CHAPTER 4

The Surgical Strike

I must be cruel only to be kind.

— William Shakespeare, Hamlet

Introduction

I landed in the UK in autumn 2005 for an assignment with GE Capital. Over the course of the next 15 years, I have had the opportunity of living and working in the great city of London. I have worked in teams that had Europeans, Russians, Americans, Indians and Australians. Save New York, it is hard to see the diversity and variety we get to see in London anywhere else in the world.

I know several of my British friends have not just been tolerant but also proud of the diverse nature of the workplace and social set-up in and around this great city. However, all that changed in 2016. As the referendum tipped in favour of Brexit and populist regimes thrived across the globe, we felt the world was moving towards a new normal. The markets in Europe took a hit at the news of Brexit.

What followed was nothing short of a political disaster in the UK for three long years. The UK was in a political turmoil that led to economic uncertainty. Several overseas investor friends I spoke to, between 2016 and 2020, agreed that the fundamentals of the UK economy were strong but market sentiment was weak. We needed a decisive leader to get the country out of this crisis. We got it with Boris Johnson, who was precisely that.

I didn't vote for the conservatives nor for a Boris leadership during the 2019 elections. However, I was glad when he was voted to lead the country out of the Brexit deadlock. I am not a Boris supporter, but he was perhaps the best person for the time and he got us through the first major hurdle of the Brexit nightmare.

This is precisely what we need in business leaders during a crisis. You may be right, you may be wrong, but you must be decisive. If you wait for data points to show up to validate your decisions, it might be too late. The same can be said of Jacinda Ardern, the prime minister of New Zealand, and Angela Merkel of Germany in the way they have led their countries through the COVID-19 crisis.

These leaders have been quite clear about their priorities in protecting lives over economies and enforcing lockdowns and initiating economic packages to support households and businesses. However, my favourite in the list of leaders who stood out during this crisis has been K. K. Shailaja, the health minister of the State of Kerala in India.

Kerala is a state in South India with 35 million people. Under the leadership of Shailaja, the state had the first COVID rapid response meeting as early as 24 January 2020. The 14 districts of the state had medical officers assigned to oversee on-the-ground activities. The public was quickly educated on the measures against the virus. A strict regime came into place to track and trace infected persons and treat them appropriately. At the time of writing this chapter, the state had about 1,200 cases and nine deaths.

To put this into perspective, Kerala's population density is 2,200 people per square mile. New Zealand has 46 and Germany 623 people living in a square mile. At the time of writing this chapter, Germany had about 184,000 infected people and New Zealand had about 1,500 cases. A comparison between Kerala and the other states in India will bring to light the effectiveness of crisis management in the state. By comparison, states such as Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu (my home state) have recorded 12 and 8 times the number of infected people, respectively.

Through the course of the COVID crisis, all of us have seen enough such numbers. Therefore, I apologise for bombarding you with more of them. However, the way the state of Kerala and Shailaja have handled the crisis is a case study for the top b-schools and businesses of the world to document and learn from.

The idea of walking you through good crisis management stories across the world is to help you with the rest of the chapter. Crisis management requires both sides of our brains working closely with each other. That is particularly true for this chapter because you might have to plan and execute a surgical strike in the interest of your business. The decision-making process has to be cold and objective, but the execution must be humane.

The models defined in this chapter and the next few chapters are not prescriptive. They are meant to help you think through your business in the context of a crisis and arrive at a solution. Market crises do not homogeneously affect all businesses in a bad way. Businesses can benefit from a crisis, some of them see a temporary slowdown, while others take a very bad hit. Let us delve into this a little bit before getting into the planning and execution of remedial actions for the business.

The Startup Bell Curve

Most experienced investors and entrepreneurs who have seen a crisis or two would tell you that quick and decisive action, early in a crisis, helps in a big way. There are also other schools of thought around scenario planning and taking action dependent on how the crisis unravels. Nevertheless, all of them would agree that inaction and keeping the business going in business-as-usual mode is very rarely the solution.

Before planning a course of action, it might help to understand the effect recessions can have on start-ups. That would help position yourself through the rest of the book and identify logical next steps.

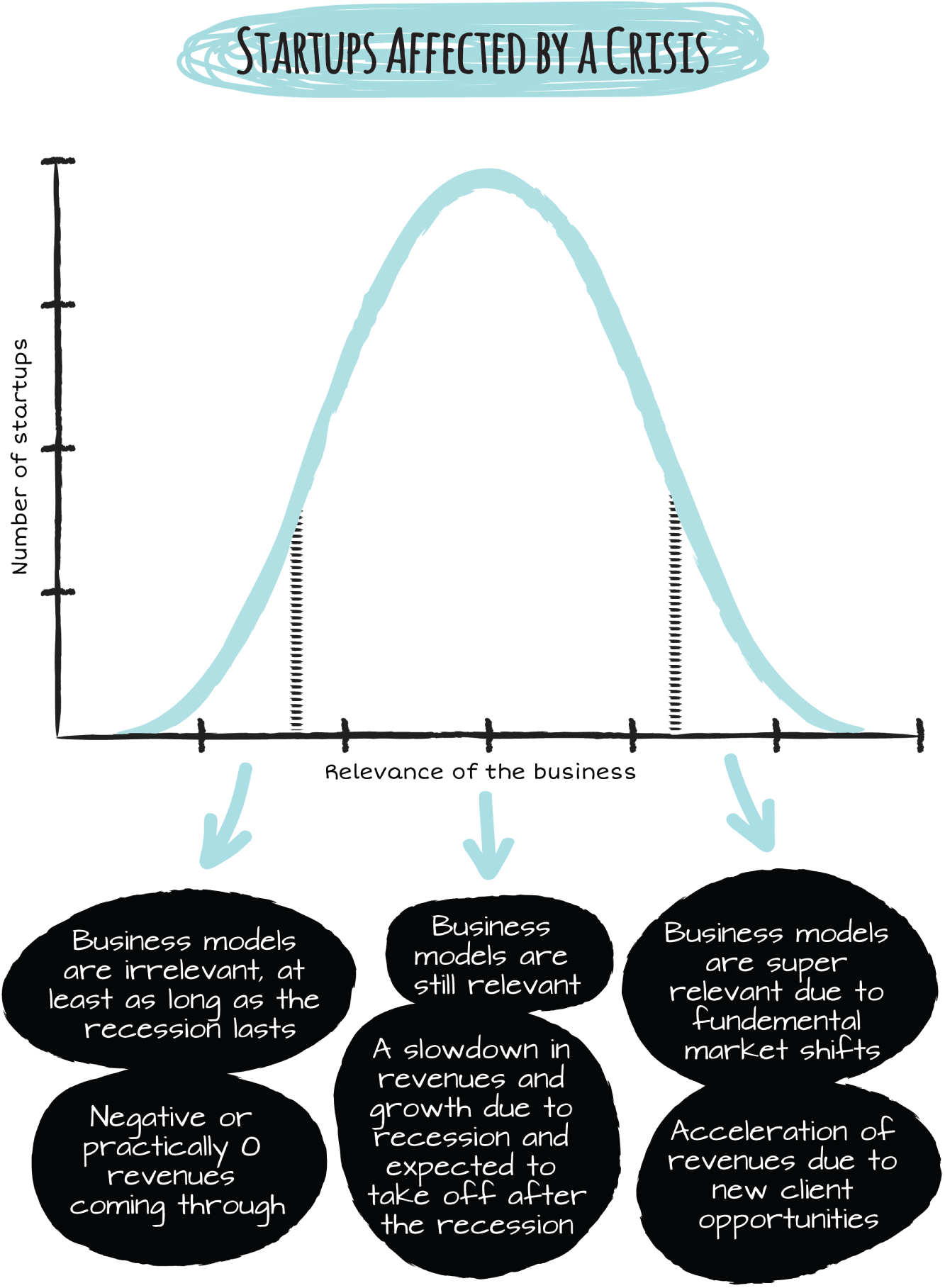

Recessions have different ways of affecting start-ups depending on their sectors of focus and business models. There are three key categories that startups hit by recessions fall under.

- Business models that have become irrelevant or even start seeing negative revenues

- Slowdown of revenues while business models remain relevant

- Acceleration of revenues with business models taking off due to sudden changes in market fundamentals

For instance, some travel start-ups went into a negative revenue state during the COVID crisis. Loyalty startups focussing on restaurants, pubs and coffee shops were terribly hit by the crisis as their revenues plunged due to almost no transactions happening at these retail outlets. They might not have become completely irrelevant as businesses, but they might have to evaluate their market relevance until the crisis comes to a close.

Another small percentage of businesses would emerge as a silver lining to the crisis and see an acceleration of their business models. For instance, many education technology (EdTech) and communication companies saw their revenues take off as soon as the COVID crisis hit. Zoom saw a 169% increase in revenues, beating their annual forecast by Q2 2020.

If you imagined the distribution of startups hit by a crisis as a bell curve, the two categories of irrelevant and super-relevant businesses form the tail of the curve (see Figure 4.1). The majority of start-ups fall somewhere in between the two tails of the bell curve. These start-ups in the centre of the distribution typically see a fall in growth and revenues, but they would still be relevant. Sales cycles might be longer, but clients would still be interested yet cautious.

In the next section we look at a three-phased approach to dealing with a crisis. The first-order optimisation stage is applicable to all three types of firms in the bell curve, because it helps them stay lean and mean. The second-order optimisation is more applicable for the firms that need to reevaluate their strategic response in a crisis. The third optimisation applies to firms that need to examine the crisis to stay relevant and reinvent themselves. We discuss third-order optimisation and pivoting in Chapter 8. Let us now look at the 3D plan of action.

FIGURE 4.1 Crisis Bell Curve

A 3D Plan of Action

We will need to take a three-pronged approach to respond to a crisis. The initial step, called first order optimisation, involves taking tactical measures to preserve the firm through the crisis. We then move on to the second-order planning and execution, where we look at strategic ways of tweaking and course correcting the business. Last, the third-order planning involves data collection, planning, realignment and, if needed, pivoting the business to position it for what lies ahead.

Survive: First-Order Optimisation

This is the first step in the planning and execution process and involves the immediate preparation of the business to sustain the challenges of a recession. As you switch into preservation mode for the business, it is not just about cost-cutting recklessly; understanding the purpose of the business, your vision for the business and what got you there is also necessary. The data collection we discussed in Chapter 3 will come in handy during this phase.

Once you have a clear view of what you see as the core of your business, you then need to plan ways to make progress with that, while cutting costs on non-core activities and markets. The first-order plan is typically executed within the initial days of the crisis. You will also need a clearly defined communication architecture for smooth execution of management decisions. These are the focus areas for this chapter.

Normalise: Second-Order Optimisation

Once you have met the immediate and high-priority needs of the business, understood the core focus areas and adjusted the cost structures, the next step is to focus on the strategy for the medium term. The first-order planning would have given you a lot more freedom and latitude in planning and executing the next steps. The cash flow pressures should be alleviated and the leadership team should have the ability to define a context of operations for their focus areas of the business.

As a result, the second-order optimisation involves understanding the following changes in light of a market driven by the crisis:

- Change in infrastructure

- Change in customer behaviour

- Change in the relevance of business models

It is important to understand these fundamental changes to plan a course of action for the business. For instance, after the 2008 crisis customers were so unhappy with Wall Street banks that they wanted innovative ways of interfacing with financial services. That led to fintech companies.

On a similar note, after the dot-com bubble the internet acted as the infrastructure layer to support the growth of social media and internet-based companies such as Amazon, Facebook and Alibaba. The payments infrastructure developed by governments and regulators in countries such as Singapore and India allowed digital payments to grow quickly as soon as the COVID crisis hit.

With shifts in customer behaviour and infrastructure, the second-order planning and execution become critical for the strategic direction of the firm. We will focus on this in the next few chapters. Second-order optimisation is more strategic and will take longer to execute than first-order planning. As a result, you will need more data points to support your decisions, unlike first-order optimisation. The second-order plan of action will need a few weeks of research and discussions before being put in place.

Thrive: Third-Order Optimisation

The third-order plan is important because a crisis often throws a curveball to disrupt existing markets and opens new opportunities. Third-order optimisation is about looking beyond for a new normal. It is an exercise in exploring unknown unknowns. It is also important to take away some habits that you need to stick to during good times that you learnt during a crisis.

This step might not be relevant for all businesses in a crisis. If you are running a business that has come to a grinding halt due to a market disruption, this is certainly an exercise worth going through. This is also a stage where you know your existing business model is almost obsolete and must identify ways of reinventing yourself.

This process is often easier for early-stage start-ups than for matured firms. It can be an extremely time-consuming and high-risk exercise in larger businesses. However, it has been done in the past even within big businesses. Therefore, with the right leadership, vision, research and planning, it is possible to execute this step effectively.

Now that we have briefly touched on all three stages of optimisation, it's time to deep dive into first-order planning and execution.

First-Order Optimisation

When the house is on fire, you do not look to save your wallpaper. The focus will be on protecting lives, then essentials, and finally the structural elements of the house to keep life moving without any major obstacles. That is precisely what you should focus on when a crisis hits your business. In Chapter 2, you performed data collection to understand where your business was. That information, combined with the diagnostics that you will perform in this chapter, will help you with decisions later in this chapter.

If I must simplify the outcome, you need to protect your core business and people while preserving cash. If your business has become irrelevant due to the crisis, then focus on cash flow preservation for now while you reinvent yourself.

One assumption of this chapter is that you have identified and achieved business continuity wherever you can. During the first two weeks of lockdown, several businesses accelerated the process of getting their employees to work from home. When this is possible, a business can continue, and you can start getting back to the first-order optimisation process after that.

Cashflow planning and taking measures to extend your runway in an optimal fashion is one of the primary objectives of this chapter. Let us now look at why cashflow management is so critical.

CashFlow Is Oxygen

A few days back I was having a cynical discussion with a VC friend. During good times we prioritise growth over profitability, and during bad times we focus on cash flow over profitability. Is profitability out of fashion then? Both of us knew that businesses that fancied their chance during a crisis will need to go back to the first principles of doing business. One of the basic tenets of doing business is testing and ensuring the viability of the business model and the ability to turn profits. Yet, it was an interesting question to reflect on.

A more pertinent question, at a time when a business is trying to keep its head above water, is how to ensure there is enough cash flow to keep the business running. That's a tricky question because it is hard to time the bottom of a crisis. Therefore, calculating the amount of cash flow that would take you safely to the end of the crisis is hard. Remember, a crisis typically lasts longer than we anticipate. Therefore, the first thing to do is to create enough cash flow for as long as you possibly can.

You might be a business with revenues of £500,000 coming into the bank account in three months, but that is not going to pay your employees' salaries at the end of this month. Revenues are an indication of the clients' appetite for your products and services. Cashflow, however, is an indication of the health of liquidity and the operational agility of your business. It is also worth noting that during a crisis you might see a collapse in revenues. Even contractual revenues might not show up, if your clients want to renegotiate terms.

Therefore, it is essential to have a cashflow projection modelled even during good times to ensure you are always financially provided for. There shouldn't be any liquidity mismatch between short-term outgoing and long-term incoming cashflow. If there are any mismatches, suitable financing options must be planned in order to fill the gaps in cash flows. Alternatively, the flow of outgoing or incoming cash must be tweaked to ensure there are no nasty surprises.

This exercise becomes more critical during times of crisis. As mentioned, keep in mind that a crisis always lasts longer than we expect. Therefore, it is essential to plan a cut down of outgoing cash as aggressively as possible. Let us now discuss performing some diagnostics on your business.

Soul Searching

This process is about performing diagnostics across different aspects of your business to identify core and non-core areas. If you had spotted structural issues with the economy even before the crisis hit, you might have performed some data collection as discussed in Chapter 2. That data would help make quick decisions. If you had not done that, it is still not too late to perform some diagnostics on your business.

Running diagnostics to execute the first-order plan should keep more than cost-cutting in mind, such as the following:

- Understanding the core areas of your business

- Understanding core markets that you want to serve

- Spotting opportunities to improve cost structures

- Identifying product areas that are directly relevant to core business and revenues

- Identifying suppliers and vendors for cost optimisation and renegotiations

- Identifying areas of marketing that are still relevant

- Identifying critical team members to execute your strategy through the crisis

Despite it being the last item on this list, team is, in fact, the most important of all. People are your biggest asset. Treat your people well, and they will take care of your business.

While running through the diagnostics (see Figure 4.2), it is important to keep the objective in mind. Be critical, but recognise biases that surface during the diagnostic process.

FIGURE 4.2 Diagnosis

What's the Heart of Your Business? The diagnostics process is to ensure you do not make any haphazard decisions and have a clear understanding of why you are making certain decisions. The first step in doing so is to zoom in on what the core of your business is. That will need to be aligned with your/your board's vision for the business.

If you enjoyed an increase in revenues in your core business lines as a result of the crisis, then you are amongst the lucky minority. The crisis moved the market in your favour and accelerated product relevance. But if you are in the majority, who saw a fall in revenues and felt cash flow pressures due to the crisis, then determining your core business is important.

Ask yourself why you started the business and what the problem you were trying to solve was. Every founding team has a vision that it wants to hold on to despite all odds. This is the vision that helps you persist during the worst days of your start-up journey. Understanding that will help you identify the part of your business you must protect.

It is quite possible that what you consider as the core business is not bringing you revenues yet. It might be that you have found an ancillary revenue opportunity to fund your core business. In that case, it becomes even more critical that you hold on to the revenue opportunities to protect your core business in the long run.

VC investors will cringe at this advice, because focus is everything in a VC investor’s eyes. If you have a core business, focussing on it ruthlessly until you find ‘product-market fit’ and growing it from that point forward is the VC style of going about it. I agree with that approach if your start-up can scale only through VC funding and growth-based strategies.

One of my portfolio firms Gyana managed to sell their non-core product Neera through the COVID crisis to protect their core product Vayu, a NoCode data science platform. NoCode data science platforms allow users to perform analysis using algorithms without having to write a line of code. This is typically what VC-funded businesses do. They know their core focus and double down on it in spite of the crisis.

In stark contrast, when I spoke to David Brear, the CEO of 11FS, I received a slightly different viewpoint. 11FS is a digital transformation challenger consultancy that grew at an amazing pace from 2017. In 2019 they established 11FS Foundry with a vision to build a core banking platform for the digital era.

In David's view, although the services business had yielded the majority of his revenues in the short- and medium-term, 11FS Foundry is where he sees the long-term business opportunity. Therefore, he felt it was essential to keep the lights on for both these business lines despite the challenges that the crisis had thrown at them. I personally believe that the digital wave that the COVID crisis triggered might in all probability bring more opportunities for 11FS Foundry in the short term as well.

You get the picture though. This is a time where you need to preserve your core business, and it begins with knowing what it is, and more importantly, why it is. It might well be that your core business model is completely irrelevant during the crisis, as we discussed earlier in this chapter. In that case, you might still want to cut costs and go through the third-order planning process to identify next steps. More on that in future chapters.

Where Are You Relevant? In your quest to run a tight ship through the crisis, one of the questions you need to ask yourself is in what markets your products and services are the most relevant. Let’s say you have done well in London with your product and have recently rolled it out in Manchester. As part of the optimisation process, it is worth evaluating if you want to keep investing in Manchester, a nascent market for your product.

On the same note, if you have several product lines, it is essential to understand which ones are worth pursuing. Contribution margin* is a tool that can help you understand which markets and products are viable during a crisis.

If you have scaled across several markets, there are going to be a few markets where your product has a lot more traction than others. This is typically measured by the contribution margin. This tool shows if your revenues in specific markets are high enough to pay off your variable and fixed costs. During times of crisis, this metric becomes important to help focus on the right things.

Let's say that you have decided to cut down variable costs associated with selling a product; you will still be incurring fixed costs such as office space and management salaries. Your contribution margin must be high enough to cover these fixed costs. Otherwise, you will be loss making.

Going back to identifying your core markets and products: even in good times, you must know the markets that have healthy contribution margins. An ideal contribution margin will be close to 100%, and most healthy businesses have contribution margins ranging between 60% to 100%. This will also help identify the markets and products you could double down on during a crisis and perhaps stop expanding into markets where your contribution margins are not high enough. The same methodology can be used to assess where a product is worth pursuing during such times.

Is Your Cost Structure Optimal? Following on from the analysis of the core focus areas for the business, products and markets, let us look at the importance of an optimal cost structure. In all the interviews I have done for the book, one consistent theme that has emerged is that businesses should increase and accelerate incoming cash and decrease and slow down outgoing cash. It sounds pretty simple and straightforward.

But what if your cost structure doesn't lend itself to making quick nimble changes to manage cashflows? What if your business model is more value-driven rather than cost-driven? It might be worth understanding the differences between value-driven and cash-driven business models.

Businesses that rely on low-cost structures, process automation and outsourcing are typically cost-driven. Businesses are value-driven when their core proposition relies on personalised services. For instance, luxury products and services can fall under this category. In a value-driven business, it might not necessarily be possible to apply some of the commonly known cost-cutting measures, such as automation or outsourcing.

Evaluating cost structure during the first-order optimisation process is meant to be performed ideally within the first two weeks of entering into a crisis. It might not be possible to revamp your entire cost structure for the first-order planning and execution exercise. However, it is worth understanding the importance of having efficient cost structures at all times, not just during a crisis.

One tool to stay on top of costs efficiently is the operating leverage of your business. Generally, operating leverage is lower when your fixed costs are lower. When a business has a high operating leverage, it helps during sales growth to increase profitability. This is because the incremental cost of sale is minimal. However, a high fixed-cost base makes them less agile during periods of declining sales.

The reverse is also true. When firms have a low fixed-cost base, they have lower operating leverage. However, with a high variable-cost base, as sales happen, the cost of sales also increases. Therefore, their profitability is flatter than in a high fixed-cost base business. But they are also relatively stable during times of falling sales, because their cost base reduces with reducing sales.

During my discussion with Simba Rusike, the CFO of Assurance IQ, he mentioned how critical the cost structure was for the success of the firm. Assurance IQ was acquired by Prudential for $3.8 billion after three years of operation. Their cost structure and data science capabilities made them the growth engine that Prudential was keen to tap into.

After the COVID crisis hit us, I spoke to several CEOs across the world to understand how they dealt with the crisis. I have seen two broad types of firm deal with the crisis well. One set had efficient cost structures and effectively low fixed costs. Therefore, they were able to quickly respond by reducing costs and keeping the business afloat. The other set continually tested the viability of their business as they expanded; therefore, these businesses have been able to get to profitability if they wanted to.

Both these aspects are not mutually exclusive. They highlight that going back to first principles of doing business can help preserve your firm during tough times. It involves keeping costs low and managing higher profit margins. Keeping it that simple would help a good proportion of businesses face a crisis. Yet, this might not be easily achievable if your business model relies on growth first.

For instance, if you are creating a marketplace that needs onboarding critical mass of the supply and demand side to demonstrate network effect, then growth typically must come first. That is a proper VC approach, and unless you have already raised some funds just before the crisis or demonstrated network effect to excite your investors, you might struggle to raise further funding to keep the business afloat.

Also, as a VC-backed firm, your fixed costs might already be quite low. It is worth understanding the ratios that you need to track to ensure you are cost efficient. It might be as simple as the cost of acquisition (CAC) per customer and lifetime value (LTV) of customers. A ratio between the two can be compared with your peers.

More unconventional ratios/metrics can be between investments/revenues or (sales + marketing costs)/revenues and even the time it takes from the point of incurring marketing costs to the point of receiving the revenues. Some of these metrics will need to be specific to the business models you have and even the industries that you operate in. In essence, identifying the metrics that help you manage the cost efficiency of your business is critical.

Let us now look at the process of scenario planning that you should go through to understand the cash flow needs of the firm.

Scenario Planning

Once you have completed the diagnostics process, you will need to create scenarios and plan how you would cope through the crisis. It is quite difficult to spot a crisis coming at you, but it is equally hard to know how long it will last. Therefore, look at the cash flow position of the firm and understand your runway.

If it is March 2020 and you expect that the crisis will last until June 2021, try to model scenarios that would take you to December 2021. Model scenarios for when the crisis comes to an end sooner or later. Study the nature of the crisis and learn from history. For instance, if a pandemic caused the crisis, it might last 18 to 24 months. If it is a structural crisis that caused a recession, it might take a few quarters to recover.

In all these different scenarios model the following variables:

- Cash flows

- Revenues

- Churn

- Investment milestones

Based on the current performance of your firm and how the initial days of the crisis affected your business, project these numbers. Be conservative. Reach an agreement with your board and management team on all the assumptions behind these scenarios across these variables. Once you have agreed on the assumptions, based on what you and your key stakeholders feel, agree on which scenario is most likely to materialise.

That should tell you how much cash you need to preserve or raise to ensure the business is protected through the crisis. This will then need to be reviewed through the lens of the diagnostics process you went through in the previous section. Bring the scenarios and the diagnostics together to see where the alignments and misalignments are. If your cost-cutting measures are perfectly aligned, and seem viable with your vision of the business, then it's a relatively easier decision.

In the following section we have put together a simple framework to help you with your decision-making.

The Soul versus Value Quadrant

Objective and ruthless decision-making is essential if you want to get through a market slowdown. Remember, you are going through this process because you are not one of the fortunate few whose business has taken off after the crisis hit. The decision-making process on where you will save costs and how, will need to be made across two key dimensions:

- How core is the business/product/market to your firm?

- How much value is it currently bringing to the firm?

The simple quadrant in Figure 4.3 should help you with the prioritisation process.

This figure will help you assess how core a product or a business line is to your firm versus how much value it is bringing to the table. Take a short- or medium-term view on the value aspect because you are in a recession and are looking at ways to preserve cash. The framework uses a generic term value here, but that can be replaced by revenues, cash flows, growth or even brand equity in some instances.

Let me briefly go through the quadrant now using product lines for ease of discussion and to get the easy decisions out of the way first.

High Value/Core: When a product line is core to your business and is a high-value proposition, press the pedal on it. Be laser-focussed on delivering that through the recession. This is the easiest decision quadrant in the framework.

FIGURE 4.3 Soul versus Value Quadrant

Low Value/Non-Core: When a product line is non-core to your business and is still a low value proposition, kill it. It might be a difficult decision if you see value coming in the near future; however, this is not a time for speculation or wishful thinking. Be ruthless.

High Value/Non-Core: This is the most interesting part of the quadrant, and I have seen different approaches to this. My instant reaction is to sell that product line to improve cash flow. This might give you a couple of quarters of runway, which could be massively helpful to focus on your core business. I mentioned my portfolio firm Gyana selling their non-core product line to preserve and grow their core product line through the crisis. However, Gyana had the luxury of cash flow as they had closed a funding round just before COVID hit and managed their cash flows quite well in response to the crisis.

However, there are other approaches to deal with this particular quadrant. You might choose to preserve the non-core product line in light of the growth or revenues you are seeing from it. You might end up enhancing this product line through the recession as you get more customer traction. As a result, this might end up becoming core over a period of time, which means you have effectively embraced this as key to your business. In all these instances, the key outcome must be cash flow preservation.

An Amazing Turnaround: FrontM

Focussing on the non-core product line can sometimes feel like selling your soul to the devil. I have seen many CEOs crib about that in the past and many run out of motivation for the business as a result. However, the risk of not exploiting the revenue opportunity from the non-core business is that the business might cease to exist. If you choose to go with the non-core product line, you must agree on checkpoints with the board to assess when there will be life pumped into the core product lines that you really believe in.

And so you dangle a carrot (the hope of returning to the heart of your business) to keep you focussed on the non-core areas of the business. You might want to see your non-core product line as a means to an end. As these product lines make more revenues, you increase the chance of achieving your vision for your core product line.

Low Value/Core: This is an easy decision in the context of the crisis but emotionally hard for entrepreneurs. You might want to park your passions for the time being and focus on revenue generation before you get back to the heart and soul of your business. You might also take a less binary approach if you are not that cash-strapped to keep the core areas of the business alive through the crisis. However, that needs to be clearly discussed and agreed with the board to ensure there are no cash flow concerns.

Cold Decisions, Humane Execution

We have understood the core focus of the business across markets and products. We have discussed the importance of keeping an optimal cost structure. We went through a framework to help determine what stays and what goes. Now you need to focus on applying this strategic thinking to cost decisions on the ground. Although I recommend making more aggressive cost-cutting than your cashflows indicate, you might have reasons to go softer. However, the earlier and the larger the cost savings are during a crisis, the better it is for the business.

Decision-making must be objective if you are looking to get to a good position to take on the second-order optimisation stage. However, despite an objective and unemotional decision-making process, the communication and the execution of it must be humane. The CEO of the firm plays an important role in developing the communication architecture of the firm during times of crisis.

Surgical strike of cost-cutting measures can be ‘sandwiched’ between humane communication. Firstly, manage expectations with clear messaging. Then, follow up with the cost-cutting measures. Lastly, communicate to boost the teams’ morale. Communication that precedes the cost-cutting measures will need to be about setting expectations on the status quo, which is to soften the blow. The communication post-execution will need to be about improving morale and providing context to the team.

Let us look at the communication architecture options that you can deploy through the first-order optimisation process.

Communication Architecture

The first-order optimisation is the point at which effective communication architecture helps with organisational morale. It is also essential to have the right narrative across all your key stakeholders. If you are a young start-up with agile communication set up like daily standups, you might want to have short bursts of information delivered to your people regularly. However, if you are a larger scale-up with a couple of hundred employees, you might adopt more formal communication methods.

Authenticity: The Team In either case, the right amount of communication, at the right time, with authentic and genuine information must be provided to keep the organisation's morale up. Overfeeding employees with information can be a distraction and not communicating regularly might result in a nervous workforce. There might have to be a mix of formal and informal modes of communication depending on the mood of the organisation, too.

In starting a quick, objective and targeted cost-cutting activity, information flow can be unidirectional. Management can communicate the impact of the crisis on the firm and measures you are taking to combat the crisis to the employees. Therefore, when it comes to making tough decisions, it might not come as too much of a surprise to your people and doesn't lead to too many questions.

Transparency: Investors Consider your investors when you plan your communication architecture for the first-order optimisation process. Investors need to understand your plans for the business in the short- and medium-term. As the crisis throws new challenges, you must proactively reach out to investors and update them on the challenges you face, the opportunities ahead and your decisions on how you want to steer the business forward.

It is important to communicate your strategies to your investors. It is perhaps more important to communicate bad news to them promptly during these times. Transparency is the best way to ensure you receive their support and advise. Do not wait for your monthly or quarterly board or investor update. Investors are generally happy to take time, listen to you and offer advice and help for the journey you are embarking on.

Optimism: Clients and Suppliers With clients and suppliers, take a more tactful approach to communicating. Showing vulnerability and telling clients how bad your cashflow position is, might not be the best way to hold on to them. Be a little bit more upbeat with clients without falsifying information. With these two sets of stakeholders, get the best person in your team to work with you in engaging with them regularly. You typically have certain members of your team who have the best-trusted relationships with these external stakeholders. Get them involved in communication.

A detailed stakeholder map and a corresponding communication technique and tone can help bring clarity. On each of those legs of communication you might have to draw out a schedule and assign it to the best person to send that out. Get a group in charge of communications within and outside the organisation and make sure they are in line with the tone and semantics agreed on for the narrative with the stakeholder.

Empathetic Optimism: Social Media You also might want to decide if you want to engage on social media and what the tone of engagement would be. During a crisis such as COVID, even if your business is performing well due to the rise of digitalisation, you might want to play it down and show some empathy to the affected. However, you should also demonstrate that you are contributing to society and to your clients (if you are), in all possible ways. A lack of empathy on social media can come back to hurt your reputation.

Once you have understood your organisation and agreed on a frequency and mode of communication through the first-order optimisation process, it's time to evaluate the commercial relationships that you have with your partners, clients and vendors. The following sections will detail the steps to take.

Clients: Increase Incoming The first step is to see if you can increase cash flows in the form of revenues. Be mindful of the focus areas for the business while negotiating with your clients. Keep clients who are in your focus areas closer to you at this time. Also focus your conversations with clients on the following avenues.

Expansion: Discuss if clients have more opportunities within their business lines for your products. You should do this even during normal business periods. However, if you have a good relationship with a client, he or she might either extend your business or top up with a new product or service. This can be extremely beneficial during tough times.

If you are running a consumer business, look at how you can tap better into your existing user base without having to spend too much on acquisition costs.

Quicker Payments: Renegotiate payment terms to see if you can receive some cash (receivables) earlier than previously agreed. This can help alleviate some of the immediate cash flow challenges that you might face. Remember, every little action helps.

Pricing Models: Renegotiate pricing models, especially if the revenues are purely transaction or usage based. The number of transactions or the use of your platform might fall drastically through a crisis. If clients are paying you a transaction commission, then you might see that trending to zero.

Hedge your risks by renegotiating the pricing model with your clients. Ask for a minimum fixed payment that the client could make in exchange for lower transaction or usage fees. This would mean you will receive a small revenue even if there were no transactions on your platform.

Pricing model negotiations should be based on the churn modelling exercise you did through scenario planning. If you do not have scenario models with the best, neutral and worst-case scenarios of customer churn, you might not be able to perform pricing changes that are contextual and meaningful.

Suppliers and Vendors: Decrease Outgoing Be objective in your assessment of vendors and suppliers. If a supplier or vendor does not fall in your area of focus that you identified in the diagnostics process, add them to the list of terminations. Be benevolent with these stakeholders by agreeing on a gradual ramp-down of the engagement, rather than immediate termination. However, this book is not about running charities, so let me cut to the chase. If you do not need a vendor in your core areas of business, you shouldn't let them burden your cash flows.

Also consider discussing a new payment structure with the vendors and suppliers you badly need to keep the business going. Instead of a monthly payment plan, negotiate a quarterly or a half-yearly payment plan if this is acceptable. However, in dire times, I would terminate non-core vendors and suppliers aggressively to ensure those who really matter are kept happy.

It is in your best interest to keep the suppliers that matter to the running of your business paid on time as they would be under cash flow pressures as well. Therefore, keep the money flowing to those who matter to your business during this time. This might sound cruel, but a crisis is a time when you are looking to survive: it is ok to be cold in decision-making.

Once you have made decisions about your vendors and suppliers, about who will or will not be continued, figure out how to deliver the news. The COVID crisis has seen some mindless firing of people and suppliers through very short and rude Zoom calls. That attitude will come back to hurt you if you are a small or mid-sized player, and cause you reputational damage if you are a big player. If you can't hold on to a supplier, at least hold on to their goodwill.

It is now time to evaluate cost-cutting options internally.

The Firm: Align Culture In Chapter 2, we did an evaluation of where the firm was and who was critical to the operational capabilities of the firm. That information will help us with evaluating cost-cutting options within the firm.

Following are some obvious choices of cost-cutting during dire times. But the objective is perhaps more than that. When it comes to internal costs, the outcome should be about creating a cost-conscious culture within the firm. As the leader, it is important to show the team that you are taking serious cost-cutting measures. This can quickly lead to an avalanche of voluntary cost-saving suggestions from the team.

Consider brainstorming with the team on how you can cut costs creatively. The best idea wins a reward! Gamifying cost-cutting can yield excellent results both culturally and monetarily. Yet, as the leader of the firm, you should be leading this from the front. If you preach without practising, your team will take it only as seriously as you do. Let us now look at some cost-cutting options.

Office Space: In a world where the workforce is becoming truly global, office rent is one of the areas I would look to cut costs. In the post-COVID world, I wouldn't be surprised if offices are used more like a conference area for critical meetings, board discussions and workshops. I truly hope that organisations will see the benefits of letting staff members work from home. This cost-saving is an obvious choice.

Management Salaries: If you have a management team and a board that is getting paid way above the rest of the team, it is worth revisiting their compensation structures. This is a time when the management teams should step up to such initiatives and offer to give up a slice of their short-term compensation in the interest of the business.

Marketing: We have identified core business lines, products and markets through the diagnostics process. It's worth going through a detailed breakdown of the costs associated with these non-core business lines, products and markets. If you have been spending on marketing the non-core parts of your business, you might want to cut those down. Often, it might not make sense to spend on marketing certain products that are irrelevant during a crisis and they might be low-hanging fruit too. In other scenarios, just as a crisis kicks off, markets might pivot towards a product that no longer needs too much marketing.

For instance, pharmatech platforms that deliver pharmaceuticals to your doorstep grew without any marketing spend even during the initial days of the crisis. However, they are in a minority of businesses that benefitted from the crisis. If you are not one of the fortunate ones, it might still make sense to ramp down on marketing spend to understand where the market is heading as the crisis unravels. This will help position your firm accordingly through the second-order optimisation process we will describe in future chapters.

Operations and Technology: If you have an outsourced operational process that is no longer relevant or core to your first-order optimisation process, that should go, or at least pause. While making operational and technology cost-cutting, it is critical to assess if you are adding any major operational risks to the firm. Make sure the board and the management team are aware of the risks and are happy to assume the risks of the operations function that is going to be paused or culled.

Supply chains that are serving the non-core areas of your business can be areas of saving as well. In essence, follow the diagnostics data and make quick and easy decisions. Technology costs could come down if your infrastructure and costs associated with it fall as product usage goes down. Your technology team might have costs like cloud subscriptions that they may not necessarily need. Look for areas where small-value, large-volume cost can be cut.

Team: Handle with Care Of all the decisions you might have to make, letting your people go will be the hardest. Before resorting to redundancy, consider a few creative options:

- See if the management team have taken a salary cut.

- See if the senior management team is willing to take a salary cut. The alternative could be that they might lose a good part of their team.

- See if you can roll out a wrapper percentage cut in people's pay instead of laying off employees.

- Evaluate government support such as furlough pay.

If you have done all that and still are falling short of the cost-cutting you need to do, as agreed by the board, then look to lay off employees. In places such as Silicon Valley, letting go of people is not considered a major issue. Both employees and employers understand the handshake mechanism and are always cognisant of the implications. However, in other parts of the world, laying off employees can come with reputational and legal implications.

In Chapter 3 we looked at identifying the poor performers and the outliers in the organisation. Poor performers are those who are working on critical projects, loyal to the firm but lack the quality expected by the organisation. Outliers are those who are good quality, but lack the passion for the business and are expected to leave the firm anyway.

It is worth evaluating your pool of employees again in the light of the crisis and the focus areas drafted for the firm. Employees who are most vulnerable in this process are the low performers in the non-core areas of the business. This is followed by the low performers in the core areas of business and then the outliers. Before you make the final list of employees you would let go, consider talking to the outliers on their willingness to leave the organisation voluntarily.

If you had adopted an effective communication methodology, employees must already have a sense of what the management considers to be the focus areas for the short term. If you have a clear performance management process in place, they will also know where their performance ranked across their business unit or organisation. Therefore, a layoff might not come as a surprise.

As you are announcing the layoffs pretty early in the crisis, the market still might be hiring for talent. Therefore, there is a good chance that the employees you choose to let go could find a job quite quickly before the crisis takes off. Sachin Jaiswal at Niki.AI, a firm where Ratan Tata is an investor, had to let go of a third of their workforce due to the COVID crisis. However, he mentioned that more than 50% of those people got placed within the following four weeks.

The decision to let go of people, and who, has to be scientific, methodical and quick. However, the delivery of the news has to be as humane as possible. Try to deliver the news within a day, if possible, without staggering the layoffs over a period of time. This helps the survivors to take relief in the fact that the worst is behind them and they have to get going with the job in hand. If the crisis deepens and you have to make further cuts in a few months, at least they will understand that it was beyond the firm's control.

The delivery of bad news should be as personalised as possible. Try to split the delivery of the news to your employees across the management team and senior managers. Provide a forum for exceptional circumstances to be discussed as a quick follow-up. Always try and help these employees to find a job within firms you have relationships with. Suppliers, vendors, clients and peer groups of start-ups can all be excellent places to suggest. However, also beware of competitors who might want your employees to learn about the operational details of your firm.

There are different ways firms approach cost savings with their workforce. Some take a blanket salary cut approach, some lay off in one swing, and some lay off in iterations. However, the objective behind it is to create a runway for as long as possible with the least amount of operational and reputational risk. The art is to ensure you hurt as few people and families as possible in the process. Let us now go through a few experiences of CEOs across the world and their thoughts on the first-order optimisation process.

What Next?

That concludes the first-order optimisation process. You have understood the soul of your firm, you have looked at scenarios of cost cutting and executed measures in line with one of the scenarios. Keep taking stock on the health of the business and cash flows until the business landscape gets better.

The first-order optimisation should just give you the breathing space to steer the ship through the storm. In the process of cutting down outgoing cash and increasing the incoming cash, you have created the much-needed buffer time as you and your management team plan and execute more strategic steps. A crisis can shut some doors and open new ones, effectively changing the market landscape itself.

Therefore, you need to be in a state where you are worrying less about the immediate term and start focussing on the medium-term strategy of the firm. Some market trends become clear a few weeks into a crisis. The COVID crisis opened up opportunities for digital collaboration, health care, edtech and even cybersecurity. However, this wasn't obvious as soon as the crisis hit, because the whole world was just focussing on dealing with the pain.

A few weeks into the crisis, we were able to see these trends emerge. We are still not done with the COVID crisis at the time of writing this chapter. We are most certainly not done with understanding major market shifts and drifts due to this crisis. However, businesses that entered the crisis and stayed relevant despite a fall in revenues will have enough data points to strategise next steps. We will cover that in the second-order optimisation process.

Conclusion

Time and time again, the one input I have received from CEOs and VC investors who have sailed through a crisis is this:

‘Act swiftly and decisively. Cut more aggressively than you can project’.

The earlier you spot the crisis and act, the better it is for all stakeholders involved. The team will have less cash flow pressure and clearer heads to execute more strategic measures. Let me quickly summarise where we have got to so far.

In previous chapters, we discussed the macro view of capital markets and went through the crises we have seen since the 1980s. We touched on some data collection on your business that could help when you see an overheated market or structural economic challenges emerging.

However, all that preparation might not be enough to predict that a crisis is coming, the time of it or help you respond to it. For instance, although there were sporadic signs of an overheated market before 2020, the COVID crisis was largely an event-driven crisis. Therefore, if you had been prepared for a crisis caused by structural issues in the economy, you might not have been entirely prepared for the speed at which we were hit by this event-driven crisis.

FIGURE 4.4 Chapter Four

In any case, once a crisis is here, the first step is to ensure that you are punching from a stable footing. The leaders of the organisation must be clear about their abilities and passion to drive the business forward. They should be able to establish a support system that they can rely on through the tough times.

That readiness will then prepare them for what we discussed in this chapter. Firms get hit in different ways by a crisis. Some of them become completely irrelevant, some get a big boost; and the majority stay relevant with a fall in growth and revenues. For all of them, the first step is to preserve the heart and soul of the organisation. See Figure 4.4 to capture the gist of this chapter.

Once leaders have identified the soul of their firm, it is then about managing cashflows to ensure the soul of the firm is preserved through the crisis. This can be possible by a good understanding of cost structures and focus on the business across products and markets. We discussed all of that at length in this chapter.

Then you need to execute a well-thought-through cash flow management strategy. Increase short-term cash by renegotiating with clients, tweaking pricing models and accelerating receivables. If you have suppliers and vendors looking for payments from you, negotiate on terms that will ease your cash flow. Be objective about your suppliers and vendors.

Finally, we talked about the people who make the firm what it is. We did touch on assessing the performance of your employees during the data collection described in Chapter 2. Many organisations do this as an annual or half-yearly exercise. These data, combined with the focus areas for the business as identified by the first-order optimisation, should help you make quick personnel decisions.

We also touched on the importance of communication architecture through these difficult times. A CEO should find ways not just to communicate but also to connect to employees with authenticity. That will reduce nervousness, breed trust and help you deliver bad news when you need to do so.

Once you have done all this within a span of a couple of weeks of the crisis taking shape, you should be in a good position to plan the second-order optimisation phase to reposition your firm. That's what we focus on in the next three chapters of this book.