CHAPTER 8

Corporate Credit Analysis

Corporate credit analysis involves the analysis of a multitude of quantitative and qualitative factors over the past, present, and future. The past and present are introductions to what the future may hold. Corporate bond credit analysis involves an analysis of an issuer, and is not done in isolation but in conjunction with a review of the issuer's place within the industry and an overall analysis of where the industry fits within the national economy and, with increasing frequency, the global economy.

Corporate bond credit research and equity research areas historically have been viewed as separate areas, but with the development and application of option theory, these two areas of financial research are now considered to be complementary. In addition, credit risk models that are grounded in option theory are commercially available to investors.

Our purpose in this chapter is to discuss the general principles of corporate credit analysis. We begin with a discussion of the types of credit risk an investor faces when investing in a bond. We then explain the factors to consider in credit analysis: character, capacity, collateral, and covenants.

TYPES OF CREDIT RISK

An investor who lends funds to a corporation by purchasing its debt obligation is exposed to credit risk. But what is credit risk? Credit risk encompasses three types of risk:

Default risk is the likelihood that the issuer of debt is not able to meet the promised obligations to pay interest and repay the obligation. Credit downgrade risk is the risk of an increase in default risk. We refer to this risk as downgrade risk because we often observe that the company's credit rating is downgraded as default risk increases. The yield of a debt obligation will reflect the debt's risk, but credit spread risk is the uncertainty that the difference between the yield on a debt instrument and the yield for a benchmark, such as a Treasury bond, will change.

Default Risk

If a corporate bond issuer fails to make timely payment of interest and principal due to the bondholders or if it violates any provisions set forth in the bond indenture, the issuer is said to default. In that case, the issuer is required to pay off the bond issue immediately. If this cannot be done, the bankruptcy laws take over. The petition for bankruptcy can be filed either by the company itself, in which case it is called a voluntary bankruptcy, or be filed by its creditors, in which case it is called an involuntary bankruptcy.

The laws governing bankruptcy are set forth in the U.S. Bankruptcy Code.1 Under these rules, a business may file for reorganization under Chapter 11 or liquidation under Chapter 7 of the Code.2 The liquidation of a corporation means that all the assets will be distributed to the holders of claims of the corporation and no corporate entity will survive. In reorganization, a new corporate entity results. Some holders of the claim of the bankrupt corporation will receive cash in exchange for their claims, others may receive new securities in the corporation that results from the reorganization, and others may receive a combination of both cash and new securities in the resulting corporation.

Many companies that file for Chapter 11 reorganization ultimately are liquidated. For example, Circuit City, an electronics retailer, filed for bankruptcy November 10, 2008, and then liquidated under Chapter 7 in January 2009.3 When a company is liquidated, creditors receive distributions based on the absolute priority rule to the extent assets are available. The absolute priority rule is the principle that senior creditors are paid in full before junior creditors are paid anything. For secured and unsecured creditors, the absolute priority rule guarantees their seniority to equity holders.

Default risk is the risk that the corporate borrower will fail to satisfy the terms of a debt obligation, with respect to the timely payment of interest and repayment of the amount borrowed, resulting in a loss of interest and principal. Analysis of the credit default risk of an issuer or issuer is a time-consuming process. While many large institutional investors have a staff of credit analysts to analyze the credit default risk, retail investors rely on credit ratings assigned to issues by specialist companies, which are referred to as credit rating agencies.

A credit rating is a formal opinion given by a credit rating agency (CRA) of the default risk faced by investing in a particular issue of debt securities. It represents in a simplistic way the rater's assessment of an issuer's ability to meet the payment of principal and interest in accordance with the terms of the debt contract. Credit rating symbols or characters are uncomplicated representations of more complex ideas. In effect, they are summary opinions and nothing more than opinions.

In the United States, a credit rating firm registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) is a Nationally Recognized Statistical Rating Organization (NRSRO). As of early 2012, there are 10 firms registered with the SEC as NRSROs:

The three major NRSROs are Moody's Investors Service, Standard & Poor's Ratings Services, and Fitch, followed by DBRS and A. M. Best Company.5 Although retail investors gauge the default risk of an issue by looking at the credit ratings assigned to issues by one or more of these CRAs, institutional investors use ratings as a confirmation for their own analysis.

CRAs provide credit ratings for long-term and short-term debt obligations. For the long-term debt obligations (debt with an original maturity of more than one year), a credit rating is a forward-looking assessment of the probability of default and the relative magnitude of the loss should a default occur. For short-term debt obligations (debt with an original maturity of 12 months or less), a credit rating is a forward-looking assessment of the probability of default. There are different rating systems for a given CRA for short-term and long-term debt. While CRAs analyze a company when making their determination of what credit rating to assign, the credit rating is specific to the issue not the issuer.

The rating systems of the CRAs use similar symbols and it bears repeating that they are uncomplicated representations of more complex ideas. In the rating systems of all three rating agencies, the term “high grade” means low credit risk, or conversely, high probability of future payments. The highest-grade bonds are designated by Moody's by the letters Aaa, and by the others as AAA. The next highest grade is Aa (Moody's), and by the others as AA; for the third grade all CRAs use A. The next three grades are Baa (Moody's) or BBB, Ba (Moody's) or BB, and B, respectively. There are also C grades.

S&P and Fitch use plus or minus signs to provide a narrower credit quality breakdown within each class. Moody's uses 1, 2, or 3 for the same purpose. Bonds rated triple A (AAA or Aaa) are said to be “prime”; double A (AA or Aa) are of high quality; single A issues are called “upper medium grade”; and triple B are “medium grade.” Lower-rated bonds are said to have “speculative” elements or be” distinctly speculative.” Bond issues that are assigned a rating in the top four categories are referred to as investment-grade bonds.

Bond issues that carry a rating below the top four categories are noninvestment-grade bonds or more popularly referred to as high-yield bonds or junk bonds. Thus, we can divide the bond market into two sectors: the investment-grade sector and the noninvestment-grade sector. Distressed debt is a subcategory of noninvestment-grade bonds. These bonds may be in bankruptcy proceedings, may be in default of coupon payments, or may be in some other form of distress.

Reducing Reliance on External Credit Ratings

There has been a long-standing concern by regulators throughout the world regarding the reliance of investors on credit ratings assigned by NRSROs or CRAs. One commonly held view is that investors rely exclusively on ratings by CRAs. Another view is that although investors may not rely exclusively on ratings by CRAs, they have come to over rely or excessively rely on ratings. The poor performance of CRAs in the rating of subprime mortgage-backed securities has highlighted this concern. This view is expressed in a report by the Financial Stability Forum: “Investors should address their over-reliance on ratings.”6 In testimony before the U.S. Senate, John Walsh, acting Comptroller of the Currency, referred to the “undue or exclusive reliance on credit ratings.”

Although the major attack in recent years has been on credit ratings as they pertain to structured products, there is concern that there should be an independent analysis by financial institutions and asset managers of corporate credit risk.7 The Financial Stability Forum has proposed a set of principles to reduce reliance on CRA ratings in standards, laws, regulations, and market practices.8 For example, the first two principles are:

Principle I. Reducing reliance on CRA ratings in standards, laws and regulations.

Standard setters and authorities should assess references to credit rating agency (CRA) ratings in standards, laws and regulations and, wherever possible, remove them or replace them by suitable alternative standards of creditworthiness.9

Principle II. Reducing market reliance on CRA ratings.

Banks, market participants and institutional investors should be expected to make their own credit assessments, and not rely solely or mechanistically on CRA ratings.10

In 1988, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision—a committee of central banks and central bank supervisors of the major industrialized countries—introduced risk-based capital requirements for banks based on the bank's credit risk exposures. These bank regulatory requirements are known as the Basel I Accord. The revised Basel Accord that went into effect in January 2007 relies on an internal rating system developed by banks to assess credit exposure in its portfolio and in derivative transaction with counterparties. The internal rating system used by a bank is subject to strict minimum standards and monitoring by regulators.

The key here is that although one might wonder why it is necessary to learn how to perform credit analysis, because credit evaluations are provided by CRAs, regulators and the financial community at large are moving towards less reliance on such external ratings and more on independent credit analysis.

Credit Spread Risk

The price performance of a corporate debt obligation and its return over some investment horizon depends on how the credit spread changes. If the credit spread increases, the market price of the debt obligation declines. The risk that an issuer's debt obligation will decline due to an increase in the credit spread is called credit spread risk.

Credit spread risk exists for an individual issue, debt obligations in a particular industry or economic sector, and for all debt issues in the economy. For example, in general during economic recessions, investors are concerned that issuers will face a decline in cash flows that will be used to service debt obligations. As a result, the credit spread increases for all corporate issuers and the prices of all corporate debt obligations in the market decline.

While there are portfolio managers who seek to allocate funds among different sectors of the bond market to capitalize on anticipated changes in credit spreads, an analyst investigating the credit quality of an individual issue is concerned with the prospects of the credit spread increasing for that particular issue. But how does the analyst assess whether he or she believes the market will change the credit spread attributed to the issue? To understand this form of credit risk, we need to review some basic yield relationships for debt obligations.

First, the price of a bond changes in the opposite direction to the change in the yield required by the market. Thus, if yields in the bond market increase, the price of a bond declines, and vice versa. Second, the yield on a corporate debt instrument is made up of two components:

The risk premium is a spread. In the United States, we often use the yield on U.S. Treasury issues as the benchmark yield because these issues are viewed as having very minimal default risk, are highly liquid, and are not callable. The part of the risk premium or spread attributable to default risk is the credit spread. In a well-functioning bond market, we observe that at a given point in time the higher the credit rating, the smaller the credit spread.11

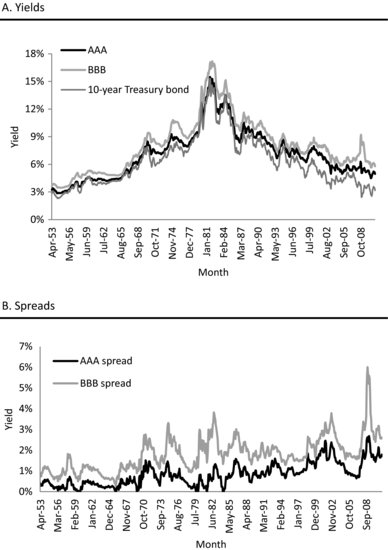

EXHIBIT 8.1 Yields and Credit Spreads for Aaa and Baa Rated Bonds, April 1953—May 2011

Source of data: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

We provide the yields on AAA rated corporate bonds, BBB rated corporate bonds, and 10-year Treasury bonds in Exhibit 8.1 for a period that spans 1953 through mid-2011. You can see in Exhibit 8.1(A) that the yields, with similar maturity, bear a relationship at a point in time.

In Exhibit 8.1(B) you can see that the credit spread varies over time. Considering the economic contraction:12

| Economic Contraction | |

| Begin | End |

| July 1953 | April 1958 |

| August 1957 | April 1958 |

| April 1960 | February 1961 |

| December 1969 | November 1970 |

| November 1973 | March 1975 |

| January 1980 | July 1980 |

| July 1981 | November 1982 |

| July 1990 | March 1991 |

| March 2001 | November 2001 |

| December 2007 | June 2009 |

Comparing the contraction periods with Exhibit 8.1(B), you can see the increase in the spreads during economic contractions.

The price performance of a corporate bond and its return over some investment horizon depends on how the credit spread changes over time. If the credit spread increases, the market price of the bond declines. The risk that an issuer's bond will decline due to an increase in the credit spread is the credit spread risk. Changes in credit spreads affect the value of debt securities and a portfolio with debt securities, and can lead to losses for bond traders or underperformance relative to a benchmark for portfolio managers. Credit spread risk exists for an individual bond issue, bonds in a particular industry or economic sector, and for all bond issues in the economy.

The value of a bond today is the discounted value of the expected interest payments and principal repayment, where this discount rate is the bond's yield. If interest rates rise, the value of the bond falls; if interest rates fall, the value of the bond increases. Therefore, investors in bonds are interested in how sensitive a bond's value is to changes in interest rates. Duration is a measure of the approximate percentage change in the value of a bond or a bond portfolio when interest rates change. A useful way of thinking of duration is that it is the approximate percentage change in the value of a bond for a 100 basis point change in “interest rates.”13 So, if the duration of a bond is 5, this means that for a 100 basis point increase in interest rates, the bond's price will decline by approximately 5%.

Therefore, a bond or a portfolio of bonds is sensitive to general changes in interest rates, as well as changes in credit spreads. For example, in a recession the benchmark Treasury bond rate may not change much, but the spread relative to the Treasury bond yield is likely to increase. This is credit spread risk.

To gauge the exposure of a portfolio or an individual bond to credit spread risk requires the use of measures developed in the bond market. As we mentioned earlier, the yield on a corporate bond is the sum of the Treasury yield and the credit spread. A measure of how a corporate bond's price is likely to change if the credit spread sought by the market changes is spread duration. For example, a spread duration of 1.7 for a corporate bond means that for a 100 basis point increase in the credit spread (holding the Treasury yield constant), the bond's price will change by approximately 1.7%.

Credit Downgrade Risk

Once a credit rating is assigned to a corporate bond, a CRA monitors the credit quality of the issuer and can reassign a different credit rating. An improvement in the credit quality of an issue or issuer through a better credit rating is an upgrade; the deterioration in the credit quality of an issue or issuer through the assignment of an inferior credit rating is a downgrade.

An unanticipated downgrading of an issue or issuer increases the credit spread sought by the market, resulting in a decline in the price of the issue or the issuer's debt obligation. This risk is credit downgrade risk, which is often also referred to as migration risk because it is the risk that the debt's credit risk will migrate to another rating class. It is obviously closely related to credit spread risk because a downgrade is one of the reasons why the credit spread will increase.

Consequently, a credit rating is not a measure of the other aspects of credit risk (that is, credit ratings do not measure credit spread risk and credit downgrade risk). Yet, investors must be aware of how CRAs gauge default risk for purposes of assigning ratings in order to understand credit downgrade risk. When assessing the credit quality of a corporate issuer, an analyst often evaluates quantitative measures such as financial ratios in terms of what the CRAs require to achieve a certain rating. When an analyst expresses a view that the credit quality has deteriorated, typically the analyst means that the analysis suggests that the issue may be downgraded because the quantitative measures identified in the analysis are inferior to the benchmarks for the issue to maintain its current credit rating.

To help gauge credit downgrade risk for corporate bonds in general, the CRAs periodically publish data about how issues that they rated change over time. These data are published in the form of a table, which is referred to as a rating migration table, rating transition table, or transition matrix. Each cell in the table shows the percentage of bonds rated by the rating agency at the beginning of the study period that had their rating change to another rating by end of period. For example, it will show the percentage of bonds rated with, say, a AA rating that had a rating of say single A at the end of the period. These tables are published for different lengths of time over which rating changes are analyzed. For example, a one-year rating migration table shows the change in rating over a 12-month period.

As an example, we provide in Exhibit 8.2 a hypothetical one-year transition table that is similar to that generated by most CRAs. The rows indicate the rating at the beginning of a year. The columns show the rating at the end of the year. Look at the second row. This row shows the transition for Aa rated bonds at the beginning of a year. The number 91.40 in the second row means that on average 91.40% of Aa rated bonds at the beginning of the year remained Aa rated at year end. The value 1.50 means that on average 1.50% of Aa rated bonds at the beginning of the year were upgraded to Aaa. The value 0.50 means that, on average, 0.50% of Aa rated bonds at the beginning of the year were downgraded to a Baa rating. From Exhibit 8.2, it can be seen that the probability of a downgrade is much higher than an upgrade for investment-grade bonds. That attribute is actually observed in rating transition tables reported by CRAs.

EXHIBIT 8.2 Hypothetical One-Year Rating Transition Table

Attempts have been made to model credit migration using the transition matrix. For example, in JPMorgan's modeling of migration, credit spreads and default probabilities are included in addition to the transition matrix to explain migration.14

Bonds migrate to different rating classes over time and the credit quality of an issue changes. Christopher Gootkind reports that from 1973 to 2000, the percentage of bonds that were high-quality rated went from 58% to 25%, and the percentage of bonds rated Baa rose from 10% to 32%.15 He also demonstrates that there is increased credit volatility, with upgrades and downgrades following a cyclical pattern.16

FACTORS TO CONSIDER IN CORPORATE CREDIT ANALYSIS

In conducting credit analysis, the analyst considers the four Cs of credit:

- Character

- Capacity

- Collateral

- Covenants

The first of the Cs stands for character of management, the foundation of sound credit. This includes the ethical reputation as well as the business qualifications and operating record of the board of directors, management, and executives responsible for the use of the borrowed funds and repayment of those funds. The next C is capacity or the ability of an issuer to repay its obligations.

The third C, collateral, is looked at not only in the traditional sense of assets pledged to secure the debt, but also to the quality and value of those nonpledged assets controlled by the issuer. In both senses the collateral is capable of supplying additional aid, comfort, and support to the debt and the creditor. Assets form the basis for the generation of cash flow that services the debt in good times as well as bad.

The final C is for covenants, the terms and conditions of the lending agreement. Covenants are restrictions on how management operates the company and conducts its financial affairs. Covenants may restrict management's discretion. A default or violation of any covenant may provide a meaningful early warning alarm, enabling investors to take positive and corrective action before the situation deteriorates further. Covenants have value as they play an important part in minimizing risk to creditors. They help prevent the unconscionable transfer of wealth from debt holders to equity holders.

Analysis of an Issuer's Character

In 1912, the Pujo Committee, a subcommittee of the House Banking and Currency Committee, investigated the “Money Trust monopoly.” The following is an exchange between the committee's counsel, Samuel Untermeyer, and the well-known financier John Pierpont Morgan:

Untermeyer: Is not commercial credit based primarily upon money or property?

Morgan: No, sir, the first thing is character.

Untermeyer: Before money or property?

Morgan: Before money or anything else. Money cannot buy it … because a man I do not trust could not get money from me on all the bonds in Christendom.

The issue of character is important, as evidenced by the financial crisis of the past few years. Investors who ignore character do so at their own peril. The analysis of characters involves reviewing the history of the business, as well as an analysis of the experience and quality of management. In discussing the factors it considers in assigning a credit rating, Moody's Investors Service notes the following regarding the quality of management:

Although difficult to quantify, management quality is one of the most important factors supporting an issuer's credit strength. When the unexpected occurs, it is a management's ability to react appropriately that will sustain the company's performance.17

In assessing management quality, the rating analysts at Moody's, for example, try to understand the business strategies and policies formulated by management.

The factors that rating agencies consider in assessing management quality include:

- Company goals and strategy

- Risk tolerance

- Internal control systems

- Corporate governance

- Track record

- Financial planning18

Analysis of the Capacity to Pay

In assessing the ability of an issuer to pay, an analyst evaluates the company's financial condition and operating performance, as we discussed in earlier chapters. The goal in evaluating a company's capacity to pay is to assess whether the company's future cash flows are sufficient to satisfy the obligations to pay interest and repay the debt as promised. However, we should note that there are generally many factors contributing to a company's lack of capacity to pay and there is no well-specified theory of why companies fail. Therefore, assessing a company's capacity to pay is not straightforward.

Factors to Consider

In a study of credit quality of U.S. corporate debt, Blume, Lim, and Mackinlay examine the financial characteristics of bonds that are rated in the four investment-grade categories (AAA, AA, A, and BBB).19 The financial characteristics they examine are the interest coverage ratio, the operating margin, the long-term debt-to-assets ratio, and total debt-to-assets ratio. They found that these financial characteristics distinguish the bonds in the different rating categories. Higher quality bonds are distinguished by their lower financial risk and higher profitability. Blume, Lim, and Mackinlay also observe that higher-quality bonds are issued by larger firms (as measured by market capitalization), which suggests some consideration for factors beyond financial ratios (e.g., established product lines).

In addition to management quality, the factors examined by analysts at Moody's include:

- Industry trends.

- Regulatory environment.

- Basic operating and competitive position.

- Financial position and sources of liquidity.

- Company structure.

- Parent company support agreements.

- Special event risk.20

Industry trends are critical to the analysis. It is only within the context of an industry is a company analysis valid. For example, if the annual growth rate of a company is 20%, on a stand-alone basis, that may appear attractive. However, if the industry is growing at 40% per year, the company is competitively weak.

In considering industry trends, analysts look at a number of factors, including:

- Economic cyclicality.

- Degree of competition.

- Degree of regulation.

- Sources of supply.

- Growth.

- Research and development expenses.

- Labor.

- Accounting.

- Sensitivity to changes in technology.21

The analyst must be sure to look at the vulnerability of the company to economic cycles, the barriers to entry, and the exposure of the company to technological changes. For firms in regulated industries, proposed changes in regulations must be analyzed to assess their impact on future cash flows. At the company level, diversification of the product line and the cost structure are examined in assessing the basic operating position of the firm.

In addition to the measures described in previous chapters for assessing a company's financial position over the past three to five years, an analyst must look at the capacity of a firm to obtain additional financing and back-up credit facilities. Back-up credit facilities are additional sources of financing that may be called upon if needed. There are various forms of back-up facilities. The strongest forms of back-up credit facilities are those that are contractually binding and do not include provisions that permit the lender to refuse to provide funds. An example of such a provision is one that allows the bank to refuse funding if the bank feels that the borrower's financial condition or operating position has deteriorated significantly.22 Noncontractual facilities such as lines of credit that make it easy for a bank to refuse funding should be of concern to the analyst. The analyst must also examine the quality of the bank providing the back-up facility.

Analysts should also assess whether the company can use securitization as a funding source for generating liquidity. Asset securitization involves using a pool of loans or receivables as collateral for the issuance of a security referred to as an asset-backed security. The decision of whether to securitize assets to borrow or use traditional borrowing sources is done on the basis of cost. However, if traditional sources dry up when a company faces a liquidity crisis, securitization may provide the needed liquidity. An analyst should investigate the extent to which management has considered securitization as a funding source.

Other sources of liquidity for a company may be third-party guarantees, the most common being a contractual agreement with its parent company. When such a financial guarantee exists, the analyst must undertake a credit analysis of the parent company.

Bankruptcy Prediction Models

Analysts and researchers use various statistical techniques to assess the potential likelihood of bankruptcy. These techniques include multiple discriminant analysis, linear probability models, and hazard models. The models that use these techniques all use financial ratios in some manner to predict whether the company is likely to fail.

For example, we can use multiple discriminant analysis (MDA) to identify those financial characteristics that distinguish companies on the basis of capacity to pay. In analyzing credit default risk, the primary advantage of using MDA is that it allows an analyst to simultaneously consider a large number of characteristics and does not restrict an analyst to a sequential evaluation of each individual attribute.

In his 1967 doctoral dissertation, Edward I. Altman established the baseline of bankruptcy prediction, using MDA to discriminate between bankrupt and nonbankrupt companies. The financial variables that have been found by Edward Altman to be important for predicting corporate bankruptcy using MDA are:

In his original work, published in 1968, Altman estimates the following model:

Z = 1.2 X1 + 1.4 X2 + 3.3 X3 + 0.6 X4 + 0.999 X5

The output of the MDA is a score (hence MDA is called a credit scoring model) that is used to classify firms with respect to whether or not there is potentially a serious credit problem that would lead to bankruptcy. If the calculated value of Z (referred to as the “Z-score”) is above 2.675, this indicates a low risk of bankruptcy; if the Z-score is below 1.81, this indicates a high risk of bankruptcy and if the Z-score fall between 1.81 and 2.675, it is unclear.24

A modification of this model to accommodate nonmanufacturers is to drop the turnover ratio and use re-estimated coefficients:25

Z* = 6.56 X1 + 3.26 X2 + 6.72 X3 + 1.05 X4

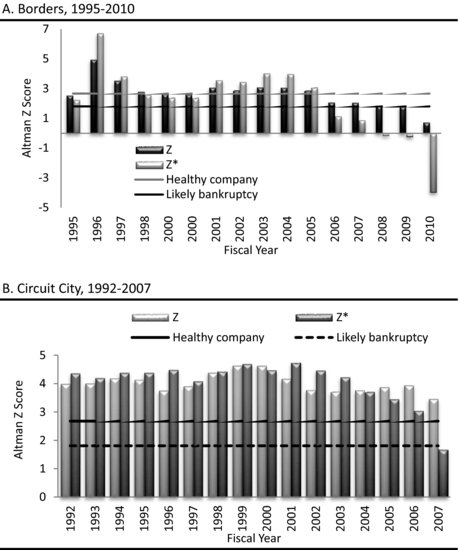

Applying the basic model and the variation for nonmanufacturers to actual companies, we see that Borders has Z and Z* scores of 0.73 and −3.97, respectively, for 2010, which is the year before its filing for bankruptcy. This indicates that the company has a high risk of bankruptcy. We can see the pattern of Z and Z*-scores in Exhibit 8.3(A).

EXHIBIT 8.3 Z-scores and Z*-scores for Selected Companies

Source of data: Financial data from 10-K filings by the respective companies, various years and stock price data from Yahoo! Finance.

Circuit City, as we show in Exhibit 8.3(B), had declining Z-scores, with Z*-scores that indicates a high risk of bankruptcy only in 2007. Circuit City filed for bankruptcy in November of 2008.

In 1977, Edward Altman, Robert G. Haldeman, and P. Narayanan updated the basic model, creating the ZETA® model.26 This is a proprietary model, so we don't have the ability to report the details here or apply the model. The primary modifications that the researchers made were to adapt the model to consider that large firms—that once were considered too large to fail—do, in fact, fail. Another modification was to make the model more applicable to nonmanufacturing sectors. A further modification was to update the model to consider changes in accounting. One of these changes has been the movement of more off-balance sheet debt to the balance sheet, which then changes the estimated role of each variable in the model.

The ZETA® model consists of seven variables:

- Operating return on assets, which is the ratio of earnings before interest and taxes to total assets.

- Variability of operating earnings, measured as the standard error of estimate of EBIT/Total assets (normalized) for 10 years.

- Debt service, which is the ratio of earnings before interest and taxes to interest charges.

- Cumulative profitability, which is measured as the ratio of retained earnings to total assets.

- Liquidity, captured by the current ratio, which is the ratio of current assets to current liabilities.

- Capitalization, which is the ratio of the five-year average market value of shareholders' equity to total capital.

- Size, measured as the company's total tangible assets, normalized to reduce the effect of outliers.

The most important variable in this model is the cumulative profitability and the next-most important variable is the variability of operating earnings.

Carol Osler and Gijoon Hong report Z-scores for a large sample of companies in the U. S. for the Altman model and variations to this model, such as that hazard model of Tyler Shumway.27 They observe that the Z-scores rose, on average, over the 1995–1999 period due to the run-up in prices in the market that was fueled by Internet companies. Market value of equity is the numerator of the X4 variable and, hence, inflated stock prices affect the Z-score.

Whereas credit scoring models have been found to be helpful to analysts and bond portfolio managers, they do have limitations as a replacement for human judgment in credit analysis. Marty Fridson, for example, provides the following sage advice about using MDA models:

[Q]uantitative models tend to classify as troubled credits not only most of the companies that eventually default, but also many that do not default. Often, firms that fall into financial peril bring in new management and are revitalized without ever failing in their debt service. If faced with a huge capital loss on the bonds of a financially distressed company, an institutional investor might wish to assess the probability of a turnaround—an inherently difficult-to-quantify prospect—instead of selling purely on the basis of a default model.28

Fridson also notes that one must recognize that “companies can default for reasons that a model based on reported financial cannot pick up.”

In addition to MDA, there are several other statistical techniques that can be used in predicting bankruptcy. Several of these fall into the class of multiple regression models: linear probability model, probit regression model, and logit regression model. In all of these models applied to predicting default, the dependent variable is “default” or “nondefault.”29

A linear probability model is the simplest type; however, a major drawback of the model is that the predicted value may be negative. Probit regression model is a nonlinear regression model where predicted values (the probabilities) fall between 0 and 1 because what is being predicted is based on the standard normal cumulative probability distribution. As with the probit regression model, the logit regression model is a nonlinear regression model and the predicted value is also based on a cumulative probability distribution. However, rather than being a standard normal cumulative probability distribution, it is a standard cumulative probability distribution of a distribution called the logistic distribution.

Another related technique that can be used is a hazard model. A hazard model is similar to the regression models, but each company's life span as a healthy company enters into the estimation. An example of this is the model by Tyler Shumway. Using Altman's five-variable Z-score model but estimating the model using a hazard function, he finds that operating return on assets and capitalization are the most discriminating of the variables.

Analysis of the Collateral30

A corporate debt obligation may be secured or unsecured. As explained earlier, in the case of the liquidation of the company, the proceeds from a bankruptcy are distributed to creditors based on the absolute priority rule. This rule states that senior creditors are paid before junior creditors, and that all creditors are paid before owners receive anything. However, in the case of reorganization, the absolute priority rule rarely holds.31 That is, unsecured creditors may receive distributions for the entire amount of their claim and common stockholders may receive something, while secured creditors may receive only a portion of their claim. The reason is that reorganization requires approval of all the parties. Consequently, secured creditors are willing to negotiate with both unsecured creditors and stockholders in order to obtain approval of the plan of reorganization.

The question is then, what does a secured position mean in the case of reorganization if the absolute priority rule is not followed in reorganization? The claim position of a secured creditor is important in terms of the negotiation process. However, because absolute priority is not followed and the final distribution in reorganization depends on the bargaining ability of the parties, some analysts place less emphasis on collateral compared to the other factors discussed earlier and covenants discussed later.

The types of collateral used for a corporate bond issue are broadly classified as mortgage debt and other secured debt. Mortgage debt is debt secured by real property such as plant and equipment. The largest issuers of mortgage debt are electric utility companies. There are instances when a company might have two or more layers of mortgage debt outstanding with different priorities.32

Debt may be secured by many different assets. Collateral trust bonds and notes are secured by pledges of financial assets such as cash, receivables, other notes, debentures or bonds, and not by real property. Generally, the market value of the collateral must be at least some minimum percentage of the bonds or notes outstanding.

Railroads and airlines have financed much of their rolling stock and aircraft with secured debt. The securities go by various names such as equipment trust certificates (ETCs) in the case of railroads, and secured equipment certificates, guaranteed loan certificates, and loan certificates in the case of airlines. If a railroad, for example, buys a piece of equipment, the title to that equipment is transferred to a trustee, who, in turn, leases the equipment to the railroad and sells the trust certificates to investors.

Analysis of Covenants

Covenants are pledges or commitments that limit and restrict a borrower's activities. Some covenants are common to all indentures, such as to:

- Pay interest, principal, and premium, if any, on a timely basis.

- Maintain an office or agency where the securities may be transferred or exchanged and where notices may be served upon the company with respect to the securities and the indenture.

- Pay all taxes and other claims when due unless contested in good faith.

- Maintain all properties used and useful in the borrower's business in good condition and working order.

- Maintain adequate insurance on its properties.

- Submit periodic certificates to the trustee stating whether the debtor is in compliance with the loan agreement.

- Maintain its corporate existence.

The covenants listed above are affirmative covenants because they call upon the debtor to make promises to do certain things.

In contrast to affirmative covenants, negative covenants are those which require the borrower not to take certain actions. There is an infinite variety of restrictions that can be placed on borrowers, depending on the type of debt issue, the economics of the industry and the nature of the business, and the lenders' desires. Some of the more common restrictive covenants include various limitations on the company's ability to incur debt because unrestricted borrowing can lead a company and its bondholders to ruin. Thus, debt restrictions may include limits on the absolute dollar amount of debt that may be outstanding or may require a ratio test; for example, debt may be limited to no more than 60% of total capitalization or that it cannot exceed a certain percentage of net tangible assets.

There may be an interest or fixed charge coverage test of which there are two types. One, a maintenance test, requires the borrower's ratio of earnings available for interest or fixed charges to be at least a certain minimum figure on each required reporting date (such as quarterly or annually) for a certain preceding period. The other type, a debt incurrence test, only comes into play when the company wishes to do additional borrowing. For example, a debt incurrence test may require an interest coverage figure, adjusted for the new debt, to be at least two times for the required period prior to the financing. Debt incurrence tests are generally considered less stringent than maintenance provisions. There could also be cash flow tests or requirements and working capital maintenance provisions.

Some indentures may prohibit subsidiaries from borrowing from all other companies except the parent. Indentures often classify subsidiaries as restricted or unrestricted. Restricted subsidiaries are those considered to be consolidated for financial test purposes; unrestricted subsidiaries (often foreign and certain special-purpose companies) are those excluded from the covenants governing the parent. Often, subsidiaries are classified as unrestricted in order to allow them to finance themselves through outside sources of funds.

Limitations on dividend payments and stock repurchases may be included in indentures. Often, cash dividend payments will be limited to a certain percentage of net income earned after a specific date plus a fixed amount. Sometimes the dividend formula might allow the inclusion of the net proceeds from the sale of common stock sold after the peg date. In other cases, the dividend restriction might be so worded as to prohibit the declaration and payment of cash dividends if tangible net worth (or other measures, such as consolidated quick assets) declines below a certain amount. There are usually no restrictions on the payment of stock dividends. In addition to dividend restrictions, there are often restrictions on a company's repurchase of its common stock if such a purchase might cause a violation or deficiency in the dividend determination formulae. Some holding company indentures might limit the right of the company to pay dividends in the common stock of its subsidiaries.

Another part of the covenant article may place restrictions on the disposition and the sale and leaseback of certain property. In some cases, the proceeds of asset sales totaling more than a certain amount must be used to repay debt. This is seldom found in indentures for unsecured debt but at times some investors may have wished they had such a protective clause. At other times, a provision of this type might allow a company to retire high coupon debt in a lower interest rate environment, thus causing bondholders a loss of value. It might be better to have such a provision where the company would have the right to reinvest the proceeds of asset sales in new plant and equipment rather than retiring debt, or to at least give the investor the option of tendering his bonds.

SUMMARY

Credit analysis of a corporation involves the analysis of a multitude of quantitative and qualitative factors over the past, present, and future based on the issuer's, and, if applicable, the guarantor's, operations and need for funds. In conducting a credit examination, an analyst must consider the four Cs of credit—character, capacity, collateral, and covenants.

Character analysis involves the analysis of the quality of management, including trying to understand the business strategies and policies formulated by management.

Assessing the capacity of an issuer to pay involves an analysis of the financial statements, including the analysis of industry trends (i.e., vulnerability of the company to economic cycles, the barriers to entry, and the exposure of the company to technological changes), the regulatory environment, basic operating and competitive position, financial position and sources of liquidity, company structure, parent company support agreements (if any), and special event risk.

Statistical models have been used that, based on financial data, seek to predict corporate bankruptcy (multiple discriminant analysis) or the probability of bankruptcy (linear probability model, probit regression model, and logit regression model).

Analysis of collateral involves an analysis of the claim position of the bondholder. In the liquidation of a corporation, proceeds are distributed to creditors based on the principle of absolute priority while in a reorganization absolute priority rarely holds because reorganization requires approval of all the parties. The claim position of a secured creditor is important in terms of strength in the negotiation process in reorganization.

Covenants deal with limitations and restrictions on the borrower's activities. Affirmative covenants call upon the debtor to make promises to do certain things (e.g., make timely payments of interest and repayment of principal). Negative covenants are those which require the borrower not to take certain actions.

REVIEW

1. U.S. Code, Title 11. The most recent amendment to the code, as of this writing, was in 2005 by the Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act of 2005 (Public Law 109-8, 119 Stat. 23, April 20, 2005).

2. Chapter 11 and Chapter 7 refer to specific sections in the United States Code, Title 11. Chapter 9 applies to bankruptcies of municipalities, Chapter 12 is similar to Chapter 11 but applies only to family farmers or fishermen, Chapter 13 relates to the debt adjustment for individuals, and Chapter 15 applies to cross-border reorganizations.

3. The name, brand logo, and web site were acquired by Systemax, Inc. in 2009 to operate as an online retailer, though the actual Circuit City company was liquidated, including closing all of its retail outlets.

4. SEC, Credit Rating Agencies—NRSROs, www.sec.gov/answers/nrsro.htm.

5. An NRSRO must file Form NRSRO (17 CFR 249b.300) to be granted its registration as a NRSRO by the Securities and Exchange Commission (Securities Exchange Act of 1934 Rule 17g-1(i)).

6. Financial Stability Forum, Report on Enhancing Market and Institutional Resilience (April 2008), 37, www.financialstabilityboard.org/about/overview.htm. The Financial Stability Board (FSB) was “established to coordinate at the international level the work of national financial authorities and international standard setting bodies and to develop and promote the implementation of effective regulatory, supervisory and other financial sector policies. It brings together national authorities responsible for financial stability in significant international financial centres, international financial institutions, sector-specific international groupings of regulators and supervisors, and committees of central bank experts.”

7. Structured products include mortgage-backed securities, asset-backed securities, collateralized debt obligations, and structured investment vehicles.

8. Financial Stability Forum, Report on Enhancing Market and Institutional Resilience, 37.

9. Financial Stability Forum, Principles for Reducing Reliance on CRA Ratings, October 27, 2010, 1.

10. Ibid., 2.

11. There are several studies on the determinants of corporate credit spreads. One study finds that changes in credit spreads are driven primarily by supply and demand, rather than factors that affect the issuer's credit risk and liquidity. See Pierre Collin-Dufresne, Robert S. Goldstein, and J. Spencer Martin, “The Determinants of Credit Spread Changes,” Journal of Finance 56, no. 6 (2001): 2177–2207.

12. National Bureau of Economic Research, U.S. Business Cycle Expansions and Contractions, www.nber.org/cycles.htm.

13. A basis point is 1/100 of 1%. Therefore, if an interest rate goes from 5% to 6%, this is a 100 basis point change.

14. Bill Demchak, “Modelling Credit Migration,” in Credit: The Complete Guide to Pricing, Hedging and Risk Management, ed. Angelo Arvantis and Jon Gregory (London: Risk Books, 2001): 276–388.

15. Christopher L. Gootkind, “Improving Credit Risk Analysis,” in Fixed-Income Management: Credit, Covenants, and Core-Plus (Charlottesville, VA: Association for Investment Management and Research, 2003): 11--18.

16. Anil Bangia, Francis X. Diebold, Andre Kronimus, Christian Schagen, and Til Schuermann, “Ratings Migration and the Business Cycle, with Applications to Credit Portfolio StressTesting,” Journal of Banking and Finance 26, nos. 2–3 (2002): 445–474.

17. Moody's, “Industrial Company Rating Methodology,” Moody's Investors Service: Global Credit Research, July 1998, www.kisrating.com/include/pdf_view.asp? menu = M2 & gubun = 1 & filename = 25_36188.pdf & title = Industrial +Rating+Company+Methodology.

18. Ibid., 7; FitchRatings, Corporate Rating Methodology, www.fitchratings.com; Standard & Poor's Rating Methodology, Corporate Ratings Criteria, 20.

19. Marshall E. Blume, Felix Lim and Craig Mackinlay, “The Declining Credit Quality of U.S. Corporate Debt: Myth or Reality,” Journal of Finance 53, no. 4 (1998): 1389–1413.

20. Moody's “Industrial Company Rating Methodology,” 3.

21. Ibid.; Standard & Poor's Ratings Methodology, 17–19.

22. Such a provision is a material adverse change clause.

23. See Chapters 8 and 9 in Corporate Financial Distress and Bankruptcy: A Complete Guide to Predicting and Avoiding Distress and Profiting from Bankruptcy, ed. Edward I. Altman (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1993); and Edward I. Altman, Robert G. Haldeman, and Paul Narayann, “Zeta Analysis: A New Model to Identify Bankruptcy Risk of Corporations,” Journal of Banking and Finance 1, no. 1(1977): 29–54.

24. This is the range that Altman refers to as the “zone of ignorance.”

25. This is a model shown in Edward I. Altman, “Predicting Financial Distress of Companies: Revisiting the Z-Score and ZETA® Models,” working paper, New York University, July 2000.

26. Edward I. Altman, Robert G. Haldeman, and P. Narayanan, “ZETA Analysis: A New Model to Identify Bankruptcy Risk of Corporations,” Journal of Banking and Finance 1, no. 1 (1977): 29–54.

27. See Carol Osler and Gijoon Hon, “Rapidly Rising Corporate Debt: Are Firms Now Vulnerable to an Economic Slowdown?” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Current Issues in Economics and Finance 6, no. 7 (2000); and Tyler Shumway, “Forecasting Bankruptcy More Accurately: A Simple Hazard Model,” Journal of Business 74, no. 1 (2001): 101–124.

28. Martin S. Fridson, Financial Statement Analysis: A Practitioner's Guide, 2nd ed. (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1995), 195.

29. The primary difference among these models is the underlying assumption regarding the distribution of the probability of bankruptcy as it lies between 0% and 100%.

30. For a more detailed discussion, see Frank J. Fabozzi, Steven V. Mann, and Adam B. Cohen, “Corporate Bonds,” Chapter 12; and Martin Fridson, Frank J. Fabozzi, and Adam B. Cohen, “Credit Analysis for Corporate Bonds,” Chapter 43 in The Handbook of Fixed Income Securities, 8th ed., ed. Frank J. Fabozzi (New York: McGraw-Hill Publishing, 2012).

31. Many researchers have found that there are violations of the absolute priority rule in over 75% of reorganizations (see Julian R. Franks and Walter N. Torous, “An Empirical Investigation of U. S. Firms in Reorganization,” Journal of Finance 44, no. 3 (1989): 747–769; and Brian L. Betker, “Management's Incentives, Equity's Bargaining Power, and Deviations from Absolute Priority in Chapter 11 Bankruptcies,” Journal of Business 68, no. 2 (1995): 161–183.

22. This situation usually occurs because the companies cannot issue additional first mortgage debt (or the equivalent) under existing indentures.