Chapter 19

Ripple Effects

Worried over the belief that he had lost $20,000, his balance in the Knickerbocker Trust Company of New York, Valentine Hayerdahl of Mount Vernon committed suicide yesterday afternoon by shooting himself through the head at his home, 53 Rich Avenue, Chester Hill. Mr. Hayerdahl, who was formerly a salesman for the Haviland China Company of New York, resigned a short time ago to go into business for himself. All the money Mr. Hayerdahl owned was on deposit in the trust company. He told several friends that he believed that his life’s earnings were gone.

—New York Times, November 27, 1907

The Panic of 1907 reverberated in markets, governments, and the lives of individuals throughout the United States and around the world. Some measures suggested that the instability in New York had receded by January 1908. But it lingered in the financial system of the rest of the country for several more months. And the Panic proved not to be just a financial crisis—it spilled over into the real economy, society, politics, and public policy, in which the crisis proved to have a much longer influence.

Initial Views of the Panic Beyond New York City

Initially, the impact of the panic elsewhere in the United States appeared to be mild. Just as the New York trust companies were experiencing the first shock waves of instability in late October 1907, dispatches from other cities and regional money centers showed little indication that anyone expected the contagion to spread beyond Wall Street. In fact, contemporaneous reports from Chicago and cities further west even implied that the malaise was a consequence of New York‐based speculation and imprudent banking practices, hinting that it would have little effect elsewhere. “We are getting more independent of Wall Street every day, and business conditions here are not disturbed by the flurries of the market there,” declared a St. Louis businessman. “St. Louis people are lending money in New York instead of borrowing it.”1 Similarly, the president of the Union Trust Company of Chicago boasted, “There has not been the slightest indication of alarm over the situation anywhere in Chicago today. It simply shows what has long been an established fact—that Chicago banks are not affected by the ups and downs of the stock market. Chicago credit is as solid as ever—there is no Wall Street in Chicago.”2

On October 23, prominent bankers in Chicago asserted the probity of their operations and discounted the likelihood of financial unrest there. George M. Reynolds, president of the Continental National Bank and a member of the Chicago clearing house committee, said, “If you drop a pebble into a pond the ripples will extend to the farthest banks of the body of water. If you watch the ripples closely, however, you will notice that they become invisible a short distance from the spot in which the pebble fell. It is just so with the present financial situation. The pebble that has caused the New York trouble has made ripples fly, but they disappeared before they reached Chicago.” Similarly, John J. Mitchell, president of Illinois Trust and Savings Bank, said, “The secret of the situation is that we have no promoting schemes here. Ours is the solid business variety of investments, and there is not occasion for worry about them.”3

Then Troubles Spread to the Interior

Notwithstanding the evident disdain for events unfolding in New York City, within mere days the tremors of the panic were being felt far from Gotham. “The most sinister feature of today’s financial news is the spreading of the strain to other cities” was already being reported by the Manchester Guardian on October 25. “It is no longer possible to affirm that the trouble is localized in New York.”4 By the next day, banks elsewhere in the nation were suspending operations; even the clearing house of St. Louis made a proactive decision to begin the issuance of certificates upon demand. This was quickly followed by similar actions by bank clearing houses across the country.5 Going even further, on October 28 the governor of Oklahoma ordered the immediate closure of every bank in the Oklahoma and Indian Territory as a precautionary measure, following the decision by the banks of Kansas City and St. Louis to forward cash to the banks of the Southwest.6 By the end of the Panic, only six states did not suspend or limit payments.7

The national experience of financial crisis reminded business leaders of the linkages and interdependencies across regions. President Theodore N. Vail of the American Telephone & Telegraph Co., following a trip to inspect affiliate companies in the West, admonished those who held narrower views:

The present crisis, whether we call it a money stringency, a business depression, or an old‐fashioned panic, is teaching the West a lesson which years of unbroken prosperity had caused it nearly to forget, and that is, the essential unity of the country. In a very large sense, the states are all “members of one another.” It is impossible for Wall Street to be suffering in the throes of financial stringency without the banks and industries of Missouri, Kansas and Oklahoma feeling the effect. The West seems to have forgotten this fact. It has been the fashion there to decry the “gamblers” of Wall Street and to speak of the eastern money centers as if they were isolated communities. The West is now feeling, and in the coming months is likely to feel, a severe financial stringency, with all the usual accompaniments of a money disturbance.8

December 1907–January 1908: Signs of Improvement

The intensity of the Panic in late October and the precipitous decline in order volume and productivity across key industrial sectors during the months that followed was matched only by the apparent abruptness with which conditions began to improve. Barely two months after the crisis had started, notes of confidence began to appear in the popular press, with nearly buoyant optimism by the year’s end. The Washington Post reported that:

[I]t is perfectly plain that the era of good times has begun and that the panic of 1907, with its resulting depression, will be confined almost entirely to 1907… . Business men are reassured. The world is not coming to an end. There is no lack of money in Washington. The people have currency with which to transact their business. The banks have gone on exactly as if there had been no flurry. The payments from the Treasury have been heavier than ever, and as dividends are being paid the quantity of money in circulation is larger than usual. The big holiday business being done by the shops and business houses is excellent proof of good times.9

As evidence of an incipient recovery, executives from United States Steel reported that planned railroad improvements were expected to recommence, resulting in a “resumption of activity [in 1908] that would speedily erase all evidence of the recent shock.”10

While some of the bullishness about the hoped‐for turnaround may have simply been wishful thinking, there was nonetheless a deep conviction that the underlying strength of the U.S. economy, which had been booming in recent years, would buttress its resilience in the wake of the crisis. One contemporary journalist observed that, while the United States had only 5 percent of the world’s population, the nation had come to produce 20 percent of the world’s wheat, 25 percent of its gold, 33 percent of its coal, 35 percent of its manufactures, 38 percent of its silver, 40 percent of its iron, 42 percent of its steel, 52 percent of its petroleum, 55 percent of its copper, 75 percent of its cotton, and 80 percent of its corn.11 It seemed unthinkable at that time that economic dislocations would be anything but short‐lived. The Washington Post said:

The “panic” is having a hard time trying to live to the end of the year. Prosperity is rapidly reducing the panic to a skeleton of its former self. Many cities have resumed currency payments, the [bank] holidays have been called off in the West, and the premium on currency in New York has dropped to a trifle, with indications that it will disappear within a week. Confidence has returned to every corner of the country. The Christmas buying was heavy, everything considered, and in some places, it excelled that of last year. Mills and factories are preparing for an active business in the new year.12

And so it was; even the worst‐hit firms began to show signs of life well before 1908. Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company, for instance, reported a late‐December order for $2 million, which resulted in an accelerated reopening of one of its major plants in Pittsburgh. At the same time, both the American Shipbuilding Company and the American Steel and Wire Company announced the rehiring of several thousand workers by January 1908. And the Sherwin‐Williams Paint Company, which had sidelined all 250 salespeople in October, reported that they would be on the road again by the first week of the new year.

By early January 1908, banks in New York lifted their suspension of payments in specie.13 And the New York Clearing House (NYCH) ended the issuance of clearing house loan certificates and resumed interbank payments in gold. The premium on currency had completely disappeared by January 17.14 On the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), call loan interest rates had returned to low single‐digit levels by the end of December. Stock prices began to rise in February, commencing a slow “V‐shaped” recovery, as Figure 19.1 depicts.

The Real Economy: Deep Immediate Impact

Beyond the banking sector, the panic hit the real economy with unanticipated intensity. Even though 1907 was, for instance, a record‐breaking year for iron and steel production, the final quarter staggered the industry with a “partial but apparently progressive paralysis.”15 By year‐end, more than a third of total productive capacity in the industry had been idled. The cause for this severe contraction was a major cancellation of orders by the railroads, many of which had become anxious about their own ability to secure the financing they needed to make their purchases. Consequently, the pronounced loss of confidence by the railroads in the banking and financial system hit the iron and steel producers with uncommon speed and ferocity, causing them to shutter operations within just a few weeks. Thus began a cascading cycle of retrenchment, triggered not by the natural ebb and flow of supply and demand, but largely by the seizing‐up of capital and credit when and where it was needed most.

Figure 19.1 Recovery in Share Prices Began in 1908

SOURCE: Authors’ figure, based on data from National Bureau of Economic Research, Average Prices of 40 Common Stocks for United States [M11006USM315NNBR], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/M11006USM315NNBR, April 30, 2022.

Commodity prices fell 21 percent, eliminating virtually the entire increase from 1904 to 1907.16 Industrial production dropped more than in any other U.S. panic up to 1907.17 The dollar volume of bankruptcies declared in November spiked up by 47 percent over a year earlier—the Panic would be associated with the second‐worst volume of bankruptcies up to 1907.18 Gross earnings by railroads fell by 6 percent in December,19 production fell 11 percent from May 1907 to June 1908, wholesale prices fell 5 percent, and imports shrank 26 percent.20 Unemployment rose from 2.8 percent to 8 percent,21 a dramatic increase in a short period of time. Immigration, which had reached 1.2 million people in 1907, dropped to around 750,000 by 1909; it would not reach 1 million again until 1910.

The Commercial and Financial Chronicle wrote, “It is probably no exaggeration to say that the industrial paralysis and the prostration was the very worst ever experienced in the country’s history.”22 In characteristic understatement, Jack Morgan wrote to his partners in London, “I do not think that 1907 was a good year anywhere, from what I can make out.”23

Hysteresis

Economic data reveal that the Panic of 1907 was associated with a subsequent malaise, a lower rate of economic performance. Economists call this “hysteresis,” which means the persistence of slower growth well after the event that precipitated the slowdown. Figure 19.2 shows the actual path of real GDP per capita. And superimposed on the actual path are two hypothetical trends. One trend assumes that GDP per capita after 1906 grew at the average annual rate it achieved from 1896 to 1906 (3.9 percent); the other trend assumes the average annual growth rate from the end of the Civil War (1865) to 1896 (1.9 percent). In neither case does the actual GDP per capita return to the long‐run trend by 1929, the onset of the Great Depression—it remains an arresting downshift, despite the fiscal stimulus of federal government spending during World War I and the consumption boom of the “Roaring ’20s.” The economic effects of the Panic of 1907 and its recession proved to be a major setback for the nation.

Figure 19.2 Growth in Gross Domestic Product per Capita Compared to Historical Trend Projections

SOURCE: Authors’ figure, based on data in Maddison Project Database, version 2020. Jutta Bolt and Jan Luiten van Zanden, “Maddison style estimates of the evolution of the world economy. A new 2020 update” (2020),https://www.rug.nl/ggdc/historicaldevelopment/maddison/releases/maddison-project-database-2020?lang=en.

One possible cause of the setback was economic “scarring.” Modern researchers have found that economic downturns can lead to long‐lasting damage to workers’ productivity, education, and mobility.24

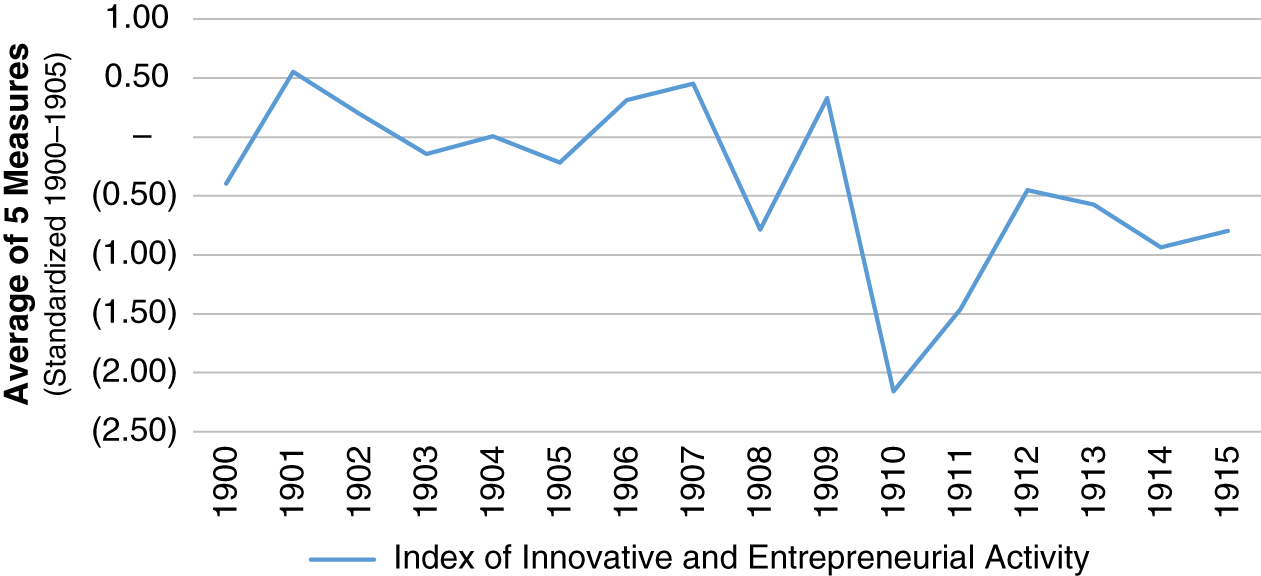

A related cause could be the chilling effect of the crisis on innovation and entrepreneurship. We examined the time trends of three measures: (1) total factor productivity, (2) patents granted, and (3) the change in the number of concerns in business. From these measures we created an index about entrepreneurship and innovation, depicted in Figure 19.3. The figure shows a level trend from 1901 to 1907, after which the trend declines in 1908, recovers, declines again in 1910, and comes to rest at a somewhat lower level thereafter.

Figure 19.3 Trend of Innovative and Entrepreneurial Activity

NOTE: This figure plots an average of three measures: (1) total factor productivity, (2) patents granted, and (3) the change in the number of concerns in business. Measures 2 and 3 were converted to a per‐capita quantity. All three measures were converted to standard quantities (relative to performance over the years 1900–1905) and then averaged to produce the time series in the figure.

SOURCE: Authors’ figure, based on data from Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1970 (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1975), pp. 948, 957, 958, and 959. U.S. population from Maddison Project Database, version 2020. Jutta Bolt and Jan Luiten van Zanden, “Maddison style estimates of the evolution of the world economy. A new 2020 update” (2020), https://www.rug.nl/ggdc/historicaldevelopment/maddison/releases/maddison-project-database-2020.

This evidence of hysteresis in Figures 19.2 and 19.3 suggests the pivotal economic impact of the Panic of 1907. This impact was not merely local, but national and global. Nor was it merely temporary; it spanned many years.

Examples of Two Industrial Firms

Why a financial crisis can scar economic performance is illustrated by a comparison of two well‐known, quasi‐monopolistic enterprises of the time: the General Electric Company and the Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Company. At the height of the crisis in late October, Westinghouse was swiftly placed into the hands of receivers, following its failure to secure the renewal of $4 million in short‐term notes from its lenders. This sudden cash stringency resulted in the company’s inability to pay 11,000 members of its Pittsburgh workforce, which was then immediately followed by a massive decline in its stock price by nearly 56 percent. The spillover from the Westinghouse receivership was the closure of the Pittsburgh Stock Exchange the very same day, staying dark for nearly a week.

On the other hand, as described in an analysis by contemporary scholar Niles Carpenter Jr., General Electric fared far better during and after the most critical period of the panic in late fall 1907.25 Despite “fundamental similarities underlying the financial operations” of the two companies, including close ties with powerful members of the nation’s financial elite, such as J. P. Morgan himself, GE emerged nearly unscathed from the surrounding financial catastrophe.

According to Carpenter, GE’s resilience was largely a function of its more prudent financial policies. Whereas Westinghouse relied heavily on commercial paper and short‐term notes to fund operations, GE maintained “a larger margin of safety” by consistently keeping a greater proportion of working capital in reserve. GE supported this strategy by offering a lower dividend rate (than Westinghouse), implementing heavier depreciation charges, and maintaining a preference for stock issuance versus bonds to support business expansion. In fact, during the crisis itself, GE remained “effectively inactive” in the capital markets. When it did look for new financing, it only did so through convertible bonds in the later stage of the Panic as an emergency measure of relief. Though Westinghouse survived the Panic, it remained in the hands of receivers until April 1908, whereas the crisis had “no appreciable effect” on the General Electric Company.

While GE’s “cautious conservativism” had served the company far better than Westinghouse’s debt‐fueled fiscal policies, both companies had entered 1907 on roughly equal terms, following a period of unprecedented growth in the electrical equipment industry. In fact, by the early part of 1907, both firms had seen the largest volume of business in their respective histories. And even after the trouble commenced in March 1907, the overall economic momentum continued to sustain the electrical business. So, when the Panic erupted in October, the negative effects were not a function of any fundamental business instability or weakness in the economy. To the contrary, business growth was strong, tempered only by the sudden decline in stock prices and an inability (at least for Westinghouse) to secure financing to meet immediate needs.

Such dynamics as experienced by Westinghouse and General Electric were playing out elsewhere in the U.S. economy. As Carpenter notes, “For a large part of this time, the two corporations under consideration did not vary much from any of the dozens of other large industrials attempting to ride out the storm.” Even during the late, critical days of October, executives at the nation’s largest industrial companies remained confident about their firms’ prospects and were generally optimistic about economic conditions, while acknowledging that a contraction was likely. “Representatives of the leading industrial companies declare that the recent financial disturbances have not affected general business to the extent one would suppose,” the Wall Street Journal reported on October 29, “and now that the worst is over, there should be a rapid restoration in confidence.”26 As evidence, the newspaper cited the soundness of the United States Steel Corporation and the Standard Oil Company, both of which held substantial reserves of cash on hand during the crisis and could be expected to weather a period of monetary stringency.

International Impact

Responding to the gold imports by the United States, central banks in Britain, France, and Germany raised their base interest rates to attract gold back to their countries. The Bank of England raised Bank Rate to 7 percent, the highest since 1865.27

More broadly, 1907 was a year of global financial instability. The U.S. crisis coincided with financial crises in Egypt (January to May 1907), Japan (July and beyond), Hamburg (October), Chile (October), Amsterdam (September–November), Genoa (September), and Copenhagen (winter 1908).28 One conduit for contagion was international ownership of American securities—when prices on the NYSE plummeted, global institutional investors took losses. In Hamburg the firm of Haller Sohler & Co. failed because of its sizeable holdings in United Copper and Amalgamated Copper, while some 15 firms in Amsterdam failed in November owing to the decline in U.S. equities.29 Contemporary Wall Street observer Alexander Dana Noyes wrote,

The case simply was that the crisis affected the world at large, part of the world passing through the acute stage before our own markets did… . The strain on the financial world was so severe a character that it was bound to result in a break in the chain of credit, wherever the link was weakest or wherever the strain was greatest. The link was weakest, no doubt, in markets such as Egypt and Chile; the strain was incalculably greatest in New York, where credit had been so grossly abused, and where inflation of prices had prevailed on such as scale of magnitude as to render the situation, despite the country’s immense resources, more vulnerable than that of any other in the long chain of connecting markets.30

A case in point was the impact of the crash and Panic of 1907 on Mexico, a country heavily dependent on mineral and agricultural prices, and on flows of investment capital from the United States. Historian Kevin Cahill noted:

In 1906 over $57 million of foreign investment poured directly into Mexican banks, but when this influx ceased at the end of 1907, money became scarce… . The loss of foreign investment caused the total assets of Mexican banks to plummet from $360 million in 1907 to $305 million in 1908… . New bank loans also declined… . A large majority of borrowers were unable to repay their loans. Two consecutive years of drought curtailed agricultural production, making it impossible for the commercial farmers to repay their debts. Moreover, individuals throughout the republic had borrowed money to buy stocks on margin. The collapse of the economy caused stock prices to decline, and many of these investors faced bankruptcy. The inability of the banks to collect their debts produced profound difficulties for banks at all levels.31

Cahill suggested that the financial strains in Mexico had political consequences and that the panic and subsequent depression were among the catalysts for the Mexican Revolution. “[Scholars] contend that because Mexico depended heavily on foreign markets and capital, particularly that of the United States,” Cahill wrote, “the U.S. depression crippled the Mexican Economy. Generating widespread dissatisfaction with President Porfirio Díaz’s government, it thus was one of the factors that provoked the Maderistas and other revolutionaries to rebellion in 1910.”32

The experience of Mexico from 1907 illustrates the fragility of developing economies in the face of financial crises. Dependent on foreign direct investment, borrowing in foreign currencies (called “original sin”33), reliant on commodity exports whose prices oscillate wildly in a crisis, and governed by a regime for whom a poor populace has waning patience comprised an explosive mixture.

Social Impact of the Crisis

The Panic of 1907 lingered in other ways, less easily captured in financial and economic data. Comments in letters, telegrams, and the news media suggested immense social stress. To gauge the association of the Panic with subsequent social stress, we constructed an index based on five factors: (1) number of homicides, (2) number of suicides, (3) numbers of African Americans lynched, (4) failure rate of businesses, and (5) deaths from cardiac disease, depicted in Figure 19.4.

The index of social stress rose materially in 1907 and peaked sharply in 1908, following the Panic year—in statistical terms, the jump cannot be attributed to random variation or “noise.” By the third year after the Panic, it still had not subsided to pre‐panic levels.

Political Impact

Financial crises tend to be hard on elected officials. No federal government election occurred in 1907. But 1908 was a significant year: President Roosevelt (who had declared that he would not run in 1908) engineered the Republican Party nomination of William Howard Taft for president. Taft was elected by a 52 percent popular majority. And the Party continued to hold majorities in the two houses of Congress. However, the election results began a weakening trend, as depicted in Figure 19.5.

Figure 19.4 Trend in Index of Social Stress

NOTE: This figure plots an average of five measures: (1) number of homicides, (2) number of suicides, (3) numbers of African Americans lynched, (4) failure rate of businesses, and (5) deaths from cardiac disease. All five measures were converted to standard quantities relative to performance over the years 1900–1906, and then averaged to produce the time series in the figure.

SOURCE: Authors’ figure(s), based on data from Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1970 (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1975), pp. 414, 422, 908, and 912.

At the next federal mid‐term election in 1910, the Republican Party lost control of the House of Representatives. And in the disastrous election of 1912, the Republicans also lost the Senate and the White House. Thus, in the five years following the Panic of 1907, a massive realignment took place. Beginning in 1913, progressives stood at the levers of power.

The economic, social, and political ripple effects of the Panic of 1907 went deep into the nation, spread globally, and lasted well after the events of October–November 1907. This contrasted with conventional notions that the Panic was essentially a New York City phenomenon and restricted to a few financial institutions—indeed, the crisis may have started there, but then it radiated widely.

Figure 19.5 Republican Party Election Results, 1894–1914

SOURCE: Authors’ figure, based on data from the following sources: American Presidency Project (Santa Barbara: University of California–Santa Barbara), downloaded May 12, 2022 from https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/statistics/elections. Also, “Party Divisions of the House of Representatives, 1789 to Present,” History, Art & Archives (United States House of Representatives), downloaded May 12, 2022 from https://history.house.gov/Institution/Party-Divisions/Party-Divisions/. And finally, “Party Division of the United States Senate” (Washington, DC: United States Senate), downloaded May 12, 2022 from https://www.senate.gov/history/partydiv.htm.

Notes

- 1. “Banks in Good Shape: Perfect Stability Is Reported from Country at Large, New York Flurry Not Felt,” Washington Post, October 23, 1907, p. 2.

- 2. “Western Banks on a Sound Basis: Chicago Loans Are on Tangible Assets, Not Stock Exchange Value. Flurry Not Felt Here,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 24, 1907, p. 2.

- 3. Ibid.

- 4. “A Sinister Feature: Strain Felt in Other Cities,” Manchester Guardian, October 25, 1907, p. 9.

- 5. “Roosevelt Glad Panic Is Checked, President Congratulates Cortelyou and Financiers Who Aided Him in Crisis, Vote for Certificates, Clearing House Decides on Issue, Despite Opposition of Morgan Interests, Till the Crisis Passes, Other Cities Follow Suit,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 27, 1907, p. 1.

- 6. “Governor Keeps Banks Shut: Oklahoma Concerns Ordered to Take Precautionary Step,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 29, 1907, p. 2.

- 7. Cahill (1998).

- 8. “The West and the Money Crisis: Lessons of Essential Unity of the Country Is Being Taught,” Wall Street Journal, November 13, 1907, 8.

- 9. “Times Decidedly Better,” Washington Post, December 21, 1907, p. 6.

- 10. Ibid.

- 11. “Why the Panic Was Brief: The United States Too Prosperous to Be Frightened at This Time,” Washington Post (from Leslie’s Weekly), December 26, 1907, p. 6.

- 12. “Prosperity Wins Out,” Washington Post, December 29, 1907, p. E4.

- 13. Calomiris and Gorton (1991), p. 161, date the end of suspension at January 4, 1908. Friedman and Schwartz (1963), p. 163, discuss that the U.S. Treasury resumed demanding payments in cash in December, but that some banks continued to restrict payments through January.

- 14. Francis B. Forbes, “Notes on the Financial Panic of 1907,” Publications of the American Statistical Association 11, no. 18 (March 1908): 80–83.

- 15. James C. Bayles, “Unparalleled Year in Iron and Steel,” New York Times, January 5, 1908, p. AFR30.

- 16. Noyes (1909a), p. 207.

- 17. Calomiris and Gorton (1991), p. 156.

- 18. Ibid. See also Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1970 (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1975), Part 2, Chapter V, series V 20–30, which shows a 34 percent spike in the number of business failures in 1908 over 1907, and a 12 percent increase in current liabilities in bankruptcies. This contests Sprague’s assertion that “mercantile failures were not extraordinarily large in number or in amount of liabilities” (1910, p. 275).

- 19. Sprague (1908), pp. 368–371.

- 20. Noyes (1909a), p. 208.

- 21. Cahill (1998), p. 296.

- 22. Ibid.

- 23. J. P. Morgan Jr. Papers, ARC 1216, Box 5, letterpress book #4, January 16, 1908, to January 28, 1909, Morgan Library and Museum. Letter dated January 16, 1908.

- 24. Heckfeldt (2022).

- 25. Niles Carpenter Jr., “The Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company, the General Electric Company, and the Panic of 1907: I,” Journal of Political Economy 24, no. 3 (March 1916): 230–253 and “The Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company, the General Electric Company, and the Panic of 1907: II,” Journal of Political Economy 24, no. 4 (April 1916): 382–399.

- 26. “Recent Financial Disturbances Viewed by Industrial Heads,” Wall Street Journal, October 30, 1907, p. 5.

- 27. Bank of England, “A Millennium of Macroeconomic Data,” downloaded August 30, 2022 from https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/statistics/research-datasets.

- 28. Both Alexander Noyes (1909a), pp. 202–206, and Charles Kindleberger (1977) mention that the Panic of 1907 occurred in a context of financial instability in foreign cities. The notion of contagion, or spread, of financial crises has been documented in the financial crises of the late twentieth century, but the global contagion in 1907 is not as fully documented. Flows of gold into and out of the United States in 1907 are well discussed in contemporary and recent writings on the Panic. It remains to be shown how these flows (or other mechanisms) actually transmitted the financial crisis globally in 1907.

- 29. Rodgers and Payne (2017), pp. 17–18.

- 30. Noyes (1909a), p. 206.

- 31. Cahill (1998), p. 795.

- 32. Ibid.

- 33. B. Eichengreen and R. Hausmann, “Exchange Rates and Financial Fragility,” NBER Working Paper 7418 (Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, 1999).