Outsourcing of Accounting Information Systems

Introduction

Outsourcing of information systems activities continues to grow. Companies regularly use a combination of employees, local vendors and offshore providers for their information systems services. In this way they can create the optimal combination to take advantage of best prices and talents worldwide. While offshore outsourcing is the form that seems to dominate the headlines, domestic outsourcing is also growing at a very fast pace (Overby, 2015). The demand for outsourcing services is notably driven by advances in cloud computing and the provision of business processes as a service (Deloitte, 2014). This same study noted that while information systems services are becoming a relatively mature outsourcing segment, finance and accounting services outsourcing is expected to grow significantly over the next few years. In light of these facts, it is important to understand what outsourcing is. It is also essential to recognise the key decisions a manager has to make when considering outsourcing of Accounting Information Systems activities.

This chapter starts by defining outsourcing, clarifying the difference with offshoring and providing examples of the numerous ways outsourcing can be used for Accounting Information Systems. Following this definition, the key decisions associated with outsourcing are described. The first is the decision to outsource an activity. Managers have to assess whether an activity is suitable for outsourcing. The second is the contract. Once outsourcing is chosen, the contract has to be designed to extract the best possible outcome from the vendor while protecting the client. Third, management of the relationship is explored. Parties have to actively communicate and exchange information to collaborate effectively. Fourth, the risk assessment of outsourcing contracts is discussed. Outsourcing is a major business decision requiring active risk assessment and appropriate risk mitigation. Finally, new managerial dilemmas posed by recent technological advances are outlined. The move of Accounting Information Systems to a cloud-based ecosystem of service providers is forcing managers to rethink how the accounting function is organised in the 21st century firm.

When trying to appreciate issues associated with the outsourcing of Accounting Information Systems, it is important to realise that a large proportion of issues are the same as the ones associated with outsourcing of information systems in general. Therefore, elements presented in this chapter that pertain to the outsourcing decision are not specific to accounting. These elements are as relevant for Accounting Information Systems as they would be for other types of systems. However, outsourcing of Accounting Information Systems, because of the importance of accounting data in the organisation, brings some specific challenges. These are discussed in the section detailing the managerial dilemmas.

Defining outsourcing

Outsourcing is fundamentally a make-or-buy decision. Companies can opt to use their own employees to perform a task or rely on a vendor to get the work done. When considering IT activities, companies can use their own infrastructure and staff to perform the activities or rely on suppliers to provide these as a service. This last option is called outsourcing. Formally, outsourcing is the decision to rely on an external party for a product or service instead of conducting the corresponding activities inside the organisation.

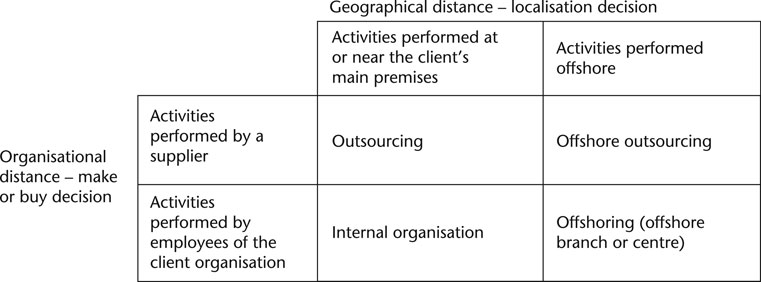

Outsourcing takes many forms. In some cases, activities are performed by a supplier’s employees inside the client’s premises. In those cases, the supplier emulates the behaviour of internal employees, ensuring daily interactions with internal staff. In other circumstances, services are provided from a different location. In those cases, companies are usually seeking economies of scale, letting their supplier pool activities with similar ones for other clients. In these situations, the activities can be conducted in the same region, or at great distance.

When companies select suppliers abroad to take advantage of other countries’ lower cost structures, outsourcing becomes offshore outsourcing (often shortened to “offshoring”). In those situations, services are offered from foreign locations. It is important to remember that while outsourcing always refers to the use of suppliers, offshoring may involve using the company’s own employees offshore. As shown in Figure 10.1, the decision to use a supplier and the decision to go offshore are two different decisions, even if they are made at the same time.

A brief history of outsourcing

While the popularity of IT outsourcing has grown significantly since the late 1980s, it is not a new phenomenon. As early as the 1960s time-sharing services were in place to allow different companies who did not have their own computers to use computer resources in shared mode (Abbate, 2001). By the early 1980s, there was a large group of suppliers offering IT outsourcing services, though these services were not very visible in the business world. In 1989, Kodak, which was seen as a sophisticated user of IT at the time, announced that its IT services would be outsourced (Wilder, 1989). The contract was large for those times and entailed the transfer of over 500 employees to the three chosen suppliers (Brown, 1990). This contract became highly publicised and led to several more contracts, often influenced by the legitimacy given to outsourcing by the Kodak-IBM arrangement (Loh and Venkatraman, 1992). It also signalled the entry of IBM into the IT service industry (IBM, 2002). In the following years, the outsourcing industry saw the signing of several multi-billion dollar contracts.

Figure 10.1 Outsourcing and offshoring decisions

The trend that followed outsourcing in the 1990s was offshoring. As shown in Figure 10.1, offshoring means that activities are transferred offshore. During that period companies were not necessarily seeking to transfer activities to suppliers. They were mostly assessing where to locate their activities. Taking advantage of rapidly falling telecommunication costs and an increasingly qualified workforce in low-wage countries, companies moved several of their IT activities and business processes overseas. While encountering some resistance in developed countries, this contributed to the overall productivity of organisations (Blinder, 2006). In several ways, the offshoring of IT services parallels the relocation of manufacturing activities observed in the second half of the 20th century. As the skills of workers in developing countries increased, offshore companies were able to offer very competitive services to companies worldwide. Because IT services are purely digital, moving them offshore was especially easy, facilitated by the development of the Internet.

Currently, outsourcing and offshoring have become part of the daily lives of managers. Client firms routinely use suppliers for IT services. This has been reinforced by the growth of cloud computing and cloud services. In general, most firms now eschew all-encompassing and very large contracts. These contracts, observed in the late 1990s, are not seen as ideal anymore. Companies use outsourcing more selectively, targeting the most appropriate services for this type of governance. They also call on multiple suppliers, taking advantage of the specific expertise of each one to gain access to expertise while avoiding lock-in problems.

Outsourcing of accounting systems

Outsourcing takes many forms and is used for many different types of activities, including Accounting Information Systems. Outsourcing can be used to develop and implement new Accounting Information Systems or to operate them once they are implemented. These arrangements for outsourcing accounting systems operations range from the mere provision of computer hosting services to contracting the whole accounting business process to an external provider. These various options are discussed in the following paragraphs.

Outsourcing the development of Accounting Information Systems

Outsourcing is often used to develop and implement new information systems. It comes in two main varieties: using a provider for the software and/or consultants to configure the software.

It is important to note that companies rarely rely on custom-made software nowadays. There is little need to develop software from scratch unless very specific needs must be addressed inside the organisation. This is rarely the case with most business activities. Companies mostly select off-the-shelf software packages from established vendors and configure them as required. There are many applications available, often embedded in larger toolkits like ERP packages. It is relatively easy for suppliers to develop a system that will serve the accounting needs of a myriad of firms (Zentz, n.d.). The fact that every company has accounting needs, combined with the standardisation provided by accounting standards, makes production of accounting software packages financially viable. For normal use, packaged solutions provide a faster and cheaper alternative to the development of new accounting systems (Cohn, 2014). Companies can purchase a package and configure it to their needs. In so doing, they also gain access to systems having been extensively tested for reliability and accuracy.

The configuration of the software is the second way outsourcing is used. When companies select a software package, they have to ensure that it is configured to fit their specific needs. This means that specific codes have to be created to reflect the activities of the company. Areas of business have to be established to enable the company to produce the required profit and loss statements, controlling documents (used by auditors) and all other required reports.

Configuring software requires a good understanding of the software itself, of accounting principles and of company operations. Adequate configuration of the accounting software will ensure that performance tracking and the information provided to managers will be correct and that regulatory requirements will be met.

Outsourcing the operation of Accounting Information Systems

Once the systems are configured and ready to use, outsourcing can be used to support operation of the systems. The first form of outsourcing for accounting systems simply consists of using a supplier to operate, on behalf of the client, the accounting systems. This form of outsourcing is probably the simplest. When the system is hosted by an external provider, it can still be used by employees of the firm who may not even know that the system is hosted externally.

Cloud-based solutions are used more and more for Accounting Information Systems. Cloud companies offer standardised solutions at very competitive prices through a remote infrastructure accessible through the Internet, in comparison to an on-premise infrastructure maintained by the client (Armbrust et al., 2010). This type of solution is typically less flexible than a traditionally configured one. A cloud solution is configurable, but to a lesser extent than traditional solutions (Weinhardt et al., 2009). Cloud systems will cover the basic needs of most companies, although solutions are becoming increasingly sophisticated. Gaps in functionality are usually filled through an ecosystem of applications that can be interconnected through the cloud (Rickmann et al., 2014).

Finally, operation of the system can also be outsourced through accounting intermediaries. These firms primarily offer accounting services, but use software (often from a cloud provider) to supply the accounting service to the company. This is usually referred to as business process outsourcing, in which a whole business process is performed by a third party (Lacity et al., 2011). In these situations, the client does not select the software, leaving this choice to the accounting service provider. Comparison between business process outsourcing and information systems outsourcing shows that both strategies share common motivations and patterns (Lacity et al., 2011).

Growth of outsourcing for accounting systems

Because they are well-documented and well-structured, accounting activities are easier to outsource than other, less-structured management activities. The trend of outsourcing accounting and financial activities and processes continues to grow. Analysts indicate a growth rate of 8% (Byer, 2013). This growth is in part fuelled by the expanding needs of clients. Outsourcing these activities enables clients to use the expertise of their suppliers to access analytics capabilities and make better use of financial information, which facilitates the standardisation of processes across multiple sites and countries (Mullich, 2013).

In light of the variety of outsourcing choices and the growth of outsourcing, it is important to understand how outsourcing decisions are made. What elements should be considered before deciding to outsource an activity?

The outsourcing decision

There have been numerous studies looking at the decision to outsource IT activities. Very thorough reviews of the outsourcing literature, outlining what variables can influence the outsourcing decisions, can be found in Dibbern et al. (2005) and Lacity et al. (2010). The following paragraphs present the key elements explaining the choice of outsourcing as a governance mode for an information systems activity.

Economic considerations

As mentioned earlier, outsourcing is the use of a supplier to perform an activity instead of relying on employees. One approach that has been extensively used to analyse this type of decision is from economics, more precisely Transaction Costs Economics. This approach looks at the costs associated with outsourcing. When a company contracts out an activity, it has to search for the best supplier, negotiate a contract, monitor the contract to ensure compliance, etc. All these activities are time-consuming and generate transaction costs. Even if a supplier is specialised and has a production cost advantage over the client, there will be situations in which the transaction costs will be too high for the transaction to be profitable to outsource. In those situations, the client reverts to internal governance.

Traditionally, transaction costs have been linked to two sources: asset specificity and uncertainty (Williamson, 1979). A specific asset is one that is unique to a specific transaction and that has no residual value for another transaction. If a firm controls a specific asset, it can ask a higher price of the company that needs the asset. The client firm will try to protect itself against such opportunistic behaviour, thus generating transaction costs (Williamson, 1979). The second element generating transaction costs is uncertainty. It takes many forms. First, there can be uncertainty about the nature of activities to perform. This means that the contract will need to establish contingencies, which are costly to develop (Williamson, 1979). The second form is uncertainty about the measurement of the activities. Activities that are difficult to measure entail additional transaction costs since much effort is needed to monitor the supplier to ensure it delivers the services promised (Alchian and Demsetz, 1972).

There is one exception to this logic of avoiding transaction costs. Companies will willingly pay higher transactions costs for activities that are infrequent in nature. Transactions organised within a firm have to be recurrent to ensure that employees and assets are used on a continuous basis. This means that companies are likely to outsource activities that are occasional to avoid hiring employees just for that purpose. In this case, they will be willing to accept higher than usual transaction costs (Williamson, 1979).

Asset specificity has not been found to be a significant factor in IT outsourcing decisions (Aubert et al., 2012; Lacity et al., 2010). It seems that most assets linked with IT activities are generic (hardware, software) and can be repurposed easily. The few assets that could be specific are likely to be associated with knowledge. In this case, they are difficult to include in contracts since they are not owned by the companies but instead are kept by employees. It is difficult to include the control of knowledge in a contract, just as it is difficult to control knowledge inside the minds of employees (Aubert and Rivard, 2016). This suggests that asset specificity does not seem to play a significant role when deciding to outsource an IT activity.

The variables that have been found to be the best predictors of outsourcing of information systems activities are all related to uncertainty in its various forms. Uncertainty around the type of activities to be delivered is a deterrent to outsourcing. If activities cannot be specified in advance in a contract, it becomes very difficult to outsource them. On the other hand, when activities are well standardised, they are much easier to detail in a contract and thus easier to outsource (Aubert, et al., 2012).

This means that companies considering outsourcing have to be able to predict the nature of their activities over a period of time at least as long as the contract. In the case of accounting activities, there is a core group of activities that are easy to predict. These activities are required for the organisation on an ongoing basis. Other activities may be more difficult to predict, notably when they are associated with changes in the organisation (mergers, acquisitions, spin-offs) that are not expected. Typically, organisations will sign contracts covering the core needs and will use separate arrangements to cover unexpected events as those events unfold.

Measurability is also very important. When a contract is signed, the client has to be able to assess the work of the supplier and the supplier has to be able to demonstrate that the services delivered meet specifications. When client and supplier cannot agree on the services delivered, both in quality and quantity, they cannot enforce a contract. This is easier said than done. In outsourcing contracts, the client cannot easily monitor services performed by the supplier and is usually unable to tell whether a problem is due to an unforeseeable event or to some negligence on the part of its supplier. Suppliers, knowing that their behaviour cannot be observed easily, can avoid responsibility for poor performance, or exaggerate their level of effort (and thus their costs) when informing their client (Aubert et al., 2003). Therefore, clients will try to outsource activities for which measurement is as easy as possible.

Political considerations

Transaction Costs Economics offers guidelines for identifying activities that should be outsourced. It is a rational method for determining the governance of IT activities in the organisation. However, there are cases in which organisational logic and best interest do not always align with individual logic and best interest. When assessing why different managers choose (or not) to outsource a set of activities, it is important to realise that they make those decisions in a way that often reflects their own personal benefit. In some instances, the use of outsourcing was introduced by managers to create impetus for a change they were promoting, to justify a budget increase for their department, to increase the visibility of their role, etc. (Lacity and Hirschheim, 1993).

In some instances, outsourcing is also used to benchmark activities. By asking suppliers to offer a service, companies obtain a cost comparison and can see how their own internal services are performing (Lacity and Hirschheim, 1993). Outsourcing can also be used to transform services. For instance, when trying to integrate different systems, some managers use outsourcing to increase the push for integration. It can serve as a means to raise awareness of the proposed change in other departments (finance, marketing, production) and draw attention on the possibilities offered by information systems. By bundling services in a large contract, IT costs suddenly become visible and receive more attention from the company’s board and leadership team.

Designing the contract

When outsourcing is used, it is important to remember that services will be managed through a contract between the client and its supplier. Agency theory provides key insights on the incentives, pitfalls and strategies that can be associated with such contract (Sappington, 1991).

When designing a contract, the client hopes that suppliers will work in a way that is in the client’s best interests. However, clients are aware that suppliers tend to work in their own best interests. Clients have to be aware of three challenges when trying to develop outsourcing contracts: adverse selection, imperfect commitment and moral hazard (Sappington, 1991).

Adverse selection is the first challenge to overcome when considering awarding an outsourcing contract to a supplier. If asked about its ability, a supplier is likely to overstate its capabilities to ensure it gets the contract. No supplier will admit being incompetent. This suggests that contracts should be designed in a way that discourages the less capable suppliers and encourages the competent ones. In IT, contracts have traditionally been labelled “time and material”, in which the client and the supplier agree on hourly rates for work, but for which the number of hours remain flexible. These contracts are attractive for less competent suppliers, since they are likely to need more hours (and make more money) than efficient suppliers. There are also fixed-price contracts, for which the total price is agreed in advance and for which the supplier becomes responsible to exert the efforts required to deliver the service promised. These contracts are more likely to attract efficient suppliers, since efficient suppliers are more likely to make a profit (by requiring less hours) than inefficient ones. The caveat is that the deliverables have to be clearly specified for such contracts to be feasible. In some cases, this is relatively easy to do. In other circumstances, the definitive specifications may not be available when the contract is signed.

Imperfect commitment represents the difficulty any party faces in promising something and honouring its promise. Very often, in contracts, unexpected events arise and parties will use these surprises to renege on their promises. For example, suppliers can claim that requirements were not clear enough and seek to increase the price initially agreed upon for a piece of software. Contractual measures preventing imperfect commitment are difficult to implement. They often rely on a long-term horizon. If a supplier hopes to secure additional contracts in the future, it may be more “honest” in its early engagements with the client. Bonds are sometimes used for information systems projects, but not very frequently. In IT outsourcing, the promise of future contracts and the protection of reputation are probably the strongest incentives for a vendor to remain committed to its promises (Aubert et al., 2003).

Finally, IT outsourcing is vulnerable to moral hazard. Moral hazard is created by the client’s inability to observe what the supplier is doing. The supplier can therefore claim that it is exerting great efforts and that poor performance is due to external circumstances. It is very difficult for the client to challenge these claims successfully. Examples of behaviour falling under the moral hazard label include cheating, shirking, free-riding, cost padding, exploiting a partner or simple negligence. In order to curb moral hazard, clients have to rely on competition. Multi-sourcing is often used in those cases. If more than one supplier knows the client firm and systems, then any under-performing supplier can be replaced easily. It becomes easier to press suppliers for better prices and higher quality (Wiener and Saunders, 2014).

Designing the contract is only a first step in ensuring a good outsourcing arrangement. Outsourcing relationships have to be managed throughout the duration of the contract.

Managing the contract

When managing outsourcing contracts for Accounting Information Systems it is important to consider two aspects of contract management: formal and informal (Barthélemy, 2003). Both aspects are important to ensure a good working relationship with the supplier and a satisfactory outcome for the client.

The formal part involves managing the activities associated with service level agreements and other elements directly associated with the contract. Every contract is expected to explicitly define the responsibilities of each party, how activities are measured, who owns each process, etc. (Goo et al., 2009). Agreements are expected to be as clear and complete as possible, dictating expected performance levels and associated penalties when these are not met (Kim et al., 2013). These elements have to be actively tracked to ensure that the outsourcing relationship is successful, notably that it generates the cost advantages expected by the client (Barthélemy, 2003).

Good contract management serves as a foundation for a good relationship between the client and the supplier. Such a contractual foundation enables client and supplier to establish common norms and ultimately trust in the relationship (Goo et al., 2009). However, the formal elements associated with management of the contract are not the only elements of the outsourcing relationship that have to be managed. Relationship management is essential and includes all the mechanisms used to work with the supplier after the contract is signed (Qi and Chau, 2012).

These relationship mechanisms traditionally enable client and supplier to exchange information about the needs of the client and the activities performed. For example, coordination will involve a series of committees bringing together personnel and executives from the client and the vendor. Escalation of any issue will follow a well-established path (Balaji and Brown, 2014). Relationship management can also include social events between the parties, informal meetings and other integration activities between the client and the vendor (Balaji and Brown, 2014).

All these activities increase knowledge-sharing between the parties. The client will take advantage of these communication forums to share future growth plans with the vendor, who in turn can plan ahead, offer information about technological opportunities and support the client beyond the simple execution of the activities. The quality of the communication between the parties is very important for a successful outsourcing relationship (Qi and Chau, 2012).

When performed consistently, relationship management enables the creation of shared values. These greatly facilitate interactions between the client and vendor (Goo et al., 2009). A combination of formal contractual management and informal relationship management has been found to be the most satisfying solution for outsourcing management. It enables the client to get the best combination of short-term gains from the vendor and long-term performance from the outsourcing strategy (Barthélemy, 2003).

Risk assessment

Like any other business activity, the outsourcing of Accounting Information Systems entails some risk. These operational risks have to be adequately assessed, measured and reported.

IT outsourcing risk has traditionally been measured in terms of risk exposure, which is defined as a combination of the probability that an undesirable outcome associated with the contract will occur and the magnitude of the loss associated with this outcome (Aubert et al., 2005).

There are many potentially undesirable outcomes associated with outsourcing contracts. Unexpected costs are the most common and can come from high transition costs, lock-in situations, costly contractual amendments, escalation or hidden costs. The client can also experience reduced quality of service, lose organisational competencies and face litigation (Aubert et al., 2005; Earl, 1996). Finally, the client can face compliance issues if the outsourcing contract is not set up properly (Gandhi et al., 2012). The potential damage associated with each of these possible undesirable outcomes has to be weighed.

Table 10.1 Risk factors

Associated with the client: |

• Client’s lack of experience or expertise with the outsourced activity • Client’s lack of experience and expertise with contract management • Client’s lack of experience with outsourcing |

Associated with the vendor: |

• Supplier’s lack of experience and expertise with the activity outsourced • Supplier’s size • Supplier’s financial instability |

Associated with the interaction or with the activities in the contract: |

• Poor cultural fit between client and supplier • Size of the contract • Interdependence between the activities in the contract and the activities kept inside the firm • Measurement problems • Task complexity |

Environmental characteristics |

• Technological discontinuity • Uncertainty about the legal environment |

The likelihood of each undesirable outcome can be determined by looking at a series of associated risk factors, which act as proxies for the probability of an undesirable outcome. This approach is common to many fields. For example, when assessing the risk of a heart attack, physicians will look at the associated risk factors: smoking, drinking, lack of physical exercise, poor dietary habits, genetic antecedents, etc. These, in turn, can lead directly to risk management strategies.

For IT outsourcing, the most common risk factors are presented in Table 10.1 (Aubert et al., 2005). These factors are characteristics of the client, the vendor, the activities themselves or the environment in which the company operates.

It is important to note that these characteristics will vary with each situation and the type of outsourcing chosen. For instance, evidence suggest that cloud vendors carry more debt (relative to assets) than non-cloud ones, compromising their financial stability (Alali and Yeh, 2012).

Managing the risk of an outsourcing arrangement thus involves the following steps: (1) evaluating the impact of possible negative outcomes, (2) evaluating the various associated risk factors to determine the likelihood of each possible negative outcome and (3) devising corresponding risk mitigation mechanisms. While a full description of these mitigation mechanisms is beyond the scope of this chapter, one can easily see that risk factors offer a first source of mitigation mechanisms. Once the client knows what the “sources” of risk are, it can adjust its strategy to reduce the risk. For example, if the highest risk factors are associated with the vendor, the client may decide to select a better suited vendor. If the highest risk factors are associated with the client, it can decide to get additional expertise before entering an outsourcing relationship, or gain experience by first awarding a small and easily monitored contract. Similarly, activity-specific risk factors can be managed by modifying the portfolio of activities considered for outsourcing. Each category of risk factors listed in Table 10.1 has to be evaluated carefully before finalising the outsourcing decision.

In most organisations risk has to be assessed and reported on a regular basis. Outsourcing is a significant endeavor for an organisation. It can provide significant benefits. However, it is not a risk-free solution. Adequate risk reporting and management is essential when considering outsourcing as a solution for information systems activity.

Future managerial dilemmas in Accounting Information Systems outsourcing

Accounting Information Systems are constantly evolving. In terms of technological platforms, a decade ago the main change was the integration of accounting systems into larger software packages (Sutton, 2006). More recently, the changes mostly consist of advances in cloud computing and service providers (Asatiani and Penttinen, 2015). These advances are not only changing how accounting information is produced and recorded in organisations, but also how the accounting function is organised. These changes pose new dilemmas for managers considering exploiting these technological advances.

Data accessibility and confidentiality

When introducing a vendor, the company gives a third party access to its accounting systems. What are the consequences of this access? On one hand, it might reduce the security of the data since the systems can be accessed on public networks, shared technological infrastructure and by more people, some of whom are not even employees of the firm. On the other hand, it might increase security since the third party, not being part of the organisation, has no incentive to tamper with the data since it is not concerned with its operations.

Insights can be gained from studies of auditing outsourcing. It has been observed that internal auditors are less objective than auditors from an external provider (use of outsourcing). The internal auditor, being an employee, is more vulnerable to internal pressures, which could affect its recommendations (Ahlawat and Lowe, 2004). This provides support for the idea that outsourcing Accounting Information Systems is more secure. The vendor’s employees have nothing to gain (and probably a lot to lose) by tampering with the data and are more isolated from pressures emanating from the client than internal employees would be. This means that the risk of data being altered is probably lower when the systems are outsourced. In addition, the use of an external provider for accounting activities can also lead to knowledge-sharing, which can benefit the company (Prawitt et al., 2012).

Data ownership and portability

The proliferation of cloud computing in recent years has exposed a new challenge with Accounting Information System outsourcing. In some cases, client companies sign a contract directly with their cloud provider. In other cases, the contract is signed with an accounting firm offering the accounting service. This accounting firm, in turn, has a contract with a cloud provider to host the system (Asatiani and Penttinen, 2015). In those situations, who owns the client company’s data? Is it the client or is it the accounting firm? It turns out that this can be a muddy situation and in some cases the client firm might actually not control its own data (Macpherson, 2014). Depending on the type of contract signed, the client company could be locked-in with the accounting firm. Even cloud providers take the time to explain these differences and advise clients to have a clear discussion with their accounting firm before agreeing on an outsourcing contract (Ridd, 2014).

Data integrity and regulatory compliance

Unlike other types of organisational information, the production of accounting information and financial statements is subject to regulation. Regardless of the form of the outsourcing arrangement considered, the ultimate responsibility for integrity of the information produced by accounting systems lies with the organisation, not with the cloud or service provider. If a cloud or service provider fails to meet reporting standards and requirements due to a technological or process breakdown, the organisation can incur a risk of penalties for non-compliance. However, if the organisation does not have the resources or competence to keep up-to-date with regulation, the cloud or service provider might be in the best position to do so on its behalf.

While some cloud and service providers hire independent auditors to provide assurances that their practices follow regulatory standards, managers should also develop internal controls to assess their supplier’s compliance. The challenge in developing such controls lies in the fact that the accuracy and integrity of accounting information can be difficult to verify without independently reprocessing the transactions that produced the accounting information in the first instance. Also, the production of accounting information will tend to become fragmented across an ecosystem of cloud providers, which will complicate tracing the source of integrity and non-compliance problems.

Future research

A significant body of knowledge on outsourcing has been developed as outsourcing became commonly used. However, the forms outsourcing can take are increasingly complex. This creates several opportunities for additional research on Accounting Information Systems outsourcing.

For example, we now observe several layers of contracting. Contracts are nested. Vendors sub-contract some services to other providers, who in turn use the capabilities of external sources (Jansen, 2011). These layers of sub-contracts dilute the knowledge related to the activities performed and the data used and can limit the accountability of vendors. At the same time, they enable more complete services at very competitive prices. How should contract design and reporting mechanisms evolve to take into account the layering of contracts? Most of the literature has been looking at the relationship between a client and a vendor, or between a client and multiple vendors. What happens when the vendor is also a client in another relationship?

Another area in which research is needed is the international dimension of outsourcing and offshoring. When activities are managed by vendors, they can be moved from one country to another to take advantage of different cost structures. The data can be stored in one country while the employees working with it are in other countries. This creates risks (Nassimbeni et al., 2012). Regulations differ from one country to another and understanding each country’s privacy laws, government surveillance strategies and intellectual property regulation is a challenge. In addition, these can change depending on political pressures. New risk management strategies will need to be developed to assess and manage those risks.

The compliance challenge associated with the practices of suppliers and their sub-contractors also require additional research efforts. How managers organise accounting functions in response to such dilemmas is an interesting line of inquiry. Data must be traced through an increasingly complex maze of systems. Auditing cannot be an afterthought. Auditing strategies have to be developed in parallel with contract development to ensure their soundness. Even when auditing strategies are being developed (Wang et al., 2015), how to implement them into auditing standards and practices and how to embed them into contracts remains a challenge.

Conclusion

The use of outsourcing is growing steadily. Companies use it to increase their flexibility and adapt to changes in regulations or in technological landscapes (Deloitte, 2014). For Accounting Information Systems, the outsourcing option has to be considered. Managers have to assess the extent to which their activities are predictable and measurable. The more they are, the better candidates they are for outsourcing. Managers must remain aware that rational motives may not be the only ones at play when considering outsourcing decisions. Political games may influence the decisions.

Once the decision to outsource is taken, it is important to devise a contract that will motivate the vendor to exert maximal effort. The contract should also protect the client from any lock-in situation. This is the only way to ensure that the client can switch suppliers easily and thus benefit from the competition between them. The relationship between client and supplier has to be managed. Beyond the contract, the clients will keep communication channels alive to ensure their suppliers have the information required to provide good service. As with any major decision, managers have to conduct a thorough risk assessment of the outsourcing decision. Outsourcing can lead to some negative events and regular monitoring of risk factors is essential. The use of a third party, the vendor, for accounting activities brings potentially positive and negative consequences. Managers will have to recognise that good outsourcing management is a balancing act. The challenge is to get most of the advantages of each governance mode while avoiding the pitfalls.

References

Abbate, J. (2001). Government, business and the making of the internet. Business History Review, 75(1), 147–176.

Ahlawat, S. S. and Lowe, D. J. (2004). An examination of internal auditor objectivity: in-house versus outsourcing. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory, 23(2), 147–158.

Alali, F. A. and Yeh, C. L. (2012). Cloud computing: overview and risk analysis. Journal of Information Systems, 26(2), 13–33.

Alchian, A. A. and Demsetz, H. (1972). Production, information costs, and economic organization. The American Economic Review, 62(5), 777–795.

Armbrust, M., Fox, A., Griffith, R., Joseph, A. D., Katz, R., Konwinski, A., Lee, G., Patterson, D., Rabkin, A., Stoica, I. and Zaharia, M. (2010). A view of cloud computing. Communications of the ACM, 53(4), 50–58.

Asatiani, A. and Penttinen, E. (2015). Managing the move to the cloud – analyzing the risks and opportunities of cloud-based Accounting Information Systems. Journal of Information Technology Teaching Cases, 5(1), 27–34.

Aubert, B. A., Houde, J. F., Patry, M. and Rivard, S. (2012). A multilevel analysis of Information Technology outsourcing. Journal of Strategic Information System, 21(3), 233–244.

Aubert, B. A., Patry, M. and Rivard, S. (2005). A framework for Information Technology outsourcing risk management. Database, 36(4), 9–28.

Aubert, B. A Patry, M. and Rivard, S. (2003). A tale of two contracts: an agency-theoretical perspective. Wirtschaftsinformatik, 45(2), 181–190.

Aubert, B. A. and Rivard, S. (2016). A commentary on “The role of transaction cost economics in information technology outsourcing research: a meta-analysis of the choice of contract type”. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 25(1), 64–67.

Balaji, S. and Brown, C. V. (2014). Lateral coordination mechanisms and the moderating role of arrangement characteristics in information systems development outsourcing. Information Systems Research, 25(4), 747–760.

Barthélemy, J. (2003). The hard and soft sides of IT outsourcing management. European Management Journal, 21(5), 539–548.

Blinder, A. S. (2006). Offshoring: the next industrial revolution? Foreign Affairs: New York, 85(2), 113.

Brown, B. (1990, January 15). Kodak turns nets over to IBM and DEC. Network World, 7(3), 1, 61.

Byer, F. (2013). Financial outsourcing services seen growing 8 percent annually through 2017. Accountingweb. Retrieved September 19, 2017, from www.accountingweb.com/technology/trends/financial-outsourcing-services-seen-growing-8-percent-annually-through-2017.

Cohn, C. (2014). Build vs. buy: how to know when you should build custom software over canned solutions. Forbes. Retrieved September 19, 2017, from www.forbes.com/sites/chuckcohn/2014/09/15/build-vs-buy-how-to-know-when-you-should-build-custom-software-over-canned-solutions/.

Deloitte. (2014). Deloitte’s 2014 Global Outsourcing and Insourcing Survey 2014 and Beyond. Retrieved September 19, 2017, from www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/us/Documents/strategy/us-2014-global-outsourcing-insourcing-survey-report-123114.pdf.

Dibbern, J., Goles, T., Hirschheim, R. and Jayatilaka, B. (2005). Information systems outsourcing: a survey and analysis of the literature. ACM Sigmis Database, 35(4), 6–102.

Earl, M. J. (1996). The risks of outsourcing IT. Sloan Management Review, 37(3), 26.

Gandhi, S. J., Gorod, A. and Sauser, B. (2012). Prioritization of outsourcing risks from a systemic perspective. Strategic Outsourcing: An International Journal, 5(1), 39–71.

Goo, J., Kishore, R., Rao, H. R. and Nam, K. (2009). The role of service level agreements in relational management of information technology outsourcing: an empirical study. MIS Quarterly, 119–145.

IBM Corporate Archives (2002, May). IBM Global Services: A Brief History. Retrieved September 19, 2017, from www-03.ibm.com/ibm/history/documents/pdf/gservices.pdf.

Jansen, W. A. (2011). Cloud hooks: security and privacy issues in cloud computing. System Sciences (HICSS), 2011 44th Hawaii International Conference, IEEE, 1–10.

Kim, Y. J., Lee, J. M., Koo, C. and Nam, K. (2013). The role of governance effectiveness in explaining IT outsourcing performance. International Journal of Information Management, 33(5), 850–860.

Lacity, M. C. and Hirschheim, R. (1993). The information systems outsourcing bandwagon. Sloan Management Review, 35(1), 73.

Lacity, M. C., Khan, S., Yan, A. and Willcocks, L. P. (2010). A review of the IT outsourcing, empirical literature and future research directions. Journal of Information Technology, 25(4), 395–433.

Lacity, M. C., Solomon, S., Yan, A. and Willcocks, L. P. (2011). Business process outsourcing studies: a critical review and research directions. Journal of Information Technology, 26(4), 221–258.

Loh, L. and Venkatraman, N., (1992). Diffusion of information technology outsourcing: influence sources and the Kodak effect. Information Systems Research, 3(4), 334–358.

Macpherson, S. (2014, April 30). Why You Should Always Hold Your Own Cloud Software Subscription. Retrieved September 19, 2017, from www.digitalfirst.com/you-hold-software-subscription/.

Mullich, J. (2013). The benefits of outsourcing finance and accounting. Forbes. Retrieved September 19, 2017, from www.forbes.com/sites/xerox/2013/07/12/the-benefits-of-outsourcing-finance-and-accounting/.

Nassimbeni, G., Sartor, M. and Dus, D. (2012). Security risks in service offshoring and outsourcing. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 112(3), 405–440.

Overby, S. (2015). Top 5 factors driving domestic IT outsourcing growth. CIO. Retrieved September 19, 2017, from www.cio.com/article/2946676/outsourcing/top-5-factors-driving-domestic-it-outsourcing-growth.html.

Prawitt, D. F., Sharp, N. Y. and Wood, D. A. (2012). Internal audit outsourcing and the risk of misleading or fraudulent financial reporting: did Sarbanes-Oxley get it wrong? Contemporary Accounting Research, 29(4), 1109–1136.

Qi, C. and Chau, P. Y. (2012). Relationship, contract and IT outsourcing success: evidence from two descriptive case studies. Decision Support Systems, 53(4), 859–869.

Rickmann, T., Wenzel, S. and Fischbach, K. (2014). Software ecosystem orchestration: the perspective of complementors. Twentieth Americas Conference on Information Systems, Savannah, Georgia.

Ridd, C. (2014). Managing your Xero subscription. Xero. Retrieved September 19, 2017, from www.xero.com/blog/2014/04/managing-xero-subscription/.

Sappington, D. E. (1991). Incentives in principal-agent relationships. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 45–66.

Sutton, S. G. (2006). Enterprise systems and the re-shaping of accounting systems: a call for research. International Journal of Accounting Information Systems, 7(1), 1–6.

Wang, J., Chen, X., Huang, X., You, I. and Xiang, Y. (2015). Verifiable auditing for outsourced database in cloud computing. IEEE Transactions on Computers, 64(11), 3293–3303.

Weinhardt, C., Anandasivam, A., Blau, B., Borissov, N., Meinl, T., Michalk, W. and Stößer, J. (2009). Cloud computing: a classification, business models and research directions. Business & Information Systems Engineering, 1(5), 391–399.

Wiener, M. and Saunders, C. (2014). Forced coopetition in IT multi-sourcing. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 23(3), 210–225.

Wilder, C. (1989). Kodak hands processing over to IBM. Computerworld, 23(31), 1.

Williamson, O. E. (1979). Transaction-cost economics: the governance of contractual relations. The Journal of Law and Economics, 22(2), 233–261.

Zentz, M. (n.d.). Custom vs. off-the-shelf software. Marketpath. Retrieved September 19, 2017, from www.marketpath.com/digital-marketing-insights/custom-applications-vs-off-the-shelf-software.