CHAPTER 1

Even Shit Floats in High Tide

All that glisters is not gold,

Often have you heard that told:

Many a man his life hath sold

But my outside to behold.

Gilded [tombs] do worms enfold.

— William Shakespeare, The Merchant of Venice

Introduction

Five years back, I was pitching to an investor for my venture capital (VC) fund. I showcased the startups I had invested in and explained how well they had all performed since the investment. He was quiet for a few seconds and responded,

“Even shit floats in high tide.”

He had observed that all our investments were made during bull markets. He continued to push me onto my backfoot, saying our investments should withstand a crisis to really stand apart. I was shaken by his comment because he was right. I remember telling myself, ‘This is it, I've lost it'.

All the investments I showcased to him had happened in 2014–2015 when the market was pretty healthy. He had seen through my sales exercise. Somehow, miraculously, I won him over and he became my cornerstone investor. One thing led to another and we later partnered to set up Green Shores Capital. Together, we have so far invested in more than 15 startups, and many more individually. However, the philosophy has often been about assessing how well a startup would perform at times of stress.

In 2019–2020, we have closely followed trends about the rise of investments into late-stage startups, fall in VC investments in Asia, the rise of corporate VC and the rise, and subsequent struggles, of the Softbank Vision Fund. These were macro trends that we have been keeping tabs on. We also witnessed a slowdown in funding for early-stage startups during 2019. However, as the COVID-19 crisis has unfolded, we've seen activity fall off a cliff.

We reached out to all our investee companies, discussed their plans and suggested ways they could navigate the crisis. We made several observations during those conversations. There were differences in the way each of them approached the crisis. We saw nervousness, resolve, confusion, hope and, in a few cases, excitement.

Everyone entered the same crisis, yet the way companies have reacted to the crisis varied remarkably. This is largely because of how they had set themselves up for crisis. That led us to think through the ‘Why?’ behind the way our investees have responded. During our due diligence process at the time of investing in these companies, we analysed their preparedness for a crisis. But very few will disagree if I said, ‘You cannot be completely prepared for a crisis’.

In this book, Max and I will go through the journey of a startup getting into a crisis, living through that crisis and emerging out of it. In the process, we will bring together insights from across the world – from VCs, startup CEOs, central bankers and ecosystem stakeholders. We have chosen a few case studies that we will pick best practices from and highlight them throughout the book.

In this chapter, we will discuss why it is important to understand that the bull (market) has been running for too long. This comes from regularly keeping tabs on the key markets across the world, understanding how the macros affect the startup ecosystem, assessing the potential scenarios that could unravel and staying sufficiently nimble to respond effectively.

If you are an entrepreneur, you might want to ask, ‘Why should I be interested in all that? I have enough on my plate with just building my product and selling it’. Remember, successful entrepreneurs are generally compensated so well, not just because they have built and sold a product. They equip themselves with information to navigate their firms through both market highs and lows. Now, let us turn to why the macroeconomy matters and how an understanding of that helps an entrepreneur to make informed decisions.

The Macros Matter

Be it in fitness or finance, the macros matter. Let us first start with the scenario we were in before the COVID crisis hit. A raging bull market that just couldn't be stopped. The Brexit vote was finally behind us and market sentiment had improved. Europe saw a huge influx of institutional capital and there were VC funds with a lot of dry powder*.

We knew things were unsustainably rosy and on the surface we celebrated every single win: new client contracts, investments at crazy valuations, expensive hires, glossy PR and the list goes on. The Burn rate* for businesses was so ridiculously high that we asked ourselves, ‘What do they spend so much money on every month?’; however, we ignored them because times were good. I wouldn't go as far as claiming there was a systemic bubble forming before the COVID crisis hit, but there were sporadic signs of an overheated market.

Startups claimed crazy valuations during investment rounds. I remember sitting at a pitching lunch session at Mayfair in London. There were about 15 family office and VC investors sitting around the table, and there was one firm pitching to us through the expensive lunch that was served. The firm pitched for a £12 million funding, had an artificial intelligence (AI) component that was revenue-generating and were building a Blockchain component to enrich their product offering.

They had a burn rate of £1 million per month, had raised £9 million only a few months ago and had made about £300K in revenues over the previous 12 months. They weren't fundraising to grow their clientele on an already revenue-generating AI component; instead, they chose to invest into a potential add-on using Blockchain. The £12 million, they claimed, would help the whole product to be rolled out in 9 months' time, after which they were planning to fundraise again. They were valuing their firm at £72 million.

Pitches like these make me cringe. However, they did win some investors from that pitch. Those were times when investors had a lot of capital. When we see consistent deployments of capital into low-quality propositions such as the one I described, it is often a sign that people do not know what to do with their money and are desperate to deploy. That leads to bad investment decisions, and when a wave of bad investments collapses at scale globally, it can result in a recession, as it did in 2008.

We saw a bit of that when Softbank Fund I struggled after the WeWork episode and hasn't been able to raise its second fund since. If you are a startup, you could be asking, surely Softbank is a multi-billion-dollar player, and why would it have a capital crunch? Hold on to that question; it will be clear when we discuss the capital pyramid.

During several events, discussions and social media interactions, I have been asked why VC investors don't deploy in certain types of assets or at certain times of business cycles. That is because not all the capital deployed by a VC is from the partners of the firm. There are other investors behind the scenes, called limited partners (LPs), and they can dictate terms. So, the risk appetites of VC investors differ in line with the risk appetites of their LPs.

Therefore, it is critical that entrepreneurs understand the macro variables that could potentially hurt or help their business: events that are not close to their day-to-day reality, such as an interest rate hike or fall, a sovereign default or a large institutional investor failing to raise its second fund. All these have an impact on the innovation community and the flow of capital into startups. A good understanding of these macro events and their potential repercussions help startups and their management team stay prepared for any structural events.

This might not seem as important when the markets are booming, but, much like bad times, good times don't last either. Therefore, it is always prudent to stay on top of macro trends that affect capital flows. Without further ado, we shall dive into the money pyramid that the capital flow is built on.

Capitalism: The Pyramid Scheme

The world of capitalism can be visualised as a money pyramid. It can be imagined as a pyramid that has capital flowing from top to bottom, with a few, mighty firms at the top. As capital flows from one tier of the pyramid to the next, value is added and the organisations in the tier are compensated for the value addition. Let's go through the institutions that make the pyramid work (see Figure 1.1).

Tier 0

Central banks sit at the top, ensuring there is liquidity (money flow) in the system. They are also interested in ensuring that the markets are behaving and consumer appetite is optimal. They keep track of their region's business landscape, trade balance, inflation, consumer spending, foreign direct investments and market sentiment. They have a few tools, such as interest rates and quantitative easing, to manage some of these factors that they continuously track. The amount of liquidity within the pyramid is often influenced by the policies that central banks enforce.

Tier 1

Wall Street banks and large blue-chip firms schematically sit below the central banks on the pyramid. In the context of understanding liquidity in the capital markets, they can be viewed as Tier 1 organisations. They are the means through which capital is distributed across the system. The health of these financial institutions and large corporations often reflects the health of the economy.

On top of facilitating liquidity throughout the pyramid, in recent times these organisations have directly interacted with technology startups through innovation labs, corporate venture funding and joint ventures.

Tier 2

Tier 2 of the pyramid is where institutional investors such as endowments and pension funds operate. This tier receives capital from organisations and their employees who contribute to pensions and endowments. Endowment and pension funds distribute capital to other parts of the system from this level. Based on their risk appetites, they allocate capital across different asset classes from equity, fixed income, real estate and PE.

Tier 3

Tier 3 is what entrepreneurs need to understand closely. This tier of the capital pyramid comprises of the specialist money managers who run niche investment vehicles to address specific categories of investment. They have specialist skills to address an underserved market or find the much-needed alpha for Tier 2 organisations.

FIGURE 1.1 The Money Pyramid

Tier 3 can be categorised as VC and PE organisations that are private market players and hedge funds that invest into public markets. In more recent times we have large corporations setting up their venture investing arm. These are called corporate venture capital (CVC) firms. CVCs are Tier 3 organisations that have been a growing segment of institutional investors since the 2008 crisis.

CVC has been a recent addition to the list of institutional actors in the capital pyramid. CVCs are typically venture arms of big corporations who have allocated funds to invest in startups. When CVCs fund startups, they typically look for two key dimensions. One is the return on investment through appreciation of share value, which is similar to a VC. The second criterion is strategic synergies between a firm and the startup they have invested in. This criterion is a key difference between VCs and CVCs. CVC investors can often take a firm they have invested in to their clients, do joint ventures and, over a period, can acquire them, too. In that sense, CVCs do feel as if they are smarter and more strategic money for startups because they not only help in funding the firm but also could become a client or the distribution.

As a result, as soon as the investment is made, many CVC investors can look to use the product or the services of the startup in their own organisation's business units. It is both capital and client for the startup winning the cheque. However, CVC investors also typically invest slightly later than VC investors do. More on the VC–CVC comparison in Chapter 6.

Tier 4

There is another group of investors in Tier 4: family offices, ultra-high-net-worth individuals (UHNWIs) and high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs). These are typically families, their wealth managers and individuals who have made or inherited millions of dollars and are looking for investment opportunities.

The primary difference between these stakeholders and the institutional investors is that Tier 4 investors have the ability to make investment decisions with less formality. Tier 4 stakeholders can also be convinced quickly because they typically do not have onerous investment processes in place. They are also seen as the least-sophisticated set of investors in the pyramid.

Tier 5

At the bottom of the pyramid are the startups and the small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which are looking up the pyramid for capital to flow down. Despite being categorised as the bottom of the pyramid, SMEs make a big contribution to the health of the economy. As per the UK Small Business Statistics (www.fsb.org.uk/uk-small-business-statistics.html), there were 5.82 million small businesses in the UK that account for half of the turnover in the private sector. They also employed 60% of the UK workforce (16.6 million).

Please note that not all of these SMEs are the technology startups that this book focuses on. The statistics include all small businesses, from a grocery store to a coffee shop.

Often, depending on the maturity of the startup, and the business and market conditions, money can flow directly into them from Tiers 2 or 3 of the pyramid. For ease of understanding the flow of cash in the form of transactions through the economy, you can visualise consumers in this tier of the pyramid, too. However, consumers buy products and services from businesses, and the health of the large corporations in the top tier is often reliant on the buying capacity and appetite of these stakeholders.

Let us now discuss what drives capital flow from or into each of these actors, thus keeping liquidity in the system.

Role of the Central Banks and Regulators

We briefly touched on how central bank policy can affect capital flow across the economy. Central banks and regulators have a pivotal role in driving capital through the pyramids. This, in turn, has an effect on investor appetites and funding for startups. The purpose of central banks is to ensure they maintain a healthy economy through the balancing of essential economic variables. For instance, economic policies can trigger inflation during good times, which in turn can push the central banks to react with interest rate hikes.

However, during previous market downturns and recessions, central banks have employed quantitative easing and interest rate cuts to introduce liquidity into the system. But, too much cheap money can cause a currency market crisis and increase sovereign debt. If a major economy starts accumulating debt, it can potentially lead to their investment grade being cut by rating agencies such as S&P and Moody's.

During a recession, central banks need to pump oxygen into the economy while also making sure they do not risk a rating downgrade. If a country's ratings are cut, it could hurt their ability to borrow money and might also result in foreign direct investments (FDIs) drying up. Central banks have the unenviable job of striking the right balance among all these different variables. From a startup perspective, it is worth understanding how policy could affect FDI inflows, thereby limiting capital available for them to grow.

Let us now look at how central banks and regulators have taken a more proactive role in engaging with the innovation ecosystem. In recent times, some regulators have taken on a more hands-on role to support their innovation ecosystem. Innovation policy from these regulators across the world has had a major impact on the innovation community in the region.

In some countries, such as Singapore and India, the regulators and the government have proactively pioneered the infrastructure required for startups. For instance, the unified payments interface (UPI) developed by the government of India has been the foundational building block for digital payment infrastructure in the country. Fintech firms such as PayTM, PhonePe and global players such as GooglePay and WhatsApp pay have used this infrastructure to accelerate their services to the end customer, thereby triggering the adoption of digital payments in the country.

On a similar note, the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) has paved the way for digital KYC (know your customer) and digital payments for technology firms to leverage. Firms that need to perform KYC on their customers do not have to rely on a repetitive, document-intensive and time-consuming process. They can just reuse the KYC solution that the MAS has facilitated.

Although Asia has taken a more hands-on approach to building its digital infrastructure, Europe had more legacy infrastructure to start with. Therefore, European regulators have been more collaborative with technology startups and provided more of a hand-holding process in guiding innovation in the right direction.

European regulators such as the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) and the European Central Bank (ECB) have facilitated innovation through regulations such as the Payment Services Directive (PSD). That has triggered the application programming interface (API)-driven innovation paradigm called open banking. These regulators have catalysed change through policy making rather than building the necessary infrastructure to lead innovation. The FCA also has a sandbox that works with startups and helps them understand the regulatory implications of the solutions they are working on.

Therefore, regulators can help the innovation ecosystem not just through monetary policies but also through infrastructure support. This is especially critical in emerging markets economies where legacy infrastructure is largely absent. A lack of legacy infrastructure is an opportunity for both regulators and innovators. In developed countries, infrastructure policies can open up opportunities for new players and increase competition.

We will revisit the importance of regulations and infrastructure policy in Chapter 6 in more detail. Let us now look at how the economy behaves during good times.

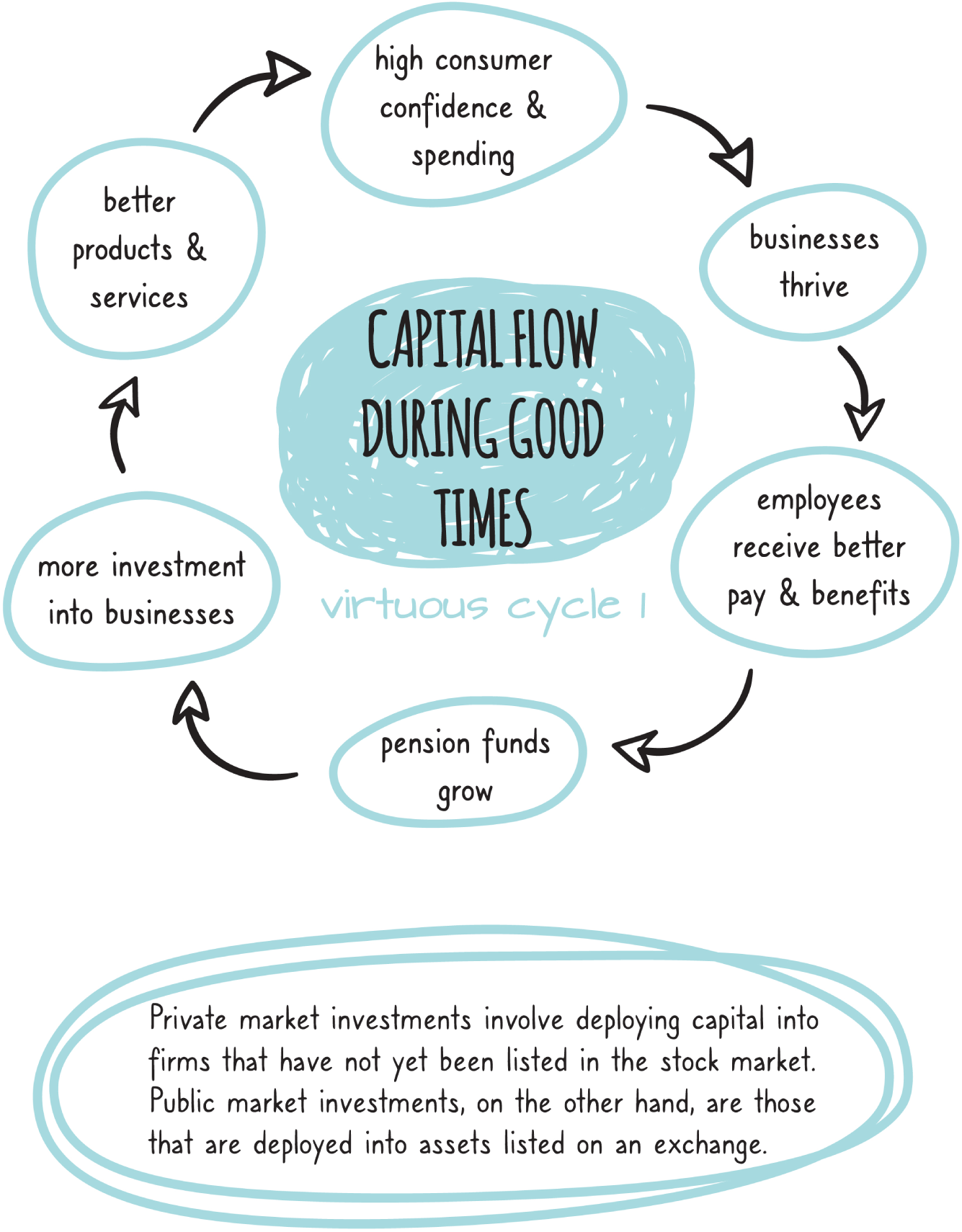

Virtuous Cycles

During good times, the economy sees a flow of capital through transactions that act as the oil and keep the capitalism engine running smoothly. Consumers' appetite is at a high as they are actively buying products and services from large corporations. For the sake of simplifying this process, let us understand that the economy sees transactions happening from the top tier in the pyramid to the bottom tier of startups and small businesses.

Organisations at the top of the pyramid do well, thanks to consumer appetite. Banks see a rise in deposits and credit decisions are typically easier. If you are looking for a mortgage during these times, you are more likely going to be asked fewer questions and require fewer documents. Banks also act as distribution channels of capital to businesses. Therefore, with ample liquidity in the system, businesses are able to access the capital needed to build and expand.

As a result, these are times when large firms are making good revenues, healthy margins and, consequently, expanding operations. They are hiring aggressively and employee salaries, bonuses and pensions are on the rise. This results in the flow of capital into the next tier.

As a result, endowments and pension funds that are Tier 2 institutions have a good influx of capital from these flourishing organisations at the top. Tier 2 institutions are vehicles set up to deploy capital efficiently across a broad range of asset classes. Two such asset groups into which funds are allocated are listed and private equity (PE).

A vast portion of capital from Tier 2 institutions is allocated for public markets. This is deployed into funds that invest in public markets. A part of capital deployed in the public markets will be used to take positions in shares of the firms whose employees contribute back to the pension funds. This creates a virtuous cycle in good times (see Figure 1.2).

A similar cycle can be seen as pension funds invest in private equity and venture capital, which, in turn, invest in startups/businesses. Startups thrive on creating value through innovative services and products, resulting in higher consumer spending, thereby keeping the cash flowing through the system.

The allocation of capital into PEs and VCs increases during low-interest-rate environments as cash gets cheaper. As LPs see yields from traditional investment vehicles and public markets fall, they turn to the riskier asset classes such as PEs and VCs.

It is worth noting that these virtuous cycles become vicious during recessions. As liquidity dries up, all parties stop interacting with each other. As trust in the system goes down, the cost of capital typically increases. There is less motivation for LPs to look at risky asset classes such as PEs and VCs in such a climate. A stock market crash can also create a liquidity crunch that breaks these virtuous cycles. Often, there is a lack of trust between counterparties that do business with each other during a liquidity crunch. It is the role of the central banks to break these vicious cycles and get the virtuous cycles back in motion.

FIGURE 1.2 Capital Flow During Good Times – Virtuous Cycle 1

The capital pyramid has good liquidity during a market boom (see Figure 1.3). Stakeholders at different tiers of the pyramid can access capital with relative ease. Even banks relax their lending rules during this time. As the market rises, it is invariably accompanied by growth in the real estate market. As residential real estate booms, we often see a phenomenon called the wealth effect.

FIGURE 1.3 Capital Flow During Good Times – Virtuous Cycle 2

The Wealth Effect

The Wealth effect is a behavioural economics concept that articulates that consumers spend more as the value of their assets (properties) increases. There is a sense of abundance when property prices increase, which leads them to to their ebullience. This, in turn, brings more transactions, more liquidity and more confidence into the economy, acting as yet another virtuous cycle.

The wealth effect is noticed at different levels in different economies based on homeownership. In the UK, for instance, homeownership is the most prominent form of wealth and a rise in property prices has a higher correlation with a healthy economy. In other economies, such as Germany, where renting is widely preferred, homeownership has a lesser effect on consumer spending.

Therefore, if we must choose one north star key performance indicator (KPI)* for the economy, it should be consumer spending. If consumers keep spending healthily, the economy performs well. The moment consumer spending falls due to a credit crunch, unemployment or other structural issues, the economy goes into recession.

We have looked at ways the economy reinforces itself during a bull market. An understanding of these macroeconomic behaviours is essential for entrepreneurs to plan a course for their businesses. Let us now look at the motivations of the institutions in different tiers of the capital pyramid to understand it better. Let us start with the large corporations at the top.

An Interplay of Incentives

Thanks to the capitalistic society we live in, corporations are mostly interested in increasing short-term shareholder returns. In the process, they look at expanding their top line and bottom line, business lines, products and services, global presence and brand equity. As firms adopt a ‘winner-takes-all’ approach, hiring the right skills becomes crucial. Companies often pay competitive and, at times, predatory salaries to attract and retain talent. This results in better employee salaries and benefits.

Employees in an organisation play two crucial roles related to keeping the capital pyramid efficient. They contribute to pension schemes that will help with their retirement. They also play a critical role as consumers who are getting prosperous along with their organisations through a bull market. It is essential that employment numbers look healthy to keep the market sentiment positive.

As corporations flourish, pension funds receive a healthy amount of capital. These funds look for ways to deploy the capital to ensure their assets under management appreciate. They have their risk appetites and holding periods to adhere to. They deploy capital into the liquid public markets and the illiquid private equity markets. Because private equity investments take longer to make returns, pension funds will have to wait for a few years before they see any meaningful returns.

PE and VC funds deploy their capital into private businesses and startups where the returns can be high, typically above a 25% internal rate of return (IRR). PE and VC investment thesis rely on their portfolio businesses getting them returns that are several times the invested capital. When these funds get it right, such as in the following instances, they make up for the losses from other investments in the portfolio.

As PE and VC firms exit their investments and disburse their returns, they typically charge ‘carry fees’ from their investors or LPs. It is often easily said that PE and VC firms receive capital from their LPs, without highlighting the challenges involved. The usual suspects of the VC world have a track record of investments. As a result, they are often reached out by LPs (endowments, pension funds, fund of funds).

In good times, VC funds have dry powder, which sometimes puts them under deployment pressures from their LPs. LPs have committed capital to the VC funds hoping the VC investors would start deploying their capital. However, there are times when VC investors do not find good enough investment opportunities and are still under pressure to invest.

This sometimes forces VC investors to make a hasty investment decision to keep their LPs happy. VC investors who have capital during bull markets can do that with relative ease. During good times people want to invest actively all through the pyramid. Therefore, as VC investors raise capital, they are also keen to deploy them into startups.

First-time funds typically have a harder time raising funds from LPs. It is often much easier to raise capital for a startup that has a specific business model, a known market, a stellar team and some product–market fit. However, when LPs invest in first-time VC funds, they are relying on a team that could make them huge returns from a blind pool of capital. As an investor, a blind pool of capital can feel more intangible than investing in a startup.

Many of these first-time VC investors focus on early-stage startups due to the limited amount of capital they can raise with their track record (or the lack of it). Often, they have to operate akin to a startup themselves, show progress through deployments and raise funds in parallel. These VC investors often have to wait a few years before they can start showing their portfolio performance and push for bigger funds.

Now that we have discussed the motivations of investors through the pyramid let us take a closer look at interactions between startups and VC funds during a market boom.

Investor Dilemma

A bull market is a time when excitement is everywhere and, even for the analytical investor, mediocre startups might look like excellent investment opportunities. As a result, this is a time when startups can call the shots and be choosy about the investors they take money from.

I was recently in a conversation with a VC friend who is focussed on growth-stage firms. He mentioned that in 2017, he was on a call with a portfolio firm and its potential investor for a subsequent fundraising round. Just by throwing in some hyped jargon into the conversation, the entrepreneur was able to get the investor excited. He got a commitment from the investor for several million dollars within an hour on the phone.

This is not how VC investors (should) operate. However, there are three different pressures I see VC investors going through during the good times that can perhaps help explain this behaviour:

- There is a good supply of capital from LPs and an urgency to deploy.

- There is a lot of demand for capital from startups, and it is hard to separate the noise.

- The market is quite active, increasing the fear of missing out (FOMO).

Even the best and the biggest VC investors can sometimes struggle to get into the best deals during these times. Entrepreneurs who know what they are doing line up several investors they can choose from. Therefore, they are careful about whom they want to take capital from. It is a market when people at the bottom of the pyramid do have some say.

Some new attractions for VC investors have been Fintech between 2014 and 2018, Blockchain at the same period and the other hyped up technologies such as AI and Quantum Computing. These technologies are used by entrepreneurs in their pitch decks to lure investor attention. Some investors see through these hype words and focus on the ‘So what?’. They like to see that the technology is used to solve a genuine problem. However, in most cases, investors succumb to the FOMO pressures and go with the crowd.

From the perspective of a startup, there is one group of investors whom they should not ignore. They are the rich families, UHNWIs and HNWIs who have typically made their money through other ventures or inherited wealth that they would like to invest. This group of investors operate differently from institutional investors such as pension funds and even VC funds.

HNWIs often make decisions quicker than institutions, thus saving precious time for an early-stage entrepreneur. A business looking at a quick fundraise should definitely consider this group of people. There is more structure if not science to the investment decisions of institutional investors.

When businesses are at an early stage, there is very little data to demonstrate the viability of their business models. HNWIs and family offices can generally tolerate that and can get the vision of the entrepreneur without needing too many data points. The due diligence processes with these investors are shorter and lighter than institutional investors. More tips and techniques in approaching investors are provided in Chapter 6. Please see Figure 1.4 for the gist of this chapter.

FIGURE 1.4 Chapter One Sketch

Conclusion

In this chapter, I wanted to bring to light the macroeconomic factors that an entrepreneur needs to understand. When a central bank slashes interest rates, when oil prices fall, when a data policy takes effect across a region, there are ramifications across the innovation ecosystem. A good understanding of this will help entrepreneurs make contextual decisions.

We discussed the capital pyramid and how capital is distributed across the different tiers. We went through the motivations and the incentive structures of various stakeholders in the pyramid. We focused on VCs, CVCs, NWIs and family offices a bit more than the other actors because they are more relevant from a funding standpoint. Startups need to see this structure as a chain of actors who make money work for the whole system.

VC investors are not where the buck stops, and they have their own capital raising to do. Their investors, called limited partners, are typically endowments, pension funds and sometimes large family offices and corporations, too. Therefore, startups need to understand the source of funding for VC investors and how that source will behave during times of market ups and downs.

We see several virtuous cycles in a booming economy due to transactions that happen throughout the pyramid. The balance of these cycles must be maintained in a healthy optimal economy where there are no systemic issues emerging. That is the role of central banks in an economy. They strictly monitor several macroeconomic variables and fine-tune the economy through tools such as interest rates and quantitative easing.

During market highs, there are several pressures on investors to deploy capital. There are psychological pressures on them as they fear missing out on a deal even when it is a mediocre one. They might also have demands from their LPs who may make them deploy capital with a sense of urgency. This starts as sporadic investor behaviour and soon becomes systemic resulting in an overheated economy, needing to be corrected.

In Chapter 2 we will see how crises have happened in the past and understand key patterns and takeaways from the recessions since the 1980s.