Chapter 23

The Changing Order

And slowly answer’d Arthur from the barge: “The old order changeth, yielding place to new.”

—Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Morte d’Arthur (1842)

Tennyson’s poem would have been familiar to Morgan, Roosevelt, and other participants in the Panic of 1907. It was a staple of assignments for high school and college students in the late nineteenth century. And its reference to a changing order must have haunted them as they dealt with the lingering effects of the panic. The old order was changing. How did the Knickerbocker emerge from its calamity—and what did this emergence presage for trust companies? Did the Progressive Movement sustain its momentum beyond the Federal Reserve Act and other achievements of President Wilson’s first term? And what became of the leading protagonists in the Panic of 1907?

The Knickerbocker Trust Company

One of the sharpest points of contention in 1907 and since was the failure of the New York City financial community to assist the Knickerbocker Trust Company. After its suspension on October 22, 1907, the Knickerbocker went into the hands of receivers. The New York State Superintendent of Banks oversaw a resolution process that hinged on two questions. First, was the trust company insolvent, or was it merely illiquid? Chapter 9 discusses the significance of this question. Second, if the trust company was solvent, what steps should be taken to resume operation?

To answer the first question, the Superintendent of Banks ordered an inventory and appraisal of the trust company’s assets, which were completed on February 29, 1908. The appraisers determined that the market value of assets of $49.1 million had fallen 13 percent from the trust company’s book value of assets of $56.5 million. These asset values compared to total deposits of about $47 million.1 Superficially, the small positive difference between the appraised asset value and the claims of depositors would suggest that the Knickerbocker’s problem was illiquidity, not insolvency. On that basis, a rescue might have been justified, an insight that probably motivated critics of the decisions of Mercantile National Bank, the NYCH, and J.P. Morgan not to assist the Knickerbocker on October 22.2

However, to judge the decision not to rescue the Knickerbocker requires better insights than those afforded by the appraisal. Essentially, one would want to know the quality and appraised value of assets on October 22. Hannah’s (1931) discussion suggests that the book value was measured somewhat before the onset of the Panic of 1907, and that the markdowns in appraised value reflected market conditions as of the appraisers’ report of February 29, 1908. The four‐month lapse poses very different capital market conditions. The extent of (in)solvency as of October 22, 1907 remains an important topic for future research.

As regards the second question, about recapitalization of the Knickerbocker, committees of depositors quickly formed to offer restructuring plans. One committee, representing large depositors, was advised by Louis Untermyer (the same person who led the Pujo Committee hearings five years later). A second committee of depositors, under the guidance of Herbert L. Satterlee (J. P. Morgan’s son‐in‐law) represented a larger pool of depositors, of mainly medium‐ and small‐dollar‐value accounts. Satterlee’s committee issued its proposal on November 29, prompting Untermyer’s committee to criticize the proposal and offer its alternatives. Contentious issues were how fast the depositors could withdraw funds, whether they would be forced to accept illiquid securities in exchange for their deposits, and the composition of the new board of directors.

Slowly, most depositors swung to support Satterlee’s proposal, while a few large depositors held out. Public endorsements of Satterlee’s plan from celebrity depositors such as Mark Twain and former President Grover Cleveland helped to attract support. Finally, with 90 percent of depositors in accord, Satterlee petitioned the New York State Superintendent of Banks to approve the reorganization plan, which he did.

The Knickerbocker Trust Company reopened on March 26, 1908. About $1.5 million in net new deposits flooded in the first day, reflecting “a cheerful, almost holiday mood” among customers in the lobby, a large bouquet of flowers from Farmers Loan and Trust Company, and the arrival of numerous telegrams of congratulation. Satterlee said, “In all a fine example of what confidence will do. It was the depositors themselves who made the reopening possible, and to them belongs the credit. The hundreds who were at first worried over the outcome and at a loss to know what to do came to line when they found that most of their fellows had confidence in the bank’s solvency.”3

The Knickerbocker recovered and repaid its depositors ahead of schedule. In 1912, Columbia Trust Company acquired the assets of the Knickerbocker to form the Columbia‐Knickerbocker Trust Company. In 1923, the company was acquired by Irving Trust Company. And in 1988, Irving Trust was acquired by Bank of New York, in a hostile takeover. In 2007, Bank of New York combined with Mellon Financial to form BNY Mellon, now the world’s largest custodian bank and securities services company.

The Knickerbocker’s descendants over the century after the Panic of 1907 illustrated the broader consolidation in the financial services industry: from 1907 to 2007, the number of depository institutions in the United States declined by about two‐thirds,4 along with growing concentration. By 2018, the four largest banks held 44 percent of all deposits.5

The High Tide of Progressivism

After 1913, the Progressive Movement began to wane as the country slipped into another recession. Fearing political gains by the Republicans, Wilson tempered his progressivism. Next, events in Europe distracted public opinion, prompting the New York Stock Exchange to close for more than four months with the onset of war in 1914.6 War concerns diverted resources and attention from social issues to foreign policy.

Republicans regained control of Congress in the elections of 1918. The war ended on November 11, 1918, but not before Congress passed laws to limit espionage and seditious activities. Civil libertarians vehemently protested these laws. And anarchists reacted to these with civil unrest. On September 16, 1920, anarchists exploded a bomb outside the new offices of J. P. Morgan & Company at 23 Wall Street, killing 33 people and injuring 400.7 The explosion closed the New York Stock Exchange for a day and left some scars on the side of the building that are visible a century later, but otherwise barely interrupted the work in the financial community. On the left wing of American politics, liberals recoiled from the resurgence of violence by radicals on the far left. With the deaths of Roosevelt in 1919 and Wilson in 1924, progressivism lost its most prominent champions.

The presidential election of 1920 displaced progressivism as the dominant impetus in American politics. From 1920 to 1932, Republicans occupied the White House, overseeing a retreat from progressive activism. But the Great Crash of October 1929 marked the onset of a scenario worse than 1907: panic, bank failures, economic contraction, and outcry for government intervention. President Herbert Hoover initially sought to mobilize volunteerism for relief efforts by the private sector. As the Depression deepened, Hoover turned to a program of fiscal stimulus by infrastructure spending. And he approved legislation to authorize the Fed to lend directly to businesses. However, these remedies failed to turn the tide by the end of Hoover’s first term.

After the 1932 election of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and a new Congress, the political pendulum swung back to populist and progressive ideas. In 1933, Congress enacted regulations covering a raft of ills, not least those perceived of Wall Street in the first decade of the century. Motivated by hostility toward financial elites and market abuses that allegedly spawned the Great Crash, Congress passed the Glass–Steagall Act of 1933 separating commercial banking and investment banking. The same act established federal deposit insurance that would help to quell bank depositors’ fears.

Financial institutions were no longer allowed to both take deposits and underwrite securities offerings. This proved to be a pivotal event in American financial markets that forced J. P. Morgan & Company to choose to limit its activities strictly to commercial banking. Morgan partner Henry S. Morgan (son of J. Pierpont Morgan, Jr.) led several J. P. Morgan & Company partners into forming the investment bank Morgan Stanley. The division of the financial services industry held until 1999, when Congress repealed the provisions of Glass–Steagall separating commercial and investment banking.

The Change Agents

The Panic of 1907 and its aftereffects turned the glare of public attention onto many individuals, either for what they did or did not do. Individually, the actions they took and views they espoused illustrated the significance of human agency as an influence on the Panic. Collectively, they represented the struggle for change from old to new orthodoxies in finance and public policy. What became of these change agents after their star turn in the crisis and its outcome?

Outsiders

F. Augustus Heinze met his downfall in the Panic of 1907. After his brother Otto’s failed attempt to corner the stock of United Copper Company, Augustus was ousted from the Mercantile National Bank and took losses on falling stock prices in United Copper and other securities. His aspiration to enter the financial elite of New York lay in tatters.

In the wake of the panic, Heinze’s firm was placed in the hands of a receiver. Heinze was indicted on 16 counts of financial malfeasance and various breaches of banking law. According to his brother Otto, Augustus maintained that he was blameless and that “the old line of bankers were bringing about a money panic in order to get rid of the new class of financiers and the new trust companies.”8 The government’s case against Heinze drew headlines, though a journalist noted that he “maintained cool, unruffled, defiant, hedging behind constitutional rights.”9 Then in 1909 the court acquitted him.

Nonetheless, Heinze’s reputation remained tarnished, the slump in copper prices had crushed his mining interests, his relationships with his brothers had dissolved, and his health suffered. Augustus again went West, where he purchased mining operations in Idaho and British Columbia, intending to turn them profitable. But a lawsuit by a creditor drew him back to New York in 1914. To finance his purchase of control in Mercantile National Bank in 1907, Heinze had given a note to the seller for $630,000, on which Heinze defaulted, following the Panic. Under cross‐examination, Heinze testified that although he was president of the Mercantile, he never inspected its books, and instead left such tasks to a vice president of the bank.10 The court awarded the seller $1.2 million in restitution and damages. In turn, Heinze sued Morse, who had defaulted on a pledge to finance the purchase with $500,000—however, Augustus died before the case could be heard.

Heinze’s biographer, Sarah McNelis, wrote that “After the Panic of 1907, he was vastly older, disillusioned, almost distraught in appearance; although he was still quite young, his hair was almost white.”11 Only 44 years old, the garrulous bon vivant died alone on November 4, 1914, at his home in Saratoga, New York, from cirrhosis of the liver.12 He left an estate estimated at $1.5 million13 ($44 million in purchasing power in 2022).

Charles W. Morse, the confederate of F. Augustus Heinze, has been described as “physically ugly, amoral, rich beyond reason,” rapacious, and shady.14 In January 1910, Morse was convicted of misappropriating bank funds from the Bank of North America (a bank in which he had a controlling interest) and sentenced to 15 years in prison. He began his sentence at the federal penitentiary in Atlanta, where he met Charles Ponzi, who would later become famous for the eponymous pyramid scheme; Ponzi was serving a two‐year sentence on a charge of sponsoring illegal immigrants.

Morse believed that he had done nothing wrong that did not occur daily in the financial community. Therefore, he launched a vigorous effort to spring himself, with the assistance of lawyers, lobbyists to the White House, and journalists such as Clarence W. Barron. Mysteriously, Morse grew ill; it was feared that he would die quickly. President Taft commuted Morse’s sentence in January 1912 and released him from prison. Thereupon, Morse fled to Europe, after which it was revealed that Morse’s “illness” was due to eating soap shortly before his medical exams.15 In the fall of 1912, Morse returned to the United States and formed a new steamship company, having sold his Consolidated Lines to J. P. Morgan at a steep discount. With the advent of World War I, he bid on ship construction projects for his U.S. shipping company and won contracts for 36 vessels. In 1922, Morse was indicted for fraud and war profiteering but was acquitted.16 He suffered strokes in the late 1920s and was judged incompetent to manage his own affairs. Morse died of pneumonia on January 12, 1933.

Charles T. Barney, president of the Knickerbocker, was forced out by the failure of the firm. He died from a self‐inflicted gunshot wound on November 14, 1907, and was survived by his wife, Lily Whitney Barney, and their two sons. Lily Barney sold their home in Manhattan’s Murray Hill district in 1912 and dropped from public view.

His demise might be regarded as indirect or collateral damage of the Panic. He had been affiliated with Charles Morse in some ventures but was not a participant in the attempted corner on United Copper. The Knickerbocker had extended a loan to Charles Morse, collateralized by securities of doubtful value. However, write‐off of the loan ($200,000) was not enough to destabilize the Knickerbocker. The appraiser’s report in February 1908 suggested solvency and seemed to affirm Barney’s assertions in October that the trust company was solvent but suffered a problem of illiquidity.

John W. “Bet‐a‐Million” Gates was the organizer of the secret syndicate that aimed to build upon TC&I and other assets as a competitor to U.S. Steel. He reluctantly agreed to sell his shares in TC&I when he learned that other members of the syndicate had agreed to do so. He moved to Port Arthur, Texas, where he hoped to resume activities in banking, railroads, and other businesses. In 1911 he discovered a cancerous tumor in his throat, which nearly prevented his testimony at the Stanley Committee Hearings on U.S. Steel. Soon thereafter he traveled to Paris, where he hoped that a difficult operation would cure him. It did not. He died there on August 9, 1911, aged 56. The value of his estate was estimated at between $40 million and $50 million.17 In a rather lurid biography, Lloyd Wendt and Herman Kogan wrote, “Gates played as fiercely as any, with a sort of barbaric splendor and freedom from scruples, yet sometimes with a peculiar courage and daring. He was without shame, without many moments of remorse.”18

Grant Schley was the public face of the TC&I ownership syndicate. He sold his shares to U.S. Steel, enabling him to meet collateral calls and weather the Panic of 1907. Upon his death on November 22, 1917, the New York Times said that “he had been in failing health for several years and had not taken an active part in the direction of the affairs of his firm for the last ten years.”19 He had been a member of the NYSE and had served prominent clients in the Standard Oil circle.

Public Servants

Theodore Roosevelt acknowledged that he was “gravely harassed and concerned” over the Panic of 1907.20 He was sensitive to the charges that his policies had triggered the panic and wrote, “I do not think that my policies had anything to do with producing the conditions which brought on the panic; but I do think that very possibly the assaults and exposures which I made, and which were more or less successfully imitated in the several States, have brought on the panic a year or two sooner than would otherwise have been the case. The panic would have been infinitely worse, however, had it been deferred.”21 His other sensitivity about the panic concerned his approval of the Tennessee Coal & Iron acquisition by U.S. Steel. His critics argued that the merger was unnecessary to stem the Panic and that it was a ruse to profit Morgan and his circle. Others complained that Roosevelt’s political philosophy was rather empty. For instance, historian Elting E. Morison wrote, “The Square Deal rests upon no more substantial ground than the intuitive feelings of the executive; a broker who thinks of justice as a satisfactory working agreement.”22

Still, six years later, Roosevelt wrote that his decision on the USS/TC&I deal “offered the only chance for arresting the panic and it did arrest the panic… . The panic was stopped, public confidence in the solvency of the threatened institution being at once restored.”23

Roosevelt was an original item. No previous president offered the combination of massive energy, moral suasion, charisma, and belief in a very strong executive branch. He changed U.S. politics, although, unlike the other faces sculpted into the side of Mount Rushmore, he is remembered more for his style than his substance. Yet his words and policies resonated with the average American, as reflected in his landslide election in 1904 and his significant poll in the 1912 election, as a third‐party candidate.

The biographer H. W. Brands wrote, “The frustrating fact for Roosevelt was that, as much as Americans loved him, they didn’t particularly heed him.”24 After 1908, Roosevelt never regained the “bully pulpit” of powerful elected office. His political influence lay chiefly in the stream of speeches, articles, and books he produced in retirement. His proposal for progressive programs foreshadowed numerous initiatives of presidents later in the twentieth century. After his electoral defeat in 1912, he embarked on a dangerous exploration of the River of Doubt in Brazil that left him weakened from exertion and disease. An ardent advocate for the projection of U.S. power abroad, he reviled Wilson’s policy of neutrality at the outbreak of World War I. When the United States did join the fight in 1917, his four sons volunteered. The youngest boy, Quentin, was killed in 1918, when his airplane was shot down. This plunged Roosevelt into a depression that muted, but did not totally suppress, his public voice. He died on January 6, 1919, in his sleep and was buried at his home, Sagamore Hill, on Oyster Bay, Long Island, New York.

John C. Spooner, who praised J. P. Morgan so lavishly in November 1907, had served in the U.S. Senate for 16 years. Seen by peers as the prominent constitutional authority of his day, he was one of the four powerful committee chairmen who ruled the Senate during the Gilded Age—along with Nelson Aldrich, William Allison, and Orville Pratt. Identified with the “old guard” conservative wing of the Republican Party, Spooner bitterly rejected the progressive impulses of his fellow senator from Wisconsin, Robert La Follette. Although he retired from the Senate in 1907, he remained a political force for years, even declining the offer of a cabinet post as secretary of state in the Taft Administration. Spooner’s retirement from politics along with other powerful senators marked the profound shift in politics and orthodoxy during the 1906–1913 era. After leaving the Senate in 1907, Spooner practiced law in New York City and passed away on June 11, 1919.

Carter Glass, in 1913, succeeded Arsene Pujo as chair of the powerful House Banking and Currency Committee. Then, in 1918, Woodrow Wilson appointed Glass to be the secretary of the Treasury, in which post Glass oversaw the final Victory Loan bond issue after the Armistice. As Treasury secretary, he held a place on the Federal Reserve Board, where he pressured the Fed to maintain low interest rates until the completion of the bond flotation. The Fed’s policies during Glass’s tenure contributed to the wave of inflation after the end of World War I.

From 1920 until 1946, Glass served as U.S. senator from Virginia, ultimately rising to chair of the Senate Appropriations Committee and president pro tempore of the Senate. During the New Deal, Glass co‐sponsored the Glass–Steagall Act of 1933 that divided commercial banks from investment banking and established federal deposit insurance. He also allied with the Southern bloc of legislators who supported states’ rights and Jim Crow segregation. Glass opposed much of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal agenda. He died on May 28, 1946.

In 1927 Glass published a memoir25 of the development of the Federal Reserve Act. The book rebutted assertions about the paternity of the Fed, rejecting a professor’s suggestion that Wilson’s adviser, Colonel E. M. House, had designed the concept of the Federal Reserve System. And the book devoted a chapter to discounting Senator Aldrich’s contributions. Glass acknowledged the contributions of Senator Owen, Secretary McAdoo, William Jennings Bryan, and President Wilson. However, the thrust of the book asserted the leading role he played in the design and passage of the Federal Reserve Act.

Nelson Aldrich served Rhode Island in the U.S. Senate from October 1881 until March 3, 1911, when he retired in declining health. He was committed to tariff protection and the gold standard, pillars of Republican orthodoxy during the Gilded Age. Progressives saw him as an ally of business interests and of the financial community. He died on April 16, 1915, aged 73.

His daughter, Abigail, married John D. Rockefeller, Jr.; their second son was Nelson A. Rockefeller, who served as governor of New York and vice president of the United States. Other descendants included David Rockefeller (chairman of Chase Bank), Richard Aldrich (U.S. representative), Jay Rockefeller (U.S. senator), and Winthrop Rockefeller (governor of Arkansas).

The economic historian Elmus Wicker (2000) argued that Nelson Aldrich had not been adequately recognized in histories of founding the Fed. He said that Aldrich was instrumental in shifting the focus of reform away from debates over asset‐based currency and toward central banking. As a former defender of the old financial orthodoxy, his leadership for change was courageous and decisive. The Aldrich–Vreeland Act provided crucial liquidity during the financial crisis of 1914, a time when the new Fed was not entirely functional. And the Aldrich plan for a central bank offered several provisions that were eventually inserted into the Federal Reserve Act. Wicker wrote, “Carter Glass, the so‐called ‘father’ of the Federal Reserve Act, and Parker Willis, his close associate, went out of their way to repudiate Aldrich’s influence, but it is now becoming increasingly clear that Aldrich deserves equal, if not top billing with Glass as a cofounder of the Federal Reserve System.”26

Robert M. La Follette served Wisconsin in the U.S. Senate from 1906 until the date of his death, June 18, 1925. A staunch progressive, he clashed with conservative Republicans and eventually helped to lead progressives out of the Republican Party. During World War I, he opposed American entry into the war. In 1924, he ran as a third‐party candidate for the White House, advocating nationalization of railroads and electric utilities, affirmation of rights to unionize, income redistribution through taxation, opposition to child labor, and abundant credit provisions to farmers.

Augustus O. Stanley served in the House of Representatives until 1915, as governor of Kentucky from 1915 to 1919, and as U.S. senator from Kentucky until 1925. Stanley’s politics reflected the rickety Democratic Party coalition of the early twentieth century: urban progressives, country populists, organized labor, and Southern segregationists. He fought official corruption, promoted workmen’s compensation, railed against industrial concentration, opposed prohibition of alcohol, and advocated convict labor. However, he opposed bigotry and the Ku Klux Klan, which contributed to his defeat for reelection to the Senate in 1924. Thereafter, he practiced law, and served from 1930 to 1954 on the International Joint Commission that resolved boundary issues between the United States and Canada. He died in Washington, DC on August 12, 1958.

Charles A. Lindbergh, Sr. served five terms in the House of Representatives advocating progressive domestic policies and isolationist stances in foreign affairs. He ran unsuccessfully for the Senate in 1916 and for governor of Minnesota in 1918 and 1924. He died on May 24, 1924, three years before his son made the historic solo flight across the Atlantic.

Arsene Pujo represented Louisiana in the House of Representatives from 1903 until his retirement from politics in 1913. Returning to his hometown, Lake Charles, he practiced law. He died on December 31, 1939, aged 78.

Samuel L. Untermyer, after the conclusion of the Pujo Committee hearings, lobbied unsuccessfully to renew and broaden the investigation. Thereafter, he resumed the practice of law in New York, periodically engaging in federal and state‐level appointments and in Democratic Party initiatives. An active Zionist, he also helped to found the Anti‐Nazi League in 1933, which advocated a boycott of Germany. He died on March 16, 1940, aged 82.

William Gibbs McAdoo served as Secretary of the Treasury in the Wilson administration from 1913 to 1918. Among his boldest acts was to close the New York Stock Exchange at the outbreak of World War I to prevent panicked liquidation of U.S. securities by foreign investors, and generally to retain gold reserves in the United States. In 1914, he married Woodrow Wilson’s daughter. During the war, he also served as director general of Railroads, essentially the leader of the nationalized railroad system. Though a serious candidate for U.S. president in 1920 and 1924, he failed to gain the Democratic Party nomination because of an unwillingness to denounce the Ku Klux Klan, among other reasons. He represented California in the U.S. Senate from 1933 to 1938 and died on February 1, 1941, aged 77.

Robert L. Owen joined the U.S. Senate in 1907, as one of the first two senators from Oklahoma and served until 1925. Active in many progressive causes, he promoted the candidacy of William Jennings Bryan for president, advocated reforms in Native American affairs, sought the reduction of import duties, and criticized the Federal Reserve for its deflationary policies in the 1920s and 1930s. In 1920, he sought unsuccessfully the Democratic Party nomination for president. He passed away on July 19, 1947, aged 91.

Woodrow Wilson’s policies intervened in the private economy more extensively than any predecessor’s—more so than Theodore Roosevelt and Taft, and subsequently eclipsed only by Franklin D. Roosevelt. Progressivism reached its zenith during Wilson’s first term in the White House. He kindled or realized important initiatives in a variety of areas including financial‐sector regulation, the income tax, direct election of senators, lowering the tariff, and strengthening antitrust regulation. During World War I, the executive branch nationalized major sectors of the economy, setting the precedent for extensive central planning during World War II.

Arguably, the Federal Reserve Act was the pinnacle of the Progressive Movement and of Wilson’s first term. It aimed to displace market mechanisms with state direction, personal agency with institutional agency, opacity with transparency, rigid currency with “elastic” money, private oligopoly with government coordination, and concentration of reserves with broad distribution. Consistent with the progressives’ belief in dispassionate research and expertise, oversight of the nation’s money and banking would be placed in a committee of public‐spirited national leaders and experts. What could go wrong? This transformation set a provocative example that would help to inspire the New Deal and Great Society administrations of Franklin D. Roosevelt and Lyndon B. Johnson, respectively.

Seeking to place America on the global stage, Wilson brokered the Versailles Treaty negotiations in 1919 (a plan that John Maynard Keynes famously savaged and that set the stage for global instability in the 1920s and 1930s). Unfortunately for Wilson’s treaty, public sentiment in the United States swung from internationalism to isolationism. Undeterred, Wilson slogged on, ultimately resorting to a whistle‐stop campaign across America to muster public support. During the trip in October 1919, Wilson suffered a debilitating stroke. Absent Wilson’s advocacy, the Senate defeated the Treaty. For the next year, the First Lady and two presidential assistants virtually ran the Wilson administration, a development that eventually prompted adoption in 1967 of the 25th Amendment to the Constitution to provide for official succession in the event of presidential disability. Wilson died on February 3, 1924, at age 67.

Crisis Fighters

George F. Baker rose from president of First National Bank of New York to chairman of the board in 1909, in which role he served until 1926. He died May 2, 1931, at age 91, leaving an estate estimated as high as $500 million ($8.9 billion in 2022 purchasing power). His philanthropy supported 20 universities, 15 hospitals, and 17 New York institutions27 and included a $5 million gift in 1924 to Harvard Business School for the construction of its campus. Upon the announcement of his death, contemporaries during the Panic of 1907 remembered Baker’s leadership—George B. Cortelyou said that “he was always courageous, wise and far‐seeing and therefore a great stabilizing force especially in times of stress and strain.”28

He steadfastly resisted giving interviews to the press until late in life and was called the “Sphinx of Wall Street.”29 He told a reporter, “Business men of America should reduce their talk at least two‐thirds… . Every one should reduce his talk. There is rarely ever a reason good enough for anybody to talk. Silence uses up much less energy. I don’t talk because silence is the secret of success. There, I’ve broken my record. Tell the others they needn’t come in. And get out.”30

Henry P. Davison became a senior partner at J. P. Morgan & Company in 1909. In testimony at the Pujo hearings, Davison was one of the most articulate defenders of bankers as stewards of the public interest. Davison argued that the banker should be a director of corporations because of

… his moral responsibility as sponsor for the corporation’s securities, to keep an eye upon its policies and to protect the interests of investors in the securities of that corporation … in general [bankers] enter only those boards which the opinion of the investing public requires them to enter, as evidence of good faith that they are willing to have their names publicly associated with the management.31

In August 1914, Davison persuaded the governments of France and Britain to grant J. P. Morgan & Company a monopoly franchise on underwriting bonds issued by those governments in the United States. During World War I, he raised funds for the American Red Cross to supply ambulances to the American Army in France. He pressed for the formation of the International Red Cross, an association of the national Red Cross organizations, a goal that was achieved in 1919. Following two unsuccessful operations to excise a brain tumor, he died in 1922 at the age of 55.

George W. Perkins retired from J. P. Morgan & Company in 1910 at the age of 48. His early retirement was described by his family as a desire to “devote most of his time to public work.”32 He worked for Theodore Roosevelt’s presidential campaign in 1912 and continued as a political adviser thereafter. During World War I, he worked to organize food supplies for the army and assisted the YMCA in raising money for relief work among soldiers. He also raised funds to create Palisades Park. Thereafter he subsided from public view, a remarkable change for one of the most creative and effective players in the New York financial community. Perkins had been a major architect of the combinations that created International Harvester and U.S. Steel, and had lifted New York Life Insurance Company to the top echelon of its industry by daringly eliminating intermediaries in the distribution of life insurance services in the United States.

Perkins died June 18, 1920, following a nervous breakdown in May. Papers reported that he contracted influenza in France and had not fully recovered when he resumed work. The New York Tribune said that he died from “acute inflammation of the brain, the result of complete nervous exhaustion due to intense and continuous overwork.”33

James Stillman was president of National City Bank from 1891 to 1909 and chairman of the board from 1909 to 1919. A biographer described Stillman as a

carefully‐dressed, smallish man, with the tall hat and the inevitable cigar, who didn’t answer sometimes for twenty minutes, but fixed one with his clear, dark eyes and his air of immense dignity, presented a really fascinating enigma. His mental power was as great as his shyness and, like many shy people who inspire fear in others, he preferred those who were not afraid of him… . Throughout his day’s work, there was manifest intensity visible in the concentration, in the careful calculation of each problem, in the dislike of hearing any details discussed, while yet expecting them to be carefully watched.34

Stillman foresaw the massive economic changes in America and positioned the bank to serve them. He envisioned that National City Bank would provide “any service” that the modern large corporations would require. In February 1907, Stillman wrote:

I firmly believe … That the most successful banks will be the ones that can do something else than the mere receiving and loaning of money. That does not require a very high order of ability but devising methods of serving people and [of] attracting business without resorting to unconservative or unprofitable methods, that opens limited fields for study, ability and resourcefulness and few only will be found to do it.35

Thereafter, National City Bank broadened its range of services, expanded its service to institutions and individuals, and reached to new locations. Stillman implemented a decentralized, multidivisional structure. Historians Harold Cleveland and Thomas Huertas have argued that by the start of the twentieth century, National City was a truly “modern” corporation, a leading firm in its industry. Stillman died, still chairman, in March 1918. In 1955, National City Bank merged with First National Bank of New York to form Citibank, forerunner of Citigroup, one of the largest American financial institutions in the early twenty‐first century.

Benjamin Strong rose to president of Bankers Trust and served in that capacity until 1914, when he was appointed the first governor of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. He served in that capacity until October 1928, when he died at age 55 of an intestinal abscess. He was the “prime mover … dominant figure” of the Federal Reserve System from its inception, said Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz.36 He had grasped the need for international coordination to assist Europe’s recovery from World War I and was a leading proponent of “easy money” policies that drove the boom in the stock market in the 1920s and its eventual reckoning in 1929.37

In a note to another governor written shortly before his death, Strong advocated aggressive use of open market operations to flood the market with liquidity in the event of another financial crisis. Unfortunately, Strong’s successors ignored the advice and for three years pursued deflationary policies with disastrous effect. Economists Friedman and Schwartz attributed the severity of the Great Depression to “the shift of power within the System and the lack of understanding and experience of the individuals to whom the power shifted.”38 The Wall Street Journal eulogized him: “His services were of the highest value and conditions today might have been different if his health had permitted undivided attention to his office for the past three months.”39

Frank A. Vanderlip worked for National City Bank from 1904 until 1919. His most important contribution to the aftermath of the Panic of 1907 was to be the ghostwriter of the “Aldrich Plan,” in which he drafted proposed legislation to establish the modern Federal Reserve System.40 Vanderlip rose to president of National City Bank in 1909. His important innovation was the founding of the first foreign branch in Buenos Aires—this was the first foreign branch for any U.S. national bank. He also led the organizing of American International Corporation in November 1915, an investment trust intended to funnel American capital to foreign projects and companies. Vanderlip chafed under Stillman’s voting control of National City Bank and sought from Stillman an option to buy his shares. Stillman refused. Poor in health, Stillman spent much of 1917 in Paris.

Vanderlip continued to promote the internationalization of the bank and made the unfortunate decision to open a branch in Moscow, just after the Russian Revolution. The branch’s assets were soon nationalized, leaving National City Bank exposed to repay deposits in that branch from dollars in New York—an exposure equal to 40 percent of the bank’s capital. Stillman returned to New York, placed Vanderlip on leave, and died soon thereafter. Control of the bank passed to Stillman’s son. Vanderlip resigned in June 1919.41 Stillman’s son proved to be an incompetent executive and resigned in May 1921, turning management of the company over to a new cohort of professional executives who demanded, and were given, an equity interest in the bank. Frank Vanderlip died on June 29, 1927.

Thomas W. Lamont stayed with J. P. Morgan & Company for his entire career, becoming a partner in 1910 and rising to the position of chairman of the board in 1943. He was acting head of the firm on “Black Thursday,” October 24, 1929, when he committed the company to large purchases of stocks in an effort to instill confidence in the market. He served on various semiofficial assignments for the U.S. government, including the 1919 Paris Peace Negotiations that led to the Treaty of Versailles. He died on February 2, 1948. His son, Corliss Lamont, was a philosophy professor at Columbia and a socialist. His other son, Thomas Stillwell Lamont, rose to vice chairman of Morgan Guaranty Trust Company. His grandson, Ned Lamont, was the antiwar candidate for U.S. Senate in Connecticut in 2006.

J. P. “Jack” Morgan Jr. arrived in Europe at the height of the Panic to assist his father with the attempt to arrange gold loans from the central bank of France to U.S. banks. The French, concerned about the deepening crisis, insisted on a guarantee of the loan from the U.S. government. Roosevelt refused on grounds that this would set the precedent for government guarantees of private deals. Eventually, Jack’s negotiations led to gold imports from European sources. Jack was back in the United States by January 1908. He worked in the shadow of his famous father and the luminous financiers at J. P. Morgan & Company, such as George Perkins, Henry Davison, and Thomas Lamont. Jack’s work at the firm proceeded quietly. In 1910, he was active in organizing the London affiliate, Morgan, Grenfell. Later that year, he sustained a partial nervous breakdown that removed him from business for some months. (Like his father, Jack suffered bouts of “the blues,” as he called them.)

Jack followed the build‐up to the Pujo hearings and then coached his father in preparing to testify. Upon Pierpont’s death in 1913, Jack became the senior partner of the firm. The firm won the mandate as sole financier for French and British purchases in the United States during World War I. In 1915, a German sympathizer attempted to assassinate Jack, almost killing him with two shots in the abdomen. This generated popular sympathy for him. Upon his return to work, a crowd gathered to applaud. In the following years, he assisted the war effort, helped to reorganize General Motors, financed corporate growth in the 1920s, reorganized J. P. Morgan & Company in the 1930s, and rationalized his father’s massive art collection. Though he was a senior partner of the firm, Jack relied increasingly upon Thomas W. Lamont as, in effect, chief executive. Jack died of a heart attack on March 13, 1943, at the age of 75. His biographer, John Forbes, said, “Morgan was a team player and submerged his own personality in the firm, where he managed with consummate skill to hold together a group of highly skilled and individualistic partners and make maximum use of their separate gifts to achieve very substantial results.”42

Paul Warburg, after passage of the Federal Reserve Act in 1913, continued to advise on monetary matters, while working as an investment banker at Kuhn, Loeb. He accepted appointment to the first group of governors of the Federal Reserve, serving as a governor from 1914 to 1918. And then from 1916 to 1918, he served as vice chair of the Federal Reserve Board. He passed away on January 24, 1932, at the age of 63.

Arguably, Warburg was the intellectual locomotive of the movement toward a central bank. His early proposals for a central bank formed the core of the Jekyll Island plan and of Nelson Aldrich’s proposal for a National Reserve Association. Even the Federal Reserve Act retained elements of his ideas. Certainly, his ceaseless advocacy before, during, and after the Panic of 1907 helped to drive the monumental shift in economic orthodoxy toward central banking. His two‐volume memoir about the origin and growth of the Federal Reserve system, published in 1930, continued that advocacy, especially for centralization of the system and for control by experts who understood banking. The undercurrent of the memoir is a lament about the distortions of good ideas by ill‐informed and inexpert politicians.

George B. Cortelyou remained as Secretary of the Treasury until the end of the Roosevelt administration in 1908. During the early jockeying of successors to Roosevelt, Cortelyou emerged as a potential candidate, only to be stopped when Roosevelt endorsed Taft. In January 1908, rumors circulated that Cortelyou was to be named president of the resurrected Knickerbocker Trust Company—until he disavowed his interest in the position. He threw his support behind the concept of a central bank for the United States, because, based on his experience, the Treasury did not have the power to maintain stability of the financial system during a crisis. Failing to win an appointment in the Taft administration, he left the public sector. On January 13, 1909, the New York Times reported that he would become the chief executive officer of Consolidated Gas Company, headquartered in New York City. He died on October 23, 1940, in New York.

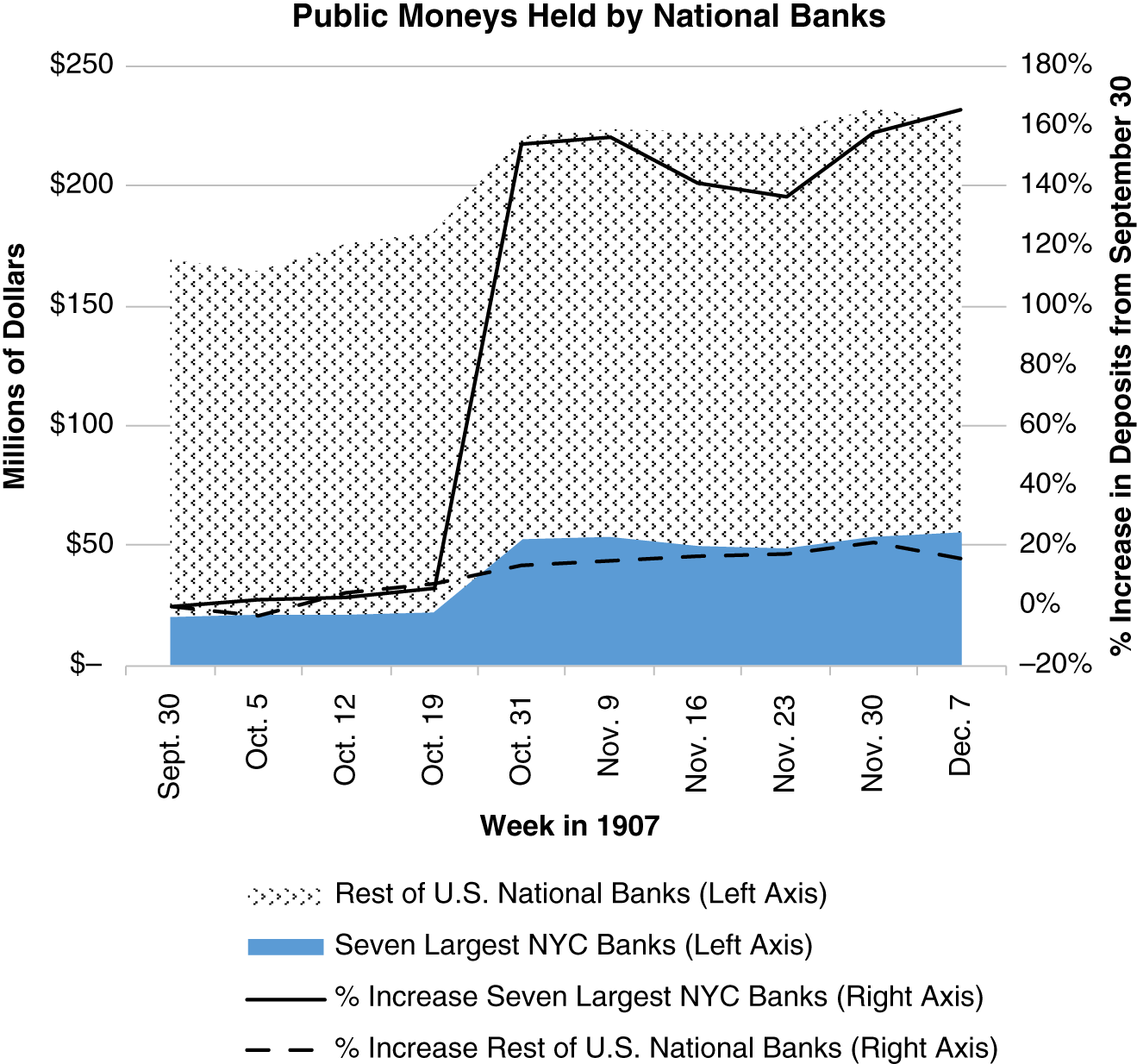

The newspaper headlines, memoirs, and other accounts of the Panic of 1907 seem to relegate Cortelyou to subordinate status as a crisis fighter. This is unfortunate. Figure 23.1 shows that on short notice, Cortelyou deposited between $54 million and $64 million in cash into the national banks across the nation, of which a maximum of $34 million went to seven large New York banks.43 The asymmetry of how the deposits were distributed became a lightning rod of Congressional criticism for Cortelyou after the Panic.

Figure 23.1 Time Series of the Stock of U.S. Treasury Deposits of Public Funds in National Banks During the Panic

NOTE: The lines in this figure indicate the cumulative percentage change in deposits from September 30 to the date indicated. The shaded areas indicate the balance of deposits at each date.

SOURCE: Authors’ figure, based on data in Response of the Secretary of the Treasury to Senate Resolution No. 33 of December 12, 1907, January 29, 1908, Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, pp. 37–72.

The point is that Cortelyou mobilized such a large amount of money that it rendered him a major player during the crisis. Moen and Rodgers report that J. P. Morgan directed the deployment of about $96 million in facilities, to which his firm contributed as much as $50 million or as little as $1.5 million.44 Research has yet to reveal whether and to what extent funds Morgan and his circle deployed were supplied by Cortelyou. But based on gross commitments, it appears that Cortelyou and Morgan deployed funds of a similar order of magnitude.

What may matter more than the size of rescue funds was the impact they achieved. Jon Moen and Mary Tone Rodgers note “[p]erhaps the timing of Morgan’s facilities was more important than their sizes because they occurred near the beginning of the crisis, thus blunting contagion early on.”45 And as this narrative shows, the focus of Morgan’s facilities was targeted toward particular rescues, serving as a lender of last resort on the spot at the center of the crisis.

In contrast, Cortelyou briefly visited New York City during the crisis and generally deployed funds from Washington, DC, to national banks across the country (but predominantly in New York), which he expected would reliquefy the financial system and direct funds to best use. And his proposed offering of Panama Canal bonds and 3 percent Notes in November enabled banks to expand the volume of banknotes in circulation, although in the final event this scheme had only marginal impact. Finally, Cortelyou’s public expressions of confidence lent the weight of the federal government to the effort of redirecting public sentiment from fear to recovery. Cortelyou genuinely earned the praise he received as a crisis fighter.

In short, Cortelyou and Morgan played crucial but different roles in the Panic. Both deserved recognition for their significant efforts.

J. Pierpont Morgan emerged from the Panic of 1907 lauded by some and hated by others even more than before. Letters and cables of congratulations for his leadership poured in. He and his firm enjoyed a robust volume of corporate financing business buoyed by his reputation in the crisis. In 1910, Harvard granted him an honorary doctorate. By 1912, he was withdrawing seriously from daily business to focus on philanthropy and his beloved collection of books and art.

The panic had inflamed the longstanding belief among progressives that Morgan’s success was due to anticompetitive behavior. Morgan, the organizer of large corporate combinations, was famous for combating “ruinous competition.” Thus, the Pujo hearings, nominally covering the structure of corporate finance in America, was focused particularly on J. P. Morgan & Company, and its senior partner, Pierpont.

He left for Europe on January 7, 1913, shortly after giving testimony in the Pujo hearings. Touring through Egypt, he fell ill on February 13 with what his doctor said was “general physical and nervous exhaustion resulting from prolonged excessive strain in elderly subject.”46 Pierpont died in Rome on March 31, 1913, aged 75. Thomas Lamont wrote that the effect of the Pujo hearings “upon Mr. Morgan’s physical powers was devastating.”47

Without question, Morgan had promoted industrial consolidation throughout the Gilded Age, which earned the progressives’ and populists’ scorn for monopolization (or “Morganization,” as some called it). His wealth, trips to Europe, and art collecting sharpened public concerns about economic inequality. His push for industrial consolidation was motivated by economic gain. Yet his words and deeds are also consistent with a desire to improve the performance of businesses whose securities he underwrote. He saw that technological innovation during the Second Industrial Revolution would yield new economies of scale and scope, if managed well. As the leading channel of foreign direct investment into the booming American economy, he stewarded the interests of foreign (and domestic) investors. It was a risky age for investors, before Generally Accepted Accounting Principles, public accounting, and federal regulations of markets, securities, corporations, and financial institutions. Displacing corrupt and incompetent management, shutting down inefficient operations, and rationalizing industries, Morgan disciplined the business economy to yield performance that investors—and society—needed.

In 1907, Morgan was not the only notable crisis fighter. Cortelyou and the New York Clearing House played important roles as well. But Morgan’s signal contributions were to recognize threats to systemic stability before others and quickly to galvanize collective action among bankers in a targeted way. A study of lender‐of‐last‐resort rescues by various actors during the Panic by Jon Moen and Mary Tone Rodgers found that Morgan’s “individual LOLR efforts may have been distinguishable from institutional efforts by the Clearing House and the U.S. Treasury.”48 They ascribed Morgan’s success to his reputation as an informed market agent, a source of valuable advice and rescue loans, and his experience in dealing with earlier crises. Morgan demonstrated an ability to mobilize his social and financial network in ways that others apparently could not. Quite simply, he took action, persuaded others to do so, too, and had an effective impact.

Morgan’s leadership during the Panic of 1907 is of a piece with his values of stewardship and industrial stability. There is no question that throughout the Panic his firm earned interest on rescue loans (they were not gifts), that systemic stability aligned with his business interests, and that adversaries (Charles Barney and Charles Morse) suffered. But archives have yet to yield direct evidence that, as La Follette, Heinze, Lefèvre, and others claimed, Morgan and his associates engineered the panic for their own benefit with the intention of crushing adversaries—this claim warrants further research. So do the decisions by National Bank of Commerce, the NYCH, and Morgan not to support the Knickerbocker Trust Company. However, the preponderance of Morgan’s leadership during the Panic is more consistent with stewardship for the public good than mere personal gain. To acknowledge that is less to elevate J. Pierpont Morgan to the status of a hero, and more to affirm the importance of human agency in business and economic affairs.

Notes

- 1. The dollar value of deposits in the Knickerbocker Trust Company of $47 million was expressed in a statement by Herbert L. Satterlee in December 1907 and quoted in “Knickerbocker Trust Co.: Herbert L. Satterlee Speaks of Necessity of Cooperation by Depositors to Reopen Institution,” New York Times, December 21, 1907, p. 8.

- 2. Sprague (1910, p. 251), Hansen (2014, pp. 556–557) and others have implied that the Knickerbocker was solvent but illiquid in arguments that Morgan used the crisis to discipline the trust companies.

- 3. “Joy at the Opening of Knickerbocker,” New York Times, March 27, 1908, p. 6.

- 4. From 21,986 commercial and mutual savings banks, the number declined to 7,219 commercial banks at the end of 2007. See Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (US) and Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Commercial Banks in the U.S. (DISCONTINUED) [USNUM], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/USNUM, July 8, 2022. Also see U.S. Bureau of the Census, Historical Statistics of the United States: Colonial Times to 1970 (Washington, DC: Department of Commerce, 1975), Part 2, Series X580‐587, p. 1019.

- 5. Dean Corbae and Pablo D’Erasmo, “Rising Bank Concentration,” March 2020, Staff Report No. 594, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis.

- 6. See Silber (2007) for details on the closing of the NYSE in 1914.

- 7. See Gage (2006) for details on the anarchist bombing at 23 Wall Street in 1920.

- 8. Manuscript of “The Life of F. Augustus Heinze,” by Otto Heinze (1943), p. 62. Found among the papers of Sarah McNelis, Heinze’s biographer.

- 9. New York Evening World, May 27, 1909, quoted in Reveille, May 28, 1909 and by McNelis (1968), p. 170.

- 10. McNelis (1968), p. 168.

- 11. Ibid., p. 183.

- 12. David Fettig (ed.), F. Augustus Heinze of Montana and the Panic of 1907 (Federal Reserve of Minneapolis, 1989); also, New York Times, May 15, 1909, and November 5, 1914.

- 13. McNelis (1968), p. 184.

- 14. Zuckoff (2005), p. 49.

- 15. Details about Morse are drawn from Zuckoff (2005), pp. 49, 50.

- 16. Details about Morse after his return from Europe are drawn from Pringle (1939). Downloaded from www.doctorzebra.com/prez/z_x27morse_g.htm#zree16.

- 17. Wendt and Kogan (1948), p. 329.

- 18. Ibid., p. 331.

- 19. “Grant B. Schley, Financier, Dead: Head of Firm of Moore & Schley and Member of Stock Exchange for 36 Years; In Many Big Operations,” New York Times, November 23, 1917, p. 11.

- 20. Letter to Douglas Robinson, November 16, 1907, excerpted in Hart and Ferleger (1941), p. 410.

- 21. Letter to Hamlin Garland, November 23, 1907, excerpted in Hart and Ferleger (1941), p. 411.

- 22. Elting E. Morison, “Introduction,” in Morison, Blum, Chandler, and Rice (1952), Vol. 5, p. vii.

- 23. Quoted in Hart and Ferleger (1941), p. 607.

- 24. Brands (1997), p. 812.

- 25. Glass (1927).

- 26. Wicker (2005), p. 5.

- 27. Lopez (undated), “A Tarnished Legacy: George Fisher Baker, U.S. Steel, Convict Leasing and Columbia Athletics,” Columbia University, downloaded August 17, 2022 from https://columbiaandslavery.columbia.edu/content/tarnished-legacy-george-fisher-baker-us-steel-convict-leasing-and-columbia-athletics.

- 28. “Leaders in Nation Eulogize Baker: Bankers Call Him ‘Mentor’ and Praise His Integrity and Unostentatious Charity,” New York Times, May 3, 1931, p. 28.

- 29. “George F. Baker, 91, Dies Suddenly of Pneumonia; Dean of Nation’s Bankers,” New York Times, May 3, 1931, p. 1.

- 30. “Baker Was a Power in World Finance: With Elder Morgan and James A. Stillman, He Dominated Vast Network of Companies,” New York Times, May 3, 1931, p. 28.

- 31. De Long (1991), p. 15, quoting Davison, Henry, (1913), Letter from Messrs. J.P. Morgan and Co. in Response to the Invitation of the Sub‐Committee (Hon. A.P. Pujo, Chairman) of the Committee on Banking and Currency of the House of Representatives, New York [Harvard Graduate School of Business Baker Library, Thomas W. Lamont Papers, Box 210‐26].

- 32. Quotation from George W. Perkins Collection, General File, Obituaries 1920. Box 18, Rare Books and Manuscripts, Butler Library, Columbia University.

- 33. New York Tribune, June 19, 1920, p. 4.

- 34. Burr (1927), p. 97.

- 35. Quotation of Stillman from Huertas (1985), pp. 147–148. Originally drawn from James Stillman, letter to Frank A. Vanderlip, February 12, 1907, Vanderlip MSS, Columbia University.

- 36. Friedman and Schwartz (1963), p. 411.

- 37. Roberts (2000), p. 13: “Strong’s ‘easy money’ policies designed to assist Britain’s return to the gold standard produced a speculative rise in stock prices on the New York Stock Exchange. But this picture hardly fits the Benjamin Strong who, in his support of the fateful decision in 1928 to raise interest rates and force a monetary contraction to bring down stock prices, was an economic nationalist. High interest rates in the United States pulled capital out of Europe and forced monetary deflation there and elsewhere. The international gold standard that Strong had labored so hard to create became an engine of worldwide deflation.”

- 38. Friedman and Schwartz (1963), p. 411.

- 39. Quotation of Wall Street Journal on Benjamin Strong given in Time magazine article, October 29, 1928. Downloaded from www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,928986,00.html.

- 40. Vanderlip’s leadership in the design of the Federal Reserve System is discussed in chapter 2 of Primm (1989).

- 41. Details of Vanderlip’s relations with Stillman are drawn from Huertas (1985).

- 42. Forbes (1981), p. x.

- 43. Cortelyou’s Response of the Secretary of the Treasury to Senate Resolution No. 33 (1908) does not simply state the total amount of funds he distributed. Indeed, the Response suggests various amounts. Figure 23.1 is derived from pages 37–72 of the Response that details public moneys deposited in national banks by week during the crisis. Other details in the Response suggest a range from $79.8 million (increase in public deposits, p. 14) to $103 million (the difference between all deposits in national banks on December 31, 1907 of $246 million (p. 31) and all deposits in national banks of $143 million on August 22 (p. 23)). Some of this variation is due to differences in the length of the measurement period.

- 44. Moen and Rodgers (2022), pp. 22–23.

- 45. Ibid., p. 23.

- 46. Quotation of Morgan’s illness given in Forbes (1981), p. 72.

- 47. Quotation of Thomas Lamont given in Forbes (1981), p. 74. Source of quotation is a letter from T. W. Lamont to H. S. Commager, March 17, 1938, Partners file, J. P. Morgan Jr. Papers.

- 48. Moen and Rodgers (2022), p. 24.