CHAPTER 5

Writing for Video

Action is character.

—F. Scott Fitzgerald

Key Terms

![]() Camera script: Adds full details of the production treatment to the left side of the “rehearsal script” and usually also includes the shot numbers, cameras used, positions of camera, basic shot details, camera moves, and switcher instructions (if used).

Camera script: Adds full details of the production treatment to the left side of the “rehearsal script” and usually also includes the shot numbers, cameras used, positions of camera, basic shot details, camera moves, and switcher instructions (if used).

![]() Cue card: The talent may read questions or specific points from a cue card that is positioned near the camera. Generally it is held next to the camera lens.

Cue card: The talent may read questions or specific points from a cue card that is positioned near the camera. Generally it is held next to the camera lens.

![]() Format (running order): The show format lists the items or program segments in a show in the order they are to be shot. The format generally shows the duration of each segment and possibly the camera assignments.

Format (running order): The show format lists the items or program segments in a show in the order they are to be shot. The format generally shows the duration of each segment and possibly the camera assignments.

![]() Full script: A fully scripted program includes detailed information on all aspects of the production. This includes the precise words that the talent/ actors are to use in the production.

Full script: A fully scripted program includes detailed information on all aspects of the production. This includes the precise words that the talent/ actors are to use in the production.

![]() Outline script: Usually provides the prepared dialog for the opening and closing and then lists the order of topics that should be covered. The talent will use the list as they improvise throughout the production.

Outline script: Usually provides the prepared dialog for the opening and closing and then lists the order of topics that should be covered. The talent will use the list as they improvise throughout the production.

![]() Rehearsal script: Usually includes the cast/character list, production team details, rehearsal arrangements, and so forth. There is generally a synopsis of the plot or story line, location, time of day, stage/location instructions, action, dialog, effects cues, and audio instructions.

Rehearsal script: Usually includes the cast/character list, production team details, rehearsal arrangements, and so forth. There is generally a synopsis of the plot or story line, location, time of day, stage/location instructions, action, dialog, effects cues, and audio instructions.

![]() Scene: Each scene covers a complete continuous action sequence.

Scene: Each scene covers a complete continuous action sequence.

5.1 THE SCRIPT’S PURPOSE

If you are working entirely by yourself on a simple production, you might get away with a few notes on the back of an envelope. But planning is an essential part of a serious production, and the script forms the basis for that plan.

![]() Help the director to clarify ideas and to develop a project that works

Help the director to clarify ideas and to develop a project that works

![]() Help to coordinate the production team (Figure 5.1)

Help to coordinate the production team (Figure 5.1)

![]() Help the director to assess the resources needed for the production

Help the director to assess the resources needed for the production

FIGURE 5.1

Director, on the set of a sitcom, discussing the script with the writers. Scripts help coordinate the production team.

Although some professional crews on location (at a news event, for instance) may appear to be shooting entirely spontaneously, they are invariably working through a process or pattern that has proved successful in the past.

For certain types of productions, such as a drama, the script generally begins the production process. The director reads the draft script, which usually contains general information on characters, locations, stage directions, and dialog. He or she then envisions the scenes and assesses possible treatment. The director must also anticipate the script’s possibilities and potential problems. At this stage, changes may be made to improve the script or make it more practical. Next, the director prepares a camera treatment.

Another method of scripting begins with an outline. Here you decide on the various topics you want to cover and the amount of time you can allot to each topic. A script is then developed based on this outline, and a decision is made concerning the camera treatment for each segment.

When preparing a documentary, an extended outline becomes a shooting script, possibly showing the types of shots that will be required. It may also include rough questions for on-location interviews. All other commentary is usually written later, together with effects and music, to fit the edited program.

5.2 IS A SCRIPT NEEDED?

The type of script used will largely depend on the kind of program you are making. In some production situations, particularly where talent improvise as they speak or perform, the “script” simply lists details of the production group, facilities needed, and scheduling requirements, and it shows basic camera positions, among other fine points.

An outline script usually includes any prepared dialog such as the show opening and closing. If people are going to improvise, the script may simply list the order of topics to be covered. During the show, the list may be included on a card that the talent holds, on a cue card positioned near the camera, or on a teleprompter as a reminder for the host. If the show is complicated with multiple guests or events occurring, a show format is usually created (Figure 5.2) that lists the program segments (scenes) and shows the following:

![]() The topic (such as a guitar solo)

The topic (such as a guitar solo)

![]() The amount of time allocated for this specific segment

The amount of time allocated for this specific segment

![]() The names of all talent involved (hosts and guests)

The names of all talent involved (hosts and guests)

![]() Facilities (cameras, audio, and any other equipment and space needed)

Facilities (cameras, audio, and any other equipment and space needed)

![]() External content sources that will be required (tape, digital, satellite, etc.)

External content sources that will be required (tape, digital, satellite, etc.)

FIGURE 5.2

Sample show format.

When segments (or edited packages) have been previously recorded to be inserted into the program, the script may show the opening and closing words of each segment and the package’s duration, which enables accurate cueing.

5.3 BASIC SCRIPT FORMATS

There are many different script formats. However, basically, script layouts take one of two forms:

![]() A single-column format

A single-column format

![]() A two-column format

A two-column format

Single-Column Format

Although there are variations of the single-column format (Figure 5.3), all video and audio information is usually contained in a single main column. Before each scene, an explanatory introduction describes the location and the action.

FIGURE 5.3

Single-column format/single-camera shooting script.

Reminder notes can be made in a wide left-hand margin. They include transition symbols (for example, x = cut; FU = fade-up), indicate cues and camera instructions, and incorporate thumbnail sketches of shots or action.

This type of script is widely used for narrative film-style production and single-camera video, where the director works alongside the camera operator. It is perhaps less useful in a multicamera setup, where the production team is more dispersed but everyone needs to know the director’s production intentions.

Two-Column Format

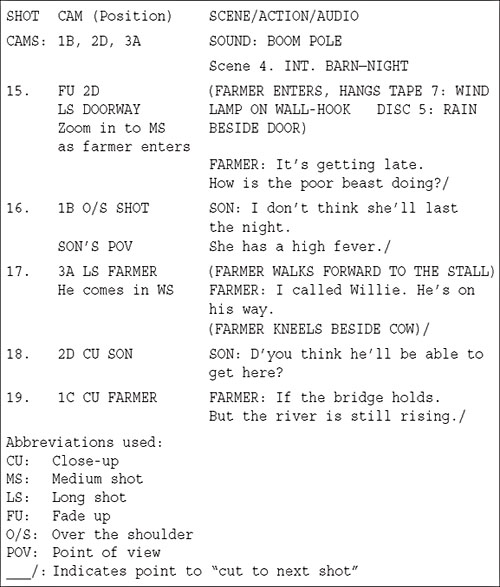

Like the one-column format, there are many variations of the two-column format (Figure 5.4). This traditional television format is extremely flexible and informative. It gives all members of the production crew shot-by-shot details of what is going on. Crew members can also add their own specific information (e.g., details of lighting changes) as needed.

Two versions of the script are sometimes prepared. In the first (rehearsal script) the right column only is printed. Subsequently, after detailed planning and preproduction rehearsals, the production details are added to the left column to form the camera script.

5.4 THE FULL SCRIPT

When a program is fully scripted, it includes detailed information on all aspects of the production.

![]() Scenes. Most productions are divided into a series of scenes. Each scene covers a complete continuous action sequence and is identified with a number and location (scene 3: Office set). A scene can involve anything from an interview to a dance routine, a song, or a demonstration sequence.

Scenes. Most productions are divided into a series of scenes. Each scene covers a complete continuous action sequence and is identified with a number and location (scene 3: Office set). A scene can involve anything from an interview to a dance routine, a song, or a demonstration sequence.

![]() Shots. When the director has decided how he or she is going to interpret the script, each scene is subdivided into a series of shots, each shot showing the action from a specific viewpoint. The shots are then numbered consecutively for easy reference on the script, in the order in which they will be screened. In a live production, the program is shot in the scripted order (running order). When taping a production, the director can shoot in whatever order is most convenient (shooting order) for the crew, actors, or director. The director may decide to omit shots (“drop shot 25”) or to add extra shots (“add shots 24A and 24B”). He or she may decide to record shot 50 before shot 1 and then edit them into the correct running order at a later time.

Shots. When the director has decided how he or she is going to interpret the script, each scene is subdivided into a series of shots, each shot showing the action from a specific viewpoint. The shots are then numbered consecutively for easy reference on the script, in the order in which they will be screened. In a live production, the program is shot in the scripted order (running order). When taping a production, the director can shoot in whatever order is most convenient (shooting order) for the crew, actors, or director. The director may decide to omit shots (“drop shot 25”) or to add extra shots (“add shots 24A and 24B”). He or she may decide to record shot 50 before shot 1 and then edit them into the correct running order at a later time.

![]() Dialog. The entire prepared dialog, spoken to camera or between people. (The talent may memorize the script or read it off teleprompters or cue cards.)

Dialog. The entire prepared dialog, spoken to camera or between people. (The talent may memorize the script or read it off teleprompters or cue cards.)

![]() Equipment. The script usually indicates which camera/microphone is being used for each shot (e.g., cam. 2. Fishpole).

Equipment. The script usually indicates which camera/microphone is being used for each shot (e.g., cam. 2. Fishpole).

![]() Basic camera instructions. Basicdetails of each shot and camera moves (e.g., cam. 1. CU on Joe’s hand; dolly out to long shot).

Basic camera instructions. Basicdetails of each shot and camera moves (e.g., cam. 1. CU on Joe’s hand; dolly out to long shot).

![]() Switcher (vision mixer)instructions. For example: cut, fade.

Switcher (vision mixer)instructions. For example: cut, fade.

![]() Contributory sources. Details of where videotape, graphics, remote feeds, and so forth appear in the program.

Contributory sources. Details of where videotape, graphics, remote feeds, and so forth appear in the program.

FIGURE 5.4

Two-column format/multicamera shooting script.

TIPS

Tips for writing better dialog: keeping it brief

Writing better dialog frequently means removing existing dialog and replacing it with action, or substituting action before putting any dialog down. All writers have to seriously acquaint themselves with the great films of the silent era and how the Sennett two-reelers and the Chaplin shorts moved forward and kept the audience rapt. There is a set of ground rules. The great writers of today are not really doing anything different than the silent era gag writers. The secret? Brevity.

The stage loves words; television and the cinema love movement. Say what you want to say in the briefest possible way. If that means taking out an entire speech and replacing it with an arched eyebrow, do so. If you have to choose between the two, an arched eyebrow packs a greater punch.

Gangster plots and love stories: Why is the gangster genre so enduring? One of the reasons is because the gangster has to think half a second faster than his adversary; often his life depends on it. A nod speaks volumes; a facial tick can bring down an empire. This approach can guide writers to write more effective dialog in all other genres (love stories included). In the gangster picture, the dialog is qualitative, not quantitative.

As an exercise, try writing a classic vignette (8 to 10 minutes long), a la Mack Sennett or Buster Keaton. Note that silent movies have little to no dialog (except for, perhaps, a few title cards) and are composed of almost pure action. As with all visual writing, your character has to get from A to B using the shortest route possible; the obstacles create the tension and drama. The writer can create a tension-filled scenario where the protagonist has to get from A to B using no dialog. These circumstances could include a prison break, a prom date, or anything with obstacles to overcome. This is a great exercise for keeping the creative muscles in shape.

—Sabastian Corbascio, Writer and Director

5.5 THE DRAMA SCRIPT

The dramatic full script may be prepared in two stages: the rehearsal script and the camera script.

The rehearsal script usually begins with general information sheets, including a cast/character list, production team details, and rehearsal arrangements. There may be a synopsis of the plot or story line, particularly when scenes are to be shot/recorded out of order. The rehearsal script includes full details of the following elements:

![]() Location. The setting where the scene will be shot.

Location. The setting where the scene will be shot.

![]() Time of day and weather conditions.

Time of day and weather conditions.

![]() Stage or location instructions. For example, “The room is candlelit, and the log fire burns brightly. “

Stage or location instructions. For example, “The room is candlelit, and the log fire burns brightly. “

![]() Action. Basic information on what is going to happen in the scene (i.e., actors’ moves: Joe lights a cigar).

Action. Basic information on what is going to happen in the scene (i.e., actors’ moves: Joe lights a cigar).

![]() Dialog. Speaker’s name (character) followed by the person’s dialog. This includes all delivered speech, voiceovers, voice inserts (e.g., phone conversations), commentary, announcements, and so on (perhaps with directional comments such as “sadly” or “sarcastically”).

Dialog. Speaker’s name (character) followed by the person’s dialog. This includes all delivered speech, voiceovers, voice inserts (e.g., phone conversations), commentary, announcements, and so on (perhaps with directional comments such as “sadly” or “sarcastically”).

![]() Effects cues. Indicates the moment for a change to take place (lightning flash, explosion, Joe switches light out).

Effects cues. Indicates the moment for a change to take place (lightning flash, explosion, Joe switches light out).

![]() Audio instructions. Amusic and sound effects.

Audio instructions. Amusic and sound effects.

The camera script adds full details of the production treatment to the left side of the rehearsal script and usually includes the following:

![]() The shot number

The shot number

![]() The camera used for the shot and possibly the position of the camera

The camera used for the shot and possibly the position of the camera

![]() Basic shot details and camera moves (CU on Joe; dolly back to a long shot LS as he rises)

Basic shot details and camera moves (CU on Joe; dolly back to a long shot LS as he rises)

![]() Switcher instructions (cut, dissolve, etc.)

Switcher instructions (cut, dissolve, etc.)

5.6 SUGGESTIONS ON SCRIPTWRITING

There are no shortcuts to good scriptwriting, any more than there are to writing short stories, composing music, or painting a picture. Scriptwriters learn their techniques through observation, experience, and reading. But there are general guides that are worth keeping in mind as you prepare your script.

5.7 BE VISUAL

Although audio and video images are both important in a production, viewers perceive television as primarily a visual medium. Material should be presented in visual terms as much as possible. If planned and shot well, the images can powerfully move the audience, sometimes with very few words. At other times, programs rely almost entirely on the audio, using the video images to strengthen, support, and emphasize what the audience hears. Visual storytelling is difficult but powerful when done well.

When directors want their audience to concentrate on what they are hearing, they try to make the picture less demanding. If, for instance, the audience is listening to a detailed argument and trying to read a screen full of statistics at the same time, they may do neither successfully.

5.8 ASSIMILATION

Production scripts should be developed as a smooth-flowing sequence that makes one point at a time. Avoid the tempting diversions that distract the audience from the main theme. As much as possible, try not to move back and forth between one subject and another. Directors need to avoid the three-ring circus effect, which can occur when they are trying to cover several different activities simultaneously. Ideally, one sequence should seem to lead naturally on to the next.

FIGURE 5.5

There are many different computer-based scriptwriting programs. The first photo shows a screen shot of Final Draft software and a script. The second photo shows a smart phone script writing app.

The previous paragraph presented a number of important points, but if a director presented ideas at that rate in a video program, there is a good chance that the audience would forget most of the information. Unlike them, you can read this book at your own pace, stop, and reread whatever you like. The audience viewing a video usually cannot. An essential point to remember when scripting is the difference between the rates at which we can take in information. A lot depends, of course, on how familiar the audience already is with the subject and the terms used. When details are new and the information is complicated, the director must take more time to communicate the information in a meaningful way. Ironically, something that can seem difficult and involved at the first viewing can appear slow and obvious a few viewings later. That is why it is so hard for directors to estimate the effect of material on those who are going to be seeing it for the first time. Directors become so familiar with the subject matter that they know it by heart and lose their objectivity.

Directors must simplify. The more complex the subject, the easier each stage should be. If the density of information or the rate at which it is delivered is too high, it will confuse, bewilder, or encourage the audience to switch it off—mentally if not physically.

5.9 RELATIVE PACE

As sequences are edited together, editors find that video images and the soundtrack have their own natural pace. That pace may be slow and leisurely, medium, fast, or brief. If editors are fortunate, the pace of the picture and the sound will be roughly the same. However, there will be occasions when editors find that they do not have enough images to fit the sound sequence or do not have enough soundtrack to put behind the amount of action in the picture.

Often when the talent has explained a point (perhaps taking 5 seconds), the picture is still showing the action (perhaps 20 seconds). The picture or action needs to finish before the commentary can move on to the next point. In the script, a little dialog may go a long way, as a series of interjections rather than a continual flow of verbiage.

The reverse can happen too, where the action in the picture is brief. For example, a locomotive passes through the shot in a few seconds, quicker than it takes the talent to talk about it. So more pictures of the subject are needed, from another viewpoint perhaps, to support the dialog.

Even when picture and sound are more or less keeping the same pace, do not habitually cut to a new shot as soon as the action in the picture is finished. Sometimes it is better to continue the picture briefly, to allow time for the audience to process the information that they have just seen and heard, rather than to move on with fast cutting and a rapid commentary.

It is all too easy to overload the soundtrack. Without pauses, a commentary can become an endless barrage of information. Moreover, if the editor has a detailed script that fits in with every moment of the image and the talent happens to slow down at all, the words can get out of step with the key shots they relate to. Then the editor has to either cut parts of the commentary or build out the picture (with appropriate shots) to bring the picture and sound back into sync.

5.10 STYLE

The worst type of script for video is the type that has been written in a formal literary style, as if for a newspaper article or an essay, where the words, phrases, and sentence construction are those of the printed page. When read aloud, this type of script tends to sound like an official statement or a pronouncement rather than the fluent everyday speech that usually communicates best with a television audience. This is not to say, of course, that we want a script that is so colloquial that it includes all the hesitations and slangy half-thoughts one tends to use, but we certainly prefer one that avoids complex sentence construction.

It takes some experience to be able to read any script fluently with the natural expression that brings it alive. But if the script itself is written in a stilted style, it is unlikely to improve with hearing. The material should be presented as if the talent is talking to an individual in the audience, rather than proclaiming on a stage or addressing a public meeting.

The way the information is delivered can influence how interesting the subject seems to be. The mind boggles at “the retainer lever actuates the integrated contour follower.” But we immediately understand “Here you can see, as we pull this lever, the lock opens.”

If the audience has to pause to figure out what the speaker means, they will not be listening closely to what the person is saying. Directors can often assist the audience by anticipating the problems and then inserting a passing explanation, a subtitle (especially useful for names), or a simple diagram.

5.11 TIPS ON DEVELOPING THE SCRIPT

How scripts are developed varies with the type of program and the way individual directors work. The techniques and processes of good script writing are a study in themselves, but we can take a look at some of the guiding principles and typical points that need to be considered.

The Nature of the Script

![]() The script may form the basis of the entire production treatment.

The script may form the basis of the entire production treatment.

Here the production is staged, performed, and shot as indicated in the script. As far as possible, dialog and action follow the scripted version.

![]() The scriptwriter may prepare a draft script (i.e., a suggested treatment).

The scriptwriter may prepare a draft script (i.e., a suggested treatment).

The director studies and develops this draft to form a shooting script.

![]() The script may be written after material has been shot.

The script may be written after material has been shot.

Certain programs, such as documentaries, may be shot to a preconceived outline plan, but the final material will largely depend on the opportunities of the moment. The script is written to blend this material together in a coherent story line, adding explanatory commentary/dialog. Subsequent editing and postproduction work based on this scripted version.

![]() The script may be written after material has been edited.

The script may be written after material has been edited.

Here the videotape editor assembles the shot material, creating continuity and a basis for a story line. The script is then developed to suit the edited program.

Occasionally, a new script may replace the program’s original script with new or different text. For example, when the original program was made in a language that differs from that of the intended audience, it may be marketed as an M&E version, in which the soundtrack includes only “music and effects.” All dialog or voiceover commentary is added (dubbed in) later by the recipient in another language.

Scriptwriting Basics

A successful script has to satisfy two important requirements:

![]() It must fulfill the program’s main purpose. For example, it must be able to amuse, inform, intrigue, or persuade (i.e., the artistic, aesthetic, dramatic element of the script).

It must fulfill the program’s main purpose. For example, it must be able to amuse, inform, intrigue, or persuade (i.e., the artistic, aesthetic, dramatic element of the script).

![]() It must be practical. The script must be a workable vehicle for the production crew.

It must be practical. The script must be a workable vehicle for the production crew.

Fundamentally, we need to ensure that the following occurs:

![]() The script meets its deadline. When is the script required? Is it for a specific occasion?

The script meets its deadline. When is the script required? Is it for a specific occasion?

![]() The treatment is feasible for the budget, facilities, and time available. An overambitious script will necessarily have to be rearranged, edited, and scenes rewritten to provide a workable basis for the production.

The treatment is feasible for the budget, facilities, and time available. An overambitious script will necessarily have to be rearranged, edited, and scenes rewritten to provide a workable basis for the production.

![]() The treatment fits the anticipated program length. Otherwise it will become necessary to cut sequences or pad the production with added scenes afterward to fit the show to the allotted time slot.

The treatment fits the anticipated program length. Otherwise it will become necessary to cut sequences or pad the production with added scenes afterward to fit the show to the allotted time slot.

![]() The style and the form of presentation are appropriate for the subject. An unsuitable style, such as a lighthearted approach to a serious topic, may trivialize the subject.

The style and the form of presentation are appropriate for the subject. An unsuitable style, such as a lighthearted approach to a serious topic, may trivialize the subject.

![]() The subject treatment is suitable for the intended audience. The style, complexity, concentration of information, and so on must be relative to their probable interest and attention span.

The subject treatment is suitable for the intended audience. The style, complexity, concentration of information, and so on must be relative to their probable interest and attention span.

Ask Yourself These Questions

Who is the program for?

![]() What is our target age group? (e.g., children, college classes, mature students)

What is our target age group? (e.g., children, college classes, mature students)

![]() Are the audience members specialists? (e.g., sales staff, teachers, hobbyists)

Are the audience members specialists? (e.g., sales staff, teachers, hobbyists)

![]() Where is it to be shown? (e.g., classroom, home, theater, public place)

Where is it to be shown? (e.g., classroom, home, theater, public place)

![]() What display device will be used? (e.g., television, I-mag screens, online, mobile telephone)

What display device will be used? (e.g., television, I-mag screens, online, mobile telephone)

What is the purpose of this program?

![]() Is it for entertainment, information, or instruction?

Is it for entertainment, information, or instruction?

![]() Is it intended to persuade? (as in advertising, program trailers, propaganda)

Is it intended to persuade? (as in advertising, program trailers, propaganda)

![]() Is there a follow-up to the program? (publicity offers, tests)

Is there a follow-up to the program? (publicity offers, tests)

Is the program one of a series?

![]() Does it relate to or follow other programs?

Does it relate to or follow other programs?

![]() Do viewers need to be reminded of past information?

Do viewers need to be reminded of past information?

![]() Does the script style need to be similar to previous programs?

Does the script style need to be similar to previous programs?

![]() Were there any omissions, weaknesses, or errors in previous programs we can correct in this program?

Were there any omissions, weaknesses, or errors in previous programs we can correct in this program?

What does the audience already know?

![]() Is the audience familiar with the subject?

Is the audience familiar with the subject?

![]() Does the audience understand the terms used?

Does the audience understand the terms used?

![]() Is the information complicated?

Is the information complicated?

![]() Does previous information need to be recapped?

Does previous information need to be recapped?

![]() Would a brief outline or introduction help (or remind) the audience?

Would a brief outline or introduction help (or remind) the audience?

![]() Is the audience likely to be prejudiced for or against the subject or the product? (e.g., necessitating diplomacy or careful unambiguous treatment)

Is the audience likely to be prejudiced for or against the subject or the product? (e.g., necessitating diplomacy or careful unambiguous treatment)

What is the length of the program?

![]() Is it brief? (having to make an immediate impact)

Is it brief? (having to make an immediate impact)

![]() Is it long enough to develop arguments or explanations for a range of topics?

Is it long enough to develop arguments or explanations for a range of topics?

How much detail is required in the script?

![]() Is the script to be complete, with dialog and action? (actual visual treatment depends on the director)

Is the script to be complete, with dialog and action? (actual visual treatment depends on the director)

![]() Is the script a basis for improvisation? (e.g., by a guide or lecturer)

Is the script a basis for improvisation? (e.g., by a guide or lecturer)

![]() Is it an ideas sheet, giving an outline for treatment?

Is it an ideas sheet, giving an outline for treatment?

Are you writing dialog?

![]() Is it for actors or inexperienced performers to read? (for the latter, keep it brief, in short “bites” to be read from a prompter or spoken in the performer’s own words)

Is it for actors or inexperienced performers to read? (for the latter, keep it brief, in short “bites” to be read from a prompter or spoken in the performer’s own words)

![]() Is the dialog to be naturalistic or “character dialog”?

Is the dialog to be naturalistic or “character dialog”?

Is the subject a visual one?

![]() If the subjects are abstract or no longer exist, how will you illustrate them?

If the subjects are abstract or no longer exist, how will you illustrate them?

Have you considered the script’s requirements?

![]() It only takes a few words on the page to suggest a situation, but reproducing it in pictures and sound may require considerable time, expense, and effort (e.g., a battle scene); you may have to rely on available stock library video.

It only takes a few words on the page to suggest a situation, but reproducing it in pictures and sound may require considerable time, expense, and effort (e.g., a battle scene); you may have to rely on available stock library video.

![]() Does the script pose obvious problems for the director? (e.g., a script involving special effects, stunts, etc.)

Does the script pose obvious problems for the director? (e.g., a script involving special effects, stunts, etc.)

![]() Does the script involve costly concepts that can be simplified? (e.g., an intercontinental conversation could be covered by an expensive two-way video satellite transmission, or it can be accomplished by utilizing a telephone call accompanied by previously acquired footage or still images)

Does the script involve costly concepts that can be simplified? (e.g., an intercontinental conversation could be covered by an expensive two-way video satellite transmission, or it can be accomplished by utilizing a telephone call accompanied by previously acquired footage or still images)

Does the subject involve research?

![]() Does the script depend on what researchers discover while investigating the subject?

Does the script depend on what researchers discover while investigating the subject?

![]() Do you already have information that can aid the director? (have contacts, know of suitable locations, availability of insert material, etc.)

Do you already have information that can aid the director? (have contacts, know of suitable locations, availability of insert material, etc.)

Where will the images come from?

![]() Will the subjects be brought to the studio (which allows maximum control over the program treatment and presentation) or will cameras be going on location to the subjects? (this may include shooting in museums, etc.); script opportunities may depend on what is available when the production is being shot.

Will the subjects be brought to the studio (which allows maximum control over the program treatment and presentation) or will cameras be going on location to the subjects? (this may include shooting in museums, etc.); script opportunities may depend on what is available when the production is being shot.

Remember

Start scripting with a simple outline.

![]() Before embarking on the main script treatment, it can be particularly helpful to rough out a skeleton version. This would usually include a general outline treatment that covers the various points that need to be included, in the order in which the director proposes to deal with them.

Before embarking on the main script treatment, it can be particularly helpful to rough out a skeleton version. This would usually include a general outline treatment that covers the various points that need to be included, in the order in which the director proposes to deal with them.

Be visual.

![]() Sometimes pictures alone can convey the information more powerfully than the spoken word.

Sometimes pictures alone can convey the information more powerfully than the spoken word.

![]() The way a commentary is written (and spoken) can influence how the audience interprets a picture (and vice versa).

The way a commentary is written (and spoken) can influence how the audience interprets a picture (and vice versa).

![]() Pictures can distract. People may concentrate more on looking than on listening!

Pictures can distract. People may concentrate more on looking than on listening!

![]() Avoid “talking heads” wherever possible. Show the subject being talked about rather than the person who is speaking.

Avoid “talking heads” wherever possible. Show the subject being talked about rather than the person who is speaking.

![]() The script can only indicate visual treatment. It will seldom be specific about shot details unless that is essential to the plot or situation. Directors have their own ideas!

The script can only indicate visual treatment. It will seldom be specific about shot details unless that is essential to the plot or situation. Directors have their own ideas!

Avoid overloading.

![]() Keep it simple. Don’t be long-winded or use complicated sentences. Keep to the point. When a subject is difficult, an accompanying diagram, chart, or graph may make the information easier to understand.

Keep it simple. Don’t be long-winded or use complicated sentences. Keep to the point. When a subject is difficult, an accompanying diagram, chart, or graph may make the information easier to understand.

![]() Do not give too much information at a time. Do not attempt to pack too much information into the program. It is better to do justice to a few topics than to cover many inadequately.

Do not give too much information at a time. Do not attempt to pack too much information into the program. It is better to do justice to a few topics than to cover many inadequately.

Develop a flow of ideas.

![]() Deal with one subject at a time. Generally avoid cutting between different topics, flashbacks, and flash forwards.

Deal with one subject at a time. Generally avoid cutting between different topics, flashbacks, and flash forwards.

![]() If the screen has text to be read, either have an unseen voice read the same information or give the viewer enough time to read it.

If the screen has text to be read, either have an unseen voice read the same information or give the viewer enough time to read it.

![]() Do not have different information on the screen and in the commentary. This can be distracting and confusing to the viewer.

Do not have different information on the screen and in the commentary. This can be distracting and confusing to the viewer.

![]() Aim to have one subject or sequence lead naturally into the next.

Aim to have one subject or sequence lead naturally into the next.

![]() Where there are a number of topics, think through how they are related and the transitions necessary to keep the audience’s interest.

Where there are a number of topics, think through how they are related and the transitions necessary to keep the audience’s interest.

Develop a pace.

![]() Vary the pace of the program. Avoid a fast pace when imparting facts. It conveys an overall impression, but facts do not sink in. A slow pace can be boring or restful, depending on the content.

Vary the pace of the program. Avoid a fast pace when imparting facts. It conveys an overall impression, but facts do not sink in. A slow pace can be boring or restful, depending on the content.

![]() Remember that the audience cannot refer back to the program (unless it is interactive). If they miss a point, they may fail to understand the next point and will probably lose interest.

Remember that the audience cannot refer back to the program (unless it is interactive). If they miss a point, they may fail to understand the next point and will probably lose interest.

Develop a style.

![]() Use an appropriate writing style for the intended viewer. Generally aim at an informal, relaxed style.

Use an appropriate writing style for the intended viewer. Generally aim at an informal, relaxed style.

![]() There is a world of difference between the style of the printed page and the way people normally speak. When you read from a prompter, it produces an unnatural, stilted effect.

There is a world of difference between the style of the printed page and the way people normally speak. When you read from a prompter, it produces an unnatural, stilted effect.

![]() Be careful about introducing humor into the script.

Be careful about introducing humor into the script.

Interview with a Pro

Robyn Sjogren, Writer

Robyn Sjogren, Writer

What do you like about being a writer?

![]() I like the creativity that’s involved with writing. There’s always an empty slate to work with, and, within reason, you can craft the script however you want. It really can be fun!

I like the creativity that’s involved with writing. There’s always an empty slate to work with, and, within reason, you can craft the script however you want. It really can be fun!

![]() I like the aspect of informing the public about current events. It’s a public service. My writing has the potential to help someone else change the world, find a missing child, or compel them to write to their government leaders to address an important issue that needs changing.

I like the aspect of informing the public about current events. It’s a public service. My writing has the potential to help someone else change the world, find a missing child, or compel them to write to their government leaders to address an important issue that needs changing.

How do you write visually for TV?

![]() You have to really think about the video the viewer will see when you write your copy.

You have to really think about the video the viewer will see when you write your copy.

![]() Write to the video. When appropriate, go ahead and describe what the viewer is seeing.

Write to the video. When appropriate, go ahead and describe what the viewer is seeing.

What suggestions do you have for new writers?

![]() Be conversational. Write like you’re writing to a friend as much as possible.

Be conversational. Write like you’re writing to a friend as much as possible.

![]() Read the wirecopy first, and then try to write without it. You can always go back to check for facts, but this way you’re not leaning on the wirecopy as a crutch. Chances are, your writing will be more conversational in the end.

Read the wirecopy first, and then try to write without it. You can always go back to check for facts, but this way you’re not leaning on the wirecopy as a crutch. Chances are, your writing will be more conversational in the end.

![]() Read what you’ve written out loud. If it sounds “newsy,” it’s not conversational enough.

Read what you’ve written out loud. If it sounds “newsy,” it’s not conversational enough.

![]() Put the best details first. Sometimes the new stuff isn’t the best stuff. Sell the viewer on the story. Practice! The more you write, the better you will get. You will get faster and more comfortable with it as well.

Put the best details first. Sometimes the new stuff isn’t the best stuff. Sell the viewer on the story. Practice! The more you write, the better you will get. You will get faster and more comfortable with it as well.

![]() Short sentences are key so the anchor has a chance to breathe. It also makes it more conversational.

Short sentences are key so the anchor has a chance to breathe. It also makes it more conversational.

What are some challenges that you face as a writer?

![]() One of the biggest challenges is writing for “Day 2” or 3, or 4, and so on. The challenge is to keep the story current, but not boring and avoiding words like “another,” “still,” “continues,” etc.

One of the biggest challenges is writing for “Day 2” or 3, or 4, and so on. The challenge is to keep the story current, but not boring and avoiding words like “another,” “still,” “continues,” etc.

![]() Sometimes the story isn’t something you’d tell to a friend, but you still have to make it conversational. That’s a big challenge.

Sometimes the story isn’t something you’d tell to a friend, but you still have to make it conversational. That’s a big challenge.

__________________________________

Robyn Sjogren is a writer for CNN and TruTV.