CHAPTER 8

Hit Refresh

But doth suffer a sea-change,

Into something rich and strange.

William Shakespeare, The Tempest

Introduction

In summer 2005, three great minds came together to launch a podcasting platform. They had set up a product that would convert a phone call into .mp3 format and host it on the internet. The firm was called Odeo, and they even got funded for their product from VC investors. However, within a few weeks of launching the product, the mighty Apple announced iTunes would be rolled out with their iPods.

The founders of Odeo knew they had to act because their product wasn't seeing much traction. They had to reinvent themselves to stay relevant. The organisation of 14 employees came together to brainstorm ideas on how they could get out of jail. One of the top employees of the firm, Jack Dorsey, came up with the idea of creating an app in which people could share their status. It took until February 2006 for the idea to resonate with the rest of the management team.

The idea was named Twttr initially and then ended up becoming Twitter. Although the idea came from Jack Dorsey, the efforts to make it happen were led by Noah Glass in the initial days. Jack Dorsey and Evan Williams were still involved in moving the project forward. By March 2006, Twitter's prototype was ready. Twitter's own employees found the product increasingly addictive. In summer 2006, when an earthquake hit San Francisco, it became the first major product validation moment because several people used Twitter to spread the word of the earthquake.

Once Twitter had about 5000 users, Odeo's investors, who had chipped in with about $5 million, were notified about it by Evan Williams. He wrote to them saying that the podcast application wasn't taking off, and therefore he was happy to buy back the shares of Odeo and make it even with the investors. He had also mentioned about the Twitter project in the investor communication and highlighted that it was still early days for the project. Investors were happy to get their money back.

Twitter's founding team went through some reshuffling and rebranding after that transaction and rose to the tech giant we know today. In some ways, Twitter could be one of the most successful pivots in the history of technology startups. A pivot doesn't necessarily need to be as drastic as the Odeo–Twitter transition. It could be a more modest course correction.

Irrespective of the nature of the pivot, a decision to do so comes from a good understanding of the landscape the startup is operating in, consumer uptake and the potential upside post-pivot. Most of all it also requires a lot of self-awareness if not humility from the founders to look inward when things don't quite work to plan and chart out a course correction.

At the start of the first-order optimisation process, we discussed the startup bell curve. We looked at three categories of startup. One category comprised those that benefited from a crisis. The second category and the ones that formed the bulge of the bell curve were ones that still were relevant, but saw a dip in revenues and cash flows. The third category of startup was ones that were made irrelevant due to the crisis.

In the previous chapters, we largely focussed on the middle part of the startup bell curve, which is the group of startups that have challenges growing during a crisis. In this chapter, we will look at the tail of the bell curve: startups that are mostly irrelevant due to market shifts that are outside their control.

We will look at what options these startups have through the third-order optimisation process. This involves a detailed discussion on how to assess if they have to seriously consider a pivot. We also cover what would typically constitute a pivot. Beyond pivots, this chapter also touches on the key strategic and operational habits a startup could develop to be sustainable through economic dips. Let us look at some ways of confirming that you might need to look at pivoting.

Third-Order Optimisation

In Chapter 5, we looked at ways a startup can look to acquire customers. We have several distribution channels that startups can use to acquire and onboard customers. With a focussed approach, they should be able to identify their core distribution channel and support channels. However, during a crisis, markets might drift in different directions and that could affect the success rates of your acquisition and retention of customers.

We will need a scientific approach to assessing if a pivot is needed. Through this book, we have come up with several original, yet simple, frameworks and mental models. There is already a holistic framework that can help you spot the need for a pivot. The model that can help measure and monitor customer traction is called the AARRR model, also known as the pirate metrics. The model was first proposed by Dave McClure, the founder of 500 startups.

The Pirate Metrics

AARRR stands for acquisition, activation, retention, referral and revenues. Acquisition is the process of wooing customers to your product and taking them through the journey to sign up. Activation is about getting past the sign-up process and giving customers their first product experience, climaxing with the ah-ha moment. This is precisely when customers realise that the product is what they needed and perhaps didn't even know beforehand.

The acquisition doesn't necessarily mean that the customer is actively using your product; activation is what identifies and actuates customer use. Depending on the type of product, acquisition might be more important than activation. Activation is also correlated with the next step: retention. A customer who has signed up and used the product is less likely to churn; therefore, retention identifies the subset of your customer base that you have kept versus the ones you have lost.

Retention is considered a very important metric for growth. If you are acquiring and activating at a fast pace, but have a high churn rate, then you are using a leaky bucket to fetch water. Acquiring customers can be compounded if you have a good referral rate. If you want to put your growth on steroids, come up with a very good referral plan and execute it.

If you are a B2C business, keep an eye on the ‘viral coefficient’, which is the number of new customers that an existing customer brings to you. If your viral coefficient is less than one, then the referrals are not going to bring virality. But if every customer brings in two customers, the compounding effect it has should put your growth on steroids. To create a sticky ecosystem to ensure retention, have a ‘frequent flyer’ programme to reward loyal customers, but most importantly, have a killer product suite that customers can't live without.

With growth and use in place, it is now time to focus on the viability and sustainability of the business and bringing in revenues. You need to find a way to monetise the growth that you have managed. Once you have identified monetisation, it is then about fine-tuning it. Here we start looking at lifetime value (LTV) and cost of acquisition of customers (CAC). The LTV-to-CAC ratio can help you optimise customer traction.

We cannot offer prescriptive measuring techniques that can scale industries and product lines. Depending on the type of business you run, you might have to use this framework to identify the right operational numbers that reflect the health of the pirate metrics. If you had this setup in place and have regular number crunching and reporting, that would help determine when your product is no longer relevant.

As a crisis sets in, the first metric that would typically dry up is revenue as customers become cost-sensitive. Consumers typically kill their subscriptions to products and services that they don't ‘need’ in times of crisis. I have done it in the past myself when a sudden financial crisis hit my life and I had to sustain.

A pivot scenario really comes in when use and retention falls. If you have a freemium model, customers can downgrade their membership and still use your product. Therefore, it might be useful to understand behavioural changes so that you can assess the degree of pivoting required. A crisis can sometimes kill all these metrics. Let us now look at the different types of pivot you could consider.

Shades of Grey

Pivoting doesn't necessarily mean you shut down everything you are doing and start from scratch again. The transition from Odeo to Twitter can arguably be viewed as starting a new company. But in my opinion, it was a proper pivot. Post the pivot came a rebranding and reshuffle at the top, depending on who really believed in the Twitter use case.

Therefore, pivots can come in different shades and shapes. Through the COVID-19 crisis one of my portfolio companies cut down their product suite to focus on just one product and another firm killed one business line altogether and focussed on another. Some ways that firms can pivot are as follows:

- Targeting a new market

- Targeting a new industry

- Changing the revenue model

- Focussing on a subset of your product suite

- Switching focus from one product line to another

- Expanding the breadth of product to make it more generic

- Using a new technology

- Using a new go-to market strategy

Let us quickly look at the second-order optimisation criteria to think through the considerations before you decide to pivot. As mentioned previously, you go through this process only when your AARRR (pirate metrics) have turned hopeless.

Consumer behaviour alignment needs to be tested through the pivoting process. Identify the metrics you want to capture to gain comfort that the pivot is gaining traction. My portfolio firm FrontM, which has a platform for remote communication and collaboration, was focussing on airlines and maritime before COVID-19 hit us. Their platform allowed for seamless development of AI and Edge-based applications for these industries.

Before COVID-19 they focussed on e-commerce and transactional applications. The assumption was that airline passengers would perform transactions in-flight. However, once COVID-19 hit, they quickly shifted focus to maritime with remote health applications to stay relevant. Within 8 weeks, they were able to test consumer uptake for the application and expand aggressively through partnerships from there.

Through the entire process of identifying traction with your customers, ensure you follow a framework such as the AARRR.

Infrastructure support is required to perform pivots. Even though I have ordered consumer behaviour ahead of infrastructure, consumer behaviour metrics are often lagging indicators of traction. By contrast, infrastructure assessment has to lead the decision of pivoting. If you are planning to focus on another industry, check to see if you have the necessary infrastructure support. Infrastructure support might have to be reviewed across policy, technology, skills and investments.

If you are in a highly regulated market and planning a pivot, consult with your regulatory body to ensure there are no red flags. Just because your previous product was fine from a regulatory perspective does not mean your new one will be. The regulatory policy can also help accelerate product expansion. If you are pivoting, you should assess if the regulators have any rails that you can use to accelerate product traction.

Technology infrastructure will have to be identified before you decide your pivot. For instance, if your product relies on mobile internet and if your pivot involves focussing on Asia, Africa or Latin America, where internet penetration is low, you might have to go back to the drawing board. You will have to discover the parts of these regions where internet penetration is higher and slowly expand as mobile internet becomes the norm in other areas.

Many entrepreneurs and firms I know have described expanding or moving to a market with a different cultural and infrastructure setup as ‘starting a new company’. Study the skills infrastructure when you are moving into a new industry or market. If your product needs specialist knowledge, such as a PhD in life sciences or quantum computing, you might have to identify ways of acquiring and integrating that talent into your organisation before deciding on the pivot.

Finally, you will need to understand the appetite and maturity of your investor ecosystem towards your new direction of travel. If you are in London, you wouldn't have to think twice about making a pivot into fintech. If you are in Switzerland, you are well supported by an amazing network of investors and policy ecosystem for a pivot into a Blockchain-based use case. If you are in the Bay Area, you will be just fine as long as you have a mask for the smoke and the virus.

A business model will also need to be checked to ensure the pivot is successfully complete. A good look at your competitors and understanding what has worked and not worked for them would help. If you already had a working business model before deciding to pivot, you might want to test that out first.

Remember, a pivot doesn't have to be about reinventing the wheel across the board. The more you can reuse what you already have, the better it is. However, please test every aspect of what you already have without assuming everything will work in the pivoted world because it worked before the pivot.

Preserve the Soul

One thing you want to preserve through the pivot is the culture of the firm and the values that it has been built on. The firm's values must remain in addition to its foundations. To a firm culture is like the steel rods that hold the structure of a building together. Pivoting your business can be compared to changing the layout of the rooms, getting new floors, remodelling your kitchen or adding a conservatory. You still need to have both the foundation and the structural strength intact.

Let us look at a technology startup building a product to serve farmers in emerging markets. You are most likely going to have a strong social impact angle to your business model, but, more important, it would be ingrained in the firm's culture. If you are pivoting and your new focus area is all about making money without a strong social impact dimension to the business, you would struggle to stay passionate about the new direction.

On a similar note, if you have been an organisation with a strong growth mindset in a B2C space and you have pivoted to become an SaaS organisation for large enterprise clients, you might struggle to cope with the change. Therefore, the cultural elements of the firm have to be tapped into through the pivot.

If you see there is a mismatch between the culture of the firm and the new direction, work with your management team to identify ways of tapping into the culture of the firm. If you don't see any ways of doing this in the new direction, identify ways of first pivoting the culture of the firm, or rethink the direction of the pivot.

Although you need to keep tabs on the cultural alignment, you also need to check if your core team is passionate about the new direction of travel. If you have ensured value alignment, that should largely take care of the passion dimension too. However, if you have specialists on your team who have come on board because of your previous proposition, and that has changed, it might be necessary to ensure that they are equally passionate about the new direction.

In summary, start with confirming that ‘if’ the current direction of the firm has become irrelevant to customer metrics. Once you have decided to pivot, understand the landscape of operation and ensure there is enough infrastructure support in the direction of travel. Review business model options and make sure they are in line with the values of the firm. Start testing consumer behaviour while making sure that the culture of the firm is aligned with the new direction of travel. Keep testing until you hit gold.

Continue Experimentation

A pivot is not a new solution; it is a new direction. The ruthlessness in coming up with hypotheses for traction of your products, and testing them continuously in a feedback loop, has to remain. There is no dodging that process. However, with the lean and mean base you created early in the crisis, it might buy you some time and allows you to get creative in the new direction. You will be less worried about the time pressures that fast-depleting cash flows will bring.

Therefore, set up a data-driven engine that will keep testing market traction as the firm navigates its way through the crisis. A continuous data collection process will ensure you will make the necessary adjustments and course corrections required to adapt to the market shifts that keep happening around you.

As described in Chapter 5, you'll want to tap into market and consumer behaviour after you pivot. But you should also focus on how consumer values are evolving through the crisis. As we saw through the financial crisis of 2008 and the COVID-19 crisis, consumer behaviours are often driven by shifts in values. Values might be driven by a sense of security or the lack of it, a sense of fear or just the arrival of a digital generation wanting to transact over the internet.

As Brad Feld mentions, a CEO's role can also be defined as ‘chief experimentation officer’. Create the culture of data-driven culture in the organisation to ensure you are on top of major trends and market movements.

Let us now look at what key elements can help you build an organisation that would have a high chance of survival during a crisis.

Build for a Crisis

Over the last four chapters, we have discussed how first-order optimisation can be done to create room for the survival of the firm. We then followed it up with second-order optimisation, in which we saw the three dimensions to look at: consumer behaviour, infrastructure and business models. In this chapter, we cover how pivots work and your considerations before and after the decision to pivot has been made.

The third-order optimisation is not just about identifying what you need to survive through the crisis, nor it is just about pivot. It is also about looking at ways that will make you more crisis ready. Remember, every crisis is different. You can be culturally and operationally prepared, but it is not possible to predict the market shifts that a crisis can create.

You need to make realignments as you go through a crisis depending on how the market shifts affect your firm. However, cultural and operational readiness should make that process easier. During our interviews with the VC community and startup founders, one comment we continuously heard was, ‘Good startups are built for a crisis’. That explains why the survivors of a crisis often become great organisations.

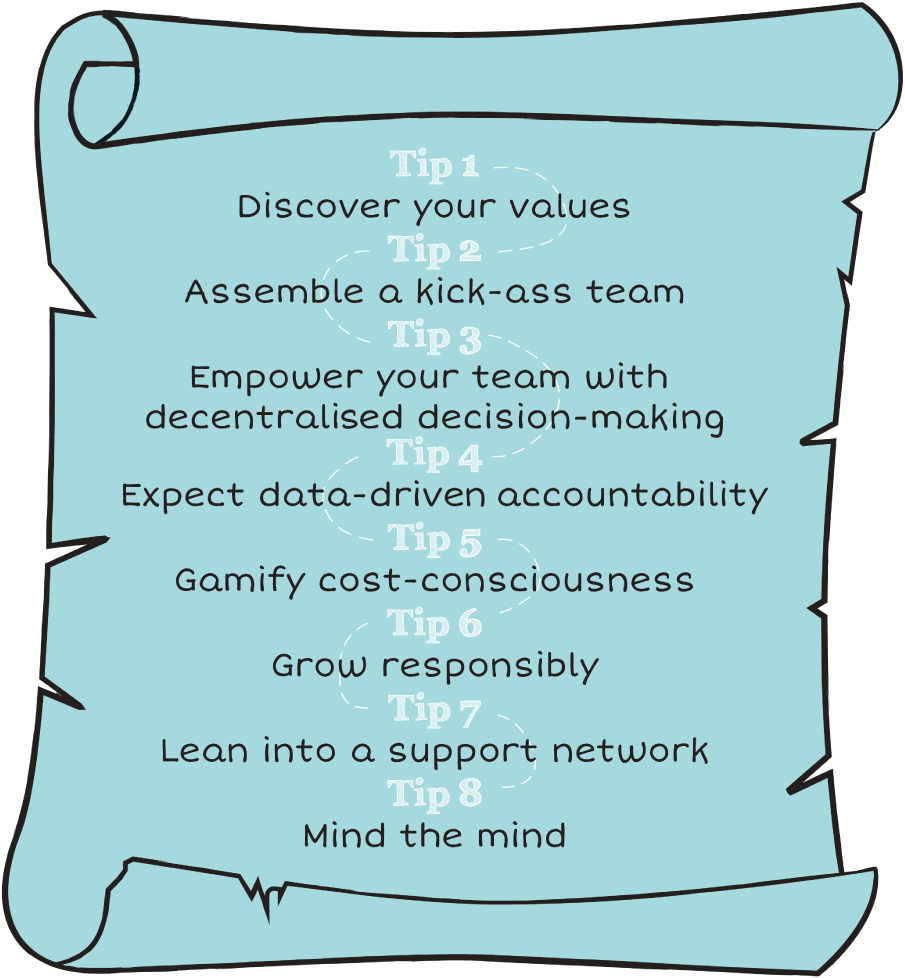

Here are a few tips that will make an organisation more resilient. I call them tips deliberately because there is no such thing as a recession-proof strategy. You can only be more prepared, but be ready to be surprised when the crash comes. These are some of the best practices that you can put into business-as-usual mode at your firm to help you weather a crisis.

Tip 1: Values Make or Break Firms

As a startup, you have to be clear about the value system your firm will be built on. Values are often not discussed when you are a small team working out of a coworking space or a garage. But as you start growing it must be clear where you will compromise and where you won’t as the founding members of the organisation. As discussed previously in this chapter, a good understanding and articulation of your values will help you make better decisions during tough times.

I find many entrepreneurs very clear about their vision for their organisation. But when you ask them what values they want to stick to, they often don't have an answer. Therefore, when they explore business opportunities or business models that could potentially conflict with their values or vision, they struggle to stay on course. Therefore, it would help to define values that you can't compromise on so that it is clear to your investors, board and team.

As much as it sounds like b-school bull, values are what help you define the rest of this list. If your vision, strategy and execution are in stark contrast to what your values are, you will struggle to carry on when times get tough. A clear definition of the firm's culture can help ensure that the values are stuck to. To get the right organisational behaviour you need the right culture evangelised across the firm. As Ben Horowitz suggested, sometimes creating a ‘shocking rule’ can help with setting the right culture, such as these examples:

- Amazon – If the feature doesn't improve the metric (product KPI), the entire feature must be rolled back. This would give you a chill if you were a product manager at Amazon.

- Gmail – Every interaction should be faster than 100 milliseconds. Google apparently loses $4 million of revenues for every millisecond delay.1

- VMWare – Partnerships should always be 51:49, and the partners should always be better off.

Each of these rules reflects not just values and the culture within these firms but also how operationally and strategically aligned their organisations are to their values. But remember, if you are setting rules because your team is doing the exact opposite, assess if the goals you have set for your team are in stark contrast to your values.

A little personal story to help with this point, and it is not to talk about my benevolence. A few weeks back, I was driving my daughter to school. We were extremely delayed due to an accident on the road. The scheduled drop was at 8:35 am, and I was still a mile away at 9:00 am. I had informed the school that she would arrive late. Yet, when I saw an old couple trying to cross the road at a point where they shouldn't be trying to, I stopped for them.

There would have been a few parents in their cars fuming at me for doing so. Yet, I was happy to let the couple take their time. I was willing to compromise on the time of the school drop for my daughter, I was willing to let a few cars honk at me or stay furious but wanted to let the old couple cross the road. This applies in an organisation set-up, too. If your team knows what rules they or their organisation can break, what rules they can bend, what rules they can't even think of compromising, it will clearly tell them what the firm's values are.

Are you asking for high-quality code while setting extremely challenging timelines? What does your team perceive as the organisational values? Getting there on time, getting there with very few bugs or getting there with bugs that doesn't affect value delivered to customers? All these have different cultural approaches, operational processes and hence perceived values. You must set your rules in line with what you believe are the firm's values. It will also help your team decide what rules they can break and what they can't.

Tip 2: It's the Team, Idiot

If there is only one thing that you want to do to keep you going in good and bad times, it is getting the right team in place. There is enough and more written about how you can hire a stellar team and keep doing it time and time again. There are a few things you will want to consider as you build your team. When you found a firm, you are most likely to lean on people you know quite well as the first few members. That is understandable because you want people you know will stick with you during thick and thin.

The weight on familiarity should start going down as you start expanding your team though. Weight on similarity must also go down as you grow your team. Avoid the temptation to hire people who are like you. Look at what you lack and hire people who bring that. If you are an aggressive go-getter, look for some thinkers for your team and vice versa. If the entire team leaps and then looks, it is not going to help during difficult times.

It's hard not to talk about diversity when I talk about the team. Diversity is not a vanity metric that you create for PR purposes. It is not something you should consider to be politically right either. Running a business involves making decisions across different levels in the organisation on a regular basis. You need people with different exposures, backgrounds, mindsets and risk appetites to make optimal decisions.

Although diversity could be considered a vanity metric, inclusion is definitely not. You might have a well-diversified team from age, gender and race perspective. But if you do not create a platform that allows people to chip in with their ideas and make decisions that are driven from these ideas on pure merit, diversity is meaningless.

As discussed in Chapter 4, the COVID-19 crisis has shown that countries led by female politicians have managed better than those led by men. Research by Utah State University of Fortune 500 firms showed that women and men of colour are chosen to lead firms in trouble. That is partly because they had to take on riskier roles throughout their career to get the recognition they deserved. Therefore, they have a higher chance of turning things around for the firm. There is enough evidence to show that diversity can be a differentiating factor in a technology startup.2

Tip 3: Decentralising Decision-Making

During the COVID-19 crisis, many organisations had to quickly adjust to the remote working model. The ones that have really succeeded in staying operational while still keeping their culture intact are the ones that have managed to create leaders across different levels in the firm. If you have created an organisation that understands its core values and goals, it will be capable of making decisions without the founders necessarily being part of it.

Effective decentralisation of decision-making in the organisation can be the litmus test of how well it has kept its DNA intact. Founders and the management team should be able to see that decisions being made without them involved are similar to those that are made when they are involved.

This does not mean that the founding team is not involved in key decisions made by product managers. For instance, since the Blockchain age began, decentralisation has often been misunderstood as a precursor to anarchy. That is not what decentralisation decision-making is about. It is about knowing what the values of the firm are and being able to make quick decisions. But it is also knowing when to reach out to the management and create transparency at the right levels.

The Japanese technique of Nemawashi, in which there needs to be consensus across the board before moving forward with a decision, might be seen as the antithesis of what decentralised decision-making stands for. When the organisation can execute this principle successfully, it can stay nimble and move fast during a crisis.

Tip 4: Data-Driven Accountability

The process of creating leaders across the firm can be quite empowering for the team. At the same time, it can sometimes start creating hierarchies within the organisation. To ensure that decisions are in line with the expectations of the management team and the direction of the firm, decision-makers in the organisation must feel accountable. Accountability can be created by evangelising a data-driven culture.

If a product team is rolling out new feature, decisions about the roll-out must be data-driven. If there has been a personnel decision on hiring a few team members or reshuffling a product team composition, then that must be clearly communicated and justified with data. Therefore, it goes without saying that any strategic decisions on the go-to-market, product pricing or pipeline management will need to be data-driven. That creates objectivity and makes decentralisation easier.

The challenge to this particular element is, what should you do if a decision must be made without enough data points? That is often the challenge in a fast-changing world, because some decisions might have to be made on a hunch. But two aspects to consider are when there are no data and you want to move forward so you are still in the process of experimentation. Then you might want to call it a hypothesis rather than a decision, create the right level of visibility in the organisation and move forward with that.

Remember, if you are at a crossroads and are asked to make a decision, and if you do not have data to justify a course of action, you just have to keep moving forward in one direction with your eyes wide open and ears to the ground. As long as the organisation is aware that you are in a mode of experimentation, it is fair enough.

Tip 5: Embracing Cost Consciousness

In Chapter 4 we discussed the process of cost-cutting and achieving cost efficiencies during a crisis. In order for decisions to be made quickly during crunch times, the organisation needs to have a cost-conscious culture. This must not be confused with cost efficiency. If you are an organisation that is experimenting with your customer base or going full-on with a growth strategy, you will likely have a high-cost base and that's okay.

Cost consciousness means that the organisation understands where the cash is being deployed aggressively and where optimisation is possible at any point in time. This must be the case at all levels of the organisation. Be it the management team looking to expand into a new market, a product manager looking to procure expensive infrastructure or an engineer looking for a subscription the company might not necessarily need – all stakeholders must understand the impact of these costs even though they might not necessarily refrain from spending the money.

As a cost-conscious organisation you will devise strategies to keep your fixed costs low and your contribution margins positive. This will help you stay efficient from a cost perspective. A consistent reporting mechanism on costs will also help understand the viability of product lines. If cost centres seem to be adding too much burden, consider turning them into profit centres as Amazon did with AWS for instance. In essence, staying cost conscious is not just for operational excellence; it provides strategic optionality, and in times of crisis, this optionality dictates survivability.

Tip 6: Growing Responsibly

This is my pet peeve with VC-backed firms across the world. Achieving growth on steroids and going for a winner-takes-all approach has definitely done wonders to the technology industry since the new millennium. However, it might not be the right thing for customers in some scenarios. For instance, if you are a technology-driven lending platform, following predatory lending practices to acquire customers might not be sustainable.

Growth that doesn't keep customers' welfare and values at heart won't last. It can be slapped with regulatory fines in some industries or take a huge reputational hit in others. The other aspect of growing responsibly is testing the viability of business models. As a startup in early, venture or growth stages, unless you are raising funds through crowdfunding, you are largely raising capital from qualified investors. Even with crowdfunding, there are certain regulatory hurdles that will ensure investors have an understanding of your business before they invest.

When you decide to go public through an IPO, you will be taking capital from retail investors who might not have the same level of understanding or expertise in assessing if you are running a viable business or not. Therefore, it might be in everyone's interest to ensure that the business model is scalable and viable before an IPO at least.

Ideally, you would want to check for business viability pretty early on in the firm's life cycle. But it must be the responsibility of the management team and the board to ensure that the business is profitable before it goes public. You would assume regulatory and reputational risks if you fail to demonstrate viability.

Proving business viability early on will help if growth stalls or falls during a crisis. You can go back to basics and still find your way through tough times.

Tip 7: Tapping into a Support Network

As discussed in Chapter 3, a support network can go a long way in helping you through a crisis. Remember that all of us need help to get there. Support networks can be a group of entrepreneurs you reach out to as a sounding board, a mentor network or just your own investors and board members. It is useful to also be close to your innovation ecosystem, which includes investment hubs, incubation and accelerator programmes, corporate innovation, and even government-supported innovation programmes.

All these can come in handy during a crisis if you have the right relationships. The relationship might be built through a rigid time timetable involves socialising through events and informal meetings. Alternatively, it could be accomplished by just building rapport with key stakeholders through social media channels. Consistent engagement with them through content creation can build familiarity and credibility in a relatively short period of time. A support network can help you with keeping your ears to the ground during a crisis to understand market shifts, investor appetite and the general direction of the industry you are operating in.

A support network must not be mistaken for an advisory pool or a bunch of people you lean on emotionally or to discuss ideas alone. It can also be viewed as the system that you plug yourself (and the firm) into so that it is in the best interest of this system to ensure you are successful. An admit into VC cohort or a cheque from Sequoia or A16Z or a huge corporate VC arm can fall into this category of plugging yourself into the right system. These organisations have the might to change the fate of their startups by virtue of their network.

Tip 8: Mind the Mind

I wanted to keep the best for last. Mental health is very critical for entrepreneurs. That has been the biggest takeaway for me through the process of writing this book, the research we have done and the interviews we conducted. You don't expect Usain Bolt to set a world record without a personal trainer. Entrepreneurs are like top sportspeople who have to be able to hit peak performance at crucial times. Their decision-making capabilities must be quick, unbiased, instinctive and as data-driven as possible. Their communication needs to be effective in the context of where it is delivered.

A healthy mind can make better decisions, be more empathetic and help connect with its team and stakeholders more effectively. Innovation communities across the world are still not matured enough that entrepreneurs can discuss and understand mental health issues openly. However, this must be something that you should sensitise your board and your investors to quite early in the firm's life cycle.

An empathetic culture within the firm amongst employees can help with mental health challenges. During my discussion with Onfido's CEO, Husayn Kassai, he mentioned that they had a mental health programme as part of their benefits package for their employees and it was the most used and popular benefit. We need more startups to be part of mental health discussions in a supportive environment.

Engaging in team activities to create an informal environment and build rapport can help ease those discussions, too. When team members find it difficult or delicate to discuss issues openly, create a private channel or a programme that they can be part of within or outside the organisation. On top of the support with mental health, as your startup becomes cash-rich, explore performance coaching sessions for at least the founding team members.

With that, we come to the end of the third-order optimisation process. Although the topic of pivoting is largely applicable to firms that have become irrelevant, strategies suggested for pivoting can be used on a regular basis. Adopting practices that give you the capabilities to be nimble during a market crash can be used by all firms.

Figure 8.1 shows a sketch note summarising this chapter.

FIGURE 8.1 Chapter Eight Sketch

Conclusion

We have now reached the conclusion of the strategic pillar of this book. We went through the first- and second-order optimisation of your business in the previous four chapters. This chapter covered the third-order optimisation process. The first part of the third-order optimisation was about identifying if you needed a pivot.

Your customer traction can be measured using the pirate metrics or the AARRR framework. These metrics enable you to break down the process of acquiring, engaging and retaining customers. Referrals help with achieving growth and revenues are really the proof of the pudding, demonstrating that you have a viable business model that can scale.

When the pirate metrics start to look bad, and you haven't been able to turn them around after a couple of iterations, it's time to look to get your thinking hat on. Gather data to understand why the metrics have started to look bad. If it points to fundamental market shifts, changing customer behaviours and values, consider a pivot.

We then discussed what pivots could look like. Pivots do not necessarily mean reinventing the wheel or redoing everything from scratch. Pivots can be a change in strategy, revenue model, target consumer segment, target market or just the underlying technology.

We also looked at factors to protect through a pivot. If something has worked well for your firm before the pivot, try to keep that aspect intact. If you have been successful in building a sales culture, protect that through the crisis. You must also ensure that the pivot is in alignment with the values of the firm and passions of the core team members. A pivot might not work if the team is not passionate about the new direction of the business or product.

Beyond pivoting, we also looked at best practices that entrepreneurs should consider to prepare them for a crisis. Remember, it is not a major crisis if it doesn't have the surprise factor. As mentioned in previous chapters, the surprise often hurts you more than the market shifts themselves. However, looking after the firm's values and building a good team that understands the culture can help stabilise the firm faster during a crisis.

The operational aspects of the firm need consistent attention as well. A cost-conscious team will be able to get to a lean and mean base faster during a crisis. Business viability must be continuously tested to make sure customers and investors are protected. A viable business can keep its head above water for longer during difficult times.

Finally, we touched on the importance of the mind. A healthy mind makes better and quicker decisions during a crisis. Entrepreneurs must be at the top of their game in problem-solving mode, and mental health is critical to achieving that. Every startup should prioritise mental health as a key success criterion for its teams to look after. Investors and board members must be inculcated with a culture of embracing mental health issues.

We have now covered the three main pillars of the book: an understanding of the macro environment in Chapters 1 and 2, mental health in Chapter 3 and the three orders of strategy optimisation in Chapters 4 to 8. In the next chapter, we will bring it all together with mind maps and flowcharts summarising key concepts and takeaways from this book.

Notes

- 1 Source: https://akfpartners.com/growth-blog/what-is-latency#bs-example-navbar-collapse-1:~:text=How%20fast%20is%20100ms%3F%20Paul%20Buchheit,the%20threshold%20%E2%80%9Cwhere%20interactions%20feel%20instantaneous.%E2%80%9D

- 2 https://www.usu.edu/today/story/studies-show-women-amp-minority-leaders-have-shortertenures-tenuous-support