Hour 6. Working with Fonts

In the previous hour, you learned the basics of creating blocks of text and putting that text into list format. In this hour, you’ll take a closer look at the bits of text themselves, and learn how to change the visual display of the font—it’s font family, size, and weight, for example. You’ll learn to incorporate boldface, italics, superscripts, subscripts, and strikethrough text into your pages. You will also learn how to change typefaces and font sizes.

Note

When viewing other designers’ web content, you might notice methods of marking up text that are different than those taught in this book. The “old way” of formatting text includes the use of the <b></b> tag pair to indicate when a word should be bolded, the <i></i> tag pair to indicate when a word should be in italics, and the use of a <font></font> tag pair to specify font family, size, and other attributes. However, there is no reason to learn it because it is being phased out of HTML, and CSS is considerably more powerful.

Boldface, Italics, and Special Text Formatting

Way back in the age of the typewriter, we were content with plain-text and an occasional underline for emphasis. Today, boldface and italic text have become de rigueur in all paper communication. Naturally, you can add bold and italic text to your web content as well. There are several tags and style rules that make text formatting possible.

Note

An alternative to style rules when it comes to bold and italic text involves the <strong></strong> and <em></em> tag pairs. The <strong> tag does the same thing as the <b> tag in most browsers, whereas the <em> tag acts just like the tag <i> by formatting text as italics.

The <strong> and <em> tags are considered by some to be an improvement over <b> and <i> because they imply only that the text should receive special emphasis, rather than dictating exactly how that effect should be achieved. In other words, a browser doesn’t necessarily have to interpret <strong> as meaning bold or <em> as meaning italic. This makes <strong> and <em> more fitting in XHTML because they add meaning to text, along with affecting how the text should be displayed. All four tags remain part of HTML 5, although their use becomes slightly more nuanced.

The “old school” approach to adding bold and italic formatting to text involves the <b></b> and <i></i> tag pairs. For boldface text, put the <b> tag at the beginning of the text and </b> at the end. Similarly, you can make any text italic by enclosing it between <i> and </i> tags. Although this approach still works fine in browsers and is supported by XHTML, it isn’t as flexible or powerful as the CSS style rules for text formatting.

Although you’ll learn much more about CSS style rules in Part III, it’s worth a little foreshadowing just so you understand the text formatting options. The font-weight style rule allows you to set the weight, or boldness, of a font using a style rule. Standard settings for font-weight include normal, bold, bolder, and lighter (with normal being the default). Italic text is controlled via the font-style rule, which can be set to normal, italic, or oblique. Style rules can be specified together if you want to apply more than one, as the following example demonstrates:

![]()

In this example, both style rules are specified in the style attribute of the <p> tag. The key to using multiple style rules is that they must be separated by a semicolon (;).

You aren’t limited to using font styles in paragraphs, however. The following code shows how to italicize text in a bulleted list:

You can also use the font-weight style rule within headings, but a heavier font usually doesn’t have an effect on headings because they are already bold by default.

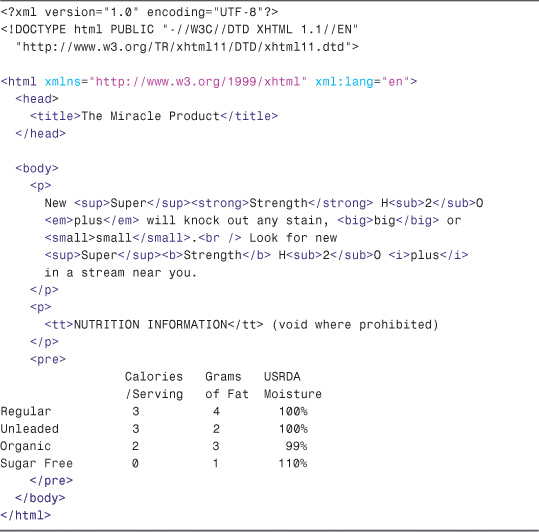

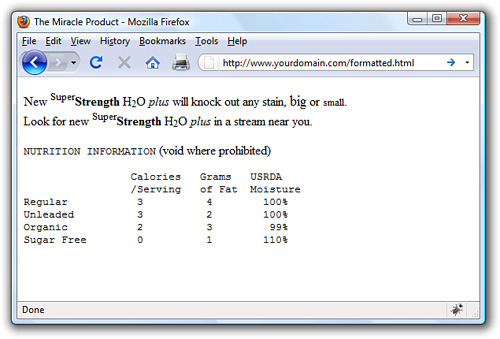

Although using CSS allows you to apply richer formatting, there are a few other HTML tags that are good for adding special formatting to text when you don’t necessarily need to be as specific as CSS allows you to be. Following are some of these tags. Listing 6.1 and Figure 6.1 demonstrate each tag in action.

• <small></small>—Small text

• <big></big>—Big text; not present in HTML 5 because text size is better controlled by CSS.

• <sup></sup>—Superscript text

• <sub></sub>—Subscript text

• <em></em> or <i></i>—Emphasized (italic) text

• <strong></strong> or <b></b>—Strong (boldface) text

• <tt></tt>—Monospaced text (typewriter font); not present in HTML 5 because font appearance is better controlled by CSS.

• <pre></pre>—Monospaced text, preserving spaces and line breaks

Listing 6.1 Special Formatting Tags

Figure 6.1 Here’s what the character formatting from Listing 6.1 looks like.

Warning

There used to be a <u> tag for creating underlined text, but there are a couple of reasons not to use it now. First off, users expect underlined text to be a link, so they might get confused if you underline text that isn’t a link. Secondly, the <u> tag is deprecated, which means that it has been phased out of the HTML/XHTML language, as has the <strike> tag. Both tags are still supported in web browsers and likely will be for quite a while, but using CSS is the preferred approach to creating underlined and strikethrough text. In HTML 5, deleted text can be surrounded by the <strike><strike> tag pair, which will render as text with a strikethrough.

The <tt> tag usually changes the typeface to Courier New, a monospaced font. (Monospaced means that all the letters and spaces are the same width.) However, web browsers let users change the monospaced <tt> font to the typeface of their choice (look on the Options menu of your browser). The monospaced font might not even be monospaced for some users, though the vast majority of users stick with the standard fonts that their browsers show by default.

The <pre> tag causes text to appear in the monospaced font, but it also does something else unique and useful. As you learned in Hour 3, multiple spaces and line breaks are normally ignored in HTML files, but <pre> causes exact spacing and line breaks to be preserved. For example, without <pre>, the text at the end of Figure 6.1 would look like the following:

![]()

Even if you added <br /> tags at the end of every line, the columns wouldn’t line up properly. However, when you put <pre> at the beginning and </pre> at the end, the columns line up properly because the exact spaces are kept—no <br /> tags are needed. The <pre> tag gives you a quick and easy way to preserve the alignment of any monospaced text files you might want to transfer to a web page with minimum effort.

CSS provides you with more robust methods for lining up text (and doing anything with text, actually), and you’ll learn more about them throughout Part III.

Tweaking the Font

The <big>, <small>, and <tt> tags give you some rudimentary control over the size and appearance of the text on your pages. However, there might be times when you’d just like a bit more control over the size and appearance of your text. Before I get into the appropriate way to tinker with the font in XHTML code, let’s briefly take a look at how things were done prior to CSS because you might still find examples of this method when you look at the source code for other web sites. Remember, just because these older methods are in use doesn’t mean you should follow suit.

Before style sheets entered the picture, the now phased-out <font> tag was used to control the fonts in web page text. For example, the following HTML will change the size and color of some text on a page:

![]()

As you can see, the size and color attributes of the <font> tag made it possible to alter the font of the text without too much effort. Although this approach worked fine, it was replaced with a far superior approach to font formatting, thanks to CSS style rules. Following are a few of the main style rules used to control fonts:

• font-family—Sets the family (typeface) of the font.

• font-size—Sets the size of the font.

• color—Sets the color of the font.

Note

You’ll learn more about controlling the color of the text on your pages in Hour 9, “Working with Colors.” That hour also shows you how to create your own custom colors and how to control the color of text links.

The font-family style rule allows you to set the typeface used to display text. You can and usually should specify more than one value for this style (separated by commas) so that if the first font isn’t available on a user’s system, the browser can try an alternative. You’ve already seen this in previous lessons. Providing alternative font families is important because each user potentially has a different set of fonts installed, at least beyond a core set of common basic fonts (Arial, Times New Roman, and so forth). By providing a list of alternative fonts, you have a better chance of your pages gracefully falling back on a known font when your ideal font isn’t found. Following is an example of the font-family style used to set the typeface for a paragraph of text:

![]()

There are several interesting things about this example. First, arial is specified as the primary font. Capitalization does not affect the font family, so arial is no different from Arial or ARIAL. Another interesting thing about this code is how single quotes are used around the times roman font name because it has a space in it. However, since 'times roman' appears after the generic specification of sans-serif, it is unlikely that 'times roman' would be used. Because sans-serif is in the second position, it says to the browser “if Arial is not on this machine, use the default sans-serif font.”

The font-size and color style rules are also commonly used to control the size and color of fonts. The font-size style can be set to a predefined size (such as small, medium, or large) or you can set it to a specific point size (such as 12pt or 14pt). The color style can be set to a predefined color (such as white, black, blue, red, or green) or you can set it to a specific hexadecimal color (such as #FFB499.) Following is the previous paragraph example with the font size and color specified:

![]()

Note

You’ll learn about hexadecimal colors in Hour 9. For now, just understand that the color style rule allows you to specify exact colors beyond just using green, blue, orange, and so forth.

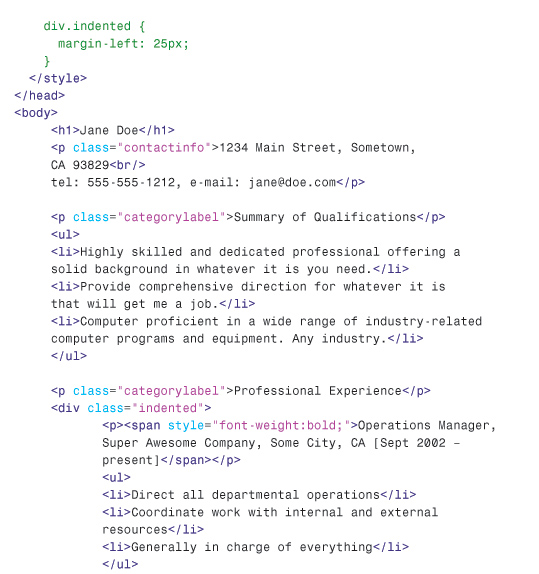

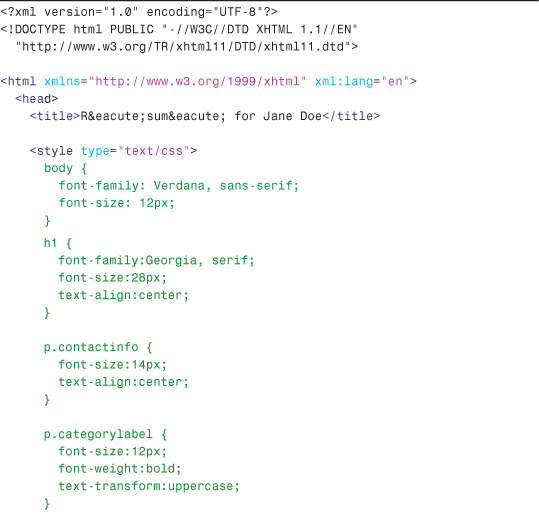

The example web content in Listing 6.2 and shown in Figure 6.2 uses some font style rules to create the beginning of a basic online résumé.

Listing 6.2 Using Font Style Rules to Create a Basic Résumé

Figure 6.2 Here’s what the code used in Listing 6.2 looks like.

Using CSS, which organizes sets of styles into classes—as you learned in Hour 4—you can see how text formatting is applied to different areas of this content. If you look closely at the definition of the div.indented class, you will see the use of the margin-left style. This style, which you will learn more about in Part II, applies a certain amount of space (25 pixels, in this example) to the left of the element. That space accounts for the indentation shown in Figure 6.2.

Working with Special Characters

Most fonts now include special characters for European languages, such as the accented é in Café. There are also a few mathematical symbols and special punctuation marks, such as the circular ![]() bullet.

bullet.

You can insert these special characters at any point in an HTML document using the appropriate codes shown in Table 6.1. You’ll find an even more extensive list of codes for multiple character sets at http://www.webstandards.org/learn/reference/named_entities.html.

Table 6.1 Commonly Used English Language Special Characters

For example, the word café could be written using either of the following methods:

café

café

Although you can specify character entities by number, each symbol also has a mnemonic name that is often easier to remember.

Tip

Looking for the copyright © and registered trademark ® symbols? Those codes are © and ®, respectively.

To create an unregistered trademark ™ symbol, use ™.

HTML/XHTML uses a special code known as a character entity to represent special characters such as © and ®. Character entities are always specified starting with & and ending with ;. Table 6.1 lists the most commonly used character entities, although HTML supports many more.

Table 6.1 includes codes for the angle brackets, quotation, and ampersand. You must use those codes if you want these symbols to appear on your pages; otherwise, the web browser interprets them as HTML commands.

In Listing 6.3 and Figure 6.3, several of the symbols from Table 6.1 are shown in use.

Listing 6.3 Special Character Codes

Figure 6.3 This is how the HTML page in Listing 6.3 looks in most web browsers.

Summary

In this hour you learned how to make text appear as boldface or italic and how to code superscripts, subscripts, special symbols, and accented letters. You saw how to make the text line up properly in preformatted passages of monospaced text and how to control the size, color, and typeface of any section of text on a web page.

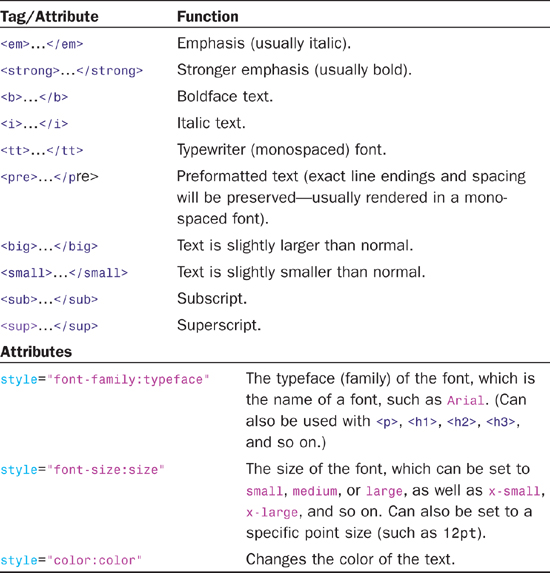

Table 6.2 summarizes the tags and attributes discussed in this hour. Remember that all the HTML tags are listed in Appendix B, “XHTML 1.1 and CSS 2 Quick Reference.”

Table 6.2 HTML Tags and Attributes Covered in Hour 6

Q&A

Q How do I find out the exact name for a font I have on my computer?

A On a Windows or Macintosh computer, open the Control Panel and click the Fonts folder—the fonts on your system are listed (Vista users might have to switch to “Classic View” in your Control Panel). When specifying fonts in the font-family style rule, use the exact spelling of font names. Font names are not case-sensitive, however.

Q How do I put Kanji, Arabic, Chinese, and other non-European characters on my pages?

A First of all, users who need to read these characters on your pages must have the appropriate language fonts installed. They must also have selected that language character set and its associated font for their web browsers. You can use the Character Map program in Windows (or a similar program in other operating systems) to get the numerical codes for each character in any language font. To find Character Map, click Start, All Programs, Accessories, and then System Tools. If the character you want has a code of 214, use Ö to place it on a web page. If you cannot find the Character Map program, use your operating system’s built-in Help function to find the specific location.

The best way to include a short message in an Asian language (such as We Speak Tamil—Call Us!) is to include it as a graphics image. That way every user will see it, even if they use English as their primary language for web browsing. But even to use a language font in a graphic, you will likely have to download a specific language pack for your operating system. Again, check your system’s Help function for specific instructions.

Workshop

The workshop contains quiz questions and activities to help you solidify your understanding of the material covered. Try to answer all questions before looking at the “Answers” section that follows.

Quiz

1. How would you create a paragraph in which the first three words are bold, using styles rather than the <b> or <strong> tags?

2. How would you represent the chemical formula for water?

3. How do you display “© 2009, Webwonks Inc.” on a web page?

Answers

![]()

2. You would use H<sub>2</sub>O.

![]()

3. You would use either of the following:

![]()

Exercises

• Apply the font-level style attributes you learned about in this chapter to various block-level elements such as <p>, <div>, <ul>, and <li> items. Try nesting your elements to get a feel for how styles do or do not cascade through the content hierarchy.