An Overview of School Safety and Security

Brad Spicer Chief executive officer, SafePlans, LLC

Abstract

This chapter provides core recommendations for threat assessment, preparedness, response, and recovery. The chapter follows the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) cycle of prevention and mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery and explains how those components are applicable to school safety. This chapter also offers the reader ten findings for a Safe Schools Initiative and highlights eleven recommendations for secure school entrances.

Introduction

Protecting schools from violent intruders is complicated and tragically imperfect. There is no one solution and the goal is to identify and streamline the many strategies that can help leaders better protect those around them from acts of violence. Content of this summary is based on best practices and SafePlans’ research and experience, which includes planning and training with local, state, and federal agencies, and work with hundreds of school systems across the nation.

As with most emergencies, violent intruders and active shooters are low-volume but high-impact events. Effective intruder response plans are every bit as necessary in a school’s all-hazards plan as are fire and severe weather. In the past, schools have relied on lockdown plans to meet this need, but a lockdown alone does not effectively address the complex nature of these attacks.

Because no plan or system can totally protect schools from a violent intruder, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) provides a three-option approach. The options are Run, Hide, and as a last resort, Fight.

A lockdown is simply compartmentalization and denying access. Lockdown is a valid security concept, but a lockdown cannot help those having direct contact with an attacker in areas that cannot be secured. Further, most schools treat lockdowns as a very passive response—possibly not the best mindset when confronted by a mass killer.

Building-wide response plans work for fire or severe weather because these threats are less dynamic and fluid than a human-based threat. Compartmentalization (lockdown) certainly helps, because an intruder cannot pose a direct threat to an entire school at once. If the threat is in the cafeteria, compartmentalizing students in classrooms may well be the best response. While a building leader may order a building-wide lockdown, every leader in the school needs to understand their specific response may vary depending on their level of contact and location.

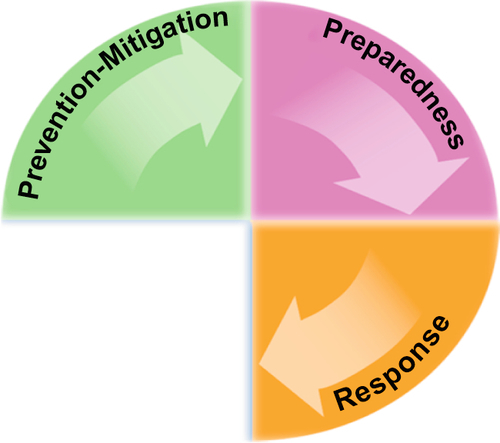

Run-Hide-Fight are response options. It should be noted that “response” is just one element of emergency management. Since its evolution from the civil defense days of World War II, emergency management has focused primarily on preparedness. However, like response, preparedness is also only one phase of emergency management. Current thinking defines four phases of emergency management: Prevention-Mitigation, Preparedness, Response, and Recovery (Figure 5.1). The idea is for each phase to make people and places even safer.

Defining the Threat

For the purposes of this chapter, attacks may be placed into the category of Insider or Outsider.

• Insider. Persons closely affiliated with the target, such as students or former students, carry out Insider attacks. Because of their knowledge of and affiliation with the site, physical security measures can have limited value in preventing Insider attacks. However, this same level of intimacy enables threat assessment programs to be highly effective in preventing Insider attacks.

• Outsider. Persons not closely affiliated with the target carry out Outsider attacks. In these instances the site is often viewed as a soft target that is lacking in sufficient physical security measures to dissuade an attack. Because the attacker is not closely affiliated with the site, it is highly unlikely information has been presented to warrant a threat assessment.

Unfortunately, no amount of physical security can stop every Outsider attack and even the most robust threat assessment programs can fail to identify potentially violent behavior in time to stop all Insider attacks. Therefore, it is vital that all facilities implement intruder response plans and training to mitigate the impact of a violent intruder and maximize survivability for occupants.

Core Recommendations for Prevention and Mitigation

Threat Assessment Programs

Threat assessment is the process of determining the likelihood that any given event will escalate to violence. Threat assessment should be looked upon as one component in an overall strategy to reduce targeted school violence.

All schools should develop a threat assessment team to assess potentially violent behavior. To ensure this behavior is reported, each school should develop a reporting process and provide awareness training to all staff.

Physical Security

Physical security is a vital component of preventing and mitigating acts or violence and should include multiple layers. While there are many components, considerations for schools include: security assessments, law enforcement, private security, access control (building and classroom), and video surveillance.

Core Recommendations for Preparedness

Minimum Safety Standards

Schools should institute formal policies that establish minimum safety standards. This policy should eliminate any ability for staff to allow deviation from accepted best practices, such as securing non-primary entrances or reporting concerning behavior. This policy will also help to shield leaders from pushback regarding inconveniences as a result of these enhanced security measures.

Community Collaboration

Schools should coordinate with the local emergency management and public safety agencies to coordinate the implementation of emergency plans and establish response protocols.

Standardize Emergency Plans

Schools should work with partner agencies to develop and maintain site/building emergency plans that embrace the National Incident Management System (NIMS) guidelines. Minimum requirements include coordination of planning efforts, use of the Incident Command System, planning for special needs populations, and expansion beyond the outdated “lockdown” response to violent intruders.

Emergency Training and Drills

Sites should conduct additional emergency drills that include a minimum of two intruder response drills annually.

Core Recommendations for Response

Best Practice Incident Response Plans

All sites should develop intruder response plans that expand upon basic lockdown principles and include instruction for evacuation and may include fighting back as a last resort.

Tactical Site Mapping Data

First responders should be provided access to tactical site mapping data (i.e., floor plans, images, utility shutoffs, etc.) to improve response times.

Video Surveillance

Measures should be taken to provide law enforcement remote access to on-site video surveillance to enhance tactical response capabilities.

Core Recommendations for Recovery

Family Reunification

One of the first steps to recovery is safely and efficiently reuniting students with their families. Districts should have detailed plans to accomplish family reunification.

Mental Health Plans

Plans should identify mental health resources and detail how they can be applied to incidents of violence involving students.

Continuity of Operations

Plans should identify continuity of operations needs and detail how they can be applied should a violent attack occur.

Prevention and Mitigation

The Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) definitions of prevention and mitigation (Figure 5.2) are as follows:

Prevention: Actions to avoid an incident or to intervene to stop an incident from occurring.

Mitigation: Activities to reduce the loss of life and property from natural and/or human-caused disasters by avoiding or lessening the impact of a disaster and providing value to the public by creating safer communities.1

When someone hears the words “Columbine” or “Sandy Hook” they are likely to remember school shootings. While both were the scenes of horrible attacks, most similarities stop there. The shooting at Columbine high school was an Insider attack that was carried out by students who were part of the Columbine school community. The shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School was carried out by someone whose only affiliation with the elementary school appears to have been geographic.

Anything short of federal courthouse-level physical security is unlikely to have stopped the Columbine killings, but there were numerous warning signs. There is no reason to think that the staff at Sandy Hook Elementary could have observed any warning signs from Adam Lanza (the shooter), but more robust physical security could have deterred his attack or, at a minimum, sufficiently delayed his entry to allow the implementation of a more successful intruder response plan.

Threat Assessment

The goal of a threat assessment is to determine if someone poses a threat, not simply to verify if they have made a threat. This is, perhaps, the most proactive thing a school can do to improve safety. A threat assessment is a proactive approach to assessing, evaluating, and intervening in a potentially violent situation by assigning a degree of dangerousness.

At SafePlans, we have helped hundreds of districts develop formal threat assessment teams using resources such as Gavin de Becker & Associates MOSAIC tool (https://www.mosaicmethod.com) and the Secret Service Safe School Initiative (http://www.secretservice.gov/ntac_ssi.shtml). Both offer a great deal to help schools predict violent behavior and prevent attacks.

In his book The Gift of Fear, Gavin de Becker outlines a simple and powerful way to efficiently assess the seriousness and dangerousness of a high stakes prediction. The approach is called JACA and every school leader should consider this approach when trying to determine if a person is truly dangerous.

JACA is an acronym for Justification, Alternatives, Consequences, and Ability. These are elements that exist when there is a serious risk of violent behavior. Apply JACA from the viewpoint of the person you are assessing, not your own, and answer the following questions:

• Justification. Does the person feel justified in taking violent action?

• Alternatives. Does the person feel there are alternatives to violence?

• Consequences. Is the person concerned about the consequences of a violent action?

• Ability. Does the person have the ability to carry out an attack?

Indication of dangerousness

0 JACA elements present: No threat

1 JACA elements present: Mild threat (Monitor)

2 JACA elements present: Moderate threat (Refer for Full Assessment)

3 JACA elements present: Severe threat (Refer for Full Assessment)

4 JACA elements present: Profound threat (Refer for Full Assessment)

JACA is simply a snapshot, and in no way replaces the need for school districts to develop a formal and comprehensive threat assessment program that includes student and faculty awareness training, a formal reporting process, a trained multidisciplinary threat assessment team and a case management program.

The Secret service’s safe school initiative

After the Columbine shooting, the United States’ Secret Service and the Department of Education implemented the Safe School Initiative (SSI) and offered suggestions for schools and parents. According to the Final Report and Findings of the Safe School Initiative, “to the extent that information about an attacker’s intent and planning is knowable and may be uncovered before an incident, some attacks may be preventable.”2 While the finding may seem innocuous, the fact that acts of targeted violence are not impulsive means there are opportunities to observe behavior and intervene before the attacks are carried out.

10 Core findings of the safe school initiative3

1. Targeted school shootings are not impulsive acts.

2. Prior to most incidents, the attacker told someone about his idea and/or plan.

3. Most attackers did not communicate direct threats to their targets prior to the attack.

4. There is no accurate or useful profile.

5. Prior to the attack, most shooters were observed engaging in some behavior that caused others concern, or indicated a need for help.

6. Most shooters had difficulty coping with significant personal loss or personal failures.

7. Many attackers felt persecuted or injured by others prior to the attack.

8. Most attackers had access to, and had used, firearms prior to the attack.

9. In many cases, other students were involved in, or had prior knowledge of the attack.

10. Despite prompt responses, most attacks were stopped by means other than law enforcement intervention and were brief in duration.

Conclusion of the safe school initiative

Targeted violence is the end result of an understandable, and oftentimes discernable, process of thinking and behavior.4

The fact that most attackers engaged in preincident planning behavior and shared their intentions and plans with others suggests that those conducting threat assessment inquiries or investigations could uncover this type of information.

In order for threat assessment to be effective, concerning behavior must be reported. At SafePlans, we encourage districts to incorporate a See Something-Say Something program to encourage reporting of any behavior that causes concern for your safety or the safety of the others. For example, in the case of immediate danger or threat, faculty should call 911. For nonemergency concerns, faculty, or staff should contact the building principal or other specific person or a dedicated tip line.

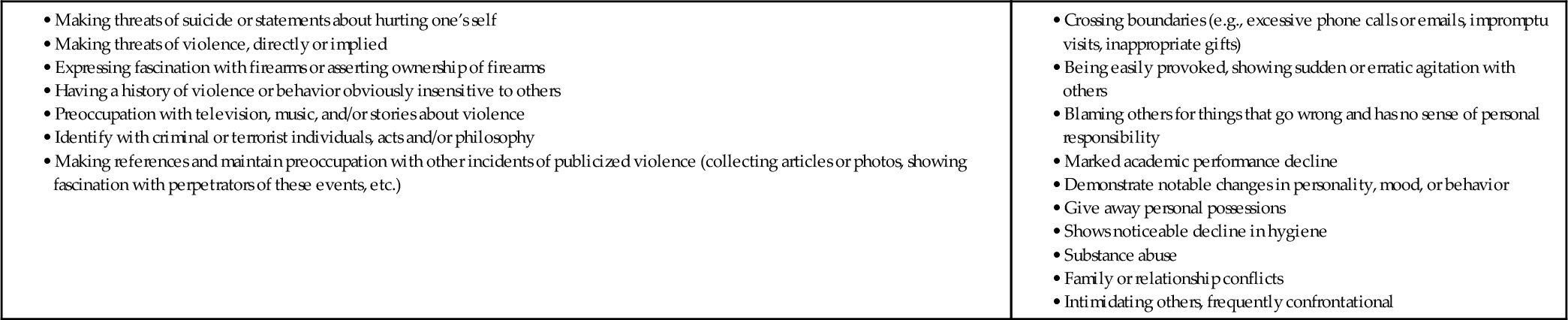

What is meant by concerning behaviors

Although the terms, “concerning,” “worrisome,” and "threatening” are subjective in nature, the list of examples in Table 5.1 provides some context when assessing whether a student may need additional support.

Table 5.1

Behavioral Symptoms That May Cause Concern

Preventing Violence

There is no 100% proven method of predicting when someone may become violent. Listed in Table 5.2 are some indicators or signs that may warrant closer attention and possibly intervention. It is important to consider the context of the warning signs, such as tone of voice and your level of familiarity with the person making the troubling statements.

Table 5.2

Signs That May Warrant Intervention

Physical Security in Schools

For the purpose of this chapter, physical security describes measures implemented with the goal of protecting people and property inside a school. A primary goal of physical security is managing access to prevent unauthorized or undesired entry. Physical security includes human resources (such as law enforcement), hardware (doors and locks), and electronics (video and electronic access control).

Security cannot be implemented without costs, and security can never eliminate all risks. A balance must be struck to provide a reasonable degree of protection within a sustainable budget. While partial physical security measures can provide some value, security is best achieved with a layered approach. Physical access controls for protected facilities are generally intended to:

• Deter potential intruders (e.g., warning signs and perimeter markings)

• Distinguish authorized from unauthorized people (e.g., using badges and keys)

• Delay, frustrate and ideally prevent intrusion attempts (e.g., minimal number of entrances, law enforcement presence, and door locks)

• Detect intrusions and monitor/record intruders (e.g., intruder alarms and video surveillance systems)

• Trigger appropriate incident responses (e.g., by security and law enforcement).

The tried and true method of evaluating a facility’s security is through a security vulnerability assessment. In some states, these are called safety audits or just security assessments. These assessments should help to identify security strengths and vulnerabilities. At SafePlans, we use our web-based Emergency Response Information Portal (www.safeplans.com/about-ERIP) to conduct and manage these assessments. No matter how the assessments are completed, they need to be comprehensive and the party conducting the assessment needs to be an honest broker.

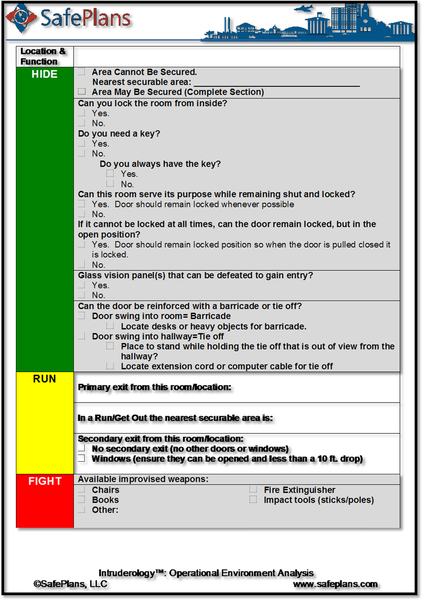

The exact questions in the assessments vary, but in general terms they should touch on the following (Figure 5.3):

– Grounds and Location

– Perimeter

– Exterior Doors and Entrance Ways

– Trailers/Portable Classrooms

– Buses, Drop Off and Parking Areas

– Stadiums & Recreations Areas

• Building Interior

– Surveillance

– Communications

– School-Based Law Enforcement and Security

– Visitor Procedures

– Building Layout and Construction

– Cafeteria

– Gymnasium

– Science Lab

– Materials/Supplies

– Specialized Areas

– Hallways and Stairs

– Restrooms

• Policy

– Emergency Operations Plan and Training

– Specific Procedures for Core Emergencies

– Drills

– Parental Reunification

– School Code of Conduct

– Information Security

– Staff and Student Training

– Health Practices

– Outsourcing of Security

– School Climate Interview (Bullying)

Since the Sandy Hook Elementary shooting, more schools are considering physical security updates, especially to main entrances. When considering the overarching security plan for any campus, Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED) is a great place to start. CPTED has been around since 1970s and while the term was coined by criminologist C. Ray Jeffery, the principles in practice today are a combination of multidisciplinary efforts. Some key components of CPTED that related to more secure entrances include:

Natural surveillance

People are less likely to commit crimes if they feel they are being observed. Natural surveillance involves designing features to maximize the visibility of areas that should be observed.

Access control

Limiting and regulating entrances reduces opportunities for crime and allows for more efficient screening of persons entering a facility.

Territoriality

Clear delineation of space creates a sense of ownership for legitimate users (staff and students) and creates an environment where intruders are more likely to standout.

CPTED is much broader than these three basic concepts, but they do serve as a strong basis for creating more secure entrances.

Eleven components of more secure school entrances

These 11 items are not a guarantee against forced entry, and a secured main entrance does not a safe school make. Just as there are other elements of CPTED and physical security, there are other considerations, beyond active shooters, that schools must consider when developing security plans and all-hazards emergency plans. It is also important to note that these recommendations do not include the assignment of personnel, such as law enforcement or security.

A full-site security assessment or safety audit is the most effective way to identify security-related strengths and weaknesses of your campus. This assessment should serve as the basis for short- and long-term enhancements. School districts and/or large campuses should implement a standardized assessment process for all facilities in order to prioritize recommendations based on vulnerabilities.

Consider unintended consequences and coordinate all security and emergency planning efforts with and by local public safety agencies. Implementing a new access control system may keep intruders out, but it can also make it difficult for law enforcement to gain rapid entry. The benefits of better access control easily outweigh the highly manageable risk of delaying law enforcement, but a degree of planning is required.

1. Perimeter fencing to deter trespass and limit access to non-primary entrances.

Fencing should encourage entry via highly visible and well-monitored areas, preferably those that are under video surveillance. While fencing does not prevent unauthorized access, it does make persons approaching the facility from undesired areas more obvious (Figure 5.4). The Secret Service will, at times, use theater-style ropes to block off an area. Obviously, a would-be attacker could easily cross the rope line. However, this act would draw the attention of the agents. People should have to make some effort and announce their presence if they enter your perimeter.

2. Single point of entry.

Effective access control requires that entry to and from a facility be regulated. A single point of entry allows for such monitoring. Efforts to mitigate forced entry via the primary entrance are marginalized if secondary points of entry are unsecure or easily defeated.

Some buildings require multiple points of entry. That is understandable; just realize that all points of entry must be regulated. For a point of entry to be regulated, no unauthorized person should pass through without drawing the attention of those responsible for the safety of the building.

If you cannot regulate all entrances, measures must be taken to regulate access at the campus level (extending the security perimeter) while ensuring each classroom operates with locked doors. Sites that cannot regulate access must be given priority when considering assignment of law enforcement or security personnel.

3. Staff monitoring of arrival and dismissal times.

Arrival and dismissal times require a lower security posture due to the volume of student and staff movement. Properly trained and equipped staff must be assigned to monitor activities during these periods. This requires training on intruder response, reverse evacuation, and how to assist in the arrival of public safety vehicles. Staff should be equipped with a radio to communicate with building/office staff and a phone for calling 911.

4. Strong visitor management program.

Regulating access to a school requires sound visitor management procedures. At a minimum, visitors should not be able to enter the school without registering at the main office. This should require proof of identification and the issuance of a visitor badge, and visitors should be escorted.

Visitor management programs should include prominent signage on all building entrances (Figure 5.5), visitor parking areas, and even parking lot entrances. Let visitors know your expectations.

5. Use of a vestibule/double entry system.

The intercom/video call box is located outside the school. Visitors are granted access upon approval from the main office. Ideally, visitors granted access through the primary entrance are required to pass through the main office (Figure 5.6). The office would allow visitors to enter the first entrance but the secondary entrance would remain locked.

6. Minimal glass.

Large windows and vision panels, while visually attractive, are easily defeated. Minimizing glass presents a more secure image and makes forced entry more difficult (Figure 5.7). General guidelines for the use of glass in main entrances are:

(a) Full windows should be a minimum 72″ off ground.

(b) Narrow windows/vision panels, below 72″ should be a maximum 12″ wide.

(c) Install security window film to reinforce glass on main entrances.

7. Electronic Access Control (EAC).

In its simplest form, an EAC system consists of an electronic door lock and some form of electronic verification device. The verification device can be an entry pad, card reader, biometric scanner, or even a video camera. Once a predefined criterion is met (i.e., a code is entered or a secretary looks at the screen and recognizes the person) the verification device communicates with the electronic door lock to allow entry.

The use of EAC will allow desired users, such as staff with proper access rights, to utilize the entrance without authorization from the main office. It is critical to coordinate with local public safety to ensure they have proper access rights and capabilities.

8. Video intercoms for visitor screening.

A video intercom system allows staff to see and talk with visitors before admitting them into the secured school. By determining a visitor’s identity before unlocking the door, staff can avoid face-to-face confrontations with a possibly dangerous individual.

Staff responsible for this preliminary security screening requires the backing of leadership. They need to know they are expected to ask questions and have the obligation to delay or even deny access to the school if they are not 100% certain the person does not pose a risk.

9. Door hardware.

The center mullion is the vertical element between double doors. A sturdy center mullion is vital to the integrity of locked doors. Door handles and push bars should be flush with the door to prevent them from being tied together to delay law enforcement or prevent emergency egress.

10. Panic button in office.

Panic or duress buttons (Figure 5.8) make it easier for school staff to notify law enforcement than calling 911 and allow more communication efforts to be directed toward safeguarding students.

If your school is totally dependent upon front office staff to provide notification of an intruder situation, consider expanding the panic button to a full intruder alarm that broadcasts a unique warning to the entire school.

11. Situational awareness

Not all elements of security rely on CPTED or hardware. Situational awareness is the ability to identify, process, and comprehend the critical elements of information about what is happening around you. This generally provides greater opportunities to prevent or at least mitigate the threat.

Situational awareness is an attitude, not a hard skill. It is something we all have some of the time and something none of us has all of the time. Jeff Cooper pioneered the concept of levels of situational awareness. Cooper was a marine and innovator of tactical training. He developed a color code system to illustrate levels of alertness. This system is called Cooper’s Color Codes (Table 5.3) and it has been used to train military and law enforcement personnel for decades.

Table 5.3

Cooper’s Color Codes

| White | Unprepared and unready |

| Yellow | Prepared, alert and relaxed. Good situational awareness |

| Orange | Specific alert to probably danger. Ready to take action |

| Red | Action Mode. Totally committed to the emergency at hand |

| Black | System overload. Total breakdown of physical and mental performance |

Situational awareness is a key element in intruder response. The following hypothetical example illustrates the value of situational awareness:

A person is going to a school to commit carry out an attack. You cannot change that he is coming, but you can determine when you observe his intent. When would you want to make this observation?

At the parking lot or at the front door? The front door or the hallway?

Hallway or classroom?

The sooner you are aware of the danger, the more time and options you have to respond.

Preparedness

The FEMA definition of preparedness (Figure 5.9) is:

A continuous cycle of planning, organizing, training, equipping, exercising, evaluating, and taking corrective action in an effort to ensure effective coordination during incident response.5

The Preparedness phase includes actions that will improve your chances of successfully dealing with an emergency. As noted in FEMA’s definition, preparedness is a continuous cycle of planning, organizing, training, equipping, exercising, evaluation, and improvement activities to ensure effective coordination and the enhancement of capabilities to prevent, protect against, respond to, recover from, and mitigate the effects of natural disasters, acts of terrorism, and other man-made disasters.

All-Hazards Plans

While active shooter events are rare, more students have died from acts of violence in U.S. K-12 schools over the last 50 years than have died from bus crashes, fires, and severe weather events in U.S. schools combined. Schools absolutely need all-hazards plans, but these plans must contain robust plans to address human-based threats and violent intruders.

Run/Hide/Fight

If you are ever confronted with a violent intruder or active shooter situation, you will need a plan. While no plan can totally protect schools, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) provides a three-option approach. The options are Run, Hide, and as a last resort, Fight.

As mentioned earlier, lockdown is simply compartmentalization and denying access. Lockdown is a valid security concept, but a lockdown cannot help those having direct contact with an attacker of those in areas that cannot be secured. A lockdown falls under the Hide category and is a component of intruder response, but a lockdown does not help those at the point of the attack—those at the greatest risk.

The good news about compartmentalization is that an attacker cannot be everywhere. If the threat is in the cafeteria, compartmentalizing students in classrooms may well be the best response. A lockdown should be viewed as an element of the Hide response, not as your only option.

Applying Run-Hide-Fight

Run-Hide-Fight is not a linear progression. A misperception of Run-Hide-Fight is that Run is always your first option. Going back to the shooter in the cafeteria scenario, while the students in the cafeteria should be directed to run, students in classrooms may need to implement a hide. Response is based on two key factors: your proximity to the threat (contact) and your location.

![]()

Contact

The most critical element in determining your response to an active shooter is your proximity to the threat—what’s between you and the attacker. Proximity is divided into two types:

• Direct Contact. There are no barriers between your location and the intruder and the intruder is close enough to pose an immediate danger.

• Indirect Contact. The intruder is inside or near your facility/general area but distance or barriers delay the intruder’s ability to harm you.

Location

The next important considerations address your abilities to secure your location and to escape. Obviously there are many different types of locations where attacks can occur; and this chapter classifies all locations into two types—securable and nonsecurable locations:

• Securable Location. A location that can provide a degree of protection from an intruder. This includes rooms with doors that may be secured and has minimal interior windows from the hallway to the room. A securable location is conducive to a Hide or lockdown response. (Note for more rural areas [response time over 5 minutes]: For a location to be deemed securable, it should be able to deny entry for as long as it will take law enforcement to arrive. School planners must coordinate with local law enforcement to estimate response times and analyze the ability to secure rooms.)

• Nonsecurable Location. A location that offers no protection from an intruder. This includes hallways or common spaces that do not have doors that could be secured. A nonsecurable location does not deny access and is not conducive to a Hide.

General Intruder Response Guidelines

No plan can cover every scenario. Run-Hide-Fight should be viewed as options (Figure 5.10). Only the exact scenario, your level of contact, and your location can determine your best response (Contact + Location = Response).

Run

Initiate a running evacuation when:

• You have direct contact with the intruder.

• You cannot lock the intruder out of your location.

Hide

Barricade or secure your area to delay the intruder if:

• You have indirect contact with the intruder.

• You can deny access/stop the intruder from entering.

Fight

As a last resort, when lives are in immediate danger, FIGHT if:

• You have direct contact, and you are in fear for your safety or the safety of others.

• You CANNOT RUN.

SafePlans does not recommend training K-12 students in the Fight option. As with any emergency, schools should prepare themselves on how to provide best direction and control over their students should Fight be required. Some students are physically capable of assisting, but the amount of time needed to train students on when to Fight is not easily justified by the risk. Training students in Run and Hide greatly improves upon the basic lockdown, making a Fight scenario even less likely.

Run

One of the most common questions about Run/Hide/Fight is whether the entire school should always try to run or evacuate as a first response to a violent intruder or active shooter. The short answer is: No.

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) presents Run-Hide-Fight as individual options, not building-wide action plans. When presenting Run (or evacuate) (Figure 5.11), DHS says to try and evacuate if there is an accessible escape path. A hallway packed with students (and a possible killer) may not be a path of escape. At a minimum it is never always a path of escape.

During an active shooter attack, some people inside the school will likely need to implement Run. However, a building-wide strategy to Run is only slightly better than a building-wide strategy to Hide (lockdown).

It is understandable why many want to provide one simple instruction in response to a violent intruder. Building-wide action steps work for fire (evacuate) or severe weather (shelter in place), but intruder response plans must have options. Remember, Run-Hide-Fight are options, not a linear system. During an active shooter event, persons in different locations will experience circumstances that require them to implement different actions. For instance, if there is a violent intruder in the cafeteria, Run would be the best response for those in the cafeteria (direct contact). At the same time, the best response for teacher in a classroom (indirect contact) may be to Hide by locking or even barricading the classroom door.

The level of contact with the attacker and the staff member’s location determines the best response—not an intercom announcement or mass message. Remember: Contact + Location = Response.

While one-size-fits-all responses are convenient, they simply do not provide occupants the maximum opportunity to survive.

Hide

The Hide option should be viewed as an active response. In a Hide situation you are trying to deny the attacker access to you and others. A Hide response (Figure 5.12) is not simply hide and seek. It is like hide and seek with no rules. Lock doors whenever you can, but even if you cannot lock doors, there are still ways to deny entry. This is called impromptu target hardening and it can save your life. Embrace your inner MacGyver and deny entry!

If you are in an area where you cannot deny entry, such as a hallway or area with no doors, you should strongly consider implementing the Run response and make every effort to avoid contact with the intruder. Trying to hide under tables or behind curtains may not make you safer. It will create a passive and stationary target for the attacker. Stationary targets are easier to shoot and more likely to receive fatal wounds. Again, if you cannot deny entry, strongly consider the Run option and avoid contact with the attacker.

Barricade

Doors that open inward are typically easy to barricade. A barricade may prevent the door from being opened (Figure 5.13). Place heavy objects in front of the door and never use your body to support the barricade. The contents of the room will likely determine the success of a barricade.

Blockade

For doors that open outward, you may be able to place a blockade in the doorway. Place heavy objects in doorway and never use your body to support the blockade (Figure 5.14). While the intruder may be able to open the door, he will have to contend with the blockade. The contents of the room will likely determine the success of a blockade.

Tie Off

Tie off the door by looping a belt, computer cable, or extension cord (or keep 20 ft of 550/Para cord in your desk) around the door handle. Either tie off to a solid fixed object or pull the door closed (Figure 5.15). Your size and strength may not be enough—so get help.

Fight

Violent intruders are very rare and the Hide and Run options greatly improve upon the basic lockdown. However, when it is not possible to Run or Hide, you must Fight (Figure 5.16) back against the attacker. The Fight option is about resisting and not allowing the attacker to have access to passive targets that are easy to shoot and kill. The Fight option is not grabbing a chair and running down a hallway to find the shooter. The Fight option is the last resort of resisting with physical aggression to protect lives when you cannot Run or deny access (Hide).

When fighting back, it is possible that people will be injured or even killed. However, if you do nothing, it is likely that more people will be injured and killed.

When you must Fight, remember the following:

• Lead others to help.

• Provide clear and confident instructions.

• Use improvised weapons, such as fire extinguishers, chairs, and books.

• Act with aggression until the threat is incapacitated.

When law enforcement arrives on the scene, remember:

• Their response to an intruder situation is focused on locating and neutralizing the threat.

• DO NOT leave a secure area to approach responders.

• All persons may be treated as suspects until determined otherwise.

• Keep hands raised, with your fingers spread.

• Do not make sudden movements.

• Follow law enforcement commands.

• Provide detailed information as appropriate.

Operational Environment Analysis

Now that you understand the basic Run-Hide-Fight options, becoming more familiar with your environment will help improve response efficiency. An operational environment analysis is a simple approach to gaining a better understanding of your Run-Hide-Fight options. Every principal should be able to explain how to apply Run-Hide-Fight in every area of his or her school. Teachers should be able to explain Run-Hide-Fight in his or her classroom, hallways, and common areas.

Figure 5.17 shows the K-12 Operational Environment Analysis form we use at SafePlans.

Response

The FEMA definition of response (Figure 5.18) is:

Activities that address the short-term, direct effects of an incident. Response includes immediate actions to save lives, protect property, and meet basic human needs.6

Organizational response to any significant disaster—natural or terrorist-borne—is based on existing emergency management organizational systems and processes. There is a need for both discipline (structure, doctrine, process) and agility (creativity, improvisation, adaptability) in responding to a disaster.

Emergency plans help educators prepare for and manage critical incidents. However, no emergency plan can cover every possible scenario. Ideally, training programs simulate real emergencies. But too often schools train to do extremely well under reasonable conditions—rather than training to perform reasonably well under extreme conditions. Real emergencies are extreme conditions, and when they occur, the ability to make sound decisions rapidly is imperative.

A valuable system in understanding the importance of proper timely decisions in a critical incident is the Observe-Orient-Decide-Act (OODA) loop (sometimes referred to as Boyd’s Cycle after its creator, retired U.S. Air Force Col. John Boyd) (Figure 5.19). Being a student of and expert on tactical operations, Boyd detailed that in many of the battles, when one side is not able to keep up with the ever-changing dynamics of a combat situation, that slower-to-react side was almost always defeated. In observing this, Boyd concluded that timely decision making is critically important and applied the phrase “time-competitive.”

According to Boyd’s theory, emergency response can be seen as a series of time-competitive, OODA cycles. Response begins by observing the overall situation. Orientation is next. Orientation is critical because the dynamic nature of an emergency makes it impossible to process information as quickly as it is observed. Orientation can be thought of as a snapshot approach to obtaining perspective. Once orientation is gained, it is time to decide. The decision considers all factors that were present during the orientation phase. Lastly, the final process is to act on the decision.

The “loop” occurs when our actions have changed the situation. The cycle continues throughout an incident.

Observe

The earlier you can observe someone intending to harm you or others, the greater your opportunity to survive. Observations can be visual or audible, anything that alerts you to possible danger. This ties into situational awareness mentioned earlier in this chapter.

Orient

Orientation is about making the best connection between your observations and your response options. Unfortunately, the more immediate the threat, the faster you must orient. Fortunately, in an active shooter situation response options are Run, Hide, and Fight. Orientation to which response is most appropriate is based on your level of contact with the intruder and your location.

Decide

Your decision is based on what you observe and how you orient those observations to your environment and abilities. For those not in direct contact with the shooter, and in a room that can be secured by a locked or barricaded door, Hide is typically the best response. If you are in an area that cannot be secured and you are not being attacked, you should Run to an area that offers safety. Persons in direct contact cannot Hide from the shooter. They must either Run or, if running is not an option, Fight as a last resort.

Act

Once the decision is made, it is time to act. Have confidence in knowing your actions are based on the best information available. Do not second-guess yourself, but have the presence of mind to repeat the OODA loop as your observations change. For instance, if you have to Fight as a last resort and the shooter flees, your OODA analysis may very well be to disengage and retreat to a safer area. Conversely, if you decide to Hide in a room and the shooter attempts to defeat the locked or barricaded door, an OODA analysis would prepare you to Run or Fight (Figure 5.20).

Recovery

The FEMA definition of Recovery (Figure 5.21) is:

Encompasses both short-term and long-term efforts for the rebuilding and revitalization of affected communities.7

The aim of the recovery phase is to restore the affected area to its previous state. It differs from the response phase in its focus; recovery efforts are concerned with issues and decisions that must be made after immediate needs are addressed.

Planning for recovery is conducted in the Preparedness phase and involves establishing key community partnerships, developing policies, providing training, and developing memorandums of understanding between agencies. Recovery is a vital component of an all-hazards emergency. Certain aspects of recovery are more pertinent to intruder-based events. These include:

• Return to the “business of learning” as quickly as possible.

• Schools and districts need to keep students, families, and the media informed.

• Provide assessment of emotional needs of staff, students, families, and responders.

• Provide stress management during class time.

• Conduct daily debriefings for staff, responders, and others assisting in recovery.

• Take as much time as needed for recovery.

• Remember anniversaries.

• Implement a system to manage receipt of donations.

• Establish locations for storing and strategies for delivering.

• Determine what donations will be accepted—for example, gift cards.

Major categories for recovery are:

• Mental Health Programs

• Family Reunification

• Business Resumption

Resources

While most school districts have adequate resources to meet daily operations, they are not sufficient to deal with an active shooter incident. It is important to document agreements for services that aid disaster response and recovery efforts. Memorandums of understanding (MOU) and mutual aid agreements (MAA) should be implemented in recovery plans. Note that MOUs should be completed with all agencies or facilities that will assist, but expect nothing in return.

Examples:

• An area transportation system agrees to aid in transporting students under extenuating circumstances.

• A local church agrees to provide shelter and basic relief services.

• The local Department of Mental Health agrees to aid in post-disaster counseling.

At the same time, MAAs should be completed for agencies or facilities that will assist schools, and do expect a reciprocal agreement for aid.

Example:

• A nearby church agrees to serve as an off-campus shelter but requests the school provide a location to evacuate their daycare in return.

Mental Health

Mental health must be considered in each phase and should be a part of each school’s plan and the overall district plan. At a minimum, each district should have a crisis intervention team (CIT) that operates and coordinates district-appointed teams. The crisis intervention team addresses the emotional needs of the students and staff. In that capacity, the team must be able to make rapid assessments of student and staff needs, provide family outreach, plan and carry out appropriate interventions, use individual and group strategies, and make referrals to mental health resources as appropriate. The team is also a key component of the school threat assessment process, helping to identify those who pose a threat to themselves or others, then helping to develop appropriate interventions and responses.

The objectives of crisis intervention are:

• BEFORE THE DISASTER/CRITICAL EVENT:

• Identify, monitor, and support at-risk students and staff.

• Develop ties with mental health and other community resources that support the emotional well-being of children.

• DURING THE DISASTER/CRITICAL EVENT:

• Protect—children by shielding them from:

- Exposure to traumatic stimuli (sights, sounds, smells)

- Media exposure

• Direct—ambulatory students who are in shock and dissociative:

- Using kind and firm instruction

- Away from danger, destruction, and the severely injured

• Connect

- To you as a supportive presence

- To caregivers

- To accurate information

• Triage for signs of stress that jeopardize safety.

• Segregate survivors based on exposure level.

• As appropriate, activate the Regional Homeland Security Mental Health Response System.

• Begin psychological first aid, including the work to reestablish the perception of security and sense of power.

• AFTER THE DISASTER/CRITICAL EVENT:

• Reunite students with caregivers as soon as possible.

• Reestablish a calm routine.

• Restore the learning environment.

• Continue with psychological first aid.

• Provide responsive crisis and grief counseling.

• Initiate referrals to mental health professionals.

• Provide information and psychoeducational materials to families and caregivers.

• Assist in community efforts to provide support for families.

The CIT team may be made up of individuals from a range of school staff who meet the above criteria, including: school counselors, psychologists, social workers, nurses, teachers, special education professionals, language learners, resource officers, or other law enforcement. Also consider that some maintenance and dietary staff form a special bond with students and may be willing to be trained and act in this capacity. This team will be led by a knowledgeable school-based mental health professional, such as the school counselor, social worker, or psychologist.

Timely identification and intervention with students experiencing academic, social, and behavioral difficulty is an integral part of the mitigation effort. Mitigation supports efforts to prevent or reduce violence against self and others.

The CIT will also develop ties with professional mental health resources in the area.

Organizations that provide mental health resources that the district should consider include:

• Supporting schools and neighboring school district teams

• Local community mental health centers

• Local college and university resources

• Private mental health agencies

• Chaplains and pastors with the appropriate training

• NOVA, the National Organization of Victim Assistance:

• Contact information for the national NOVA headquarters in Washington, DC, is [email protected] or 202-232-6682. NOVA services include:

- Immediate assistance within 24 hours

- Planning coordination with emergency responders

- On-site, one-to-one companioning

- On-site community group crisis intervention

The CIT should establish a family assistance center during major catastrophes. A central location provides both a community resource and a focal point for friends and family, relieving response agencies to do their jobs. CIT team members take on information liaison, mental health, and assistance functions in a controlled environment. Friends and families receive continuing updates on rescue or recovery efforts, as well as other information like family companioning, assistance visiting the disaster site, crisis intervention, mental health referrals, assistance filing for victim compensation, assistance with emergency financial needs, and assistance with forms to expedite death certification.

A family assistance center may exist long after a crisis is over, depending on the magnitude of the event. In the aftermath of a hurricane or tornado, where the missing may be counted in thousands, mental health, grieving, and personal paperwork issues could exist for months.

Family Reunification Functions

Throughout crisis evolution the school community is more or less engaged, some up close and some from afar, like parents at home. There is a continuing need for crisis response teams and school administration to track every individual student or staff member, and their community support system, from beginning of the event through to each person’s ability to resume education activities. Family reunification functions include the following:

1. Safe evacuation and full accountability of staff and students.

• Alert students and staff of evacuation.

• Evacuation of the school.

• Accountability of students after evacuation.

• Establish bus staging and loading areas.

• Move and load students and staff onto buses.

2. Establishing and carrying out a full relocation and reunification process.

• Alert and notification of the reunification team.

• Notification of parents, guardians, and media.

• Establish and set up the relocation site.

• Complete a reunification process.

• Test grief counseling team.

• Test first aid team.

• Test ability to handle special needs students.

3. Activation of a school District level EOC to coordinate these activities.

• Establish the emergency operations center (EOC), proper coordination, and tracking of status of events.

• Coordinate through Response, Reunification, and Recovery.

Business Resumption

The following points reflect the priorities, purpose, assumptions, and necessities of the business resumption process (getting the business back up and running normally).

• Secure critical infrastructure and facilities.

• Resume operations.

Purpose

• Provide for continued performance of essential functions under all circumstances.

• Ensure survivability of critical equipment, records, and other assets.

• Minimize business damage and losses.

• Achieve orderly response and recovery from the emergency.

• Ensure succession of key leadership.

• Serve as a foundation for overall program.

• Ensure survivability of the mission in most severe events.

Assumptions

• Access to buildings may be delayed or limited.

• The response and investigation process alone could take weeks (worst case).

• Cleanup and repairs could take much longer.

• You may be unable to enter your facility for an extended period of time.

Necessities

• Care of students and faculty.

• Locating temporary space.

• Computing infrastructure.

• Communications protocol.