Chapter 5

Patterns of a Strategically Effective CIO

This chapter provides evidence of why certain chief information officers (CIOs) have attained success as a strategic driver of their businesses. This evidence is presented from the case studies from Chapter 4 and integrates our findings based on our theories of why certain CIOs are more successful than others. As stated earlier, these results have led us to understand the patterns that suggest why certain CIOs obtain success in introducing IT strategy to their firms and how they build credibility among C-level peers in their organizations.

We concluded Chapter 4 with presenting 24 key attributes of successful CIOs. These skills were divided into two categories: (1) personal attributes and (2) organizational philosophy. We expand each of these attributes further here to include more theory and practical guidance.

Personal Attributes

We defined personal attributes in Chapter 4 as “individual traits that appear to be keys for IT leadership.” The following section provides an expanded description of these 11 attributes as they relate to the value it brings to the business.

1. Push Yourself Outside Your Professional Comfort Zone

Successful CIOs need to keep reinventing themselves and should strive for continual excellence at their jobs. Look for more responsibilities in different places outside the normal IT functions.

Much has been written about what makes certain individuals want to progress to higher stages of maturity. Kegan, in his book In Over Our Heads, described learning as being able to go beyond one's comfort zone.1 He described the willingness to evolve as being directly correlated to a “value proposition.” In other words, individuals learn because they have a reason to, an objective, to move to another level of sophistication. Kegan also recognized that transformation has its rewards but also losses—these losses are those that one gives up by moving to the next level. The loss can be what successful CIOs have called “the reinvention of themselves.” When people reinvent themselves, they must be willing to move outside their comfort zone—a zone that they have previously mastered. So it requires an individual to have a certain drive to want to succeed at the next level, to give up their comfort for the rewards of that next level. The CIOs who achieve that success are the individuals who have now broadened their responsibilities in tangential areas of responsibilities, like operations and shared services. Indeed, business strategists have long realized that the ability of an executive to learn faster or “better” than his or her competitors may indeed be the key to long-term business success.2

Langer's case study, “Fixing Bad Habits,” showed that the use of reflective practices was key to supporting individual learning and subsequent transformation.3 Furthermore, this study found that such development greatly enhanced the adaption of new technologies, the understanding of strategic value, and the improved assimilation into the social norms of the business.

There is clearly a positive correlation of CIO development to theories of individual growth. This suggests that CIOs need to evolve their roles by developing a mindset that supports adapting new ideas, thinking processes, and the ultimate willingness to change. Those CIOs who continually defend old norms likely will be unsuccessful as change agents, which is what CEOs define as a critical attribute in today's technology leaders.

2. Communication Skills Are at the Forefront of Leadership

Without great communication skills CIOs cannot influence the business or even imagine an integration strategy.

Social discourse and the use of language are critical to creating and sustaining internal interactions. Technology dynamism and responsive organizational dynamism (ROD) show that the context of globalized forces have added to the complexity of understanding “the language and symbolic media we employ to describe, represent, interpret, and theorize what we take to be facticity or organizational life.”4 Langer translated this into the need to develop a “language of technology.”5 That is, how do we incorporate technology into the normal processes of discourse—how can we make technology an “organized discourse” so that it can be integrated into the day-to-day speak of the business?

The importance of great communication skills, then, in accordance with our interviews, suggests that success lies with the CIO's ability to make the social connections with his/her colleagues and staff. These connections require CIOs to use many different forms of communication including language, talk, stories, and conversations, all of which represent the heart of social life. These types of communication require learning because it involves sense-making and builds on the knowledge development of the organization. This becomes critical for CIOs to implement ROD, especially in dealing with change driven by technological innovations. Indeed, Dana Deasy stated in our interview that telling stories was a huge part of his strategy throughout his career. Simply put, those CIOs who understand the process of how technological concepts need to be delivered are those who will have more success at the C-suite.

The concept of converting learning to strategic benefit was pioneered by Willie Pieterson.6 He established a learning cycle that can be used to transition learning concepts into better communication approaches. He created a strategic learning cycle that comprised component processes that contained four action verbs: learn, focus, align, and execute. The explanation of each is as follows:

CIOs can use Pieterson's learning model as a template for preparing conversations with business partners. The Execute step, in particular, has significant relevance in communication success, specifically, its implication that interpretation is a cycle that requires multiple loops. Here, we translate this into the cycle of communication, where one idea could require multiple loops of communication until the community of participants reach agreement. It is important to note that the CIO is part of this community and thus may need to adjust and negotiate during the cycle of communication.

3. Do Not Become Too Enamored with Politics

CIOs should not overplay the power of playing politics. Successful CIOs tend to be direct with their colleagues and staff.

We do not suggest that politics is not an active part of organization life, rather that it is important to distinguish between what is good politics and bad politics. Good politics can be defined as the normal interactions of how things get done in organizations. It is often mistaken for bad politics, which are the destructive agendas and actions taken by people against others for unethical gain. The feedback we received from the interviews, particularly those made by Koster from Prudential, distinguishes the salient differences between the two and how often individuals misinterpret what is really strategic advocacy rather than bad politics.

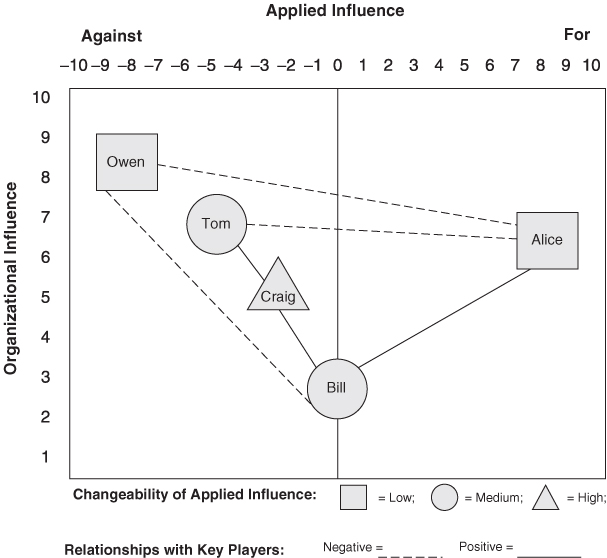

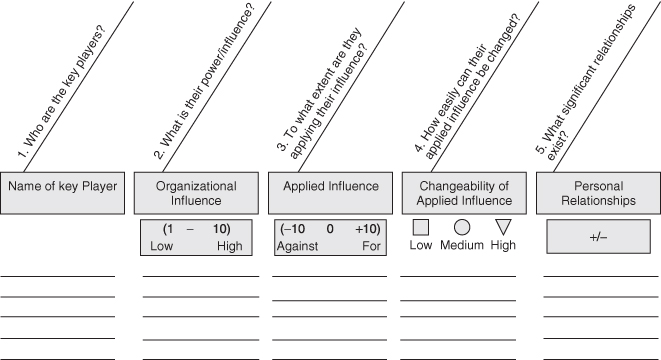

Deluca provides five basic questions for mapping the political territory for purposes of strategic advocacy:

Deluca defines these advocacies as political savvy, which he describes as the “unofficial influence approaches occurring out of sight in most organizations.”8 As Deluca states:

Political savvy entrepreneurs will know how to better cut across organizational, cultural, and geographical lines to put together strategic alliances. Not only among individuals within the organization, but across multiple businesses as well.9

It is interesting that Deluca refers to entrepreneurs in this context. Indeed, we believe that CIOs need to perceive themselves and operate with an entrepreneurial mindset. Notwithstanding the cultural norms of whether strategic advocacy is cast as good politics in many organizations, Deluca provides a way of using politics in a positive way. Figure 5.1 provides a data sheet that can be used to determine the relative strengths of political relationships in the organization. This “political mapping” can be used to develop a strategic plan to influencing key players in the organization.

Figure 5.1 Organizational Mapping Grid

Source: J. Deluca, Political Savvy: Systematic Approaches to Leadership Behind-the-Scenes (Berwyn, PA: EBG, 1999).

Using the grid, then, CIOs can develop the strategic goals using Figure 5.2.

Figure 5.2 Political Mapping Goals

Source: J. DeLuca, Political Savvy: Systematic Approaches to Leadership Behind-the-Scenes (Berywn, PA: EBG, 1999).

Perhaps the most effective way to distinguish good politics from bad politics is the questions of ethics. Those who transform good politics into strategic advocacy using Deluca's approach do so by choosing to become an active and ethical participant as opposed to a destructive force for personal gain at all costs.

4. Do Not Shy Away from Tough Decisions

CIOs must do what is necessary, especially with their staffs and constituents. If someone is not performing, do the right thing and make the necessary changes.

Having the ability to make tough decisions is an attribute of any good leader, certainly not limited to the role of a CIO. However, we find that many short tenure CIOs are not very good managers. The topic of tough decision making is a subset of a larger subject often referred to as tough-minded management. Batten defined a tough-minded manager as one who would be impatient with the “unused potential” of the people working for him or her.10 The essence of tough management is to develop the talent, to push your people to their maximum strengths and to see the value of the organization as the sum of all the strengths of each individual. So the goal for a CIO is to develop those strengths in each person. Batten offers a number of general guidelines:

- Individuals tend to be happier when they are pushed, stretched at work, and pulled into many different areas of responsibility.

- Managers need to develop a person's weakness as an underdeveloped strength—so it's like using a negative as a potential positive.

- Always expect high performance. Do not allow mediocrity in your staff.

- Care enough about individual strengths to emphasis it as part of all assessments of performance and organizational successes.

Ferrell and Gardiner provide seven distinct attributes of tough-minded managers:

Inferred in tough-minded managers are high degrees of ethical behavior. Thus, setting an example and working as hard as those around you are significant aspects of achieving excellence. The CIOs in our cases not only get the performance from their staffs, but also receive their admiration—they set an example, stretch themselves as much as they do their staffs, and always work on building their strengths.

The more difficult challenge for CIOs is dealing with those who either continually underperform or do not buy into the “sum of the parts” which ultimately defines the value of the whole. Indeed, Langer's study of Ravell showed that employees are not always authentic and some individuals will engage in political behavior that can be detrimental to any organizational learning effort.12 Simply put, they are not interested in participating. In such cases, leaders must make the tough choice to eliminate such people from the organization. Thus, as much as a CIO should attempt to find the right place for an individual to contribute, acceptance of continual poor performance or a lack of enthusiasm for the objectives of the organization by any employee is detrimental to the success of the IT department.

5. Get Used to Ambiguity

If you need to be told exactly the problem, you will likely not bring much value. The life of most executives requires an existence in the uncertain and poorly defined.

Many of the students in our Executive IT Master's program at Columbia University are challenged with coursework that requires them to deal with ambiguous problems. They tend to ask us, “Can you tell me exactly what you want?” These students often have well over 10 years' experience and are at senior management positions. Yet they have lived in IT environments that are very requirements specific—learning that they need to understand the specifications in order to proceed. Furthermore, IT specialists tend to be developed in a learning environment that is scientific, which advocates the need for specifics and clarity. However, executive responsibilities are often vague, cloudy, and require creative methods of helping others understand what they really need. In fact, the higher you get, the more vague things are—typically goals are clear, like we need to cut the budget, we need to increase margin. However, such goals come without the specifics of how to attain them—that's where CIOs need to improvise and figure out how to get to the end point of what is needed. We always tell our students that those dealing with ambiguity are at the forefront for getting compensated well! Indeed, why do we require executives who need to be told what to do all the time?

Eichinger and Lombardo developed a model of dealing with ambiguity which is used as a Microsoft learning training tool. They define three essential “expert” qualities:

They suggest using the following self-questions to help assess these skills:

- What decision must I make to minimize risk in spite of not having all the information?

- What new project can I undertake today, even though I have other things in the works?

- How can I prepare others right now for the impact of an anticipated change?

- What disjointed task or project can I organize?

- Is there someone with whom I must “clear the air” or make amends?

- What big task can I break down into smaller tasks to facilitate its completion?

Their research also provides additional suggestions for “overcompensating for ambiguity” or as they define “overdoing ambiguity”:

- May move to conclusions without enough data.

- May fill in gaps by adding things that aren't there.

- May frustrate others by not getting specific enough.

- May undervalue orderly problem solving.

- May reject precedent and history.

- May err toward the new and risky at the expense of proven solutions.

- May overcomplicate things.

Unfortunately, there is much literature that trains managers how not to be ambiguous with their staffs! It is interesting that the way we develop managers tends to prepare them poorly for life at the C-suite.

6. Take Risks

A strategic CIO cannot achieve success without engaging in projects that have risk factors—it's reality. The challenge for the CIO is to understand the extent of the challenge and the significance of the rewards to the business.

The conversation surrounding risk taking is quite complex. Risks almost certainly support a level of failure—failure, as we discussed earlier, is not generally accepted for IT initiatives. But IT risk and failure rate must become part of the reality for many firms. Langer defined this risk with driver projects—calling for the creation of a “batting average” defining this as the rate of failure for a new IT initiative.

It became apparent to us, especially during our interview with Passerini from Proctor & Gamble, that failures are essential components of achieving success. To always operate in an environment with low risk likely provides for little upward mobility, and likely will underprepare a young CIO for success at the C-suite. We learned that how one deals with the failures can be very advantageous because those at the C-suite have all experienced a “run rate.” Indeed, most failures that are within the risk rate—or rate of failure, are not really failures!

However, this concept does not suggest that CIOs should feel free to fail. The point is that they must establish the rate of failure for Driver projects within an acceptable rate. This rate must be consistent with the firm's acceptable ROI. We already defined that failure rates are not acceptable for supporter projects.

A supporting factor for establishing an IT batting average is to use benchmarks. Unfortunately, many CIOs use benchmarks from other IT projects, which in many cases is problematic because the C-suite executives are more interested in industry data that can foster competitive advantage. Therefore, it is more impressive to use industry data from operational or sales sources. For example, use sales risk factors in the industry and correlate them to risks of IT projects given that shifts in market needs will often change IT requirements.

Dana Deasy, when he was CIO of the Americas for Siemens Corporation, dealt with the challenge of establishing the viability of IT risks. The challenge at Siemens was how technologies could be tested to determine exactly how it might impact the business. In order to address this dilemma, Deasy established the concept of “revalidation.” Specifically, approved technology projects were reviewed every 90 days to determine whether they were indeed providing the planned outcomes, whether new outcomes needed to be established, or whether the technology was no longer useful. This required that IT be given the ability to invest and experiment with technology in order to fully maximize the evaluation of IT in Strategic Integration. This was particularly useful to Deasy, who needed to evolve the culture at Siemens to recognize that not all approved technologies succeed, as well as to dramatically alter the expected life cycle of how software applications were evaluated by IT and senior management. This challenge was significant in that it had to be accepted by over 25 autonomous presidents, who were more focused on shorter and more precise outcomes from technology investments.

Deasy was able to address the challenges that many presidents had in understanding IT “jargon” specifically as it related to the benefits of using technology. He engaged in an initiative to communicate with non-IT executives by using a process called “storyboarding.” Storyboarding is the process of creating prototypes that allow users to actually see an example of how the technology will look and operate. Storyboarding tells a story and can quickly educate executives without being intimidating. Deasy's process of revaluation has its own unique life cycle at Siemens:

- Create excitement through animation. What would Siemens be like if…

- Evaluate how the technology would be supported.

- Recognize implementation considerations about how the technology as a business driver is consistent with what the organization is doing and experiencing.

- Technology is reviewed every 90 days after experimental use with customers and presented to the C-suite on an “as-needed” basis.

- Establish ROD, that is, the reality of instability of technology and that there are no guarantees to planned outcomes, rather promote business units to understand the concept of “forever prototyping.”

7. Lead without Authority

Great leaders can influence the behaviors in others without using the power of their position. Influencing the change of behavior in others is far more sustainable.

There has been much written about what represents leadership. There are many definitions, but most agree that true leadership starts with the ability to influence the behaviors of others without the use of power. As managers rise to executive levels of management, their power among their colleagues actually decreases—many have opinions at the C-suite, and anyone can be questioned. This is unlike the rise to management, which is typically based on individual performance rewards. Those individual performances are rewarded with promotions that require more responsibility. With more responsibility, one typically receives the power to lead. Such is no longer the case at the C-suite where influence becomes the more relevant factor for success.

Conger, a professor at London Business School, suggests that executives must use more lateral styles of leadership.14 His article in Harvard Management Update titled, “Exerting Influence without Authority,” states that lateral leadership provides a “constellation of capabilities.” The constellation comprises four intertwined capabilities:

While lateral leadership makes sense it is difficult to train managers to exercise it. The problem stems from those executives who might seek advice and support from other colleagues and then do not receive it. However, there is no question that the successful CIOs have mastered the practice. Their success, we believe, can be attributed to high levels of individual perseverance and passion. Remember, “No only means no now!”15

8. The Importance of Technical Skills Diminishes as You Approach the CIO Position

CIOs should not confuse IT knowledge with skills. Skills relate to doing; knowledge better supports management of others.

Still today, most CIOs come from IT technical backgrounds. It is very difficult to let go of one's reliance on their technical expertise, which has served to catapult their careers. However, the importance of technical skills becomes less important as one climbs the ladder into the C-suite. Actually, the technical experience is assumed at the C-suite, but not used in discourse. Indeed, being too technical might work against an executive manager, who might be seen as unable to transition to the broader management challenges of their area of responsibility.

At the CIO level, human skills and conceptual skills become more important. The human skills involve a manager's ability to work with people and in particular motivate others. Ultimately, the human factor helps executives establish effective teams that can get things done. Conceptual skills can be related to the abilities presented in the later stages of Langer's CIO Arc. It allows CIOs to think abstractly and thus provides the ability for them to formulate long-term plans, policies, and overall business direction. One's technical expertise is still important however—as it provides the basis to build human and conceptual actions.

CIOs must always remember that many see them as techs and geeks and must be very sensitive to stay away from using technical jargon at business meetings. Unfortunately, we have seen time and time again that IT people tend to gravitate back to technical terms, especially when they are under stress. It takes practice to lose that reliance, but those who are successful have mastered the balance and the slogan: “Talk business above and technical below!”

9. Have Pride of Ownership

There is no better judge of excellence than your own. CIOs need to strive to be the best and take responsibility for their actions.

Those who are successful at what they do love their jobs and take great pride in what they do. Our successful CIOs are no different and want very much to leave something behind in the organizations they manage. Part of striving for the best is having someone to look up to. All of our case study subjects discussed people who made a difference in their professional lives and influenced certain of their behavior patterns. This does raise the question of whether a manager has had the opportunity to be mentored or developed by a senior person during their professional development. A number of CIOs we have met have hired coaches to personally assist them in developing what they see as weaknesses.

CIOs who have pride of ownership are great models for their staffs as well. They are the executives who others strive to be like, and motivate their people simply by displaying the dedication to excellence that they expect from themselves. It has been proven that most employees want to excel at their jobs, but less and less staff, particularly middle managers, receive the necessary attention they require to develop further. Current CIOs should be cognizant of this trend and attempt to provide formal and informal structures to help develop the next generation. Indeed, Sarbanes-Oxley requires that CIOs have the appropriate personnel to replace key positions in their IT organization. Furthermore, those CIOs who have been promoted into more senior operations positions have typically selected and nurtured their replacement before moving on.

10. Learn to Listen

CIOs must learn to listen to the feedback they receive and listen to what people really need. Too many CIOs think they know what people want, which often is not accurate.

We are continually amazed how well leaders listen. They listen to issues, what their staffs are saying to them, and especially listen to their customers. Most important, they must listen to what their superiors and peers are saying. Too often, we have seen failed CIOs who tell us that they simply had no idea they were in trouble. The signs of dissatisfaction, upon review by these CIOs, typically reveal that messages were sent to them, but because they did not reflect on what was really being said, they missed the opportunity to address their shortfalls.

Research has shown that only 25 percent of people listen efficiently even though most feel they listen extremely well to their staff and supervisors. Effective listening executives need to help their people to solve important problems but must first truly understand the problem. How often we hear that peers complain that the CIO does not understand the issues. Likely, it's because the CIO is not listening to them in detail.

Ultimately, great executive listeners better match their responses to the situation at hand. They also reflect more on what is being said and have the ability to “reflect-on-action,” which is the process of thinking about what has occurred and what might be effective actions to change the situation. At the CIO level, these reflections often require a change in behavior—that is, the actions and processes that a CIO uses to deal with interactions.

11. Do Not Accept Mediocrity

We live in a competitive world and expecting the very best from your staff is critical, especially from a global perspective.

Thomas L. Friedman and Michael Mandelbaum's book, That Used to Be Us, discusses the problems with accepting mediocrity.16 Simply put, they state that global competition has made mediocrity unacceptable. Those executives who are mediocre will likely disappear. The concept of seeking excellence is not just an individual desire, but one who effects the entire organization. Thus, CEOs and boards expect the best from the least. The notion of rejecting mediocrity can be aligned with Prahalad and Krishnan's notion of N = 1 and R = G discussed in Chapter 1.17 With consumers in control of what they want and when they want it, resources must provide the very best support and deliver products and services on demand. Thus, organizations today regularly examine global resources to meet those consumer demands in a just-in-time (JIT) delivery manner. As a result, the process of where to hire people, the percent of outsourced resources at lower prices you use, and where to get the best services, is an ongoing challenge to remain competitive in a global economy.

The result of the consumerization substantially fostered by IT innovations will continue to challenge CIOs to think broader and to constantly investigate new ways of providing JIT products and services. However, providing the resources is no longer enough; the services must be the best or someone else will take the business away from you. CIOs must therefore be JIT in thinking; they must react quickly and have global resources around the world that can provide answers—answers that provide actions to respond to new market needs.

Organization Philosophy

We defined organization philosophy in Chapter 4 as issues that represent the way the organization should operate. The following sections are an expansion of each of the 12 critical issues cited in our CIO interviews.

1. Integration of IT Is a Fundamental Objective

Successful CIOs understand that integration means that IT resources are truly embedded in the business. This requires CIOs to move their resources and ensure that they spend time with their colleagues in the business.

As stated earlier, Schein was the first scholar to see the IT and non-IT personnel collision between what he called “two cultures.”18 That collision must now be resolved and full integration must prevail. The question is how best to do that. Obviously, the CIO, being the most senior executive in IT, must lead the way to figuring out the best way to accomplish full integration. Using Einstein's ongoing quest to find a unified theory to deal with quantum physics, CIOs too need to find a unified method to complete IT and business integration.

Langer offered first steps to providing a concrete way of completing a unified integration by dividing IT into two groups: drivers and supporters. The supporters would remain as separate entities, with drivers being absorbed into their respective business units. A unified integration, however, requires both sides to become active. CEOs can no longer sit in the background and hope that their executive team will figure it out. There must be an agenda of unification and a decision to how best to migrate resources for optimized performance throughout the businesses.

Some CIOs might see unification with the business as an approach that could lead to their becoming “disenfranchised,” worrying that they will ultimately lose their value to the business. Warren Kudman, CIO of Sealed Air, offers interesting insights to this dilemma. While he agrees that CIOs need to work closely with their business units and maintain great flexibility, Kudman's IT organization is centralized and decentralized—so he provides maximum flexibility to provide many of those strategic driver needs that the business requires to survive, but at the same time centralizes those supporters. As Kudman stated, “I am in a model where IT is very centralized but my team is decentralized globally.” Kudman brings up an important point: Do we just give away the resources or attempt to provide maximum flexibility with “just enough governance to maintain control while avoiding a lot of non-value-added bureaucracy and overhead?”

Ultimately, Kudman feels that the business must make the decisions and IT needs to be there to provide the guidance and best operating practices. He fears that business units that manage IT people directly may not have the appropriate career perspectives for IT staff—so it can be a dead-end move for IT professionals. There certainly is justification in these concerns. However, “just making an organization shift may not solve the real problem,” as he puts it.

Perhaps there is middle ground to this dilemma. We discussed the notion of allowing IT personnel to “move” to a business unit, but not permanently. This might provide the best of both worlds—true integration without hurting long-term career growth. Such a strategy is not new. Japanese firms actually would assign their business managers to work in IT organizations to better understand their strategic potential. Why not do this with IT personnel in reverse? Our critique though still remains: Controlling IT budgets across the business can be problematic, so while your IT resources are operating inside a business unit, why not let them be responsible for the cost? Passerini found actually spending the time in the business invaluable. He transformed his operation by establishing the “service manager” position in an effort to create true unification. Ultimately, we believe that true integration can only be accomplished by taking more drastic measures. Indeed, history has shown that almost all CIOs agree with integration but few have accomplished it.

2. CIOs Must Be Knowledgeable about the Business

This somewhat relates to (1), but also suggests that spending time and integrating resources is not enough. IT must be intimately familiar with the challenges of the business, the way the units operate and their culture. Only with this knowledge can IT become an equal partner.

Another portion of integration is the knowledge challenge. Spending time is one thing, and it certainly improves knowledge transfer, but it does not provide the immediate value that is required today in businesses. Furthermore, how do we educate businesspeople to have them better understand the needs of IT—so that their expectations are more in line with the realities of how innovations mature? So many CIOs at conferences complain that their CEO and C-suite colleagues simply don't get it—failing to ever understand how technology works and why it costs so much and takes so long.

Education is always an option. Sending IT and non-IT people to training programs will provide some leverage for integration, but frankly, it takes too long, costs too much, and often does not embellish the realities of what is occurring in practice. More IT organizations need to embrace the concept of communities of practice, a way of integrating staff who have common goals and expected outcomes in business units.

Communities of practice are based on the assumption that learning starts with engagement in social practice and that this practice is the fundamental construct by which individuals learn.19 Communities of practice are formed to get things done by using a shared way of pursuing interest. For individuals this means that learning is a way of engaging in, and contributing to, the practices of their communities. For specific communities, on the other hand, it means that learning is a way of refining its distinctive practices and ensuring new generations of members. For entire organizations it means that learning is an issue of sustaining interconnected communities of practice, which define what an organization knows and contributes to the business. The notion of communities of practice supports the idea that learning is an “inevitable part of participating in social life and practice.”20 Communities of practice also includes assisting members of the community, with the particular focus on improving their skills. This is also known as “situated learning.” Thus, communities of practice is very much a social learning theory as opposed to one that is based solely on the individual. Communities of practice has been called learning-in-working where learning is an inevitable part of working together in a social setting. Much of this concept implies that learning in some form or other will occur and that it is accomplished within a framework of social participation, not solely or simply in the individual mind. In a world that is changing significantly due to technological innovations, we should recognize the need for organizations, communities, and individuals to embrace the complexities of being interconnected at an accelerated pace.

Furthermore, communities-of-practice theory justifies its use in ROD. Indeed, the size and complexity of technology innovations requires a community focus, which can be mapped to a business unit. This would be especially useful within the confines of specific departments that are in need of understanding how to deal with technological dynamism. Specifically, this means that through the infrastructure of a community, individuals can determine how they will operate with emerging technologies, what education they will need, and what potential strategic integration they will need to prepare for changes brought on by technology. Action in this context can be viewed as a continuous process much in the same way that Langer presented technology as an ongoing accelerating variable. The important thing to recognize here is the business unit becomes intimately involved with goal attainment and that IT personnel must be legitimately part of the community. Education occurs both formally and informally to then help create new identities of the unit and ultimately an evolving culture.

3. Have a Road Map

CIOs need to develop a plan of what they want to accomplish, why it is valuable to the business, and how they will accomplish the objectives. This includes the specifics of cost, ROI, and time to completion.

Having objectives is the first part of any plan. But providing the mechanics of how one will execute that plan and determining the costs associated with any product realization is the major challenge. CIOs do not have a great track record. The IT industry as a whole has not improved its conversion effectiveness. Late projects are the cause for most project overruns. We believe that telling stories, as suggested by Dana Deasy is one very effective way of getting executive support. Deasy used storyboarding as a vehicle to articulate what the technology could do for the business.

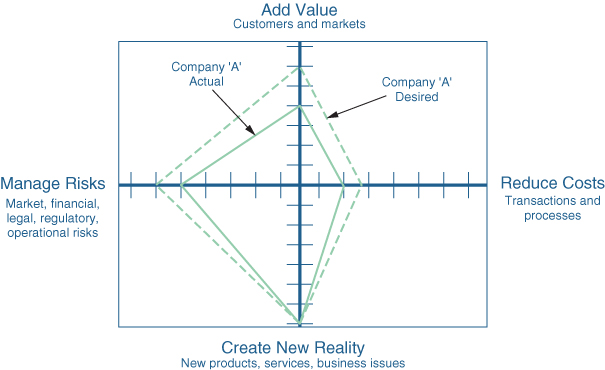

Perhaps an effective framework for assisting CIOs to articulate their strategic plans is Marchand's Strategic Information Alignment (SIA). This framework asks three vital questions that can lead CIOs to know the relevance of their plans to business alignment:

SIA has four major components that determine the focus of any business strategy:

The model examines the relative importance of each of these components. Figure 5.3 is a graphical representation that depicts the relative consistency between IT and company objectives.

Figure 5.3 Strategy Information Alignment Framework

Source: D. A. Marchand, Competing with Information: A Manager's Guide to Creating Business Value with Information Content (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2000).

The solid line reflects where IT operates across the four sectors as compared to the dotted line, which is where the company wants to operate. Using SIA, CIOs can reconcile their IT efforts and understand where they stand. It also provides a graphical tool to represent why an IT initiative, if supported, will better align with the desired business objectives of the firm.

4. Keep Your Pulse on Costs

CIOs still need to be fiscally responsible and must shed the reputation as big spenders. Where IT can be used to reduce costs and increase shareholder value is still an extremely important part of the role.

As they say, all evaluations of projects ultimately lead to an understanding of its costs. Because of the history of overruns it is important that CIOs establish themselves as cost conscious partners with their C-suite colleagues. The biggest challenge, however, is explaining why some costs cannot be easily associated with returns from the IT investment itself. We already noted the nonmonetary valuations theory advocated by Lucas's work, where he established ways of articulating the value of indirect or hybrid benefits of IT investments.21 We still advocate that Langer's driver-supporter model is at the center of addressing this dilemma. Specifically, if all driver IT activities are directly incorporated in the business unit, including staff, then the explanation of the value of any such investment is clearer and more succinct because all the costs are associated with the business effort. This simply leaves the supporter side, which then becomes the center of how to use IT to reduce costs by using outsourcing alternatives, and/or by increasing business unit margins through efficiency.

The most important part of being cost conscious is to behave cost conscious. That is, to represent at meetings that all IT investments must correspond to business value and that the IT organization forever seeks to reduce its Supporter expenses in line with the competition. CIOs must make it part of their repertoire of communications and this alone will help diminish what can be false generalizations about IT as not being cost conscious.

5. Having a Seat at the Table Does Matter

The argument that it does not matter where the CIO actually reports is bogus. CIOs need to report directly to the CEO and have a regular place of attendance at key board meetings. Perceptions are realities, and if the CIO function does not get the top reporting line, then the message to the firm from the top is clear: IT is not important enough.

The ongoing debate on where a CIO reports is serious. We find that where one reports really does matter and advocate that the CIO position should report to the CEO. Under some circumstances where all C-suite positions report up through a chief operating officer (COO), it can be reasonable for the CIO to report that way as well. However, this kind of reporting structure is often relevant in only very large organizations, and even in those cases there are exceptions. For example, it is not unusual for the chief legal counsel or even HR executive to report directly to the CEO. In most cases, the chief financial officer (CFO) will also have a direct reporting line to the CEO unless the COO is actually a former CFO.

The question for the CIO is how to influence that reporting structure. In our case interviews, almost half the subjects did not report to the CEO, yet they were successful CIOs. However, all of them did have direct access to the CEO. The reality is that a direct report to the CEO is likely something that needs to be negotiated prior to starting the job, unless, as in Passerini's and Koster's case you are promoted into the position from within the organization. The most effective assistance for CIOs reporting to the CEO is probably through a third-party advocacy—something like a professional body like the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA), who can issue standards on reporting structure or support certain policies that affect the CIO role. For example, CFOs must sign the financial statements—this places the CFO at a very important position not only with the CEO but also with the board. We believe the most important advocacy is simply the value the CIO brings, and our research supports the notion that the more the CIO positively affects strategic goals, the more likely the CEO would want them as a direct report.

6. Business Comes First

The CIO must always think about the value IT brings to the business. If that business value is not there, then the value of the IT is not relevant.

This concept is certainly consistent with the rest of our support for how IT can bring value to the business. The uniqueness of this issue, in this context, goes beyond just understanding or supporting what the business knows and wants. It opens the door for the CIO to drive business opportunities from a technology perspective. An example of this is what Passerini did to reduce costs of focus groups while improving penetration to the consumer. Another example involves the innovations used by the banks to allow consumers to make direct deposits by taking a picture of a person's check. These examples show how IT can lead the way, certainly not the majority of the time, but the opportunities are there if, and only if, the CIO understands the business and has the creative ability to abstractly see where IT can make a difference.

7. Expand the Role beyond Traditional IT

We saw from our cases that many successful CIOs are now taking on expanded roles outside of just IT issues. This includes operations, infrastructure, and shared services.

The ultimate reward for contemporary CIOs is their advancement beyond the role itself. We have seen this occur in many industries and in special cases. Indeed, Passerinni has risen to the level of a group president; Koster on the executive management team at Prudential, and Scalet taking on related operating responsibilities for shared services and real estate. Banks have also promoted its top CIO to the role of chief of operations and technology. Given that technology can affect many aspects of the business, there is increasing opportunity to evolve and reinvent the position.

History has shown us that CIOs who fail to expand their roles may very well endanger their longevity on the job. The formidable threat usually occurs when someone else takes the responsibility away from you, that is, another peer will take the initiative of providing services that require IT. Should this occur it conveys a negative message to your peer executives that you may lack the necessary business skills to evolve the CIO position.

One of the potential career paths for CIOs is to take on a more chief administrative officer (CAO) role. This position would include the overall traditional CIO functions, but also include operations, certainly not in the same context of the COO, but a position that expands the use of technology into all operational areas in a firm. The advent of the CIO as an operating executive is certainly under way in many industries, as previously noted. We expect to see this continue to grow in consideration among CEOs because it allows the CIOs to improve automation benefits throughout the firm.

8. Have the Best People

CIOs cannot accomplish their complex roles without surrounding themselves with the appropriate staff. In actuality having the best IT staff is extremely important to securing an effective supporter function.

It is becoming increasingly important for the CIO profession to start thinking about the next generation of talented CIO leaders. That responsibility lies with our existing leaders—leaders who need to prepare for the education and development of their most talented staff.

Yet we do not see enough of such investments. Corporations have continued to cut their education budgets, and new CIOs cannot learn their jobs from experience alone. As faculty who manage a CIO leadership program, we see little increase in applications for master's degrees in technology management. Further, there is a lack of diversity in the application pool, especially with women. Thus, not enough future stars are investing in their education and may be “ill-prepared” for the challenges that lay before them. Far more concerning is the lack of interest in becoming a CIO. There are too many negative discussions that occur at CIO conferences—if CIOs are not excited about the role then few will venture to take it on.

Simply put, our CIO leaders need to accelerate the search for their successors. They need to create a pool of potential future stars, that requires future CIOs to have field experience with the businesses and an education program that broadens their knowledge beyond what current managers are experiencing at their jobs.

The following are some of the issues to consider:

- Rotational programs. Put star managers in six-month roles in the business units. This allows them to become much more knowledgeable about the business. More important it gives them exposure, so they become known across the business.

- Education. Continuing education and conferences are fine, but allow IT managers to enroll in a part-time degree program where they get exposed to a broader education and get to meet other executives. A committed degree program also establishes a more critical and reflective person and one who can think in the abstract, beyond just the concrete needs of the business today.

- Diversity. This issue is of paramount importance to our future generations. Diversity goes beyond the legal and corporate requirements. The world is flat, as they say, and having a pool of diverse candidates provides a company with broader knowledge and better decisions—so promote more women and more ethnicity in your organization.

- Up and out. Do not worry about losing those who you invest in. It happens and should happen. Great companies develop talent and lose some of them—indeed, there are only so many positions at the top. If you provide the program, those who leave will always remember it and some will return. Remember, talent development is a responsibility as much as an investment. Finally, it will add to the prestige of your company—that you invest in your people.

- College graduates are not the only entry-level candidates. In fact, they may not be the best solution, given the costs. We have seen great success in creating a competitive workforce using high school graduates who complete technical certifications and complete their college degrees part time. Germany has had amazing results with apprentice programs to fill certain skill jobs, and they have set an example to fill needed talent.

Not all of the resources will be employees. Selecting the right outsource providers are equally important. The CIO must be careful with the outsource firm's they select, especially since many of them suffer from high turnover. However, balancing employees with outsource talent is a reality, and CIOs need to have strategic relationships to accomplish R = G! Furthermore, good firms always compete on talent—just like Microsoft and Google tend to seek the same talent, so too must the CIO in their related industry.

9. Pay Attention to Big Data

Data analytics, as discussed earlier, has become an increasingly important conversation at the board level. Big Data is essential for competitive advantage and also understanding a firm's legal exposures and security coverage.

Data analytics is the quickest growing area of concern at the board level. Understanding what data tells us and how it adds to knowledge are critical needs for global organizations, especially those that deal directly with consumers. Big data is somewhat a subset of a larger topic called knowledge management—the ability of a firm to manage its data and maximize its utilization for competitive advantage as well as protection of its assets.

This increasing recognition that the competitive advantage of organizations depends on its “ability to create, transfer, utilize, and protect difficult-to-intimate knowledge assets” has given birth to the value of Big Data.22 Indeed, according to Bertels and Savage, the dominant logic of the industrial era imposes the challenges of understanding how to break the learning barrier of understanding the information era.23 While we have developed powerful solutions to change internal processes and organizational structures, most organizations have failed to address the cultural dimensions of the information era. Organizational knowledge creation is a result of organizational learning through strategic processes. Nonaka defines organizational knowledge as “the capability of a company as a whole to create new knowledge, disseminate it throughout the organization, and embody it in products, services, and systems.”24 Nonaka used the steps shown in Figure 5.4 to assess the value and chain of events surrounding the valuation of organizational knowledge. This organizational knowledge feeds Big Data needs, which ultimately provide an understanding of the data both inside and outside the firm.

Figure 5.4 Assessing Organizational Knowledge

Source: I. Nonaka and H. Takeuchi, The Knowledge-Creating Company: How Japanese Companies Create the Dynamics of Innovation (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995).

According to Nonaka, to create new knowledge means to recreate the company and everyone in it in an ongoing process that requires personal and organizational self-renewal. That is to say, knowledge creation is the responsibility of everyone in the organization. The viability of this definition, however, must be questioned. Can organizations create personnel that will adhere to such parameters, and under what conditions will senior management support such an endeavor? Once again, the CIO has a remarkable role to play in substantiating the need for knowledge management, Big Data, and the competitive advantage it brings to the firm.

10. Align with the Business

This somewhat relates to (2). But it is not enough to be knowledgeable. The CIO must be aligned with the aspirations of the business units so that there is interdepartment harmony.

There is much written about the importance of relationship building. So many CIOs miss this and pay dearly for the lack of having an integrated relationship strategy. At the heart of relationship building is bringing value—but not from your perspective; rather, the perspective of the “other.” The question to ask is: who are the others?

Well, the first “other” is the “C-level” colleagues, including the CEO, of course. As previously stated, a relationship with C-level colleagues goes beyond a meeting, even a drink, it's really about understanding their needs and what brings value to them. This is accomplished through formal and informal meetings and discussions.

Formal meetings are ones that should be initiated by you and typically allow the CIO to assess how IT can bring value—it also allows CIOs to meet the key players in these departments. So, it is important that meetings involve the other managers who report up to the C-level colleagues.

Informal meetings are actually far more important—they occur in hallways, telephone chats, lunches, and business trips—the off-the-record conversations that enable people to really understand how to create important relationships. If a C-level partner can count on the CIO—and sense that he or she understands the challenges they have in the organization, it really helps. Informal meetings cannot occur every six months—they occur all the time—and are typically event driven, that is, initiated by the CIO based on something that is going on inside the organization. If there is an opportunity to bring value, then a CIO should act on it—informally first! Informal discussions often lead to lasting relationships and even friendships, personal and business. These friendships do matter—remember that.

CIOs often err in thinking that all they need is a C-level partner to support them—it's not enough. Line managers, which we define as those managers who have daily production responsibilities, can be very influential and powerful within their own business domains. Knowing and working with line managers is critical—and thus forming relationships with them is equally as important. Furthermore, if line managers support IT, it only strengthens the relationship with the CIO's other C-level colleagues. So how does one do this? Work with a business C-level partner and get his or her authorization to start working directly with that person's direct managers. Do not do it alone; CIOs should enlist their line managers as well. Getting staff in line with their counterpart business manager shows that the IT organization has the depth and breadth to implement commitments to the business. Having strong IT line managers also affects how others view the CIO—lousy IT line managers equates to a lousy CIO. Remember the old cliché: “You're only as good as your people.”

Our final recommendation to CIOs is to always try to be helpful—people appreciate it. CIOs should engrain this concept within their staff and make it a vital part of the IT way of doing business.

11. Drive Profitability

The more the CIO can strategically support the organization to drive more profits, the more valuable the function. The more valuable a CIO is to the organization, the more capacities and power will be afforded to the role.

We discussed the importance of having a seat at the table. This usually means reporting to the CEO directly and being engaged at all key meetings in the firm. But it also means presenting to their board of directors, the ultimate “seat” of exposure. Driving profits starts with delivering ideas and getting support to implement them. We are not advocating that CIOs become overnight marketing gurus. So profits for CIOs are generating related solutions like what Passerini offered at Procter & Gamble or Koster at Prudential. Most of what they accomplished was how they delivered their ideas at senior management meetings or at board events.

So what are the key issues that CIOs need to think about before and at a board meeting? What are boards interested in discussing? After a number of conversations with leading CIOs and with board members the current consensus is as follows:

- Boards are less interested in reviewing the budget as they are about ideas and ways the CIO can assist the organization's growth, both operationally and strategically.

- Boards are concerned about security—how the CIO is providing protection against security risks and exposures of confidential information.

- Boards are now aware of the dangers and risks of the data the organization stores. A new and emerging area of CIO responsibility is known as “e-discovery.” This involves the understanding of how much data is available and the legal exposures of saving such information.

- Boards need to understand the data they have. The CIO needs to do more with “data analytics,” the interpretation of the information that an organization has and what it means.

How, then, do CIOs present these issues to their board? Here are some tips:

- Do research about all board members. What is their background? What do they tend to focus on? Speak with other executives who have presented to the board in the past; they may be able to provide tips and suggestions about how the board meeting tend to be conducted.

- Try to get to know your board members and attempt to speak and meet with them before the actual board meets. This will allow you to ascertain what they are thinking and what issues appear to be at the top of their individual agendas. They may also help you to “sell” your ideas to other board members.

- Board meetings tend to run longer than scheduled, and the presentation time may be significantly reduced. Therefore, CIOs need to ensure that they have multiple versions of their presentation, that is, one that can be presented within time limits.

- Tell stories and keep it simple. Try to express your needs through a story of how the organization can excel as a result of your efforts and operations. Stories that show how success can be attained are very attractive to getting board attention.

CIOs should be direct with their board. Do not speak in vague terms, and take responsibility for problem areas. Always articulate the plans designed to fix the problems and do not blame IT staff for what is ultimately the CIO's responsibility.

In our experience, many CIOs think their boards of directors want them to focus on costs and budgets. If they want a better understanding of board expectations, they should take some guidance from Virginia Gambale, who has long experience on both sides of the fence.

What directors really value in a CIO is sound strategic thinking and a great ability to execute, says Gambale, a former CIO at Merrill Lynch, Bankers Trust, and Alex Brown, and former partner at Deutsche Bank Capital. Gambale said boards expect the CIO to provide guidance on how technology can improve the firm's growth and market strength, help the company better reach customers and develop innovations that boost market share. CIOs should practice “using the language of the board,” she said. CIOs must talk about things like asset allocation, distribution channels, not technology itself. “Encase yourself in corporate strategy,” she said. “Stay away from talking about the plumbing, and no technical jargon, for sure.”

We asked Gambale how a CIO can best learn the language of the board. She urges CIOs to create close business relationships with their CFO, head of corporate strategy, and product development executives so they can understand the operating model of the company and clearly grasp what drives profitability. For example, at JetBlue, profitability is heavily dependent on the costs of fuel, labor, and airplanes.

12. Use Benchmarks

Having statistical analysis of the IT operations is still very important, certainly in supporter functions. CIOs need to show they use metrics to optimize the performance or their organizations.

Other members of the C-suite are accustomed to achieving best practices through industry benchmarking. It is difficult to determine whether the IT operation is performing to peak capacities without having some evidence of related performances of others in the industry and trades. Benchmarking data is typically available from CIO organizations as well as from industry organizations. The IT department should be required to participate in all aspects of benchmarking conversations with other business units as well.

Another excellent benchmark organization is ISO 9000. Many IT departments have utilized ISO 9000 concepts; ISO stands for the International Standards Organization, a worldwide organization that defines quality processes through very formal structures. It attempts to take knowledge-based information and transfer it into specific and documented steps that can be evaluated as they occur. Unfortunately, the ISO 9000 approach, even if realized, is challenging when such knowledge and procedures are undergoing constant and unpredictable change.

13. React to the Dynamics of the Market

We discussed Bradley and Nolan's concept of sense and respond. It is clear from our cases that successful CIOs understand that they cannot know the future and need to be very agile to changes in the market that affect their organization.

CIOs need to be good businesspeople. As such, they must understand how markets affect their world in IT. We spoke earlier of the notions of an S-curve and how it dictates indirectly how IT is viewed and measured. Furthermore, the S-curve is the basis of whether an IT initiative is at the driver or supporter phase. Responsive organizational dynamism needs to also be at the forefront of all CIO decisions, but the state of the market is most important. If there is anything we have learned it is that the market is vey unpredictable. As such, CIOs must deal with a world of unpredictability. Thus, CIOs need to adapt to the concept of sensing an opportunity and responding dynamically. That is, the world of planning, getting requirements, implementing, and then considering future enhancements is no longer relevant for most IT projects.

We expect the acceleration of change to continue and the life cycle of S-curves to shrink, simply meaning that IT projects will be drivers for less time, then transform into supporters and reach obsolescence quicker. However, this accelerated life cycle also means that there will be more S-curves—meaning more IT projects that can change the relationships between the buyer and the seller. The advent of more and shorter IT projects should excite IT leaders because it means more opportunities to drive business value and participate in the supply-demand aspects of the market.

Conclusion

This chapter has summarized the results of what CIOs do to become successful. The question now is how to establish best practices to provide a blueprint for CIOs to follow and, more important, to measure their progress. Chapter 6 provides such models that not only define the mature CIO, but also his or her counterparts, the CEO and the middle managers of the business units. Here we will provide “maturity arcs” that are based on human development methods of assessing leadership growth.

Notes

1 R. Kegan, In Over Our Heads: The Mental Demands of Modern Life (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1994).

2 R. M. Grant, “Prospering in Dynamically-Competitive Environments—Organizational Capability as Knowledge Integration,” Organization Science 7(4) (1996): 375–387; D. J. Collis, “Research Note—How Valuable Are Organizational Capabilities?” Strategic Management Journal 15 (1994): 143–152; Mark Dodgson, “Organizational Learning: A Review of Some Literatures,” Organizational Studies 14(3) (1993): 375–394.

3 A. M. Langer, “Fixing Bad Habits: Integrating Technology Personnel in the Workplace Using Reflective Practice,” Reflective Practice 2(1) (2001): 100–111.

4 D. Grant, T. Keenoy, and C. Oswick (Eds.), Discourse and Organization (London: Sage, 1998).

5 A. M. Langer, Information Technology and Organizational Learning: Managing Behavioral Change through Technology and Education, 2nd ed. (Boca Raton, FL: Taylor and Francis, 2011).

6 W. Pietersen, Reinventing Strategy: Using Strategic Learning to Create and Sustain Breakthrough Performance (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2002).

7 J. Deluca, Political Savvy: Systematic Approaches to Leadership Behind-the-Scenes (Berwyn, PA: EBG, 1999).

8 Ibid., p. xiv.

9 Ibid., p. xii.

10 Joe D. Batten, Tough-Minded Management, 3rd ed. (Eugene, OR: Resource Publications, 2002).

11 O. C. Ferrell, and Gareth Gardiner, In Pursuit of Ethics: Tough Choices in the World of Work (Springfield, IL: Smith Collins, 1991).

12 Langer, “Fixing Bad Habits.”

13 R. W. Eichinger and M. M. Lombardo, “Education Competencies: Dealing With Ambiguity,” Microsoft in Education, Training, www.microsoft.com/education/en-us/Training/Competencies/Pages/dealing_with_ambiguity.aspx.

14 J. Conger, in L. Keller Johnson, “Exerting Influence without Authority,” Harvard Business Update (Boston: Harvard Business Press, 2003).

15 Langer, Information Technology and Organizational Learning.

16 Thomas L. Friedman and Michael Mandelbaum, That Used to Be Us: How American Fell Behind in the World It Invented and How We Can Come Back (New York: Picador, 2012).

17 C. K. Prahalad, and M. S. Krishnan, The New Age of Innovation: Driving Cocreated Value through Global Networks (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2008).

18 E. H. Schein, Organizational Culture and Leadership, 2nd ed. (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1992).

19 E. Wenger, (1998) Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning and Identity (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press).

20 B. Elkjaer, “In Search of a Social Learning Theory.” In M. Easterby-Smith, J. Burgoyne, and L. Araujo (Eds.), Organizational Learning and the Learning Organization (London: Sage Publications, 1999), 75.

21 H. C. Lucas, Information Technology and the Productivity Paradox (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999).

22 D. J. Teece, “Strategies for Managing Knowledge Assets: The Role of Firm Structure and Industrial Context.” In I. Nonaka and D. Teece (Eds.), Managing Industrial Knowledge: Creation, Transfer and Utilization London, UK: Sage, 2001), 125–144.

23 T. Bertels and C. M. Savage, “Tough Questions on Knowledge Management.” In G. V. Krogh, J. Roos, and D. Kleine (Eds.), Knowing in Firms: Understanding, Managing and Measuring Knowledge (London: Sage, 1998).

24 I. Nonaka and H. Takeuchi, The Knowledge-Creating Company: How Japanese Companies Create the Dynamics of Innovation (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), 3.