CHAPTER 6

The Camera

Perhaps it sounds ridiculous, but the best thing that young filmmakers should do is to get hold of a camera and shoot and make a movie of any kind at all.

—Stanley Kubrick, Director

Camera operators need to know their camera so well that they don’t need to “think” about it technically. That knowledge allows them to spend their time shooting creatively in a way that effectively communicates.

Key Terms

![]() Aperture: The opening of the iris (see iris).

Aperture: The opening of the iris (see iris).

![]() CCD: This charged-coupled device is an image sensor used in most video cameras.

CCD: This charged-coupled device is an image sensor used in most video cameras.

![]() CMOS: This complementary metal-oxide semiconductor image sensor has less power consumption, saving energy for longer shooting times.

CMOS: This complementary metal-oxide semiconductor image sensor has less power consumption, saving energy for longer shooting times.

![]() Depth of field: The distance between the nearest and farthest objects in focus.

Depth of field: The distance between the nearest and farthest objects in focus.

![]() Digital zoom: Zooming is achieved by progressively reading out a smaller and smaller area of the same digitally constructed image. The image progressively deteriorates as the digital zoom is zoomed in.

Digital zoom: Zooming is achieved by progressively reading out a smaller and smaller area of the same digitally constructed image. The image progressively deteriorates as the digital zoom is zoomed in.

![]() Dolly: This platform with wheels is used to smoothly move a camera during a shot toward or away from the talent. Dolly also refers to a movement of the camera closer to, or further away from, the subject.

Dolly: This platform with wheels is used to smoothly move a camera during a shot toward or away from the talent. Dolly also refers to a movement of the camera closer to, or further away from, the subject.

![]() DSLR: Digital Single Lens Reflex still camera with video capabilities.

DSLR: Digital Single Lens Reflex still camera with video capabilities.

![]() f-stop: The measurement of the size of the aperture.

f-stop: The measurement of the size of the aperture.

![]() Focal length: An optical measurement; the distance between the optical center of the lens and the image sensor, when you are focused at a great distance such as infinity; it is measured in millimeters (mm) or inches.

Focal length: An optical measurement; the distance between the optical center of the lens and the image sensor, when you are focused at a great distance such as infinity; it is measured in millimeters (mm) or inches.

![]() Handheld camera: A camera that is held by a person and not supported by any type of camera mount.

Handheld camera: A camera that is held by a person and not supported by any type of camera mount.

![]() Iris: The diaphragm of the lens that is adjustable. This diaphragm is adjusted open or closed based on the amount of light needed to capture a quality image.

Iris: The diaphragm of the lens that is adjustable. This diaphragm is adjusted open or closed based on the amount of light needed to capture a quality image.

![]() Jib: A counterbalanced arm that fits onto a tripod that allows the camera to move up, down, and around.

Jib: A counterbalanced arm that fits onto a tripod that allows the camera to move up, down, and around.

![]() Normal lens: The type of lens that portrays the scene approximately the same way a human eye might see it.

Normal lens: The type of lens that portrays the scene approximately the same way a human eye might see it.

![]() Optical zoom: The optical zoom uses a lens to maintain a high-quality image throughout its zoom range.

Optical zoom: The optical zoom uses a lens to maintain a high-quality image throughout its zoom range.

![]() Prime lens: A lens that has a fixed focal length.

Prime lens: A lens that has a fixed focal length.

![]() Telephoto lens: Gives a magnified view of the scene, making it appear closer.

Telephoto lens: Gives a magnified view of the scene, making it appear closer.

![]() Tripod: A camera mount that is a three-legged stand with independently extendable legs.

Tripod: A camera mount that is a three-legged stand with independently extendable legs.

![]() Tripod arms (pan bars): Handles that attach to the pan head on a tripod or other camera mount to accurately pan, tilt, and control the camera.

Tripod arms (pan bars): Handles that attach to the pan head on a tripod or other camera mount to accurately pan, tilt, and control the camera.

![]() Truck: The truck, trucking, or tracking shot is when the camera and mount move sideways with the subject.

Truck: The truck, trucking, or tracking shot is when the camera and mount move sideways with the subject.

![]() Viewfinder: Monitors the camera’s picture. This allows the camera operator to focus, zoom, and frame the image.

Viewfinder: Monitors the camera’s picture. This allows the camera operator to focus, zoom, and frame the image.

![]() Wide-angle lens: Shows a greater area of the scene.

Wide-angle lens: Shows a greater area of the scene.

![]() Zoom lens: A lens that has a variable focal length.

Zoom lens: A lens that has a variable focal length.

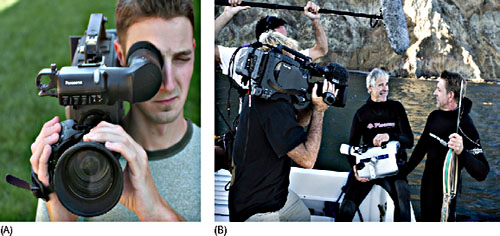

6.1 A RANGE OF MODELS

Video cameras today come in a wide variety of shapes and sizes that suit all kinds of different situations. They range from units that fit in a pocket to cameras that are so heavy that they can take a couple of people to lift them (Figure 6.1). Historically there were consumer, industrial, and professional cameras. Many of those monikers have merged, with small, previously thought of as “consumer” cameras now being used in the professional workplace (Figure 6.2). Traditionally, for a multicamera production, high-cost cameras were used that required camera control units. Today’s multicamera systems allow many types of cameras to be used in professional situations, including low-cost cameras. The right camera depends on how the end production is going to be used. What was considered a professional quality camera 10 years ago has been dwarfed by the quality of small, low-cost high-definition pocket-sized cameras available today. Television and film competitions are being won by directors who are using cameras that cost less than $1,000. That was unheard of in the 1990s. So now, no one can blame the lack of quality on his or her camera gear because almost anyone can afford the equipment. For all of the cool technological advancements, keep in mind that the important thing is to know how to visually communicate.

Most productions are created with a camera that is a stand-alone unit; they are known as single-camera productions. Single-camera productions are generally edited together during postproduction. The second major type of production is a multicamera production, where two or more cameras are used with a switcher selecting the image to be shown to the viewer, otherwise known as “live editing.” We will be covering both of these types of production in more detail in a later chapter.

FIGURE 6.1

Video cameras come in all different shapes and sizes.

(Photos courtesy of Grass Valley/Thomson, Sony, JVC, and Panasonic.)

FIGURE 6.2

Traditionally thought of as consumer cameras, small HD cameras, such as the GoPro shown, are now being used by television networks for specialty shots. These HD cameras have gained popularity as a camera that can be connected to anything. For a relatively low cost, this high-quality little camera, with a 170 wide-angle lens and waterproof case, records to an SD card. The photo on the right was shot with this camera.

Single cameras generally have a built-in recorder. Cameras are increasingly moving away from videotape. Most cameras today use a flash card and/or a hard drive. Cameras may also be combined (by wire or wirelessly) with other recorders, such as a tape deck or a portable hard drive. Some of the studio cameras or remote production (outside broadcast) cameras are available without recorders because they are designed specifically for multicamera use (Figures 6.2, 6.3, and 6.4).

FIGURE 6.3

With their high-resolution sensors and HD capabilities, cell phones are becoming increasingly popular as video cameras. The iPhone 4 shown here is attached to an OWLE grip that includes tripod/light mounts, a professional mic, and an add-on wide-angle lens. One of the main advantages of these phones is that the video can easily be immediately edited on the phone and then transmitted back to a news station, client, or directly onto a website … right from the phone.

6.2 CAMERACRAFT

Most video cameras are easy to operate at the basic level. Designers have gone to a lot of trouble to make controls simple to use. The consumer-oriented cameras have been so automated that all one needs to do to get a decent image is to point them at the subject and press the record button. When shooting for fun, that’s fine. So why make camerawork any more complicated?

It really depends on whether the director plans to use the camera as a creative tool. The weakness of automatic controls is that the camera is only designed to make technical judgments. Many times these technical decisions are something of a compromise. The camera cannot make artistic choices of any kind. Auto-circuitry can help the camera operator avoid poor-quality video images, but it cannot be relied on to produce attractive and meaningful pictures. Communicating visually will always depend on how you use the camera and the choices you make.

Obviously, good production is much more than just getting the shot. It begins with the way the camera is handled and controlled. It is not just a matter of getting a sharp image but of selecting which parts of the scene are to be sharp and which are to be presented in soft focus. It involves carefully selecting the best angle and arranging the framing and composition for maximum impact, as well as deciding what is to be included in the shot and what is to be left out. It is the art of adjusting the image tones by careful exposure. Automatic camera circuitry can help, particularly when shooting under difficult conditions, and can save the camera operator from having to worry about technicalities. However, automatic circuitry cannot create meaningful images. Let’s take a look at the parts of a camera.

ENG/EFP Camera Components

![]() This type of viewfinder is generally called an electronic news gathering (ENG) or electronic field production (EFP) viewfinder. It is a small monitor designed to be placed next to the camera operator’s eye.

This type of viewfinder is generally called an electronic news gathering (ENG) or electronic field production (EFP) viewfinder. It is a small monitor designed to be placed next to the camera operator’s eye.

![]() The power switch turns the camera on/off.

The power switch turns the camera on/off.

![]() The manual zoom control lens ring allows the camera operator to zoom in and out manually.

The manual zoom control lens ring allows the camera operator to zoom in and out manually.

![]() The power zoom rocker switch, located on the side of the lens, allows the camera operator to electronically zoom the lens. The speed of the zoom may vary, depending on the switch pressure.

The power zoom rocker switch, located on the side of the lens, allows the camera operator to electronically zoom the lens. The speed of the zoom may vary, depending on the switch pressure.

![]() The ocus control ring on a lens allows the camera operator to turn the ring manually to obtain the optimal focus.

The ocus control ring on a lens allows the camera operator to turn the ring manually to obtain the optimal focus.

![]() The lens aperture control ring allows the camera operator to adjust the lens iris manually to control exposure.

The lens aperture control ring allows the camera operator to adjust the lens iris manually to control exposure.

![]() The white and black balance controls the circuitry in the camera that uses white or black to balance the color settings of the camera.

The white and black balance controls the circuitry in the camera that uses white or black to balance the color settings of the camera.

![]() The filter wheel includes a number of filters that can be used to correct the color in daylight, tungsten, and fluorescent lighting situations.

The filter wheel includes a number of filters that can be used to correct the color in daylight, tungsten, and fluorescent lighting situations.

![]() Clip-on camera batteries allow the camera operator to carry multiple batteries.

Clip-on camera batteries allow the camera operator to carry multiple batteries.

![]() Although at this point it is not common, some cameras are equipped with a built-in wireless microphone and antennas.

Although at this point it is not common, some cameras are equipped with a built-in wireless microphone and antennas.

![]() On-camera shotgun microphones are useful for picking up natural sound but often pick up camera and operator noises.

On-camera shotgun microphones are useful for picking up natural sound but often pick up camera and operator noises.

![]() Lens shades protect the lens elements from picking up light distortions from the sun or a bright light.

Lens shades protect the lens elements from picking up light distortions from the sun or a bright light.

FIGURE 6.4

A number of different 3D cameras have been introduced, including a low-cost professional model (A) and a very low-cost consumer model (B).

(Photos courtesy of Panasonic.)

FIGURE 6.5

Video camera designs vary, but these are some of the common parts found in a professional ENG camera.

(Photo courtesy of Panasonic.)

FIGURE 6.6

Parts of a high-quality (4K) camera.

(Photo courtesy of Rd.)

Stationary/Hard/Studio Camera Components

FIGURE 6.7

The “studio” or “hard” camera body is attached to a pan head. The zoom lens is then attached to the camera body and the pan head. This type of system is generally used in studio or remote production settings where the camera is stationary.

![]() The camera cable is a two-way cable that carries the video to a distant camera control unit (CCU) and allows the video operator to adjust the camera from a remote site (such as studio control or a remote truck).

The camera cable is a two-way cable that carries the video to a distant camera control unit (CCU) and allows the video operator to adjust the camera from a remote site (such as studio control or a remote truck).

![]() The viewfinder (VF) monitors the camera’s picture. This allows the camera operator to focus, zoom, and frame the image.

The viewfinder (VF) monitors the camera’s picture. This allows the camera operator to focus, zoom, and frame the image.

![]() The quick-release mount is attached to the camera and fits into a corresponding recessed plate attached to the tripod/pan head. This allows the camera operator to quickly remove or attach the camera to the camera mount.

The quick-release mount is attached to the camera and fits into a corresponding recessed plate attached to the tripod/pan head. This allows the camera operator to quickly remove or attach the camera to the camera mount.

![]() The tripod head (panning head) enables the camera to tilt and pan smoothly. Variable friction controls (drag) steady these movements. The head can also be locked off in a fixed position. Tilt balance adjustments position the camera horizontally to assist in balancing the camera on the mount.

The tripod head (panning head) enables the camera to tilt and pan smoothly. Variable friction controls (drag) steady these movements. The head can also be locked off in a fixed position. Tilt balance adjustments position the camera horizontally to assist in balancing the camera on the mount.

![]() One or two tripod arms (or panning bars/handles) attached to the pan head allow the operator to accurately pan, tilt, and control the camera.

One or two tripod arms (or panning bars/handles) attached to the pan head allow the operator to accurately pan, tilt, and control the camera.

![]() The tripod, or camera mount can take various forms such as a tripod, pedestal, or jib.

The tripod, or camera mount can take various forms such as a tripod, pedestal, or jib.

![]() The zoom control (servo zoom), focus control, and remote controls allow the camera operator to zoom and focus the lens from behind the camera.

The zoom control (servo zoom), focus control, and remote controls allow the camera operator to zoom and focus the lens from behind the camera.

CAMERA FEATURES

6.3 MAIN FEATURES

Let’s take a look at the main sections of a camera (see Figure 6.8):

![]() The lens system focuses a small image of the scene onto a light-sensitive sensor.

The lens system focuses a small image of the scene onto a light-sensitive sensor.

![]() This light-sensitive chip, or sensor., converts the image from the lens into a corresponding pattern of electrical charges, which are read out to provide the video signal.

This light-sensitive chip, or sensor., converts the image from the lens into a corresponding pattern of electrical charges, which are read out to provide the video signal.

![]() The camera’s viewfinder displays the video image, enabling the camera operator to set up the shot, adjust focus, exposure, and so on.

The camera’s viewfinder displays the video image, enabling the camera operator to set up the shot, adjust focus, exposure, and so on.

![]() The camera’s recorder captures the video images and stores them on tape, flash memory, or hard drive.

The camera’s recorder captures the video images and stores them on tape, flash memory, or hard drive.

![]() The camera’s power supply is usually either an external Ac power supply that plugs into the wall or batteries that fit onto the camera.

The camera’s power supply is usually either an external Ac power supply that plugs into the wall or batteries that fit onto the camera.

![]() The Microphone is either fitted internally or attached onto the camera and is intended for general sound pickup.

The Microphone is either fitted internally or attached onto the camera and is intended for general sound pickup.

The instruction manual issued with the camera gives details and specifications of the specific model you are using. Table 6.1 presents a list of typical features.

FIGURE 6.8

The DSLR has become a popular choice as a video camera.

(Photo courtesy of Canon.)

| Gain control | Circuitry that manually or automatically adjusts video amplification to keep it within preset limits. Reduced during bright shots and increased under dimmer conditions, it alters overall picture brightness and contrast. |

| Auto-black | After capping the lens to exclude all light, this switch automatically sets the camera’s circuitry to produce a standard black reference level. |

| Auto-focus | A mechanism that automatically adjusts the lens focus for maximum sharpness on the nearest subject in a selected zone of the frame. Whether this is the one you want sharpest is another matter. When shooting through foreground objects, focusing selectively, or if anything is likely to move between the camera and your subject, the camera should be switched to manual focusing. This option is always available on consumer cameras and rarely part of a high-end professional camera. However, medium-level professional cameras seem to increasingly be adding this option. |

| Auto-iris | This device automatically adjusts the lens aperture (f-stop) to suit the prevailing light levels (light intensities). By doing so, it prevents the image from being very over- or underexposed (washed-out or murky). However, there are times when the auto-iris misunderstands and changes the lens aperture when it should remain constant, such as during zooming or when a lighter area comes into the shot. Then it is necessary to switch the lens aperture control to manual aperture and operate it by hand. |

| White balance or auto-white | This control automatically adjusts the camera circuits’ color-balance to suit the color quality of the prevailing light and ensure that white surfaces are accurately reproduced as neutral. Otherwise, all colors would be slightly warmer (red-orange) or colder (bluish) than normal, depending on the light source. To white-balance a camera, the operator pushes the white balance button while aiming the camera at a white surface (see Figure 6.5). |

| Backlight control | This control opens the lens aperture an arbitrary stop or so above that selected by the auto-iris system to avoid underexposure resulting from ambiguous readings. |

| Black stretch or gamma adjustment | Some cameras include an operator-controlled circuit adjustment to make shadow detail clearer and improve tonal gradation in darker picture tones. This is the opposite of “contrast compression,” which emphasizes the contrast in picture tones. With a higher gamma setting such as 1.0, picture tones are more contrasty, coarse, and dramatic. A lower gamma setting such as a 0.4 provides more subtle, flatter tonal quality. |

| These areas should be adjusted by someone who knows what he or she is doing and is utilizing a waveform monitor. | |

| Camera cable | This may be a short “umbilical” multiwire cable connecting the camera to a recorder or a more substantial cable routed to a camera control unit (CCU). This cable provides power, sync, intercom, and so on, to the camera, and takes video and audio from the camera to the main video/ audio equipment. |

| Color correction filters or filter wheel | Because the brain compensates, we tend to assume that most everyday light sources such as sunlight, tungsten light, quartz lamps, and candlelight are all producing “white” light. But in reality, these various luminants often have quite different color qualities. They may be bluish or reddish yellow, depending on the light source and the conditions. |

| Unless the camera’s color system is matched to the prevailing light, its pictures will appear unnaturally warm (orange) or cool (bluish). | |

| How far auto-white adjustment is able to rebalance the camera’s color response to compensate for variations in the color quality of the prevailing light depends on equipment design. For greater compensation, filters may be required to obtain the best color. These are often fitted inside the video camera, just behind the lens on a filter wheel. Alternatively, an appropriate filter may be fitted on the front of the lens. | |

| Typical correction filters include daylight (5600), artificial/tungsten light (3200), and fluorescent light (4700). The filter wheel may also include or combine neutral-density (ND) filters to improve exposure. | |

| Exposure modes | A series of preset savable exposure settings such as indoor/outdoor. |

| Exposure override | Switches from auto-iris system to manual to allow precise exposure adjustments. |

| Macro | Most zoom lenses have a macro position. This allows the lens to focus on very close objects—much closer than the lens’s normal minimum focused distance. |

| Photo mode | Some video cameras have the ability to capture still pictures (freeze frames) of a scene. |

| Image stabilizer | This system compensates for accidental irregular camera movements such as camera shake. |

| Preset situations | Some consumer cameras offer prearranged adjustments selected for typical occasions such as sport action or snowy conditions. These are general exposure selections and are not recommended for the serious camera operator. |

| Shutter speed | To avoid movement blur and improve detail in fast action, a much briefer exposure rate than the normal 1/60 sec (PAL 1/50) is needed. A variable highspeed electronic shutter (settings from, e.g., 1/125 to 1/400sec) reduces blur considerably but needs higher light levels. |

| Standby switch | This setting is used to save battery power by switching off unused units when rehearsing or during standby. Some cameras have auto switch-off, which cuts the system’s power when the camera has not been used for several minutes. |

| Timecode | This series of frame-accurate numbers is assigned to a specific video frame. The number includes hours, minutes, seconds, and elapsed frames. |

| Genlock input | When working as an ENG camera, the camera generates its own internal synchronizing pulses to stabilize the scanning circuits. Genlock allows external sync to be put into the camera. In multicamera production, a genlock cable may be plugged into the genlock input, using sync from a communal sync generator. |

THE DSLR (PROS AND CONS)

Digital Single Lens Reflex cameras (DSLR) have become a formidable force in the video world today. While originally they were designed as a still camera that has some video capability, directors are using them to shoot corporate videos, commercials, television network shows, and even feature films. Some camera model’s high megapixel sensors and 1080p quality, combined with their small size and low cost, make them a cost-effective option in video production. However, there are positives and negatives about the current class of DSLR cameras. While they are continually improving, the current models are good for some projects and not a good camera for other projects. Here are some of the pros and cons:

Advantages:

![]() Low cost: When compared to video cameras with similar image quality, the DSLR is very cost effective.

Low cost: When compared to video cameras with similar image quality, the DSLR is very cost effective.

![]() Depth-of-field: The large sensor size can provide a very shallow depth-of-field.

Depth-of-field: The large sensor size can provide a very shallow depth-of-field.

![]() Weight: Its light weight makes it easier to move around.

Weight: Its light weight makes it easier to move around.

![]() Low profile: When shooting documentaries, the camera is less obvious.

Low profile: When shooting documentaries, the camera is less obvious.

![]() Low light: DSLRs can shoot in very low light situations and still maintain their quality.

Low light: DSLRs can shoot in very low light situations and still maintain their quality.

Disadvantages:

![]() Recording time: The current DSLR models have somewhere around a 12-minute maximum continuous recording time. While the camera can be immediately restarted, this does create some recording limitations.

Recording time: The current DSLR models have somewhere around a 12-minute maximum continuous recording time. While the camera can be immediately restarted, this does create some recording limitations.

![]() Audio: DSLRs usually have automatic gain control, unbalanced inputs, and no phantom power. All of these mean that you have to record your audio on a separate high-quality audio device and then sync it later. Another audio disadvantage is that most DSLRs do not include a headphone input to allow you to monitor the audio quality. In order to ensure quality audio, it must be recorded independently and then synced later in postproduction. There are a number of software options available that will assist you in syncing the audio.

Audio: DSLRs usually have automatic gain control, unbalanced inputs, and no phantom power. All of these mean that you have to record your audio on a separate high-quality audio device and then sync it later. Another audio disadvantage is that most DSLRs do not include a headphone input to allow you to monitor the audio quality. In order to ensure quality audio, it must be recorded independently and then synced later in postproduction. There are a number of software options available that will assist you in syncing the audio.

![]() Stability: Due to their small size, DSLRs are handheld, not shoulder mounted. This is not a great design for stability while recording motion. Most camera operators use a shoulder-mounted support when handholding them.

Stability: Due to their small size, DSLRs are handheld, not shoulder mounted. This is not a great design for stability while recording motion. Most camera operators use a shoulder-mounted support when handholding them.

![]() Timecode: The lack of timecode can create some problems when attempting to sync audio in the postproduction process.

Timecode: The lack of timecode can create some problems when attempting to sync audio in the postproduction process.

![]() Quality: In order to obtain the 1080 image from their sensor, some models use a type of line skipping when capturing the image. While this type of down-resing reduces the amount of processing for the camera, it can cause some serious aliasing issues, which causes problems when shooting highly detailed patterns.

Quality: In order to obtain the 1080 image from their sensor, some models use a type of line skipping when capturing the image. While this type of down-resing reduces the amount of processing for the camera, it can cause some serious aliasing issues, which causes problems when shooting highly detailed patterns.

Other DSLR Issues:

![]() The terms used on a still camera are not the same as the terms on a video camera. For example, still cameras use “ISO” while video cameras use “gain.”

The terms used on a still camera are not the same as the terms on a video camera. For example, still cameras use “ISO” while video cameras use “gain.”

![]() There are few video controls on a DSLR compared to a prosumer or professional video camera. This can limit the camera operator’s ability to adjust blacks or other fine-tune adjustments.

There are few video controls on a DSLR compared to a prosumer or professional video camera. This can limit the camera operator’s ability to adjust blacks or other fine-tune adjustments.

![]() The DSLR does not always look professional if you are working for a client. Compared to a typical size professional camera, they may look amateurish.

The DSLR does not always look professional if you are working for a client. Compared to a typical size professional camera, they may look amateurish.

6.4 THE LENS SYSTEM

Engraved on the front of almost every lens are two important numbers:

![]() The lens’s focal length—or in the case of zoom lenses, its range of focal lengths. This gives you a clue to the variations in shot sizes the lens will provide.

The lens’s focal length—or in the case of zoom lenses, its range of focal lengths. This gives you a clue to the variations in shot sizes the lens will provide.

![]() The lens’s largest aperture or f-stop (e.g., f/2)—the smaller this f-stop number, the larger the lens’s maximum aperture, so the better its performance under dim lighting (low-light) conditions.

The lens’s largest aperture or f-stop (e.g., f/2)—the smaller this f-stop number, the larger the lens’s maximum aperture, so the better its performance under dim lighting (low-light) conditions.

There are two fundamental types of lenses on video cameras:

![]() Prime lens (primary lens), which has a specific (unchangeable) focal length. Prime lenses have become specialty items, primarily used by filmmakers, digital filmmakers, and in special use situations such as security or scientific research.

Prime lens (primary lens), which has a specific (unchangeable) focal length. Prime lenses have become specialty items, primarily used by filmmakers, digital filmmakers, and in special use situations such as security or scientific research.

![]() Zoom lens, which has a variable focal length. Zoom lenses are by far the most popular lens on cameras because of their ability to move easily from wide-angle to telephoto focal lengths.

Zoom lens, which has a variable focal length. Zoom lenses are by far the most popular lens on cameras because of their ability to move easily from wide-angle to telephoto focal lengths.

6.5 FOCAL LENGTH AND LENS ANGLE

The term focal length is simply an optical measurement—the distance between the optical center of the lens and the image sensor when you are focused at a great distance, such as infinity. It is generally measured in millimeters (mm).

FIGURE 6.9

Cameras can be white-balanced by filling the viewfinder with the white card held by an assistant. The white-balance button on the camera is pushed and held for a few seconds.

A lens designed to have a long focal length (long focus) behaves as a narrow angle or telephoto system. The subject appears much closer than normal, but you can only see a smaller part of the scene. Depth and distance can look unnaturally compressed in the shot.

When the lens has a short focal length (short focus), this wideangle system takes in correspondingly more of the scene. But now subjects will look much farther away; depth and distance appear exaggerated. The exact coverage of any lens depends on its focal length relative to the size of the camera’s sensor (Figures 6.9, 6.10, and 6.11).

6.6 THE PRIME LENS

The prime lens, which stands for primary lens, is a fixed-focal-length lens (Figures 6.13 and 6.14). Only the iris (diaphragm) within the lens barrel is adjustable. Changing its aperture (f-stop) varies the lens’s image brightness, which controls the picture’s exposure. The focus ring varies the entire lens system’s distance from the receiving camera image sensor.

If a video camera with a single prime lens is being used and a closer or more distant shot of the subject is needed, the camera operator has to move the camera nearer or farther from the subject. The alternative is to have a selection of prime lenses of various focal lengths to choose from.

FIGURE 6.10

A lens designed to have a long focal length behaves as a narrow-angle or telephoto system. When the lens has a short focal length, this wide-angle system takes in correspondingly more of the scene.

FIGURE 6.11

The various shots that can be obtained by different lenses. The wide-angle and telephoto shots can be taken while standing in one place and exchanging lenses.

FIGURE 6.12

This mobile phone app, Artemis, uses the internal video camera to show the various lenses that can be used to shoot a scene. The image can then be saved for future use.

6.7 THE ZOOM LENS

A zoom lens is a variable focal length lens. It allows the camera operator to zoom in and zoom out on a subject without moving the camera forward or backward. The zoom lens enables the camera operator to select any coverage within its range. Most video and television cameras come with optical zoom lenses. An optical zoom uses a lens to magnify the image and send it to the image sensor. The optical zoom retains the original quality of the camera’s sensor (Figure 6.15).

An increasing number of consumer video cameras are fitted with a lens system that combines both an optical zoom and a digital zoom. A camera might, for instance, have a 20X optical zoom and 100X digital zoom. Depending on the quality of its design, the optical zoom system should give a consistently high-quality image throughout its zoom range; the focus and picture clarity should remain optimal at all settings. In a digital system, the impression of zooming in is achieved by progressively reading out a smaller and smaller area of the same digitally constructed picture. Consequently, viewers are likely to see the quality of the image progressively deteriorating as they zoom in because fewer of the original picture’s pixels are being spread across the television screen.

FIGURE 6.13

A prime lens has few features, focus, and aperture.

(Photo courtesy of Zeiss and BandPro.)

Lens design involves many technical compromises, particularly in small systems. The problems with providing high performance from a lightweight, robust unit at a reasonable cost have been challenging for manufacturers. So the optical quality of budget systems is generally below that of an equivalent prime lens.

When the camera operator wants to get a “closer” shot of the subject or is trying to avoid something at the edge of the picture coming into the shot, it is obviously a lot easier to zoom in than to move the camera, particularly when using a tripod. In fact, many people simply stand wherever it is convenient and zoom in or out to vary the size of the shot. However, the focal length of the lens does not just determine the image size. It also affects the following factors:

FIGURE 6.14

A set of prime lenses. This set allows the camera operator to utilize a wide variety of focal lengths.

(Photo courtesy of Zeiss/ BandPro.)

FIGURE 6.15

The zoom lens.

(Photo courtesy of Canon.)

![]() How much of the scene is sharp. The longer the telephoto used, the less amount of depth of field (the distance between the nearest and farthest objects in focus).

How much of the scene is sharp. The longer the telephoto used, the less amount of depth of field (the distance between the nearest and farthest objects in focus).

![]() How prominent the background is in closer shots. The background is magnified at the same time as the foreground subject. Instead of zooming, if the camera were moved closer to the subject, the background size would be different from the zoom shot (see Figure 6.16).

How prominent the background is in closer shots. The background is magnified at the same time as the foreground subject. Instead of zooming, if the camera were moved closer to the subject, the background size would be different from the zoom shot (see Figure 6.16).

![]() How hard it is to focus. The longer the telephoto, the smaller the depth of field.

How hard it is to focus. The longer the telephoto, the smaller the depth of field.

![]() Camera shake. The longer the telephoto, the more the operator’s shake is magnified. The wider the shot, the less amount of shake.

Camera shake. The longer the telephoto, the more the operator’s shake is magnified. The wider the shot, the less amount of shake.

![]() The accuracy of shapes (geometry). Lenses can easily distort shapes. For example, when a very wide-angle lens is tilted up at a tall building, the building will distort, looking as though it is going to fall.

The accuracy of shapes (geometry). Lenses can easily distort shapes. For example, when a very wide-angle lens is tilted up at a tall building, the building will distort, looking as though it is going to fall.

FIGURE 6.16

The background changes in size are due to the lens used. Note that the first photo was shot with a telephoto lens and the last shot was taken with a wide-angle lens. The camera had to be moved closer to the subject for each shot as a wider lens was attached so that the subject would stay the same approximate size.

(Photo by K. Brown.)

As you can see, the zoom lens needs to be used with care, although amateurs do ignore such distortions and varying perspective. The zooming action, too, can be overused, producing distracting and amateurish effects.

6.8 ZOOM LENS REMOTE CONTROLS

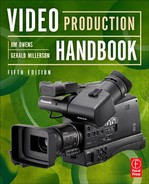

Zoom lens remote controls are an important tool for camera operators. Standing close to the camera to manipulate the controls on the lens is uncomfortable if required for a long period of time. Remote controls allow the camera operator to adjust the focus and focal length of a zoom lens while standing at the back of the camera (Figure 6.17).

FIGURE 6.17

The remote focus and zoom controls allow the operator to manage the lens while working behind the camera. Note in photo (B) that the control cables fit directly into the lens. When the camera is fitted to a camera mount, it is not really convenient for the camera operator to reach around to the front of the camera to adjust the lens. The lens focus and zoom can be adjusted from remote controls attached to the pan bars located at the back of the camera.

6.9 THE APERTURE OF THE CAMERA

When the aperture (size of the opening) is fully opened (probably around f/1.4), it lets the most light into the camera. Its minimum opening, when “stopped down” (under very bright lighting), may be f/22. Remember, the smaller the opening, the bigger the number. Some irises can be stopped down until the picture fades out altogether.

When a camera operator alters the aperture of the lens, two things happen simultaneously:

![]() The aperture changes the brightness of the lens image falling onto the chip, altering the picture’s exposure (Figure 6.18).

The aperture changes the brightness of the lens image falling onto the chip, altering the picture’s exposure (Figure 6.18).

![]() The aperture modifies the depth of field, affecting the sharpness of anything nearer and farther than the actual focused distance (Figures 6.19 and 6.20).

The aperture modifies the depth of field, affecting the sharpness of anything nearer and farther than the actual focused distance (Figures 6.19 and 6.20).

FIGURE 6.18

The lens aperture is adjustable in this illustration from a maximum of f/2 to a minimum of f/16. The larger the aperture (opening), the smaller the f-number (such as f/2) and the shallower the depth of field. Less light is needed in this situation. The smaller the lens aperture, the larger the f-number (such as f/16) and the larger the depth of field. More light is needed to shoot at higher-number f-stops.

FIGURE 6.19

By adjusting the aperture (f-stop), the camera operator can increase or decrease the depth of field. The larger the f-stop number, the larger the depth of field.

You have three options when selecting the lens aperture:

![]() Choose an f-stop to suit the exposure. Adjust the lens aperture to give a properly exposed picture so that you can see tonal gradation and details clearly in the subject. If there is insufficient light, you may need to add additional lighting. If there is too much light, so that the shot is overexposed, the lighting on the subject may need to be reduced, reduce the lens aperture (stop down) or add a neutral-density filter.

Choose an f-stop to suit the exposure. Adjust the lens aperture to give a properly exposed picture so that you can see tonal gradation and details clearly in the subject. If there is insufficient light, you may need to add additional lighting. If there is too much light, so that the shot is overexposed, the lighting on the subject may need to be reduced, reduce the lens aperture (stop down) or add a neutral-density filter.

![]() Choose an f-stop that gives a specific depth of field. People usually concentrate on getting the exposure right and accept whatever depth of field results. However, there will be times, especially in close-up shots, when it is not possible to get the entire subject in sharp focus; in other words, there is insufficient depth of field. Then it is necessary to reduce the aperture and increase the amount of light going into the camera until the exposure is right. The camera operator may want a shallow depth of field so that only the subject itself is sharply defined. Or deep focus can be used, in which everything in shot appears clear-cut.

Choose an f-stop that gives a specific depth of field. People usually concentrate on getting the exposure right and accept whatever depth of field results. However, there will be times, especially in close-up shots, when it is not possible to get the entire subject in sharp focus; in other words, there is insufficient depth of field. Then it is necessary to reduce the aperture and increase the amount of light going into the camera until the exposure is right. The camera operator may want a shallow depth of field so that only the subject itself is sharply defined. Or deep focus can be used, in which everything in shot appears clear-cut.

![]() Settle on an f-stop that averages the lighting situation. There may be times when the camera operator has little or no control over the amount of light on the scene or when the camera needs to move around under varying light conditions. In these situations, there may be little choice but to adjust the lens aperture manually for the best average exposure or to switch on the camera’s automatic iris control and accept whatever depth of field results.

Settle on an f-stop that averages the lighting situation. There may be times when the camera operator has little or no control over the amount of light on the scene or when the camera needs to move around under varying light conditions. In these situations, there may be little choice but to adjust the lens aperture manually for the best average exposure or to switch on the camera’s automatic iris control and accept whatever depth of field results.

FIGURE 6.20

This screenshot is from an app called pCAM. The software helps the director or cameraperson calculate the correct lens, depth of field, and settings.

(Photo by David Eubank.)

6.10 LENS ACCESSORIES

There are three sometimes neglected accessories that fit onto the lens: the lens cap, the UV filter, and the lens hood:

![]() Lens cap. When the camera is not actually being used, get into the habit of attaching the lens cap. This protective plastic cover clips onto the front of the lens and keeps grime from accumulating on the front surface of the protection filter (UV) or the lens surface. The lens surface has a special bluish coating, which improves picture contrast and tonal gradation by reducing the internal reflections that cause “lens flares” or overall graying. Careless cleaning or scratching (from blown sand, grit, etc.) can easily damage this thin film. The lens cap not only prevents anything from scratching or rubbing against the lens surface, but it helps to keep out grit or moisture.

Lens cap. When the camera is not actually being used, get into the habit of attaching the lens cap. This protective plastic cover clips onto the front of the lens and keeps grime from accumulating on the front surface of the protection filter (UV) or the lens surface. The lens surface has a special bluish coating, which improves picture contrast and tonal gradation by reducing the internal reflections that cause “lens flares” or overall graying. Careless cleaning or scratching (from blown sand, grit, etc.) can easily damage this thin film. The lens cap not only prevents anything from scratching or rubbing against the lens surface, but it helps to keep out grit or moisture.

![]() The clear or UV filter. A clear filter is usually kept on the front of the lens to protect the front lens element from damage. See the preceding lens cap section for a description of some of the issues that can arise with lens coatings.

The clear or UV filter. A clear filter is usually kept on the front of the lens to protect the front lens element from damage. See the preceding lens cap section for a description of some of the issues that can arise with lens coatings.

![]() The lens hood (sun shade). This is a cylindrical or conical shield fitted around the end of the lens. When there is a strong light source just out of shot ahead of the camera, it shields off stray light rays that could otherwise interreflect within internal lens elements. Although special lens coatings considerably reduce these lens flares, the lens hood helps to avoid the spurious effects of light, mottling, or overall veiling that could otherwise develop.

The lens hood (sun shade). This is a cylindrical or conical shield fitted around the end of the lens. When there is a strong light source just out of shot ahead of the camera, it shields off stray light rays that could otherwise interreflect within internal lens elements. Although special lens coatings considerably reduce these lens flares, the lens hood helps to avoid the spurious effects of light, mottling, or overall veiling that could otherwise develop.

6.11 THE IMAGE SENSOR

The type of image sensor in a camera greatly affects the quality of the image in its resolution (definition), picture defects, and limitations.

There are several types and sizes of image sensors. These chips typically include hundreds of thousands of tiny independent Cells (called pixels or elements). Each cell develops an electrical charge according to the strength of the light that falls on it. The result is an overall pattern of electrical charges that corresponds to the light and shade in the lens image.

There are significant advantages and disadvantages to these different sensors. The quarter-inch sensors are inexpensive but generally are in focus from close-up to infinity. That means the camera operator has limited creative ability because everything is in focus. The larger the chips, the more ability the camera operator has to selectively focus on the subjects, isolating some with a shallow depth of field while using wide focus in other situations. Of course, the largest sensors are also more expensive and are found in the most expensive cameras.

6.12 SENSITIVITY

All camera systems must have a certain amount of light to produce good, clear pictures. How much will depend on camera design and adjustment and on how light or dark the surroundings are. However, what if the surroundings are not bright enough for you to get good images? You have two options. You must either adjust the camera or improve the lighting.

The simplest solution is to open up the lens aperture to let more of the available light through to the image sensor, up to the maximum lens-stop available (e.g., f/1.4). But then the depth of the field becomes shallower, which may make focusing difficult for close-up shots.

Another possible solution where there is insufficient light is to increase the video gain (video amplification) in the camera. Although the image sensor itself still lacks light, this electronic boost will strengthen the picture signal. Most cameras include two or three manual positions, and some have an automatic gain. A 6-dB increase will double the gain, and a 12-dB increase will quadruple it. A 6-dB boost would give you acceptable quality images in low light levels. A high gain of 12 dB would allow you to obtain a recognizable image, but the quality of the image may be poor. It is best to keep gain to a minimum wherever possible because it increases picture noise (grain) and the picture sharpness deteriorates. However, there will be times when high image technical quality is less important than getting the right shot (Figure 6.21).

FIGURE 6.21

Camera operators often need to shoot in low light (A). One way to increase the detail is to increase the video gain. However, the more the gain is adjusted, the more the image deteriorates in quality (B).

6.13 THE VIEWFINDER

There are basically three types of viewfinders for cameras: an ENG/EFP viewfinder, a studio viewfinder, and a swing-out LCD screen.

Camcorders generally use the ENG/EFP viewfinder. This viewfinder contains a small television (typically 1.5 inches in diameter) with a magnifying lens that enlarges the image to be viewed by the camera operator. With its flexible cup eyepiece held up against one eye, all ambient light is shielded from its picture so that the camera operator cannot only compose the shot but also gets a good idea of exposure and relative tonal values. Some camera designs will allow the camera operator to reposition the eyepiece onto whichever side of the camera is more convenient. It may also angle up and down (or swivel) so that the camera operator can still see the image when using the camera above or below eye level (Figure 6.22).

When the camera is working from a fixed viewpoint or mounted on a dolly, it is possible to use a larger viewfinder. This larger monitor is easier to watch for sustained periods, compared with an eyepiece continually held up to the eye.

FIGURE 6.22

This camera operator is using the ENG viewfinder to view the image.

FIGURE 6.23

The camera operator is using a studio viewfinder on his remote camera. Note that he has taped cardboard onto the visor to reduce the amount of sunlight falling on the monitor.

(Photo by Shannon Mizell.)

Focusing can also be more precise than when watching a small image. A hooded visor is usually fitted around the monitor screen to shield stray light from falling on its picture. This type of viewfinder may be either black and white (monochromatic) or color (Figure 6.23).

![]() LCD swing-out viewfinder. An increasing number of video cameras are fitted with a foldout rectangular LCD screen (liquid crystal display), which is typically 2.5 to 3.5 inches wide and shows the shot in color. It is lightweight and conveniently folds flat against the camera body when out of use. However, stray light falling onto the screen can degrade its image, making it more difficult for the camera operator to focus and to judge picture quality (Figure 6.24).

LCD swing-out viewfinder. An increasing number of video cameras are fitted with a foldout rectangular LCD screen (liquid crystal display), which is typically 2.5 to 3.5 inches wide and shows the shot in color. It is lightweight and conveniently folds flat against the camera body when out of use. However, stray light falling onto the screen can degrade its image, making it more difficult for the camera operator to focus and to judge picture quality (Figure 6.24).

Like all television monitors, viewfinders have brightness, contrast, and focus (sharpness) adjustments. Some of the newer viewfinders have a setting that assists the camera operator in focusing (called focus assist). Remember, viewfinder adjustments do not affect the camera’s video image in any way.

The viewfinder on a camcorder not only shows the video image being shot, but it can also be switched so that the camera operator sees a replay of the newly shot images. Camera operators can check for any faults in camerawork, performance, or continuity and can then reshoot the sequence if necessary.

6.14 INDICATORS

Even if the camera is set in a completely automatic mode (full auto), the camera operator will still need information from time to time about basics such as how much of the recording media is left and the charge level of the batteries. Video cameras carry a range of indicators that give a variety of information and warnings: small meters, liquid crystal panels, indicator lights, and switch markings. Most of the indicators are on the body of the camera, but because the camera operator’s attention is concentrated on the viewfinder much of the time while shooting, several indicators are arranged within the viewfinder. Table 6.2 presents a selection of typical indicators. Keep in mind that no camera has them all.

FIGURE 6.24

This professional camera includes a flip-out LCD screen as well as an ENG/EFP viewfinder.

(Photo courtesy of JVC.)

Table 6.2 Common Camera Indicators

Indicators of various kinds, including the following, are fitted to video cameras.

| Auto-focusing zone selected | Shows whether auto-focus is controlled by a small central area of the shot or the nearest subject in the scene |

| Back light exposure correction | System that opens the lens an arbitrary stop or so to improve exposure against bright backgrounds |

| Gain | Amount of video amplification (gain) being used |

| End of tape warning | Shows the number of minutes remaining on the tape |

| Full auto-indicator | Shows that camera is in fully automatic mode (auto-iris, auto-focus, etc.) |

| Low light level warning | Insufficient light falling onto image sensor, causing underexposure |

| Manual aperture setting | Shows lens iris is in the manual mode |

| Shutter speed | Indicates which shutter speed has been chosen |

| Tally light (cue light) | A red light showing that the camera is recording or, when used in a multicamera setup, shows that the camera is “on-air” |

| Time indicator | Shows running time (elapsed time/tape time used) or the amount of time remaining on the record device |

| Video/audio recording | Indicates that the recorder is recording (audio and video) |

6.15 AUDIO

Most portable video cameras include a microphone intended for environmental (natural) sound pickup (Figure 6.25). It may be built in or removable. A foam sponge cover over the mic reduces low-pitched wind rumble.

FIGURE 6.25

Microphones attached to the camera are generally used to pick up environmental sounds.

To position the microphone more effectively, it is sometimes attached to a short telescopic “boom,” which can be extended to reach out in front of the camera. The use of this type of microphone generally requires the use of a boom operator (Figure 6.26).

An audio monitor earphone/headphone jack enables the camera operator or audio person to monitor the microphone sound pickup during the recording. Audio needs to be assessed continually for quality, balance, background, and other factors. Often background noises that seemed low to the ear during the recording prove obtrusive on the soundtrack. You also can use the earpiece to listen to a replay of the video soundtrack.

An external mic socket on the camera is generally included to plug in a separate microphone for better sound quality and more accurate mic positioning.

An audio input socket may be included to allow a second sound source (such as music or effects) to be recorded on a separate track during the video recording.

During a multicamera production, cameras are connected by an intercom, which allows the camera operator to speak with the director and anyone utilizing the camera operator’s channel. The intercom is usually connected using the camera control unit (CCU).

6.16 POWER

Video cameras normally require a low-voltage direct current DC power supply. This power generally comes from an on-camera battery (which is DC) or an alternating current (AC) adapter that converts AC to DC. Camera operators generally carry multiple camera batteries. There are other power options, including battery belts and special power supplies.

When using batteries, there are a number of precautions you should take to avoid being left without power at a critical moment. The most obvious is to either switch the equipment off when it is not actually being used or switch the camera to a standby (warmup) mode so that it is only using minimum power.

Remember, the camera system (including its viewfinder), the video recorder, any picture monitor you may be using, an audio recorder, and lights attached to the camera are all drawing current. When setting up shots, organizing action, shooting, doing retakes, reviewing the recording, and writing notes, it is easy to squander valuable battery power. Fully charged standby batteries are a must (Figure 6.27).

FIGURE 6.26

A microphone on a “boom” pole is often used to get the mic physically closer to the talent (presenter).

CONTROLLING THE CAMERA

6.17 HANDLING THE CAMERA

Pictures that are shaky, bounce around, or lean to one side are a pain to watch. So it is worth that extra care to make sure that camera shots are steady and carefully controlled. There may be times when the audience’s attention is so riveted to exciting action on the screen that they are unconcerned if the picture does weave from side to side or move about. But don’t rely on it! Particularly when there is little movement in the shot, an unsteady picture can be distracting and irritating to watch. As a general rule, the camera should be held perfectly still, mounted to a camera support, unless the camera operator is deliberately panning it (turning it to one side) or tilting it (pointing it up or down) for a good reason.

FIGURE 6.27

The large battery pack attached to the back of this camera will provide hours of power.

(Photo courtesy of JVC.)

So what stops us from holding the camera steady? There are a number of difficulties. Even “lightweight” cameras grow heavier with time. Muscles tire. Body movements (breathing, heartbeat) can cause camera movement. Wind can buffet the camera. The camera operator may be shooting from an unsteady position, such as a moving car or a rocking boat. On top of all that, if a telephoto lens is being used, any sort of camera shake will be considerably exaggerated. To overcome or reduce this problem and provide a stable base for the camera, several methods of camera support have been developed (Figure 6.28).

FIGURE 6.28

Keeping the handheld camera steady takes practice. Here are some techniques to handhold a camera: (A) Rest your back against a wall. (B) Bracing the legs apart provides a better foundation for the camera. (C) Kneel, with an elbow resting on one leg. (D) Rest your body against a post. (E) Lean the camera against something solid. (F) Lean your side against a wall. (G) Sit down, with your elbows on your knees. (H) Rest your elbows on a low wall, fence, railings, car, or some other stationary object. (I) Rest your elbows on the ground.

(Photos by Josh Taber.)

6.18 SUPPORTING THE CAMERA

There are three basic ways to support a camera:

![]() Use the camera operator’s body. With practice, cameras can be handheld successfully. Depending on the camera’s design, a handheld camera may be steadied against the camera operator’s head or shoulder while he or she looks through the viewfinder eyepiece.

Use the camera operator’s body. With practice, cameras can be handheld successfully. Depending on the camera’s design, a handheld camera may be steadied against the camera operator’s head or shoulder while he or she looks through the viewfinder eyepiece.

![]() Use some type of body support. A number of body supports are available for cameras of different sizes. They add a mechanical support of some type to give the camera added stability (see Figure 6.29).

Use some type of body support. A number of body supports are available for cameras of different sizes. They add a mechanical support of some type to give the camera added stability (see Figure 6.29).

![]() Attach it to a camera mount. The camera can be attached to a camera mount of some type (monopod, tripod) with a screw socket in its base. A quick-release plate may be fastened to the bottom of the camera, allowing it to be removed in a moment.

Attach it to a camera mount. The camera can be attached to a camera mount of some type (monopod, tripod) with a screw socket in its base. A quick-release plate may be fastened to the bottom of the camera, allowing it to be removed in a moment.

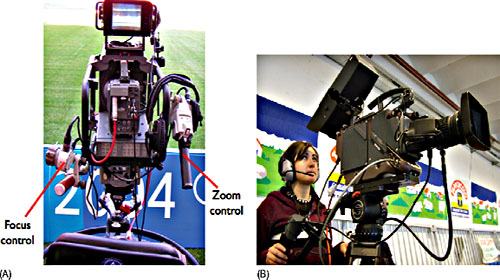

6.19 HANDHELD CAMERAS

When the decision is made to have the operator hold the camera by hand, it is usually because the camera has to be mobile, able to change positions quickly. This method is most commonly used by news crews, for documentaries, at sports events, or for shooting music videos. In all of these situations, the camera generally needs to move around to follow the action (Figure 6.30).

Some of the more lightweight consumer and lower-end professional cameras can be held in one hand. They are not large enough to be shoulder mounted. A camera operator can maintain steadiness fairly easily for short periods of time. However, over longer periods, even lightweight cameras can become difficult to hold steady.

Larger cameras are designed to be shoulder mounted. The body of the camera rests on the camera operator’s right shoulder. The operator places his or her right hand through a support loop on the side of the lens. This way, the operator’s fingers are free to control the zoom rocker (servo zoom) switch while the thumb presses the record/pause switch. The camera operator’s left hand adjusts the manual zoom ring, the focusing ring, and the lens aperture (Figure 6.31).

FIGURE 6.29

A body brace helps to firmly support the camera.

(Photo courtesy of Videosmith.)

The secret to good camera control with a handheld camera is to adopt a comfortable, well-balanced position, with legs apart and slightly bent and elbows tucked in on the sides. Grip the camera firmly but not too tightly, or your muscles will tire and cause camera shake. Enhance steadiness by resting your elbows against your body or something really secure. This may be a wall, a fence, or perhaps a nearby car (see Figure 6.28).

The comfort and success of handholding a camera depends largely on the camera operator’s stamina and how long he or she will be using the camera. Standing with upraised arms supporting a shoulder-mounted camera can be very tiring, so several body braces and shoulder harnesses are available that help the camera operator to keep the camera steady when shooting for long periods (Figure 6.29).

FIGURE 6.30

Handholding a camera for a long period of time will generally produce unsteady shots.

(Photo by Paul Dupree.)

FIGURE 6.31

(A) The shoulder-mounted handheld camera is steadied by the right hand, positioned through the strap on the zoom lens.

(B) That same right hand also operates the record button and the zoom rocker (servo zoom) switch.

(Photos by Josh Taber and Sony.)

6.20 THE MONOPOD

The monopod is an easily carried, lightweight mounting. It consists of a collapsible metal tube of adjustable length that screws to the camera base. This extendable tube can be set to any convenient length. Braced against a knee, foot, or leg, the monopod can provide a firm support for the camera, yet allow the operator to move it around rapidly for a new viewpoint. Its main disadvantage is that it is easy to accidentally lean the camera sideways and get sloping horizons. And, of course, the monopod is not self-supporting (Figure 6.32).

6.21 THE PAN HEAD (PANNING HEAD OR TRIPOD HEAD)

If the camera were mounted straight onto any mount, it would be rigid, unable to move around to follow the action. Instead, it is better to use a tripod head. Not only does this enable the camera operator to swivel the camera from side to side (pan) and tilt it up and down, but the freedom of movement (friction, drag) can be adjusted as well. The tripod head can also lock in either or both directions (Figure 6.33).

FIGURE 6.32

The monopod.

(Photo courtesy of Manfrotto.)

FIGURE 6.33

The gray tripod head (pan head) allows the camera to pan and tilt.

(Photo by Taylor Vinson.)

Although a camera can be controlled by holding it, it is usually much easier to control the pans, tilts, zooms, and focus by using the tripod arms (also known as a pan bar or panning handles) attached to the head.

Whenever the camera is tilted or panned, the camera operator needs to feel a certain amount of resistance to control it properly. If there is too little resistance, the camera operator is likely to overshoot the camera move at the end of a pan or tilt. It will also be difficult to follow the action accurately. On the other hand, if the camera operator needs to exert too much effort, panning will be bumpy and erratic. So the friction (drag) for both pan and tilt is generally adjustable.

Tripod heads for video cameras usually use either friction or fluid to dampen movements. The cheaper, simpler friction head has disadvantages: As pressure is gradually exerted to start a pan, the head may suddenly move with a jerk. And at the end of a slow pan, it can stick unexpectedly. With a fluid head, though, all movements should be steady and controlled.

Locking controls are part of the tripod head. These controls prevent the head from panning or tilting. Whenever the camera is left unattended, it should be locked off. Otherwise, the camera may suddenly tilt and not only jolt its delicate mechanism but even tip the tripod over. Locking controls are useful when the camera needs to be very steady (such as when shooting with a long telephoto lens).

6.22 USING A TRIPOD

A tripod offers a compact, convenient method of holding a camera steady, provided it is used properly. It has three legs of independently adjustable length that are spread apart to provide a stable base for the camera (Figure 6.34). However, tripods are certainly not foolproof. In fact, precautions need to be taken in order to avoid possible disaster, so here are some useful tips:

![]() Ideally, the tripod should be set up before the camera is attached to make sure that it is stable.

Ideally, the tripod should be set up before the camera is attached to make sure that it is stable.

![]() Don’t leave the camera on its tripod unattended, particularly if people or animals are likely to knock against or trip over it. Take special care whenever the ground is slippery, sloping, or soft.

Don’t leave the camera on its tripod unattended, particularly if people or animals are likely to knock against or trip over it. Take special care whenever the ground is slippery, sloping, or soft.

![]() To prevent the feet from slipping, tripods normally have either rubber pads for smooth ground or spikes (screw-out or retractable) for rough surfaces. (Be sure, though, not to use spikes when they are likely to damage the floor surface.)

To prevent the feet from slipping, tripods normally have either rubber pads for smooth ground or spikes (screw-out or retractable) for rough surfaces. (Be sure, though, not to use spikes when they are likely to damage the floor surface.)

![]() If the ground is uneven, such as on rocks or a staircase, the tripod legs can be adjusted to different lengths so that the camera itself remains level when panned around. Otherwise horizontals will tilt as the camera pans. Many tripods are fitted with bubble levels to help level the camera.

If the ground is uneven, such as on rocks or a staircase, the tripod legs can be adjusted to different lengths so that the camera itself remains level when panned around. Otherwise horizontals will tilt as the camera pans. Many tripods are fitted with bubble levels to help level the camera.

![]() Tripods fitted with a camera tend to be top-heavy, so always make sure that the tripod’s legs are fully spread and that it is resting on a firm surface.

Tripods fitted with a camera tend to be top-heavy, so always make sure that the tripod’s legs are fully spread and that it is resting on a firm surface.

![]() There are several techniques for improving a tripod’s stability. The simplest is to add a central weight, such as a sandbag, hung by rope or chain beneath the tripod’s center. The legs can be tied to spikes in the ground. Or use a folding device known as a “spreader” to provide a portable base (Figure 6.35).

There are several techniques for improving a tripod’s stability. The simplest is to add a central weight, such as a sandbag, hung by rope or chain beneath the tripod’s center. The legs can be tied to spikes in the ground. Or use a folding device known as a “spreader” to provide a portable base (Figure 6.35).

FIGURE 6.34

A tripod is a simple three-legged stand with independently extendable legs that can be set up on rough, uneven ground.

(Photo by Paul Dupree.)

6.23 THE ROLLING TRIPOD/ TRIPOD DOLLY

One practical disadvantage of the tripod is that the camera operator cannot move it around while shooting. However, tripods can use a tripod dolly, a set of wheels that fit directly on the tripod, or a wheeled base (called a camera dolly) to become a rolling tripod.

Although it sounds obvious, before moving a rolling dolly, remember to check that there is no cable or obstruction in the camera’s path. It sometimes helps to give a slight push to align the casters in the appropriate direction before the dolly begins. Otherwise the video image may bump a little as the tripod starts to move.

Although widely used in smaller studios, the rolling tripod dolly does not lend itself to subtle camerawork. Camera moves tend to be approximate. Camera height is adjusted by resetting the heights of the tripod legs. So height changes while shooting are not practical unless a jib is attached to the dolly (Figure 6.36).

FIGURE 6.35

The tripod uses a “spreader” to give more stabilization. Note that the camera operator also moved the camera low when not in use. This gives the camera a lower center of gravity, making it more difficult to knock it over.

6.24 THE PEDESTAL

For many years, the pedestal (or ped, as it is widely known) has been the all-purpose camera mounting used in TV studios throughout the world. It can support even the heaviest studio cameras, yet it still allows a range of maneuvers on smooth, level surfaces.

Basically, the pedestal consists of a three-wheeled base supporting a central column of adjustable height. A concentric steering wheel is used to push and steer the mounting around and to alter the camera’s height. Thanks to a compensatory pneumatic, spring, or counterbalance mechanism within the column, its height can be adjusted easily and smoothly, even while on shot. There may be occasions when a second operator’s assistance is needed to help push the pedestal and to look after the camera cable (Figure 6.37).

FIGURE 6.36

A tripod on a dolly. A dolly can operate on a smooth floor or on a dolly track.

(Photo by Will Adams.)

FIGURE 6.37

While primarily used in studios, camera pedestals can also be used outside. Pedestals come in all different sizes, from lightweight to extremely heavy, like the one shown.

6.25 GORILLAPOD

The gorillapod’s flexible, jointed arms allow you to wrap it around a railing, twist it around a tree branch, or loop it onto a shopping cart. This type of camera support is extremely light and easy to travel with, as well as providing great camera support (Figure 6.38).

6.26 BEANBAG

Beanbag camera supports allow the camera to be positioned in all types of angles while holding the camera steady. This type of support is very light and flexible. There are many different brands available (Figures 6.39).

FIGURE 6.38

A Gorillapod’s legs can be twisted around to hold a camera securely in place.

(Photo courtesy of Joby.)

6.27 JIB ARMS

In the golden days of filmed musicals, large camera cranes came into their own: bird’s-eye shots of the action, swooping down to a group, sweeping along at floor level, shots of dancing feet climbing to follow the action as dancers ascended staircases—in the right hands, such camerawork is very impressive (Figure 6.40).

Some television production companies still use small camera cranes (jibs), but they need skilled handling and occupy a lot of floor space compared with a pedestal. If you want a wide variation in camera heights, a much less costly and more convenient mounting is the jib (or jib arm) (Figure 6.41).

The long jib arm (boom) is counterbalanced on a central column. This column is generally supported on a tripod or camera pedestal. The video camera is fixed into a cradle at the far end of the jib, remotely controlled by the camera operator who stands beside the mounting, watching an attached picture monitor. There is a wide range of jib designs, from the lightweight mountings used with smaller cameras with a maximum camera height of 6 feet to heavy-duty jibs that will reach up to 40 feet.

The jib has a variety of operational advantages. It can reach over obstructions that would bring a rolling tripod or pedestal to a halt. It can take level shots of action that occur high above the floor while other mounts working on the floor level can only shoot the subject from a low angle. However, as the jib is swung, the camera always moves in an arc, whether it is being raised, lowered, or turned sideways. It cannot travel parallel with subjects moving across the action area. Whether an operator can turn and raise/lower the jib while on shot and keep the moving subjects in focus and in a well-composed picture will depend on the operator’s skills—and a bit of luck.

FIGURE 6.39

Beanbags can securely hold a camera in place without the need for a tripod.

(Photos courtesy of The Pod and Cinesaddle.)

FIGURE 6.40

This small, relatively inexpensive jib arm fits onto a standard video tripod. It also folds up into a travel case.

FIGURE 6.41

(A) Large jibs require skilled talent. (B) The operator remotely controls the head from the red control box while viewing the image on the attached monitor.

6.28 SPECIALTY CAMERA MOUNTS

Several devices are available that can help camera operators cope with those awkward occasions when the camera needs to be secured in unusual places. Typical equipment that can prove handy for smaller production units include the following:

![]() Camera clamps. Metal brackets or clamps of various designs, which allow the camera to be fastened to a wall, fence, rail, door, or other structure (Figure 6.42).

Camera clamps. Metal brackets or clamps of various designs, which allow the camera to be fastened to a wall, fence, rail, door, or other structure (Figure 6.42).

![]() Car rig (or car mount). A car mount that attaches to the car, inside or outside of the car, in order to capture images that would otherwise be difficult to obtain. Some mounts use suction cups to fit onto the car, others fit over the side door, and some sit in a beanbag-type mount as shown in Figure 6.43.

Car rig (or car mount). A car mount that attaches to the car, inside or outside of the car, in order to capture images that would otherwise be difficult to obtain. Some mounts use suction cups to fit onto the car, others fit over the side door, and some sit in a beanbag-type mount as shown in Figure 6.43.

The Steadicam, Glidecam, and Fig Rig are just some of the special camera stabilizers that take the shake and shudder out of wide camera movements. These systems allow the camera operator to take smooth traveling shots while panning, tilting, walking, running, climbing, and so forth. An LCD color screen (treated to reduce reflections) allows the operator to monitor the shots (Figures 6.44 and 6.45).

FIGURE 6.42

A variety of camera clamps have been designed to mount the camera to almost anything.

(Photo courtesy of Manfrotto.)

FIGURE 6.43

Car mounts can be anything from a “saddlebag” (large beanbag) (A) to a rigid metal brace with suction cups (B). The goal is to make sure the camera is safe while shooting.((A) by Taylor Vincent and (B) courtesy of VFGadgets.)

FIGURE 6.44

Smaller cameras can be supported by a handheld steady device like this Steadicam. However, larger cameras must be steadied by a device that includes a body brace.

(Photo courtesy of Steadicam/Tiffen.)