Security Assessments and Prevention for K-12 Schools

Linda Watson, M.A., CPP, CSC, CHS-V Principal, independent security consultant, Whirlaway Group LLC

Abstract

This chapter explains how school security assessments are important for the safety and security of the over 80 million people involved in our schools (students and staff). The chapter shows the reader that a security assessment will identify both internal and external threats. It also reviews the importance of involving stakeholders from multiple areas in identifying threats.

Introduction

Our nation’s children are welcomed into their schools every day by their teachers and staff. Our educators are focused on educating their students in a safe and secure environment which allows their students to excel. However, safety has become a very complex issue in our schools. Deadly shootings at Columbine, Virginia Tech, and Sandy Hook, to name only a few, have significantly impacted our schools. School shootings are still a rare event, but an event that must be prepared for nevertheless. The sheer number of people who are affected by school safety is compelling:

“As of fall 2010 approximately 75.9 million people were projected as enrolled in public and private schools at all levels including elementary, secondary, and postsecondary degree-granting. In addition, the number of professional, administrative, and support staff employed in educational institutions was projected at 5.4 million.” (U.S. Department of Education 2010)1

Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design

School CPTED Survey/Assessment2

Crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED) is a concept that was first introduced in the 1970s. Timothy Crowe and Lawrence Fennelly provide the following definition of CPTED in their 2013 book, Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design:

A CPTED assessment attempts to evaluate the physical setting of facility and maintenance factors that affect the safety and crime quotient capability of a particular school. Environmental factors such as the types of neighborhoods, housing facilities, businesses, streets, and institutions surrounding the school affect the school’s operation.

Classrooms, security systems, lighting and color designs, accessibility, and quality of maintenance all evaluated to determine their effect on the school climate, natural supervision, defensible space, and differentiated space. The survey items are to be rated as satisfactory (S), unsatisfactory (U), or not applicable (NA).3

School CPTED Survey or Assessment4

A thorough CPTED survey should cover the following thirty points:

1. Poor visibility at entry to site

2. Easy vehicular access onto grounds

3. Off-site activity generator

4. Inadequate distance between school and neighbors

5. Easy-access hiding places

6. Area hidden by planting

7. School adjacent to traffic hazard

8. Portion of building inaccessible to emergency vehicles

9. Secluded hangout area

10. Vegetation hides part of the building

11. Site not visible from street

12. No barrier between parking and lawn

13. Gravel in parking area

14. Dangerous vehicular circulation

15. Enclosed courtyard conceals vandals

16. High parapet hides vandals

17. Trees located where visibility is required

18. Pedestrian-vehicle conflict

19. Structure provides hideout

20. Building walls subject to bouncing balls

21. Parts of bus shelter not visible

22. Mechanical equipment accessible

23. Stacked materials and downspouts provide roof access

24. Recessed entry obscures intruders

25. Portions of building not visible from vehicle areas

26. Walkway roof eases access to building roof

27. Recess hides vandals

28. Skylight proves easy access

29. Mechanical screen conceals vandals

30. Access through complex

Security CPTED Assessment

Conducting a security CPTED assessment or survey of a school starts with the physical security exterior areas described in the above security survey. Additionally, it is important to interview the stakeholders who work in the school. These stakeholders are the eyes and ears of the school and they can identify the problems which exist within their school.

Using an all-hazards approach will cover many of the natural events that are possible: fire, hurricane, tornado, earthquake, flood, or severe wind. Add in manmade events such as chemical, hazardous, and biological catastrophes, and you can see many of the threats to be considered. These events are more likely to occur than a school shooting or a terrorist attack. With the all-hazards approach, you prepare for all possible events versus “just” a school shooting or terrorist attack. An all-hazards approach is the approach that best serves every school, large or small, public or private.

A security assessment is a process of identifying the security risks that a school may be exposed to and how you will respond to them. When identifying risks you must decide if it is too costly to protect or replace an item(s). If that is the case, then you may choose to protect the existing item, but know if a loss occurs it will not be replaced. This is the basis of a security assessment: mitigation, preparedness, and response. Every school is unique and there is no one security assessment that fits every school. By speaking with the stakeholders you get to learn about the community and how the school fits into that community. As you identify the threats, you can then evaluate and rate the level of the threats to the school as a whole. Use a scale starting with very low (1) through very high (10). By rating the threats you are assessing the likelihood or credibility of a threat. These threats are evaluated on the type of loss or damage that would result from an event. This subject has been successfully covered in great detail in the book Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design, 3e by Timothy D. Crowe, revised by Lawrence Fennelly. We have attached two appendices to complement this chapter. Appendix A discusses ten key questions that should guide the assessment of a threat. The use of the Security Assessment/Survey in Appendix B will help you evaluate the interior and exterior of the school’s facility.

Much has been written on the methodologies of how to conduct and evaluate security assessments for school systems. There are many useful tools located on the U.S. Department of Education and American Clearinghouse on Educational Facilities websites.

It is important to emphasize how essential the physical security assessment is as the basis of all other security work. An assessment encourages you to evaluate the potential for internal threats within a school, and when evaluating these internal threats it is wise to look at the vulnerabilities within the school and evaluate “how” the school would be attacked. When you look at the security assessments from this perspective, your individual stakeholders can contribute regarding where they think an attack might be launched from. The internal threats may be a jilted lover or a recently fired employee who feels “wronged.” These potential threats are very dangerous because of the “actor’s” (the person who acts) intimate knowledge of the campus and the unique culture within the educational institution. These actors know all the rules of getting into and out of the campus buildings and where there are vulnerabilities they can exploit because they are a known face at a dorm or classroom complex.

When you look back at past violent school events we can see many patterns emerging within the events themselves. Lessons learned from past school shootings at Columbine, Virginia Tech, and Sandy Hook teach us how to improve our communications with students, visitors, staff, and faculty during an emerging critical event on campus. Unfortunately, the active shooters can also study the past attacks and may have learned from the mistakes of the past as well.

Many times after a tragic event on a school campus, people who have taught the student or were acquainted with the faculty member responsible for the attack say they noticed odd things prior to the event but did not think to report it to authorities. Having an independent reporting system in place that is widely advertised gives concerned persons the ability to report their observations without the fear of reprisals.

In his book, The Gift of Fear, Gavin de Becker discusses in great detail the cues that are usually present before an incident (pre-incident cues) but are often ignored by coworkers or faculty and staff. Many times after an event when the media is interviewing persons who knew the actor, a pattern of odd or unusual behavior emerges. However, many of these persons only know the actor in the context of school or work. They do not have the opportunity to compare notes with other parties who also know the actor in a different venue.

Tragedies

After the Columbine, Virginia Tech, and Sandy Hook tragedies we have learned that having a critical incident team (CIT) in place and ready to evaluate a potential at-risk student, faculty member or employee is very important. These teams focus on a holistic approach to evaluating the at-risk individual. The CIT can be composed of many different professionals: commonly there will be administrative, human resources, mental health, legal and law enforcement members. This diversity gives the team the opportunity to evaluate an at-risk person from their “specialty” and report back to their CIT peers with their findings.

In the past, communication was an issue if a student went before the student review board for a violation of some student infraction. Many times, the student review board did not pass their findings onto law enforcement or the mental health counselors. The advantage of a CIT is that they now have the ability to follow up on the student and make cross-department notes with other CIT peers. They are immediately getting involved and holistically evaluating the potential risks that are exhibited by an at-risk student.

In some past tragedies, family members have told the interviewing authorities that they were unaware of any issues involving their loved ones at school prior to the tragic event. With a CIT in place, they can get the family involved in evaluating and discussing their plans for how the student should proceed since the last known issue that has been brought to their attention.

Family members often say in hindsight that given the opportunity to get involved with their loved one they would have done whatever would have been helpful to defuse the situation and avoid the tragic event that occurred.

A review of many of the recent tragic events that have occurred at educational institutions reveals that many times there appears to have been a mental health issue that is only brought to the community’s attention after the incident. Children that have been bullied or attacked on social media after school have nowhere to hide now. Prior to smartphones and current technology, when a child got off the bus at the end of the day, they had a break from school until the next day. Now a child can connect 24/7 with their peers, which can cause them to feel that there is no escape from the harassment or bullying. Despite established rules designed to protect at-risk students from cyber bullying, many times the student does not disengage from social media when school ends.

The impact of being bullied or picked on can become enormous, forcing a student to withdraw from the school environment. Some students become isolated and may not have adequate parental supervision or a trusted adult who can help them engage in a healthy dialog with their peers. Some students react to bullying by acting out with violence.

Conclusion

In conclusion, security assessments for K-12 schools should also include a CIT component to evaluate the threats and risks to a school from internal threats. The emphasis in the past was on the facility and threats to that facility. This emphasis remains very important, but we now must look at internal threats such as the risk from students, visitors, vendors, and faculty or staff members. By having an open dialog across departments, the likelihood of thwarting an internal threat is much greater. People are your greatest asset and your greatest vulnerability.

Appendix A U.S. Secret Service Threat Assessment Suggestions

This appendix is reprinted from “Guide for Preventing and Responding to School Violence,” Bureau of Justice Assistance, 2007, page 18, Grant 2007-DD-BX-K112.

School and law enforcement officials are frequently placed in the difficult position of having to assess specific people (students, staff, teachers, and others) who may be likely to engage in targeted violence in which there is a known or knowable target or potential assailant. The following suggestions for threat assessment investigations are based on guidelines developed by the U.S. Secret Service’s National Threat Assessment Center (NTAC). They were developed primarily for preventing the assassination of public officials, so they may not be applicable to all school situations. To identify threats, school officials are advised to take the following steps:

1. Focus on individuals’ thinking and behavior as indicators of their progress on a pathway to violent actions. Avoid profiling or basing assumptions on sociopsychological characteristics. In reality, accurate profiles for those likely to commit acts of targeted violence do not exist. School shootings are infrequent and most people who happen to match a particular profile do not commit violent acts. In addition, many individuals who commit violent acts do not match profiles.

2. Focus on individuals who pose a threat, not only on those who explicitly communicate a threat. Many individuals who make direct threats do not pose an actual risk, while many people who ultimately commit acts of targeted violence never communicate threats to their targets. Before making an attack, potential aggressors may provide evidence they have engaged in thinking, planning, and logistical preparations. They may communicate their intentions to family, friends, or colleagues, or write about their plans in a diary or journal. They may have engaged in attack-related behaviors: deciding on a victim or set of victims, determining a time and approach to attack, and selecting a means of attack. They may have collected information about their intended targets and the setting of the attack as well as information about similar attacks that have previously occurred.

Once individuals who may pose a threat have been identified, 10 key questions should guide the assessment of the threat:

1. What motivated the individual to make the statement or take the action that caused him or her to come to attention?

2. What has the individual communicated to anyone concerning his or her intentions?

3. Has the individual shown an interest in targeted violence, perpetrators of targeted violence, weapons, extremist groups, or murder?

4. Has the individual engaged in attack-related behavior, including any menacing, harassing, or stalking-type behavior?

5. Does the individual have a history of mental illness involving command hallucinations, delusional ideas, feelings of persecution, and so on, with indications that the individual has acted on those beliefs?

6. How organized is the individual? Is he or she capable of developing and carrying out a plan?

7. Has the individual experienced a recent loss or loss of status, and has this led to feelings of desperation and despair?

8. Corroboration: What is the individual saying, and is it consistent with his or her actions?

9. Is there concern among those who know the individual that he or she might take action based on inappropriate ideas?

10. What factors in the individual’s life and environment might increase or decrease the likelihood of the individual attempting to attack a target?

Source: R. Fein and B. Vossekuil, National Threat Assessment Center, U.S. Secret Service.

Appendix B School Safety and Security Checklist

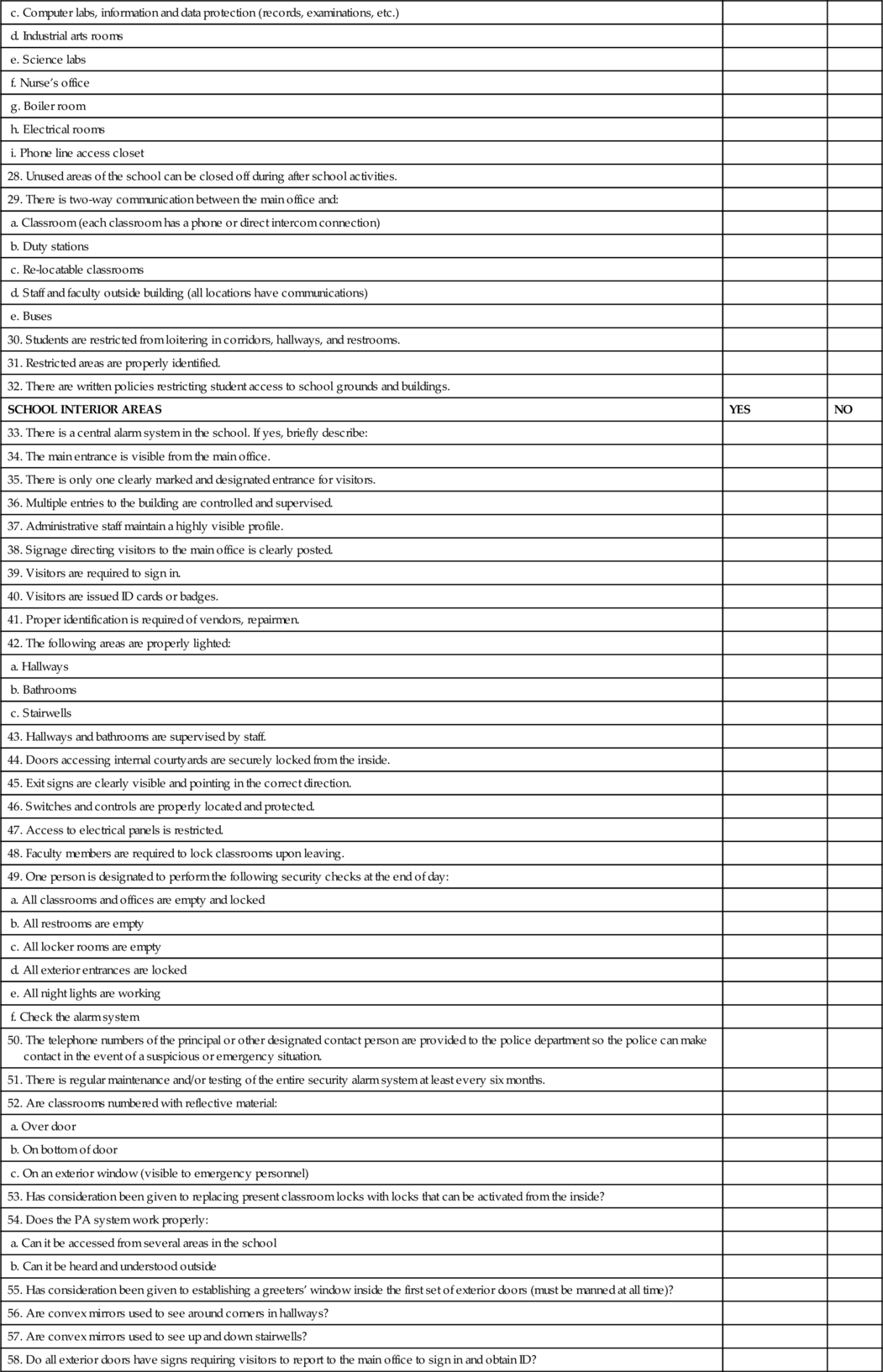

| SCHOOL SAFETY AND SECURITY CHECKLIST | ||

| School District: | School: | Address: |

| Team Members: | ||

| Date: | School Representative: | |

| Instructions: This checklist is designed to help evaluate the safety and security of your school. | ||

| The best way to use it is to form teams to conduct the survey at locations other than their own | ||

| to keep observations neutral and objective. Each survey team should ensure that local law and | ||

| fire personnel are invited to help with the evaluations and planning. Audit team members | ||

| should review the following documents and materials, preferably in advance of the onsite visit: | ||

| 1. Student / staff code of conduct | ||

| 2. Data on student discipline referrals | ||

| 3. Criminal data (reported by the school and by the surrounding community) | ||

| 4. Blueprint of the school | ||

| 5. Crisis management plan 6. Information and data protection (records, examinations, etc.) | ||

| The checklist does not take the place of crisis management plans or emergency plans but | ||

| supports the testing and adequacy of these plans. School safety and security requires policies | ||

| and procedures for management of disciplinary issues and dangerous students. | ||

| You can contact _________________________________, if you have questions or need | ||

| assistance at _______________________________. | ||

| SAFETY AND SECURITY TEAM NOTES | ||

| SCHOOL EXTERIOR AND PLAY AREAS | YES | NO |

| 1. School grounds are fenced. | ||

| 2. What kind? | ||

| 3. If yes, approximate height (security fencing should meet zoning and code standards. Best height prevents unauthorized entry and is 6-8 ft tall with a turned top to restrict scaling) Are gates secured by locks? | ||

| 4. There is one clearly marked and designated entrance for visitors. | ||

| 5. Signs are posted for visitors to report to main office through a designated entrance. | ||

| 6. Restricted areas are clearly marked. | ||

| 7. Shrubs and foliage are trimmed to allow for good line of sight (3'-0"/8'-0" rule). | ||

| 8. Shrubs near building have been trimmed “up” to allow view of bottom of building. | ||

| 9. Bus loading and drop-off zones are clearly defined. | ||

| 10. Access to bus loading area is restricted to other vehicles during loading/unloading. | ||

| 11. Staff is assigned to bus loading/drop off areas. | ||

| 12. There is a schedule for maintenance of: | ||

| a. Outside lights | ||

| b. Locks/hardware | ||

| c. Storage sheds | ||

| d. Windows | ||

| e. Other exterior buildings | ||

| 13. There is adequate lighting around the building. | ||

| 14. Lighting is provided at entrances and points of possible intrusion. | ||

| 15. Play areas are fenced. Visual surveillance of playground areas is possible from a single point. | ||

| 16. Playground equipment has tamper-proof fasteners. | ||

| 17. Visual surveillance of parking lots from main office is possible. | ||

| 18. Parking lot is lighted properly and all lights are functioning. | ||

| 19. All areas of school buildings and grounds are accessible to patrolling security vehicles. | ||

| 20. Students/staff are issued parking stickers for assigned parking areas. | ||

| 21. Student access to parking area is restricted to arrival and dismissal times. | ||

| 22. Staff and visitor parking has been designated. | ||

| 23. Outside hardware has been removed from all doors except at points of entry. | ||

| 24. Ground floor windows: | ||

| a. Broken panes | ||

| b. Locking hardware in working order | ||

| 25. Basement windows are protected with grill or well cover. | ||

| 26. Doors are locked when classrooms are vacant. | ||

| 27. High-risk areas are protected by high security locks and an alarm system | ||

| a. Main office | ||

| b. Cafeteria | ||

| c. Computer labs, information and data protection (records, examinations, etc.) | ||

| d. Industrial arts rooms | ||

| e. Science labs | ||

| f. Nurse’s office | ||

| g. Boiler room | ||

| h. Electrical rooms | ||

| i. Phone line access closet | ||

| 28. Unused areas of the school can be closed off during after school activities. | ||

| 29. There is two-way communication between the main office and: | ||

| a. Classroom (each classroom has a phone or direct intercom connection) | ||

| b. Duty stations | ||

| c. Re-locatable classrooms | ||

| d. Staff and faculty outside building (all locations have communications) | ||

| e. Buses | ||

| 30. Students are restricted from loitering in corridors, hallways, and restrooms. | ||

| 31. Restricted areas are properly identified. | ||

| 32. There are written policies restricting student access to school grounds and buildings. | ||

| SCHOOL INTERIOR AREAS | YES | NO |

| 33. There is a central alarm system in the school. If yes, briefly describe: | ||

| 34. The main entrance is visible from the main office. | ||

| 35. There is only one clearly marked and designated entrance for visitors. | ||

| 36. Multiple entries to the building are controlled and supervised. | ||

| 37. Administrative staff maintain a highly visible profile. | ||

| 38. Signage directing visitors to the main office is clearly posted. | ||

| 39. Visitors are required to sign in. | ||

| 40. Visitors are issued ID cards or badges. | ||

| 41. Proper identification is required of vendors, repairmen. | ||

| 42. The following areas are properly lighted: | ||

| a. Hallways | ||

| b. Bathrooms | ||

| c. Stairwells | ||

| 43. Hallways and bathrooms are supervised by staff. | ||

| 44. Doors accessing internal courtyards are securely locked from the inside. | ||

| 45. Exit signs are clearly visible and pointing in the correct direction. | ||

| 46. Switches and controls are properly located and protected. | ||

| 47. Access to electrical panels is restricted. | ||

| 48. Faculty members are required to lock classrooms upon leaving. | ||

| 49. One person is designated to perform the following security checks at the end of day: | ||

| a. All classrooms and offices are empty and locked | ||

| b. All restrooms are empty | ||

| c. All locker rooms are empty | ||

| d. All exterior entrances are locked | ||

| e. All night lights are working | ||

| f. Check the alarm system | ||

| 50. The telephone numbers of the principal or other designated contact person are provided to the police department so the police can make contact in the event of a suspicious or emergency situation. | ||

| 51. There is regular maintenance and/or testing of the entire security alarm system at least every six months. | ||

| 52. Are classrooms numbered with reflective material: | ||

| a. Over door | ||

| b. On bottom of door | ||

| c. On an exterior window (visible to emergency personnel) | ||

| 53. Has consideration been given to replacing present classroom locks with locks that can be activated from the inside? | ||

| 54. Does the PA system work properly: | ||

| a. Can it be accessed from several areas in the school | ||

| b. Can it be heard and understood outside | ||

| 55. Has consideration been given to establishing a greeters’ window inside the first set of exterior doors (must be manned at all time)? | ||

| 56. Are convex mirrors used to see around corners in hallways? | ||

| 57. Are convex mirrors used to see up and down stairwells? | ||

| 58. Do all exterior doors have signs requiring visitors to report to the main office to sign in and obtain ID? | ||

| 59. Has consideration been given to installing proximity readers on certain exterior doors? | ||

| 60. How do you communicate during emergencies: | ||

| a. Two-way radios | ||

| b. Cell phones | ||

| c. Pagers | ||

| d. Other | ||

| 61. Who is issued two-way radios: | ||

| a. Administrators | ||

| b. Custodians | ||

| c. Members of the emergency response team | ||

| d. Other | ||

| 62. There is a control system in place to monitor keys and duplicates. | ||

| 63. Mechanical rooms and hazardous storage areas are locked. | ||

| 64. Fire drills are conducted as required by law. | ||

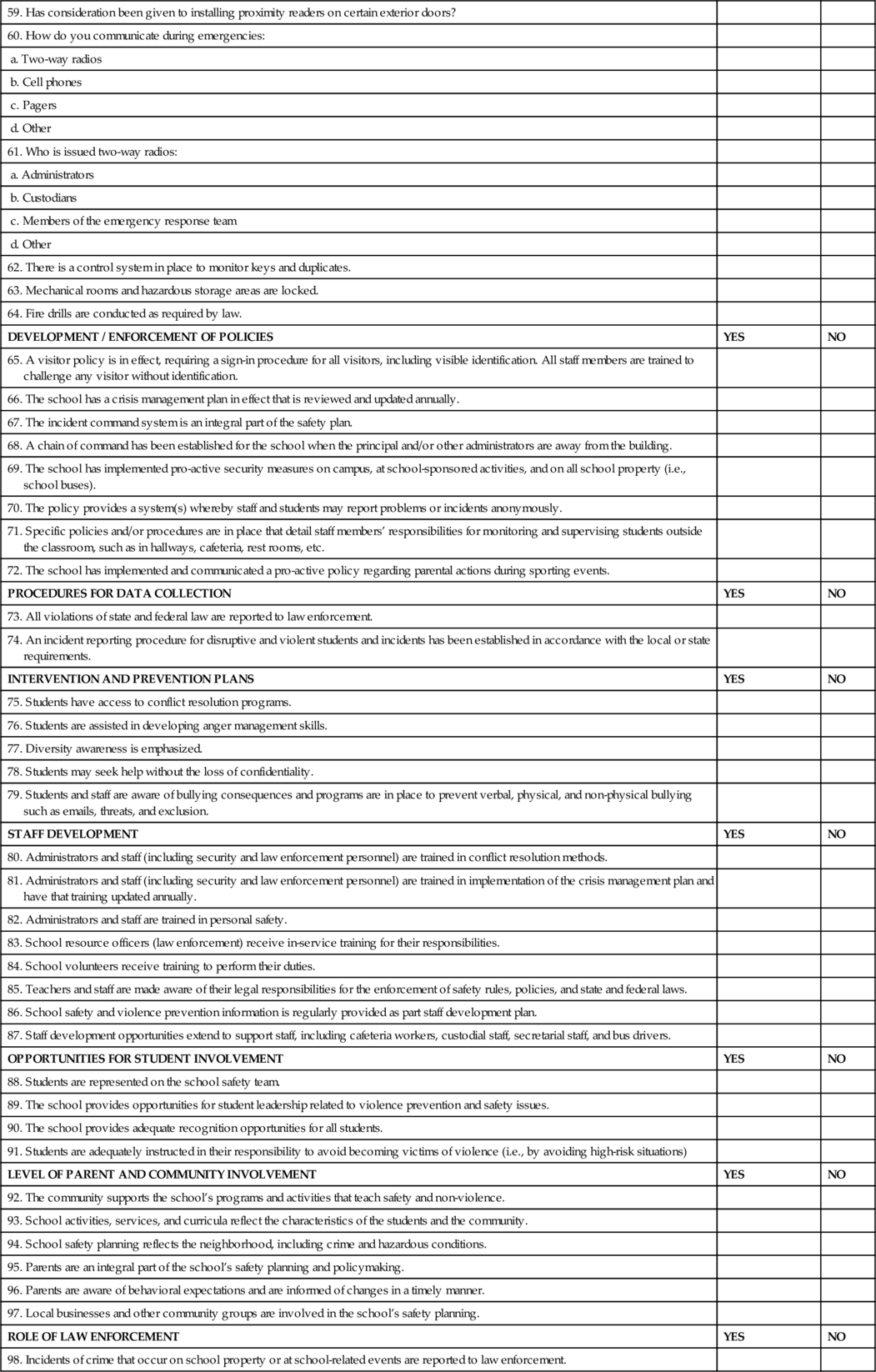

| DEVELOPMENT / ENFORCEMENT OF POLICIES | YES | NO |

| 65. A visitor policy is in effect, requiring a sign-in procedure for all visitors, including visible identification. All staff members are trained to challenge any visitor without identification. | ||

| 66. The school has a crisis management plan in effect that is reviewed and updated annually. | ||

| 67. The incident command system is an integral part of the safety plan. | ||

| 68. A chain of command has been established for the school when the principal and/or other administrators are away from the building. | ||

| 69. The school has implemented pro-active security measures on campus, at school-sponsored activities, and on all school property (i.e., school buses). | ||

| 70. The policy provides a system(s) whereby staff and students may report problems or incidents anonymously. | ||

| 71. Specific policies and/or procedures are in place that detail staff members’ responsibilities for monitoring and supervising students outside the classroom, such as in hallways, cafeteria, rest rooms, etc. | ||

| 72. The school has implemented and communicated a pro-active policy regarding parental actions during sporting events. | ||

| PROCEDURES FOR DATA COLLECTION | YES | NO |

| 73. All violations of state and federal law are reported to law enforcement. | ||

| 74. An incident reporting procedure for disruptive and violent students and incidents has been established in accordance with the local or state requirements. | ||

| INTERVENTION AND PREVENTION PLANS | YES | NO |

| 75. Students have access to conflict resolution programs. | ||

| 76. Students are assisted in developing anger management skills. | ||

| 77. Diversity awareness is emphasized. | ||

| 78. Students may seek help without the loss of confidentiality. | ||

| 79. Students and staff are aware of bullying consequences and programs are in place to prevent verbal, physical, and non-physical bullying such as emails, threats, and exclusion. | ||

| STAFF DEVELOPMENT | YES | NO |

| 80. Administrators and staff (including security and law enforcement personnel) are trained in conflict resolution methods. | ||

| 81. Administrators and staff (including security and law enforcement personnel) are trained in implementation of the crisis management plan and have that training updated annually. | ||

| 82. Administrators and staff are trained in personal safety. | ||

| 83. School resource officers (law enforcement) receive in-service training for their responsibilities. | ||

| 84. School volunteers receive training to perform their duties. | ||

| 85. Teachers and staff are made aware of their legal responsibilities for the enforcement of safety rules, policies, and state and federal laws. | ||

| 86. School safety and violence prevention information is regularly provided as part staff development plan. | ||

| 87. Staff development opportunities extend to support staff, including cafeteria workers, custodial staff, secretarial staff, and bus drivers. | ||

| OPPORTUNITIES FOR STUDENT INVOLVEMENT | YES | NO |

| 88. Students are represented on the school safety team. | ||

| 89. The school provides opportunities for student leadership related to violence prevention and safety issues. | ||

| 90. The school provides adequate recognition opportunities for all students. | ||

| 91. Students are adequately instructed in their responsibility to avoid becoming victims of violence (i.e., by avoiding high-risk situations) | ||

| LEVEL OF PARENT AND COMMUNITY INVOLVEMENT | YES | NO |

| 92. The community supports the school’s programs and activities that teach safety and non-violence. | ||

| 93. School activities, services, and curricula reflect the characteristics of the students and the community. | ||

| 94. School safety planning reflects the neighborhood, including crime and hazardous conditions. | ||

| 95. Parents are an integral part of the school’s safety planning and policymaking. | ||

| 96. Parents are aware of behavioral expectations and are informed of changes in a timely manner. | ||

| 97. Local businesses and other community groups are involved in the school’s safety planning. | ||

| ROLE OF LAW ENFORCEMENT | YES | NO |

| 98. Incidents of crime that occur on school property or at school-related events are reported to law enforcement. | ||

| 99. Law enforcement is consulted on matters that may fall below the threshold of criminal activity. | ||

| 100. Law enforcement personnel are an integral part of the school’s safety planning process. Law enforcement and fire departments have complete current campus maps, floor plans and diagrams showing the location and use of all rooms and critical materials such as chemicals and utility shut-off. Police and fire departments have had tours of the buildings and opportunities to familiarize themselves with the campus. | ||

| 101. The school and local law enforcement have developed a written agreement of understanding, defining the roles and responsibilities of both. | ||

| 102. Law enforcement personnel provide a visible presence on campus during school hours and at school-related events. | ||

| 103. Local law enforcement provides after-hours patrols of the school site. | ||

| DEVELOPMENT OF A CRISIS MANAGEMENT PLAN | YES | NO |

| 104. The school has a crisis management plan: | ||

| a. Reviewed on an annual basis | ||

| b. Developed by the building safety team and reviewed by management. | ||

| c. Team membership is open to all employees and student representatives | ||

| 105. The school has established a well-coordinated emergency plan with law enforcement and other crisis response agencies. | ||

| 106. Categories listed in the plan should include, but may not be limited to, the following: | ||

| a. Natural disasters | ||

| b. Accidents | ||

| c. Acts of violence | ||

| d. Death | ||

| e. Loss of power | ||

| f. Fire | ||

| g. Earthquake | ||

| SAFETY AND SECURITY TEAM NOTES | ||