CHAPTER 3

The Quality of Financial Information

Shareholders and creditors depend on the financial statements of companies that are prepared according to generally accepted accounting standards (GAAP). These financial statements have important economic consequences that include determining management compensation, the credit quality of the company's debt obligations, and compliance with loan covenants. Yet despite the important economic consequences of these financial statements, a company's management has considerable flexibility in the choice of accounting methods and estimates. This flexibility, however, creates a situation in which the accounting choices that a company makes affect reported financial information.

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 and the regulations and changes in accounting standards that followed increase the transparency of financial statements. Financial reporting by companies is considered transparent when it is easy for investors to understand the company's performance and financial condition. We associate transparency with a high quality of financial information. In terms of valuing companies, those companies with more transparent financial information will be associated with higher values than companies with nontransparent information, if everything else is the same. This is because the opaqueness of the financial information in the latter company increases the uncertainty with respect to the current and future performance of the company and, for that reason, reduces the company's value.

Aside from the lack of comparability that it presents, the wide latitude that management has in making choices and estimates allows for earnings management. Earnings management is the judicious choice of accounting methods for financial reporting to produce results that are in the best interests of the company or its management. This is different from earnings manipulation, which has a more sinister connotation, though it is admittedly sometimes difficult to distinguish management from manipulation. Earnings management involves working within the bounds of GAAP, whereas earnings manipulation involves violating GAAP.

Do companies manage earnings? There is sufficient academic research that suggests that companies do manage earnings, whether for managers' self-interests or for some other reasons (e.g., to comply with debt covenant provisions or to minimize political costs).1 The risk of this type of management is great when management's compensation depends on reported financial data, such as earnings.2 The risk is also great when management is overly concerned with achieving analyst earnings forecasts or the company is near financial data–based constraints, such as debt covenant restrictions.

The analyst must be able to detect earnings management, earnings manipulation, or any other type of management or manipulation of financial data. Financial data may be managed in many ways and it is a challenge of financial analysis to detect such management. The purpose of this chapter is to discuss the quality of financial information that companies report. There are many ways that companies can obscure the view of their financial performance and we point out some of the devices that companies may use—either intentionally or unintentionally.

We discuss several avenues for financial information management in this chapter and discuss what to look for in financial data. In particular, we discuss:

- Accruals management.

- Revenue and expense recognition.

- Non-operating and non-recurring items.

- Goodwill impairment.

- Inventory accounting.

- Depreciation.

- Income and expenses related to segments.

After discussing the detective work that can reveal earnings management, we discuss some of the tell-tale signs to look for in an analysis of financial statements.

IT'S ALL IN THE TIMING

Accruals Management

Accruals are the accounting adjustments that relate earnings to cash flows. We typically classify accruals into two types: discretionary accruals and nondiscretionary accruals. A large part of earnings management deals with accruals and, in particular, discretionary accruals.

We expect that working capital accounts will move in accordance with revenues and that depreciation is proportionate to plant, property, and equipment. Therefore, we expect that accruals will increase as revenues increase and depreciation will increase as the company increases its investment in plant and equipment. Consider the sales of goods on credit. A sale on credit does not generate a cash flow, but rather increases accounts receivable (an accrual) and income. The accruals arising from sales on credit are part of the normal course of business and fall into the class of nondiscretionary accruals; as sales increase, the balance in the accounts receivable account should increase as well.

Aside from these nondiscretionary accruals that arise from the normal course of business there are also discretionary accruals, which should catch the attention of the financial analyst. The problem that the financial analyst faces is that accruals are not conveniently disclosed on the financial statements as discretionary or nondiscretionary. Therefore, the analyst must pay attention to particular aspects of accruals that may signal earnings management.3

An example of a discretionary accrual that bears watching is the allowance for doubtful accounts. The allowance for doubtful accounts is an estimate of the uncollectible accounts receivable and serves to reduce the value of accounts receivable on the balance sheet. The amount of receivables that are uncollectible is determined by management's judgment, considering past experience, the quality of the current customer accounts, the economy, and the company's collection policies. But because the allowance is an estimate, there is some flexibility for management to determine in any given period the change in the value of doubtful accounts.

Determining whether earnings are managed by varying the allowance is not possible, yet there are some tell-tale signs: the relationship between the allowance and the balance in accounts receivable—that is, the percentage of uncollectible accounts—should be relatively constant unless there is a change in the economy overall or a change in customer base (i.e., extending credit to a broader range of credit quality). And for most companies, the allowance rate (allowance for doubtful accounts divided by the gross accounts receivable) is relatively constant. Further, because of similarities in customers within an industry, we should also find similar (but not identical) rates of uncollectible accounts within an industry.

There are companies that appear to change the rate of uncollectible accounts as their fortunes change. The ratio of the allowance of uncollectible accounts should be rather constant over time, varying primarily when there is change in product mix, a downturn in the economy, or a change in credit policies.

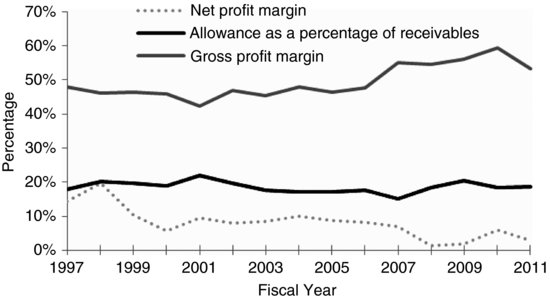

Consider the Washington Post's allowances for doubtful accounts, as we show in Exhibit 3.1. In years in which revenues began to decline and profitability changed, the allowance rate decreased. The ratio of the allowance for uncollectible accounts to accounts receivable averaged around 18.6% over the 1997–2011 period.

EXHIBIT 3.1 Profit Margins and Allowance for Doubtful Accounts as a Percentage of Receivables for Washington Post, Fiscal Years 1997 through 2011.

Source of data: Washington Post Company, 10-K filings by the various years.

Aside from looking at the relationship between specific accounts and reserves, another screen that is useful is to compare the trend in net income to that of cash flows from operations. The two trends should be moving in the same direction at the same time. We expect that the amount of cash flow from operations will be different from that of net earnings, but we expect that the changes in each series should follow a similar path. A misalignment may suggest a problem with accruals.

Let's compare two companies using this method over the period 1989–2010. First, consider General Electric. The cash flow from operations and net income follow similar paths, as we show in Exhibit 3.2(A). The correlation between these two series is 0.92, which indicates that these series are similar in terms of trends.4 This is not the same conclusion we draw from looking at the paths of cash flow from operations and net income for Eastman Kodak, as shown in Exhibit 3.2(B). In this case, the correlation of the two series is 0.32. The paths of these series are similar in the case of the earlier years for Eastman Kodak, but beginning after 2006, the paths converge. Eastman Kodak filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy January 19, 2012.5

EXHIBIT 3.2 Cash Flow from Operation and Net Income: General Electric and Eastman Kodak

Sources of data: General Electric, 10-K filings, various years; Eastman Kodak, 10-K filings, various years.

Keep in mind that there may be reasons why a company's net income and cash flow from operations differ, such as write-downs of asset values. In performing a financial analysis of a company, however, the analyst may want to identify the reasons why these two series diverge.

Revenue and Expense Recognition

One of the basic guiding principles of accounting is that revenues and expenses are matched: revenues are recognized (that is, included in income) in the period in which they are earned, and expenses are matched with revenues, matched to coordinate with the corresponding revenue. And because most companies use the accrual method of accounting, revenues and expenses recognized in a period do not necessarily correspond with the cash inflows and outflows that are the basis of the revenues and expenses. The accrual basis of accounting relies on management's discretion in determining the timing of revenue and expense recognition. Along with management's discretion, however, is the potential to manipulate income through judicious timing of revenues and expenses.

The principle of conservatism in accounting suggests that if there is some flexibility in the recognition of revenues and expenses, the most conservative approach should be used. However, the recognition of revenues and expenses requires judgment and there are many cases in which the timing decisions have raised concerns over the quality of a company's earnings. The primary techniques that have been used to inflate revenues or income are cookie-jar reserves and channel stuffing.

Cookie-jar reserves are a method of income smoothing. In a typical cookie jar scheme, a company makes inappropriate assumptions about liabilities (e.g., loan losses), often overstating them in good earnings years. And then, in a future period when earnings are not as good as expected, they reverse this transaction, hence reaching into the “cookie jar.”

Channel stuffing is the inflation of revenues of manufacturers or suppliers, and hence earnings, by forcing distributors or retail outlets to take on more units of products than they are able to sell. By forcing customers to take on more inventory than is reasonable given demand, there are likely significant returns to suppliers after the close of the fiscal period. Therefore, channel stuffing speeds up revenues and earnings at the expense of future periods' revenues and earnings.

The classic channel stuffing case is that of Sunbeam in the 1990s, but there have been other cases since then.6 Consider the case of McAfee Corporation. The SEC alleged that McAfee executives provided false and misleading financial statements through several devices:7

- Channel stuffing, which resulted in inflating revenues starting in 1998 by inducing distributors to take on more inventory than necessary by creating a wholly owned subsidiary to repurchase any oversold inventory at a profit to the distributors.

- Paying cash to distributors in place of offering discounts, giving the appearance that they were being paid in full by the distributors.

- Improper accounting of revenues, recognizing revenues in period before permissible according to GAAP.

The results of these actions were to inflate revenues and net income in the years 1998 through 2000, among other things.8

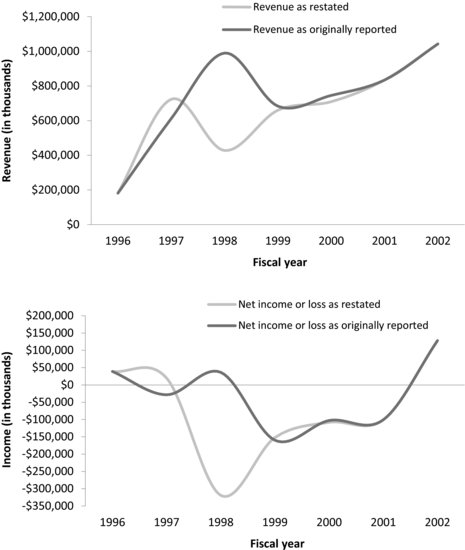

It is not possible to detect all of these misdeeds by reading through its financial statements because some items, such as the existence of a subsidiary to buy-back products, were never disclosed.9 But were there other clues to investors that there was something amiss?

- McAfee growth appears to be steady, but its primary competitor, Symantec, had slow revenue growth in 1998.

- Sudden reduction in prepaid accounts and a reduction in reserves for acquisitions in 1999.10

- Investments in other companies that then bought McAfee products, with the purchase of products close in value to the investment made by McAfee.11

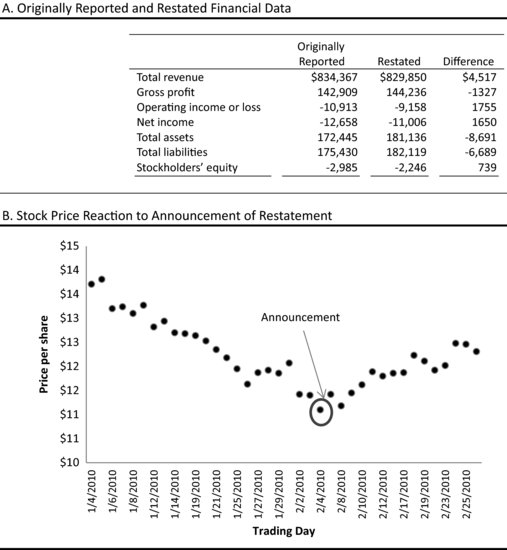

We provide McAfee's revenues and net income before and after the restatement in Exhibit 3.3. As you can see, if McAfee had not violated accounting principles, it would have reported falling revenues and a loss in 1998, rather than the increasing revenues and positive net income that it had reported. For its accounting misdeeds, McAfee restated its financial statements and paid a $50 million settlement.

Another example of channel stuffing is that alleged of ClearOne Communications, Inc. in 2001, in which the company forced distributors to take delivery of product that they did not want and then made verbal agreements for distributors to pay for the products as they sold them.12 Still another example is the case of Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, which settled a civil action in 2004 regarding channel-stuffing. In this case, the company was stuffing the channel near the end of each quarter in order to meet analysts' earnings estimates.13 In these cases, there was an increase in revenues and net income that was a sacrifice of future years' revenues and net income.

Extraordinary and Nonrecurring Items

In general, a company's earnings and cash flows should be generated from the operations of its business, rather than through nonrecurring means. A close examination of the sources of revenues in the income statement and notes may reveal nonoperating gains and losses. These nonoperating items are presented under various names, including “special,” “nonrecurring,” and “unusual.”

Nonrecurring items are the result of unusual events and are reported as part of operating expenses. For example, if a company that operates retail stores closes several of its stores, it would record a charge for the costs associated with these closings. As another example, a company that is on the losing side of a lawsuit would report the settlement or penalty as a nonrecurring charge against income.

A special type of nonrecurring item is the voluntary effect of a change in accounting principle. If the company changes an accounting principle in the current period, the company applies the change retrospectively, revising past earnings to reflect the effect in each period presented.14 If it is not practical to represent the cumulative effect of the change to earnings in the current or recent years (say, because the effect cannot be attributed to a particular year), the entire charge is presented in the balance sheet as an adjustment to shareholders' equity.15

Extraordinary items are defined as unusual and infrequent and are presented in the income statement after continuing operations and net of tax. There is a subtle distinction between nonrecurring items that are included in operating results and extraordinary items that are reported in the nonoperating portion of the income statement. These nonrecurring items are unavoidable and, with recent changes in accounting standards, may become more frequent. From the point of view of the analyst, these items are important in at least two respects:

In the 1980s and 1990s, many companies had significant restructuring charges and may have used these to manage earnings. However, some companies, such as International Business Machines (IBM), now consider restructuring charges part of their normal business and hence do not separate these changes as special.16

Further, many companies report nonrecurring and extraordinary items that have become quite ordinary, reporting gains and losses each year arising from these sources. This makes it difficult for the analyst to determine the result of the operations of the company and what is simply transitory.

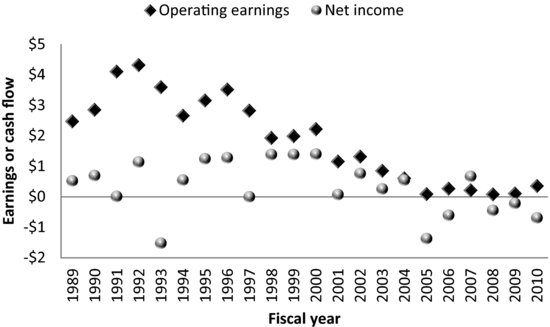

Consider the example of Eastman Kodak. We show Eastman Kodak's operating earnings and net income in Exhibit 3.4 over the period 1989–2011. We calculated operating earnings for this example as the difference between revenues and the sum of cost of goods sold, selling, general and administrative expenses, and research and development costs. The difference between operating earnings and net income is largely the result of nonrecurring charges including:

- Restructuring costs.

- Purchased in-process research and development.17

- Cumulative effect of a change in accounting principle.

- Other income and charges.

EXHIBIT 3.4 Comparison of Operating Earnings and Net Income, Eastman Kodak, 1989–2011

Source: Eastman Kodak 10-K filings, various years.

There are, of course, recurring charges, including goodwill amortization (in those years in which permitted), interest expense, and taxes, that result in a difference in these two series. Eastman Kodak had restructuring charges in 18 of these 23 years and in many of these years the charges made up the bulk of the difference between operating earnings and net income.18

Deferred Taxes

A large difference between reported income and taxable income may suggest the inclusion of revenues or expenses in the reported income that are not recognized for tax purposes in the current period. But examining the difference between accounting net income and taxable income is not possible because the tax returns are not made public. However, examining the sources and changes in deferred taxes—using notes to the financial statements—can provide some clues about how accounting and taxable income diverge.

Differences between income reported in the financial statements and taxable income arise from many sources, including differences in accounting for:

- Depreciation

- Installment sales

- Leases

- Warranties

- Pensions

It is quite common for companies to report a deferred tax liability or asset, and for this liability or asset to grow over time as the company's earnings and assets grow. What should catch the analyst's attention, however, is when the relationship between reported earnings and taxable income diverges significantly, as indicated by a significant change in the deferred tax liability or asset.

Goodwill Hunting

The accounting for the combination of companies from mergers and acquisitions is carried out using the purchase method, whereby the acquired company's assets are valued at fair value and any excess of the purchase price of the acquired company over this fair value is goodwill, an intangible asset.19

The purchase method requires that assets of the acquired company be revalued, but this is not a straightforward process because many assets, such as intangibles, do not have discernible market price. The possible consequences of using the purchase method include:

- Increased cost of goods sold as revalued inventory of the acquired company is sold.

- Goodwill created and reported as an asset on the balance sheet.

- Depreciation expense may be increased because of increased value for depreciable assets of the acquired company.

- Any debt discount resulting from a revaluation of debt must be amortized.

What is goodwill? Goodwill is the difference between the purchase price of the acquired company and the fair value of the acquired company's assets. If the difference is positive, as it is most often, the amount is recorded as an intangible asset. Each year, the surviving company evaluates the current balance in goodwill to determine its value. If the value is less than the carrying amount (i.e., the amount reported on the balance sheet), the asset is considered to have an impaired value and goodwill is written down to the current value.

Prior to 2002, companies amortized goodwill over a period not to exceed 40 years. The accounting principles changed with FASB, Statement of Financial Accounting Standard No. 142, that requires companies to test the goodwill annually for impairment.20 A write-down for impairment would hurt the earnings in the year of the write-down, but would result in improved returns on assets in the future years. This is because the write-down would not affect earnings in years beyond the write-down, yet would result in lower assets in the future years.

Many companies wrote off goodwill beginning in 2002, coinciding with a tough economic period, writing down goodwill during years in which earnings were low. For example, America Online, Inc., and Time Warner, Inc., merged in 2001, creating AOL-Time Warner Inc. With this merger, AOL-Time Warner created goodwill of approximately $99 billion, and wrote down $54.235 billion of goodwill in 2002—the year after this goodwill was “created” through the merger. In subsequent years, the returns on assets are slightly higher than they would have been if there was no write down (e.g., 2.73% with the write-down vs. 1.89% without the write-down).

For example, in 2003 and 2004, Yahoo! paid $2.9 billion to acquire other companies, $2.1 billion of which was allocated to goodwill and the rest was allocated to tangible assets and amortizable intangible assets (e.g., patents). In other words, more than 72% of what it paid for in these acquisitions could not be attributed to identifiable tangible or intangible assets. One of its acquisitions in 2003 was the $290 million paid for Inktomi, with only $49 million attributed to assets of Inktomi. Yahoo!'s goodwill increased to $4 billion by 2007, followed by Yahoo! recognizing goodwill impairment of $487.5 million in 2008.

The perplexing thing about goodwill is that it is really an intangible asset that is truly difficult to identify. If a company pays more for another company than what can be identified as tangible or intangible assets, what type of asset is this? Is it simply the amount by which one company has overpaid to acquire another company?

Of course, there are some companies that do not wish to take the earnings “hit” that a write-down in goodwill would entail.21 For example, the value of goodwill is most likely to decline during a recessionary economic environment. However, this is the environment in which companies may be hesitant to report a loss from goodwill impairment that, although a noncash event, would reduce reported net income.

In its study of goodwill impairment, Duff & Phelps—an independent provider of financial advisory services—found that:22

- Impairments are related to economic declines. For example, during the recent financial crisis, financial service companies had a larger proportion of impairments, compared to other industries.

- Impairments tend to follow a decline in performance, with investors anticipating goodwill impairments.

- Events that are likely to trigger impairment include legal or regulatory issues, changes in the economic climate, and changes in competition in the company's market.

TOO MANY CHOICES?

Accounting principles offer choices for companies' management because one method does not fit all companies. For example, Company A's assets may depreciate quickly, whereas Company B's may lose value by a constant amount each period. Therefore, allowing Company A and Company B to choose different methods to better represent their assets' depreciation results in a better quality of financial statement for both companies. However, when do choices become earnings management? This is one of the challenges of analysis.

Inventory Accounting

Choice of Method

The method chosen to account for inventory affects the value of inventory on the balance sheet, the cost of goods sold and earnings reported on the income statement, taxable income, and taxes. Therefore, the method affects not only the reported financial statements, but cash flows as well. There are three basic methods of accounting for inventory which differ in the assumptions regarding the cost flow of goods and cost of inventory remaining at the end of the period:

FIFO assumes that inventory items sold are the ones that have been in inventory the longest, so the cost of the older inventory items is recorded as the cost of goods sold, whereas LIFO assumes that any items sold are the ones that have been acquired recently, so the cost of the newer inventory items is recorded as the cost of goods sold. During a period of rising prices, LIFO produces an estimate of profit that is closest to the true profit, whereas during a period of falling prices, FIFO produces the more accurate estimate of profit. Depending on whether prices are rising or falling, the choice of inventory method affects the values reported in the financial statements:

| Comparing Amounts Reported Using FIFO and LIFO for: | During a Period of Rising Prices | During a Period of Falling Prices |

| Inventory on balance sheet | FIFO > LIFO | FIFO < LIFO |

| Cost of goods sold on income statement | FIFO < LIFO | FIFO > LIFO |

| Gross profit on income statement | FIFO > LIFO | FIFO < LIFO |

| Taxes | FIFO > LIFO | FIFO < LIFO |

The average cost method produces estimates that fall somewhere between the values produced by FIFO and LIFO.

The financial analyst must understand also how the choice of inventory method affects the volatility of operating earnings. If selling prices are less flexible than prices of materials, a company's profits will be more volatile with the FIFO method as compared to the LIFO method. As a further note, if a company reduces its inventory substantially during a period and uses LIFO accounting, there will be an artificial earnings boost from the sale of older, lower-priced inventory.

Because the method of inventory accounting affects the values shown in the financial statements, the financial analyst needs to know where to find the necessary information. In some cases, the company reports the method of inventory accounting in the balance sheet alongside the inventory account or, as is often the case, in the note that describes the company's accounting principles (usually Note 1). Additionally, if the company uses LIFO, an inventory note details the difference in inventory valuations if FIFO had been used if that difference is material. However, for companies using FIFO for inventory accounting, data necessary to convert FIFO into LIFO are not made available.

Companies in the same industry may use different methods of accounting for inventory, making comparisons among companies more difficult. Consider the household products industry. Colgate-Palmolive, Kimberly-Clark, and Procter & Gamble use both LIFO and FIFO in different proportions. Kimberly-Clark, for example, uses LIFO for U.S. inventories, but FIFO for non-U.S. inventories. Procter & Gamble, on the other hand, uses FIFO for most of their inventory, but uses LIFO for the cosmetics and commodities inventories. The variety in the use of inventory methods makes it challenging for the analyst.

Write-Downs

Companies are permitted to write-down the value of inventory when the carrying value exceeds the fair value of the inventory. Though healthy companies may experience the need to write-down inventory because of shifts in customer demand, questions arise:

- Is the company writing down inventory with the expectation of selling it at a higher profit in future periods?

- Is the company not writing down devalued inventory so that they do not dampen earnings?

Either of these cases would not be consistent with generally accepted accounting principles, but an analyst needs to ask the right questions in addressing the motive for the write-down.

Questions an analyst may ask about a write-down of inventory include the following:

- Is the company writing down its inventory on a timely basis?

- What changes in business have caused the loss in value of inventory?

- When the inventory is written down, does the company still have possession of the inventory? Will this inventory be sold in future periods?

There are cases of companies writing down inventory in one period and later selling this inventory at a higher profit margin in future periods. For example, the SEC alleges that Sunbeam Corporation wrote down the value of perfectly good inventory by $2.1 million in one year, only to sell this inventory in the next period for a $2.1 million greater profit.23 There are also cases in which a company did not write down inventory in a timely manner, resulting in an overstatement of earnings for the period.24

Depreciation

Methods of Depreciation

A company's depreciation expense can have an important effect on the firm's financial statements. Depreciation arises from the firm's investing activities, and it directly affects the firm's reported net income and asset values. The depreciation method and choice of useful life decisions affect the quality of earnings. For example, if assets are more productive in earlier years of their useful lives, the use of an accelerated method provides a higher quality of earnings relative to the use of the straight-line method.

Depreciation allocates the cost of the asset, less residual value, over the expected economic life of the asset. The economic life, also referred to as the useful life, is the number of years the asset is expected to be of use to the company. The residual value, also referred to as the salvage value, is the expected value of the asset at the end of its useful life. Depreciation thus provides a means for expensing the portion of the asset's cost that is expected to be used up during its life.

There are three classes of depreciation methods for financial reporting purposes. The first is straight-line depreciation, in which an equal amount of depreciation expense is taken each period of the asset's useful life. The second, referred to as accelerated depreciation, is more rapid depreciation than straight-line resulting in greater depreciation expense in the earlier years of an asset's life. The third class is units of production, whereby an estimate is made of the use of the asset (e.g., hours) and then the expense in any period reflects the usage in that period (e.g., number of hours used).

Over the life of the asset, the same amount of depreciation is expensed against income, no matter the method, as we demonstrated in Chapter 2. However for any given period it makes a difference on the financial statements as to which method a company uses. Accelerated methods produce higher depreciation expense in the earlier years, and hence lower earnings vis-à-vis the straight-line method. Accelerated methods also reduce the carrying value, shown on the company's balance sheet, faster in earlier years.

Most companies use straight-line depreciation for financial reporting purposes, though this does not mean that depreciation is directly comparable among companies because depreciable lives of assets may differ among companies. Limited information on depreciation methods and useful lives is provided in notes to the financial statements. The extent of this type of information varies widely.

Change in Estimates

The useful life and the salvage value of an asset are simply estimates. Companies review these estimates and occasionally change them—changing the depreciable life of an asset, whether lengthening or shortening the life, or changing the estimate of salvage value, affects the income statement and balance sheet, and hence the comparability of financial statements in different periods. A financial analyst must be aware of these changes and how they affect any comparisons overtime that are made for a given company.

When a company revises the depreciable life of an existing asset, for example, this is considered a change in accounting estimate. The company is required to account for the change in the period in which it occurs, but it is not permitted to restate prior period's financial accounts retroactively; in other words, the company makes a prospective disclosure, not a retrospective disclosure.25 The company is required to disclose the effect on income from continuing operations, net income, and any per-share effect.

Consider a company that is depreciating a $1 million asset, with a $100,000 salvage value, over 20 years. If the company revises the estimate of the useful life from 20 to 30 years in the eleventh year of the asset's life, this will lower the depreciation expense from $45,000 per year to $22,500 per year in year 11, resulting in higher earnings (by $22,500) for the years 11 through 20 than with the original estimate. This revision also affects the carrying value of the asset (i.e., cost less accumulated depreciation), as we show in Exhibit 3.5.

EXHIBIT 3.5 Example of the Balance Sheet Effect of a Revision in the Useful Life of an Asset

The recent change in accounting standards with respect to accounting changes should increase the transparency of financial statements with respect to these types of changes, though the disclosures are made only in the year of the change, not the subsequent years. Therefore, the analyst must consider how these changes affect the company's future years' profitability.

Pension Valuation Assumptions

A pension plan is an agreement under which an employer agrees to pay benefits to employees once the employee's period of service ends. A pension plan may either be a defined contribution plan, in which the employer makes only a specified contribution, or a defined benefit plan, in which a specific monetary benefit is promised. In the case of a defined benefit plan, these benefits depend on certain requirements specified by the employer, such as the employee's age and number of years of service.

The employer creates a pension fund, which is an intermediary used by the employer to meet the promised obligations. The employer makes payments to the fund and the fund invests these funds and makes pension payments to employees.

In terms of accounting for pension plans, defined contribution and defined benefit plans differ. In a defined contribution plan, accounting for the plan's obligation and assets is easy—the pension cost equals the contributions made and the employer reports an asset or liability reflecting the difference between actual payments made and the required payments. In the case of a defined benefit, the promised payments are not known with certainty and represent a liability because benefits will be paid in the future. In this case, the employer invests in assets, the plan assets, which are intended to pay off the expected pension liability. The unknowns are:

Companies report a pension expense on the income statement and a pension liability on the balance sheet. The pension expense is a result of a calculation that considers employees' earned pension benefits during the period, the time value of money, and the expected return on the pension plan's assets. In addition, companies are required to provide detail in a footnote to their financial statements with respect to the value of assets, the expected liability, and the assumptions used in these calculations, among other things. A recent change in accounting standards now requires companies to explain the basis for estimating the return on plan asset, the discount rate, and the rate of compensation increase (in the case of pay-related plans).27 These assumptions are important because they affect both the expense and the liability.28

It is important to understand just what a pension obligation is and how much of it shows up in the liabilities—and how much else there is that is not reported in liabilities. The pension liability that appears on the balance sheet may not be easy to find. To find the information we need, we must search the footnotes, but we have to know what we are looking for. Once in the footnotes, we have to sift through the various accounts. For example, there are three obligations that may be reported:

Our goal is to find the funding status, which is the difference between the projected benefit obligation (or accumulated benefit obligation if the pension obligation is not pay related) and the fair value of plan assets (i.e., the value of assets set aside to meet this obligation). Muddying the waters is the fact that when a company changes its plans, any change in costs is spread (i.e., amortized) over the remaining service life of employees. Though the accounting rules regarding disclosure were greatly improved in 2007, there remains some pension expense that slips by the income statement and goes directly to shareholders' equity.29

As an example of funding, Ford's pension obligation for U.S. plans as of 2011 was underfunded (i.e., the value of the plans' assets are less than the obligation) by $9.4 billion for the United States and $6 billion non-U.S. The funded status is negative (i.e., it is underfunded), which is represented as a component of accrued liabilities.30 Though Ford reported a 2011 pension expense of $900 million in the retirement benefits footnote, there was also a charge of $1.19 million to shareholders' equity for employee related benefits that is reported as a component of comprehensive income/(loss) for the year. Despite enhanced disclosures in pension benefits, the analyst must pull information from the statement of shareholders' equity, the accrued liabilities footnote, and the retirement benefits footnote.

Companies31 may revise the assumptions that they use in the calculation of the benefit obligation and the pension expense. These revisions, which are a change in an accounting estimate, affect the pension expense on the income statement and the liability (or asset) on the balance sheet. The effect each assumption has on the obligation and expense is as follows:

Therefore, if a company tends to use a low discount rate, a return on plan assets that is close to the discount rate, and a high rate of salary increase, it is conservative, and hence its earnings are of higher quality.

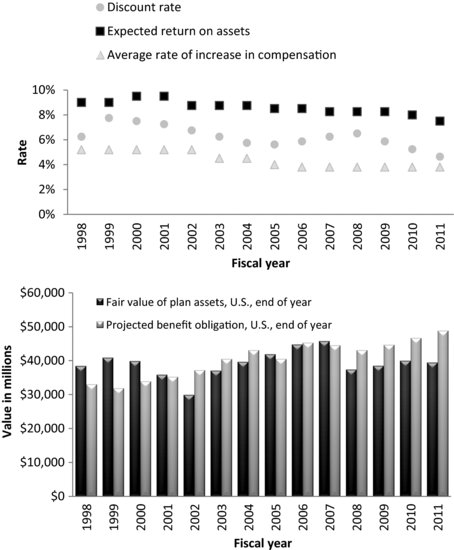

Looking at Ford's U.S. pension plan assumptions over time, as we show in Exhibit 3.6(A), we see that the assumptions have changed, most notably the discount rate. We provide the funding status and pension expense for each of these years in Exhibit 3.6(B). You can also see in Exhibit 3.6 that Ford's pension plan is underfunded in the years 2008–2011; that is, the benefit obligation exceeds the value of the pension assets.

EXHIBIT 3.6 Ford Motor Company U.S. Pension Plan

Sources: Ford Motor Company, 10-K filings, various years.

How do we interpret the effect of the change in the assumptions? The expected change in compensation is, for the most part, fixed by its union contract and, as you can see, was negotiated downward in 2003 and 2006. However, Ford can change its discount rate or its assumed return on assets. Consider the discount rate, which was revised downward through the period 1999 through 2004. If nothing else was changed, this would reduce the funding status (that is, make it worse) and increase the pension expense. So why did the pension expense go down in 1999 through 2001? Because the expected return on plan assets increased during this same period. In the 2003–2004 fiscal years, however, the expected return on assets was kept the same, yet both the discount rate and the rate of compensation increase declined; the net result was an increase in the pension expense.

So what's an analyst to do? Dig through the pension and retirement benefits footnote, ferret out the funding status, examine any changes in assumptions and how these affect both the pension expense and the funding status, and examine closely the company's explanation of those changes.

SO WHAT'S THEIR BUSINESS?

We tend to focus on the basic financial statements in evaluating a company's performance. However, we can learn a lot about a company by taking a look at the reporting on its business segments. Companies are required to report on its business segments, providing profit and loss, specific revenue and expense items, and assets attributed to the segment.32 Companies are also required to provide a discussion of how they determined a business segment.

There are two primary reasons for focusing on business segment results. First, in terms of making predictions for future periods, it is easier to make predictions for individual segments of a company than for a company as a whole because a company's segments' performance may be affected by different factors. Another reason for focusing on business segments is to assess the quality of earnings. If a company is deriving much of its profits from a business segment that is not its primary segment in terms of the company mission and investment of its assets, then this may suggest that the earnings of the company are not sustainable and/or of lower quality.

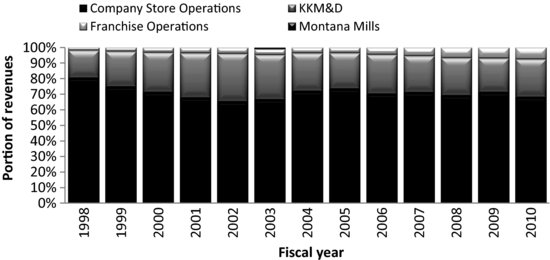

Consider the case of Krispy Kreme, the donut retailer and franchiser. Krispy Kreme went public in 1999 and was the darling of Wall Street as its stock soared. But as its stock soared, its financial condition soured. As we show in Exhibit 3.7, Krispy Kreme derived less of its income over time from its stores and franchise operations, and more from a segment named “KKM&D.” Taking a closer look at KKM&D in the management discussion and company description, you can see that KKM&D is the segment of Krispy Kreme that sells equipment to the franchisors. By requiring franchisors to purchase the equipment at substantial margins, Krispy Kreme has increased its revenues and profit. In fiscal year 2003, Krispy Kreme derived 32% of its operating income from equipment sales. However, this is short-lived because once the franchisors have purchased the equipment, this segment will not provide future profit and growth unless additional franchises are sold. As we show in Exhibit 3.7, the portion of revenues from KKM&D diminished in the years following 2003, but then increased to close to 36% of revenues in fiscal year 2010.33

EXHIBIT 3.7 Sources of Revenues for Krispy Kreme, 1999–2010

Source of data: Krispy Kreme, 10-K filings, various years.

RESTATEMENTS AND FINANCIAL ANALYSIS

Companies restate their financial results if there was an error in the previously reported results or the company is correcting financial results because of detected fraudulent reporting, a misinterpretation of accounting rules, or aggressive accounting that the company backs away from. For example, Office Depot announced in April 2011 that it was restating its 2010 fiscal year results. This restatement involved an interpretation of a tax loss carryback, and was of sufficient magnitude to change what was a profit to a loss.34

The General Accounting Office (GAO) examined over 1,000 restatements by publicly traded companies during the period 2002 through 2006.35 The most common reason for restatement in its analysis was related to costs and expenses, which is attributed to the increased emphasis on internal controls and quality of financial statements. Approximately 16% of companies disclosed a restatement during this period.

Another analysis of restatements, this one by Audit Analytics, examines restatements over a 10-year period.36 It provides results that indicate that the number of restatements per year have declined since 2006 and have declined in terms of the degree of restatement. However, “stealth” restatements have remained, and actually reached a peak in 2008. A stealth restatement is a restatement that is disclosed as part of a current financial filing with the SEC, instead of as a separate 8-K filing. Though the SEC is discouraging stealth restatements, they still occur.

The fact that there was an error should at least get the analyst's attention. Some errors result from a misunderstanding of the application of accounting principles. Some errors result from intentional misapplication of accounting principles. The analyst needs to take a close look at SEC filings to determine the reasons behind the restatement. Another reason to look at restatements is when using data to make predictions of future performance. The restated data should be more useful in making such predictions.

Consider the case of Overstock.com, Inc., which announced a restatement of its 2008 fiscal year results in February 2010. The company disclosed the restatement in their Form 12b-25, the Notification of Late Filing. In this filing, the company disclosed that there were numerous accounting errors.37

Do investors react to restatements? Yes, but the amount depends on the type of restatement.38 If the restatement relates to the integrity of the management, the market reaction is most severe. On the other hand, if the restatement is attributed to technical issues, the market reaction is small. The market reaction to Overstock.com's restatement, which was the third in three years, was minimal, as you can see in Exhibit 3.8(B).

EXHIBIT 3.8 Overstock.com, Inc.

Source of data: Overstock.com Inc., 10-K filings with the SEC; and Yahoo! Finance.

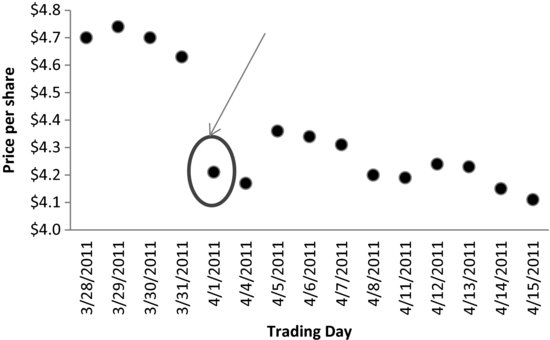

The market reaction to the Overstock.com restatement was not significant, but that is not the case with all restatements. The market reaction to Office Depot's announcement of a restatement of 2010 results after the close of trading on March 31, 2011, was a drop of approximately 10% on the following trading day, April 1, 2011, as we show in Exhibit 3.9.

EXHIBIT 3.9 Stock Market Reaction to Office Depot's Restatement Announcement March 31, 2011

Source of data: Yahoo! Finance.

TELL-TALE SIGNS

There are a number of tell-tale signs that can alert the analyst to actual or potential problems. These signs may be obvious, such as a qualification in an auditor's report, or may require a bit of digging into the numbers, such as an analysis of deferred taxes.

The Independent Auditor's Opinion

There are many caution flags that financial analysts may heed with regard to the company's independent auditor. In general, the independent accounting firm attests to the audit of the company's financial statements. There are several different possible results from the engagement of an auditor to review of the company's financial statements:

- An unqualified opinion. This is the good news. This means that the auditor believes that the financial statements are presented fairly in conformity with GAAP.

- A qualified opinion. This needs further research by the analyst. An auditor issues a qualified opinion when it believes that the financial statements present the company's financial position, results of operations, and cash flows in conformity with GAAP, except for some matter that remains qualified. This qualification will be spelled out in opinion and will relate to either the scope of the audit, a departure from GAAP, or doubt about the company continuing as a going concern.

- An adverse opinion. This is bad news. An auditor issues an adverse opinion when it believes that the financial statements do not present the company's financial position, results of operations, and cash flows in conformity with GAAP. This opinion is issued when there are significant departures from GAAP.

- A disclaimer of opinion. This is bad news too. The auditor issues this opinion when it is unable to form an opinion regarding the financial statements.

- A withdrawal of opinion(s). This is terrible news. In this case, the auditor is withdrawing previously issued opinions because of some egregious situation, such as suspected illegal activities by the audited company.

Most auditors' reports of publicly traded companies' financial statements are unqualified, which means that the auditor is stating that the financial statements are prepared according to generally accepted accounting principles and that these statements present fairly the results of operations. Occasionally, as the need arises because of changes in accounting principles, an unqualified report may have some explanatory language added. This type of explanation is the result of the changes in accounting principles and is generally not a cause for concern. But any time there is a qualification or any other type of opinion, the analyst must pay close attention.

Another caution flag is an unjustified change in independent auditors or a change in auditor that is the result of a disagreement with the auditor. Companies may change auditors for a number of reasons. The requirements imposed by the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 limit the nonaudit engagements of accounting firms, and hence a shuffling of companies among accounting firms to reduce the possible conflicts of interest related to nonaudit services is expected. However, auditor changes as a result of a disagreement are worth looking at.39

Consider the disagreement between Overstock.com and Grant Thornton in 2009. Grant Thornton was the auditor for less than one year for Overstock.com.40 The disagreements became a public squabble, and then were followed by restatements for accounting errors.

As a result of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, the management of public companies must now include in its annual report a report on the company's internal control over financial reporting. The Public Company Accounting Oversight Board has added this additional responsibility of auditors. This additional requirement is to attest to the management's assessment of the company's internal control over financial reporting. In attesting to the internal controls, the auditor expresses an opinion and notes whether there is a control deficiency, a significant deficiency, or a material weakness with respect to the internal controls.

Other Signs

There are a number of other warning signs that the financial analyst can look for in the financial information. We list several of these signs in Exhibit 3.10, though each may not be applicable for every company. For example, examining inventory changes for a company with relatively little inventory (e.g., Walt Disney Company) or examining receivable balances for a company that does not typically extend customer credit (e.g., Wal-Mart Stores) would not be fruitful.

EXHIBIT 3.10 Warning Signs

| Warning Sign | May Indicate | Where to Look |

| Change in auditor. | Disagreements concerning the application of GAAP. | Annual report's notes to financial statements and auditor's opinion. |

| Qualified auditor opinion. | Company is not a growing concern; auditor unable to examine all financial records. | Auditor's opinion in the annual report. |

| Unexplained changes in accounting policies. | Earnings management. | Annual report's accounting principles' note; significant change in account (e.g., depreciation expense). |

| An increasing gap between reported income and cash flow from operations. | Earnings management. | Annual report: Comparison of balances in deferred taxes and/or income tax note. |

| Unusual changes in inventories that do not coincide with changes in sales. | Inflation of sales. | Relationship of inventory (balance sheet) and sales (income statement) over time. |

| Unusual changes in accounts receivable that do not coincide with changes in sales. | Earnings management or inflated asset accounts in prior years. | Footnote on write-offs in annual report. |

| Large, unexpected asset write-offs. | Earnings management or inflated asset accounts in prior years. | Footnote on write-offs in annual report. |

| Large changes in deferred taxes on the balance sheet. | Changes in estimates of likelihood of reversals. | Tax footnote, focusing on changes in the valuation allowance. |

| Write-off of goodwill due to impairment. | Managing earnings through timing of impairment. | Write-off timing versus pattern of reported earnings. |

| Tendency to use financing mechanisms such as research and development partnerships. | Liabilities management. (possible understatement of obligations) or asset management (possible overstatement of assets). | Management discussion in annual report. |

| Warning Sign | May Indicate | Where to Look |

| Large change in discretionary expense, such as advertising and research and development. | Shifting expenses from one period to another. | Income statement and comparison of discretionary expenses over time. |

| Large fourth quarter adjustments. | Earnings management. | Quarterly income statement and balance sheet (e.g., comparison of fourth quarter results with prior year same quarter. |

| Related-party transactions. | Inflation of revenues or understatement of expenses if transactions are not arms-length. | Examine footnotes related to these charges. |

| Recurring and nonrecurring changes. | Earnings management. | Examine footnotes related to these charges. |

| Changes in assumptions of pension plans. | Management of pension liability and/or expense. | Retirement benefit plans footnote. |

The financial analyst must consider the company's history, the industry in which it operates, and the effects of the economy on the company when analyzing potentially troubling signs. Understanding the company's revenue and expense cycle is important in detecting subtle shifting of these items between periods. Understanding the changes in the company's industry is important for comparisons of the industry's conditions with those of the individual company (e.g., an industry-wide slow-down in customer payments). Understanding the economy and how the company may be affected by current conditions is important for detecting unusual changes in income or assets.

SUMMARY

The analysis of the financial condition and performance of a company requires understanding the quality of the financial data that is being analyzed. The management of a company has a great deal of room in selecting among accounting methods within the bounds of GAAP, though the changes resulting from the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 and the move toward convergence with Internal Financial Reporting Standards have resulted in fewer degrees of freedom. The analyst must understand the methods selected in order to make comparisons of financial data over time and among companies.

The many accounting choices that a company's management has available open up the possibility for management of earnings and make it more challenging to compare companies and to evaluate trends within a company over time. The devices that management may use include accruals management, revenue and expense recognition, and nonrecurring items. Financial results may also be affected by the impairment of goodwill, which results in a write-off of this intangible asset, reducing earnings in the period of the write-off and reducing total assets in future periods.

The different methods of accounting that a company's management may choose within generally accepted accounting principles creates opportunities to manage earnings, making the financial analyst job a bit more challenging. For example, different methods of accounting for inventory and depreciation may make a significant difference in reported asset values and earnings. A careful review of the company's accounting principles is useful in determining the types of adjustments the analyst must make to permit comparability.

Analysts need to examine the sources of a company's revenues and earnings. For example, a company that earns a large portion of its revenues from nonoperating sources or business segments that are not the primary lines of business may indicate potential problems in future earnings.

Analysts also need to be aware of companies' restatements of financial results. In the cases of errors and fraud, companies restate financial results for the periods affected. If we are assessing the market's reaction to financial reports, we would want to use the “as reported” information. On the other hand, as is often the case in financial analysis, we want to make forecasts concerning a company's future financial condition and performance, we should focus on the restated financial results.

An additional consideration for the financial analyst is the auditor's report. The independent accounting firm that audits a company's financial statements and reviews the management's reports on internal controls provides a statement regarding whether the financial statements are prepared according to generally accepted accounting statements and whether the internal controls for financial reporting are sufficient. Careful reading of these reports may reveal important information regarding the financial condition of the company.

REVIEW

1. See, for example,R. Watts and J. Zimmerman, “Positive Accounting Theory: A Ten-Year Perspective,” Accounting Review 65, no. 1 (1990): 131–156; and Katherine Shipper, “Commentary on Earnings Management,” Accounting Horizons 15, no. 4 (1989): 91–102.

2. Practice Alert 95-1 CPA Letter No. 1, “Revenue Recognition Issues,” AICPA CPA Letter (January 1995). Management of earnings for compensation purposes may result in (1) not recognizing income in periods of high earnings because of maximums in bonus plans; (2) large write-offs in years in which performance targets are not met because no bonus would be forthcoming for the period; and (3) speeding up recognition of revenues or delaying expenses to meet performance targets.

3. In academic research on earnings management, discretionary accruals are estimated from an examination of the historical difference between cash flows and net income; large deviations from the normal or typical relationship between cash flows and net income are interpreted as use of discretionary accruals.

4. A correlation ranges from –1 (perfect negative correlation) and +1 (perfect positive correlation). A correlation of zero indicates no linear relationship between the series.

5. Kodak's 2011 results included a net loss of $767 million, cash flow for operations of $998 million, and a shareholders' deficit of $2.35 billion.

6. John A. Byrne, “Al Dunlap Self-Destructed,” BusinessWeek, July 6, 1998, 58–64, www.businessweek.com/1998/27/b3585090.htm; and Martha Brannigan, “Sunbeam Concedes 1997 Statements May be Off,” Wall Street Journal, July 1, 1998, A4.

7. Securities and Exchange Commission v. McAfee, Inc., Civil Action No. 06-009, January 4, 2006. www.sec.gov/litigation/litreleases/lr19520.htm

8. McAfee Corporation was acquired by Intel for almost $8 billion in 2011.

9. McAfee's management executed transactions that affected appearances. For example, aware that analysts watched days sales outstanding, McAfee sold accounts receivables for cash, but retained responsibility for collection and made sure to pay the banks in full despite its casual arrangements with distributors for delayed payments or cash in place of discounts.

10. According to the EC, this was to increase sales returns reserves and inflate revenues.

11. The SEC referred to these investments as “sham” transactions.

12. Securities and Exchange Commission v. ClearOne Communications, Inc., Frances M. Flood, and Susie Strohm, Civil No. 2 103 CV 55 DAK.

13. Securities and Exchange Commission v. Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Civil Action No. 04-3680 (D.N.J.), filed August 4, 2004.

14. This is prescribed by FASB, Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 154, which is in effect previous to Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 154, a company would report the cumulative effect of the accounting change as a charge against earnings in the income statement.

15. A retrospective change in earnings due to an accounting change is not the same thing as a restatement of earnings. Restatements are due to errors or fraud, not changes in accounting principle.

16. Prior to 1994, IBM routinely reported substantial restructuring charges each year. Since 1994, however, the company no longer breaks these items out separately.

17. The charges for purchased research and development are the result of a write-off of a portion of the purchase price in an acquisition. When one company acquires another company, some of the purchase price may be allocated to the intangible asset of “in-process research and development.” Then once the companies are combined, this purchased research and development is written off.

18. The large deviation in 1993 between operating earnings and net income was due to a $2.168 billion effect from a change in accounting principle. The large deviation in 2005 relates, primarily, to accelerated depreciation related to restructuring.

19. FASB, Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 141, “Business Combinations,” June 30, 2001.

20. FASB, Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 142, “Goodwill and Other Intangible Assets,” December 31, 2001, which is now referred to as Accounting Standards Codification Topic 350.

21. Enron did not write-down impaired assets and it was found to have falsely represented the company's financial statements because of this (United States Securities and Exchange Commission v. Kenneth Lay, Jeffrey K. Skilling, Richard A. Causey, Civil Action No. H-04-0284).

22. Duff & Phelps, 2010 Goodwill Impairment Study, Financial Executives Research Foundation, October 2010, www.duffandphelps.com/sitecollectiondocuments/reports/dnp003_goodwill_impairments_report_12.pdf

23. SEC, Accounting and Auditing Enforcement Release No. 1393, “In the Matter of Sunbeam Corporation.”

24. SEC, Securities Exchange Act of 1934 Release No. 48441, “In the Matter of Gerber Scientific, Inc., Respondent,” April 8, 2004; and SEC, Accounting and Auditing Enforcement Release No. 1987, April 8, 2004, Administrative Proceeding File No. 3-11455.

25. FASB, Statement of Financial Accounting Standards, No. 154, “Accounting Changes and Error Corrections,” December 15, 2005.

26. This issue regarding the return on asset assumption was highlighted by Warren Buffett in a speech at the end of 2001, published in Fortune. He stated that “Unfortunately, the subject of pension assumptions, critically important though it is, almost never comes up in corporate board meetings.… And now, of course, the need for discussion is paramount because these assumptions that are being made, with all eyes looking backward at the glories of the 1990s, are so extreme. I invite you to ask the CFO of a company having a large defined-benefit pension fund what adjustment would need to be made to the company's earnings if its pension assumption was lowered to 6.5%. And then, if you want to be mean, ask what the company's assumptions were back in 1975 when both stocks and bonds had far higher prospective returns than they do now.” Buffett goes on to warn corporate management that too high a return on plan assets risks litigation for the CFO, the board, and the auditors.

27. FASB, Statement of Financial Accounting Standards, No. 132, revised 2003, “Employers' Disclosures about Pensions and Other Postretirement Benefits,” December 15, 2003.

28. For a more extensive discussion of pension accounting and its importance in corporate valuation, see Ronald Ryan and Frank J. Fabozzi, “Pension Fund Crisis Revealed,” Journal of Investing 12 (Fall 2003): 43–48; and Frank J. Fabozzi and Ronald J. Ryan, “Redefining Pension Plans,” Institutional Investor, January 2005, 84–89.

29. For example, unrealized pension costs do not appear on the income statement as a subtraction to arrive at net income; rather, they reduce accumulated other comprehensive income, which goes directly to shareholders' equity.

30. Ford Motor Company 2011 10-K Filing, Note 17.

31. Actually, the effect on the expense is mixed because it affects both the service cost and the interest cost. However, the net effect is generally directly related to the direction of the discount rate change.

32. FASB, Statement of Financial Accounting Standards, Statement No. 131, “Disclosures about Segment of an Enterprise and Related Information,” December 15, 1997.

33. For the fiscal year ending January 30, 2011, KKM&D, now referred to as the KK Supply Chain segment, generated $30 million of Krispy Kreme's $41 million operating income (per footnote 16 of Krispy Kreme's fiscal 2010 10-K filing).

34. In Office Depot's amended 10-K filing for fiscal year 2010, a $33.3 million profit was restated to a $46.2 million loss (Note B of the 10-KA filing for fiscal year ending December 25, 2010).

35. GAO, Financial Restatements: Update of Public Company Trends, Market Impacts, and Regulatory Enforcement Activities, July 2006, amended March 5, 2007.

36. Mark Cheffers, Don Whalen, and Olga Usvyatsky, 2009 Financial Restatements: A Nine Year Comparison, Audit Analytics, February 2010. www.complianceweek.com/s/documents/AARestatements2010.pdf

37. The announcement in February 2010 was the third time this company had announced accounting errors in three years.

38. Cheffers, Whalen, and Usvyatsky, 2009 Financial Restatements: A Nine Year Comparison, Audit Analytics Trend Reports, February 2010.

39. There is evidence, both academic and anecdotal, that in the pre–Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 world, auditors may have bent under pressures from audit clients and may actually be complicit in the fraudulent acts of these audit clients. See, for example, Debra Jeter, Paul Chaney, and Pam Shaw, “The Impact on the Market for Audit Services of Aggressive Competition by Auditors,” Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 22, no. 6 (2003): 487–516.

40. The auditor from 2001 to 2009 was PricewaterhouseCoopers, Grant Thornton from March to November 2009, and then KPMG became the auditor in December 2009.