5

Experiencing Technological Change

The previous three chapters have addressed technological change at different levels: social, organizational and individual. They have thus provided insights from different disciplines (anthropology, history, philosophy, economics, psychology) on the subject. This chapter proposes to mobilize these different elements to address the issue of the dynamics of technological change and finally to suggest appropriate practices and change management strategies. To this end, it focuses on supporting technological change within work organizations. This focus allows for a better understanding of the subject and is justified by the fact that much of the technological change comes from and affects organizations, and by the need for managerial decision-makers to have guidelines.

The working organizations also have the particularity of grouping together the three levels described in the previous chapters. Thus, organizations are made up of individuals involved in systems of activities and having to use technical objects (Chapter 4), as well as of collectives of individuals whose dynamics of work and cooperation can be modified by technological change (Chapter 3), and finally they are embedded in a societal ecosystem in which they play a key role (Chapter 2).

This chapter begins by presenting the different threats and opportunities associated with technological change (section 5.1). It thus takes up elements disseminated in the previous chapters, but resituates them at the level of working organizations. It then points out that responding to these threats and seizing these opportunities are linked to the ability to combine social and technological innovations (section 5.2). Finally, it addresses the question of the strategy for managing technological change, and makes some managerial recommendations (section 5.3).

5.1. Threats and opportunities associated with technological change in organizations

The previous chapters have mentioned different types of threats and opportunities associated with technological change. We summarize them here and then study their transposition into working organizations.

5.1.1. Overview of threats and opportunities associated with technological change

Table 5.1 summarizes the threats and opportunities associated with technological change, illustrating them with examples already used in previous chapters and recalling the primary disciplines that have addressed them.

Thus, Chapter 1 discussed, on the one hand, the potential job losses associated with technological change, which may be accompanied by the possibility of automating tasks previously carried out by human beings, and, on the other hand, the construction of a technicist discourse, exaggerating the qualities of technological change and partly masking its negative counterparts. On the other hand, it also mentioned more optimistic discourses on technological change, linking it to social progress in particular. Chapter 2 highlighted several types of threats associated with technological change: technological stress, which corresponds to a malaise linked to the excessive use of new technologies; violence, born of the historically established link between technologies and war; crime, where technology enables criminal actions, as is the case for cybercrime; discrimination, where technology becomes exclusive or discriminating, which is the case, for example, when technologies (automobile, medicine, visual recognition, etc.) do not take sufficient account of the diversity of human characteristics; and finally, ecological degradation, linked among other things to the fact that technological changes are leading to lifestyles that consume more energy resources. But it also suggested cases where a technological change could represent an opportunity, particularly in the service of a more inclusive society, or by providing more environmentally sustainable solutions. Chapter 3 referred both to the threat of a prescriptive and alienating technology, leaving aside people who do not have the necessary skills to master it, and to the opportunity of a technology which assists the human at work and in the implementation of complex projects. Finally, Chapter 4 suggested that technology could be integrated into activity systems, in particular, by facilitating certain activities.

Table 5.1. Overview and characterization of threats and opportunities associated with technological change

| Threat/opportunity | Example | Disciplines | |

| Chapter 1 Threats | Automation and job destruction, unemployment | Automation of production lines | Economics History |

| Technological ideology, lies about technology | Presentation of nuclear power as a highly sophisticated form of energy production | Philosophy Political science | |

| Chapter 1 Opportunities | Social progress | Progress in printing that has contributed to the dissemination of knowledge | History |

| Chapter 2 Threats | Technological stress | Excessive use of ICTs | Psychology |

| War, violence | Technology in the service of war | Economics History | |

| Criminality | Cybercrime | Economics History | |

| Discrimination | Technology designed primarily for certain populations | Sociology | |

| Ecological damage | Automotive, energy consumption, etc. | Ecology Philosophy | |

| Chapter 2 Opportunities | A more inclusive society | Technologies to promote the inclusion of people with disabilities | Sociology |

| Progress in the field of sustainable development | Technologies for recycling or waste reduction | Ecology | |

| Chapter 3 Threats | Prescriptive technology, alienation | Production line, management software packages | Sociology |

| Digital divide | Removal of individuals who do not master new technologies | Psychology Sociology | |

| Chapter 3 Opportunities | Technology to assist in realization and work | Assistance in the production of prototypes and models | Economics Ergonomics Sociology |

| Chapter 4 Opportunities | Technology that facilitates daily and professional life | Remote communication tools | Ergonomics Psychology |

In addition, Table 5.1 also seeks to report on the disciplines that can highlight or shed light on a particular threat. Of course, this categorization does not reflect the great complexity of each subject and the overlap between disciplines. However, it shows that these threats have been addressed by a wide range of human and social science disciplines. Thus, while economics has made it possible to highlight the threats to employment and the links, particularly financial and economic, between war, crime and technology, sociology has been able to highlight the risks of discrimination, alienation and exclusion of individuals according to their command of technology, as well as the contributions of technology to a more inclusive society. Philosophy, for its part, has highlighted the existence of a technicist ideology and the associated risks, particularly in ecological matters. Psychology has focused on the negative effects of technologies on individuals, highlighting the risks of discomfort and stress, as well as the contributions of technology to activity systems. Finally, history is essential to place technological change in a temporal context and to identify threats that may have occurred in the past, and the social progress to which technological and logical change may have contributed.

5.1.2. Threats and opportunities also concerning work organizations

The overview of these threats and opportunities shows their great diversity. It also shows that they cover different levels (societal, organizational, individual). However, it is also possible to transpose them to the level of working organizations (see Table 5.2).

Thus, technicist ideology is relatively common in work organizations, including overconfidence in technology, and the idea that a tool can significantly improve an organization’s efficiency and performance. For example, a company can sometimes implement a tool and build a discourse around the fact that it will lead to efficiency gains, forgetting the difficulties generally associated with this type of transformation (see Box 5.1).

Table 5.2. Transposition of threats to work organizations

| Threat/opportunity | Transposition to work organizations | Example |

| Technological ideology, lies about technology | Discourse exaggerating the merits of a new tool | Implementation of a software package whose qualities have been exaggerated and difficulties hidden: a tool that does not meet a real need |

| Automation and job destruction, unemployment | Dismissals, departure plans, restructuring | Dismissals following the automation of a production line |

| Social progress | Improvement of working conditions and social climate | Dissemination of machines to reduce work accidents |

| War, violence | Competition between companies | Increased competition in areas where technological change is rapid (e.g. digital, telecommunications, etc.) |

| Criminality | Cybercrime | Personal data file retrieved by hackers |

| Discrimination | Discrimination | Recruitment algorithms that discriminate against certain profiles |

| A more inclusive society | More inclusive organization | Work tools enabling people with disabilities to perform the same tasks as non-disabled people |

| Ecological damage | Excessive energy consumption | Data storage centers |

| Progress in the field of sustainable development | More ecological organization | Energy-saving technologies (e.g. automatic light switch-off, etc.) |

| Prescriptive technology, alienation | Prescriptive working technologies | Production line, software package management |

| Technology to assist in realization and work | Technology to assist in realization and work | Software package modeling |

| Technology that facilitates daily and professional life | Technology that facilitates professional life | Tools that facilitate remote working (e.g. e-mails, video conferences, etc.) |

| Digital divide | Removal of individuals who do not master new techniques | Digitization of all work processes, without sufficient training of individuals |

| Technological stress | Stress at work related to ICT | Burn-out |

In addition, automation can lead to redundancies. In other cases, technological change can, on the contrary, be a source of social progress for organizations, for example, when it contributes to improving the social climate or working conditions. For labor organizations, war can take the form of competition between firms, exacerbated by a technological change as illustrated by the digital sector, for example, and cybercrime can result in theft or piracy of data files on customers or workers, whether by internal or external actors (see Box 5.2).

The issue of discrimination is of great importance within work organizations. Indeed, many processes, including recruitment or promotion, can lead to the discrimination and exclusion of certain populations: women, the elderly or young people, non-white people, etc. Technologies can contribute to these discriminations, as is regularly denounced for recruitment algorithms (O’Neil, 2016), but they can also promote the emergence of more inclusive working environments. Companies’ concerns for ecology are reflected in the creation of CSR (corporate social responsibility) functions. However, technological change can contribute to both worsening the ecological balance of organizations, for example through the increasing use of energy-intensive data storage spaces, or on the contrary to improving it, for example through energy-saving technologies. Prescriptive technologies occupy a very important place in the world of work. Thus, assembly lines, or even management software packages, sometimes leave individuals with little margin of autonomy, which raises the question of their alienation. On the other hand, other technologies help individuals in their work and can free them from the most difficult tasks. The digital divide can take the form of the exclusion of people who do not master the technologies, for example, in the case of the implementation of a new digital work tool involving certain skills, through a lack of sufficient training of the people who will use it. Finally, technological stress takes the form of stress associated with the use of new communication tools in work organizations (Brillhart, 2004).

Finally, this table indicates that, for work organizations, the threats and opportunities associated with technological change are numerous. Threats could justify the emergence and maintenance of technophobic discourse, as discussed in Chapter 1, for example, aimed at limiting the role of organizations in technological change. However, as we saw in Chapter 3, organizations play a major role in technological change: they are privileged places first of all for the production of new technologies and then for their dissemination. In addition, technological change is also a source of opportunities. So what solutions can be proposed?

5.2. Reconciling technical and social issues

The effort to reconcile technical and social issues makes it partly possible to respond to the threats and opportunities described in the previous section, in particular, by triggering technological change in response to a social or societal need. Initially more present at the societal level, the notion of social innovation or responsible innovation can also be transposed to organizations.

5.2.1. Social or responsible innovations: definitions and examples

Social innovation is generally defined as a response – not just a technical one – to poorly met social needs, in particular because the State or the market does not take them sufficiently into account. It is very similar to the notion of responsible innovation, i.e. an innovation that takes into account its negative externalities and seeks to limit their effects (Laurent, Baker, Beaudouin and Raulet-Croset, 2018). Social and responsible innovation thus covers a multitude of areas and objectives: the fight against poverty, unemployment, the management of demographic ageing and sustainable development, for example. Two perspectives can be proposed to define and study social innovation (Klein, Laville and Moulaert, 2014). Thus, the philanthropic perspective focuses on initiatives that aim to improve people’s living conditions, while the democratic perspective focuses on innovation as a factor of democratization of society. In both cases, social innovation is characterized by a specific process and ecosystem.

5.2.1.1. The social innovation process

Social innovation arises first of all from an unmet social need. The first step is therefore to transform a collective need into a social need, i.e. to make it a cause that goes beyond the strict collective of the individuals concerned. Thus, the struggles against unemployment, poverty, poor housing and global warming are now considered to concern all societies (see Box 5.3).

The second step is to propose a solution to meet this need. This solution generally combines a technical dimension with a social or societal dimension (see Table 5.3).

Table 5.3. The technical and social dimensions of social innovation

| Technical dimension ➜ social dimension | Web platform/IT solution | Object/tool | Know-how |

| Sustainable consumption | Platforms for the sale of second-hand clothing | Fairphone: smartphone whose parts can be replaced separately | Workshops for repairing objects (e.g. bicycles) |

| Recycling | Recycling trash cans near farms | Workshops for refurbishing and reselling cell phones | |

| Charity | Platform for reselling concert tickets for the benefit of charities | Isothermal shelters for the homeless | Insertion structure specialized in the collection and reuse of electronic and office equipment |

| Volunteer work | Platforms for connecting volunteers |

This table gives several examples (not exhaustive of course) of a combination between a technical dimension (here: a platform, an object, know-how) and a social dimension (here: sustainable consumption, recycling, charity, volunteering). Thus, Internet platforms can be used to promote sustainable consumption through the sale and purchase of secondhand clothing, as well as through charity, with the resale of tickets with donations to charitable associations, or through voluntary work, with the establishment of links between volunteers and associations. As for technical objects or tools, the table mentions “Fairphones”, smartphones designed with separately renewable parts, which increase the lifetime of the device (see Box 5.4), or sophisticated recycling trash cans, as well as isothermal shelters for the homeless, designed to conserve heat and therefore provide (certainly temporary) shelter solutions in the event of extreme cold. Finally, the last column is devoted to know-how in the repair and refurbishment of objects, which is part of both sustainable consumption and recycling objectives. These skills can also be a means of integration for unemployed people.

Finally, social innovation aims to address an unmet social need by combining a social dimension of changing practices with a technical dimension (e.g. digital platform, specialized know-how). It can be described as responsible insofar as it seeks to meet major societal challenges and aims at a form of ethics.

5.2.1.2. The actors of social or responsible innovation

Another characteristic of social or responsible innovation is that it involves many actors, sometimes not used to cooperating together: companies, government actors, research institutions, non-market organizations (Klein, Laville and Moulaert, 2014). Thus, the social innovation ecosystem can be divided into several categories of actors: designers, funders, supporters and users.

The designers of social innovations can have different statuses: associations, NGOs, companies, start-ups, individuals or groups of individuals, etc. Some innovations can be directly associated with the names of individuals, such as École 42 founded by Xavier Niel in France (see Box 5.5), while the affiliation of other initiatives is much more difficult to establish, as in the case of free software and code (see Box 5.6).

Financers of social innovations can take many different forms:

- – solidarity-based finance (investment funds specializing in the social and solidarity economy, for example);

- – corporate foundations;

- – crowdfunding platforms;

- – public funders (States, local authorities, public institutions, etc.);

- – classic banks.

These different actors are not mutually exclusive, as the same social innovation project can benefit from several funding sources.

Actors who support social innovations can contribute in different ways. Thus, some actors aim to provide information and guidance to project leaders, while others aim to provide development and management assistance (incubators, professional networks, etc.).

Finally, the users of social innovations are also extremely diverse (individuals, associations, etc.).

Among these different actors, the role of States is both highlighted and questioned in the literature on social innovation (Laville, 2014). Indeed, by aiming to meet a social or collective need, social or responsible innovations sometimes take over from public authorities in certain fields traditionally covered by them (e.g. the fight against poverty, the fight against illiteracy).

However, they do not necessarily reflect a disengagement of the State, which can support the shareholders of social innovations through financing or aid policies. Moreover, ensuring the conditions for the emergence of social innovations in sovereign domains could be an important quality of a truly democratic state (Laville, 2014).

5.2.1.3. Responsible technological innovation, a response to the criticisms and threats associated with technological change?

Finally, social innovations seem to respond to the main threats identified in the first section, while at the same time allowing the main opportunities to be seized. In particular, they make it possible to meet certain societal challenges (recalled, for example, in Chapter 2) and seek to respect a form of ethics. In the field of technological change, we take this into account by calling them responsible technological innovations (see Table 5.4).

Table 5.4. Responsible technological innovation, a response to the threats and risks associated with technological change

| Threat/opportunity | Social or responsible innovation | Examples of responsible technological innovations |

| Technological ideology, lies about technology | Social innovation aims to meet social needs, not create technologies that are of no real use | Organizations promoting the sustainable development and professional integration of local populations (e.g. Aki Energy in Canada) |

| Automation and job destruction, unemployment | A part of social innovation is at the service of the integration and employment of unemployed people | Refurbishing workshops employing people who have been unemployed for a long time (e.g. Ateliers du Bocage d’Emmaüs in France) |

| Social progress | Social innovation aims to meet social needs and is at the service of improving living and working conditions | Technological innovations that contribute to the improvement of working conditions for certain individuals (e.g. exoskeletons for carrying heavy loads) |

| War, violence | Social innovation aims to meet social needs, including peace and healing | Technological innovations aimed at reducing the consequences of wars (e.g. humanitarian drones to deliver food or drugs, or to map territories) |

| Criminality | Social innovation aims to meet social needs, including reducing crime | Technological innovations aimed at reducing crime or combating the effects of crime (e.g. emergency telephones for victims of domestic abuse) |

| Discrimination versus a more inclusive society | Most social innovations serve a more inclusive society by addressing social needs not covered by dominant institutions | Technological innovations to improve access to entertainment, careers or services for certain populations (e. g. prostheses to allow individuals with lower limb disabilities to run) |

| Ecological degradation versus sustainable development | A whole range of social innovation is at the service of sustainable development | Technological innovations aimed at sustainable development (e.g. Fairphones in the Netherlands) |

| Prescriptive technology, alienation versus technology which facilitates professional activity | Social innovation puts people at the center of its development | Technological innovations that contribute to the empowerment of individuals (e.g. Solidarity Clouds for homeless people such as Reconnect in France) |

| Digital divide | Tackling the digital divide can be the subject of social innovations | Training networks for digital professions for unemployed people (e.g. Simplon.co) |

| Technological stress | Social innovation aims to meet needs and therefore does not create unnecessary technologies; information and communication technologies, in particular, are used to serve human beings (and not the other way around). In addition, combating technological stress can be the subject of social innovations | Solidarity Cloud services allowing homeless people to keep documents (e g. identity documents) in digital form (e.g. Reconnect in France) |

Thus, responsible technological innovation is applied to several areas that respond to many of these criticisms, in particular: the integration of unemployed people, which is to be compared with the risk of automation and job destruction, and sustainable development, to be compared with ecological risk. Moreover, responsible technological innovation aims to meet a social need and, in this respect, it responds to the risk of a technicist ideology disconnected from reality and the risk of war and violence. Thus, some innovations seek to reduce crime or the effects of war on individuals. Secondly, social or responsible innovation arises when a social or collective need is not covered by dominant institutions and therefore often benefits dominated populations, which explains its links with the social and solidarity economy (Laville, 2014). In this way, it partly responds to the risk of discrimination related to technological change. Finally, one of its characteristics is to put the human being at the center and to promote the social and human dimension over the purely technical dimension, which responds to the risk of prescriptive technology and the alienation of the human being through technology. Many responsible technological innovations also meet the objective of empowering individuals, which contradicts the image of an alienating and prescriptive technology. Fighting the digital divide is another area in which responsible technological innovations are multiplying, such as Simplon.co, a start-up that targets the most vulnerable populations.

5.2.2. Responsible technological innovations within organizations

As this chapter is primarily devoted to technological change within organizations, particularly work organizations, it is now time to focus on the transposition of responsible technological innovations within organizations. Organizations thus maintain multiple links with responsible technological innovation: they are places of production, as well as of diffusion of these innovations.

5.2.2.1. Organizations as places of production for responsible technological innovations

Many responsible innovations are the result of organized collectives of individuals: companies, associations, cooperatives, unions, NGOs, etc. The social and solidarity economy sector thus includes many of these organizations (see Box 5.7).

The links between responsible innovation and the social and solidarity economy are particularly strong. Thus, the voluntary sector has historically been a laboratory for responsible innovation, particularly in the technological field, since associations have had to find solutions to social needs not covered by public authorities or companies (in the fields of housing, health, ecology, etc.).

In addition, commercial companies can also offer responsible technological innovations. The Fairphone company already mentioned is an illustration of this. The challenge is therefore to identify the conditions for the emergence and production of these responsible technological innovations within market organizations. Based on the definition of social or responsible innovation, they seem to us to be as follows:

- – to identify an unfulfilled social need, sometimes not put on the agenda by public authorities;

- – to reason outside established structures and concepts;

- – to put the issue of economic and financial profit on the back burner;

- – to link the social and technical dimensions.

Thus, as we have seen, the first step is to identify an unfulfilled social need, sometimes not even put on the public agenda. However, if the need is not put on the public agenda, it means that, to identify it, it is necessary to reason outside established structures and institutions. Moreover, if the need is put on the public agenda but is not met, it probably implies that it is difficult to satisfy this need in established structures and institutions. In this second case too, reasoning outside established structures, institutions and concepts seem necessary. Secondly, as we have seen in the social and solidarity economy sector, social innovation is also characterized by putting the search for profit on the back burner (Oosterlynck and Moulaert, 2014). Finally, it is necessary to link the social and technical dimensions, as social innovation is based on the interweaving of the two (see Table 5.3).

5.2.2.2. Responsible technological innovation, a vector for democratizing organizations?

As mentioned above, a whole field of research is concerned with social innovation as a vehicle for democratizing society (Klein, Laville and Moulaert, 2014). Therefore, the transposition of this perspective to work organizations could imply that some social innovations related to technological change could make work organizations more democratic. Two elements and examples seem to us to support this point.

First of all, a dialogue with employee representatives, an essential element of corporate democracy, can in some cases allow forms of social innovation linked to technological change. Oosterlynck and Moulaert (2014) thus give the example of a dialogue with social partners on the dissemination of new information technologies (see Box 5.8).

Secondly, social innovation in some cases implies the active participation of workers in its production, and this is just as true in the case of responsible technological innovations. Organizational learning theory thus reflects a movement to integrate knowledge from work practice into organizational processes. It is therefore a vertical upward movement, which ensures that innovation responds to a need and consists of both a technical and a social dimension. Thus, an operator can innovate by developing new work tools or technologies, which can eventually be integrated into work procedures, and which other operators, in turn, will have to use or apply. This theory is thus based on the premise that workers are best able to develop innovations that meet their own work needs. Similarly, in the case of technological innovation to meet societal needs, it is sometimes workers who have had to deal with difficult situations who propose to their organization an innovation to meet these types of situations. Such participation may, in some cases, take the form of intrapreneurship, already mentioned in Chapter 3, when employees develop social innovations within their own companies (see Box 5.9).

Finally, social or responsible innovation is a form of change that combines a technological dimension with a social and societal dimension. In this way, it responds to some of the criticisms made by some researchers in the human and social sciences against technology. The development of responsible technological innovations requires the participation of different groups of stakeholders, including work organizations (e.g. companies), as producers and beneficiaries of these innovations. Indeed, the latter can contribute to organizational democracy through the development of dialogue and participation of employees and their representatives.

5.3. Managing responsible technological change

This last section aims to build on the elements given in the previous sections to propose suggestions for improving the management of technological change. Indeed, while the literature on the management of organizational change is particularly abundant, we propose a change management model that takes into account the specificities of technological change and aims at a responsible technological change.

5.3.1. Organizational change management

The literature on the conduct of organizational change is particularly abundant. It makes it possible to identify key dimensions for characterizing a change and the associated change management strategy (Barel and Frémeaux, 2009).

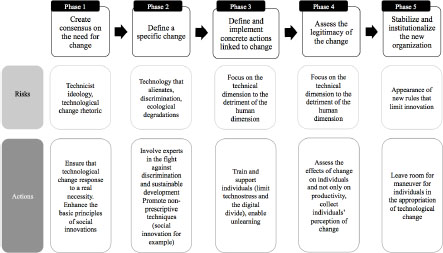

5.3.1.1. A prescriptive model for change management

Among other things, researchers have proposed prescriptive change management models. Thus, Philips (1983) starts from the observation that there are three key factors for successful organizational change: the quality of the new strategic vision, the development and dissemination of the skills required for this strategic vision and organizational support (leaders, managerial line, etc.). He thus derives a four-phase planned change management model (see Figure 5.1). A first step is to build consensus within the organization on the need for change. This can be done, for example, by offering training on socio-economic change, by leaders speaking out or by setting up small groups of influencers convinced of the need for change and responsible for disseminating this conviction to those around them. The second phase aims to launch a movement of commitment towards a specific change: the definition of the strategic vision and of the resulting organizational vision in particular. The third phase consists of defining and implementing actions to enable change: training if new skills are needed, changes in operating and working methods or job creation or reduction, for example. Finally, the fourth phase should make it possible to consolidate the new organization, for example by institutionalizing the new rules.

Figure 5.1. Example of a change model

(source: adapted from Philips, 1983)

5.3.1.2. Contingency factors for change management

However, this type of prescriptive model overlooks the fact that a change management strategy is contextual, in the sense that it also depends strongly on the type of change involved (Pettigrew, 1987; Weick and Quinn, 1999) and that there are alternatives to planned change. There are many types of organizational changes. Table 5.5 represents a non-exhaustive attempt at an overview that provides examples of dimensions that structure organizational change.

The first dimension concerns the extent of the change and its reversibility. Some changes, such as a change in managerial culture or a massive reorientation of the organization’s activity, affect several departments and lead to in-depth organizational renewal. Conversely, other changes are less important: reorganization of a team, marginal modification of a work process. The extent of the change then determines the strategy to be adopted. Van de Ven and Poole (1995) thus distinguish situations of change that concern a single entity of the organization (a department, a site, for example), and situations that concern several or all entities. In France, the example of the social crisis of the late 2000s at France Télécom illustrates a change strategy that is not adapted to the scale of the targeted changes (see Box 5.10).

Table 5.5. The structuring dimensions of change and associated strategies

| Dimension | Examples | Authors |

| Scale of change | Global change, involving changes in several parts or departments of the organization, or local change, corresponding to experiments with new operating modes in small areas, before possible generalization | Van de Ven and Poole (1995) |

| Employee participation in change | Top-down approach, imposing change through the hierarchical channel, or bottom-up approach, favoring the emergence of innovations from the field | Philips (1983); Barel and Frémeaux (2009) |

| Steps in the process | Technical change (tools, machines, etc.) before social change (learning, culture, discourse about change, etc.) or vice versa | Philips (1983); Pettigrew (1987) |

| Source of the change | Market needs, increased competition, employee proposals, etc. | Van de Ven and Poole (1995) |

| Rate of change | Rapid or long-term change | Weick and Quinn (1999) |

| Change frequency | Organization/sector accustomed to permanent changes, or on the contrary to a certain stability: continuous or episodic change | Mintzberg (1979); Weick and Quinn (1999) |

| Characteristics of the organization | Age, size, status, organizational model, cultural inertia | Mintzberg (1979); Weick and Quinn (1999) |

The second structuring dimension concerns the place given to individuals in change. Thus, some changes are decreed by the company’s management (see Box 5.10) and imposed on individuals without their participation: this is therefore a prescribed change (Van de Ven and Poole, 1995). On the other hand, some organizations seek to involve employees in change, through working groups or collective workshops to bring forward proposals. However, it is still necessary to distinguish between situations where the results of these collective reflections are really taken into account to define the facets of change, and those where employee participation is only illusory, in the sense that it does not influence the path of change (see Box 5.11).

The third dimension refers to a distinction between situations where change is thought of as primarily technical, and those where it is thought of as primarily human. Indeed, as we have pointed out, while, change is often both technical and human, organizations tend to strongly separate the two dimensions. Thus, a company that decides to change its main working tool can promote the “tool” vision, focusing on technical aspects, and, for example, on the operational and technical prerequisites for the implementation of the tool, or on the contrary a “human” vision, focusing on individuals and highlighting, for example, the need for training and individual and collective support. Moreover, this primacy given either to the tool or to the human can influence all stages of the process (see Figure 5.2).

Figure 5.2. Promoting the technical or human dimension when changing work tools

Thus, when choosing the tool, the company may focus on technical considerations (technical specifications, functionalities, version changes envisaged, for example), or be more interested in what the tool will change for individuals, in terms of autonomy, skills implemented or daily activities. Then, when the tool is installed, the technical dimension focuses on compliance with the technical specifications or interfacing with the other tools. On the other hand, organizations that focus on the human dimension will pay attention to the challenges of training and coaching individuals, and will seek to listen to them in order to better understand the obstacles to tool implementation. Finally, tool assessment may also depend on the preferred dimension. Thus, indicators related to the productivity or use of the tool (functionalities used, number of bugs in the tool, for example) can be mobilized, or on the contrary indicators referring to people’s perception and experience with the tool or their well-being and autonomy.

The fourth dimension refers to the factor that triggers change: the need to adapt to market developments, economic problems, as well as changes in management teams, employee proposals, etc. Van de Ven and Poole (1995) thus make the “generating force” of change a differentiating factor between four ideals of organizational change, and identify four types of generating force: institutional or regulatory changes, competition and the market, internal organizational conflicts, and the collective and consensual definition of new objectives. Indeed, the triggering factor of change strongly influences the discourse held on the necessity and legitimacy of change, which constitutes a key element of the change management strategy, as we have seen (Philips, 1983). Box 5.12 thus returns to the rhetoric of the need for change in work organizations.

The pace and frequency of change (dimensions 5 and 6) are important and interrelated dimensions. Thus, some organizations, because of the sector in which they operate as well as intrinsic characteristics, have a culture of permanent and rapid change. Weick and Quinn (1999) refer to this type of change as “continuous change”. In contrast, other organizations are characterized by a change that is described as “episodic”, less frequent and with a shorter time frame. Weick and Quinn then suggest that two paradigms of change should be distinguished. The first, described as “Lewinian”, is based on the following assumptions: organizational inertia, linearity of changes and developments, progressive development and the pursuit of objectives. In this model, change results from an imbalance or external intervention that makes the original organization obsolete. Conversely, the second model, described as “Confucian”, is based on the following assumptions: cyclical and permanent organizational movement, permanent change and no organizational inertia. Thus, the first model seems more suitable for studying and leading episodic changes, and the second for continuous changes.

Finally, the characteristics of the organization constitute a dimension that strongly structures change (dimension 7). Thus, Mintzberg (1979) identified “contingency factors” affecting the structure of organizations and the distribution of power within organizations: age, size, sector of activity, etc. However, the structure and distribution of power, in turn, affect how change is approached (see Box 5.13).

The wide variety of situations linked to change therefore makes it difficult to formulate a single prescriptive model linked to a change management strategy. Moreover, a model such as the one proposed by Philips (1983) does not specify the content of phase 3 (“defining and implementing concrete actions related to change”), which seems to constitute the crucial phase of a change management strategy.

5.3.2. The specificities of technological change

To clarify the content of this phase 3 in the case of technological change, it is first necessary to highlight the specificities of this type of change.

5.3.2.1. Managing unlearning and skills acquisition

We have listed the conditions for the emergence and production of technological innovations that respect individuals within organizations. The ability (collective and individual) to unlearn seems to be a common denominator under these different conditions. However, this requires that organizations manage their skills in a way that respects these cycles of unlearning and innovation.

The literature on organizational innovation highlights the importance of moving beyond pre-existing rules and procedures for the development of innovation (Alter, 2000). This is all the more important in the field of responsible technological innovation, which also challenges the usual codes of innovation. However, this “unlearning” contrasts with the current logic in work organizations. Drawing on Schumpeter’s work and the expression “creative destruction”, Alter (2000) shows how much innovation and adoption of innovation require breaking free from socially established rules. This is all the more true in the business world, where there are two contradictory injunctions represented by the need for innovation and renewal and the need to respect codes, rules and procedures. He thus gives examples where an innovation that was rationally interesting could not be deployed in organizations. Beyond the world of work, there are many examples of technological innovations whose deployment is contrary to established habits and rules (see Box 5.14).

These examples illustrate a phenomenon known as path dependence (Arthur, 1989). Arthur points out that in the field of the adoption of new technologies, yields are increasing, in the sense that the more a technology is adopted, the more significant its use is, therefore the more improvements it will benefit and the more other technologies will be added to it, which will reinforce the adoption of the first. He then examines the adoption of competing technologies and shows that, in many cases, the technology that ultimately wins the competition for adoption is not necessarily the most “effective”, but has benefited from sometimes minor circumstances that led to its adoption first, and has quickly become a dominant or even monopolistic technology. In addition to the example of the Dvorak keyboard mentioned in Box 5.14, he illustrates his point with the example of nuclear power generation in the United States. Nuclear energy can be produced with light water, heavy water, as well as gas or sodium. However, in the United States, the nuclear industry is largely dominated by light water reactors, a choice that dates back to the first nuclear submarine (1954), while gas-fired reactors seem rationally more suitable.

Path dependence is also present in work organizations, for at least two reasons. First of all, working requires relying on a number of tools, know-how and “ways of doing things”, which are all habits that are difficult to change. Thus, introducing a tool into an organization that requires changes in processes or work habits is always tricky and sometimes doomed to fail (see Box 5.15).

Secondly, as Alter (2000) points out, work organizations are based on a set of rules and processes that are difficult to challenge, which hinders innovation capacities. According to this sociologist, who partly takes up Schumpeter’s (1999 (1926)) work on the subject, the “entrepreneur”, i.e. the individual who wishes to propose an innovation in an organization, cannot be part of the rationalist aim of management, since he does not have previous experience or data enabling him to legitimize the interest of his innovation. In addition, the entrepreneur also faces individuals whose activity may be modified, or even threatened, by innovation. Therefore, it is in the entrepreneur’s interest to comply with the organization’s injunctions in the first instance, or even to conceal the potential effects of their innovation, until the latter’s interest is recognized within the organization. The entrepreneur is therefore always at some point in a situation of deviating from the organization’s rules: they must go beyond these rules, overcome them and probably sometimes unlearn them to be able to carry out their project successfully.

While innovation requires some form of unlearning, this seems even more true for responsible technological innovations. Indeed, these innovations require a double renewal, technical and societal, as we have seen. In the previous section, we listed the conditions for the emergence of social innovations: reasoning outside established structures and concepts; putting the issue of economic and financial profit in the background; and linking the social dimension to the technical dimension. However, these conditions require unlearning ways of working that are deeply rooted in most work organizations. Indeed, the question of economic and financial profit remains most of the time the main issue for profit organizations. Moreover, as the previous chapters have shown, the decoupling of technology and social issues remains common, and success in linking the two therefore requires an unlearning of this decoupling. Finally, responsible technological innovations are also characterized by the networking of a number of actors not used to cooperating, for example large multinationals with local workers, or multinationals with associations. This once again requires a review of pre-established patterns of cooperation between the different institutions. The intrapreneurs mentioned in Box 5.9 have therefore had to insist in some cases in order to convince their organization to set up new partnerships with these unusual actors.

However, unlearning is not necessarily seen as legitimate within work organizations, which are based on the rhetoric of building up skills rather than practices that challenge existing ones (Kuhn and Moulin, 2013). In fact, many factors can hinder “organizational unlearning” (Tsang and Zahra, 2008; Kuhn and Moulin, 2013):

- – the organization’s length of existence;

- – training seen only in terms of adaptation to the workplace;

- – very settled work routines;

- – rigid processes and rules.

Thus, it is sometimes difficult, if not impossible, for organizations to promote the unlearning of rules, routines and skills.

5.3.2.2. What kind of skills management?

However, unlearning is not enough: as Chapter 4 has pointed out, it is also necessary to be able to acquire and appropriate new skills (including knowledge, know-how and meta-knowledge; see Aubret, Gilbert and Pigeyre, 2005). Indeed, technological change is often accompanied by the emergence of new skills necessary to produce technological innovation as well as to seize it. Thus, as Chapter 4 noted, digitalization has gone hand in hand with the emergence of skills linked, for example, to communication on social networks or the use of digital tools. In addition, recent decades have seen an acceleration of change, leading to more uncertain predictions of the skills needed for work organizations. It then becomes necessary to disseminate interdisciplinary skills which are useful whatever the development of the organization (Aubret, Gilbert and Pigeyre, 2005). Two HR processes are particularly relevant: recruitment and training (Cadiz and Pointet, 2002).

Recruitment allows individuals with new skills to enter the organization. It is particularly suitable in situations where a skill is difficult to develop internally. For example, nowadays, organizations are trying to recruit data scientist profiles, knowing that data expertise requires a significant amount of training time and high expertise, which makes it difficult to develop these skills internally.

The link between recruitment and technological change is twofold: an organization may want to recruit people who can propose innovations, or people who have mastered new techniques to capture innovations. In the first case, recruitment involves an assessment of a person’s potential for innovation. This can be a particularly difficult exercise because the potential for innovation is not measured against the most traditional recruitment criteria (diploma, professional experience, etc.). This may then require organizations to renew their recruitment process and criteria. This explains the development of new recruitment tools, such as the escape game or the video CV, which allow candidates to distinguish themselves with atypical skills. Moreover, recruiting a person with high innovation potential is limited if the new recruit must then comply with the organization’s codes and requirements, which can, on the contrary, hinder the spirit of innovation (Alter, 2000). In the second case, recruitment requires the assessment of expertise, which is done, for example, through the diploma criterion. However, this criterion loses its relevance with the development of self-study movements, particularly in the field of computer science (many self-taught people learn code or new computer languages by their own means). As a result, other recruitment practices are developing, such as hackathons, which allow candidates to be assessed in real IT development situations (see Box 5.16).

Work organizations may also choose to develop and disseminate skills internally. This then involves training aimed at developing the innovation potential of individuals or enabling them to appropriate new technologies without having to resort to external recruitment. Three training models stand out in particular: a vertical top-down diffusion model of skills (from top to bottom, through company training, for example), a vertical bottom-up diffusion model (from bottom to top, through reverse mentoring, in particular) and a horizontal diffusion model (by peers).

Some companies set up ambitious and costly training plans, sometimes based on internal trainers, particularly in large companies. This training can be useful in disseminating work rules and procedures. In the case of technological change, such training can be mobilized to support change, for example, in the case of the implementation of a new work tool (Aladwani, 2001). Training then becomes a means of encouraging employees to use the new tool (see Box 5.17).

On the other hand, training of this type does not seem to be well suited to developing the innovative potential of individuals. More recently, companies have experienced a development in reverse mentoring, which characterizes situations where individuals are led to train people who are higher up in the hierarchy or have more years of experience. This system is particularly well suited to the dissemination of skills considered new (e.g. related to new digital technologies), or to the development of the organization’s innovation potential. Indeed, the younger generations are considered to master these new skills more easily and to have a higher potential for innovation because of their new view of the organization than the older generations (see Box 5.18).

Finally, some topics and work environments are more suitable for the horizontal dissemination of knowledge through a system of peer-to-peer exchanges. This peer-to-peer diffusion experienced several transformations between the 20th and 21st Centuries, from communities of practice to networks of ambassadors and networks of collective competence (Alter, 2000). Communities of practice, like companionship, are made up of groups of individuals who work together or on the same subject, and are thus led to find together and share among themselves solutions to practical and concrete problems in their daily work. Networks of ambassadors are made up of employees who, on a given subject, will be identified as being able to help or train their colleagues (see Box 5.19).

Finally, innovation in work organizations requires a form of unlearning, all the more so when this innovation goes against the usual reference frameworks (pursuit of profit, efficiency, myth of technical rationality, etc.), as is the case for social innovation. However, this unlearning must go hand in hand with skills management to develop and disseminate the skills required to innovate and keep pace with technological change.

5.3.2.3. Strategies for managing technological change

To conclude this book, we mobilize the contributions of the previous sections to address the question of the management of responsible technological change and thus provide some recommendations in this area.

The contributions of the previous sections allow us to identify the specificities of technological change and how change management can take them into account (see Table 5.6).

Table 5.6. The specificities of technological change

| Dimensions | Sub-dimensions | Change management |

| Threat management and seizing opportunities inherent to technological change (section 5.1) | Automation and job destruction, unemployment | Supporting the employees affected |

| Social progress | Studying from the outset the effects of technological change on individuals and the social climate | |

| Technostress | Implementing anti-stress measures (stress related to technological change) | |

| Discrimination versus more inclusive organization | Involving anti-discrimination experts in the early stages of change processes | |

| Ecological degradation versus sustainable development | Involving sustainable development experts upstream of change processes | |

| Prescriptive technology, alienation versus implementation assistance technology | Promoting technologies that meet real needs and leave room for maneuver to individuals | |

| Digital divide | Training all employees in new technologies | |

| Employee participation in innovation or its diffusion (section 5.2) | Responsible technological innovation | Integrating the principles of social or responsible innovation: responding to a need, including a technical and social dimension, putting the human being at the center |

| Employees who propose innovations | Making the organization’s rules and codes more flexible in order to preserve the innovation potential of individuals | |

| Unlearning (section 5.3) | Need to unlearn old technologies or ways of doing things in order to be able to innovate and appropriate new ones | Accepting the disappearance of certain skills |

| Technical skills management (section 5.3) | Recruitment | Recruiting people with innovation potential or mastering new technologies |

| Training | Training employees in new techniques or developing their innovation potential: top-down training, reverse mentoring, communities of practice or networks of ambassadors |

Thus, the first dimension concerns the management of risks related to technological change identified in the first section of this chapter. The challenge for work organizations is to limit these risks or the effects of these risks on individuals. This involves, in particular, efforts to support employees, for example, by redeploying employees whose jobs may be lost, or by training employees to ensure that they have the necessary skills to cope with this change. The example of digital ambassadors mentioned above (see Box 5.19) illustrates how a company can try to ensure a good diffusion of digital skills. This also requires upstream reflection on the consequences of technological change for individuals and the social climate, and raising the awareness of the various actors on certain subjects: stress at work, discrimination and ecological degradation in particular. With regard to stress at work, it may be appropriate to put in place stress measures specifically related to technological change. In addition, involving expert actors in the fight against discrimination and sustainable development (internally, the diversity department or the CSR department, for example, as well as external consultants if necessary) from the outset of the change project can help to limit the risk of discrimination and ecological degradation. Finally, the risk of alienating individuals by technology can be avoided or reduced by taking into account the criterion of the room for maneuver left to individuals when choosing technologies and making changes.

The second dimension concerns the participation of workers in the production and diffusion of innovation. This point, discussed in the second section of this chapter, is divided into two sub-dimensions. Firstly, we discussed the notion of social or responsible innovation, and how this notion partly responds to the risks inherent in technological change. Therefore, one way for organizations to ensure responsible technological change is to integrate into the change process the principles of responsible innovation: to verify that technological change responds to a real need, that it has a human dimension and not only a technological dimension, or that the change process puts people at the center. This refers to Figure 5.2 and the distinction between a process that focuses on technical aspects and one that focuses on human aspects. Then, in connection with the notion of social innovation, we stressed the need for employee participation in change. We also pointed out (in the third section of this chapter) that, while organizations regularly issue injunctions for change and innovation, internal codes and procedures often stifle creativity. Therefore, ensuring employee participation in change may require flexibility in these rules, codes and procedures.

The third dimension concerns the notion of unlearning. In the third section, we pointed out that unlearning (of ways of working, as well as of codes and conventions) is an essential condition for technological change, but that organizations often see unlearning as a failure. Accepting the disappearance of certain skills seems to be both a difficulty and an important issue for organizations.

The fourth dimension concerns the management of technical skills. The management of technological change influences key processes such as recruitment and training. In the context of recruitment, it is a matter for organizations to recruit people with a potential for innovation or mastering new technologies. In both cases, this requires a reflection on the recruitment process and the mechanisms used to select applications: exercises to assess potential or the command of a rare technological skill. We have thus given the example of hackathons for assessing mastery of the most advanced computer skills (see Box 5.16). On the training side, in the same way, organizations can have two objectives: to develop the innovative potential of individuals, or to train them in new technologies. Once again, this may require mobilizing original training mechanisms differently from top-down company training: reverse mentoring, networks of ambassadors, etc.

5.3.3. An integrative scheme for the management of responsible technological change

Finally, the management of technological change, while taking up certain dimensions of change management in general, has specific features that should be kept in mind when setting up a strategy in this area. In this last section, we propose to combine the contributions of the two previous sections to propose an integrative model of responsible technological change management. We thus use Philips’ (1983) model, presented in Figure 5.1, adapting it to take into account the various elements mentioned above, and, in particular, to recall the risks inherent in technological change and the actions that organizations can take to limit them (see Figure 5.3).

Figure 5.3. Leading responsible technological change

(source: adapted from Philips, 1983)

Thus, in the case of technological change, the first phase, which corresponds to the construction of a consensus on the need for change, presents a risk (linked to the technicist ideology) of illusions about the validity of technologies and therefore of technological change. At this stage, the actions to be taken to limit this risk are aimed at ensuring that this change meets a real need and fully understanding the potential negative effects of the technology. Mobilizing the principles of social innovation can be a solution at this stage (technological change must meet a need, have a technical and social dimension, put people at the center).

The second phase refers to the definition of a specific technological change. This phase presents several risks related to the technology in question: this technology may be alienating, discriminatory or contribute to ecological degradation. In addition to ensuring that the technology meets a real need, involving experts in the fight against discrimination and sustainable development in the choice of technology can help to limit these risks.

The third phase corresponds to the definition of the actions necessary to support technological change. The main risk in this phase is to focus on the technical dimension rather than the human dimension (see Figure 5.2). To limit this risk, it is advantageous to carry out actions focused on individuals at work: training and support. Moreover, enabling unlearning seems appropriate to promote the acquisition of the skills necessary to appropriate a new technology.

The fourth phase, which we have added to Philips’ original model, is aimed at evaluating technological change. This assessment may be limited to technical aspects (productivity gains or the number of bugs in the tool, for example). Conversely, assessing a technological change that is more respectful of individuals and more sustainable may also involve assessing the effects of change on individuals (technostress, well-being at work) and individuals’ perceptions of change.

Finally, the fifth phase refers to the institutionalization of the new organization or the new technology. This institutionalization involves, among other things, the formalization of new rules, new procedures and new ways of working linked to the new technology. The main risk then lies in excessive formalism and in the definition of rules and procedures, leaving little room to maneuver for individuals, which again highlights the notion of alienating technology. To limit this risk, organizations must ensure that they maintain flexibility in the appropriation of technology.

- 1 www.economie.gouv.fr/entreprises/structures-economie-sociale-et-solidaire-ess, accessed on November 2019.