CHAPTER 1

Introduction

The investments arena is large, complex, and dynamic. These characteristics make it interesting to study, but also make it challenging to keep up. What changes? Laws and regulations, the introduction of new types of securities, innovations in markets and trading, company events (such as the passing of the CEO or a settlement of a lawsuit), and a persistently changing economy to name a few. Add to this mix the political, technological, and environmental changes that occur throughout the world every day, and you have quite a task to understand investment opportunities and investment management.

There is a wealth of financial information about companies available to financial analysts and investors. The popularity of the Internet as a source of information has made vast amounts of information available to everyone, displacing print as a means of communication. Consider the amount of information available about Microsoft Corporation. Not only can investors find annual reports, quarterly reports, press releases, and links to the companies' filings with regulators on Microsoft's web site, anyone can download data for analysis in spreadsheet form and can listen in on Microsoft's management's conversations with analysts.

The availability and convenience of information has eased the data-gathering task of financial analysis. What remains, however, is the more challenging task of analyzing this information in a meaningful way. Recent scandals involving financial disclosures increase the importance of knowing just how to interpret financial information. In response to these scandals, Congress passed the Sarbanes-Oxley (SOX) Act of 2002, which increases the responsibility of publicly traded corporations, accounting firms performing audits, company management, and financial analysts.1 And while this Act is an attempt to restore faith in financial disclosures, investors and analysts must still be diligent in interpreting financial data in a meaningful way.

This need for diligence is evident in the financial crisis of 2007–2008, which tested analysts' and investors' abilities to understand complex securities and their accounting representation. The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank Act) passed in 2010 in response to the crisis, added requirements pertaining to corporate governance, security regulation, the regulation of the financial services industry, and consumer protections.2 And, while there will likely be additional disclosures of some of the more complex instruments as a result of this act, financial instruments are constantly evolving, and analysts and investors have to stay abreast of these innovations and their implications for analysis.

The purpose of this book is to assist the analyst and investor in understanding financial information and using this information in an effective manner.

WHAT IS FINANCIAL ANALYSIS?

Our focus in this book is on financial analysis, which is the selection, evaluation, and interpretation of financial data and other pertinent information to assist in evaluating the operating performance and financial condition of a company. The operating performance of a company is a measure of how well a company has used its resources—its assets, both tangible and intangible, to produce a return on its investment. The financial condition of a company is a measure of its ability to satisfy its obligations, such as the payment of interest on its debt in a timely manner.

Financial reporting is the collection and presentation of current and historical financial information of a company. This reporting includes the annual reports sent to shareholders, the filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) for publicly traded companies, and press releases and other reports made by the company. Financial analysis takes that information—and much more—and makes sense out of it in terms of what it says about the company's past performance and condition and, more importantly, what it says about the company's future performance and condition.

The financial analyst must determine what information to analyze (e.g., financial reports, market information, economic information) and how much information (5 years? 10 years?) to review. The analyst must sift through the vast amount of information, selecting the information that is most important in assessing the company's current and future performance and condition. A part of this analysis requires the analyst to assess the quality of the information. Though publicly traded companies must report their financial information according to generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), there is still some leeway that the reporting company has within these principles. The analyst must understand the extent of this leeway and what this implies for the company's future performance.

The analyst has many tools available in the analysis of financial information. These tools include financial ratio analysis and quantitative analysis. The key to analysis, however, is understanding how to use these tools in the most effective manner.

What happens if we're not looking closely at financial information? Lots. Several of the scandals that arose in the past few years were actually detectable using basic financial analysis and common sense. It is not possible to spot all cases of fraud and manipulation, but there are some telltale signs that should raise caution flags in analysis. Examples of these signs include:

- Revenue growth that is out of line with others in the same industry or not reasonable given the current economic climate.

- Profits that are increasing at a much faster rate than cash flows generated from operations.

- Debt disappearing from the balance sheet.

Example: Enron

Consider Enron Corporation, which filed for bankruptcy in 2001 following a financial-reporting scandal. Enron's revenues grew from a little over $9.1 billion to over $100 billion in the 10-year period from 1995 through 2000 as we show in Exhibit 1.1; in other words, its revenues grew at an average rate of over 61% per year. During this period, Enron's debts grew too, from 76% of its assets to over 82% of its assets. Enron experienced significant growth and reported significant debt, becoming one of the largest corporations in the United States within 15 years of becoming a publicly traded corporation.

An interesting aspect of Enron's growth is that the company produced revenues far in excess of what other companies of similar size could produce. For example, in 2000, Enron produced over $5 million in revenues per employee, whereas Exxon Mobil could only produce $2 million per employee and General Electric only $0.4 million per employee.3

Enron became embroiled in an accounting scandal that involved, in part, removing debt from its balance sheet into special purpose entities. While the scandal proved shocking, Enron had actually provided information in its financial disclosures that hinted at the problems. Enron disclosed in footnotes to its 2000 10-K filing that it had formed wholly owned and majority-owned limited partnerships “for the purpose of holding $1.6 billion of assets contribute by Enron.” [Enron 10-K, 2000] The result?

The most notorious deal involved Joint Energy Development Investment Limited Partnership II (JEDI II). Enron executives created this partnership using Enron funds and loans fed through Chewco Investments. Though accounted for as a special purpose entity (SPE), and hence its assets and liabilities were removed from Enron's balance sheet, there was insufficient independent ownership of the entity to qualify JEDI II as a SPE because Chewco was, essentially, Enron.4

In all of this, keep in mind that Enron left a trail for the analyst to find in the filings of Enron and these entities. The limited partnerships and their relation to Enron were reported in the footnotes to Enron's filings and in other filings with the SEC. Not all the pieces were there, but enough to raise concerns.

Example: AIG

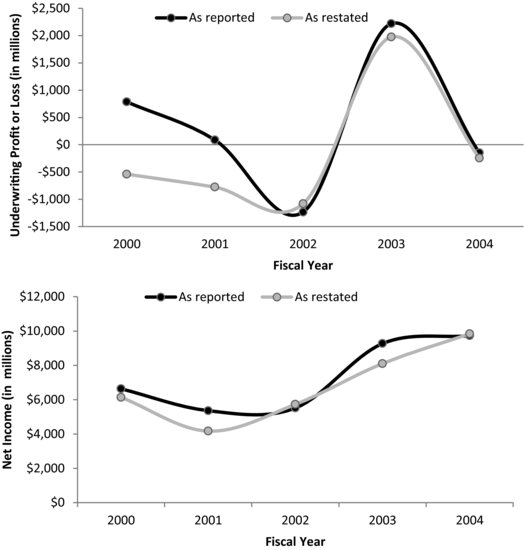

As another example, consider AIG, an insurance company that settled a case of fraud in 2010 after six years for $725 million. Along with anticompetitive charges and stock price manipulation, AIG was accused of accounting manipulations perpetrated between 1999 and 2005 that inflated its claims reserves by reporting what was, essentially, a deposit with a reinsurance company as a reinsurance transaction.5 The result of this inflation represented that it had more assets available to meet claims than it actually had, making itself look more profitable and less risky. As you can see in Exhibit 1.2, AIG reported underwriting profits instead of losses in 2000 and 2001, which then overstated net income, especially in 2000 and 2001.

Were there bread crumbs to follow? A few. First, AIG was known for its opaque accounting:

It's been an open secret for years on Wall Street that no one outside the company really understood its accounting. AIG has long been called “opaque” on Wall Street, which is what analysts say when they can't figure out a company's books because much of the detail is off the books.6

Second, reinsurance accounting at the time was murky, so the arrangement with General Re, which involved an unusual insurance product that increased AIG's loss reserves to acceptable levels, should have raised questions. The particular ‘insurance’ product itself was unusual.

A typical insurance product involves the insurance company receiving a periodic premium to insure for a particular type of loss (e.g., some sort of casualty). If a loss does not occur, the insurance company comes out ahead; if a loss event occurs, the insured is protected from loss by the insurance company. The AIG contract was a bit different: A multiyear insurance contract, with the premium up front that would cover most or all of the potential losses, with any unused premium refunded at the end of the contract. This AIG product is more of a loan than it is an insurance contract, which would require different accounting. However, AIG reported the proceeds from this product as insurance, not as a loan.7

Following the bread crumbs should have at least raised concerns about the financial performance and financial condition of AIG. And opaque accounting should be a significant crumb to follow.

WHERE DO WE FIND THE FINANCIAL INFORMATION?

There are many sources of information available to analysts and investors. One source of information is the company itself, preparing documents for regulators and distribution to shareholders. Another source is information prepared by government agencies that compile and report information about industries and the economy. Still another source is information prepared by financial service firms that compile, analyze, and report financial and other information about the company, the industry, and the economy.

The basic information about a company can be gleaned from publications (both print and Internet), annual reports, and sources such as the federal government and commercial financial information providers. The basic information about a company consists of the following:

- Type of business (e.g., manufacturer, retailer, service, utility).

- Primary products.

- Strategic objectives.

- Financial condition and operating performance.

- Major competitors (domestic and foreign).

- Degree of competitiveness of the industry (domestic and foreign).

- Position of the company in the industry (e.g., market share).

- Industry trends (domestic and foreign).

- Regulatory issues (if applicable).

- Corporate governance.

- Economic environment.

- Recent and planned acquisitions and divestitures.

A thorough financial analysis of a company requires examining events that help explain the company's present condition and effect on its future prospects. For example, did the company recently incur some extraordinary losses? Is the company developing a new product, or acquiring another company? Current events can provide useful information to the analyst.

A good place to start is with the company itself and the disclosures that it makes—both financial and otherwise. Most of the company-specific information for a publicly traded company can be picked up through company annual reports, press releases, and other information that the company provides to inform investors and customers. Information about competitors and the markets for the company's products must be determined through familiarity with the products of the company and its competitors. Information about the economic environment can be found in many available sources. We take a brief look at the different types of information in the remainder of this chapter.

WHO GETS WHAT TYPE OF INFORMATION AND WHEN?

Disclosures Required by Regulatory Authorities

Companies whose stock is traded in public markets are subject to a number of securities laws that require specific disclosures. We list several of these securities laws in Exhibit 1.3. Publicly traded companies are required by these securities laws to disclose information through filings with the SEC, the federal agency that administers federal securities laws.

EXHIBIT 1.3 Federal Regulations of Securities and Markets in the United States

| Law | Description |

| Securities Act of 1933 | Regulates new offerings of securities to the public; requires the filing of a registration statement containing specific information about the issuing corporation and prohibits fraudulent and deceptive practices related to security offers. |

| Securities and Exchange Act of 1934 | Establishes the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to enforce securities regulations and extend regulation to the secondary markets. |

| Investment Company Act of 1940 | Gives the SEC regulatory authority over publicly held companies that are in the business of investing and trading in securities. |

| Investment Advisers Act of 1940 | Requires registration of investment advisors and regulates their activities. |

| Federal Securities Act of 1964 | Extends the regulatory authority of the SEC to include the over-the-counter securities markets. |

| Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 | Wide-ranging law that creates the Public Accounting Oversight Board, requires auditor independence, increases corporate responsibility for financial disclosures, enhances financial disclosures, and extends the authority of the SEC. |

| Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 | Broad law that encompasses changes in the regulation and oversight of the financial services industry, the markets for derivatives, investor protections, credit rating agencies, executive compensation, and mortgages and other lending. |

The SEC, established by the Securities and Exchange Act of 1934, carries out the following activities:

- Issues rules that clarify securities laws or trading procedure issues.

- Requires disclosure of specific information.

- Makes public statements on current issues.

- Oversees self-regulation of the securities industry by the stock exchanges and professional groups such as the National Association of Securities Dealers.

As you can see in Exhibit 1.3, a publicly traded company must make a number of periodic and occasional filings with the SEC. In addition, major shareholders and executives must make periodic and occasional filings. We list a number of these filings in Exhibit 1.4. Company filings to the SEC are available free, in real-time, from the SEC's EDGAR website, at www.sec.gov.

EXHIBIT 1.4 Summary of Filings of Publicly Traded Companies, Their Owners, and Executives

| Statement | Purpose | Information |

| 10-K report | Annual disclosure of financial information required of all publicly traded companies; due 90 days following the company's fiscal year-end. | Description of the company's business, financial statement data found in the company's annual report, notes to the financial statements, and additional disclosures including a management discussion and analysis. |

| 10-Q report | Quarterly disclosure by publicly traded companies; required 45 days following the end of each of the company's first three fiscal quarters. | A brief presentation of quarterly financial statements, notes, and management's discussion and analysis. |

| 8-K filing | Filed to report unscheduled, material events or events that that may be considered of importance to shareholders of the SEC. | Description of significant events that are of interest to investors and are filed as these events occur. |

| Prospectus | Filing made by a company intending to issue securities; registration statement complying with the Securities Act of 1933; | Basic company and financial information of the issuing company. |

| Proxy statement (Schedule 14A)a | Issued by the company pertaining to issues to be put to a vote by shareholders; complies with Regulation 14A; circumstances that are required for a vote are determined by state law. | Description of issues to be put to a vote; management's recommendations regarding these issues; compensation of senior management; shareholdings of officers and directors. |

| Registration statements (e.g., S-1, S-2, F-1) | A registration statement is a filing made by a company issuing securities to the public; required by the 1933 Act. | Financial statement information as well as information that describes the business and management of the firm. |

| Statement | Purpose | Information |

| Schedule 13D | Filing made by a person reporting beneficial ownership of shares of common stock of a publicly traded company such that the filer's beneficial ownership is more than 5% of a class of registered stock; filed within 10 days of the shares' acquisition. | Report of an acquisition of shares, including information on the identity of the acquiring party, the source and amount of funds used to make the purchase, and the purpose of the purchase. |

| Schedule 14D-1 | Filing for a tender offer by someone other than the issuer such that the filer's beneficial ownership is more than 5% of a class of registered stock. | Report of an offer to buy shares including information on the identity of the acquiring party, the source and amount of funds used to make the purchase, the purpose of the purchase, and the terms of the offer. |

| aThere are different types of proxy: preliminary, confidential, and definitive. The most common is the definitive proxy, generally indicated with the abbreviation DEF (e.g., DEF 14A). | ||

The SEC, by law, has the authority to specify accounting principles for corporations under its jurisdiction. The SEC has largely delegated this responsibility to the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). While recognizing the FASB Accounting Standards Codification as authoritative, the SEC also issues accounting rules, often dealing with supplementary disclosures.8 Therefore, the financial information provided in the company's 10-K filing is more comprehensive than that provided in its annual report provided to shareholders.

Form 10-K

The Form 10-K filing contains the information provided in the annual report (that is, balance sheet, income statement, statement of cash flows, statement of stockholders' equity, and footnotes), plus additional disclosures, such as the management discussion and analysis (MDA). For most large corporations, the 10-K must be filed within 60 days after close of a corporation's fiscal year.9 We provide a list of the required disclosures for Form 10-K in Exhibit 1.5, as identified using the SEC's numbering system of requirements. The disclosure requirements in the 10-K have changed over time as the SEC seeks additional information from companies regarding risk, internal controls, and the company's auditing firm.

EXHIBIT 1.5 Required Disclosures of the Form 10-K Filing

| Part I

1. Business

2. Properties

3. Legal proceedings

4. Submission of matters to a vote of security holders

|

| Part II

5. Market for registrants common equity, related stockholder matters, and issue purchases of equity securities

6. Selected financial data

7. Management's discussion and analysis of financial conditions and results of operations

7A.Quantitative and qualitative disclosures about market risk

8. Financial statements, and supplementary data

9. Changes in and disagreement with accountants on accounting and financial disclosure

9A. Controls and procedures

9B. Other information

|

| Part III

10. Directors and executive officers

11. Executive compensation

12. Security ownership of certain beneficial owners and management and related stockholder matters

13. Certain relationships and related transactions

14. Principal accounting fees and services

15. Exhibits and financial statement schedules

|

The MDA is generally viewed as an important disclosure, providing additional transparency of financial statements. In the MDA, which is Item 7 of a company's 10-K filing, the company's management provides a discussion of risks, trends, unusual or infrequent events, and uncertainties that pertain to the company and is a useful device for management to explain the financial results in terms of the company's strategies, recent actions (e.g., mergers) and the company's competitors. We summarize the Item 7 items in Exhibit 1.6.

EXHIBIT 1.6 Required Discussion in Item 7 of the 10-K MD&A

|

1. Liquidity

2. Capital resources

3. Known material trends

4. Results of operations, including unusual or infrequent events or economic changes, known trends and uncertainties, discussion of any material change in revenues, and impact of inflation

5. Off-balance sheet arrangements, including the business purpose and importance

6. Contractual obligations, including leases

|

In addition, the company's management must provide a discussion of significant components of revenues and expenses that are important in understanding the company's results of operations. The MDA also provides information that may help reconcile previous years' financial results with the current year's results. The MDA must also provide additional information about off-balance sheet arrangements, as well as a table that discloses contractual obligations.10 As a result of rulemaking arising from the

Dodd-Frank Act, companies are required to disclose additional information, including information on liquidity, capital resources, and short-term borrowing.

Form 10-Q

A similar form, Form 10-Q, must be filed within 35 days after close of a corporation's fiscal quarter.11 This filing is similar to the 10-K, yet there is much less detailed information, as you can see in Exhibit 1.7.

EXHIBIT 1.7 Required Disclosures of the Form 10-Q Filing

| Part I

1. Financial statements

2. Management's discussion and analysis of financial conditions and results of operations

3. Quantitative and qualitative disclosures about market risk

4. Legal proceedings

5. Controls and procedures

1. Legal proceedings

2. Unregistered sales of equity securities and use of proceeds

3. Defaults upon senior securities

4. Submission of matters to a vote of security holders

5. Other information

6. Exhibits

|

Form 8-K

The 8-K statement is an occasional filing that provides useful information about the company that is not generally found in the financial statements. A company files the 8-K statement within four business days of the event. There are currently 22 specific events for which a company is required to file the 8-K statement, as we detail in Exhibit 1.8.12 Previous to the SOX Act and the resulting SEC rules, the company was required to file an 8-K for any of eight events. The SOX Act shifted four additional requirements from the 10-K disclosures and added eight additional events.

EXHIBIT 1.8 Events Requiring Discloser of 8-K

Proxy Statement

In addition to the financial statement and management discussion information available in the periodic 10-Q and 10-K filings, companies provide useful non-financial information in proxy statements. The proxy statement is the company's notification to the shareholders of matters to be voted upon at a shareholders' meeting. The proxy statement provides an array of information on issues such as:

- The reappointment of the independent auditor.

- Compensation (salary, bonus, and options) of the top five executives and the stock ownership of executives and directors.

- Detailed information about proposals subject to a vote by the shareholders.

Other Filings

In addition, when a corporation offers a new security to the public, the SEC requires that the corporation prepare and file a registration statement. The registration statement presents financial statement data, along with detailed information about the new security. A condensed version of this statement, referred to as a prospectus, is made available to potential investors.

Documents Distributed to Shareholders

The objective of financial reporting is to provide information that is useful to present and potential investors and creditors and other users in making rational investment, credit, and similar decisions.13

With that objective in mind, the financial reports prepared and distributed by the company should help users in assessing “the amounts, timing and uncertainty of prospective net cash inflows of the enterprise.”14 Therefore, the financial reports to shareholders are not simply a presentation of the basic financial statements—the balance sheet, the income statement, the statement of cash flows, and the statement of stockholders' equity—but also a devise to communicate additional nonfinancial information, such as information about the relevant risks and uncertainties of the company. To that end, recent changes in accounting standards have broadened the extent and type of the information presented within the financial statements and in notes to the financial statements. For example, companies are now required to disclose risks and uncertainties related to their operations, how they use estimates in the preparation of financial statements, and the vulnerability of the company to geographic and customer concentrations.15

The annual report is the principal document used by corporations to communicate with shareholders. It is not an official SEC filing; consequently, companies have significant discretion in deciding on what types of information is reported and the way it is presented. The annual report presents the financial statements, notes to these statements, a discussion of the company by management, the report of the independent accountants, and financial information on operating segments, product and services, geographical areas, and major customers.16 Along with this basic information, annual reports may present 5- or 10-year summaries of key financial data, quarterly data, and other descriptions of the business or its products.

Quarterly reports to shareholders provide limited financial information on operations. These reports are simpler and more compact in presentation than their annual counterparts. In addition to the annual and quarterly reports, companies provide information through press releases using the services of commercial wire services such as

- Reuters (www.reuters.com)

- PR Newswire (www.prnewswire.com)

- Business Wire (www.businesswire.com)

- First Call (www.firstcall.com)

- Dow Jones (www.dowjones.com)

The wire services then distribute this information to print and Internet media. The information provided in press releases includes earnings, dividends, new products, and acquisition announcements.

Issues

There are a number of issues that should be considered in using the financial statement data provided in company annual and quarterly reports. We discuss many of these issues in later chapters that focus on financial analysis, cash flow analysis, and earnings quality.

Consider the following examples:

- The restatement of prior years' data.

- The different accounting standards used by non-U.S. companies.

- There may be “off-balance sheet” activity.

The Restatement of Prior Years' Data

When a company reports financial data for more than one year, which is often the case, previous years' financial data is restated to reflect any changes in accounting methods or acquisitions that have taken place since the previous data had been reported. Consider a company that restates its 2010 income statement when it changes an accounting method in 2011. If, for example, the analyst were looking at the company and its competitive position in 2010, the analyst would want to use the as-reported 2010 data. If, on the other hand, the analyst is looking at trends in some of the data in an effort to forecast future performance or conditions, the restated 2010 data is more appropriate.

The Different Accounting Standards Used by Non-U.S. Companies

Another concern is dealing with financial statements of non-U.S. reporting entities. There are several reasons for this concern. First, as of this writing, there are no internationally acceptable standards of financial reporting. This includes not only the accounting methods that are acceptable for handling certain economic transactions and the degree of disclosure, but other issues. Specifically, there is no uniform treatment of the frequency of disclosure. Some countries require only annual or semiannual reporting rather than quarterly as in the United States.

There is an effort to “harmonize” accounting standards around the world, to make statements more comparable. The International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) and the FASB are working toward the development of international accounting standards. In addition, the IASB and the FASB have agreed to produce joint pronouncements regarding new accounting standards. Beginning January 1, 2005, most companies listed in the European Union (EU) were required to prepare their financial statements according to the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), which are promulgated by the IASB. The adoption of IFRS, along with the convergence of the standards of IASB and FASB, are significant strides toward consistent international accounting standards.17

There May Be “Off-Balance Sheet” Activity

There is always some investment or financing activity that simply does not show up in financial statements. Though there have been improvements in accounting standards that have moved much of this activity to the financial statements (e.g., leases, pension benefits, postretirement benefits, asset retirement obligations), opportunities remain to conduct business that is not represented adequately in the financial statements. An example is the case of joint ventures. As long as the investing corporation does not have a controlling interest in the joint venture, the assets and financing of the venture can remain off of the balance sheet. Limited information is provided in notes to the statements, but this information is insufficient to adjudge the performance and risks of the joint venture.

The opportunity to keep some information from the financial statements places a greater burden on the financial analyst to dig deep into the company's notes to the financial statements, filings with the SEC, and the financial press.

Interviewing Company Representatives

Interviewing representatives of a company may produce additional information and insight into the company's business. The starting place for the interview is the company's investors' relations (IR) office, which is generally well prepared to address the analyst's questions.

The key is for the analyst to do his or her homework before meeting with the IR officer so that the interview questions can be well focused. This preparation includes understanding the company's business, its products, the industry in which it operates, and its recent financial disclosures. The analyst must understand the industry-specific terminology and any industry-specific accounting methods. In the telecommunications industry, for example, the analyst must understand measures such as gigahertz and minutes-in-use, and such terms as bandwidth, point-of-presence, and spectrum.18 As another example, an analyst for the oil and gas industry should understand that a degree-day is a measure of temperature variation from a reference temperature.

The analyst must keep in mind that the IR officer has an obligation to treat all investors in a fair manner, which means that the IR officer cannot give a financial analyst material information that is not also available to others. There is also information that the IR officer cannot give the analyst. For example, in a very competitive industry it may not be appropriate to give monthly sales figures for specific products. The analyst must understand the competitive nature of the industry and understand what information is typically not revealed in the industry.

Because the analyst comes armed with knowledge of the company's financial statements, the questions should focus on taking a closer look at the information provided by these disclosures:

- Extraordinary or unusual revenues and expenses.

- Large differences between earnings from cash flows.

- Changes in how data is reported.

- Explanations for deviations from consensus earnings expectations.

- How the company values itself versus the market's valuation.

- Sales to major customers.

An analyst that uses a statistical model to develop forecasts for the company or its industry may, of course, require very specific data that may not be readily available in the financial statements.

It is sometimes useful to determine what the company expects to earn in the future. Though companies may be reluctant to provide a specific earnings forecast, they will sometimes respond to a query regarding analysts' consensus earnings forecasts. In their response about analysts' forecasts, the company may reveal their own forecast. If a company provides a forecast of its earnings, the analyst must consider the forecast in light of the company's previous forecasting; for example, some companies may consistently underestimate future earnings in order to avoid a negative earnings surprise. Further, the company's forecast or response to a consensus forecast might be accompanied by significant defensive disclosures that concern the risks that the company may not meet projected earnings.

Regulation FD

In an attempt to “level the playing field,” the SEC in 2000 adopted new rules regarding selective disclosure.19 These rules, in the form of the Fair Disclosure regulation, are referred to as Regulation FD. Basically, if a publicly traded company or anyone acting on its behalf makes material, nonpublic information available to certain persons, the company must make a public disclosure of this information. All intentional disclosures must be made simultaneously to the public. If someone makes an unintentional disclosure, the company is required to make a prompt, public disclosure of the information.

Information Prepared by Government Agencies

Federal and state governmental agencies provide a wealth of information that may be useful in analyzing a company, its industry, or the economic environment.

Company-Specific Information

One the most prominent innovations in the delivery of company information is the SEC's Electronic Data Gathering and Retrieval (EDGAR) system that is available on the Internet (www.sec.gov). The EDGAR system provides on-line access to most SEC filings for all public domestic companies from 1994 forward. The EDGAR system provides real-time access to filings, providing up-to-date information accessible to everyone.

In addition to the EDGAR system at the SEC site, several financial service companies provide free or fee access to the information in the EDGAR system in different database forms that assist in searching or database creation tasks.20

Industry Data

The analysis of a company requires that the analyst look at the other firms that operate in the same line of business. The purpose of examining these other companies is to get an idea of the market in which the company's products are sold: What is the degree of competition? What are the trends? What is the financial condition of the company's competitors?

Several government agencies provide information that is useful in an analysis of an industry. The primary governmental providers of industry data are the U.S. Bureau of the Census and the Bureau of Economic Analysis, an agency of the U.S. Department of Commerce. A recent innovation is the creation of Stat-USA, a fee-based collection of governmental data. Stat-USA is an electronic provider of industry and sector data that are produced by the U.S. Department of Commerce. The available data provided for different industries include gross domestic product, shipments of products, inventories, orders, and plant capacity utilization.21

The government classification of businesses into industries is based on the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS).22 NAICS is a system of industry identification that replaced the Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) system in 1997, though many analysts and data providers continue to use the SIC system.23 The NAICS is a six-digit system that classifies businesses using 350 different classes. The broadest classification comprises the first two digits of the six-digit code and is listed in Exhibit 1.9. The NAICS is now the basis for the classification of industry-specific data produced by governmental agencies. Like the SIC system before it, the NAICS will, over time, become the basis for the classification of companies for industry-specific data used by nongovernmental information providers as well.

EXHIBIT 1.9 North American Industry Classification System Sector Codes

| Code | NAICS Sectors |

| 11 | Agriculture, Forestry, Fishing and Hunting |

| 21 | Mining |

| 22 | Utilities |

| 23 | Construction |

| 31–33 | Manufacturing |

| 42 | Wholesale Trade |

| 44–45 | Retail Trade |

| 48–49 | Transportation and Warehousing |

| 51 | Information |

| 52 | Finance and Insurance |

| 53 | Real Estate and Rental and Leasing |

| 54 | Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services |

| 55 | Management of Companies and Enterprises |

| 56 | Administrative and Support, Waste Management and Remediation Services |

| 61 | Education Services |

| 62 | Health Care and Social Assistance |

| 71 | Arts, Entertainment, and Recreation |

| 72 | Accommodation and Foodservices |

| 81 | Other Services (except Public Administration) |

| 92 | Public Administration |

| Source: U.S. Census Bureau, www.census.gov/epcd/www/naics.html. | |

Economic Data

Another source of information for financial analysis is economic data, such as the gross domestic product and consumer price index, which may be useful in assessing the recent performance or future prospects of a firm or industry. For example, suppose you are evaluating a firm that owns a chain of retail outlets. What information do you need to judge the firm's performance and financial condition? You need financial data, but they do not tell the whole story. You also need information on consumer spending, producer prices, and consumer prices. These economic data are readily available from government sources, a few of which we list in Exhibit 1.10.

EXHIBIT 1.10 Examples of Government Sources of Economic Data

| Publisher | Web Sources | Print or CD-RomProduct |

| Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System | www.bog.frb.fed.us | Federal Reserve Bulletin |

| Bureau of Economic Analysis | www.bea.doc.gov | National Product Accounts Business Inventories Gross Product by Industry |

| Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, FRED II | research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/ | |

| Stat-USA | www.stat-usa.gov | National Trade Data Bank |

| U.S. Census Bureau | www.census.gov | CenStats |

| U.S. Department of Commerce | www.doc.gov | Survey of Current Business |

Information Prepared by Financial Service Companies

A whole industry exists to provide financial and related information about individual companies, industries, and the economy. The ease and low cost of providing such data on the Internet has fostered a proliferation of information providers. However, the prominent providers in today's Internet-based world are some of the same providers that were prominent in print medium.

Company-Specific Information

Information about an individual company is available from a vast number of sources, including the company itself through its own web pages. In addition to relaying the company's financial information that is presented by the company through its communication with shareholders and regulators, there are many financial service firms that compile the financial data and present analyses.

We list several sources of data on individual companies in Exhibit 1.11. This is by no means an exhaustive listing because of the large and ever-growing number of information providers. The providers distinguish themselves in the market for information through the breadth of coverage (in terms of the number of companies in their data base), the depth of coverage (in terms of the extensive nature of their data for individual companies), or their specialty (e.g., the collection of analyst recommendations and forecasts). These resources are available online, some free and some fee-based.

EXHIBIT 1.11 Sources of Individual Company Financial Data

Just what data are used to analyze an industry depends on the particular industry. We provide examples of industry-specific data in Exhibit 1.12.

EXHIBIT 1.12 Examples of Industry-Specific Factors

| Industry | Factor(s) | Explanation |

| Advertising | Gross billings | Total dollar amount of revenues from advertising. |

| Air transport | Load factor | Percentage of seats sold. |

| Aircraft manufacturer | Backlog | Number of aircraft ordered for production not completed. |

| Banking/Credit | Loan origination | Dollar amount of loans made. |

| Loan loss provision | Percentage of loans considered being bad debt. | |

| Cards in force | Number of credit cards outstanding. | |

| Electric Utility | Load factor | Average of the percentage of total capacity used. |

| Retail | Same-store sales | Revenues of the same store in a previous period. |

| Savings and Loan | Interest cost to gross income | Percentage of interest paid on deposits to total gross income. |

| Semi-conductor | Book-to-bill ratio | Ratio of orders to completed orders. |

| Telecommunications | Cost per access line | Ratio of operating cost to number of lines of service. |

A number of financial information providers offer industry-specific data and compile financial data by industry. Some services, such as Standard & Poor's Compustat, SNL Financial, and Value Line, provide industry data based on their large universe of companies covered in their database of individual company financial data.

Economic Data

Much of the economic data that are used in financial analysis are taken from government sources, though some information is independently produced through surveys and research.

There are many commercial services that collect and disseminate this and other information. These services include:

- AP Business News (www.ap.org)

- Thomson Reuters (www.reuters.com)

- Business Wire (www.businesswire.com)

The following financial publications provide economic data in both in print and electronic forms:

- Wall Street Journal (www.wsj.com)

- Investors.com (www.investors.com)

- Financial Times (www.ft.com)

In addition, databases, such as the HIS Global Insight (www.ihs.com), offer historical series of economic and financial data.

Government and organizations' databases provide economic data, including:

- Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis' FRED system (research.stlouisfed.org/fred2)

- U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (www.bea.gov)

- World Bank (data.worldbank.org)

- International Monetary Fund (IMF) (www.imf.org)

- Eurostat (ec.europa.eu/Eurostat/)

The continued globalization of financial systems results in the growing availability of economic and financial data.

WHAT DOES SARBANES-OXLEY MEAN TO COMPANIES AND INVESTORS?

The financial scandals that arose recently created problems in terms of the public's confidence in the capital markets, companies' financial disclosures, and the reliance on the auditing by public accounting firms. In response to this lack of confidence, the Sarbanes-Oxley (SOX) Act of 2002 was passed in mid-2002.24 The SOX act has changed the landscape with respect to financial disclosures, corporate governance, auditing, and penalties for financial misdeeds. We provide a list of key provisions that affect financial analysis of companies in Exhibit 1.13.

EXHIBIT 1.13 Key Provisions of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002

| Title I | Public Company Accounting Oversight Board

|

| Title II | Auditor Independence

|

| Title III | Corporate Responsibility

|

| Title IV | Enhanced Financial Disclosures

|

| Title V | Analyst Conflicts of Interest

|

| Title VIII | Corporate and Criminal Fraud Accountability

|

| Title IX | White-Collar Crime Penalty Enhancements

|

| Title XI | Corporate Fraud and Accountability

|

Auditors

The role of the auditing accounting firm is to attest to whether the client company is providing financial statements that are prepared consistent with generally accepted accounting principles. Consider the Supreme Court of the United States opinion in the case of United States v. Arthur Young:This “public watchdog” function demands that the accountant maintain total independence from the client at all times and requires complete fidelity to the public trust. … Public faith in the reliability of a corporation's financial statements depends upon the public perception of the outside auditor as an independent professional. … If investors were to view the auditor as an advocate for the corporate client, the value of the audit function itself might well be lost.25

The establishment of an oversight board for accounting firms and the requirements pertaining to auditor independence are in response to the problems encountered when the relationship between the auditor and the audit client becomes too close, inhibiting the audit firm from being the “public watchdog” of the client's compliance with generally accepted accounting principles. Consider the case of Enron Corporation discussed earlier in this chapter. In 2000, the year before the scandal erupted, Enron paid its auditing accounting firm a total of $52 million in fees: $25 million for audit services and $27 million for consulting services.26

Corporate Responsibility

There are a number of provisions in the SOX act that affect the responsibilities of publicly traded corporations and build upon previous attempts to strengthen the role of the audit committee, which is a committee comprised of members of the company's board of directors.27 The SOX act provisions affect the corporate governance with respect to the composition of the audit committee that has responsibilities related to financial reporting, monitoring choices of accounting policies, monitoring the internal control process, and overseeing the engagement and performance of the auditors.

In addition to the enhanced role of the audit committee, the SOX act and subsequently issued rules prohibit insider trading during a pension blackout period.28 A blackout period is a period of time in which participants in a participant-directed pension plan cannot trade employer securities. This is, again, a response to problems observed at firms involved in scandals in which the executives were able to sell their stock in the company before the company's demise, but other employees were not able to do so.29

Financial Disclosures

Financial disclosures were enhanced in three ways with the SOX act. First, more information must be disclosed regarding off-balance sheet transactions. Second, companies are required to reconcile pro forma financial information with financial information determined using generally accepted accounting principles. Pro forma results are financial statement information, such as earnings, that are calculated by the company using their own creative approach to accounting.30

In addition, companies must now make disclosures regarding the corporation's governance, such as whether there is a financial expert on the audit committee, and whether there is a code of ethics for financial officers. Further, there are greater restrictions on loans to executives.

Analysts

There is a potential for a conflict of interest in the case of financial analysts that are employed by firms that perform investment banking functions. One of the important functions of an investment banking firm is to help companies bring stock and bond issues to the market, providing capital for corporations. If the investment banking part of the company is not sufficiently independent of the financial analysts of the same company, who may be making stock or bond recommendations, there is a potential for biased ratings on the stock or bond issue.

The goal of the analyst provisions in the SOX act, among other actions taken by the SEC, is to insure that there is no link between the investment banking and the financial analyst functions within a company.31

Accountability

There are a number of deterrents to financial fraud included in the SOX act. There are criminal penalties included for defrauding shareholders, destroying documents, false certification of financial reports, and mail fraud. There is also increased protection of whistleblowers. Many of the expanded criminal penalties are the direct result of recent scandals.

WHAT DOES THE DODD-FRANK ACT MEAN FOR COMPANIES AND INVESTORS?

We summarize the provisions of the 2010 financial reform act by section in Exhibit 1.14. Much of the act focuses on the stability of the financial system, especially in an attempt to prevent a similar, significant financial crisis that affects the economy to the extent of the 2007–2008 financial crisis. Titles I, II, III, V, VI, and XI of this act focus primarily on changes in the regulation of financial services firms. The act is designed to end the government bailouts for firms that are “too big to fail” by requiring institutions to have more capital (which acts as a safety-net), identifying troubled institutions in advance, and providing for a liquidation of a troubled financial institution.

EXHIBIT 1.14 Key Provisions in the Dodd-Frank Act

| Title I | Financial Stability Creates the Financial Stability Oversight Council, which has members representing the primary financial regulators, including the Treasury, the Federal Reserve, the Comptroller of the Currency, and the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Creates the Office of Financial Research, which analyzes and reports on the financial services industry, especially those firms that may have a significant effect on the economy. |

| Title II | Orderly Liquidation Authority Establishes the FDIC as the primary authority for liquidating a troubled financial institution. Advised by the Financial Stability Oversight Council. |

| Title III | Transfer Power to the Comptroller, the FDIC, and the Federal Reserve Dissolving the Office of Thrift Supervision, transferring its responsibilities to other regulators. |

| Title IV | Regulation of Advisers to Hedge funds and Others Increase reporting of investment advisors. Redefines “accredited investor.” Requires studies on accredited investor requirements, self-regulatory authority for private funds, and short selling. |

| Title V | Insurance Creates the Federal Insurance Office, which monitors insurance companies and coordinates with state regulators. |

| Title VI | Improvements to Regulation Reduces the participation of banking institutions in hedge funds and private equity funds. |

| Title VII | Wall Street Transparency and Accountability Increases the regulation of credit derivatives. Requires that swaps are cleared through an exchange or clearinghouse. |

| Title VIII | Payment, Clearing, and Settlement Supervision Requires the Federal Reserve to create standards to manage systemic risk. |

| Title IX | Investor Protections and Improvements to the Regulation of Securities Creates Office of Investor Advocate. Increases disclosures for individual investors in financial products. Enhances whistleblower programs. Increases regulation of credit rating firms. Increases the risk assumed by parties securitizing assets. Increases disclosure on executive compensation and provides shareholder vote on compensation tri-annually. |

| Title X | Bureau of Financial Protection Creates the Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection within the Federal Reserve System, charged with research, consumer financial education, and consumer protection. |

| Title XI | Federal Reserve System Created new position, the Vice Chairman for Supervision, on the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Increases responsibility of the Federal Reserve to develop and monitor standards pertaining to risk management and liquidity. |

| Title XII | Improving access to Mainstream Financial Institutions Increase participation of low- and middle-income individuals in the banking system. |

| Title XIII | Pay it Back Act Requires that funds not used or returned in the Troubled Asset Relief Program [TARP] be used to offset the federal deficit. |

| Title XIV | Mortgage Reform and Anti-predatory Lending Act Reform the mortgage lending process, enhancing standards for lending and appraisals. Provides minimum underwriting standards for all home mortgages. Requires development of programs to assist existing high-risk home mortgage borrowers. |

| Title XV | Miscellaneous Includes unrelated provisions for mine safety, conflict mineral mining, loans issued by the International Monetary Fund, and other issues. |

| Title XVI | Section 1256 contracts Exclude swaps and other specified derivatives from capital gain or loss tax provisions that require mark-to-market for non-dealers. |

Titles IV, VII, IX and XII are intended to protect individual investors and borrowers, by more closely regulating the providers of financial products, financial service providers, and credit ratings. The creation of the Office of Financial Research will likely result in more data available to evaluate firms in the financial services industry by providing metrics, research, and stress test results of financial service firms, among other things. There is also increased regulation of credit-rating agencies by the SEC, including additional public disclosures about credit rating decisions. This should result in more information to investors and creditors about not only the rated companies, but also about the ratings process.

A controversial provision relates to executive compensation. The law requires the disclosure to shareholders of the relation between executive compensation and performance, as well as the relation between the compensation of the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) and the median compensation of all other employees. The purpose of this provision is to give shareholders additional power to affect compensation.

The remaining titles are dedicated primarily to “housekeeping” provisions that deal with unspent emergency bailout funds, and other matters.32 Though implementation of the act is still on-going and elements of the act may be adjusted with legislation, the provisions that affect the financial analysis of a company are likely to continue the trend towards increased disclosure of publicly traded companies.

SUMMARY

Financial analysis is the selection, evaluation, and interpretation of financial data and other information with the objective of formulating forecasts of future cash flows of a company. Financial analysis is different from financial reporting; financial reporting conveys past and current financial information, whereas financial analysis is forward-looking. A challenge of financial analysis is to sort through the wealth of information and develop a meaningful analysis of a company.

Companies prepare and distribute information for regulators and shareholders. This information includes annual and quarterly financial reports (e.g., 10-K, 10-Q). Additional information may be gathered from 8-K filings, company press releases, proxy statements, and through interviewing a company's representatives. Government agencies and commercial services prepare and disseminate information about individual companies, industries, and the economy.

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 has changed financial reporting and disclosures through additional disclosure requirements and through enhanced penalties for financial misconduct. The SOX act has also changed the responsibilities of the company's audit committee, as well as the relation with the auditor. In addition, this act has provisions that require the independence of the financial analyst from any investment banking functions of the analyst's employer.

The Dodd-Frank Act was a reaction to the financial crisis of 2007–2008 and is intended to increase disclosures and to provide regulators with the tools necessary to identify entities facing financial difficulties that are “too big to fail” and to forestall another crisis of these proportions.

A key lesson from the issues that inspired the SOX Act and the Dodd-Frank Act is that analysts and investors must keep up with innovations in financial instruments, transactions, and disclosures.

REVIEW

1. Public Law 111-203, H.R. 4173, July 21, 2010, www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-107publ204/pdf/PLAW-107publ204.pdf

2. Public Law 107-204, 116 Stat. 745, July 30, 2002, www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-107publ204/pdf/PLAW-107publ204.pdf

3. This dimension was pointed out by Dan Ackman. “Enron The Incredible,” Forbes, January 15, 2002, www.forbes.com/2002/01/15/0115enron.html.

4. The keys for accounting that would remove the SPE from the balance sheet are the requirement that at least 3% of the equity capital of the SPE be owned by independent parties, and that an investor other than Enron exercises control over the entity. Other names for an SPE include special purpose vehicle (SPV), conduit, or transformer.

5. A reinsurance company is an insurance company that insures an insurance company. The reinsurance company in this case was General Re. This follows a $10 million penalty in 2003 for inflating its balance sheet in a case brought by the SEC and the U.S. Justice Department, and does not include other settlements and penalties for other issues.

6. Jim Jubak, “At AIG, The Real Mess Is Far From Over,” Jubak's Journal, The Street, April 13, 2005 www.thestreet.com/story/10217149/1/aigs-real-mess-is-far-from-over.html.

7. An executive of AIG and four executives of General Re were convicted of fraud in 2008 for the scheme to manipulate loss reserves, a fraud that the SEC estimated cost investors $1.4 billion (Securities and Exchange Commission v. Ronald Ferguson, Elizabeth Monrad, Christian Milton, Robert Graham and Christopher Garand, February 2, 2006; and Litigation Release No. 21235, October 1, 2009).

8. Prior to July 1, 2009, the standards were referred to as the FASB Statements of Financial Accounting Standards (SFAS).

9. The deadline was 90 days after the fiscal year prior to the SEC's RIN (Regulation Identifier Number) 3235-AI33, “Acceleration of Periodic Report Filing Dates and Disclosure Concerning Website Access to Reports,” November 15, 2002. The revised deadline of 60 days was phased in over three years and applies to issuers with a public float of at least $75 million.

10. SEC, RIN3235-AI170, “Disclosure in Management's Discussion and Analysis about Off-Balance Sheet Arrangements and Aggregate Contractual Obligations,” April 7, 2003.

11. SEC, RIN 3235-AI33, “Acceleration of Periodic Report Filing Dates and Disclosure Concerning Website Access to Reports,” November 15, 2002.

12. SEC, RIN3235-AI46, “Additional form 8-K Disclosure Requirements and Acceleration of Filing Date,” August 23, 2004. Under the previous rule, the SEC required 8-K filings for disclosure of nine different events. The 2002 rule added eight additional events that require 8-K disclosure and shifted four disclosure requirements from the 10-K and 10-Q disclosures. In addition, any other event that the company deems important to shareholders may be reported using an 8-K filing. Because 8-K filings are triggered by major company events, it is useful for the analyst to keep abreast of any such filings for the companies that they follow.

13. FASB, Financial Accounting Concept 1, Objectives of Financial Reporting by Business Enterprises (Stamford, CT 1978).

14. Ibid.

15. Accounting Standards Executive Committee, Statement of Position 94-6, “Disclosure of Significant Risks and Uncertainties,” 1994; effective for fiscal years beginning after December 15, 1995.

16. FASB, Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 131, “Disclosures about Segments of an Enterprise and Related Information,” June 1997.

17. We discuss the IFRS and compare it with U.S. GAAP in Chapter 2.

18. Association for Investment Management and Research, The Telecommunications Industry (Charlottesville, VA, 1994), 108–110.

19. SEC, RIN 3235-AH82, “Selective Disclosure and Insider Trading,” October 23, 2000. www.sec.gov/rules/final/33-7881.htm

20. These services include EDGAR Online (www.edgar-online.com) and EDGAR from Compustat (www.compustat.com).

21. Web access to this data is available through the Department of Commerce site (www.doc.gov), Stat-USA (www.stat-usa.gov), and the Census Bureau (www.census.gov).

22. This classification system is the result of the joint efforts of the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the U.S. Census Bureau, Statistics Canada, and Mexico's Instituto Nacional de Estadistica, Geografia e Informatica (INEGI).

23. The SIC system was developed by the Office of Management and Budget and had been in use since the 1930s.

24. Public Law 107-204, 116 Stat.745, July 30, 2002, www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-107publ204/pdf/PLAW-107publ204.pdf.

25. United States v. Arthur Young & Co., et al., 465 U.S. 805 (1984).

26. Enron Corporation's definitive proxy, DEF 14A, filed March 28, 2001, 11.

27. Previous movements to strengthen the role of the audit committee include the Treadway Commission, which was the National Commission on Fraudulent Financial Reporting.

28. SEC, RIN3235-AI171, “Insider Trades During Pension Fund Blackout Periods,” January 23, 2003.

29. Many Enron employees had the majority of their retirement savings in Enron stock prior to the scandal. Making matters worse was that while Enron's stock fell, the 401(k) plan was “locked down” during a pension “blackout period,” prohibiting those over 50 years of age from selling their shares. However, this prohibition did not apply to the company's executives. As the stock was falling from around $90 per share to less than $1 a share following the news of the scandal, most Enron employees had lost the vast majority of their retirement savings. The executives, many of whom sold their stock prior to the stock's bottom price, took home millions of dollars.

30. For example, Trump Hotels & Casinos Resorts, Inc. released earnings results for 1999 that selectively included some information (a one-time gain), but excluded other information (a one-time charge) (SEC, Accounting and Auditing Enforcement Release No. 1499, January 16, 2002; and SEC, Administrative Proceeding File No. 3-10680).

31. An example is Merrill Lynch, which settled with the SEC, paying $100 million in 2002, in a case that involved an analyst who gave high ratings to a stock of a company that was an investment banking client of the firm. However, in private emails that same analyst did not believe that the stock was of high quality.

32. These are funds that were part of the federal Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) used to purchase assets from financial institutions.