Think on the margin

Focus on the next unit

The judgement of value refers only to the supply with which the concrete act of choice is concerned.

Ludwig von Mises

BENEFITS OF THIS MENTAL TACTIC

Thinking on the margin is a fundamental tactic for rational decision making. It requires you to only take into account variables that are pertinent to your situation (rather than those that are set in the past and hence unchangeable). In its core, marginal thinking is economic thinking, as it always assumes that decisions are made by weighing additional costs against additional benefits. We often fall into the all or nothing trap in which we consider all the benefits and all the costs of a decision situation, which not only renders them very complex (and computationally heavy), but also leads to flawed decisions.

When not to use this mental tactic

There are some situations in which making decisions on the margin is not sensible. Consider the fashion retailer Nordstrom, renowned for its laissez-faire return policy. Nordstrom’s customer satisfaction guarantee includes full reimbursement of returned products even without receipts, often years after the purchase. At the margin, Nordstrom shouldn’t accept these refunds: the marginal costs of paying refunds for used clothes that might be unsaleable results in a marginal net loss. But taking into account the reputational benefit of the liberal return policy, Nordstrom’s approach might lead to an increase in overall profits and greater customer satisfaction.

FOCUS ON THE NEXT UNIT

Suppose we offer you the choice between a glass of water and a bar of gold. What a question, you think. Of course, you’d choose gold over water. You have intuitively made a marginal decision. It’s likely that for you gold carries a much higher market value than water. But what if you were asked this question during a multi-day trip through the Sahara desert without any liquids? The bar of gold would have no value for you in this situation as all you long for is water.

How do you think on the margin? Marginal in this context means additional. By thinking on the margin, you are considering the effect the next additional (or incremental) unit has on you. For an Uber driver, the cost of earning an extra hour’s pay at the end of a long day is much higher than at the beginning of her their shift. They are tired and their back aches, which makes a marginal hour of driving at the end of their shift much more arduous.

It turns out that the price set for a product is, at least among neoclassical economists, exactly equal to its marginal utility. The marginal utility is the amount of satisfaction, pleasure or benefit people get out of consuming the next unit of it. So, it is not the fact that water in itself is abundant, but that the pleasure of consuming one unit of water for the typical person is lower than the pleasure that people take from a unit of gold. The reason being, most people are sufficiently hydrated in the given moment and, in most places, water is in ample supply. We can rely on our water systems working tomorrow just as they do today and we trust that supermarkets will continue to stock affordable bottles of water.

You may think: what’s the value of this chapter when I already intuitively make decisions on the margin? What extra value can it bring? Well, it turns out that most of us are actually really bad at thinking on the margin. We often take the past too much into account, either to tell a consistent story to ourselves, or because the past appears to be intimately linked to future decisions.

THE BUILDING BLOCKS OF MARGINAL THINKING

Marginal units

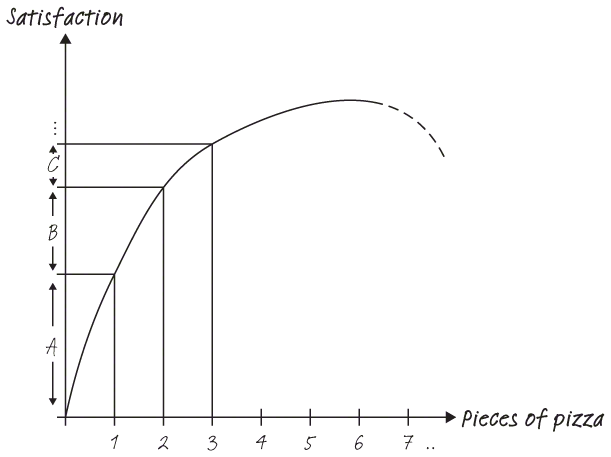

Instead of considering the total or average amount in every decision, the marginal thinker is only concerned with the additional unit, such as the next hour of driving, the next piece of pizza, or the next investment. One of the fascinating characteristics of marginal units is that they are what economists describe as typically decreasing in whatever input factor is required.

What does that mean? For example, take eating pizza. The first slice will be delicious, and so will the second, third and fourth. Soon you’ll be getting full, and the next (marginal) slice of pizza won’t be as satisfying as the first one. In the chart below, the vertical distance, measuring satisfaction (or, as an economist would term it ‘utility’) declines with each extra piece of pizza – eventually even turning negative.

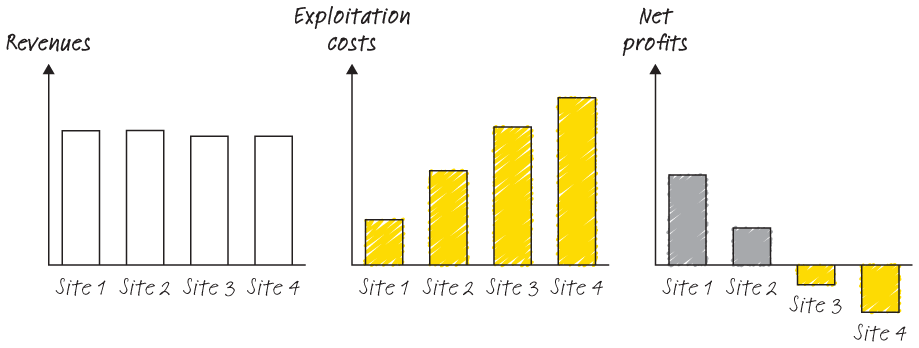

Or consider an energy company active in oil exploration. The first oil fields are easy to tap into as their location is known and their reservoirs are large and accessible (assume, to simplify, that all oil fields have oil reservoirs of equal sizes). Maximising their profits, the next (marginal) oil field project will be the ones that are slightly harder to access, and so on. At the end, the only fields that remain are those that are hardest to reach.

In the following chart are the expected exploitation costs and revenues for four oil fields. The lengths of the arrows indicate exploitation costs per site. The executive committee, acting on behalf of shareholders, would start with those projects promising highest profit first (oil field 1), and work their way downwards. The expected revenues of oil field 4 are below the exploitation costs, at least at the given moment. This may change as technology advances and then your marginal utility would change too.

Marginal thinkers ask themselves: “What’s the most value-adding activity I could spend my next five minutes on?”, “How can I put this $100 to best use?” or “Given the current customer base, which customer should we take care of next?”

Sunk costs

Sunk costs are costs that have been incurred as a result of past decisions. They are unrecoverable. Because they happened in the past, they are different from the other costs a company faces, such as R&D or materials. They are independent from any event in the future. Sunk costs have been incurred no matter what you choose to do next. They cannot be influenced.

Even though we talk about costs here, what is meant is any kind of outlay (time or attention) expended to bring about a better result in the future. A cost could be learning a skill, for example. Say you are told that an attractive business position opened up in Latin America. The deal is sealed, and in a year from now, you and your family plan to move to Mexico City. In anticipation of your new role, you invest many hours per week in learning Spanish. However, due to bad luck, the position in Mexico City falls flat. At this junction, it is natural for most of us to say to ourselves, “Well, I’ve already invested at least 200 hours in learning Spanish. I might as well make the most out of it and continue to practise it. You never know!”

But it is actually not the most rational thing to do, unless you really enjoy learning languages or anticipate that knowing Spanish will be advantageous to your future career or life. The fact that you have learned Spanish in the past should not in itself be enough reason to continue to do so. Assuming you don’t benefit in speaking Spanish in any other way, the costs of learning Spanish are sunk and unrecoverable. You simply can’t undo the past, or allocate the cost (your time spent practising) in any other way.

Humans tend to hold on too tightly to their past decisions and hence fall into the sunk cost fallacy. We do this because our mind subconsciously connects decisions that are related, even if they are in the past and don’t make a difference for future decisions. Marginal thinkers are only interested in the future outcomes of their decisions and future trade-offs. They don’t have any allegiance to whatever happened in the past.

How can you address this? Armed with The Decision Maker’s Playbook, you can take on a new role in your organisation: the sunk cost bias police. Whenever you hear someone saying something like, “We’ve already spent so much time on this” or “We spent a lot of money setting up the business in Angola,” you can be virtually certain that sunk cost bias is at work. We’ve found it helpful to respectfully but directly intervene at those moments by saying: “That’s actually not the point. That time and money is gone. The question is whether the next dollar or hour we are about to invest is worth it, knowing what you know right now.”

Decreasing marginal returns

This idea is key to marginal thinking. In fact, without decreasing marginal returns there would not be the need to think at the margin.

Decreasing marginal returns are ubiquitous in life. For example, fertiliser improves crop production, but only up to a point. The more fertiliser you add, the lower the impact produced per unit of fertiliser and overkill can even reduce the yield.

The same is also true of the satisfaction we get from activities. Riding a rollercoaster is fun for a few minutes, maybe even an hour. After that time, it quickly gets less exciting. Even the satisfaction of being on holiday, something most us look forward to more than anything else, doesn’t linearly increase with the duration of the holiday. It is fun to forget which week day it is during the first two weeks, sit at the pool, drink margaritas and live and let live, but after a while even this gets dull and one wishes to go back home (and potentially even back to work).

The same is true for the satisfaction we derive from income. We often imagine that more money is better, and that we cannot have too much of it. One of the best-known studies on the relationship between happiness and income levels was done by Betsey Stevenson and Justin Wolfers in 2013. On a life satisfaction scale from 0 to 10, doubling your income doesn’t translate into doubling your happiness. Rather, it buys you half a point on the scale. Stevenson and Wolfers illustrate this using an example: “GDP per capita in Burundi is about one-sixtieth that in the United States; hence a $100 rise in average income would have a twenty-fold larger impact on measured well-being in Burundi than in the United States.”53

Marginal thinkers are very aware of the shifting trade-offs as time goes by (as they move up the line), and ready to make decisions on the margin – only taking into account their current position.

Opportunity costs

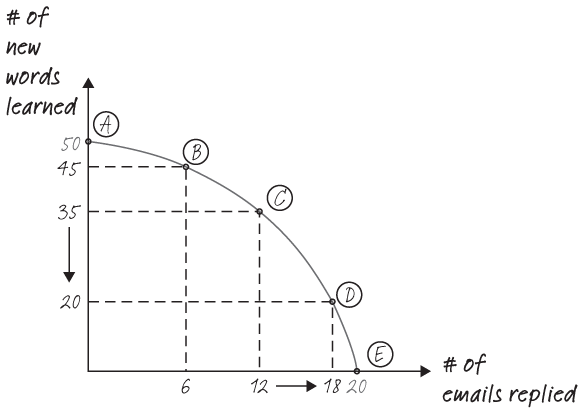

The concept of opportunity costs is closely related to marginal thinking. Let’s say you have one hour available this afternoon to be productive. You could either tidy up your inbox and reply to emails or improve your Spanish. Note that as a function of time invested, both of these activities have decreasing marginal returns just like the yield/fertiliser mentioned. Typing away for a whole hour will make you tired. Holding constant the quality of your replies, the twentieth email will take longer than the first. And for your vocabulary skills, the bottleneck will be your brain’s capacity to process and successfully memorise new terms.

So, for both tasks, email replying and vocabulary memorising, the effectiveness will decline over time. This is exactly why the curve on the previous page is concave. Let’s look at an example. Say you are at point B, which allows you to use the next hour to send 6 emails and learn 45 new words in this hour. And let’s say your holiday to Costa Rica is coming up and you’d like to maximise the number of new words you learn. How many email replies do you have to give up in order to learn 50 words per hour? The cost of learning five more words is six emails. The easiest way to remind yourself about opportunity costs is to ask, “What am I giving up to get this thing? Is that a rational trade?”

Note that the opportunity costs differ based on your starting position. On the margin, if you are at point C, your opportunity costs for one additional word are just 6/10 emails, – half the price than if you were on point A. Marginal thinkers keep opportunity costs in mind (the benefits you would have received had you taken another course of action) to make best use of their time.

CHECKLIST

Marginal thinking

CONSIDER YOUR CURRENT SITUATION

CONSIDER YOUR CURRENT SITUATION

Making decisions on the margin requires you to consider your current situation. Note that it is not important how you got there, but simply where you are. What’s the status of the presentation for your boss? How far along are you in the infrastructure project? Understanding one’s situation and the cost and benefits of action from where you are is crucial for marginal thinking.

LOOK FORWARD

LOOK FORWARD

It doesn’t matter how much money or time you have already put into a project: you can’t go back and change it. Time and money are considered sunk. You should only consider the additional benefit and compare it with the additional cost.

MAP YOUR OPTIONS

MAP YOUR OPTIONS

Going forward, what are your options? Let’s assume you could either put another hour into cleaning your house or start reading the book that’s been lying on your desk for a few weeks. On the margin, reading the book might have a higher benefit to you, assuming your house is already pretty tidy.

DON’T THINK IN BLACK AND WHITE

DON’T THINK IN BLACK AND WHITE

Life decisions are rarely black or white but usually somewhere in between. When deciding what to eat, you don’t ponder between fasting and splurging, but whether to order that extra chocolate mousse after dinner or not.

FURTHER EXAMPLES

Hotel room prices

In the hotel business, operating at maximum capacity is the most important lever to generate revenues. A hotel cannot adjust the number of rooms (these are fixed costs), and the typical expenditures associated with an additional guest (check-in, cleaning, catering) are small compared to the extra revenues gained. Imagine that the extra costs per customer are $50, and the typical price per night is $200. Late at night and off-season, a traveller arrives with only $100 in his pocket. Should the hotel accept the offer? The answer is yes. On the margin, it is profitable for the hotel to do so, even though £100 is somewhat below the regular price per night.

Income taxes

Most governments earn income taxes using a progressive tax system. The tax rate on the additional dollar earned increases with income. For example, in the USA the 2019 tax rate for incomes from $0 to $9,700 was 10%, while the marginal tax rate on earnings over $510,300 was 37%. Using progressive tax systems, countries usually try to curb inequality, because higher-income households have to pay more taxes relative to their income than lower-income households. For freelancers and hourly-paid professionals deciding how many hours to work, it makes sense to think on the margin. They would take home roughly 90 cents per dollar income if the marginal dollar is in the lowest tax bracket, while only 63 cents in the highest tax bracket.

Buying a pair of shoes

Suppose you are looking for a pair of shoes to buy. You really like the ones priced $100 a pair. As you are about to go to the checkout, the shop assistant approaches you and makes you an offer: two pairs for only $150. Although the average price for the pair has now dropped to $75, you should think on the margin. How much pleasure do you actually derive from the second pair? The first pair is clearly worth $100 or more to you, otherwise you wouldn’t have bought them. But is the second pair worth the marginal $50, even though you hadn’t planned to buy them in the first place?

THE BOTTOM LINE

When we make decisions, we often take into account irrelevant factors such as costs incurred in the past. We often fall into the all or nothing trap in which we consider all the benefits and all the costs of a decision situation, which makes decision problems complex and unwieldy. Contrast that with marginal thinking. It requires you to only take into account variables pertinent to your current situation. In its core, marginal thinking is economic thinking, as it always assumes that decisions are made by weighing additional costs against additional benefits. Marginal thinking provides the foundation for rational decision making.