9

PROPERTY, PLANT AND EQUIPMENT

INTRODUCTION

Long‐lived tangible and intangible assets (which include property, plant and equipment as well as development costs, various intellectual property intangibles and goodwill) hold the promise of providing economic benefits to an entity for a period greater than that covered by the current year's financial statements. Accordingly, these assets must be capitalised rather than immediately expensed, and their costs must be allocated over the expected periods of benefit for the reporting entity. IFRS for long‐lived assets address matters such as the determination of the amounts at which to initially record the acquisitions of such assets, the amounts at which to present these assets at subsequent reporting dates and the appropriate method(s) by which to allocate the assets' costs to future periods. Under current IFRS, the standard allows for a choice between historical cost and revaluation of long‐lived assets.

Long‐lived non‐financial assets are primarily operational in character (i.e., actively used in the business rather than being held as passive investments), and they may be classified into two basic types: tangible and intangible. Tangible assets, which are the subject of the present chapter, have physical substance. Intangible assets, on the other hand, have no physical substance. The value of an intangible asset is a function of the rights or privileges that its ownership conveys to the business entity. Intangible assets, which are explored at length in Chapter 11, can be further categorised as being either (1) identifiable, or (2) unidentifiable (i.e., goodwill), and further subcategorised as being finite‐life assets and indefinite‐life assets.

Long‐lived assets are sometimes acquired in non‐monetary transactions, either in exchanges of assets between the entity and another business organisation, or else when assets are given as capital contributions by shareholders to the entity. IAS 16 requires such transactions to be measured at fair value, unless they lack commercial substance.

It is increasingly the case that assets are acquired or constructed with an attendant obligation to dismantle, restore the environment or otherwise clean up after the end of the assets' useful lives. Decommissioning costs have to be estimated at initial recognition of the asset and recognised, in most instances, as additional asset cost and as a provision, thus causing the costs to be spread over the useful lives of the assets via depreciation charges.

Measurement and presentation of long‐lived assets after acquisition or construction involve both systematic allocation of cost to accounting periods and possible special write‐downs. Concerning cost allocation to periods of use, IFRS requires a “components approach” to depreciation. Thus, significant elements of an asset (in the case of a building, such components as the main structure, roofing, heating plant and elevators, for instance) are to be separated from the cost paid for the asset and amortised over their various appropriate useful lives.

When there is any diminution in the value of a long‐lived asset, IAS 36, Impairment of Assets, should be applied in determining what, if any, impairment should be recognised.

This Standard shall be applied in accounting for property, plant and equipment except when another Standard requires or permits a different accounting treatment.

Property, plant and equipment specifically exclude the following:

- Property, plant and equipment classified as held for sale (refer to Chapter 13).

- Biological assets related to agriculture activities, other than bearer plants (refer to Chapter 31).

- Recognition and measurement of exploration and evaluation assets (refer to Chapter 32).

- Mineral rights and mineral reserves such as oil, natural gas and similar non‐generative resources (refer to Chapter 32).

| Sources of IFRS | ||

| IFRS 5, 8 | IAS 16, 36, 37 | IFRIC 1, 17, 18 |

DEFINITIONS OF TERMS

Bearer plant. This is a living plant that has all of the following characteristics; it is used to supply or produce agricultural products; it will provide output for a period greater than one year and for which the possibility of it being sold as agricultural produce is remote.

Carrying amount. Carrying amount of property, plant and equipment is the amount at which an asset is recognised after deducting any accumulated depreciation and accumulated impairment losses.

Cost. Amount of cash or cash equivalent paid or the fair value of the other consideration given to acquire an asset at the time of its acquisition or construction or, where applicable, the amount attributed to that asset when initially recognised in accordance with the specific requirements of other IFRS standards (e.g., IFRS 2, Share‐Based Payment).

Depreciable amount. Cost of an asset or the other amount that has been substituted for cost, less the residual value.

Depreciation. The process of allocating the depreciable amount (cost less residual value) of an asset over its useful life.

Fair value. The price that would be received to sell an asset or paid to transfer a liability in an orderly transaction between market participants at the measurement date (see Chapter 25).

Impairment loss. The excess of the carrying amount of an asset over its recoverable amount.

Property, plant and equipment. Tangible assets that are used in the production or supply of goods or services, for rental to others or for administrative purposes and that will benefit the entity during more than one accounting period. Also referred to as fixed assets.

Recoverable amount. The greater of an asset's fair value less costs to sell or its value in use.

Residual value. Estimated amount that an entity would currently obtain from disposal of the asset, net of estimated costs of disposal, if the asset were already of the age and in the condition expected at the end of its useful life.

Useful life. Period over which an asset is expected to be available for use by an entity, or the number of production or similar units expected to be obtained from the asset by an entity.

RECOGNITION AND MEASUREMENT

An item of property, plant and equipment should be recognised as an asset only if two conditions are met: (1) it is probable that future economic benefits associated with the item will flow to the entity, and (2) the cost of the item can be determined reliably. Spare parts and servicing equipment are usually carried as inventory and expensed as consumed. However, major spare parts and standby equipment may be used during more than one period, thereby being similar to other items of property, plant and equipment. The 2011 Improvements Project amended IAS 16 to clarify that major spare parts and standby equipment are recognised as property, plant and equipment if they meet the definition of property, plant and equipment, failing which they are recognised as inventories under IAS 2, Inventories.

There are four concerns to be addressed in accounting for long‐lived assets:

- The amount at which the assets should be recorded initially on acquisition;

- How value changes after acquisition should be reflected in the financial statements, including questions of both value increases and possible decreases due to impairments;

- The rate at which the assets' recorded value should be allocated as an expense to future periods; and

- The recording of the ultimate disposal of the assets.

Initial Measurement

The standard has not prescribed any specific unit of measure to recognise property, plant and equipment. Thus, judgement may be applied in determining what constitutes an item of property, plant and equipment. At times, disaggregation of an item (as in componentisation) may be appropriate and at times aggregation of individually insignificant items such as mould, dies and tools may be appropriate, to apply the recognition criteria to the aggregate value.

All costs required to bring an asset into working condition should be recorded as part of the cost of the asset. Elements of such costs include:

- Its purchase price, including legal and brokerage fees, import duties and non‐refundable purchase taxes, after deducting trade discounts and rebates;

- Any directly attributable costs incurred to bring the asset to the location and operating condition as expected by management, including the costs of site preparation, delivery and handling, installation, set‐up and testing; and

- Estimated costs of dismantling and removing the item and restoring the site.

Government grants may be reduced to arrive at the carrying amount of the asset, in accordance with IAS 20, Accounting for Government Grants and Disclosure of Government Assistance.

These costs are capitalised and are not to be expensed in the period in which they are incurred, as they are deemed to add value to the asset and were necessary expenditures in acquiring the asset (see Chapter 21).

The costs required to bring acquired assets to the place where they are to be used includes such ancillary costs as testing and calibrating, where relevant. IAS 16 aims to distinguish between the costs of getting the asset to the state in which it is in a condition to be exploited (which are to be included in the asset's carrying amount) and costs associated with the start‐up operations, such as staff training, downtime between completion of the asset and the start of its exploitation, losses incurred through running at below normal capacity, etc., which are considered to be operating expenses. Any revenues that are earned from the asset during the installation process are netted off against the costs incurred in preparing the asset for use. As an example, the standard cites the sales of samples produced during this procedure.

However, on 14 May 2020 the IASB published amendments to IAS 16 which now prohibit deducting from the cost of an item of property, plant and equipment any proceeds from selling items produced and are effective for annual periods beginning on or after 1 January 2022.

IAS 16 distinguishes the situation described in the preceding paragraph from other situations where incidental operations unrelated to the asset may occur before or during the construction or development activities. For example, it notes that income may be earned through using a building site as a car parking lot until construction begins. Because incidental operations such as this are not necessary to bring the asset to the location and working condition necessary for it to be capable of operating in the manner intended by management, the income and related expenses of incidental operations are to be recognised in current earnings and included in their respective classifications of income and expense in profit or loss. These are not to be presented net, as in the earlier example of machine testing costs and sample sales revenues.

Administrative costs, as well as other types of overhead costs, are not normally allocated to fixed asset acquisitions, even though some costs, such as the salaries of the personnel who evaluate assets for proposed acquisitions, are incurred as part of the acquisition process. As a general principle, administrative costs are expensed in the period incurred, based on the perception that these costs are fixed and would not be avoided in the absence of asset acquisitions. On the other hand, truly incremental costs, such as a consulting fee or commission paid to an agent hired specifically to assist in the acquisition, may be treated as part of the initial amount to be recognised as the asset cost.

While interest costs incurred during the construction of certain qualifying assets must be added to the cost of the asset under IAS 23, Borrowing Costs (see Chapter 10), if an asset is purchased on deferred payment terms, the interest cost, whether made explicit or imputed, is not part of the cost of the asset. Accordingly, such costs must be expensed currently as interest charges. If the purchase price for the asset incorporates a deferred payment scheme, only the cash equivalent price should be capitalised as the initial carrying amount of the asset. If the cash equivalent price is not explicitly stated, the deferred payment amount should be reduced to present value by the application of an appropriate discount rate. This would normally be best approximated by the use of the entity's incremental borrowing cost for debt having a maturity similar to the deferred payment term, taking into account the risks relating to the asset under question that a financier would necessarily take into account.

Decommissioning cost included in initial measurement

The elements of cost to be incorporated in the initial recognition of an asset are to include the estimated costs of its eventual dismantlement (“decommissioning costs”). That is, the cost of the asset is “grossed up” for these estimated terminal costs, with the offsetting credit being posted to a liability account. It is important to stress that recognition of liability can only be effected when all the criteria outlined in IAS 37, Provisions, Contingent Liabilities and Contingent Assets, for the recognition of provisions are met. These stipulate that a provision is to be recognised only when:

- The reporting entity has a present obligation, whether legal or constructive, as a result of a past event;

- It is probable that an outflow of resources embodying economic benefits will be required to settle the obligation; and

- A reliable estimate can be made of the amount of the obligation.

For example, assume that it was necessary to secure a government licence to construct a particular asset, such as a power generating plant, and a condition of the licence is that at the end of the expected life of the property the owner would dismantle it, remove any debris and restore the land to its previous condition. These conditions would qualify as a present obligation resulting from a past event (the construction of the plant), which will probably result in a future outflow of resources. The cost of such future activities, while perhaps challenging to estimate due to the long‐time horizon involved and the possible intervening evolution of technology, can normally be accomplished with a requisite degree of accuracy. Per IAS 37, a best estimate is to be made of the future costs, which is then to be discounted to present value. This present value is to be recognised as an additional cost of acquiring the asset.

The cost of dismantlement and similar legal or constructive obligations do not extend to operating costs to be incurred in the future, since those would not qualify as “present obligations.” The precise mechanism for making these computations is addressed in Chapter 18.

If estimated costs of dismantlement, removal and restoration are included in the cost of the asset, the effect will be to allocate this cost over the life of the asset through the depreciation process. Each period the discounting of the provision should be “unwound,” such that interest cost is accreted each period. If this is done, at the expected date on which the expenditure is to be incurred the provision will be appropriately stated. The increase in the carrying amount of the provision should be reported as interest expense or a similar financing cost.

Changes in decommissioning costs

IFRIC 1 addresses the accounting treatment to be followed where a provision for reinstatement and dismantling costs has been created when an asset was acquired. The Interpretation requires that where estimates of future costs are revised, these should be applied prospectively only, and there is no adjustment to past years' depreciation. IFRIC 1 is addressed in Chapter 18 of this publication.

Initial recognition of self‐constructed assets

Essentially the same principles that have been established for recognition of the cost of purchased assets also apply to self‐constructed assets. Bearer plants, which from January 1, 2016, are included in the scope of IAS 16, are accounted for in the same manner as self‐constructed assets until the point where they are capable of being used in the manner intended by the entity.

All costs that must be incurred to complete the construction of the asset can be added to the amount to be recognised initially, subject only to the constraint that if these costs exceed the recoverable amount (as discussed fully later in this chapter), the excess must be expensed as an impairment loss. This rule is necessary to avoid the “gold‐plated hammer syndrome,” whereby a misguided or unfortunate asset construction project incurs excessive costs that then find their way into the statement of financial position, consequently overstating the entity's current net worth and distorting future periods' earnings. Of course, internal (intragroup) profits cannot be allocated to construction costs. The standard specifies that “abnormal amounts” of wasted material, labour or other resources may not be added to the cost of the asset.

Self‐constructed assets should include, in addition to the range of costs discussed earlier, the cost of borrowed funds used during the period of construction. Capitalisation of borrowing costs, as set forth by IAS 23, is discussed in Chapter 10.

Exchanges of assets

IAS 16 discusses the accounting to be applied to those situations in which assets are exchanged for other similar or dissimilar assets, with or without the additional consideration of monetary assets. This topic is addressed later in this chapter under the heading “Nonmonetary (Exchange) Transactions.”

Costs Incurred After Purchase or Self‐Construction

Costs that are incurred after the purchase or construction of the long‐lived asset, such as those for repairs, maintenance or betterments, may involve an adjustment to the carrying amount, or maybe expensed, depending on the precise facts and circumstances.

To qualify for capitalisation, the costs must meet the recognition criteria of an asset. For example, modifications to the asset made to extend its useful life (measured either in years or in units of potential production) or to increase its capacity (e.g., as measured by units of output per hour) would be capitalised. Similarly, if the expenditure results in an improved quality of output or permits a reduction in other cost inputs (e.g., would result in labour savings), it is a candidate for capitalisation. Where a modification involves changing part of the asset (e.g., substituting a stronger power source), the cost of the part that is removed should be derecognised (treated as a disposal).

For example, roofs of commercial buildings, linings of blast furnaces used for steel making and engines of commercial aircraft all need to be replaced or overhauled before the related buildings, furnaces or aircrafts themselves are replaced. If componentised depreciation was properly employed, the roofs, linings and engines were being depreciated over their respectively shorter useful lives, and when the replacements or overhauls are performed, on average, these will have been fully depreciated. To the extent that undepreciated costs of these components remain, they would have to be removed from the account (i.e., charged to expense in the period of replacement or overhaul) as the newly incurred replacement or overhaul costs are added to the asset accounts, to avoid having, for financial reporting purposes, “two roofs on one building.”

It can usually be assumed that ordinary maintenance and repair expenditures will occur on a rateable basis over the life of the asset and should be charged to expenses as incurred. Thus, if the purpose of the expenditure is either to maintain the productive capacity anticipated when the asset was acquired or constructed, or to restore it to that level, the costs are not subject to capitalisation.

A partial exception is encountered if an asset is acquired in a condition that necessitates that certain expenditures be incurred to put it into the appropriate state for its intended use. For example, a deteriorated building may be purchased with the intention that it be restored and then utilised as a factory or office facility. In such cases, costs that otherwise would be categorised as ordinary maintenance items might be subject to capitalisation. Once the restoration is completed, further expenditures of a similar type would be viewed as being ordinary repairs or maintenance, and thus expensed as incurred.

However, costs associated with required inspections (e.g., of aircraft) could be capitalised and depreciated. These costs would be amortised over the expected period of benefit (i.e., the estimated time to the next inspection). As with the cost of physical assets, removal of any undepreciated costs of previous inspections would be required. The capitalised inspection cost would have to be treated as a separate component of the asset.

Depreciation of Property, Plant and Equipment

The costs of property, plant and equipment are allocated through depreciation to the periods that will have benefited from the use of the asset. Whatever method of depreciation is chosen, it must result in the systematic and rational allocation of the depreciable amount of the asset (initial cost less residual value) over the asset's expected useful life. The determination of the useful life must take a number of factors into consideration. These factors include technological change, normal deterioration, actual physical use and legal or other limitations on the ability to use the property. The method of depreciation is based on whether the useful life is determined as a function of time or as a function of actual physical usage.

IAS 16 states that, although land normally has an unlimited useful life and is not to be depreciated, where the cost of the land includes estimated dismantlement or restoration costs, these are to be depreciated over the period of benefits obtained by incurring those costs. In some cases, the land itself may have a limited useful life, in which case it is to be depreciated in a manner that reflects the benefits to be derived from it.

IAS 16 requires that depreciation of an asset commences when it is available to use, i.e., when it is in the location and condition necessary for it to be capable of operating in the manner intended by management. Depreciation of an asset ceases at the earlier date of when the asset is derecognised and when the asset is classified as held for sale.

Since, under the historical cost convention, depreciation accounting is intended as a strategy for cost allocation, it does not reflect changes in the market value of the asset being depreciated (except in some cases where the impairment rules have been applied in that way—as discussed below). Thus, except for land, which has indefinite useful life, all tangible property, plant and equipment must be depreciated, even if (as sometimes occurs, particularly in periods of general price inflation) their nominal or real values increase. Furthermore, if the recorded amount of the asset is allocated over a period of time (as opposed to actual use), it should be the expected period of usefulness to the entity, not the physical or economic life of the asset itself that governs. Thus, concerns such as technological obsolescence, as well as normal wear and tear, must be addressed in the initial determination of the period over which to allocate the asset cost. The reporting entity's strategy for repairs and maintenance will also affect this computation, since the same physical asset might have a longer or shorter useful life in the hands of differing owners, depending on the care with which it is intended to be maintained.

Similarly, the same asset may have a longer or shorter useful life, depending on its intended use. A particular building, for example, may have a 50‐year expected life as a facility for storing goods or for use in light manufacturing, but as a showroom would have a shorter period of usefulness, due to the anticipated disinclination of customers to shop at entities housed in older premises. Again, it is not physical life, but useful life, that should govern.

Compound assets, such as buildings containing such disparate components as heating plant, roofs and other structural elements, are most commonly recorded in several separate accounts to facilitate the process of depreciating the different elements over varying periods. Thus, a heating plant may have an expected useful life of 20 years, the roof a life of 15 years and the basic structure itself a life of 40 years. Maintaining separate ledger accounts eases the calculation of periodic depreciation in such situations, although for financial reporting purposes a greater degree of aggregation is usual.

IAS 16 requires a component approach for depreciation, where, as described above, each significant component of a composite asset with different useful lives or different patterns of depreciation is accounted for separately for depreciation and accounting for subsequent expenditure (including replacement and renewal). Thus, rather than recording a newly acquired or existing office building as a single asset, it is recorded as a building shell, a heating plant, a roof and perhaps other discrete mechanical components, subject to a materiality threshold. Allocation of cost over useful lives, instead of being based on a weighted‐average of the varying components' lives, is based on separate estimated lives for each component.

The depreciation is usually charged to the statement of profit and loss. However, there could be exceptions wherein such depreciation costs are included in the cost of another asset, if the depreciation was incurred in the construction of another asset in which the future economic benefit of such use is embodied. In such cases, the depreciation could be added to the cost and carrying value of such property, plant and equipment. It is also provided under IAS 2, Inventories, and IAS 38, Intangible Assets, for depreciation to be added to the cost of the inventory manufactured or cost of the intangible, if it meets the requirements of these standards.

IAS 16 states that the depreciation method should reflect the pattern in which the asset's future economic benefits are expected to be consumed by the entity, and that appropriateness of the method should be reviewed at least annually in case there has been a change in the expected pattern. Beyond that, the standard leaves the choice of method to the entity, even though it does cite straight‐line, diminishing balance and units of production as possible depreciation methods.

A depreciation method that is based on revenues that are generated by activities including the use of an asset are not appropriate, as revenue generally reflects factors other than the consumption of the economic benefits inherent within an asset.

Depreciation methods based on time

- Straight‐line—Depreciation expense is incurred evenly over the life of the asset. The periodic charge for depreciation is given as:

- Accelerated methods—Depreciation expense is higher in the early years of the asset's useful life and lower in the later years. IAS 16 only mentions one accelerated method, the diminishing balance method, but other methods have been employed in various national GAAP under earlier or contemporary accounting standards.

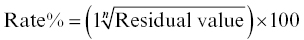

- Diminishing balance—the depreciation rate is applied to the net carrying amount of the asset, resulting in a diminishing annual charge. There are various ways to compute the percentage to be applied. The formula below provides a mathematically correct allocation over useful life:

where n is the expected useful life in years. However, companies generally use approximations or conventions influenced by tax practice, such as a multiple of the straight‐line rate times the net carrying amount at the beginning of the year:

- Double‐declining balance depreciation (if salvage value is to be recognised, stop when carrying amount = estimated salvage value):

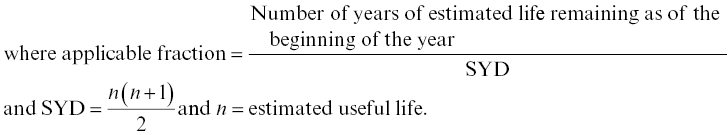

Another method to accomplish a diminishing charge for depreciation is the sum‐of‐the‐years' digits method, which is commonly employed in the US and certain other venues.

- Sum‐of‐the years' digits (SYD) depreciation = (Cost less salvage value) × Applicable fraction

- Diminishing balance—the depreciation rate is applied to the net carrying amount of the asset, resulting in a diminishing annual charge. There are various ways to compute the percentage to be applied. The formula below provides a mathematically correct allocation over useful life:

In practice, unless there are tax reasons to employ accelerated methods, large companies tend to use straight‐line depreciation. This has the merit that it is simple to apply, and where a company has a large pool of similar assets, some of which are replaced each year, the aggregate annual depreciation charge is likely to be the same, irrespective of the method chosen (consider a trucking company that has 10 trucks, each costing €200,000, one of which is replaced each year: the aggregate annual depreciation charge will be €200,000 under any mathematically accurate depreciation method).

Partial‐year depreciation

Although IAS 16 is silent on the matter, when an asset is either acquired or disposed of during the year, the full‐year depreciation calculation should be prorated between the accounting periods involved. This is necessary to achieve proper matching. However, if individual assets in a relatively homogeneous group are regularly acquired and disposed of, one of several conventions can be adopted, as follows:

- Record a full year's depreciation in the year of acquisition and none in the year of disposal.

- Record one‐half year's depreciation in the year of acquisition and one‐half year's depreciation in the year of disposal.

Depreciation method based on actual physical use—units of production method

Depreciation may also be based on the number of units produced by the asset in a given year. IAS 16 identifies this as the units of production method, but it is also known as the sum of the units approach. It is best suited to those assets, such as machinery, that have an expected life that is most rationally defined in terms of productive output; in periods of reduced production (such as economic recession) the machinery is used less, thus extending the number of years it is likely to remain in service. This method has the merit that the annual depreciation expense fluctuates with the contribution made by the asset each year. Furthermore, if the depreciation finds its way into the cost of finished goods, the unit cost in periods of reduced production would be exaggerated and could even exceed net realisable value unless the units of production approach to depreciation was taken.

Units of production depreciation = Depreciation rate × Number of units produced during the period

Residual value

Most depreciation methods discussed above require that depreciation is applied not to the full cost of the asset, but to the “depreciable amount”; that is, the historical cost or amount substituted therefor (i.e., fair value) less the estimated residual value of the asset. As IAS 16 points out, residual value is often not material and in practice is frequently ignored, but it may impact upon some assets, particularly when the entity disposes of them early in their life (e.g., rental vehicles) or where the residual value is so high as to negate any requirement for depreciation (some hotel companies, for example, claim that they have to maintain their premises to such a high standard that their residual value under historical cost is higher than the original cost of the asset).

Under IAS 16, residual value is defined as the estimated amount that an entity would currently obtain from disposal of the asset, after deducting the estimated costs of disposal, if the asset were already of the age and in the condition expected at the end of its useful life. The residual value is, like all aspects of the depreciation method, subject to at least annual review.

If the revaluation method of measuring property, plant and equipment is chosen, residual value must be assessed anew at the date of each revaluation of the asset. This is accomplished by using data on realisable values for similar assets, ending their respective useful lives at the time of the revaluation, after having been used for purposes similar to the asset being valued. Again, no consideration can be paid to anticipated inflation, and expected future values are not to be discounted to present values to give recognition to the time value of money.

Useful lives

Useful life is affected by such things as the entity's practices regarding repairs and maintenance of its assets, as well as the pace of technological change and the market demand for goods produced and sold by the entity using the assets as productive inputs. Useful life is also affected by the usage pattern of the asset, such as the number of shifts the asset is put to use in the operations and at times the useful life determined considering this may require a relook when, say, originally the useful life was determined based on single shift operation and now the company's operations have become double or triple shift and is likely to continue at such pace in the future. If it is determined, when reviewing the depreciation method, that the estimated life is greater or less than previously believed, the change is treated as a change in accounting estimate, not as a correction of an accounting error. Accordingly, no restatement is to be made to previously reported depreciation; rather, the change is accounted for strictly on a prospective basis, being reflected in the period of change and subsequent periods.

Tax methods

The methods of computing depreciation discussed in the foregoing sections relate only to financial reporting under IFRS. Tax laws in the different nations of the world vary widely in terms of the acceptability of depreciation methods, and it is not possible to address all these. However, to the extent that depreciation allowable for income tax reporting purposes differs from that required or permitted for financial statement purposes, deferred income taxes would have to be computed. Deferred tax is discussed in Chapter 26.

LEASEHOLD IMPROVEMENTS

Leasehold improvements are improvements to property not owned by the party making these investments. For example, a lessee of office space may invest its funds to install partitions or to combine several suites by removing certain interior walls. Due to the nature of these physical changes to the property (done with the lessor's permission, of course), the lessee cannot remove or undo these changes and must abandon them upon termination of the lease, if the lessee does not remain in the facility.

A frequently encountered issue concerning leasehold improvements relates to determination of the period over which they are to be amortised. Normally, the cost of long‐lived assets is charged to expense over the estimated useful lives of the assets. However, the right to use a leasehold improvement expires when the related lease expires, irrespective of whether the improvement has any remaining useful life. Thus, the appropriate useful life for a leasehold improvement is the lesser of the useful life of the improvement or the term of the underlying lease.

Some leases contain a fixed, non‐cancellable term and additional renewal options. When considering the term of the lease to depreciate leasehold improvements, normally only the initial fixed non‐cancellable term is included. There are, however, exceptions to this general rule. If a renewal option is a bargain renewal option, which means that it is probable at the inception of the lease that it will be exercised, the option period should be included in the lease term for purposes of determining the amortisable life of the leasehold improvements. Additionally, under the definition of the lease term there are other situations where it is probable that an option to renew for an additional period would be exercised. These situations include periods for which failure to renew the lease imposes a penalty on the lessee in such amount that a renewal appears, at the inception of the lease, to be reasonably assured. Other situations of this kind arise when an otherwise excludable renewal period precedes a provision for a bargain purchase of the leased asset or when, during periods covered by ordinary renewal options, the lessee has guaranteed the lessor's debt on the leased property.

Revaluation of Property, Plant and Equipment

IAS 16 provides for two acceptable alternative approaches to accounting for long‐lived tangible assets. The first of these is the historical cost method, under which acquisition or construction cost is used for initial recognition, subject to depreciation over the expected useful life and to possible write‐down in the event of a permanent impairment in value. In many jurisdictions this is the only method allowed by statute, but some jurisdictions, particularly those with significant rates of inflation, do permit either full or selective revaluation and IAS 16 acknowledges this by also allowing what it calls the “revaluation model.” Under the revaluation model, after initial recognition as an asset, an item of property, plant and equipment whose fair value can be measured reliably should be carried at a revalued amount, being its fair value at the date of the revaluation less any subsequent accumulated depreciation and subsequent accumulated impairment losses.

The logic of recognising revaluations relates to both the statement of financial position and the measure of periodic performance provided by the statement of profit or loss and other comprehensive income. Due to the effects of inflation (which even if quite moderate when measured on an annual basis can compound dramatically during the lengthy period over which property, plant and equipment remain in use) the statement of financial position can become virtually meaningless agglomeration of dissimilar costs.

Furthermore, if the depreciation charge to income is determined by reference to historical costs of assets acquired in much earlier periods, profits will be overstated, and will not reflect the cost of maintaining the entity's asset base. Under these circumstances, a nominally profitable entity might find that it has self‐liquidated and is unable to continue in existence, at least not with the same level of productive capacity, without new debt or equity infusions. IAS 29, Financial Reporting in Hyperinflationary Economies, addresses adjustments to depreciation under conditions of hyperinflation.

Under the revaluation model the frequency of revaluations depends upon the changes in fair values of the items being revalued and, consequently, when the fair value of a revalued asset differs materially from its carrying amount, a further revaluation is required.

Fair value

As the basis for the revaluation method, the standard stipulates that it is fair value (defined as the price that would be received to sell an asset or paid to transfer a liability in an orderly transaction between market participants at the measurement date) that is to be used in any such revaluations. Furthermore, the standard requires that, once an entity undertakes revaluations, they must continue to be made with sufficient regularity that the carrying amounts in any subsequent statements of financial position are not materially at variance with the then‐current fair values. In other words, if the reporting entity adopts the revaluation method, it cannot report obsolete fair values in the statements of financial position that contain previous years' comparative data, since that would not only obviate the purpose of the allowed treatment but would actually make it impossible for the user to meaningfully interpret the financial statements. Accordingly, the IASB recommends that a class of assets should be revalued on a rolling basis provided revaluation of the class of assets is completed within a short period and provided the revaluations are kept up to date.

Fair value is usually determined by appraisers, using market‐based evidence. Market values can also be used for machinery and equipment, but since such items often do not have readily determinable market values, particularly if intended for specialised applications, they may instead be valued at depreciated replacement cost. Fair value is determined in terms of IFRS 13, Fair Value Measurements. The standard is presented in further detail in Chapter 25.

A recent amendment to IAS 16 has clarified that the gross value is restated (either by reference to market data or proportionally to the change in carrying amount) and that accumulated depreciation is the difference between the new gross amount and the new carrying amount.

An alternative accounting procedure is also permitted by the standard, under which the accumulated depreciation at the date of the revaluation is written off against the gross carrying amount of the asset. In the foregoing example, this would mean that the €12,000 of accumulated depreciation at January 1, 202X+3, immediately prior to the revaluation, would be credited to the gross asset amount, €40,000, thereby reducing it to €28,000. Then the asset account would be adjusted to reflect the valuation of €35,000 by increasing the asset account by €7,000 (= €35,000 – €28,000), with the offset to other comprehensive income (and accumulated in the revaluation surplus in shareholders' equity). In terms of total assets reported in the statement of financial position, this has the same effect as the first method.

Revaluation applied to all assets in the class

IAS 16 requires that if any assets are revalued, all other assets in those groupings or categories must also be revalued. This is necessary to prevent the presentation in a statement of financial position that contains an unintelligible and possibly misleading mix of historical costs and fair values, and to preclude selective revaluation designed to maximise reported net assets. Coupled with the requirement that revaluations take place with sufficient frequency to approximate fair values at the end of each reporting period, this preserves the integrity of the financial reporting process. In fact, given that a statement of financial position prepared under the historical cost method will contain non‐comparable values for similar assets (due to assets having been acquired at varying times, at differing price levels), the revaluation approach has the possibility of providing more consistent financial reporting. Offsetting this potential improvement, at least somewhat, is the greater subjectivity inherent in the use of fair values, providing an example of the conceptual framework's trade‐off between relevance and reliability.

Revaluation adjustments

In general, revaluation adjustments increasing an asset's carrying amount are recognised in other comprehensive income and accumulated in equity as revaluation surplus. However, the increase should be recognised in profit or loss to the extent that it reverses a revaluation decrease (impairment) of the same asset previously recognised in profit or loss. If a revalued asset is subsequently found to be impaired, the impairment loss is recognised in other comprehensive income only to the extent that the impairment loss does not exceed the amount in the revaluation surplus for the same asset. Such an impairment loss on a revalued asset is first offset against the revaluation surplus for that asset, and only when that has been exhausted is it recognised in profit or loss.

Revaluation adjustments decreasing an asset's carrying amount, in general, are recognised in profit or loss. However, the decrease should be recognised in other comprehensive income to the extent of any credit balance existing in the revaluation surplus in respect of that asset. The decrease recognised in other comprehensive income reduces the amount accumulated in equity in the revaluation surplus account.

Under the provisions of IAS 16, the amount credited to revaluation surplus can either be transferred directly to retained earnings (but not through profit or loss!) as the asset is being depreciated, or it can be held in the revaluation surplus account until such time as the asset is disposed of or retired from service. Any transfer to retained earnings is limited to the amount equal to the difference between depreciation based on the revalued carrying amount of the asset and depreciation based on the asset's original cost. In addition, revaluation surplus may be transferred directly to retained earnings when the asset is derecognised. This would involve transferring the whole of the surplus when the asset is retired or disposed of.

Initial revaluation

Under the revaluation model in IAS 16, at the date of initial revaluation of an item of property, plant and equipment, revaluation adjustments are accounted for as follows:

- Increases in an asset's carrying amount are credited to other comprehensive income (gain on revaluation); and

- Decreases in an asset's carrying amount are charged to profit or loss as this is deemed to be an impairment recognised on the related asset.

Subsequent revaluation

As per IAS 16, in subsequent periods, revaluation adjustments are accounted for as follows:

- Increases in an asset's carrying amount (upward revaluation) should be recognised as income in profit or loss to the extent of the amount of any previous impairment loss recognised, and any excess should be credited to equity through other comprehensive income;

- Decreases in an asset's carrying amount (downward revaluation) should be charged to other comprehensive income to the extent of any previous revaluation surplus, and any excess should be debited to profit or loss as an impairment loss.

Methods of adjusting accumulated depreciation at the date of revaluation

When an item of property, plant and equipment is revalued, any accumulated depreciation at the date of the revaluation is treated in one of the following ways:

- Restate accumulated depreciation to reflect the difference between the change in the gross carrying amount of the asset and the revalued amount (so that the carrying amount of the asset after revaluation equals its revalued amount); or

- Eliminate the accumulated depreciation against the gross carrying amount of the asset.

This method is often used for buildings. In terms of total assets reported in the statement of financial position, option 2 has the same effect as option 1.

However, many users of financial statements, including credit grantors and prospective investors, pay heed to the ratio of net property and equipment as a fraction of the related gross amounts. This is done to assess the relative age of the entity's productive assets and, indirectly, to estimate the timing and amounts of cash needed for asset replacements. There is a significant diminution of information under the second method. Accordingly, the first approach described above, preserving the relationship between gross and net asset amounts after the revaluation, is recommended as the preferable alternative if the goal is meaningful financial reporting.

Deferred tax effects of revaluations

Chapter 26 describes how the tax effects of temporary differences must be provided for. Where assets are depreciated over longer lives for financial reporting purposes than for tax reporting purposes, a deferred tax liability will be created in the early years and then drawn down in later years. Generally speaking, the deferred tax provided will be measured by the expected future tax rate applied to the temporary difference at the time it reverses; unless future tax rate changes have already been enacted, the current rate structure is used as an unbiased estimator of those future effects.

In the case of revaluation of assets, it may be that taxing authorities will not permit the higher revalued amounts to be depreciated for purposes of computing tax liabilities. Instead, only the actual cost incurred can be used to offset tax obligations. On the other hand, since revaluations reflect a holding gain, this gain would be taxable if realised. Accordingly, a deferred tax liability is still required to be recognised, even though it does not relate to temporary differences arising from periodic depreciation charges.

SIC 21 confirmed that measurement of the deferred tax effects relating to the revaluation of non‐depreciable assets must be made concerning the tax consequences that would follow from recovery of the carrying amount of that asset through an eventual sale. This is necessary because the asset will not be depreciated, and hence no part of its carrying amount is considered to be recovered through use. As a practical matter this means that if there are differential capital gain and ordinary income tax rates, deferred taxes will be computed with reference to the former. This guidance of SIC 21 has now been incorporated into IAS 12 as part of a December 2010 amendment, which became effective for annual periods commencing on or after January 1, 2012. SIC 21 was consequently withdrawn with effect from that date.

DERECOGNITION

An entity should derecognise an item of property, plant and equipment (1) on disposal, or (2) when no future economic benefits are expected from its use or disposal. In such cases an asset is removed from the statement of financial position. In the case of property, plant and equipment, both the asset and the related contra asset, accumulated depreciation, should be eliminated. The difference between the net carrying amount and any proceeds received will be recognised immediately as a gain or loss arising on derecognition, through the statement of profit and loss, except where IFRS 16 requires otherwise on a sale and leaseback transaction.

If the revaluation method of accounting has been employed, and the asset and the related accumulated depreciation account have been adjusted upward, if the asset is subsequently disposed of before it has been fully depreciated, the gain or loss computed will be identical to what would have been determined had the historical cost method of accounting been used. The reason is that, at any point in time, the net amount of the revaluation (i.e., the step‐up in the asset less the unamortised balance in the step‐up in accumulated depreciation) will be offset exactly by the remaining balance in the revaluation surplus account. Elimination of the asset, contra asset, and revaluation surplus accounts will balance precisely, and there will be no gain or loss on this aspect of the disposition transaction. The gain or loss will be determined exclusively by the discrepancy between the net carrying amount, based on historical cost, and the proceeds from the disposition. Thus, the accounting outcome is identical under cost and revaluation methods.

In the case of assets (or disposal groups) identified as “held for sale,” depreciation will cease once such determination is effected and the amount will be derecognised from Property, Plant and Equipment and accounted separately under “Assets Held for Sale.”

In case of an entity that in its normal course routinely sells items of property, plant and equipment that it has held for rental to others once they are ceased from being rented and is considered as held for sale, such items could be transferred to inventories at their carrying value and be considered as inventory to be thereafter, on sale, recognised as revenue in accordance with IFRS 15, Revenue from Customers.

DISCLOSURES

The disclosures required under IAS 16 for property, plant and equipment, and under IAS 38 for intangibles, are similar. Furthermore, IAS 36 requires extensive disclosures when assets are impaired or when formerly recognised impairments are being reversed. The requirements that pertain to property, plant and equipment are as follows:

For each class of tangible asset, disclosure is required of:

- The measurement basis used (cost or revaluation approaches).

- The depreciation method(s) used.

- Useful lives or depreciation rates used.

- The gross carrying amounts and accumulated depreciation at the beginning and the end of the period.

- A reconciliation of the carrying amount from the beginning to the end of the period, showing additions, disposals and/or assets included in disposal groups or classified as held for sale, acquisitions by means of business combinations, increases or decreases resulting from revaluations, reductions to recognised impairments, depreciation, the net effect of translation of foreign entities' financial statements and any other material items.

In addition, the financial statements should also disclose the following facts:

- Any restrictions on titles and any assets pledged as security for debt.

- The accounting policy regarding restoration costs for items of property, plant and equipment.

- The expenditures made for property, plant and equipment, including any construction in progress.

- The amount of outstanding commitments for property, plant and equipment acquisitions.

- The amount received from any third parties as compensation for any impaired, lost or given‐up asset. This is only applicable if the amount received was not separately disclosed in the statement of comprehensive income.

Non‐Monetary (Exchange) Transactions

Businesses sometimes engage in non‐monetary exchange transactions, where tangible or intangible assets are exchanged for other assets, without a cash transaction or with only a small amount of cash “settle‐up.” These exchanges can involve productive assets such as machinery and equipment, which are not held for sale under normal circumstances, or inventory items, which are intended for sale to customers.

IAS 16 guides the accounting for non‐monetary exchanges of tangible assets. It requires that the cost of an item of property, plant and equipment acquired in exchange for a similar asset is to be measured at fair value, provided that the transaction has commercial substance. The concept of a purely “book value” exchange, formerly employed, is now prohibited under most circumstances.

Commercial substance is defined as the event or transaction causing the cash flows of the entity to change. That is, if the expected cash flows after the exchange differ from what would have been expected without this occurring, the exchange has commercial substance and is to be accounted for at fair value. In assessing whether this has occurred, the entity has to consider if the amount, timing and uncertainty of the cash flows from the new asset are different from the one given up, or if the entity‐specific portion of the company's operations will be different. If either of these is significant, then the transaction has commercial substance.

If the transaction does not have commercial substance, or the fair value of neither the asset received nor the asset given up can be measured reliably, then the asset acquired is valued at the carrying amount of the asset given up. Such situations are expected to be rare.

If there is a settle‐up paid or received in cash or a cash equivalent, this is often referred to as boot; that term will be used in the following example.

Non‐reciprocal transfers

In a non‐reciprocal transfer, one party gives or receives property without the other party doing the opposite. Often these involve an entity and the owners of the entity. Examples of non‐reciprocal transfers with owners include dividends paid‐in‐kind, non‐monetary assets exchanged for common stock, split‐ups and spin‐offs. An example of a non‐reciprocal transaction with parties other than the owners is a donation of property either by or to the entity.

The accounting for most non‐reciprocal transfers should be based on the fair market value of the asset given (or received, if the fair value of the non‐monetary asset is both objectively measurable and would be recognisable under IFRS). The same principle also applies to distributions of non‐cash assets (e.g., items of property, plant and equipment, businesses as defined in IFRS 3, ownership interest in another entity, or disposal groups as defined in IFRS 5); and also, to distributions that give owners a choice of receiving either non‐cash assets or a cash alternative. IFRIC 17 was issued in January 2009 to address the accounting that should be followed in such situations and provides that the assets involved must be measured at their fair value and any gains or losses taken to profit or loss. The Interpretation also guides the measurement of the dividend payable in that the dividend payable is measured at the fair value of the assets to be distributed. If the entity gives its owners a choice of receiving either a non‐cash asset or a cash alternative, the entity should estimate the dividend payable by considering both the fair value of each alternative and the associated probability of owners selecting each alternative. At the end of each reporting period and the date of settlement, the entity is required to review and adjust the carrying amount of the dividend payable, with any changes in the carrying amount of the dividend payable recognised in equity as adjustments to the amount of the distribution.

This approach differs from the previous approach, which permitted the recording of transactions that resulted in the distribution of non‐monetary assets to owners of an entity in a spin‐off or other form of reorganisation or liquidation being accounted for based on their recorded amount.

Transfers of Assets from Customers

IFRIC 18, Transfers of Assets from Customers, has been replaced by IFRS 15. The IFRS does not refer specifically to the phrase “transfer of assets from clients”; however, included in the measurement provisions, specifically the paragraphs relating to determination of the transaction price, there is section on how to treat non‐cash considerations received.

IFRS 15 requires that when a customer contributes goods or services to facilitate the entity fulfilling its contractual obligations, the entity must consider whether it assumes control of these goods or services. If the entity does gain control of these goods or services, the standard then says that these goods or services can be accounted for as non‐cash consideration received. The value of this consideration, the transaction price, is then measured at the fair value of the non‐cash consideration (i.e., goods or services provided by the customer). Based on the simple double entry accounting system one must then infer that the resulting asset should be measured at the fair value of the non‐cash consideration.

One will need to be sure that the items received meet the definition of an item of Property, Plant and Equipment (PPE) before they recognise the item as PPE. In situations where the fair value of the non‐cash consideration is not estimated reasonably, the measurement of consideration in determining revenue recognition related to the receipt of the non‐cash consideration, and whether or not there is a need to raise deferred revenue, one will need to take into account the revenue recognition principles of IFRS 15; these are dealt with in Chapter 20 of this book.

EXAMPLES OF FINANCIAL STATEMENT DISCLOSURES

| Exemplum Reporting PLC Financial Statements For the Year Ended December 31, 202X | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Summary of significant accounting policies | |||||

| 2.5 Property, plant and equipment | |||||

| All property, plant and equipment assets are stated at cost less accumulated depreciation. | |||||

Depreciation of property, plant and equipment is provided to write off the cost, less residual value, on a straight‐line basis over the estimated useful life

| |||||

| Residual values, remaining useful lives and depreciation methods are reviewed annually and adjusted if appropriate. | |||||

| Gains or losses on disposal are included in profit or loss | |||||

| 2.16 Discontinued operations and non‐current assets held for sale | |||||

| The results of discontinued operations are to be presented separately in the statement of comprehensive income. | |||||

| Non‐current assets (or disposal group) classified as held for sale are measured at the lower of carrying amount and fair value less costs to sell. | |||||

| Non‐current assets (or disposal group) are classified as held for sale if their carrying amount will be recovered through a sale transaction rather than through continuing use. | |||||

| This is the case when the asset (or disposal group) is available for immediate sale in its present condition subject only to terms that are usual and customary for sales of such assets (or disposal groups) and the sale is considered to be highly probable. | |||||

| A sale is considered to be highly probable if the appropriate level of management is committed to a plan to sell the asset (or disposal group), and an active programme to locate a buyer and complete the plan has been initiated. Further, the asset (or disposal group) has been actively marketed for sale at a price that is reasonable in relation to its current fair value. Also, the sale is expected to qualify for recognition as a completed sale within one year from the date that it is classified as held for sale. | |||||

| 3. Accounting estimates and judgements | |||||

| The estimates and judgements that have a significant risk of causing a material adjustment to the carrying amounts of assets and liabilities within the next financial year are as follows: | |||||

| 3.1 Key sources of estimation uncertainty | |||||

| Useful lives of items of property, plant and equipment | |||||

| The group reviews the estimated useful lives of property, plant and equipment at the end of each reporting period. During the current year, the directors determined that the useful lives of certain items of equipment should be shortened, due to developments in technology. | |||||

| The financial effect of this reassessment is to increase the consolidated depreciation expense in the current year and for the next three years, by the following amounts: | |||||

| 202X €X | |||||

| 202X+1 €X | |||||

| 202X+2 €X | |||||

| 202X+3 €X | |||||

| 15. Property, Plant and Equipment | |||||

| GROUP | LAND AND BUILDINGS | PLANT AND MACHINERY | FURNITURE AND FITTINGS | TOTAL | |

| COST | € | € | € | € | |

| Opening cost at January 1, 202X‐1 | X | X | X | X | |

| Additions | X | X | X | X | |

| Exchange differences | X | X | X | X | |

| Classified as held for sale | |||||

| Disposals | X | X | X | X | |

| Acquired through business combination | X | X | X | X | |

| Opening cost at January 1, 202X | X | X | X | X | |

| Additions | X | X | X | X | |

| Exchange differences | X | X | X | X | |

| Classified as held for sale | |||||

| Disposals | X | X | X | X | |

| Acquired through business combination | X | X | X | X | |

| Closing cost at December 31, 202X | X | X | X | X | |

| Accumulated depreciation/impairment | |||||

| Opening balance at January 1, 202X‐1 | X | X | X | X | |

| Depreciation | X | X | X | X | |

| Disposals | X | X | X | X | |

| Exchange differences | X | X | X | X | |

| Impairment loss | X | X | X | X | |

| Opening balance at January 1, 202X | X | X | X | X | |

| Depreciation | X | X | X | X | |

| Disposals | X | X | X | X | |

| Exchange differences | X | X | X | X | |

| Impairment loss | X | X | X | X | |

| Impairment reversal | X | X | X | X | |

| Closing balance at December 31, 202X | X | X | X | X | |

| Opening carrying value at January 1, 202X‐1 | X | X | X | X | |

| Opening carrying value at January 1, 202X | X | X | X | X | |

| Closing carrying value at December 31, 202X | X | X | X | X | |

| Plant and machinery includes the following amounts where the group is a lessee under a finance lease: | |||||

| 202X € | 202X‐1 € | ||||

| Cost—capitalised finance leases | X | X | |||

| Accumulated depreciation | X | X | |||

| Net book value | X | X | |||

In determining the valuations for land and buildings, the valuer refers to current market conditions including recent sales transactions of similar properties—assuming the highest and best use of the properties.

For plant and machinery, current replacement cost adjusted for the depreciation factor of the existing assets is used. There has been no change in the valuation technique used during the year compared to prior periods.

The fair valuation of property, plant and equipment is considered to represent a level 3 valuation based on significant non‐observable inputs being the location and condition of the assets and replacement costs for plant and machinery.

Management does not expect there to be a material sensitivity to the fair values arising from the non‐observable inputs.

There were no transfers between level 1, 2 and 3 fair values during the year.

The table above presents the changes in the carrying value of the property, plant and equipment arising from these fair valuation assessments.

US GAAP COMPARISON

US GAAP and IFRS are very similar with regard to property, plant and equipment. Generally, expenditures that qualify for capitalisation under IFRS are also eligible under US GAAP as recorded in FASB ASC 360 Property, Plant and Equipment.

Initial measurement can differ for internally constructed assets. US GAAP permits only eligible interest to be capitalised, whereas IFRS includes other borrowing costs. There are also some differences regarding what borrowings are included to compute a capitalisation rate. For costs connected to a specific asset, borrowing costs equal the weighted‐average of accumulated expenditures times the borrowing rate.

Component accounting is not prescribed under US GAAP, but neither is it prohibited, and it is not common. This disparity can result in a different “mix” of depreciation and maintenance expense on the income statement. Only major upgrades to PPE are capitalised under US GAAP, whereas the replacement of a component under IFRS is characterised as accelerated depreciation and additional capital expenditures. Consequently, the classification of expenditures on the statement of cash flows can differ.

Most oil and gas companies use US GAAP for exploration assets since there is no substantial IFRS for the oil and gas industry. IFRS 6 permits entities to disregard the hierarchy of application prescribed in IAS 8 and use another standard (usually US GAAP) immediately.

The accounting for asset retirement obligations assets is largely the same but the difference in the discount rate used to measure the fair value of the liability creates an inherent difference in the carrying cost. US GAAP uses a credit‐adjusted, risk‐free rate adjusted for the entity's credit risk to discount the obligation. IFRS uses the time value of money rate adjusted for specific risks of the liability. Also, assets and obligations are not adjusted for period‐to‐period changes in the discount. The discount rate applied to each upward revision of an accrual, termed “layers” in US GAAP, remains with that layer through increases and decreases.

US GAAP requires a two‐step method approach to impairment measuring. If the asset fails the first step (future undiscounted cash flows exceed the carrying amount), the second step requires an impairment loss calculated as the excess of carrying amount over fair value.

US GAAP does not permit revaluations of property, plant and equipment or mineral resources.