Chapter 15

A City in Trouble

A millionaire is wicked, quite;

His doom should quick be knelled;

He should not be allowed to grow,

If grown he should be felled,

But when a city’s bonds fall flat

And no one cares for them,

Who is the man who saves the day?

It’s J.P.M.

When banks and trusts go crashing down

From credit’s sullied name,

While speechifying Greatness adds

More fuel to the flame,

When Titan strength is needed sore,

Black ruin’s tide to stem,

Who is the man who does the job?

It’s J.P.M.

—McLandburgh Wilson, New York Times, October 27, 1907

Criticism and Praise

During the early stage of the financial crisis, Theodore Roosevelt was on a hunting expedition in the canebrakes of Louisiana. (Upon his return, the New York Times quipped that “he had added several deeper shades to the bronze acquired during the Summer months at Oyster Bay.”1) The president’s first utterance about the Panic was on Tuesday, October 22, en route to Washington. He stopped in Nashville, Tennessee, where in an impromptu speech he insisted that his policies had not caused the panic. In his remarks, he made the stock speculator the focus of his ire, saying,

[The speculator] is doing all that he can to bring down in ruin the fabric of our institutions, and it is our business to set our faces like flint against his wrongdoing, to war to undo that wrongdoing in the interest of the people as a whole, and primarily in the interests of the honest man of means.2

Within two days of making that statement, however, Secretary Cortelyou had advised Roosevelt to offer a less belligerent message to the public. On October 25, President Roosevelt wrote the following note to Cortelyou with instructions to have it published:

I congratulate you upon the admirable way in which you have handled the present crisis. I congratulate also those conservative and substantial businessmen who in this crisis have acted with such wisdom and public spirit. By their action they did invaluable service in checking the panic which, beginning as a matter of speculation, was threatening to destroy the confidence and credit necessary to the conduct of legitimate business. No one who considers calmly can question that the underlying conditions which make up our financial and industrial well‐being are essentially sound and honest. …The action taken by you and by the businessmen in question has been of the utmost consequence and has secured opportunity for the calm consideration which must inevitably produce entire confidence in our business conditions.3

A regularity of financial crises before and since 1907 has been the utterance of calming bromides by national leaders, regardless of how realistic or well‐informed. As of October 25, the crisis was far from quelled and its impact on the real economy had even longer to run. Nevertheless, J. P. Morgan must have taken some degree of satisfaction in his apparent vindication by the president.

When the Stock Exchange opened for its regular, short day of trading on Saturday morning, October 26, the atmosphere remained tense. However, since the markets would close at noon and money could be neither called nor loaned on Saturdays, there was an incipient sense of calm. In part, the morning papers had provided the palliative that Morgan’s public relations campaign had been intended to achieve. The New York Times quoted financier Jacob H. Schiff, head of the banking firm Kuhn, Loeb & Company, who praised the actions of both Morgan and Cortelyou. “We are doing everything we can to support the heroic efforts of Mr. J. P. Morgan to strengthen the banking situation generally,” Schiff said. “The prompt, decisive, and effective course of the Secretary of the Treasury deserves unstinted praise, and all must seek in every way to aid in allaying needless alarm which has sprung up and which, I believe, is already subsiding.”4 Industrialist Andrew Carnegie also heralded Morgan’s work and admonished depositors to have courage. “Above all, let no man or woman selfishly lock their hoardings in private security,” Carnegie said, “but let them bring forth their surplus and add it to the public exchequer, so as to relieve the present famine in the money market.”5

Across the Atlantic, further encouragement was heard as well. The papers printed a tribute to Morgan from Britain’s Lord Rothschild, who remarked on his “admiration and respect” for the American financier.6 A French manufacturer said, “So great is the confidence of the great French bankers in Mr. Morgan and Mr. Stillman personally, that were they to come to France tomorrow they could find $100,000,000 gold without the slightest difficulty.”7 A banker from Germany added, “We are telling our customers that it is our duty to uphold the sound American industrial situation, and heavy buying orders are resulting.”8 While the international financial community was genuinely supportive of the situation in the United States, clearly they also saw an opportunity for profiting from the severely depressed prices of American securities.

New York Stress: Meeting the Calls of Country Banks

The week ending October 25 had delivered an enormous blow to the New York financial community. Country bankers who had placed their surplus reserves with New York institutions now wanted them back. The trigger was obvious: the suspension of the Knickerbocker and runs at the Trust Company of America, Lincoln, and others fed fears that the bankers’ deposits would be lost or tied up in an endless bankruptcy resolution process. This commenced a financial drain on the New York institutions that would not return to normal until January. Figure 15.1 compares the weekly cash flows from New York to the interior in 1907 to the average of the four previous years. The sharp drop in the week ending October 25 was a harbinger of financial strain on New York.

Figure 15.1 Flows of Cash from New York to the Interior

NOTE: Negative values indicate outflows from New York to the interior; positive values indicate inflows.

SOURCE: Authors’ figure, based on data given in “Money: Sharp Decline in Cash Loss to the Interior,” New York Times, December 16, 1907, p. 8.

Shipments of gold to the interior stressed the New York banks. Secretary Cortelyou later wrote, “more than the entire net loss in [nationwide] national‐bank reserves fell upon the national banks of New York City.”9 Cortelyou employed this fact to defend his decision to bestow the early government deposits on New York national banks. As the Panic spread, he widened the geographic range of the government deposits. As of December 31, Cortelyou estimated that about $246 million in government deposits were held in U.S. national banks across the country, up from $143 million on August 22.10

Hoarding

A second major source of stress on the financial system was the disappearance of cash. Perkins reported that a large part of the money that Secretary Cortelyou had disbursed to the banks and which, in turn, had been handed over to depositors had since been locked up in safe deposit vaults. Perkins learned that nearly 2,000 new safe deposit boxes had been rented in New York City since Monday morning. Stories circulated about depositors locking up their cash or taking it home.

Figure 15.2 presents the time trend of rentals of new safe deposit boxes in five reserve cities. New York peaked exactly at the weekend of greatest stress, when the Stock Exchange nearly closed and when banks decided to issue loan certificates. Other cities peaked shortly thereafter. Hoarding behavior suggested that the last week of October and the first two weeks of November were the climax of the crisis.

All told, during the panic about $350 million in deposits were withdrawn from the U.S. financial system.11 Of this amount, the bulk of it was simply socked away: stuffed under the mattress or the hearthstone. Estimates of funds hoarded ranged from $200 million to $296 million,12 or about 17 percent13 of all the currency in circulation in 1907. Pierpont Morgan issued a statement to the press:

I cannot too strongly emphasize the importance of the people realizing that the greatest injury that can be done to the present situation is the thoughtless withdrawal of funds from banks and trust companies and then hoarding the cash in safe deposit vaults or elsewhere, thus withdrawing the supply of capital always needed in such emergencies as that with which we have been confronted during the last week.14

Figure 15.2 Trends in the Rentals of New Safe Deposit Boxes in Five Major U.S. Cities

SOURCE: Author’s figure, based on data in Andrew (1908a), p. 294.

Imported Gold and More Treasury Deposits

One solution to the hoarding and shipments to the interior was to get more gold into circulation. Morgan and his associates received word by cable on Saturday morning that $3 million of gold was en route to New York from London. The news could not have come at a more propitious moment.

Also, Treasury Secretary Cortelyou directed more government money to be deposited at banks. On Saturday, October 26, another $1.8 million in gold and $185,000 in silver dollars were removed from the Subtreasury’s vaults and taken to various banks in the city. Meanwhile, several tons of silver and gold and bales of paper money arrived on Saturday from Washington, mostly of small currency, with another shipment expected by Sunday.

Unfortunately, in their weekly report on Saturday, the New York national banks reported a loss of $12.9 million in cash, which was accounted for partly by the shipments of currency to the interior and the increase in loans to other institutions needing ready money. Given the nation’s dwindling currency in circulation, the news of the gold shipments and Treasury deposits, which were reported immediately by Morgan’s committee to the ticker agencies, heartened both investors and depositors throughout the city. For the entire month of November, banks would import $68 million in gold,15 facilitated in part by the efforts of J.P. Morgan’s son, “Jack,” who was in Paris.16

Figure 15.3 documents the strain that the NYCH members faced at the end of October. Between October 1 and early November, the gold reserves of the NYCH banks fell by a quarter and the surplus reserves (those in excess of the federally mandated minimum reserve) fell into a deep deficit. Gold imports helped to offset the declining balance of gold and reserves at the banks.

Figure 15.3 NYCH Reserves and Specie Balance Compared to Net Gold Imports

SOURCE: Authors’ figure, based on data in Rodgers and Wilson (2011), pp. 169–170.

The figure reveals a dramatic decline in surplus reserves and specie balance among the NYCH member banks beginning in the last week of October, just after the Knickerbocker’s suspension. Weekly imports of gold helped to meet the withdrawals of depositors, although the figure suggests that the gold imports—and additional deposits from the U.S. Treasury—were simply passed through the NYCH members. After mid‐December, gold imports and the return of deposits from the interior and from hoarders began to restore the surplus reserves.

NYCH Issues Clearing House Loan Certificates

Another response to the financial strain on the banking system was to issue substitutes for legal tender currency, particularly clearing house loan certificates. On October 26, the New York Clearing House (NYCH) took this step, one of the pivotal events of the Panic of 1907.

During previous financial crises, such as in 1873, 1884, 1890, and 1893, the NYCH had resorted to issuing temporary, emergency loans to its member banks in the form of clearing house certificates. The banks had substituted these certificates for currency when clearing accounts with one another at the clearing house each day. Since the certificates circulated among member banks as a substitute for cash, they effectively freed up actual cash for the public, thereby artificially expanding the nation’s money supply. Without a central bank to provide this function, the certificates proved to be extremely effective at restoring liquidity to the financial system during critical periods of stringency. However, the issuances of these certificates were ad hoc, and they often indicated a desperate, last‐resort attempt to address a deepening, systemic crisis.

At various times during the preceding week, the use of clearing house certificates had been suggested in New York, especially during the conferences of the clearing house member banks. Morgan, however, had steadfastly opposed the idea of using them, convinced that their issuance would only signal deeper trouble. He was adamant about avoiding any measures that could further frighten the public. In addition, one can imagine the complex dynamic within the clearing house membership—some bankers might resist suspending convertibility on moral grounds, believing that if they have the resources, they should give depositors their cash. More darkly, delay might serve the interests of strong banks that wanted to discipline the weaker banks—as historian Elmus Wicker has argued, such behavior represented a conflict of private interest over the public interest.17

Having already weathered the raging storm for two weeks, the financiers were left with few other options than to issue clearing house certificates. Bank clearing houses in Chicago, Pittsburgh, and Philadelphia, in fact, had already proposed using certificates. On October 26, the 53 member banks of the NYCH decided to issue $100 million of certificates to be available on Monday, October 28, providing much‐needed liquidity for the system.

At a later meeting of the NYCH banks, it was determined that each of the banks would provide securities to the clearing house as collateral for the certificates, which would be issued for up to 75 percent of the value of these securities. Interest charged on the certificates would be a standard 6 percent. As an additional means of freeing up currency, the bankers urged that the trust companies should thereafter use certified checks (i.e., checks certified by clearing house member banks) in lieu of cash to pay any depositor withdrawals. Furthermore, the clearing house also discussed the possibility of admitting the trust companies as members, with a 15 percent reserve requirement. The bankers were reported to be generally in favor of this measure, particularly if it would include a system of inspection and examination for the trusts.

The NYCH’s suspension of convertibility of deposits and issuance of clearing house loan certificates immediately prompted clearing houses in other cities to suspend as well. Nevertheless, the issues of loan certificates occurred in the greatest volume in major metropolitan areas.

Figure 15.4 presents the growth of clearing house loan certificates outstanding. Two insights emerge from the figure. First, the issuance of certificates spread rapidly—almost contagion‐like. Over three days, the total volume had reached $200 million, almost all of what would ultimately be issued.18

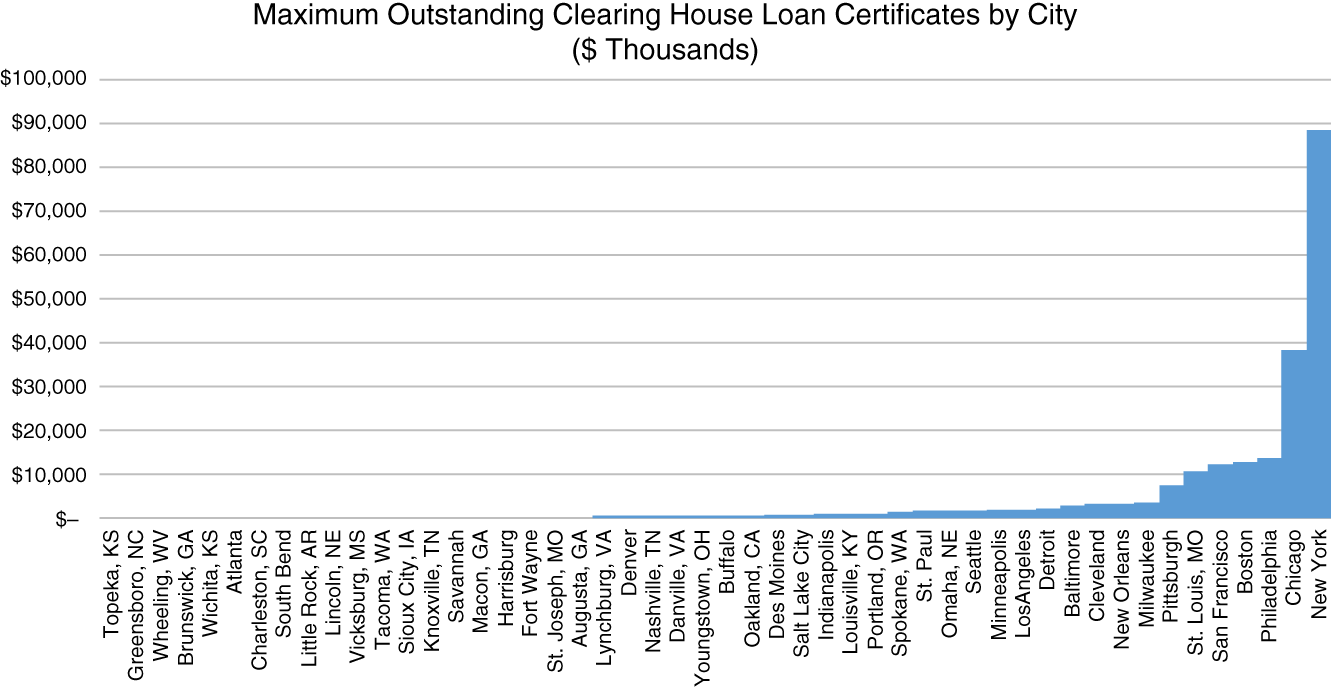

Second, the bulk of the certificates was issued in major metropolitan areas. Figure 15.5 presents the distribution of outstandings by city, ranked from smallest to largest.

Figure 15.4 Cumulative Growth of the Adoption of Clearing House Loan Certificates and Other Currency Substitutes Across 50 American Cities

SOURCE: Authors’ figure, based on data in the Annual Report of the Comptroller of the Currency (1908), pp. 65–66.

Figure 15.5 Distribution of Maximum Outstanding Clearing House Loan Certificates by City, October–November 1907

SOURCE: Authors’ figure, based on data in the Annual Report of the Comptroller of the Currency (1908), pp. 65–66.

Six cities accounted for $175 million of the $219 million cumulative total clearing house loan certificates outstanding: New York ($88.4 million), Chicago ($38.3), Philadelphia ($13.5), Boston ($12.6), San Francisco ($12.3), and St. Louis ($10.6)—these all were “reserve cities” to where country bankers would send their surplus reserves to earn interest. Clearing houses in 13 other cities issued certificates between $1 million and $10 million. The other 31 clearing houses issued certificates in small volume. The median outstanding across the 50 cities was $544,000.

Currency Premium Widens

Currency substitutes (such as clearing house loan certificates, cashier’s checks, and corporate IOUs of various kinds) began to trade at a discount to gold coin or national banknotes.

Some corporations issued “scrip,” informal currency that amounted to a promise to redeem in gold coin or national banknotes at some point in the future. Streetcar companies in Omaha and St. Louis paid their employees in nickels from the fare boxes or in five‐cent fare tickets.a Bank checks were useful as cash only locally, since in an environment where banks discriminated among payees, being a distant correspondent was a disadvantage. This near‐money traded hands at a discount to gold coins and paper currency, reflecting fears about the solvency of banks, companies, and individuals. No region or major city was spared from the effects of the panic.19 Economist A. Piatt Andrew estimated that by the nadir of the Panic, more than $500 million20 in substitutes for cash had been issued nationally, which was equal to about 28 percent of all the currency in circulation before the crisis.21

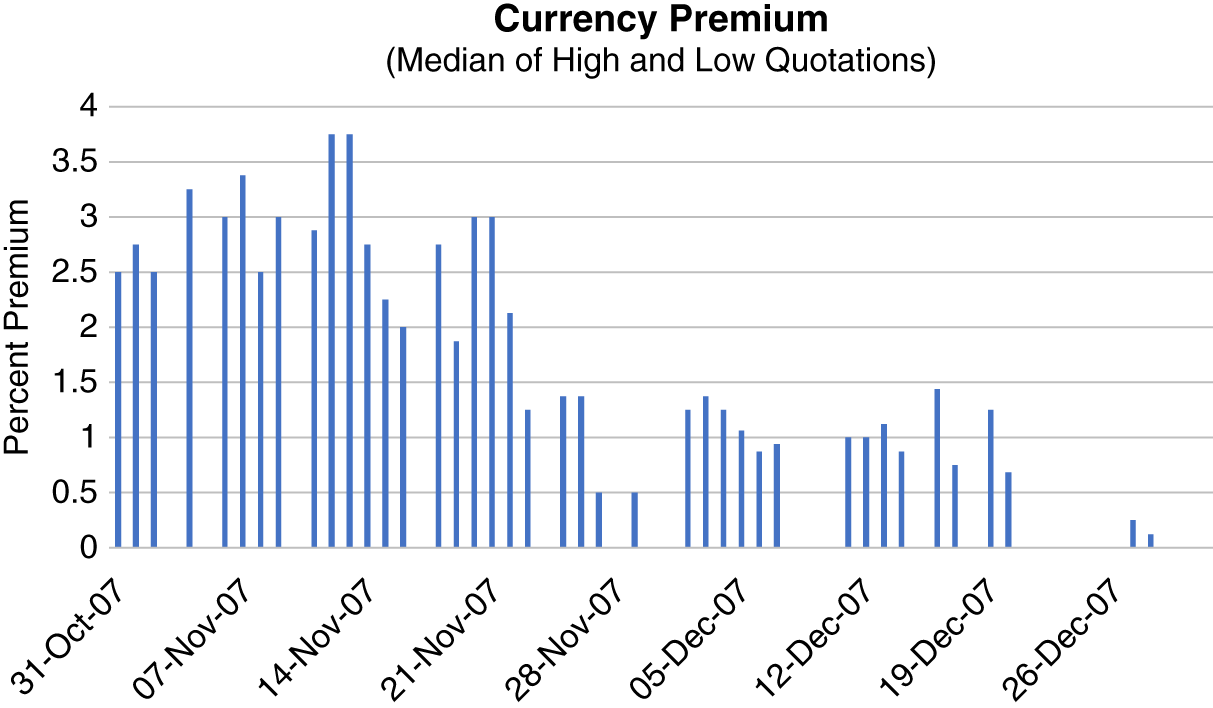

Hoarding (especially of gold coin), the effusion of money‐like forms of payment, and uncertainty about whether the proto‐money would be redeemable in desirable money ensured that the less desirable money medium would trade at a discount to the more valuable medium. Figure 15.6 displays the size of the gold currency premium from the date it emerged (at the start of payment in loan certificates in New York) until its extinction (largely when the loan certificates were redeemed).

The premium on currency was a barometer of anxieties about the Panic. The figure suggests the period of greatest intensity from late October until mid‐November. And it also shows that the effects of the Panic in New York lasted until January, well past the salubrious utterances of business and government leaders.

To promote the atmosphere of calm engendered by the announcement of the certificates, Morgan and his colleagues encouraged Treasury Secretary Cortelyou to return to Washington. They hoped news of his departure would be perceived as an indication of his confidence in the situation in New York. Likewise, Morgan himself left the city on Saturday afternoon to spend the rest of the weekend at Cragston, his country home in Highland Falls on the Hudson River. He slept soundly on the train, not having had more than five hours of sleep on any night that week.

Figure 15.6 Premium on Currency from October 26, 1907, to January 4, 1908

SOURCE: Authors’ figure, based on data in Andrew (1908a), pp. 292–293.

Hope and Optimism

On Sunday morning, October 27, religious leaders urged calm, offering advice for nervous depositors and investors throughout the city. At the NYCH on Cedar Street, clerks worked busily through the day attending to the mass of details in preparation for the issuance of the certificates on Monday. Encouraged by the certificates plan, the Chase National Bank announced the importation of an additional $2 million in gold from Europe. “We have seen the worst of the ‘panic’ phase,” the Standard of London opined, “and it has to be remembered that the crisis, at any rate, so far as it is connected with extraordinary trade activity, constitutes only a striking example of a complaint common in almost every financial centre, namely, a growth in the demands upon capital out of proportion to the supply.”22 Around 4 p.m., Morgan boarded a train back to New York City. Despite the rainy weather, it appeared that the skies were finally clearing.

On Monday morning, October 28, the wave of good news continued. The NYCH had authorized about $101 million in loan certificates on Saturday, of which their actual use would peak at $88 million in December. Gold shipments began to arrive from all over the world, including England, Argentina, Paris, and Australia, and the total was expected to reach $20 million. Though numerous depositors were still lined up at the Trust Company of America and the Lincoln Trust, no new runs were reported. The New York State Superintendent of Banks, Clark Williams, even announced that several banks that had closed during the past week had submitted applications to reopen.

On the Stock Exchange, call money rates reached as high as 75 percent, but the day’s final loan was made at 6 percent, and all brokerages were able to obtain the money they needed. Around 11 a.m., several brokers had approached Perkins asking if more money would be available through the banking pools, but he and the others were opposed to resorting to this measure again. The bankers were convinced that sufficient liquidity was available, and money pools were all but abandoned. “The various pools which were formed last week to render assistance to the call money market have by reason of the action taken by the New York Clearing House Association been dissolved,” A. B. Hepburn, president of Chase National Bank announced. “Brokers should now make their arrangements for loans with their own banks.”23 To show his confidence in the situation, J. P. Morgan remained uptown at his library all day long.

New York City Turns to J.P. Morgan … Again

The apparent calm, however, belied a new crisis that was brewing. “Outwardly, in the newspapers and as far as the public knew, everything was serene,” Perkins said, “but four or five of us were possessed of information that made us fear that all the work we had done in the preceding week might come to naught at any moment.”24 Perkins, Morgan, and the other leading bankers had learned that the City of New York itself was on the verge of financial collapse.

On Sunday evening, an official from the City of New York came to George Perkins privately to explain that unless the municipal government could raise $20 or $30 million by November 1, the city would default on loans. It was already unable to meet its payroll obligations and could not pay its contractors. The city had tried, and failed, to float bonds over the previous summer, and succeeded in doing so in September only with Morgan’s intervention. During the fall, the city had been financing its expenditures with the $40 million in short‐term loans that previously had been underwritten by J. P. Morgan & Company. In September, the city felt confident of its ability to repay these debts quickly, but the intervening financial crisis and resultant market conditions now made that impossible. The city official said they had tried to access the public markets for three or four days, but they had succeeded in raising only a few million dollars. “To raise even one million dollars seemed about as possible at that moment as to move a mountain,” Perkins said.25

Around 4 p.m. on Monday, October 28, Mayor McClellan, his deputy, the city controller, and the chamberlain came to see Morgan personally at the library. They explained that after the previous summer’s financing they discovered that they needed to use the entire $40 million almost immediately, and now they needed additional funding to carry them through the rest of the year. After a few hours spent discussing the city’s finances, they adjourned and agreed to meet again the next day at 3:30 p.m. Neither Morgan nor his associates believed they could place the city’s short‐term obligations on the market in Europe, and there would certainly be little appetite for them in America; given the current rates on money, a 6 percent return was hardly attractive. But the consequences of the city’s financial failure would be severe. “We all realized the gravity of the situation,” Perkins said. “How much fuel would be added to the flame if the credit of the City of New York should be questioned at such a moment?”26

The next day at the appointed time, Morgan and the others renewed their discussion with the mayor and his delegation. Then, without saying a word, Morgan sat at his desk in the library and took up a pen and began to write. “With scarcely a hesitation, without even stopping to select a word,” Perkins recalled, “he covered three long sheets of paper and then after reading it over, he handed it to me and said, ‘See what Messrs. Baker and Stillman think of that.’”27

With speed and clarity, Morgan had crafted a proposal that J. P. Morgan & Company would take $30 million of the city’s revenue bonds, with optional terms of one, two, or three years, bearing an interest rate of 6 percent. There was an option on $20 million more, and the city was required to appoint a commission to examine its finances. Morgan planned to exchange these bonds for clearing house certificates by handing them over to the First National and National City Banks. This measure would thereby result in an additional $30 million in liquidity for the City of New York as well as provide $30 million in credit for the city through the banks.

After a discussion lasting about 20 minutes, the bankers and a lawyer concluded that Morgan’s extemporaneous term sheet “was practically perfect both from the standpoint of an offer and the concise manner in which it had been put.”28 The meeting adjourned just before 7 p.m., and the representatives of the City of New York departed with a contract to receive $30 million from J. P. Morgan & Company, the First National Bank, and National City Bank the very next day. With the flourish of his pen, J. P. Morgan had quelled the financial threat to the City of New York.

The remainder of the week was very encouraging. On Wednesday, October 30, the Trust Company of America accepted over $100,000 in deposits more than it had paid out; it also reported seeing the fewest number of depositors than on any previous day, with fewer than 20 remaining at the close of business. By Thursday, the Trust Company had refunded $1 million that had been loaned to it over the past week.

Severe Pressure Remains

Money rates were still relatively high and stress was apparent on the Exchange, but the average interest rate on call money had declined to 20 percent, and at one point had even reached a low of 8 percent. During the week, the Bank of England raised its discount rate from 4.5 to 5.5 percent, indicating that the Bank was trying to stanch the flow of gold to the United States. By November 4, the Bank of England’s rate would rise to 7 percent, the highest since 1873. Central banks in France and Germany followed suit. Secretary Cortelyou noted “severe pressure” on the money markets in those countries and observed that the grave conditions were not “localized in the United States.”29

These global conditions reflected the fact that gold continued to arrive in the United States at a volume not seen since 1893. Still, very few firms on the Exchange were accepting margin business and the demand for cash remained strong because of numerous end‐of‐month payroll and debt obligations. The one alarming event during the week was the failure of a stock exchange house, Kessler & Company. That failure might have passed unremarkably, but it foreshadowed a new and unexpected turn in the crisis for which J. P. Morgan’s own motivations would ultimately be called into question.

Notes

- a. Steven Horwitz (1990), p. 643, wrote that the streetcar fare tickets “circulated fairly widely for several weeks, evidently because they had a redemption value as streetcar rides… . The essence of money is its general acceptability. Historically, stones, shells, tobacco, cigarettes and cattle have all served as money. Indeed, as Mises put it, something can become money only ‘through the practice of those who take part in commercial transactions.’”

- 1. New York Times, October 28, 1907, p. 1.

- 2. New York Times, October 23, 1907, p. 5.

- 3. Morison, Blum, Chandler, and Rice (1952), Volume 5, p. 823.

- 4. New York Times, October 26, 1907, p. 1.

- 5. New York Times, October 27, 1907, p. 5.

- 6. New York Times, October 26, 1907, p. 1.

- 7. New York Times, October 29, 1907, p. 2.

- 8. New York Times, October 27, 1907, p. 2.

- 9. Response of the Secretary of the Treasury to Senate Resolution No. 33, of December 12, 1907 (U.S. Department of the Treasury, 1908), p. 14.

- 10. Ibid., pp. 23, 31.

- 11. Sprague (1908), p. 367.

- 12. The estimate of $200 million is from Maurice L. Muhleman, Monetary and Banking Systems: A Comprehensive Account of the Systems in the United States (New York: Monetary Publishing, 1908). The higher figure, $296 million, is from Noyes (1909a), p. 188.

- 13. The figure of 8 percent equals $233 million divided by $2,813 million, an estimate of currency in circulation given in Historical Statistics of the United States (1970) Series X420‐423, Volume II, p. 993. The currency in circulation in 1907, $1.784 billion, is from Friedman and Schwartz (1963).

- 14. “Leaders’ View of Situation,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 27, 1907, p. 2.

- 15. Response of the Secretary of the Treasury to Senate Resolution No. 33, of December 12, 1907 (U.S. Department of the Treasury, 1908), p. 225.

- 16. For more information on the incentives and analytics around gold importation to the United States during the Panic of 1907, see Rodgers and Wilson (2011) and Rodgers and Payne (2014).

- 17. Wicker (2000), Chapter 5, “The Trust Company Panic of 1907.”

- 18. Andrew (1908b), p. 507, estimates that $238 million in clearing house certificates were issued. Our total of $219 million derives from the outstanding certificates given in the report of the Comptroller of the Currency for 1907. Outstanding volumes would seem to give a better indication (than issuances) of the economic impact of the use of clearing house loan certificates.

- 19. Cannon (1910) identifies the use of clearing house loan certificates in the following cities: New York, New York; Augusta, Georgia; Baltimore, Maryland; Buffalo, New York; Canton, Ohio; Chicago, Illinois; Cincinnati, Ohio; Denver, Colorado; Des Moines, Iowa; Detroit, Michigan; Fargo, North Dakota; Fort Wayne, Indiana; Grand Rapids, Michigan; Harrisburg Pennsylvania; Kansas City, Missouri; Little Rock, Arkansas; Los Angeles, California; Omaha, Nebraska; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Portland, Oregon; St. Joseph, Missouri; St. Louis, Missouri; St. Paul, Minnesota; Salt Lake City, Utah; San Francisco, California; Savannah, Georgia; Seattle, Washington; Sioux City, Iowa; South Bend, Indiana; Spokane, Washington; Tacoma, Washington; Topeka, Kansas; Wichita, Kansas; and Wheeling, West Virginia. Casual review of newspapers and other publications that year suggests that this list is not exhaustive.

- 20. Andrew (1908b), p. 515.

- 21. The percentage estimate is calculated against all cash in the hands of the public, $1.784 billion, from Friedman and Schwartz (1963), p. 706.

- 22. New York Times, October 28, 1907, p. 1.

- 23. New York Times, October 29, 1907, p. 1.

- 24. Account by Perkins in Crowther (1933), unpublished manuscript.

- 25. Ibid.

- 26. Ibid.

- 27. Ibid.

- 28. Ibid.

- 29. Response of the Secretary of the Treasury to Senate Resolution No. 33 of December 12, 1907, Calling for Certain Information in Regard to Treasury Operations, United States Depositaries, the Condition of National Banks, etc. (U.S. Department of the Treasury, 1908), pp. 15, 16.