Business Indebtedness Exclusion

(e) Tax Benefit Rule

§ 2.7 Consequences of Qualifying for Section 108(a) Exclusions

(a) Attribute Reduction

(b) Net Operating Loss Reduction

(i) Net Operating Loss Reduction and Carrybacks

(ii) Net Operating Loss Carryover Calculation

(iii) Interaction with Section 382(l)(5)

(c) Credit Carryover Issues

(d) Basis Reduction

(i) Basis Reduction Election

(A) Election Procedures

(B) Basis Adjustment of Individual’s Estate

(ii) Basis Reduction Rules

(A) Title 11 and Insolvency

(B) Basis Reduction Election

(C) Qualified Farm Indebtedness

(D) Qualified Real Property Business Indebtedness

(E) Depreciable Property Held by Partnership

(F) Depreciable Property Held by Corporation

(G) Multiple Debt Discharges

(H) Recapture Provisions

(iii) Tax-Free Asset Transfers

(iv) Comparison of Attribute Reduction and Basis Reduction Elections 94>

(e) Alternative Minimum Taxable Income

§ 2.8 Section 108(i) Deferral and Ratable Inclusion of DOI from Business Indebtedness Discharged by the Reacquisition of a Debt Instrument

(a) Overview

(b) Statutory Provisions

(i) Defined Terms

(ii) Effect on OID

(iii) Making the Election

(iv) Acceleration of Deferral

(v) Interplay with Other Section 108 Exclusions

(c) Revenue Procedure 2009-37

(i) Applicable Debt Instrument

(ii) Reacquisition and Acquisition

(iii) Partial Elections

(iv) Consolidated Groups and Foreign Entities

(v) Earnings and Profits

(vi) Protective Election

(vii) Annual Statement and 12-Month Extension

(d) Treasury Decision 9497 (Temporary Regulation)

(i) Mandatory Acceleration Events for Deferred DOI Income

(A) Net Value Acceleration Rule

(B) Changes in Tax Status

(C) Cessation of Existence

(D) Bankruptcy

(ii) Earnings and Profits

(iii) Intercompany Obligations

(iv) Deemed Debt-for-Debt Exchanges

(v) Deferred OID Deductions

(vi) Effective/Applicability Dates

(e) Treasury Decision 9498 (Temporary Regulation)

(f) Planning Points

§ 2.9 Use of Property to Cancel Debt

(a) Transfer of Property in Satisfaction of Indebtedness

(i) Transfer of Property in Satisfaction of Nonrecourse Debt

(A) Gain from the Property Transfer

(B) Loss on the Property Transfer

(ii) Transfer of Property in Satisfaction of Recourse Debt

(A) Gain on the Property Transfer

(B) Loss on the Property Transfer

(iii) Character of the Gain or Loss

(b) Discharge of Nonrecourse Debt

(c) Foreclosure

(d) Abandonment

2.10 Consolidated Tax Return Treatment

(a) Consolidated Return Issues

(i) Election to Treat Stock of a Member as Depreciable Property

(ii) Single-Entity versus Separate-Member Approach for Attribute Reduction

(A) Temporary and Final Regulations

(B) Prior to the Temporary Regulations

(iii) DOI/Stock Basis Adjustments/ELAs

(iv) Intercompany Obligation Rules

(A) Intercompany Obligation Regulations: General Rules and Application to Intragroup and Outbound Transactions

(B) Intercompany Obligation Regulations: Application to Inbound Transactions

§ 2.11 Discharge of Indebtedness Reporting Requirements

(a) Information Reporting Requirements for Creditors

(i) Applicable Entity

(ii) Amount Reported

(iii) Identifiable Event

(iv) Exceptions

(v) Multiple Debtors

(vi) Multiple Creditors

(vii) October 2008 Final and Temporary Regulations

(b) Filing Requirements for Debtors

§ 2.1 INTRODUCTION

One major source of income in most insolvency and bankruptcy proceedings is debt cancellation. Section 61 of the Internal Revenue Code (I.R.C.) lists discharge of indebtedness as one item subject to tax, and the Treasury Regulations (Treas. Reg.), at section 1.61-12(a), provide that the discharge of indebtedness, in whole or in part, may result in the realization of income. Prior to the codification of the general principle that debt cancellation is income, debt cancellation was deemed to produce income under the Supreme Court’s decision in United States v. Kirby Lumber Co.1 The Supreme Court held that the debtor realized income under two interrelated theories. First, the debtor realized an accession to income due to the transaction. Second, under a freeing-of-the-assets theory, assets previously offset by liabilities were “freed” by the transaction.

Several exceptions to this basic policy have evolved since the Kirby Lumber decision. For example, a cancellation of indebtedness may be more appropriately characterized as a contribution to capital, distribution, gift, or purchase price adjustment. The Bankruptcy Tax Act of 1980 codified some of these exceptions, rejected or conditioned the availability of others, and introduced additional provisions addressing whether and to what extent particular transactions give rise to discharge of indebtedness income. Before discussing the current discharge of indebtedness provisions, the manner in which debt cancellation was handled in prior law will be summarized.

§ 2.2 DISCHARGE OF INDEBTEDNESS INCOME

The treatment of income from the discharge of indebtedness was of particular interest to the drafters of the Bankruptcy Tax Act of 1980. Their chief concern was that taxation of such income would reduce the amount available to satisfy the claims of creditors who, in most cases, were already receiving less than 100 percent of their claims.

The Bankruptcy Tax Act amended I.R.C. section 108 to apply to bankruptcy proceedings as well as to out-of-court settlements. Prior to this amendment, I.R.C. section 108 applied only to discharge of indebtedness out of court. I.R.C. section 108(a), as amended by the Tax Reform Act of 19862 and subsequent statutory amendments, provides that income from discharge of debt can be excluded from gross income under any one of the following conditions:3

- The discharge occurs in a title 11 case.4

- The discharge occurs when the taxpayer is insolvent.5

- The indebtedness discharged is qualified farm indebtedness.6

- The indebtedness discharged is qualified real property business indebtedness.7

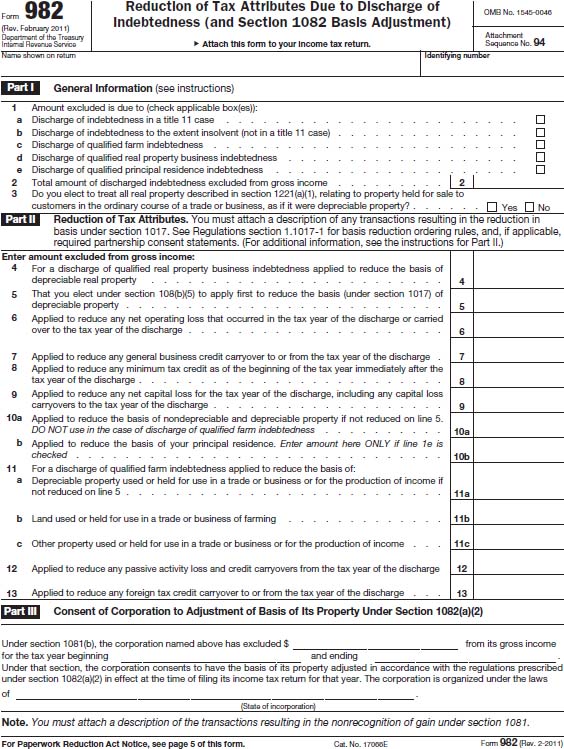

Exclusion of income under these provisions must be accompanied by a reduction of tax attributes. Attribute reduction and other consequences of qualifying for income exclusion under I.R.C. section 108(a) are discussed in detail later in this chapter (§ 2.7(a)–(d)).

Before income can be excluded under I.R.C. section 108(a), it must be properly characterized as income from the discharge of indebtedness under I.R.C. section 61(a)(12) (DOI income8), and not operating income or gain on an exchange. Numerous cases and rulings have addressed this issue. The Bankruptcy Tax Act of 1980 codified (and/or altered) some judicial approaches to whether particular transactions give rise to DOI income. Although this codification should logically have been added to I.R.C. section 61(a), it was instead added to I.R.C. section 108(e).

The remainder of this chapter discusses whether particular income is DOI income, focusing first on representative cases and rulings under I.R.C. section 61(a)(12) and then on the provisions of I.R.C. section 108(e) that explicitly expand and contract the scope of DOI income. Having determined which income is DOI income, the chapter then turns to whether that income is excluded from gross income under one of four exclusions: title 11 cases, insolvency, qualified farm indebtedness, and qualified real property business indebtedness. The discussion then addresses the consequences of coming within the purview of I.R.C. section 108(a). The chapter considers the unique issues raised by the use of mortgaged property to cancel debts and addresses specific rules that are provided in the consolidated return regulations. If the consolidated return regulations apply, the tax consequences of a debt cancellation may be different from the tax consequences initially discussed in the sections to follow. Finally, the chapter addresses specific filing requirements.

§ 2.3 DETERMINATION OF DISCHARGE OF INDEBTEDNESS INCOME

(a) What Is Discharge of Indebtedness Income?

I.R.C. section 61(a)(12) includes in gross income “income from the discharge of indebtedness.” The basic concept of DOI income may be illustrated by example. A debtor borrows $100 from a creditor who later accepts $60 from the debtor in complete satisfaction of the $100 debt. In this simple example, the debtor has $40 of DOI income. Before discussing the ramifications of DOI income, the threshold issue is whether DOI income exists in a particular transaction. As demonstrated by cases and rulings, one of three characterizations generally prevails: DOI income, income other than DOI income, or no income.

(i) In General

DOI income arises when a creditor releases a debtor from an obligation that was incurred at the outset of the debtor-creditor relationship. In United States v. Centennial Savings Bank FSB,9 the Supreme Court held that the imposition of an early withdrawal penalty on certificates of deposit (CDs) was not the discharge of an obligation to repay. When customers deposited money and the bank issued CDs, debtor-creditor relationships were created between the bank and the depositors. Like most CDs, the terms and conditions of the instruments included an interest rate, maturity date, and early withdrawal penalty.

Focusing on the meaning of “discharge,” the Supreme Court found that “discharge of indebtedness” conveys the forgiveness of, or the release from, an obligation to repay. A depositor who cashed in a CD before the maturity date and paid the early withdrawal penalty did not forgive or release any obligation of the bank. By paying principal and interest, less the penalty, the bank paid exactly what it was obligated to pay under the terms of the CD agreement. Although the bank has income equal to the amount of the penalty, the income is not from the release of an obligation incurred by the bank at the outset of its debtor-creditor relationship with the depositor. The Supreme Court held that to determine whether the debtor has realized DOI income, “it is necessary to look at both the end result of the transaction and the repayment terms agreed to by the parties at the outset of the debtor-creditor relationship.”10

The standard used in Centennial Savings Bank was applied to a different transaction, but had the same result, in Philip Morris Inc. v. Commissioner.11 Philip Morris borrowed an amount of foreign currency from a bank. Before Philip Morris repaid the loan, the value of the dollar increased relative to the borrowed foreign currency. When Philip Morris paid back the amount of foreign currency it had borrowed, it used a stronger dollar (i.e., it converted fewer dollars into the foreign currency) to satisfy its obligations.

Philip Morris did realize a “foreign exchange gain” on the repayment of the foreign currency loan, but the gain was not DOI income. The Tax Court noted that “the teaching of Centennial Savings is clear, namely that the discharge of an indebtedness may be an occasion for the realization of income but, unless there is a cancellation or forgiveness of a portion of the indebtedness not reflected in the terms of the indebtedness, such income is not discharge of indebtedness income.”12 Because Philip Morris’s foreign exchange gain resulted from favorable conditions in the currency market, rather than a forgiveness or release of its obligations under the foreign currency loan, DOI income did not exist.13

Philip Morris is representative of the far-reaching impact of Centennial Savings. Before Centennial Savings, the courts had generally held that foreign exchange gain was DOI income. One example of this was Kentucky & Indiana Terminal Railroad Co. v. United States.14 The Philip Morris decision specifically notes that Centennial Savings undermines the continued viability of Kentucky & Indiana Terminal Railroad Co.15

(ii) Discharge of Recourse and Nonrecourse Debt

The cancellation of either recourse or nonrecourse debt may trigger DOI income.16 In basic terms, debt is recourse if the debtor is personally liable for the amount due; debt is nonrecourse if the debtor is not personally liable for the debt (i.e., the creditor can look only to the property securing the debt if the debtor defaults).

The next cases involve the satisfaction and assumption of mortgages on real property. In re Collum17 is another example of what is not DOI income based on Centennial Savings. Collum involves the sale of real property that is subject to a recourse mortgage (i.e., the mortgagor is personally liable for the debt). The Collums sold the property to a corporation that assumed the mortgage; however, the couple was not released from liability. The court held that gain, not DOI income, was realized on the sale of the property.18

The extant cases discussed so far demonstrate what is not DOI income. The next decision is an example of what is DOI income—a discount received on the prepayment of a recourse mortgage. Generally, satisfaction of a mortgage on a taxpayer’s residence for less than the amount due creates DOI income.19 Michaels v. Commissioner20 involves the Michaels’ sale of their primary residence. In connection with the sale of the house, the mortgage balance was discounted by 25 percent. The Michaels included the discount as part of the capital gain on the sale, which was deferred under I.R.C. section 1034 when the couple purchased a more expensive residence. The Michaels argued unsuccessfully that, because the mortgage payment was an integral part of the sale of the residence and because the buyer’s funds were used to prepay the mortgage, the discount should be taken into account in calculating the gain realized, but not recognized due to I.R.C. section 1034. The Tax Court held that the discount was income from the discharge of indebtedness separate from the sale of the property.

The Supreme Court issued Centennial Savings after the Tax Court issued Michaels, so it is possible that the subsequent decision undermines the precedential value of Michaels, as in Kentucky & Indiana Terminal Railroad discussed in § 2.3(a)(i). This is not likely, however, because the facts of Michaels do not indicate that the discount was part of the terms of the mortgage.

(iii) Transfer or Repurchase of Debt

DOI income may be realized when the debtor repurchases outstanding debt at a bargain price. This occurred in the 1931 landmark United States v. Kirby Lumber Co.21 decision. The Supreme Court held that the debtor realized DOI income under two interrelated theories. First, the debtor realized an accession to income due to the transaction. Second, under a freeing-of-the-assets theory, assets previously offset by liabilities were “freed” by the transaction.

The calculation of income on the repurchase of debt is currently addressed in Treas. Reg. section 1.61-12(c)(2)(ii), which provides that “[a]n issuer realizes income from the discharge of indebtedness upon the repurchase of a debt instrument for an amount less than its adjusted issue price (within the meaning of Treas. Reg. section 1.1275-1(b)). The amount of discharge of indebtedness income is equal to the excess of the adjusted issue price over the repurchase price.”22

The reference to the original issue discount provisions (Treas. Reg. section 1.1275-1(b)) for the determination of adjusted issue price was added to the regulations in 1998.23 Interestingly, this amendment was a stealth regulatory reversal of United States Steel Corp. v. United States24 and Fashion Park, Inc. v. Commissioner.25 Both cases involved fact patterns that are similar to the following scenario: Assume that a corporation issued preferred stock for $100, and the value of the preferred stock increases to $165. The corporation redeems the preferred stock with $165 in debt. The corporation later repurchases the debt for $120.

In Fashion Park, a 1954 decision, the Tax Court relied on Kirby Lumber and Rail Joint Co. v. Commissioner26 to hold that the corporation did not have any income when it repurchased debt for less than its face value because there was no increase in the corporation’s assets.

A 1988 case, United States Steel, involved a fact pattern and result similar to Fashion Park—no DOI income based on the freeing-of-assets theory. When United States Steel was decided, the then-current regulations generally provided that DOI income from the repurchase of debt was equal to the excess of the issue price (without reference to the original issue discount rules) over the repurchase price.27 The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) argued that the issue price of the debt was the market value of the preferred stock when the debt was issued ($165 in the example), resulting in DOI income equal to the issue price less the repurchase price ($165 – $120 = $45). The Federal Circuit was not persuaded by this argument and held that the issue price of the debt was the amount the corporation received when it originally issued the preferred stock for $100, noting that it was not necessary to determine issue price by reference to the original issue discount rules. Consequently, the Federal Circuit found no DOI income on the debt repurchase.

United States Steel would not have the same outcome under the current regulations; rather, the position the IRS had taken in that case would prevail and the debtor would have DOI income. Under Treas. Reg. section 1.61-12(c)(2)(ii), the calculation of the issue price is determined under the original issue discount rules, which results in $45 DOI income ($165 issue price less $120 repurchase price). This 1998 change was made as part of a larger regulatory package without mention of the United States Steel decision in the accompanying preamble.

It appears that the amendment made to Treas. Reg. section 1.16-12(c)(2)(ii) was made by Treasury to overturn the United States Steel decision. The exact breadth of the amendment is unclear. One could argue that the change could apply to result in DOI in fact patterns such as those in cases like Centennial Savings (discussed in § 2.3(a)(i)) and Rail Joint.28 The better view, however, is that regulatory amendments should not have the effect of overturning precedents such as Centennial Savings and Rail Joint that are cornerstone cases in the DOI area.

The Tax Court’s analysis in a more recent DOI case is worthy of discussion but should be viewed circumspectly in light of its reliance on a regulatory regime that applied to the year at issue but that was, as discussed, subsequently amended. Although Hahn v. Commissioner29 represents a perfectly fine decision with respect to its particular facts, one should be careful in applying certain statements in the decision to other fact patterns.30

The facts of the Hahn decision are simple. Gilbert Hahn borrowed money from a bank in exchange for his promissory note. When he subsequently satisfied the debt at a discount, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), which had taken over the receivable from the bank, issued him a Form 1099-C reflecting DOI income for 1995. DOI income arises when a creditor releases a debtor from an obligation that was incurred at the outset of the debtor-creditor relationship. For Gilbert Hahn, the DOI amount was computed based on the original principal amount of the debt as well as other nonprincipal items, such as unpaid interest, penalties, and attorney’s fees (the “Related Items”). The Related Items were the focus of the Hahn decision.

Gilbert Hahn argued that the Related Items should not enter into the computation of DOI. Why? Because he never borrowed or received the Related Items. Therefore, he did not have an accession to income due to a “freeing of assets” as required for DOI income under the seminal case of United States v. Kirby Lumber31 and its progeny.32 Under the Kirby Lumber freeing-of-the-assets theory, assets previously offset by liabilities are “freed” by the transaction and DOI income results. Gilbert Hahn argued that he was never enriched because he never borrowed the amount of money constituting the Related Items.

The Tax Court refused Gilbert Hahn’s argument, at least under the facts of the case, noting that other cases have upheld DOI income resulting from the discharge of obligations—such as interest, taxes, attorney’s fees, trustee’s fees, and cash advance fees.33 The court noted that the right to use money represents a valuable property right. Therefore, the forgiveness of the Related Items resulting from the use of the funds constituting the principal borrowed beyond the time specified by the note resulted in DOI income, consistent with the Kirby Lumber freeing-of-the-assets standard. It was a straightforward decision, but certain statements made by the Tax Court merit further examination.

In support of his view that the Related Items should not be included when computing DOI, Gilbert Hahn cited Rail Joint Co. v. Commissioner34 and Fashion Park v. Commissioner.35 Of particular interest is the following statement in Hahn:

The holdings in Rail Joint Co. and Fashion Park, Inc. are consistent with section 1.61-12(c)(3) Income Tax Regs., which provides: “If bonds are issued by a corporation and are subsequently repurchased by the corporation at a price which is exceeded by the issue price * * *, the amount of such excess is income for the taxable year.”36

The Tax Court properly quoted the version of the regulation that applied during the year of Gilbert Hahn’s transactions. However, that regulation was changed, effective in 1998. To understand the confusion that the Tax Court’s statement could cause, a review of the two decisions cited in the statement is in order.

In the 1932 Rail Joint decision, a corporation distributed bonds to its shareholders as a dividend and therefore received no proceeds in return. Several years later, Rail Joint reacquired several of the bonds from its shareholders for less than face value. The Second Circuit Court of Appeals recognized that Rail Joint did not hold any additional assets after the acquisition that it had not held prior to the acquisition. Therefore, the Second Circuit ruled that Rail Joint did not recognize DOI income within the Kirby Lumber freeing-of-the-assets theory.

Fashion Park, decided in 1954, involved a more complex set of facts that may be simplified in this way. The corporation issued preferred stock with a par and stated value of $50 per share. The corporation, however, received only $5 per share on the preferred stock when it was issued. The corporation later redeemed the preferred stock for a $50 note. Subsequently, the note was satisfied for an amount greater than $5 but less than $50 (the note’s face amount). Following Kirby Lumber and Rail Joint, the Tax Court in Fashion Park held that the corporation did not have DOI income when it repurchased the note for less than its face amount, because there was no net increase in the corporation’s assets.

The Tax Court in Hahn could have harmonized the decisions in Rail Joint and Fashion Park that there was no DOI income with its decision in Hahn that there was DOI income by specifically distinguishing the source of the debt discharged. As the Tax Court noted, the Related Items arose from a borrowing of money, and it is the right to use money that represents a valuable property interest. As such, any discharge of the obligation to pay the Related Items should be included in the computation of DOI income. On the contrary, in Rail Joint, no money was borrowed. Similarly, in Fashion Park, the corporation satisfied its indebtedness for an amount in excess of the original inflow of funds from the overall transaction. Additional amounts of indebtedness that accrued on the original borrowing were not at issue.

The Tax Court instead took another approach—it distinguished Gilbert Hahn’s situation by pointing out that he did not issue bonds or other debt instruments at a discount. The court noted that, for purposes of determining the amount of DOI, it had consistently held, à la Rail Joint and Fashion Park, that the issue price of a debt, and not its face amount, should be used to determine DOI income.37 This is an interesting statement because it appears to be inconsistent with the Treasury regulation that is in effect for today’s transactions.

Before examining the change in the regulation itself, it is interesting to consider why Treasury and the IRS made the change. United States Steel Co. v. United States38 is a case that was not discussed in Hahn but merits consideration nonetheless because of its effect on the 1998 regulatory change.

The facts in United States Steel are similar to those in Fashion Park. To restate, the pertinent facts are these: In 1901, U.S. Steel issued preferred stock for $100. In 1966, as part of a merger transaction, U.S. Steel redeemed the preferred stock with a $165 note. In 1972, U.S. Steel satisfied its outstanding $165 note for $120. When United States Steel was decided, the then-current regulations generally provided that DOI income from the repurchase of debt was equal to the excess of the issue price over the repurchase price.39 The regulations, however, did not provide a definition for “issue price.” The IRS argued that the issue price of the debt was the market value of the preferred stock when the debt was issued, resulting in $45 of DOI income (the issue price of $165 less the repurchase price of $120). The Federal Circuit was not persuaded by this argument and held that the issue price of the debt was the amount the corporation received when it originally issued the preferred stock for $100, noting that it was not necessary to determine issue price for DOI purposes by reference to cases dealing with the tax treatment of bond discount.40 Consequently, the Federal Circuit found no DOI income on the debt repurchase.

The Federal Circuit United States Steel decision is consistent with the Tax Court’s Fashion Park decision. Furthermore, the regulation at issue in United States Steel is the same regulation the Hahn Tax Court found to be consistent with Rail Joint and Fashion Park. If the story ended at this point, one would not expect a corporate debtor to realize DOI income under a Rail Joint, Fashion Park, or United States Steel scenario.

It seems that the Treasury and/or the IRS was not pleased with the loss in United States Steel. In what could be viewed as a stealth regulatory reversal of United States Steel and Fashion Park, the Treasury amended the regulations to define the amount of the debt used to compute DOI income by reference to the original issue discount (OID) rules, as part of a large regulatory package addressing the OID provisions.41

The regulation cited by the Hahn court provided that the calculation of DOI income on the repurchase of corporate debt is the excess of the issue price over the repurchase price. The calculation of DOI income on the repurchase of debt is currently addressed in section 1.61-12(c)(2)(ii) of the Treasury regulations, which provides that “[a]n issuer realizes income from the discharge of indebtedness upon the repurchase of a debt instrument for an amount less than its adjusted issue price (within the meaning of Treas. Reg. section 1.1275-1(b)).” The “issue price” of the old regulations is now the “adjusted issue price” as defined in the OID regulations.

Consequently, if the adjusted issue price of the discharged indebtedness in United States Steel and Fashion Park had been determined based on the debt’s fair market value, face amount, or some type of yield-to-maturity method (as would generally be the case under the current OID regulations), the satisfaction of the debt for less than this amount would appear to result in DOI income. Perhaps the current regulation also has implications for the fact pattern in Rail Joint—that is, a fact pattern in which debt distributed by a corporation as a dividend that has an adjusted issue price (within the meaning of the OID rules) when issued and is later satisfied for a lesser amount.42

Depending on the facts, the version of the regulations cited by the Hahn court and the current version of the regulations could yield different results. So what is the moral of the story? Be careful when citing statements made by a court because, although such statements may be perfectly correct within the parameters of the case, they may not be correct or may trigger other issues on a going-forward basis.

(iv) Income Other than Discharge of Indebtedness

Cancellation of debt may be the medium through which other types of income arise, if the relationship of the parties is more than debtor-creditor—such as employer and employee, shareholder and corporation, or buyer and seller of property. The characterization and tax consequences of the transaction depend on the relationship of the parties and the context in which the discharge occurs. In Spartan Petroleum Co. v. United States,43 for example, a reduction of a debt was viewed simply as the means used to pay for property.

Debtors may set off obligations, as illustrated by this example: Mr. X owes Mr. Y $100 and Mr. Y also owes Mr. X $100. Rather than paying each other $100, the two debts are set off against each other. Neither has DOI income. The Bankruptcy Code generally preserves a creditor’s right to offset mutual obligations between the creditor and a bankrupt debtor. In an analogous vein, in OKC Corp. v. Commissioner,44 the Tax Court held that a cancellation of debt was merely a means of settling a claim. The IRS reached a similar conclusion in Revenue Ruling (Rev. Rul.) 84-176,45 finding that cancellation of debt in exchange for a release of a contract counterclaim does not result in DOI income.

If a corporation makes a bona fide loan to a shareholder, or a corporation acquires a shareholder’s debt from a third party, and the corporation subsequently cancels the shareholder’s obligation, the cancellation may be a distribution.46 The amount of the distribution may not be equivalent to the amount of the debt canceled, however. Assume that on January 1, 2000, a corporation loaned its sole shareholder $100 with a 10-year term to maturity. The debt bore a 5 percent rate of interest, payable annually, which reflected a market rate of interest. On January 1, 2004, the corporation canceled the $100 principal obligation. At this time, interest rates in the market had risen to 9 percent. Assume that the value of the debt (a $100 receivable in the hands of the corporation) dropped to $85 as a result of the rise in interest rates. I.R.C. section 301(b) provides that the amount of any distribution is the fair market value of the money received by the shareholder, plus the fair market value of the other property received. One approach suggested by revenue rulings is to bifurcate the transaction. That is, the debt cancellation results in a distribution to the extent of the fair market value of the debt ($85) and DOI income with respect to the remainder ($15).47 This bifurcation concept may also apply to loans between employers and employees. Another approach ignores the difference between the amount of the debt and its fair market value and treats the face amount of the debt as the amount of the distribution.48

The cancellation of an obligation between an employer and an employee may be a payment for services.49 If an employer makes a bona fide loan to an employee and in a later year cancels the debt in exchange for overtime services, the cancellation should be treated as compensation from both the employee-debtor’s and the employer-creditor’s perspectives. Treating the discharge as payment for services rather than DOI income results in significant differences with respect to (1) the employee’s ability to take advantage of the section 108 income exclusions discussed in §§ 2.6(a)–(d), (2) the timing of the income (if the advance of money is a prepayment for services rather than a bona fide loan), and (3) the corporation’s ability to deduct the amount as compensation expense as opposed to a bad debt. If the debt has depreciated in value at the time it is forgiven as compensation, it may be more appropriate to bifurcate the cancellation as compensation up to the value of the debt (which should equal the value of the services performed) and DOI income with respect to any remaining amount.

Due to the variety of financial arrangements in employment relationships, there are many ways in which something that facially resembles debt discharge is actually a payment for services. For example, employers often pay the moving expenses of an employee who generally agrees to repay those expenses if the employee quits within a certain time frame. If the employee does quit, the employer may cancel the reimbursement obligation. In a private letter ruling,50 the IRS determined that the canceled obligation must be reported as income on a W-2 (i.e., as wages) because the indebtedness arose as a result of an employment relationship.

Another example of compensation resulting from debt discharge arises when an employer transfers property to an employee in exchange for a note, which is later reduced or canceled. Generally, the amount of compensation the employee includes in gross income is the excess of the fair market value of the property over the amount (if any) paid for the property. Debt may be treated as an amount paid for the property, thereby lowering the amount the employee includes in gross income. The forgiveness or cancellation of that debt, in whole or part, will be included in the gross income of the employee as compensation rather than DOI income.51

(v) No Income

I.R.C. section 108(f) provides a special rule for the cancellation of student debt. The gross income of an individual does not include DOI income attributable to the forgiveness of certain student loans. I.R.C. section 108(f) excludes something from gross income that would otherwise be DOI income; there are several other situations where a discharge of debt does not result in income from the start.

A cancellation of debt may result in no income if the discharge is a gift.52 This is fairly easy to envision among family members or individuals with personal relationships. The issue that has created more confusion is whether a cancellation of debt may be treated as a gift in a commercial context. The Supreme Court originally held that a commercial discharge was a gift in Helvering v. American Dental Co.,53 but later in Commissioner v. Jacobson,54 the Supreme Court held that a commercial discharge was not a gift and resulted in DOI income. Uncertainty remained because the Jacobson decision did not overrule American Dental. Congress resolved this issue in the legislative history to the Bankruptcy Tax Act of 1980, which provides that gifts do not occur in a commercial context.55

A guarantor does not realize income when the primary debtor makes a payment or satisfies the debt. In Landreth v. Commissioner,56 the Tax Court held that a guarantor does not realize DOI income when the principal debtor discharges the debt. In reaching this conclusion, the Tax Court contrasted the impact of a cancellation of debt on a primary debtor with the impact on a guarantor. If the obligation of a debtor is relieved, the debtor’s net worth increases and the debtor may have DOI income under Kirby Lumber.57 However, when a guarantor is relieved of the contingent liability, either because of payment by the debtor or a release given by the creditor, there is no accretion of assets.58 The payment by the debtor did not result in an increase in the guarantor’s net worth, it merely prevented a decrease in the guarantor’s worth. The Tax Court concluded that the “guarantor no more realizes income from the transaction than he would have if a tornado, bearing down on his home and threatening a loss, changes course and leaves the house intact.”59

(vi) Contested Liability Doctrine and Unenforceable Debt

Under the contested liability doctrine, a taxpayer who disputes the original amount of a debt and later settles with the creditor on a lesser figure can use the lower amount when computing DOI income. That is, the excess of the original debt over the amount later determined to be correct may be disregarded in calculating gross income.60 Situations that invoke the contested liability doctrine often involve debt that may not be enforceable, which invokes another rule: If there is no legal obligation to pay the debt, there is no income when that “debt” is discharged.

The Third Circuit considered the contested liability doctrine and unenforceable debt in Zarin v. Commissioner.61 This case involves a $3.4 million gambling debt that arose when Mr. Zarin borrowed gambling chips from a casino. He immediately lost the chips and eventually settled the matter with the casino for $500,000. The Tax Court held that Mr. Zarin realized DOI income in an amount equal to the difference between the amount borrowed and the amount paid. The Third Circuit reversed on two grounds. The first and more compelling reason was that Mr. Zarin did not have a legal liability to the casino. Applicable law prohibited the casino from providing a marker to Mr. Zarin in the amount that it did, so he was not legally obligated to satisfy the debt. The gambling debt did not meet the definition of indebtedness in I.R.C. section 108(d)(1), so its discharge was not income under I.R.C. section 61(a)(12).62 The second reason was application of the contested liability doctrine. The casino and Mr. Zarin settled the unenforceable debt for $500,000, which Mr. Zarin paid. Because Mr. Zarin owed and paid the same amount, there was no DOI income. The authors do not find much comfort in or basis for this rationale given the facts at issue in Zarin.

The Third Circuit’s holding in Zarin has been questioned by other courts. In Preslar v. Commissioner,63 the Tenth Circuit found that the Third Circuit improperly applied the contested liability doctrine to unenforceable debt, confusing liquidated debt with unliquidated debt. According to the Tenth Circuit, the contested liability doctrine only applies to unliquidated debt, that is, the theory applies when the exact amount of consideration that initially exchanged hands is unclear.64 A total denial of liability or a challenge to the enforceability of the underlying debt does not go to the amount of the underlying debt. The Tenth Circuit found that in such a situation, the infirmity exception to the purchase price adjustment rule (which is discussed in § 2.5(b)) would apply, but the contested liability doctrine would not.

At least one court sidestepped the contested liability doctrine by resorting to the tax benefit rule. In Schlifke v. Commissioner,65 the Tax Court avoided the necessity of cutting its “way through the thicket of subissues . . . such as the presence of a liquidated, as distinguished from an unliquidated indebtedness, and the enforceability of the underlying obligation, i.e., whether it is void or voidable and the impact of the element of rescission”66 by applying the tax benefit rule. To simplify the facts of the case, Republic Home Loan (Republic) loaned $100 to the Schlifkes, who paid $20 in interest on the loan and deducted $20 as interest expense. The Schlifkes rescinded the loan three years later because it violated the Truth in Lending Act. As part of the rescission, the previously paid $20 in interest was applied against the $100 principal of the loan, reducing the Schlifkes’ debt to $80.

The Tax Court adroitly avoided DOI income issues by applying the tax benefit rule. Under the tax benefit rule, if an amount deducted from gross income in one tax year is recovered in a subsequent tax year, the recovery is included in gross income in the year of receipt, to the extent the prior deduction resulted in a tax benefit.67 The Tax Court held that under the tax benefit rule, the Schlifkes had taxable income of $20. The court cited and quoted Hillsboro National Bank v. Commissioner for the proposition that the tax benefit rule triggers income where a “subsequent recovery . . . would be fundamentally inconsistent with the provision granting the deduction.”68

The Tax Court’s ultimate holding in Schlifke may be correct, namely that the taxpayers should include income. The outcome is consistent with the Supreme Court’s later decision in Centennial Savings. The Tax Court in Schlifke, however, could have concluded that there was no discharge of indebtedness under Zarin, because the taxpayer fulfilled its legal liability under the terms of the note and applicable law. We will never know. The Tax Court’s short-shrift approach, completely discarding the characterization of the income as discharge of indebtedness, is not a recommended analysis. Although the characterization of the income may not have made a difference under the facts of the case, it could easily have significant implications if the debtor were in bankruptcy or insolvent.

The IRS addressed another situation in which the characterization of income as includible under the tax benefit rule or excludible as DOI under I.R.C. section 108 was at issue. This is discussed in greater detail in § 2.6(e) below.

(b) Is the Obligation Indebtedness?

Another threshold issue is whether the obligation is “indebtedness” for federal income tax purposes. If the instrument is not “indebtedness,” then the I.R.C. section 108 rules do not apply. For closely held corporations, the nature of an instrument as debt or equity may be questioned. In general, debt qualifies as indebtedness for federal income tax purposes in part if the amount of the obligation does not exceed the amount that a reasonable unrelated lender would lend to the debtor under commercially reasonable terms.69

(c) Who Is the Debtor?

If there are multiple debtors liable for a debt that is canceled, any DOI income must somehow be allocated among the debtors. Stated another way, who is the debtor for federal income tax purposes? In a private letter ruling,70 a partnership owned an insolvent corporation, and both were jointly and severally liable on bank debt. As part of a settlement with the bank, the partnership satisfied the debt for less than the amount due. The IRS found that the corporation (not the partnership) recognized DOI income, which was excluded to the extent of its insolvency.

Another case involving the identity of the debtor is Plantation Patterns, Inc. v. Commissioner.71 A corporation issued debentures that were personally guaranteed by its sole shareholder.72 Even though the corporation made all payments due on the debentures, the Fifth Circuit considered the circumstances that existed when the debentures were issued and held that the debentures were not indebtedness of the corporation. Thus, the corporation was not a debtor and not entitled to deduct the payments made on the debentures as an interest expense. Rather, the Fifth Circuit treated the debentures as a contribution of capital by the shareholder and treated the corporation’s payments as distributions to the shareholder.73

The authors have often seen practitioners express undue concern regarding a Plantation Patterns issue. Not every shareholder guarantee of a corporation’s debt results in this treatment. Even if a lending institution would lend money to a corporation on a stand-alone basis, those institutions commonly require a shareholder guarantee when the corporation is closely held. Under these circumstances, the corporation’s obligation should be treated as indebtedness and not recast under Plantation Patterns.

(d) When Does Discharge of Indebtedness Income Occur?

Sometimes the issue is not whether DOI income exists but when it occurs. Debt is discharged when it becomes clear that the debt will never have to be paid, based on a practical assessment of the facts and circumstances.74 The courts require only that the time of discharge be fixed by an identifiable event. Repayment of the loan need not become absolutely impossible before a debt is considered discharged. A slim possibility of repayment does not prevent a debt from being treated as discharged. Whether a debt has been discharged depends on the substance of the transaction. The courts look beyond formalisms, such as the surrender of a note or the failure to do so.75

Corduan v. Commissioner76 not only provides another example of what is income from debt cancellation but also sheds some light on when that income is realized. The taxpayer owned a piece of equipment subject to recourse debt of $18,581. The creditor repossessed the equipment, which had a fair market value of $12,575. The taxpayer and the creditor later agreed that the taxpayer would pay the creditor $1,000 and the creditor would release the taxpayer from the remaining debt. Debt is considered discharged “the moment it is clear that it will not be repaid.” Using this standard, the Tax Court held that the taxpayer had DOI income of $5,006 ($18,581 less $12,575 less $1,000) when the creditor released the taxpayer from further obligations under the debt, not when the creditor repossessed the equipment.

In Milenbach v. Commissioner,77 the Ninth Circuit considered the timing of DOI income. The taxpayer owned the Los Angeles Raiders and the case arose from the nomadic nature of the team. In 1987, the Raiders tried to move from Los Angeles to Irwindale, California. In connection with the move, the Raiders executed a memorandum of agreement (MOA) with the city of Irwindale for a $115 million loan to finance a football stadium. Irwindale advanced the Raiders $10 million of the $115 million. The MOA provided that, if Irwindale failed to perform its obligations, the Raiders’ obligations would be extinguished, including the obligation to repay the advance. The Raiders would be allowed to keep the advanced funds “as consideration for the execution” of the MOA. The MOA stated that Irwindale proposed to finance the stadium by issuing general obligation bonds. In 1988, the California legislature passed a statute that precluded the use of general obligation bonds to build a stadium. Despite this legislation, the Raiders continued to negotiate with the city through 1990 to construct a stadium in Irwindale. All alternative financing schemes were rejected, however. The Raiders never repaid the $10 million advance.

The classification of the $10 million as DOI income was not in dispute in Milenbach.78 The timing of the DOI income was the issue. The Tax Court held that the Irwindale debt was discharged in 1988, primarily because the 1988 legislation made financing the stadium with general obligation bonds impossible. The Ninth Circuit disagreed, finding that although the parties assumed that Irwindale would fund the loan with these general obligation bonds, that funding was not required by the MOA. Forfeiture would occur only if Irwindale was unable to provide the funds, from whatever source. The passage of the 1988 legislation was simply an obstacle that the Raiders and Irwindale attempted to overcome. The Ninth Circuit remanded the matter to the Tax Court to determine when the Irwindale debt was discharged, directing the Tax Court to perform a “practical assessment of the facts and circumstances relating to the likelihood of payment” to determine when, as a practical matter, it became clear that Irwindale would not be able to fund the entire loan and that the stadium would not be built.

A recent chief counsel advice memorandum addressed the timing of DOI.79 The debt at issue became the subject of complex litigation. Ultimately, the debtor and creditor negotiated a settlement agreement regarding amounts owed. The settlement agreement specified a creditor effective date when the taxpayer was discharged from all indebtedness and the notes were canceled. In furtherance of the settlement agreement, the parties filed a motion to dismiss with prejudice the various lawsuits, and the court granted the motion. The creditor effective date was many months after the court order date.

The author of the chief counsel advice memorandum concluded that the discharge of the taxpayer’s indebtedness did not occur as of the court order date and instead occurred, under the terms of the settlement agreement, as of the creditor effective date. As of the court order date, the creditor still had rights with respect to the notes that could be judicially enforced: “. . . in the event a payment was not received by Creditor pursuant to the Settlement Agreement, Creditor could seek subsequent judicial assistance in enforcing the Settlement Agreement.”80

§ 2.4 SECTION 108(e) ADDITIONS TO DISCHARGE OF INDEBTEDNESS INCOME

(a) Debt Acquired by Related Party: Section 108(e)(4)

As discussed in § 2.3(a)(iii), a debtor may have DOI income when it repurchases its own debt for less than the adjusted issue price.81 A debtor cannot avoid the DOI income by inducing a related party to purchase the debt at a discount because I.R.C. section 108(e)(4) recharacterizes the purchase by the related party as a purchase by the debtor.

(i) Related Party

I.R.C. section 108(e)(4) identifies a “related party” by cross-reference to the relationships in I.R.C. sections 267(b) and 707(b)(1), which include family members, shareholders and controlled corporations, fiduciaries and beneficiaries of a trust, and many others. For example, a person is considered related to the debtor if that person is any of the following:

- A member of a controlled group (for purposes of I.R.C. section 414(b)) of which the debtor is also a member82

- Under common control with the debtor as defined in I.R.C. section 414(b) or (c)

- A partner in a partnership that the debtor controls (owns more than 50 percent of the capital interest or profit interest)

- A partner in a partnership that is under common control as defined in I.R.C. section 707(b)(1)

The Bankruptcy Tax Act does provide for some exceptions to the related party rules. As one example, brothers and sisters of the debtor are not related parties. Other family members—the debtor’s spouse, children, grandchildren, parents, and any spouse of the debtor’s children or grandchildren are related parties.83

(ii) Acquisition by a Related Party

Under I.R.C. section 108(e)(4), the acquisition of the debt of a related party from a person who is not a related party can result in DOI income to the debtor (a “direct acquisition”). Thus, if a parent corporation (P) purchases the debt of its subsidiary (S) on the open market for an amount less than the adjusted issue price, there is DOI income to S. The tax consequences may be the same if the steps are reversed; that is, S acquires the debt of P in the open market at a time when S and P are unrelated, but, at a future date, P purchases the stock of S (an “indirect acquisition”).

(A) Direct Acquisition

The current regulations, Treas. Reg. section 1.108-2, cover both direct and indirect acquisitions. A “direct acquisition” is defined as an acquisition of outstanding debt if a person related to the debtor (or a person who becomes related to the debtor on the date the debt is acquired) acquires the debt from a person who is not related to the debtor. Thus, if P owns all the stock of S, P’s acquisition of S’s debt, or vice versa, is a direct acquisition. Likewise, if on the same day P acquires all the stock of S from unrelated X and P acquires all the S debt from unrelated Y, there is a direct acquisition within the meaning of I.R.C. section 108(e)(4), and S has DOI income.

The IRS is studying transactions in which P acquires the S stock and the S debt from the same person in the same transaction, to see whether these transactions should be excluded from the definition of a direct acquisition.84

(B) Indirect Acquisition

Indirect acquisitions, which fall outside the literal language of I.R.C. section 108(e)(4), achieve the same result as direct acquisitions. In response to these indirect acquisitions and to prevent abuses under I.R.C. section 108(e)(4), the government issued regulations, at Treas. Reg. section 1.108-2.85 Under the current regulations, an indirect acquisition is a transaction in which a holder of the debt becomes related to the debtor, if the holder acquired the debt in anticipation of becoming related to the debtor. Assume P and S are unrelated to each other. P has outstanding debt in the hands of unrelated parties. S buys the P debt in anticipation of P’s acquisition of the stock of S. Shortly thereafter, P buys all the stock of S. The discharge of indebtedness rules and I.R.C. section 108(e)(4) apply. Similarly, if S had outstanding debt held by unrelated parties, the acquisition by P of the S debt in anticipation of P’s buying the S stock is also an indirect acquisition.

The contentious phrase in the definition of an indirect acquisition is “in anticipation of becoming related.” A holder of the debt is treated as having acquired that debt in anticipation of becoming related if the relationship is established within 6 months after the debt is acquired. This appears to be a conclusive presumption. If the relationship is not established within six months, “all facts and circumstances will be considered . . . including the intent of the parties.” Specifically, the nature of the contacts between the parties, the time period during which the holder held the debt, and the significance of the debt in proportion to the total assets of the holder (or holder group)86 are considered. Curiously, the absence of discussions between the debtor and the holder does not, by itself, establish that the holder did not acquire the indebtedness in anticipation of becoming related to the debtor.

(1) Nonrecognition Transactions and DOI Income

The Treasury Department may issue regulations aimed at preventing taxpayers from using nonrecognition transactions to avoid DOI income under I.R.C. section 108(e)(4). In the preamble to the proposed Treas. Reg. section 1.108-2 regulations, the Treasury Department stated that it intended to prevent elimination of DOI income in certain nonrecognition transactions described in I.R.C. sections 332, 351, 368, 721, and 731. The preamble also provides:

In general, if assets are transferred in a tax-free transaction and the transferee receives the assets with a carryover (or, in certain cases, a substituted) basis, any built-in income or gain is taxed when the transferee disposes of the asset. If, however, the debtor acquires its own indebtedness, the indebtedness is extinguished. In that case, the indebtedness in all cases should be treated as if it is acquired by the transferee and then satisfied. Similar treatment should apply if a creditor assumes a debtor’s obligation to the creditor.

In both cases, the debt is effectively extinguished, and current recognition of income from discharge of indebtedness is appropriate. Thus, the regulations to be issued will provide for recognition of income from discharge of indebtedness in these cases.87

Although nonrecognition transaction regulations have not been issued, the regulations, when issued, would apply retroactively to March 21, 1991.88 Nonrecognition transactions involving the discharge of indebtedness should be evaluated to determine the possible retroactive application of these yet-to-be-issued regulations.

(2) Disclosure of Indirect Acquisition

In an indirect acquisition transaction, the debtor is required to disclose, by attaching a statement89 to its tax return for the year in which the debtor became related to the holder, whether either of two tests is met: (1) the 25 percent test or (2) the 6- to 24-month test.

The 25 percent test is satisfied if, on the date the debtor becomes related to the holder, the debt in the hands of the holder represents more than 25 percent of the fair market value of the assets of the holder (or holder group).90 For this computation, cash, marketable stock and securities, short-term debt, options, futures contracts, and an ownership interest of a member of the group are excluded.

The 6- to 24-month test is satisfied if the holder acquired the indebtedness less than 24 months, but at least 6 months, before the date the holder becomes related to the debtor.91

The only exception to the disclosure requirement is where the holder actually treats the transaction as a related-party acquisition under I.R.C. section 108(e)(4).92 If the debtor fails to disclose, there is a rebuttable presumption that the holder acquired the debt in anticipation of becoming related to the debtor.93

(iii) DOI Income for a Related Party Acquisition

Two things happen if either a direct or indirect acquisition occurs. First, on the acquisition date, the debtor has DOI income measured by the difference between the adjusted issue price of the debt and the related party’s basis in the debt acquired (cost). The measure is fair market value, not cost, if the holder did not acquire the debt by purchase on or less than six months before the acquisition (i.e., becoming related).94 Second, the debtor is deemed to issue a new debt to the holder in an amount equal to the amount used to compute discharge of indebtedness (cost or value).95

As an example, holder H acquires debtor D’s $1,000 face debt in the open market for $700. Five months later, H and D become related. D has DOI income of $300. D is deemed to issue a new debt to H (face $1,000 and issue price $700). Thus, D has original-issue discount deductions and H has original-issue income of $300 over the life of the old (deemed new) debt.

I.R.C. Section 108(e)(4) does not apply to all related party acquisitions of debt. For example, DOI income is not triggered if (1) the debt that is acquired in a direct or indirect acquisition has a stated maturity date within one year of the acquisition date and the debt is in fact retired on or before such date, or if (2) the acquisition of indebtedness is by certain securities dealers in the ordinary course of business.96

As a practical matter, many related party issues are covered by the consolidated tax return regulations. The application of section 108(e)(4) may be trumped by the application of the consolidated return regulations when a member of a consolidated group has its debt canceled or is deemed to have its debt discharged.97

(b) Indebtedness Contributed to Capital: Section 108(e)(6)

Even if the cancellation of a debt is structured as an otherwise tax-free contribution to capital, DOI income may be realized under I.R.C. section 108(e)(6). The tax effect of the cancellation of a loan from a corporation to its debtor-shareholder was discussed in § 2.3(a)(iv). The opposite scenario is addressed here: the shareholder’s cancellation or satisfaction of a corporation’s obligation. This situation often occurs in the consolidated group setting, where different rules, which are discussed in § 2.10, apply.98 Unlike the stock-for-debt exception under I.R.C. section 108(e)(8) discussed in § 2.4(c), the capital-contribution situation generally involves a creditor that is an existing shareholder of the debtor corporation. Nevertheless, the capital-contribution exception and the stock-for-debt exception are similar enough to overlap in many situations, as discussed in § 2.4(c)(ii).

I.R.C. section 108(e)(6) provides that if a debtor corporation acquires its debt from a shareholder as a contribution to capital, I.R.C. section 118 (which excludes contributions to capital from the corporation’s gross income) does not apply, and the corporation will be deemed to have satisfied the debt with an amount of money equal to the shareholder’s adjusted basis in the debt.

The satisfaction of a debt in exchange for stock of the debtor corporation is not considered a contribution to capital, however, if the shareholder is also a creditor and acts as a creditor to maximize the satisfaction of a claim.99 This exception might apply to situations where stock and bonds are publicly held and the creditor also happens to be a shareholder.

Shareholders that forgive corporate debt would prefer a bad debt deduction to capital contribution treatment. The shareholder was allowed a bad debt deduction rather than capital contribution treatment in Mayo v. Commissioner.100 The shareholder in Mayo forgave debt of an insolvent corporation, but the corporation was still “hopelessly insolvent, even after the cancellation.” Thus, the Tax Court held that the cancellation of debt of the insolvent corporation did not enhance the corporation’s value and, therefore, did not constitute a contribution to capital.101

Lidgerwood Mfg. Co. v. Commissioner,102 unlike Mayo, found that the shareholder made a capital contribution in the form of debt forgiveness. The Second Circuit assumed that the debtor corporation was insolvent both before and after the cancellation; however, there was no finding that the corporate debtor was “hopelessly insolvent.” The Second Circuit noted that:

[W]iping out the debts was a valuable contribution to the financial structure of the subsidiaries. It enabled them to obtain bank loans, to continue in business and subsequently to prosper. This was the avowed purpose of the cancellations. Where a parent corporation voluntarily cancels a debt owed by its subsidiary in order to improve the latter’s financial position so that it may continue in business, we entertain no doubt that the cancellation should be held a capital contribution and preclude the parent from claiming it as a bad debt deduction.103

In addition to Lidgerwood, the bulk of case law favors characterizing a shareholder’s cancellation of debt of an insolvent corporation as a contribution to capital, rather than allowing the shareholder a bad debt deduction.104

A 1998 field service advice105 cites to Mayo and Lidgerwood, while considering the tax treatment when a parent corporation (P) forgives debt of a wholly owned, and insolvent, subsidiary (S). To illustrate the determination in the field service advice, assume S is insolvent to the extent of $10 and P forgives a note with a face amount of $20, in which S has a basis of $20.

Turning first to whether P (the shareholder) made a capital contribution, the IRS applied this standard: “A shareholder generally makes a capital contribution to a debtor corporation to the extent that the shareholder’s cancellation of the corporation’s debt enhances the value of the shareholder’s stock.” The value of the stock of S, the debtor corporation, increased by the amount by which it became solvent as a result of the debt cancellation. Applying this standard to the previous numbers, the value of S stock increased from zero to $10. Under I.R.C. section 108(e)(6), S is deemed to have satisfied $10 of the outstanding debt with an amount equal to P’s $10 basis in that portion of the debt. Under the assumed facts, S would not have DOI income on the portion that qualified as a capital contribution, but if P had a lower basis in the debt, then S could have DOI income.

Recall that only $10 of the $20 of debt cancellation is treated as a capital contribution. The IRS found that S realized DOI income equal to the canceled debt that is not a capital contribution.106 Special rules that apply when an insolvent taxpayer has DOI income are discussed in § 2.6(b). Under those rules, S has all the DOI income excluded from income under the I.R.C. section 108(a)(1)(B) insolvency exclusion (i.e., to the extent of its insolvency of $10) and applied to reduce tax attributes pursuant to I.R.C. section 108(b)(1).

(i) Allocation between Principal and Interest

Allocation between principal and interest is another matter to be considered with regard to the deemed satisfaction of an outstanding debt under section 108(e)(6). If a corporation is deemed to satisfy outstanding debt (attributable to principal or loaned funds and to accrued but unpaid interest), the payment must be allocated between principal and interest. Prior law allowed the parties to decide how to allocate the payment.107 Under current law, the payment is generally first allocated to the interest component.108

(ii) Withholding Requirement

The IRS took the fiction of the deemed allocation one step further in a series of field service advices by requiring withholding for a foreign creditor that had a deemed payment of interest under I.R.C. section 108(e)(6).109 This conclusion is questionable in light of the introductory language of I.R.C. section 108(e)(6), which provides that it is “for purposes of determining income of the debtor from discharge of indebtedness.” The IRS’s position in the field service advice applies the deemed payment treatment to other purposes of the I.R.C. Extending this logic one more step, the deemed interest payment could result in an interest deduction and interest income for cash-method debtors and creditors.110

(iii) Accounting Method Differences

The effect of I.R.C. section 108(e)(6) may rectify complications caused by different accounting methods of the corporation and the shareholder, as illustrated by the next example. Assume that a cash-method shareholder lends $1,000 to an accrual-method corporation and that interest in the amount of $200 accrues on the loan, but is not paid by the corporation.111 This results in a $200 interest expense deduction to the accrual-method corporation (assuming the deduction is not deferred under section 267) but no interest income to the cash-method shareholder. If the shareholder cancels the debt as a contribution to capital, the corporation is no longer obligated to pay $1,200. Under section 108(e)(6), the corporation is deemed to satisfy the $1,200 obligation with an amount equal to the shareholder’s basis in the debt of $1,000. This means that the corporation would have DOI income of $200.112 If one follows the interest payment ordering rules, the deemed $1,000 payment would be split as follows: $200 of the deemed payment would be allocated first to the $200 accrued interest and the remaining $800 of the deemed payment would be allocated to the $1,000 of principal.113 If the accrued but unpaid interest has not yet been deducted and would be deductible on payment (for instance, in a situation in which I.R.C. section 267 might apply), some interesting and potentially inconsistent consequences could ensue.

If one follows the interest payment ordering rules, the first $200 of deemed payment could be applied to the accrued but unpaid interest, potentially resulting in $200 of interest deduction with the remaining $800 of deemed payment allocated to the $1000 of principal, resulting in $200 of DOI. Such an outcome does not appear to be the best resolution of this issue for several reasons. First, the statutory language of 108(e)(6) that creates a deemed satisfaction for purposes of determining DOI does not indicate that it applies for other purposes such as creating a deemed payment for purposes of generating an interest deduction. Second, certain preexisting case law that could be interpreted as resulting in a deemed payment beyond the scope of computing DOI is better viewed as eroded and inconsistent with section 108(e)(6) as enacted in the Bankruptcy Tax Act of 1980.114 The legislative history to the Bankruptcy Tax Act of 1980 indicates that if the I.R.C. section 108(e)(6) capital contribution rule would not be applied to prevent DOI, I.R.C. section 108(e)(2) nevertheless remains available. Thus, it is possible that under I.R.C. section 108(e)(2), accrued interest (the payment of which would result in a deduction) would not be included as DOI. The result would be that the entire payment could be allocated to the $1,000 of principal under I.R.C. section 108(e)(6), resulting in no DOI with respect to the principal under I.R.C. section 108(e)(6). The question is, which rule should trump—I.R.C. section 108(e)(2), which was enacted to address items that are deductible upon payment (even if the section 108(e)(6) capital contribution rule does not provide shelter), or the more recently enacted and generally applicable interest payment ordering rules. In this specific situation the better rule would appear to be section 108(e)(2).115

(c) Stock for Debt: Section 108(e)(8)

A debtor corporation may have DOI income if its debt is transferred to the corporation from a shareholder. Similarly, if the debt is transferred to the corporation in exchange for the corporation’s stock (making the creditor a shareholder), the debtor corporation has DOI income under I.R.C. section 108(e)(8) to the extent, if any, that the amount of the debt discharged exceeds the fair market value of the stock issued.

(i) Background

For many years, a corporation that satisfied debt with stock could take advantage of a favorable nonrecognition rule. That rule, however, eventually evolved into a recognition rule. The courts initially held that the exchange of stock for debt does not require the recognition of income. This nonrecognition rule was known as the stock-for-debt exception. The stock-for-debt exception, as originally codified, applied to solvent corporations as well as insolvent corporations and those in bankruptcy proceedings.116 The Tax Reform Act of 1984 changed this by providing for a general recognition rule for stock-for-debt exchanges and an exception to that general recognition rule for insolvent debtors and debtors in title 11 cases.117 The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993 abolished that regime by eliminating the exception for insolvent and title 11 debtors, leaving only the general recognition rule in place. Income recognized under this provision will continue to be excludable under section 108(a) for insolvent and title 11 debtors, but only at the price of attribute reduction.118

(ii) Overlap with Capital-Contribution Rule

Depending on the facts, the difference between an I.R.C. section 108(e)(6) capital contribution and an I.R.C. section 108(e)(8) stock-for-debt exchange may merely be a matter of form or may have economic significance. A corporation may also have DOI income if the holders of convertible debt convert the debt into common stock pursuant to a conversion right in the instrument.119

In this situation, which rule should govern? There are three possibilities: (1) Form governs, (2) the stock-for-debt rule trumps, or (3) the capital-contribution rule trumps. The answer may have significant tax implications.

Suppose a corporation has two 50 percent shareholders (A and B) and the corporation also has an outstanding debt to A. The satisfaction of the debt by means of a stock-for-debt exchange would change the relative ownership percentages in the corporation, an economically significant event. If shareholder A receives additional stock in satisfaction of the debt, A’s percentage of the ownership increases and B’s decreases. However, if A merely discharges the corporation’s debt by means of a capital contribution, the relative stock ownership percentages would be unchanged. The application of the stock-for-debt rule or the capital-contribution rule is straightforward in this example, depending on whether or not A receives additional stock. Substance and form are uniform.

The distinction between the stock-for-debt and capital-contribution rules blurs if a pro rata discharge of the debt among all shareholders of a debtor corporation is considered. If the discharge is pro rata, the actual issuance of additional stock in satisfaction of the debt is a mere formality without economic significance. This concept is easily illustrated in the sole-shareholder context. Assume that A owns 100 percent of the stock in corporation X, which has a bona fide debt to A. If A discharges X’s obligation, the receipt of additional shares would be economically meaningless. Whether or not additional stock is issued, the debt is discharged and A owns 100 percent of the outstanding stock of X, both before and after the discharge.

Assume Corporation Y issued a $1,000 obligation bearing a market rate of interest. The value of the obligation declines due to market fluctuations in interest, and Drew, a person unrelated to Y, purchases the obligation on the market for $950. Two years later, in an unrelated transaction, Mary acquires 100 percent of the stock of Y.120 The fair market value of the debt instrument further declines to $920. If Y satisfies the $1,000 obligation with $920 worth of its own stock, Y would realize $80 of DOI income pursuant to the stock-for-debt rule. However, pursuant to the capital-contribution rule, if Drew forgives the debt as a capital contribution, Y would realize $50 of DOI income, determined by subtracting Drew’s basis in the debt ($950) from the adjusted issue price of the debt ($1,000).

The IRS considered the overlap in two private letter rulings. In a 1989 ruling,121 form governed and the stock-for-debt rule applied. In that ruling, P, a corporation, owns all the stock and a debt instrument of subsidiary S. P surrenders the debt to S in exchange for newly issued S stock equal in value to the fair market value of the debt. Even though P is the sole shareholder of S both before and after, the IRS allowed the form to control and applied the stock-for-debt rules and not the capital-contribution rules. As a result, income to S is measured by the excess of the principal amount of the debt over the value of the stock issued, and not by the principal amount of the debt over P’s basis in the debt. Assuming the adjusted issue price of the debt and the value of the S stock are equal, S would not have DOI income.

In a 1998 private letter ruling,122 the IRS once again found that form controls and the stock-for-debt rule, and not the capital-contribution rule, applies when creditors cancel debt of a debtor corporation in exchange for debtor corporation stock. The IRS concluded that I.R.C. section 108(e)(6) did not apply because the phrase “contribution to capital” does not encompass an exchange. As a matter of form, because the debtor corporation issued stock in return for three creditors’ cancellation of indebtedness, there was not a capital contribution. The IRS further concluded that the issuance of the stock could not be disregarded because the legal relationship of the creditors to the corporation changed—before the transaction, one creditor directly owned all the stock of the debtor corporation, but as a result of the transaction, the two other creditors also became shareholders of the corporation. Thus, because the debt cancellations were not capital contributions, I.R.C. section 108(e)(6) could not apply, and therefore, the stock-for-debt rule of I.R.C. section 108(e)(8) applied.

In 2005, the IRS went the extra mile in an overlap situation and treated one discharge of corporate debt as an I.R.C. section 108(e)(6) capital contribution and treated a discharge of another debt of the same corporation as an I.R.C. section 108(e)(8) stock-for-debt exchange.123

In certain circumstances, a taxpayer may discover after the completion of a debt cancellation that one form of cancellation was more advantageous than another. In such situations, a rescission may be necessary (if it is available). In Private Letter Ruling 201016048,124 the IRS allowed a corporate taxpayer to rescind the cancellation of its debt owed to its parent in exchange for its stock. The debt cancellation would have qualified under section 108(e)(8). After the rescission, the IRS allowed the taxpayers to substitute a contribution of the debt to the capital of the subsidiary that qualified under section 108(e)(6).

Do these private letter rulings mean that form always governs in an overlap? Although tax practitioners generally regard this as the better view,125 a careful practitioner should consider the substance of the transaction and the meaningless gesture doctrine.

(A) Meaningless Gesture Doctrine

The meaningless gesture doctrine has been applied in I.R.C. section 351 exchange transactions. I.R.C. section 351 allows a taxpayer to transfer property to a controlled corporation in a tax-free exchange.126 Both the courts and the IRS have acknowledged that when a 100 percent shareholder transfers property to the corporation in a section 351 exchange, the issuance of additional shares of stock would be a meaningless gesture127 and the transfer of the property is tax-free regardless of whether additional shares are actually issued. If the meaningless gesture doctrine is applied in a pro rata debt discharge in which additional shares were not issued, the transaction could be evaluated as if the shares were constructively issued. This approach would require the stock-for-debt rules to apply in an overlap situation. This is in contrast to the approach of the IRS in several private letter rulings that blessed capital-contribution-rule treatment where no stock was issued.128