The Production Process: Preproduction

The production process is most easily understood and organized by its three steps: preproduction, production, and postproduction. Each step involves specific functions and operations that are critical to the final production.

Before any serious work can begin on a video project, a source of funding must be found. An interested party must commit money for staff, crew, cast, research, facilities, equipment, and expendable materials. Such sources of funds may be clients who have contracted for the specific project, such as television stations or networks, cable networks, or funding agencies; government agencies; money-lending agencies, such as banks and savings and loan companies; or insurance companies.

Proposal

Regardless of the funding source, there is common information that must be supplied to gain access to such funding. The first document of the preproduction process is called a proposal. A proposal generally is the responsibility of the producer, but it is better to prepare it with the assistance of the writer(s) and director. Considerable knowledge of the subject is imperative to avoid mistakes, misinformation, or serious inaccuracies. A complete site survey, interviews, and library and other research must be carried out before the proposal can be written.

After the research has been completed, all of the information is organized into a concise, meaningful package that briefly explains the objectives of the production, the target audience, and the distribution methods. Key production factors, basic style and genre, unusual production techniques, and special casting and location considerations, together with the length, recording format, and release format, all need to be explained in easily understandable lay terms. The proposal writer must be accurately aware of how the completed production is to be distributed, such as on videotape; broadcast or cablecast; or converted to a digital format on tape, CD-ROM, or computer disc. The proposal writer must understand that the person reading the proposal and making a funding judgment may not have a media background. The proposal must be written so that all aspects of the production are presented clearly, avoiding production jargon.

An approximate timeline and budget complete the proposal package. Both of these should be prepared carefully and realistically. Too much or too little of either can discourage a client or funding source. Worse yet, a miscalculation in either section can place the producer in a position in which it is impossible to complete the project because of insufficient funds or time.

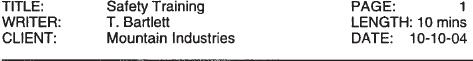

Rivers and Streams Productions, Inc. will produce a ten minute, color videotape to be used as a training medium for new and present employees of Mountain Industries. The tape will target specific safety procedures necessary to be followed in the unique operation of logging In the mountains of Montana. The tape will emphasize personal safety actions and procedures required by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

The shooting schedule will last for ten days, weather and other acts of nature notwithstanding. Postproduction will last for four weeks following the completion of principal videography. Taping will start within two weeks of final script approval. Research and preparing of the treatment will last three weeks following the acceptance of the proposal. The final script will be prepared within three weeks of acceptance of the proposed treatment.

The budget will be approximately $35,000.00, depending on specific technical requirements of the script. Because the script calls for a series of dangerous actions requiring stunt actors and technicians, some allowances for costs and shooting overruns may be required.

The format will be semi-documentary/instructional with the tape narrated and techniques explained by an actor representing a skilled and knowledgeable logger. Both incorrect and correct operational procedures will be illustrated. Employees, equipment, and facilities of Mountain Industries logging operation will be required for the production of this tape.

Treatment

After the proposal has been written, a treatment must be prepared. A treatment is a narrative description of the production. Like the proposal, the treatment is intended to be read by the potential financial backers to assist them in making the decision as to whether they are willing to entrust their money to the producer.

The first paragraph of the treatment repeats key information from the proposal: title, length, format, and objective of the production. The treatment should be written as if the writer is describing what he or she sees when watching a playback of the completed production. Dialogue is not used, but indications of the type of conversations or narration should be included. Also, technical terminology such as “dissolve,” “medium close-up,” and “voice-over” should be avoided. Remember, the person reading the document is not a media professional. The proposal and treatment are essentially sales tools designed to sell your ability to successfully complete your production within budget and on time, while accomplishing the stated objective.

The potential financial backers should be able to easily read and understand the proposal and treatment. They should be able to imagine exactly what the production will sound and look like without any other explanation or verbal description by the producer.

In reality, both the proposal and treatment may be written after the script has been finalized, because they must accurately reflect the script. From a practical point of view, the three preproduction writing functions may be prepared simultaneously.

Scene Script

The first completed draft of a script, the scene script, includes a detailed description of each scene and the action occurring during that scene, but not specific shots. Each scene description should indicate whether the scene is set during the day or at night and in an interior or exterior setting. The description should also describe the characters, key furniture/objects present, character movements, and all dialogue and narration.

Shooting Script

The shooting script is a more detailed version of the scene script. Each shot is described specifically and numbered in order. The framing—wide shot (WS), medium close-up (MCU), or close-up (CU)—is indicated, but the writer allows some leeway for the director’s creativity. The descriptions should be complete enough that the director is able to interpret accurately what the writer had intended in each sequence, scene, or shot.

The ten-minute training tape will open with a montage of incorrect logging operations followed in each case by the possible disastrous and life-threatening results of such actions. Examples of such scenes are:

A logger without a safety belt steps back and falls from a tree stand.

A chainsaw jams and flips back into the logger.

A tractor tips over on the driver because it exceeded its tilt limit.

A logging truck driven too fast forces an oncoming car from the road.

A log falls from a truck being loaded and strikes a logger who was standing too close to the truck.

A logger refuels his saw improperly, causing a fire.

A truck or tractor becomes a runaway when left improperly locked down.

A logger is dumped into the river and is crushed by logs.

A log avalanche occurs because of careless blocking of a log stack.

This series of accidents will be enhanced with sound effects and dramatic music as well as the actual sound of each accident.

Following this montage, the narrator will walk into the scene and describe in general the dangers and reasons for following OSHA safety requirements for those working in dangerous occupations such as the

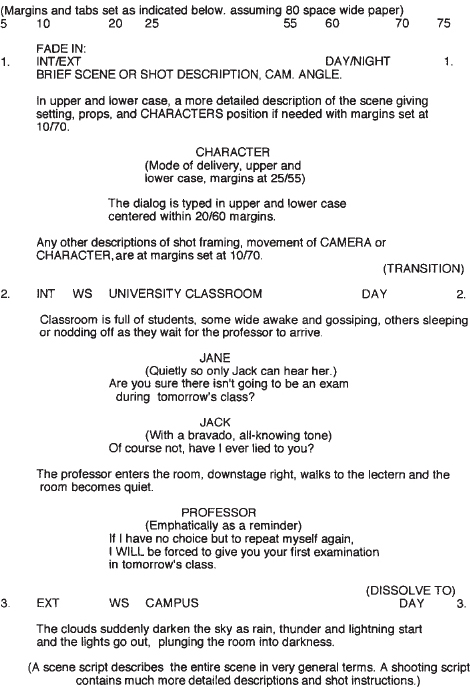

Two basic script formats are used in preparing scripts for electronic field production (EFP): the traditional film single-column format and the traditional television dual-column format.

The single-column format evolved from stage script format to motion picture format to radio format before it was adapted again for video productions. The format defines various aspects of the scripts by varying the width of the margins and by capitalizing certain portions of the copy. The rules at first seem complex, but they can be summarized as follows:

• Each shot starts with the shot number at the extremes of the right-and left-hand margins. In uppercase type, either the word DAY or NIGHT indicates lighting conditions, followed by either INT or EXT, to indicate location.

• Camera directions, scene descriptions, and stage directions appear next, within slightly narrower margins. How the line is to be delivered is typed in still narrower margins within parentheses, and dialogue is typed within even narrower margins.

• The name of the speaking character is centered above his or her line in uppercase letters.

• Single-spacing is used for dialogue, camera angles and movements, stage directions, scene descriptions, sound effects, or cues.

• Double-spacing is used to separate a camera shot or scene from the next camera shot or scene, a scene from an interceding transition (FADE IN/FADE OUT, DISSOLVE), the speech of one character from the heading of the next character, and a speech from camera or stage directions.

• Uppercase type is used for interior (INT) or exterior (EXT) in heading line; indication of location; indication of day (DAY) or night (NIGHT); name of a character when first introduced in the stage directions and to indicate the character’s dialogue; camera angles and movements; scene transitions; and indication of scene continuation (CONTINUED), if a scene is split between pages (avoid if at all possible).

MASTER SCREEN SCRIPT FORMAT

The dual-column television script format evolved from the audiovisual and instructional film formats. It is based on separating audio instructions and information from visual instructions. Two columns are set up on the page. The video instructions are located on the left side of the page, and the audio instructions are on the right side. This is not an absolute rule; some operations prefer the opposite, and some include a storyboard on the left, right, or down the middle of the page.

Each shot number is identified in both the video and audio columns, matching the appropriate audio with its video counterpart. All video and audio instructions are typed in uppercase letters. Copy to be read by the performers is typed in uppercase and lowercase letters. Many performers, especially news anchors, prefer all uppercase letters in the misguided belief that uppercase copy is easier to read. However, all readability studies indicate the opposite, and most computerized prompter systems currently display copy in both uppercase and lowercase letters.

Video instructions are arranged in single-spaced blocks, whereas audio copy is presented in double-spaced blocks. Triple-spacing between shots helps both the talent and the director follow the flow of the script. The name of the talent is typed in uppercase letters to the left of the right-hand column. If the same audio source continues through several shots, it is not necessary to repeat the source’s name unless another source intervenes.

Avoid hyphenating words at the end of a line and avoid splitting shots at the bottom of the page. Spreading copy out allows for notes and additional instructions to be added during actual production.

Information concerning the production should be repeated at the top of each page—for example, the title, writer’s name, and other pertinent information. Each page must be numbered in sequence. If pages are added, letters or other indications may be added to keep the pages in order (for example, page 25a falls between pages 25 and 26).

Computer programs have been designed to facilitate the preparation of scripts by allowing the writer to concentrate on the creative part of writing rather than the formatting. These computer applications are specifically designed for both single- and double-column scripts in a variety of formats, including television, audio/video, multimedia, motion pictures, and radio.

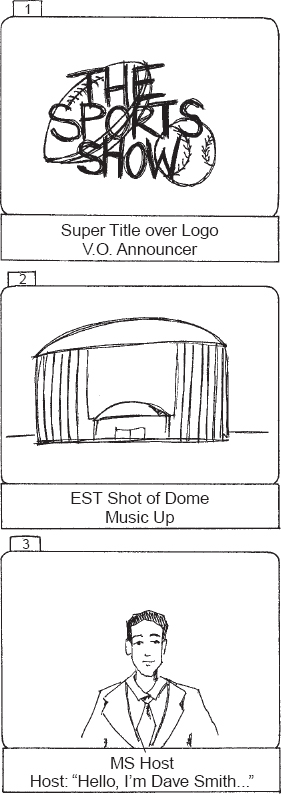

Storyboards are paper visualizations of the production. They provide a flexible means of working out sequences, framing, and shot relationships before bringing an expensive cast and crew together for the actual production. Storyboards are usually organized in three parts: picture, copy/instructions, and shot number.

Generally, a storyboard form displays a 4 : 3 or 16 : 9 area, with rounded corners, that contains the video frame, with a small space above the frame for writing in the shot number. Below the frame is an area, usually slightly smaller than the frame, designed to contain the audio and/or other specific instructions for that shot. Storyboard forms are available in preprinted packets or as a computer program template. Such templates allow the writer/artist to draw and redraw until the design is satisfactory without creating stacks of printed boards. Such templates may be passed among creative staff for alterations and feedback before the final script is created.

The key objects in the shot are sketched into the frame block. These visual representations can be as simple as stick figures or as accurate as color photographs. The more accurate the drawings, the more serviceable the storyboard will be in solving problems during preproduction and production. The matching space for instructions may contain “pan,” “dolly,” or other camera movement or composition concepts. The shot number must match the shot number on the script. If additions or deletions are made, then the shot number changes must be made to both the script and the storyboard. Each shot should be represented by at least one storyboard frame. In some cases, additional frames may be necessary to show beginning and ending frame positions if a pan, dolly, or zoom is indicated.

Once completed, storyboard frames can be placed on a wall or flannel board so that they can be rearranged easily. Standing back and looking at all of the storyboard frames gives the director, writer, and producer a better overall view of the production and can provide a way to spot problem areas or solutions to problems.

Because the storyboard frame, description, and shot number can be separated from other storyboard frames, their order can be manipulated until the best possible shot sequence is reached. This process may prevent continuity problems by avoiding jump cuts and may create a more organized method of shooting the production.

Once the complete storyboard order has been arranged, the final shooting script can be written.

A notion of the type of shooting location required should be determined early on in the production conceptualization process. Specific locations can be chosen after the scene script has been written, but the location must be finalized before the shooting script has been completed.

In addition to the obvious characteristics to look for in a location—accessibility and having the right setting or appearance—there are some factors that are less obvious. A location that can be used without cost, such as near parking, power, and sanitary facilities, and that is convenient to storage space for equipment and materials is worth the search. Access to temperature-controlled areas for cast and crew to use between takes is also important. Once a location has been chosen, arrange a meeting with the site authority.

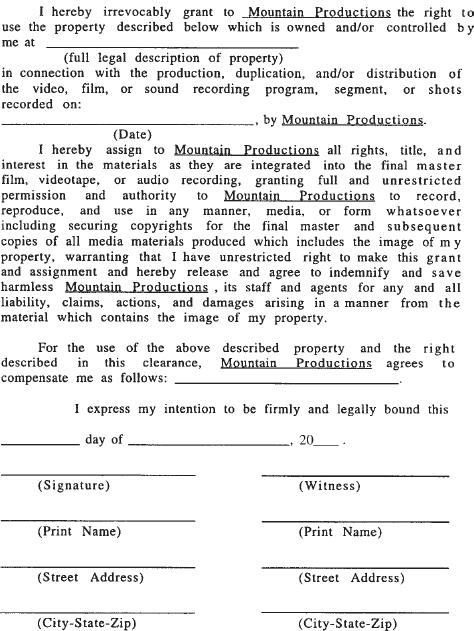

At this meeting, the following information must be collected: names, phone numbers, and exact location or addresses of authorities who control the areas and locations to be used. These individuals may be the resident, building engineer, building manager, janitor, department head, or a civil employee in charge of public areas. Make certain that the person who has given permission to use the location actually has the authority to do so and then get permission in writing with a location release.

While meeting with the site authority, the producer should explain fully how the site will be used, what changes may be necessary, how restoration will be handled, and what access the production crew will need to the location. Discuss every possible contingency that could occur during the production process to avoid any unresolved differences during actual production.

Put into writing all agreements, have the site authority sign them, keep copies, give the site authority copies, and send copies to the ultimate authority of the location. This should be done well before the shoot is scheduled so that any problems can be resolved before the cast and crew arrive for the shoot.

MOUNTAIN PRODUCTION LOCATION RELEASE

Site Survey and Location Planning

Be sure to visit the location at the time of day, day of the week, and, if possible, day of the month that the production will be shot. This precautionary act may help avoid hindrances such as unplanned traffic and noise, lighting, and ambient sound problems. Each room or space to be used should be measured accurately, and a scale drawing should be plotted indicating the locations and sizes of windows and doors and placement of furniture, walls, and power sources. In addition to the location of power outlets, the location of the fuse or circuit breaker box should be determined. Discuss with the site authority whether you may tap into the fuse box or if it can be left open in case a fuse or breaker blows. If the box is left open, the crew can correct problems without waiting for the box to be unlocked or handled by an assigned person. While checking the location of the fuse box, check the power rating of each circuit and determine which circuits control specific outlets that may be used for the shoot.

After all of the measurements have been taken and the plot is drawn, then possible locations for performers and cameras should be identified. Note the movements of the performers, as well as camera movements. If furniture needs to be moved or extra furniture or set pieces are required, this should be indicated on the plot. The plot is a scale diagram drawn as if you are looking straight down on the location. It is not drawn in perspective and is useless if not drawn to an accurate scale.

Before leaving the site meeting, determine from the site authority where production vehicles may be safely and legally parked and the location of a loading area. When possible, choose a loading/parking location that is well lit and has some security. If the location does not provide security for vehicles, it may be necessary to hire or provide your own security personnel. If permits for parking and/or loading are required, determine the process and authority for obtaining such permits. Keep in mind that not even public property can be used for any production purpose without permission, a permit, and often a fee.

Before leaving the site during the survey, recheck all of the information gathered and make certain that you have all the necessary facts, permits, measurements, and telephone numbers. Make sure that there are no conflicts or contradictions in your lists.

SITE PLOT SAMPLE

Once the site survey has been completed, the director, camera operator, gaffer, and audio operator meet to list the equipment required for the shoot. If possible, these three key crew members should accompany the director on the site survey. Each crew chief is responsible for the equipment needed to fulfill his or her responsibilities, but a production meeting should be held to double-check all aspects of the production and to provide an opportunity for an exchange of ideas, solutions to problems, and resolutions to unanswered concerns.

Making a list of equipment helps ensure that everything has been thought of that will be needed. It can also be used as a checklist when packing up the equipment to make certain that nothing has been left behind at the end of the shoot. The director confers with the crew chiefs on the skills and number of crew members required. Most EFP shoots are organized with the intention of using a minimum number of people, but the complexity of the production determines the size of the crew.

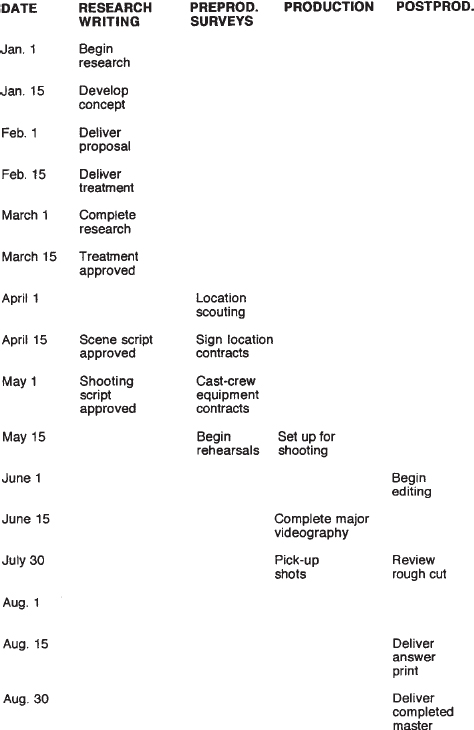

Once all the lists are completed, the director and producer work out a detailed schedule that starts with that day and ends with the delivery of the finished product. Each stage of the production should be organized on a timeline designed so that each stage can proceed independently, and therefore will be unaffected by delays in other stages. However, the interdependency of media production also makes a timeline critical in the efficient completion of any project.

With the completed shooting script and plot in hand, the director can sit down at the site later and determine which shots are to be made from each camera location. The director should indicate on a shooting list (shot sheet) which shots are to be shot at each camera location and the order in which they are to be shot. The most efficient use of cast, crew, and equipment should be the key factor in this determination. Make certain that all possible shots are planned from each location before the camera and lights are moved to the next location.

TIMELINE PLOT