Accounting for capital investment appraisal

Time for a radical change?

Introduction

The thinking behind accounting for capital investment decisions (CIDs) has not developed greatly since the 1950s when present value tables were created (Bromwich, 1976). An increasingly widespread use of computing generally and spreadsheets specifically in the 1970s made discounted cash flow (DCF) methods the financial tool of choice for most organisations (Haka, 2007, p. 705–706). Critics of this narrow economics-based view of CIDs have preferred to position investment appraisal as part of a wider strategic management activity, where non-financial considerations and managerial judgement play an equally important part in strategic investment decision-making (SIDM) as the financial analysis (Emmanuel et al., 1990; Harris et al., 2009).

Case study research has highlighted the tendency for multiple managers to participate in CIDs, drawing on a range of heuristics and utilising broad frames of reference when balancing financial and strategic considerations in reaching managerial judgement (Emmanuel et al., 2010). The majority of companies surveyed by Harris et al. (2009, p. 81) reported using a standard set of procedures (e.g. a capital budgeting manual, business plan templates) as well as DCF techniques and risk evaluations. However, these business plans may not deal with stakeholder interests beyond the investor and customer perspectives and there is less evidence of formal multi-attribute criteria being adopted in business than in the public sector (e.g. Srithongrung, 2010; Afful-Dadzie and Afful-Dadzie, 2016).

Another issue with DCF based investment appraisal techniques is that they are seldom applicable in professional services firms (such as accountants and solicitors) or in the increasing number of dot-com businesses. This is largely because many strategic decisions do not involve a significant financial outlay but the investment of time and expertise (human and intellectual capital). Integrated Reporting (IR) represents a new way of thinking about and reporting organisational performance. It recognises six forms of capital, namely manufactured, human, intellectual, social, natural and financial and could herald the biggest change in accounting and Accounting Information Systems (AIS) we have seen in a long time (Busco et al., 2013).

This chapter considers the problems with Accounting Information Systems (AIS) typically used in capital budgeting. We identify issues with the use of spreadsheets for investment appraisal and the lack of formal systems for evaluating or integrating non-financial information. We explore the emergence of integrated reporting and the challenges for AIS to incorporate integrated thinking into strategic investment appraisal. We propose a new meaning for capital investment that incorporates all the capitals, not just the financial capital. Finally, we consider how AIS practice could develop to bring capital investment appraisal techniques up-to-date to tackle modern day decision-making in organisations.

Accounting for capital investment decisions

There are several authors who have charted the historical development of modern capital budgeting. Most, like Callahan and Haka (2004), focus on the economics of capital budgeting (Bromwich, 1976) and go back to the roots of DCF techniques (e.g. Hirshleifer, 1958). Awareness of these techniques and the extent of their use have been captured by surveys of practice. Haka (2007, p. 706–707) summarises 35 such surveys over the period 1959–2002, despite criticism of the survey instruments used to capture CID practice (for example Rappaport, 1979). Haka (2007) also charts 17 examples of modelling based research, 19 experimental studies and 21 organisational and institutional-based studies, leading to a more rounded view of CID as a process involving a complex network of actors.

For most companies, strategic investment decisions (SID) are mainly distinguished by the size of the projects and the strategic importance of the project opportunity to the company. The SID process is generally broken down into four stages and seven steps (Harris, 1999). The first stage focuses on the identification of potential projects, the outline of the business case and the initial project screening. The second stage focuses on the detailed appraisals of projects. Departmental and senior management will make intermediate and final decisions in the third stage after assessing financial and strategic factors. The final stage focuses on post audit review.

Harris et al. (2009) used a combination of survey and case-based methods to examine the people and process dimensions more closely, developing knowledge of SID practice based on the psychology of managerial judgement (Emmanuel et al., 2010). Harris et al. (2016) examined 18 fieldwork-based studies in general and analysed four case-based studies in more detail, proposing theorisation of SID practice using strong structuration theory from sociology. We have revisited several of those studies and searched for more work that actually focuses on the Accounting Information Systems used in CIDs, but whilst some studies examine the role that accounting plays (for example Huikku and Lukka, 2016), we cannot find any that presents the accounting content. This is probably due to the confidential nature of accounting data to support SIDM and the understandable reluctance of organisations to allow this kind of data to be published.

The lead author has kept examples of business case papers (obtained with permission) from her past research but with no explicit permission to publish the contents, so the evidence is not shown here. A typical project paper in the 1990s would contain a narrative setting out the project definition and fit with the strategic plan, along with the key aspects of the activities involved and the justification for the proposal. This may number some 4–14 pages, depending on the size of the project, and have a financial analysis appended, usually 1–3 pages of spreadsheet output and for some projects a 2–3 page risk analysis would also be appended. Hence the financial analysis element may only account for 15–20% of the document. It was clear that the finance professionals in the organisation provided the financial analysis and there was seldom a clear integration of the narrative and the numbers. However, it was the headline financial data that appeared on the front sheet for the group board’s consideration. This data would have been derived from the spreadsheet output.

Spreadsheets used in accounting for decision-making

The spreadsheet is the most commonly used tool for the appraisal and decision stages in SIDs. However, the spreadsheet itself has weaknesses in three areas: (1) the spreadsheet is an end-user tool and errors can be prevalent (Powell et al., 2009a, 2009b), (2) a spreadsheet can perform standard financial appraisal well but it falls short on the appraisal of non-financial elements, and (3) the spreadsheet has limitations in handling advanced risk assessment. We present a series of examples of spreadsheet functions and formats typically used in SIDs. The examples are not based on real data, but constructed to illustrate our critique.

User-induced errors and bad design practices

User-induced errors are common on spreadsheets, but it could be difficult for other end-users or even auditors to determine whether the anomalies are intentional or not. Panko (2006) summarised the results of seven spreadsheet-related field audits and concluded that 94% of spreadsheets in those audits contained errors. Powell et al. (2009a) studied 50 large-scale operational spreadsheets that came from a wide variety of sources and found errors in 0.9–1.8% of all cells that contained formulas, depending on how errors are defined. Powell et al. (2009a) suggest that their studies have confirmed the general belief that errors in spreadsheets are common and have provided evidence for the hypothesis that around 1% of all formulas in operational spreadsheets are in error.

Another study from Powell et al. (2009b) discovered that although many of the spreadsheet errors have little or no impact on the financial output, spreadsheet practice can range from excellent to poor even when the developers come from the same organisation. There also appears to be little correlation between the importance of the spreadsheet and its quality. Powell et al. (2009a, p. 130) found that “because the spreadsheet platform is so unstructured, and because end-users generally follow unique designs, errors and poor practices can arise in thousands of different guises”.

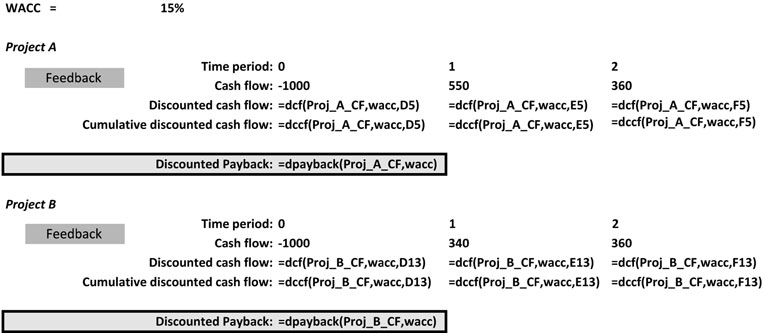

The findings are unsurprising. In the case of project appraisal, spreadsheets are typically prepared by the investing departmental financial managers. The related spreadsheets, even without error, are prepared and maintained by individual end-users. The practices of presentation can be non-standardised, and formulas are usually complicated and may only be understood by original developers (see Figure 14.1 and Figure 14.2). Such a spreadsheet can hardly function as an object of communication to enable or encourage exchange of information and opinions.

Limitation of spreadsheets in capturing non-financial factors

Adler (2000) summarises the major criticisms of traditional financial approaches to SID appraisal as: narrow in perspective, exclusion of nonfinancial benefits, overemphasis of the short term, wrong assumptions of the status quo and promotion of exaggerated potential financial returns. Alkaraan and Northcott’s (2006) survey of large UK manufacturing companies’ CID methods discovered that the four major financial appraisal techniques remain (in order of popularity) NPV, IRR, payback period and accounting rate of return, with 88% of respondents using three or more techniques. While these findings are consistent with previous studies (e.g. Ryan and Ryan, 2002; Arnold and Hatzopoulos, 2000), one of the interesting findings is that they did not detect any significant difference in the priority of appraisal methods being applied among strategic and non-strategic projects. On the one hand, this may indicate that managers are aware of the fact that soft factors and strategic elements are not included in a spreadsheet and they have to make subjective judgements. On the other hand, this may show that there are gaps between the awareness of such factors and the incapability of spreadsheets to capture or to represent them.

Figure 14.1 A typical spreadsheet

It could be difficult for other users to read through the formulae and understand the underlying assumptions for the projection, particularly when there are special assumptions such as an absolute value plugged into the formula for a specific cell.

Figure 14.2 A spreadsheet may have custom functions

Managers can focus on interpretation of the appraisals and provide feedback on the financial analysis.

Traditional financial methods can be narrowly focused on direct financial impact. For example, the SID appraisal process may ignore the financial impact (positive or negative) that can be cascaded through the value chain (Shank and Govindarajan, 1992). Departmental managers may overlook the synergies or frictions that can be generated through the value creation. Spreadsheets are usually close-ended. The outputs of a specific CID/SID spreadsheet are rarely linked to the input of related CID spreadsheets of other departments. Aggregated benefits/impacts cannot be easily observed even by senior management.

Traditional financial methods cannot capture non-financial benefits. The competitive advantages of companies are more and more determined by intellectual capital (IC) investment, namely human capital, organisational capital and relational capital. The measurement of IC involves the identification of the relationship between a company’s intangible resources and its activities, and the development of a list of predominantly non-financial indicators to represent the growth/decline of such resources as well as the efficiency and effectiveness of management activities (Chiucchi, 2013). Most of the measurements of IC are qualitative and narrative.

A typical company-wide IC report (Chiucchi, 2013) may contain 30 to 200 IC indicators and tens of thousands of words in narrative description. For example, intangible benefits such as the “learning experience” that can be passed from one department to another through a new project cannot be captured in financial terms. Another example is the difficulty in determining the financial benefits and terminal value of a modern customer management database from a relational capital perspective. A spreadsheet is a numerical tool. It can capture some qualitative information but it does not enable or enhance extensive sharing of qualitative or textorientated information. Non-financial benefits are always treated as afterthoughts or just quick comments to some specific cells in the spreadsheet (see Figure 14.3). Financial and non-financial considerations in SID process are not well integrated in spreadsheets.

Limitation of spreadsheets in strategic analysis and risk assessment

Spreadsheet analysis may encourage short-term biased SID. IRR and NPV methods are supposed to capture the effects of all future returns. Typical sensitivity analyses are focused on using different discount rates, different scenarios of investment outcomes and assigning probabilities for each scenario. While all three parameters are usually submitted by departmental managers, studies show that senior management are more inclined to use a higher discount rate as a buffer (e.g. Drury, 1990; Abdel-Kader and Dugdale, 1998; Kaplan and Atkinson, 2015). Another issue is that managers usually use the same discount rate throughout the lifetime of the projects, which is inappropriate as uncertainty of the project will be reduced after the initial periods. The reliance of using higher and flat hurdle rates as investment decision rules will inevitably cause the SID projects to be short-term driven. Spreadsheets for SIDs are typically project specific and are not linked with historical data (although they can be if the IT department can create custom data retrieval functions). If post-investment audit results cannot be retrieved on an ad hoc basis, senior managers may not be able to perform sensitivity analysis objectively (e.g. realised historical costs of capital or success rates of similar projects).

Figure 14.3 Spreadsheets can add basic comments but they do not encourage active information and opinion sharing

Alkaraan and Northcott’s (2006) survey asked respondents to rank eight different techniques for assessing risks (adjusted payback period, adjusted IRR, adjusted discounted rate, adjusted cash flow, probability analysis, computer simulation, CAPM and scenario analysis). Their study found that scenario analysis, adjusted IRR, probability analysis and shortened payback period are the most commonly used risk assessment techniques. However, respondents only assigned more importance to adjusting payback period, IRR, discount rate and forecast cash flow for SIDs. There was no significant difference detected on using other more advanced risk assessment methods between SIDs and non-SIDs.

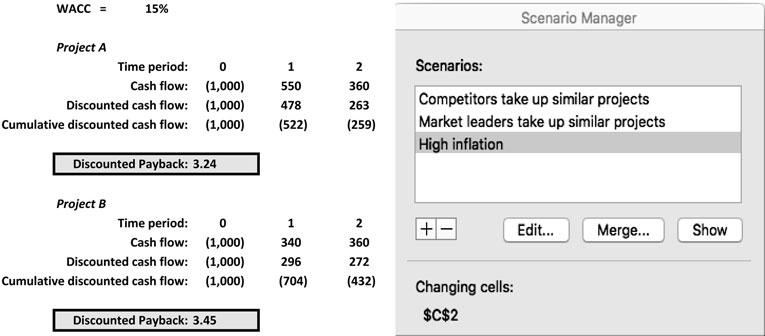

It is not easy for end-users to use spreadsheets to incorporate advanced models for risks. Managers can have faulty assumptions about the status quo and this could become a serious issue for companies that are operating in highly competitive industries (Adler, 2000). If advanced methods are not used, and sensitivity analyses are conducted merely by adjusting parameters that are based on the status quo, cash flow projections may turn out to be too optimistic or may have ignored the opportunity cost of “not doing the project”. In fact, modern spreadsheets are capable of performing basic dynamic scenario analysis and optimisations, but managers (end-users) do not necessarily have the skills to incorporate the appropriate dynamic models into their financial analysis (see Figure 14.4 and Figure 14.5). Other users of spreadsheet also may not have the skills to interpret the more advanced models.

While managers may be aware of the shortfalls of traditional financial appraisal techniques, the spreadsheet is not designed to fill those gaps. Both decision-makers and managers might be overwhelmed by the quantitative information presented by the numbers-focused spreadsheet. This situation may foster a vicious cycle of inflating projections. When spreadsheets cannot appropriately reflect and analyse the intangibles factors and/or are incapable of incorporating advanced risk assessment methods that can be easily understood and used by end-users, decision-makers may simply make a conservative estimate of the financial parameters. If departmental managers perceive the primary decision criteria to be financial, represented by spreadsheet output, with investment risks being assessed simply by inflated discount rates, they may decide to inflate the cash flow (Carr and Tomkins, 1996).

Figure 14.4 Excel has basic optimisation tools, but managers need to have advanced skills to use them

Figure 14.5 Modern spreadsheets have basic scenario management tools but a lack of dynamic models to study the interactions among various parameters

In summary, if managers rely too much on a spreadsheet as the decision tool of investment decisions, the decisions could become misguided. Some issues with spreadsheets relate to the end-user’s practice or their knowledge. Other issues are due to the functional limitations of spreadsheets. The spreadsheet is designed to be a flexible and powerful end-user tool, but advanced application knowledge is usually required if additional functions are needed. For most users, spreadsheets are weakly integrated with historical data and lack dynamic modelling capability. Spreadsheets may encourage the over-reliance on traditional financial analysis (qualitative information and managers’ opinions are rarely included in the spreadsheets). If departmental managers do not have the appropriate setup of business scenarios in their spreadsheet, senior management may be inclined to adopt simple criteria (inflated hurdle rates or arbitrary probability of success). There are also decision related factors that cannot be easily captured by numbers (non-financial returns or financial returns that are hard to be pinpointed), and some strategic analyses that cannot be conducted by standard spreadsheet functions at all (e.g. dynamic analysis of competitors’ responses).

Numbers or narrative?

There are broadly two types of decisions that managers face: recurring decisions, e.g. routine asset replacement to maintain current operations and activities, and strategic decisions that are vital to achieving the organisation’s strategy or taking the organisation in a different direction. The former are the most predictable and accounting for them can make use of existing spreadsheet models to repeat the analysis conducted last time a similar decision was made. These may include new product developments where new products are variants of an existing product. The latter, however, are more often one-off decisions that are by their nature more unpredictable. These include the more innovative new product developments that may radically change the end-user’s experience. This requires at the very least some change to the spreadsheet model to appraise them and may require a completely bespoke form of analysis to evaluate the financial outcomes.

It is argued here that whilst numbers might take precedence in the evaluation of the routine decisions, the level of uncertainty involved in the more strategic decisions makes financial models less meaningful. This is due to the lack of reliable input in terms of the context, risks, assumptions and consequences. No amount of what if analyses or risk adjusted hurdle rates makes the numbers used in the evaluation reliable enough for these strategic decisions to be made based on numbers alone. In extreme cases, the numbers may indeed become so meaningless that managers barely pay any attention to them at all (e.g. Elmassri et al., 2016). This is where the narrative necessarily takes precedence over the numbers. The problem is that there may be less guidance for managers to follow regarding the narrative analysis of the decision.

Professional guidance

The most recent source of professional guidance found on investment appraisal in the UK is contained in a Finance and Management special report (ICAEW, 2009). It outlines the key issues in the “art of investment appraisal” and offers principles of good practice and technical advice on the use of financial analysis techniques. It adds a third basic type of decision to the two mentioned above, which is an obligatory or compliance project imposed by legal or contractual obligations.

Harris (2011, p. 4) offers a more detailed project typology, which classifies IT/systems development and new product development projects as “diamond” projects that “capture the imagination and look attractive in the marketplace”; site or relocation projects, “physical structures, e.g. buildings and roads” as “spades”; business acquisitions and organisational change as “hearts” projects to “engage participants’ hearts and minds”; and compliance and events projects, where there is a “need to work to a fixed schedule of events” as “clubs” in a playing card analogy. The generic and specific strategic level risks attached to these different types of projects are summarised (Harris, 2011, p. 4) drawing from the risk maps presented in Harris et al. (2009). These risk maps add a visual presentation of the conceptualisation of project risk that arguably has more communicative power than any spreadsheet.

ICAEW (2009, p. 10) offers guidance on the content of an appraisal document to support decisions that includes the obvious financial analysis (fixed asset and working capital requirements) and consideration of economic factors such as inflation, interest rates and taxation. It also includes the functional business aspects such as sales and marketing; production and engineering; technology; human resources and management. Most importantly it includes a consideration of alternative projects and the consequences of not proceeding, which so many managers rely upon if the decision cannot be justified by the numbers alone (Elmassri et al., 2016).

The guide (ICAEW, 2009, p. 11) also provides a checklist of items to be considered when appraising an investment proposal for a major new project that adds social and environmental considerations, the proposed timetable and risk assessment to the content guidance above. There is also advice on making key assumptions explicit in the appraisal document and the questioning and challenging of assumptions in the consensus-seeking process is regarded as key to improving managerial judgement in the SID-making process (Harris et al., 2009, p. 46). This would add considerably to the narrative content of the appraisal documents prepared back in the 1990s.

ICAEW (2009, p. 13–14) goes on to provide more specific advice relating to business acquisitions, as the evidence of success in terms of post-acquisition gains for the acquiring firm’s shareholders continues to show (Arnold and Hatzopoulos, 2000) as mentioned above. It seems that these decisions are far more governed by hearts than minds, which is not what is expected of major corporations with specialist data analysts.

ICAEW (2009, p. 26) raises a number of issues for debate in terms of the theory and practice of investment appraisal, which includes the question of how investment appraisal is (or is not) influenced by corporate social responsibility, the danger of the default scenario of “do nothing” being assumed to be resource neutral (ignoring competitor behaviour), environmental and market risk attached to the credit crunch and recession, and globalisation. They also acknowledge the gap between academic and practitioner perceptions, especially in relation to the perceived rarity of practical applications of real options theory.

Further professional guidance is provided by the New York–based International Federation of Accountants (IFAC, 2008) in the form of principles of good practice in investment appraisal, summarised in Table 14.1.

This advice still appears to be very biased towards economic rational analysis, with the possible exception of D which advises a good understanding of the business and strategic imperatives for the proposal, but little advice is offered as to how such matters could best be investigated, analysed or reported.

It seems that both practitioners and academics are aware of some key issues involved in accounting for decision-making in practice, which we summarise here. There are limitations of spreadsheets as the main accounting tool for decisions, whether routine or strategic, as the exercise may become “mechanical” and the numbers may be divorced from the narrative. Groot and Selto (2013, p. 235) summarise the implementation issues as “problems of accurately modelling an investment’s: risk and uncertainty; useful lifetime; the cost of capital; future cash flows”. Whilst they recommend ways of dealing with these problems within the spreadsheet analysis and show how decision trees can help to present the models used, the focus is still very much on calculating the impact on financial capital. Risk in a business sense and other non-financial factors are difficult to integrate into the analysis. Professional guidance acknowledges some of these issues, but has so far fallen short of recommending substantially new ways of accounting for strategic decisions. In the next section, we explore the potential for integrated reporting, and more specifically integrated thinking to offer a new way forward to address these concerns.

Table 14.1 Principles of good practice in investment appraisal

A. |

When appraising multi-period investments, where expected cash flows arise over time, the time value of money should be taken into account. |

B. |

The time value of money should be represented by the opportunity cost of capital. |

C. |

The discount rate used to calculate the NPV in the DCF analysis should properly reflect the systematic risk attributable to the project, not the [whole] organisation. |

D. |

A good decision relies on an understanding of the business and an appropriate DCF methodology. DCF analysis should be considered and interpreted in relation to an organisation’s strategy and its economic and competitive position. |

E. |

Cash flows should be estimated incrementally. |

F. |

At any decision-making point, past events and expenditures should be considered irreversible outflows that should be ignored. |

G. |

All assumptions in DCF analysis should be supported by reasoned judgement, particularly where factors are difficult to predict and estimate. |

H. |

A post-completion audit of an investment decision should include an assessment of the decision-making process, the results, benefits and outcomes of the decision. |

Source: IFAC, 2008

The emergence of integrated reporting and integrated thinking

In 2010, the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) was formed. This was a direct response to calls from the corporate governance movement for better integration of financial and non-financial (especially sustainability issues) information in the reporting of company performance (Dumay et al., 2016). Integrated reporting (IR) may be seen as a new style of corporate reporting that acknowledges multi-capitalism. In this section, we consider the principles of IR and the thinking behind it.

The principles of IR

The IIRC published the integrated reporting framework in 2013 to guide the production and content of a new style of company report (IIRC, 2013) to tell the company’s value creation story. The eight content elements are in Table 14.2.

The main idea of this report is to recognise the wide variation in individual circumstances of different organisations, yet to enable a sufficient degree of comparability across organisations to meet users’ relevant information needs. Thus, the integrated reporting framework does not set out rules for measurement, disclosure of single matters or identify the specific key indicators. Rather, the main driver of this framework is integrated thinking, which the IIRC argues will lead to integrated decision-making and execution towards value creation over the short, medium and long term. Through this integrated thinking, organisations may be stimulated to focus on the connectivity and interdependencies among a range of factors that have a material effect on their ability to create value over time. The guiding principles are in Table 14.3.

So far, the reader could be forgiven for asking what this external reporting framework has to do with the internal business of appraising capital investment projects, apart from the strategic focus and future orientation principle and the call to report how a company allocates resources to achieve its goals. However, it is the resources that are framed as forms of capitals that we are primarily interested in here. The six capitals identified by the IRC framework are financial; manufactured; human; intellectual; social/relationship; and natural capital.

Table 14.2 Integrated reporting framework

Organisational overview and external environment: What does the organisation do and what are the circumstances under which it operates? |

Governance: How does the organisation’s governance structure support its ability to create value in the short, medium and long term? |

Business model: What is the organisation’s business model? |

Risks and opportunities: What are the specific risks and opportunities that affect the organisation’s ability to create value over the short, medium and long term, and how is the organisation dealing with them? |

Strategy and resource allocation: Where does the organisation want to go and how does it intend to get there? |

Performance: To what extent has the organisation achieved its strategic objectives for the period and what are its outcomes in terms of effects on the capitals? |

Outlook: What challenges and uncertainties is the organisation likely to encounter in pursuing its strategy, and what are the potential implications for its business model and future performance? |

Basis of presentation: How does the organisation determine what matters to include in the integrated report and how are such matters quantified or evaluated? |

Source: IIRC, 2013, p. 5.

Table 14.3 The principles of IR

Strategic focus and future orientation: An integrated report should provide insight into the organisation’s strategy, and how it relates to the organisation’s ability to create value in the short, medium and long term and to its use of and effects on the capitals. |

Connectivity of information: An integrated report should show a holistic picture of the combination, interrelatedness and dependencies between the factors that affect the organisation’s ability to create value over time. |

Stakeholder relationships: An integrated report should provide insight into the nature and quality of the organisation’s relationships with its key stakeholders, including how and to what extent the organisation understands, takes into account and responds to their legitimate needs and interests. |

Materiality: An integrated report should disclose information about matters that substantively affect the organisation’s ability to create value over the short, medium and long term. |

Conciseness: An integrated report should be concise. |

Reliability and completeness: An integrated report should include all material matters, both positive and negative, in a balanced way and without material error. |

Consistency and comparability: The information in an integrated report should be presented on a basis that is consistent over time and in a way that enables comparison with other organisations to the extent it is material to the organisation’s own ability to create value over time. |

Source: IIRC, 2013, p. 5.

These capitals are stores of value that, in one form or another, become inputs to the organisation’s business model. They are increased, decreased or transformed through the activities of the organisation in that they are enhanced, consumed, modified or otherwise affected by those activities. For example, an organisation’s financial capital is increased when it makes a profit and its human capital is increased when employees become better trained. The six categories of capital identified by the IIRC may be the key to developing a different style of capital investment appraisal. Together, these capitals are the basis of an organisation’s value creation. The IIRC definitions of the six capitals are in Table 14.4 overleaf.

Whilst not all six capitals will be equally relevant to all organisations or of equal importance within an organisation, it is an attempt to go beyond financial capital in a way that could be seen to fit with societies concerns about the “unacceptable face of capitalism” at the same time as addressing the typically advantaged stakeholder group of shareholders. Since IR has been introduced, it has become mandatory in South Africa and IR supporters such as Eccles and Krzus (2010, 2014) and Busco et al. (2013) may expect that IR will embrace the organisation’s sustainability reporting and become the way forward in corporate governance. In the other words, the organisations will report all the capitals which influenced and were influenced by an organisation’s business activities. However, IR also has its critics.

One primary point of weakness of the IR framework is that it includes the influences from the capitals to the organisation, but excludes the organisation’s effects on their capitals, except in some cases where these impacts rebound on the organisation’s business (Flower, 2015). Two examples are given. The manufactured capitals of an organisation also include some physical objects that are essential for the organisation’s operations which do not belong to companies, such as public ports or waterways. If these objects are damaged as a result of company operations, will the organisation’s IR report such damage? In a similar way, human capital values are evaluated through their contribution to the corporate operation or influence on corporate profitability in the future. What happens if a member of staff is injured or killed?; the organisation may incur the cost of paying fines or compensation. In some cases, this excludes people in the community who have been killed or injured, for example by poisoning from water pollution or gas emissions, which resulted from company operations.

Table 14.4 IIRC definitions of the six capitals

Financial capital is defined as “the pool of fund that is: available to an organisation for use in the production of goods or the provision of services; obtained through financing, such as debt, equity or grants, or generated through operations or investments” |

Manufactured capital: Manufactured physical objects (as distinct from natural physical objects) that are available to an organisation for use in the production of goods or the provision of services: • buildings • equipment • infrastructure (such as roads, ports, bridges and waste and water treatment plants) |

Manufactured capital is often created by one or more other organisations, but also includes assets manufactured by the reporting organisation when they are retained for its own use |

Human capital: People’s competencies, capabilities and experience, and their motivations to innovate, including their: • alignment with and support for an organisation’s governance framework and risk-management approach, and ethical values such as recognition of human rights • ability to understand, develop and implement an organisation’s strategy • loyalties and motivations for improving processes, goods and services, including their ability to lead, manage |

Intellectual capital: Organisational, knowledge-based intangibles, including: • intellectual property, such as patents, copyrights, software, rights and licences • “organisational capital” such as tacit knowledge, systems, procedures and protocols • intangibles associated with the brand and reputation that an organisation has developed |

Social and relationship capital: The institutions and relationships established within and between each community, group of stakeholders and other networks (and an ability to share information) to enhance individual and collective well-being. Social and relationship capital includes: • shared norms, and common values and behaviours • key relationships, and the trust and willingness to engage that an organisation has developed and strives to build and protect with customers, suppliers, business partners, and other external stakeholders • an organisation’s social licence to operate |

Natural capital: All renewable and non-renewable environmental stocks that provide goods and services that support the current and future prosperity of an organisation. It includes: • air, water, land, forests and minerals • biodiversity and ecosystem health |

Source: IIRC, 2013, p. 11–12.

There is a long way to go before we see if and when the somewhat idealistic picture of IR portrayed by the IIRC will gain widespread support. This is quite normal for new business frameworks. One only has to look at the criticism Kaplan and Norton’s (1996) balanced scorecard received (Nørreklit, 2000) and still receives (Jakobsen et al., 2010) though it has since become commonplace in the corporate performance management toolkit of organisations worldwide. Could IR be expected to be any different? It has already gained some weighty support from the Big 4 firms and professional bodies (see KPMG, 2015) and the C-group (Chief Executives, Chief Financial Officers, etc.) according to the Chartered Global Management Accountant (CGMA, 2016) survey backed by CIMA. The interesting aspect of the latter report (CGMA, 2016) is the focus upon the integrated thinking underlying IR in making a difference in corporate decision-making.

Integrated thinking

Integrated thinking (ITh) is defined by the IIRC as “an organisation’s active consideration of the relationships between its various operating and functional units and the capitals the organisation uses and affects” (IIRC, 2013, p. 2). In addition, “Integrated thinking leads to integrated decision-making and actions that consider the creation of value over the short, medium and long term” (IIRC, 2013, p. 2) and it also “takes into account the connectivity and interdependencies between the range of factors that affect an organisation’s ability to create value over time” (IIRC, 2013, p. 2). The IIRC therefore advocates ITh as creating more sustainable value.

Any company that wants to start the IR process will need insight into a broader set of information compared with traditional financial analysis. And this information should be more interconnected and more forward-looking (CGMA, 2014). Or, as summed up in the SAICA (2015, p. 5) survey: “Integrated Thinking promotes a more holistic assessment to grow better businesses and better societies”. It is promoted as a way of breaking down internal silos, reducing duplication and driving positive behaviour focused on long-term success. Firms may use ITh to cope with changing business circumstances that often require a disruptive change in strategy.

Churet and Eccles (2014) explain the relationship between ITh and IR using the metaphor of an iceberg, with the integrated report being the top and integrated thinking representing everything below the surface. However, in the current framework/proposal the IIRC (2013) has focused primarily on the feature of a single IR document with guiding principles and content elements rather than broader concepts of why and how integrated thinking should be embedded in an organisation. Thus, organisations need another approach to provide a clear view and systematic procedure model for the analysis of pros and cons as well as improvement activities, for example taking intangible resources into account and putting more emphasis on issues relates to sustainability.

CGMA (2016, p. 6) argues the need to tackle bureaucratic decision-making structures in today’s world, “characterised by volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity” where “strategic decision-making is increasingly critical”. They advocate ITh as having the potential to make decision-making more agile. If there are few studies in the academic literature on IR (Dumay et al., 2016), there are fewer on ITh. The C-group surveyed (CGMA, 2016, p. 17) reported the need for greater trust and collaboration to help ITh.

How can integrated thinking be incorporated into capital investment appraisal

Oliver et al. (2016, p. 228) warn that “potential problems can arise if hard integrated thinking dominates over the soft, and data required for internal management accounting purposes become narrow, linear and segregated”. They advocate a mix of soft and hard ITh based on Checkland’s (1988) systems thinking. An example of hard systems thinking in relation to SIDM would be the spreadsheet analysis of expected cash flows based on predetermined algorithms for modelling the financial outcomes of decisions. An example of soft systems thinking would be to form a focus group to brainstorm the likely attitude or opinions of stakeholder groups such as customers, employees, users, suppliers and collaborative partners to gauge the reactions of vital parties to the proposal. In the case of human or social and relationship capital, this may be considered more appropriate. In large multinational firms the organisational culture and communication networks need to be developed to support this, where in smaller firms, the soft systems thinking may be undertaken by a single business owner or CEO, simply thinking through the implications of a project on their own. Most decision-makers would consult or take soundings from others before making strategic decisions, but we don’t currently know enough about how various actors integrate the hard and soft data available to them in SIDM (Harris et al., 2016).

The professional guidance on capital investment appraisal referred earlier in the chapter still presupposes that financial capital is the main type of capital requiring investment, which is a legacy from post-industrial revolution times when the majority of business entities manufactured a marketable product. However, post the digital revolution, with significant service businesses and on-line business activity, it could be argued that human, intellectual and social capital have come to the fore in terms of competitive advantage if not full “product” delivery. If the input from and impact on these capitals are difficult to measure after the event in corporate reporting terms, then they are surely more difficult to measure and predict beforehand for decision-makers. Due to the lack of published research in this field we can really only speculate as to how organisations might cope with this dilemma.

Could the IR framework help us to construct a new style of spreadsheet with a tab/sheet for each of the six capitals for example? This then leads to a problem of measurement and the issue of creating models that call for as much if not more narrative analysis than numerical analysis. Could the balanced scorecard type performance measurement framework (with additional dimensions for natural resources, sustainability and social responsibility) help to provide measures in the form of KPIs that may be used for both pre-event decision-making and post-event performance measurement and reporting?

The irony is that spreadsheets have made the calculation of discounted cash flow easy enough for DCF analysis to be in widespread use just at a time when interest rates (in the UK at least) are at an all-time low and the time value of money makes so little difference to the financial evaluation of projects. So, should we be keeping spreadsheets at all? Should we abandon spreadsheets and seek to give the narrative analysis more credibility?

Vesty et al. (2015) provide the only case evidence we seem to have so far on the potential for ITh in capital investment appraisal, with five case studies. Their emphasis and main interest was in sustainability, but at least this gives us some ideas about how firms might incorporate ITh into their SIDM. Of those five cases, the Yancoal coal mining subsidiary of the Chinese Yanzhou corporation gives particular insights into the environmental considerations of strategic projects, where examples of the non-financial information they consider include (Vesty et al., 2015, p. 98):

• Offset programs and expenditure (biodiversity)

• Social-related items in local communities

• Carbon emissions

• Energy and utility impacts

• Occupational health and safety issues

• Land rehabilitation

• Reputation impacts

In seeking guidance on incorporating the elements of IR into SIDM, it seems sensible to seek exemplars from firms for whom a specific capital is critical. Hence, the Water Corporation and Yancoal cases may be insightful for dealing with natural capital, for example with decision tables for assessing the impact on the environment of discharges to the environment, where firms in other sectors such as architecture and design may make better examples for intellectual capital. Vesty et al. (2015) conclude that the non-financial factors play a stronger role earlier on (at the early screening stage) in the capital investment appraisal process and that financial information plays a more important role later (at the board approval stage) in the process. They argue for a broader role for sustainability in investment appraisal and suggest that further attention should be given to the adoption of risk matrices in the process. They conclude that, “If accounting innovation as a result of integrated thinking is to endure, then accountants and accounting research must continue to play an important role in this change. To achieve this, the accounting profession will need to be at the centre of future developments” (Vesty et al., 2015, p. 104).

However, they do not suggest how the companies “integrated” the financial and non-financial analysis as such. The cases show examples of additional as opposed to integrated analysis. Also, the range of cases is focused on large organisations, mainly listed companies. There may be a lack of good case study access to professional firms, as they are typically not listed companies. Whilst we could not find persuasive examples of how the financial and non-financial elements may be integrated in investment appraisal as such, we did find an adaption of the balanced scorecard idea that incorporates multiple capital dimensions for performance measurement in work by McElroy and Thomas (2015) and Thomas and McElroy (2016) that may offer a way forward for investment appraisal.

McElroy and Thomas (2015, p. 9) present an annual multi-capital scorecard (MCS), which adopts a triple bottom line approach to analysing the impact on social, economic and environment capital in a context-driven scorecard. Like Kaplan and Norton (1996) they do not prescribe the content of the boxes in the scorecard. They recommend three steps in developing a MCS, from scoping to developing areas of impact to scorecard implementation. Their illustration takes three measures of impact on the environment (natural capital using IR language), water supplies, solid wastes and climate system. They present three measures of economic impact (financial capital), equity, borrowings and competitive practices. They then combine the other capitals into a social dimension, measuring the living wage, workplace safety and innovative capacity. Whilst their MCS has been designed to measure annual performance, it could easily be adapted to analyse the impact of long-term decisions, which may in turn improve company performance and sustainability.

We do not wish to over-speculate here, but it seems clear that either new ways of appraising strategic decisions have been developed in firms but have not been widely researched or documented, or new frameworks (along the lines of the multi-capital scorecard presented by Thomas and McElroy (2016)) are needed to guide this vital business activity. We therefore simply conclude that this is an area where more research is needed, including testing the MCS in a variety of contexts, for us to discover how firms may adopt a holistic or integrated approach to Accounting Information Systems for capital investment appraisal.

References

Abdel-Kader, M. G. and Dugdale, D. (1998). Investment in advanced manufacturing technology: a study of practice in large UK companies. Management Accounting Research, 9(3), 261–284.

Adler, R. W. (2000). Strategic investment decision appraisal techniques: the old and the new. Business Horizons, 43(6), 15–22.

Afful-Dadzie, E. and Afful-Dadzie, A. (2016). A decision-making model for selecting businesses in a government venture capital scheme. Management Decision, 54(3), 714–734.

Alkaraan, F. and Northcott, D. (2006). Strategic capital investment decision-making: a role for emergent analysis tools? A study of practice in large UK manufacturing companies. British Accounting Review, 38(2), 149–173.

Arnold, G. C. and Hatzopoulos, P. D. (2000). The theory-practice gap in capital budgeting: evidence from the United Kingdom. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 27(5–6), 603–626.

Bromwich, M. (1976). The Economics of Capital Budgeting. London: Penguin.

Busco, C., Frigo, M. L., Quattrone, P. and Riccaboni, A. (2013). Integrated Reporting: Concepts and Cases that Redefine Corporate Accountability. Switzerland: Springer.

Callahan, C. and Haka, S. (2004). Common accounting knowledge: the diffusion of discounted cash flow knowledge in the US. Working paper, Michigan State University, 1–58.

Carr, C. and Tomkins, C. (1996). Strategic investment decisions: the importance of SCM. A comparative analysis of 51 case studies in UK, US and German companies. Management Accounting Research, 7(2), 199–217.

CGMA (Chartered Global Management Accountants). (2014). Integrated thinking – the next step in integrated reporting. CGMA. www.cgma.org/integratedthinking.

CGMA (Chartered Global Management Accountants). (2016). Joining the dots: decision making for a new era. CGMA. www.cgma.org/joiningthedots.

Checkland, P. (1988). Soft systems methodology: an overview. Journal of Applied Systems Analysis, 15, 27–30.

Chiucchi, M. S. (2013). Measuring and reporting intellectual capital. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 14(3), 395–413.

Churet, C. and Eccles, R. G. (2014). Integrated reporting, quality of management, and financial performance. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 26(1), 56–64.

Drury, C. (1990). Counting the cost of AMT investment. Accountancy, 105(1160), 134–138.

Dumay, J., Bernardi, C., Guthrie, J. and Demartini, P. (2016). Integrated reporting: a structured literature review. Accounting Forum, 40(3), 166–185.

Eccles, R. and Krzus, M. (2010). One Report: Integrated Reporting for a Sustainable Strategy. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Eccles, R. and Krzus, M. (2014). The Integrated Reporting Movement. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Elmassri, M. M., Harris, E. P. and Carter, D. B. (2016). Accounting for strategic investment decision-making under extreme uncertainty. British Accounting Review, 48(2), 151–168.

Emmanuel, C., Otley, D. and Merchant, K. (1990). Accounting for Management Control, 2nd ed. London: Thomson.

Emmanuel, C., Harris, E. and Komakech, S. (2010). Towards a better understanding of capital investment decisions. Journal of Accounting and Organizational Change, 6(4), 477–504.

Flower, J. (2015). The international reporting council: the story of failure. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 27, 1–17.

Groot, T. and Selto, F. (2013). Advanced Management Accounting. London: Pearson.

Haka, S. F. (2007). A review of the literature on capital budgeting and investment appraisal: past present and future musings. In C. Chapman, A. Hopwood, and M. Shields (eds.), Handbook of Management Accounting Research (Vol. 2). North Holland: Elsevier, 697–728.

Harris, E. (1999). Project risk assessment: a European field study. British Accounting Review, 31(3), 347–371.

Harris, E., Emmanuel, C. and Komakech, S. (2009). Managerial Judgement and Strategic Investment Decisions. Oxford: Elsevier.

Harris, E. (2011). Project Management. Finance & Management Special Report SR33. London: ICAEW.

Harris, E., Northcott, D., Elmassri, M. and Huikku, J. (2016). Theorising strategic investment decision-making using strong structuration theory. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 29(7), 1177–1203.

Hirshleifer, J. (1958). On the theory of optimal investment decision. Journal of Political Economy, 329–352.

Huikku, J. and Lukka, K. (2016). The construction of persuasiveness of self-assessment-based post-completion auditing reports. Accounting and Business Research, 43(3), 243–277.

ICAEW (Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales). (2009). Investment Appraisal. Finance and Management Special Report SR27. London: ICAEW.

IFAC (International Federation of Accountants). (2008). Project Appraisal Using Discounted Cash Flow. An International Guidance to Good Practice. New York: IFAC.

IIRC (International Integrated Reporting Council). (2013). The International Integrated Reporting Framework. London: IIRC.

Jakobsen, M., Nørreklit, H. and Mitchell, F. (2010). Internal performance management systems: problems and solutions. Journal of Asia Pacific Business, 11(4), 258–277.

KPMG. (2015). Performance Reporting: An Eye on The Facts. A KPMG and ACCA Thought Leadership Report. London: ACCA

Kaplan, R. S. and Atkinson, A. A. (2015). Advanced Management Accounting. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall International.

Kaplan, R. S. and Norton, D. P. (1996). The Balanced Scorecard: Translating Strategy into Action. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

McElroy, M. W. and Thomas, M. P. (2015) The multicapital scorecard. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 6(3), 1–16.

Nørreklit, H. (2000). The balance on the balanced scorecard – a critical analysis of some of its assumptions. Management Accounting Research, 11(1), 65–88.

Oliver, J., Vesty, G. and Brooks, A. (2016). Conceptualising integrated thinking in practice. Managerial Auditing Journal, 31(2), 228–248.

Panko, R. R. (2006). Spreadsheets and Sarbanes-Oxley: regulations, risks and control frameworks. Communications of the AIS, 17, article 29.

Powell, S. G., Baker, K. R. and Lawson, B. (2009a). Errors in operational spreadsheets. Journal of Organizational and End User Computing, 21(3), 24–36.

Powell, S. G., Baker, K. R. and Lawson, B. (2009b). Impact of errors in operational spreadsheets. Decision Support Systems, 47(2), 126–132.

Ryan, P. and Ryan, G. P. (2002). Capital budgeting practices of the Fortune 1000: how have things changed? Journal of Business & Management, 8(4), 355–364.

Shank, J. K. and Govindarajan, V. (1992). Strategic cost management: the value chain perspective. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 4, 179–197.

SAICA (South African Institute of Chartered Accountants). (2015). Integrated Thinking: An Exploratory Survey. Johannesburg: SAICA.

Srithongrung, A. (2010). State capital improvement programs and institutional arrangements for capital budgeting: the case of Illinois. Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management, 22(3), 407–430.

Thomas, M. P. and McElroy, M. W. (2016) The MultiCapital Scorecard: Rethinking Organizational Performance. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing.

Vesty, G., Brooks, A. and Oliver, J. (2015). Contemporary Capital Investment Appraisal from a Management Accounting and Integrated Thinking Perspective: Case Study Evidence. Southbank, Australia: CPA Australia.