Introduction: What's the Problem?

After successive school years disrupted by masks, isolations, and mass experiments in remote teaching, educators at last returned to school last year to find that classrooms and students had changed.

In the first days of the return, perhaps we didn't see this fully. Yes, most of us knew that there would be yawning academic gaps. Most of us understood what the data have since clearly borne out: that despite often heroic efforts at remote instruction, the result has been a massive setback in learning and academic progress, with the costs levied most heavily on those who could least afford it,1 and that it will take years, not months, to make up the loss. But at least we were all together again. We were on the road back.

As the days passed, though, a troubling reality emerged.

The students who came back had spent long periods away from peers, activities, and social interactions. For many young people—and their teachers—the periods of isolation had been difficult emotionally and psychologically. Some had lost loved ones, while others had to endure months in a house or apartment while everything they valued—tennis or track or drama or music, not to mention moments of sitting informally among friends and laughing—had suddenly evaporated from their lives.

Even if they had not experienced the worst of the pandemic, most were out of practice at the expectations, courtesies, and give-and-take of everyday life. Their social skills had declined. They looked the same—or at least we presumed they did behind the masks—but some seemed troubled and distant; some struggled to concentrate and follow directions. Some didn't know how to get along. They were easily frustrated and quick to give up. Not all of them, of course, but on net there was a clear trend. The media was suddenly full of stories of discipline problems, chronic disruptions, and historic levels of student absences. In schools where no one had ever had to think about how to deal with a fight, they burst into the open like brushfires.

At the time we needed good teaching the most, it was suddenly very difficult to accomplish, and young people seemed troubled and anxious. It didn't help that we were short-staffed, straining just to get classes covered. In the end it's possible that the first post-pandemic year was harder than the pandemic years themselves. The students who came back were not the students we'd had before the pandemic.

But, we argue, the story is more complex than it appeared even then. What had happened in the lives of our students wasn't just a protracted once-in-a-generation adverse event, but the combined effects of several large-scale, ground-shifting trends reshaping the fabric of students' lives. These events had begun before the pandemic, but they were often exacerbated by it. Their combined effects are significant, and probably not fully reversible. We can't turn back the clock. But they should cause us to plan and design our schools and classrooms differently going forward—not just for a year or two of “recovery” but perhaps more permanently.

In this introduction, we'll examine three unprecedented problems our young people face: 1) a crisis of mental health amid rising screen time, 2) a lack of trust in institutions, and 3) the challenge of balancing the benefits individualism with the benefits of collective endeavor in institutions that rely heavily on social contracts. We should note that this book is not all doom and gloom: the rest of it will be focused on solutions to the issues we describe. And we believe the solutions are out there. But first we have to be clear-eyed about where we stand.

A PANDEMIC WITHIN AN EPIDEMIC

Even before the pandemic, the psychologist Jean Twenge had found spiraling dosages of depression, anxiety, and isolation among teens. “I had been studying mental health and social behavior for decades and I had never seen anything like it,” Twenge wrote in her 2017 book iGen: Why Today's Super-Connected Kids Are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy—and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood.

This historic decline in the psychological well-being of young people coincided almost exactly with the precipitous rise of the smartphone and social media and more specifically with the moment when the proportion of social media users was high enough that any teenagers wishing to have normal social life no longer had an alternative but to become users themselves. It also coincided with the moment in time when the “Like” button was added to social media apps. As a result, social media use became far more compulsive and users far more dependent.

“The arrival of the smartphone has radically changed every aspect of teenagers' lives, from the nature of their social interactions to their mental health,” Twenge and co-author Jonathan Haidt wrote in the New York Times.2 “It's harder to strike up a casual conversation in the cafeteria or after class when everyone is staring down at a phone. It's harder to have a deep conversation when each party is interrupted randomly by buzzing, vibrating ‘notifications.’” They quote the psychologist Sherry Turkle, who notes that we are, now, “forever elsewhere.”

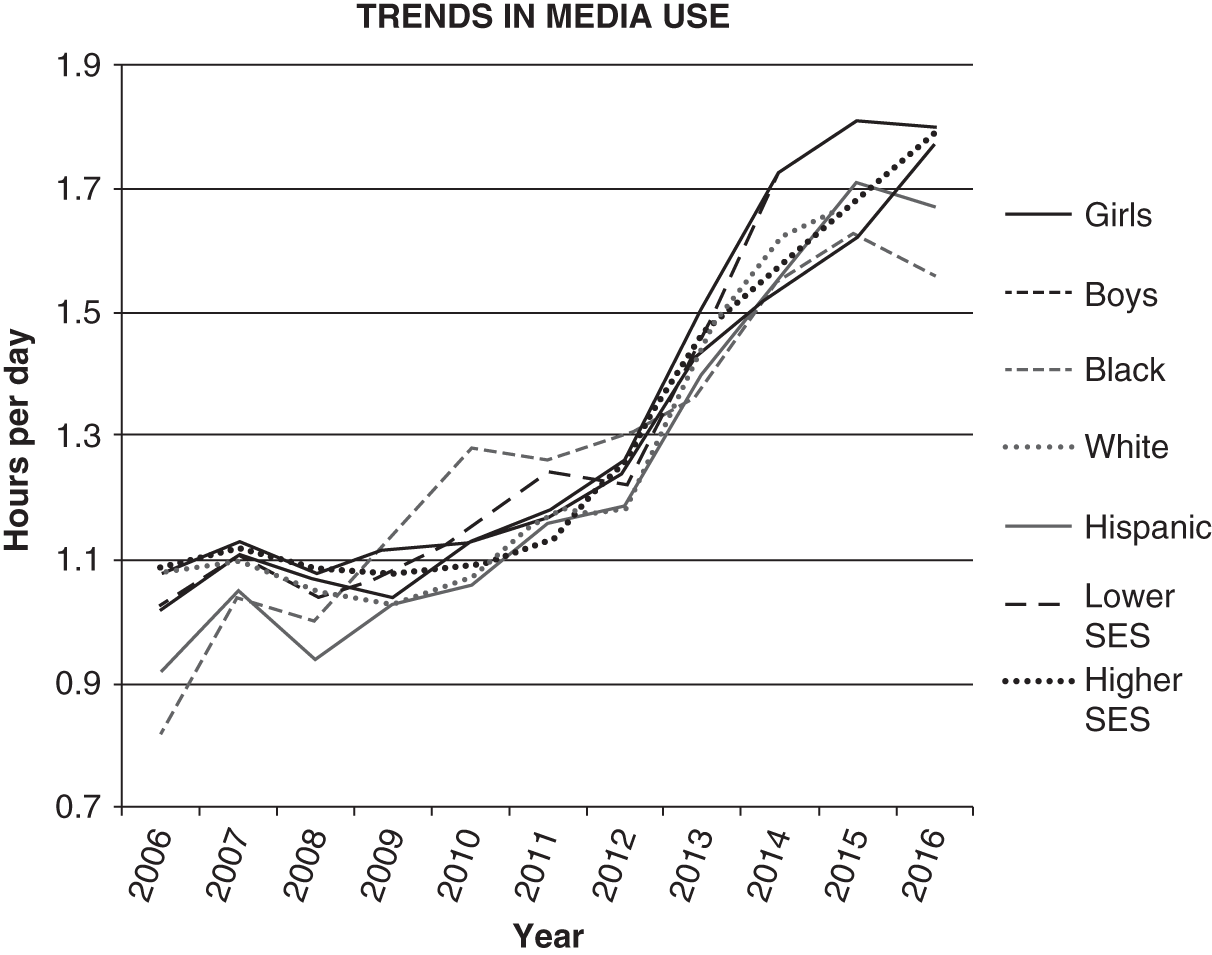

By the time Twenge published iGen, screen media use had doubled in ten years—across gender, race, and class—from an hour a day to two.3

By this point 97% of 12th graders (and 98% of 12th-grade girls) were then using social media. It was “about as universal an experience as you can get,” Twenge noted. And these data predate the newest and most addictive social media apps, such TikTok, which was released in 2016 and whose influence is not fully reflected in it. But the results were still plenty alarming. Twenge and Haidt found that across 37 countries, teenage loneliness, which had been “relatively stable between 2000 and 2012, with fewer than 18% reporting high levels of loneliness,” suddenly spiked as smartphones and social media proliferated. “In the six years after 2012, they wrote, “rates…roughly doubled in Europe, Latin America and the English-speaking countries.”

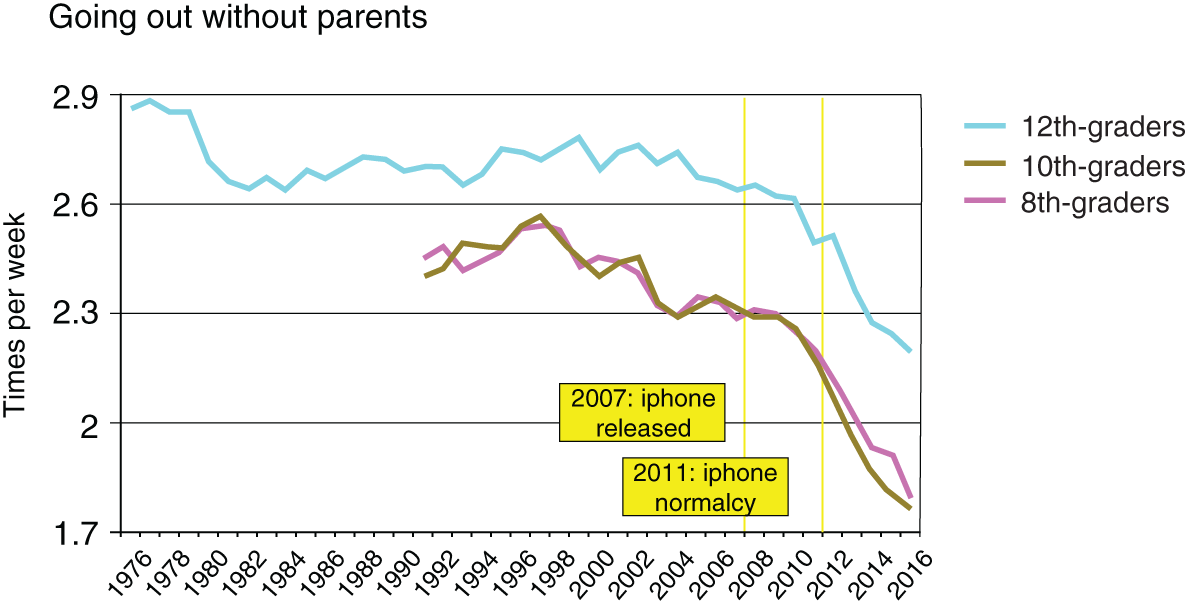

This was already an epidemic reshaping every aspect of teen's lives. As the following chart shows, the average 12th grader in 2016 went out with friends less often than the average 8th grader ten years before, Twenge pointed out. Instead of hanging out at the shopping mall, meeting up at a McDonalds, or cruising around in cars, they were in their rooms interacting on social media (or gaming, especially if they are boys). And even when they were “out and about” they were often not fully present.

The tendency of young people to socialize online and from their rooms instead of in person has had a wide variety of consequences—both good and bad, Twenge is careful to point out. Far fewer had sex, drank, or used drugs. The teenage pregnancy rate dropped to its lowest in decades. Teenagers became less likely to die in car accidents. But they didn't learn the responsibility and social skills you get from being out in public—having a job, doing volunteer work, meeting new people, learning to drive, even going to parties. (By the way, they did not spend any more time doing homework, in case you're wondering, which suggests that the common theory that school-related workload was the source of rising mental health issues is not likely true.) The number of young people who got insufficient sleep increased to unprecedented levels. And most of all, and far most importantly, rates of depression, anxiety, loneliness, and even suicide spiked suddenly to all-time highs, at rates Twenge had never seen the equal of.

Meanwhile, young people's intellectual lives were changing too. In competition with the cell phone and social media, the idea of reading a book for pleasure had all but disappeared. As recently as 1996, half of teens regularly read for pleasure; by 2017, only one teen in ten did. And reading had become a different activity. Those teens who did read mostly did so not as older generations did—via deep immersion in another world, with sustained empathy-building experiences and little interruption, for long periods of time—but as they do other activities: with their cell phones by their side interrupting them every few seconds with a “push” message. Their internal narrative, the one in which they discover why the caged bird sings, is mixed with equal amounts of reflection on what is up with the Kardashians and “Dude, where R you?? We R Over @ Byrons!”

Young people had traded social relationships for virtual ones, but at a high cost. The nature of virtual interactions conducted on social media is engineered by a third party—app creators—whose purpose is not to create true connection but dependence. As a result, even social acceptance on social media can be problematic. The Like button (first added to social media platforms in 2009) in particular is designed to manipulate our desire to connect socially to create product addiction. It creates “short-term, dopamine-driven feedback loops.”4 Getting a like communicates social approval and inclusion to us. This releases a bit of the same brain chemical (dopamine) released by other pleasurable activities. Social media algorithms ensure that the tiny chemical dividend is released on a variable unpredictable reward schedule: you don't know when and whether you will get the little burst of well-being that comes with a like; its schedule is unpredictable so you are socialized to constantly check for it. Such feedback loops highjack our evolutionary desire for social inclusion and translate it into digital currency. For teens, whose need for validation and affirmation is especially high, it makes their lives a constant public popularity contest.

Like buttons are catnip for brains, in other words, but the results of being unliked are worse. “It used to be that if you were bullied at school, you went home to your family. You were able to leave that negative environment. You were safe. You got a break from it. That allowed you to deal with it. Now if you are bullied online, it's in your pocket. It's in your room with you. You are never free. You are never safe,” noted Cristina Fink, a Rowan University psychologist, in a recent conversation.

In 2017, Twenge had found that the most reliable antidote to the negative effects of social media and extensive screen use was sustained, in-person social interaction—away from phones and in direct engagement with others. The most powerful effect was often in the little things: smiling at one another, sharing a laugh, working together to accomplish some small, shared task like blocking stage positions for Act 3, Scene 1. Young people who played sports were far less likely to experience anxiety and depression, because they had an extended and enforced break from their phones and because when they were off their phones, they had connection-building social interactions to balance them.

But the numbers of kids who engaged in organized activities was declining. By 2019, a report by Common Sense Media found that the average teen spent more than seven hours per day on screens. Nearly two-thirds spent more than four hours per day on screen media.5 For almost 30%, the average was eight hours a day.6

And then in 2020, the pandemic hit, and everything that might have offered such an alternative to screen time suddenly disappeared. When youth were not in school, not at practice, or not at the mall with friends, they were on their phones. Common Sense Media updated its findings in March 2022, reporting that screen and social media use had risen sharply during the pandemic, with the average teen and preteen spending more than one extra hour on screen media on top of already intense levels of exposure. Daily screen use went up among tweens (ages 8 to 12) to five and a half hours a day on average and to more than eight and a half hours per day for teens (ages 13 to 18). Low-income families were hit hardest, with parents most likely to have to work in person and fewer resources to spend on alternatives to screens.

At these levels of use, smartphones are catastrophic to the well-being of young people. “It's not an exaggeration to describe [this generation] as being on the brink of the worst mental-health crisis in decades,” Twenge writes.

And the problems aren't limited to mental health. All that time on screen degrades attention and concentration skills, making it harder to focus fully on any task and to maintain that focus. This is not a small thing. Attention is central to every learning task, and the quality of attention paid by learners shapes the outcome of learning endeavors. The more rigorous the task, the more it requires what experts call directed (or sometimes selective) attention—defined as “the ability to inhibit distractions and sustain attention and to shift attention appropriately,” according to Michael Manos, clinical director of the Center for Attention and Learning at Cleveland Clinic. In other words, to learn well you must be able to maintain self-discipline about what you pay attention to.

The problem with cell phones is that young people using them switch tasks every few seconds. Better put, they practice switching tasks every few seconds, so they become more accustomed to states of half-attention, more expectant of new stimulus every few seconds. When a sentence or a problem requires slow, focused analysis, their minds are already glancing around for something new and more entertaining.

The brain rewires itself constantly based on how it functions. This idea, known as neuroplasticity, means that the more time young people spend in constant half-attentive task switching, the harder it becomes for them to maintain the capacity for sustained periods of intense concentration. After a time, a brain habituated to impulsivity rewires to become more prone to that state. “If kids' brains become accustomed to constant changes, the brain finds it difficult to adapt to a nondigital activity where things don't move quite as fast,” Manos continued.

Though all of us are at risk of this, young people are especially susceptible. Their prefrontal cortex—the region of the brain that exerts impulse control and self-discipline—isn't fully developed until age 25. In 2017, a study found that undergraduates (more cerebrally mature than our K–12 students and so with stronger impulse control) “switched to a new task on average every 19 seconds when they were online.” It's a safe conjecture that younger students can sustain even less attention.

In other words, any time young people are on a screen, they are in an environment that habituates them to states of low attention and constant task switching. At first our phones fracture our attention when we use them, but after a time our minds are rewired for distraction. Soon enough our phones are within us.

LOSS OF FAITH IN INSTITUTIONS

Along with its effect on the lives of students and their social media usage, the pandemic has overlapped with and probably exacerbated another important social trend affecting students, schools, and educators: declining levels of trust in institutions. In their November 2020 report, Democracy in Dark Times,7 professors James Hunter, Carl Bowman, and Kyle Puetz describe a “slowly evolving crisis of credibility for all of America's institutions.” While the clearest places of declining credibility are (in this study and others) government and the media, declining faith in “the government's ability to solve problems,” as the authors put it, also affects other institutions of public life, including schools.

The long-term trend, which began in the latter years of the 20th century but has accelerated since, shows citizens increasingly perceiving institutions as “incompetent” and “ethically suspect.” This creates a legitimation crisis: people are far less likely to accept or support decisions from an institution they don't trust. They are less likely to contribute their time and effort to its initiatives. All this, of course, makes it harder to run those institutions effectively.

By mid-pandemic, the results of this disaffection ran deep. Half of all Americans, regardless of politics, said that there were days when they “felt like a stranger in my own country.”

We should pause here to define the word “institutions.” The political analyst Yuval Levin defines them as “the durable forms…of what we do together. They're clumps of people organized around a particular end, and organized around an ideal and a way of achieving that important goal.”8 The range of institutions in American life is broad. An institution can be specific (a school district) or more abstract (public education).

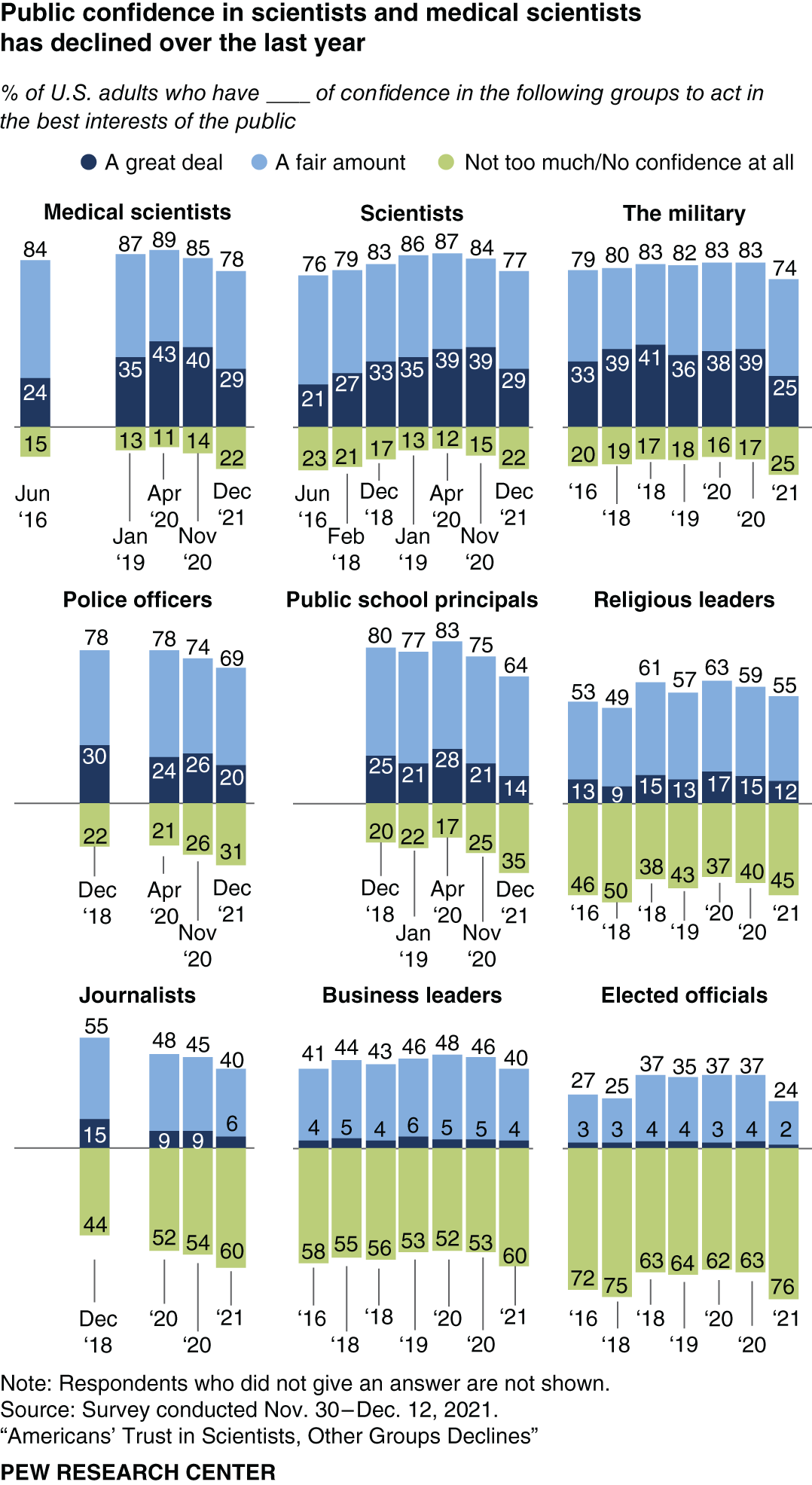

The decline of faith in institutions affects schools directly, since they themselves are institutions. Schools can no longer count on receiving the goodwill and trust of the parents they serve. We can see this trend clearly in the data. The Pew Research Center, for example, regularly asks a wide sample of Americans about their faith in specific authority figures in various institutions. In early 20229 they found that, for example, faith in journalists had declined steeply. In 2018 more than half of Americans—55%—said they trusted journalists “a great deal” or “a fair amount,” while 44% said “not too much or not at all.” By 2022 the number had flipped: 40% of Americans trusted journalists, 60% did not. The level of mistrust in the profession increased by 50% in four years. Faith in elected officials declined slightly from already dismal numbers (perhaps there wasn't much farther those numbers could go).

These were among the professions with the greatest erosion of trust, but notice that the data also ask specifically about public school principals. There too we see significant declines. In 2018, 80% of Americans trusted school principals a fair amount or more. Only 20% were at “not much confidence” or less. In 2022 the trust numbers had declined to 64% and the mistrust numbers were at 35%. They had almost doubled.

It's worth noting that within the general trend—declining trust—the numbers show two subtrends. The first is increasing skepticism from the majority of parents. It's going to take a little more work to make them see they can believe in their school and its capacity to get its core work of educating children done well. Then there is a separate trend of people who feel outright mistrust. These are families who may fight the school's policies if their skepticism is not effectively addressed.

This is critically important. Like the nations they are a part of, schools are institutions that rely on a social contract to do their work. Participants agree to accept relatively minor restrictions on their own actions in order to participate in the larger, more important benefits that accrue when everyone follows those rules. As a citizen, I accept that I will not steal my neighbor's possessions, no matter how much I want them. In return, I live in a society where everyone's possessions are secure, where it is worth having possessions because you are likely to keep them, and where people invent things worth having because others will value them, which they are only able to do if they can protect them. Want a vibrant entrepreneurial economy? Start with property rights.

Schools rely on a version of this social contract as well. As a student I accept that I will not shout out things in class and disrupt instruction so that others can learn; I benefit from the fact that I now have a space in which I can plausibly aspire to become what I dream of in life. As a parent I accept that my child will be asked to accept this social contract. This is to say that every school lives or dies on people's willingness to accept that authority is not just different from authoritarianism but benign and in fact beneficial—necessary to the construction of a social contract. That contract only works when participants trust the leader of the school to determine the terms of the contract. It does not take a majority rejecting the terms of a social contract to erode its viability. A handful is enough.

While we are talking about trust in schools, it's worth looking at one more data point. The Pew data above are specific to principals. How do people feel about their schools overall? The polling organization Gallup has been asking Americans the following question since 1973:10 “I am going to read you a list of institutions in American society. Please tell me how much confidence you, yourself, have in each one—a great deal, quite a lot, some or very little.”

Here are the responses when respondents were asked about public schools.

The long-term trend is clear. Over the 50 years that data have been gathered, confidence in public schools has declined steadily but pervasively. The percentage of respondents who felt “quite a lot” of confidence or more has dropped by half. Even in the first decade of the 21st century, numbers were routinely 10 points higher than they were in 2021.

This larger trend was broken by a short uptick of goodwill in 2020—our long pandemic year. Americans appeared to be grateful for the efforts of schools to respond to the crisis and were more forgiving and appreciative in their responses. But that uptick was a brief honeymoon. The data snapped back quickly.

The converse trend is also clear. The percentage of respondents who feel very little trust in their public schools has almost tripled in the years since the survey began. The lines now nearly touch. The average parent is just as likely to start at a point of mistrust as he or she is at a point of trust. Things are likely to stay that way or even get worse. Many parents' experience during the pandemic—their frustrations or outright anger with masking or distance learning, the historical rates at which they withdrew their children—will not soon fade from memory. Those are difficult conditions under which to hope to build and defend a new social contract. Schools face a clear challenge in the fact that the families they intend to serve feel less faith in their reliability, skill, and trustworthiness.

Meanwhile, a secondary challenge also looms. As schools struggle to operate in a climate of mistrust, the institutions composing the ecosystem schools work within—religious institutions, cultural institutions, those institutions that offer programs like sports and music and drama that connect young people throughout their community—are also struggling.

One result of the increased lack of trust in these institutions is lowered levels of participation in them. As a result, people are more and more likely to connect online instead of in person, say at a church or an activity or even a community meeting. Young people are less and less likely to infer codes of mutuality and cooperation from those institutions. In those places, they are more likely to meet with people whose beliefs and values do not mirror their own. Without them, they run the risk of living in an echo chamber where initial perceptions are easily reinforced and where people who disagree are vilified, their motives suspected.

Individuals who live in these sorts of environments rarely have cause to challenge or change their ideas and perceptions. Jonathan Haidt's research in The Righteous Mind makes this clear: people change their minds when people whom they trust and feel a connection to express a differing perspective. An adversary castigating you or impugning your motives almost never changes your mind or broadens your views. You change your mind or moderate your assumptions because someone whom you admire or appreciate in some other way holds a different opinion. The fact that people—particularly teenagers—are now less and less likely to meet and connect with people who are less like them in thought or background means the risk of increased cultural isolation (and probably political polarization) as well.11 The declining trust in institutions not only makes schools' missions harder but also exacerbates the isolating effects of social media on students.

THE TENSION BETWEEN INDIVIDUALISM AND BELONGING

The final key challenge students and schools face today is how increasingly individualistic our culture is, often at the cost of communal orientation and mutual obligation.

The Dutch social psychologist Geert Hofstede defined individualism as “a preference for a loosely knit social framework in which individuals are expected to take care of only themselves and their immediate families.” Its opposite, collectivism, is “a preference for a tightly knit society in which it is understood and expected that members of the group will look after each other in exchange for mutual loyalty.” Hofstede ranked societies on a scale of 1 (maximum collectivism) to 100 (maximum individualism). China—a society grounded in Confucian roots that stress principles of mutual obligation—scores a 20. Brazil, also a relatively collectively inclined society, scores a 38. Western nations tend to be the most individualistic. Germany scores a 67. But the US scores the highest of any nation: a 91, with the UK not far behind.

Not only is the United States currently the most individualistic society in the world, it's also a safe bet that we are the most individualistic society in the history of humankind. As you might guess, the shift to modernity has been a shift away from a collective mentality. As Jonathan Haidt puts it, most societies historically chose the “sociocentric” answer—a belief in communal bonds—until in the 20th century, when “individual rights expanded rapidly, and consumer culture spread.” An individualistic orientation replaced a “sociocentric” one. In other words, individuality is a modernist tendency.

We want to be clear: we're good with individualism. Much of its rise is a reaction to the destruction of individual rights and freedoms demonstrated by totalitarian regimes of the 20th century. It's hard to watch the erosion of individualism in Russia and China today and want to trade.

But we also think it's important to recognize the ways in which our culture's extreme emphasis on individualism, even with its upsides, might benefit from moderation—and might cause us to overlook ways of doing things that might create a stronger sense of belonging and that might be therapeutic in times of difficulty and disconnection.

After all, as highly individualistic societies, we are temperamentally resistant to many of the key tenets by which purposeful groups are formed. The social order, Jonathan Haidt writes in The Righteous Mind, is “built around the protection of individuals and their freedoms” and far less so our mutual obligations. “Any rule that limits personal freedom can be questioned,” Haidt writes. “If it doesn't protect somebody from harm then it can't be morally justified.”

Those are challenging terms on which to build community and mutual obligation. Talking to people in a highly individualistic society about sacrifice and the broader good—in society, in schools, in a pandemic—is challenging and invariably runs up against resistance. But a viable social contract in which people routinely defer and relinquish their short-term desires and impulses (I don't feel like doing what my teacher asks) to the greater common good of a shared endeavor (if I do that I keep her from teaching myself and others) is a necessary condition to schools that foster achievement and well-being.

WE'RE OPTIMISTIC, ACTUALLY

We apologize if the first part of this introduction made you anxious. It feels at times like a litany of woes. At times it was hard going, emotionally, to write it. But things get brighter from here. Now that we have framed the problem we can get down to solutions. And there are solutions, we believe: clear steps schools can take to respond to each of these challenges successfully. We are deep in the forest. It might seem hopeless. But there are breadcrumbs to follow. It's not going to be easy, but we humbly hope we can help schools find a path out of the woods.

Consider, for example, a meeting we recently observed—or more precisely three of us observed. The fourth, Denarius, was running it. The meeting was with a group of students at Uncommon Collegiate Charter High School in Brooklyn, where Denarius is the principal. He was soliciting his student's input on their experience regarding a series of school policies and decisions in preparation for a strategic planning session with his co-leader.

It was a case study in what something we'll discuss more extensively in Chapter 1, process fairness, can look like. In some cases, Denarius wanted the students' input on decisions he was actively making or thinking of revising. In other cases, he just wanted to know what students thought of things that seemed fine to him. How should morning arrival work? What should the latest tweaks to cell phone and uniform policies be? What events and activities in the school did the students value? If they had a magic wand and could change one thing about the school, what would it be and why?

In one case he had a specific purpose, and in the other he was just in the habit of constantly gathering input, of listening well as a matter of course. It's worth noting that in the first case, listening and asking students' opinions did not imply that he would agree or give them what they wanted. Several students argued for the convenience of scanning into school as soon as they arrived, then having space to change into full uniform and proceed to class. Denarius listened carefully. He was smiling. He explained that in a previous year, they had tried that had students scan into school as the first step in the system, but had changed it after many students had been late to classes because they'd lingered in the cafeteria (and stairs). Scanning into school last and outside of the cafeteria had resulted in higher rates of students being on time to class. “Do you want to see the data?” Denarius asked, again warmly and smiling. In his mind it was a good thing that students wanted to ask about the policies, even though he was confident he knew what the right decision was on this specific question.

Still, the fact that he valued them enough to constantly ask their opinions and to show them data about the decisions he made built process fairness. The students felt like the school valued their opinions and took them into account. It resulted in trust and appreciation even though many, even most, of the decisions were not what students had asked for. (Some of them were. “I always try to find at least one ‘yes,’” Denarius said.) Suddenly, they saw the reasons more clearly, how they aligned to their goals and weren't arbitrary. They not only accepted the decisions; they understood and came to agree with them. In the end, many students appeared happy not to get what they asked for!

There wasn't anything rocket science-y about the meeting Denarius held. Just careful listening and taking the time to ask and explain—and being okay with constructive criticism from young people. He and a colleague were taking notes when students spoke. That small detail said: Your words are important to me. So did their ability to talk about values and goals without talking down to young people. Laughing occasionally helped too—laughter tells people we are connected. So did the fact that he was smiling. Students who care enough to discuss or even argue about policies are engaged students, and that's a good thing. They should feel that we listen and value that, whether or not they get their way. In fact, a good rule of thumb, we think—for running schools and possibly more broadly—is that the most important time to listen is when you think you disagree.

We bring up this example to show that it's possible to combat the effects of the pandemic, the epidemic, and the rising tide of mistrust that our students are facing, and to help them feel a sense of belonging in their schools. We will come back to the idea of belonging in this book—to the question of how we create schools that foster it in students. When schools do that, we argue, they create community—a mutual expectation of shared benefit and shared obligation. When those things happen, you have something like a village—an entity that sits within a larger society, that has a distinct culture, a social contract of reciprocity, and which prepares people to thrive as a group within it and in the larger society as a whole.

Every day, people in schools do things like what Denarius did in his meeting. Our goal in this book is to source them and describe them for you. We'll tell you about how Charlie Friedman and his staff in Nashville redesigned extracurriculars to build a greater sense of belonging at his school, Nashville Classical. We'll tell you how Sam Eaton and her colleagues at Cardiff High School in Cardiff, Wales, reengineered recess to allow students to connect and build relationships and relationship-building skills. We'll show you videos of Ben Hall teaching his students to talk to rather than past each other so they feel a sense of belonging while they learn.

It's a challenging time, but this is a hopeful book that seeks to honor and share the problem-solving already done by educators like you.

We should note that the schools whose ideas we draw on have set out to build a wide variety of cultures in a wide variety of ways. They are all inclusive and academic cultures, but there is not just one version of what a school culture characterized by such things looks like. There are variety of ways this can be built. What these school cultures have in common is that they are all carefully designed and implemented. There are principles to help a school do this, but no one “program,” no one model of what a school that helps young people thrive must look like.

With that in mind, here's a bit more about what's ahead.

In Chapter 1, “How We're Wired Now,” we'll explore more deeply the challenges we've raised in the introduction and begin pointing to some solutions. We'll try to draw on what we know about the evolutionary importance of connection and belonging to human well-being, what we know about how smartphone technology has affected young people, and what we know about rebuilding trust in schools as institutions to sketch the path forward.

In Chapter 2, “A Great Unwiring,” we'll dig deeper into technology. We start with some of its benefits, but we'll also discuss its downsides and look practically at the reality: we need to restrict cell phone access during the school day. We know that won't make us popular, and that's why we spend a significant amount of time explaining the why behind the unwiring we think our students deserve. Doing so is going to be difficult, so we'll get practical about how schools can make such a hard decision successfully.

In Chapter 3, “Rewiring the Classroom,” we'll start talking about how schools can design themselves to best serve students given where they are now, and we'll begin with the classroom. We'll show how we can “wire” classrooms to constantly send signals of belonging to students, even as teachers retain their critical focus on academics. Classrooms must ensure that students feel connected and that they learn as much as possible. We cannot allow it to become a choice between these things. Many readers will be familiar with Doug's Teach Like a Champion books. Chapter 3 discusses how to apply, adapt, and prioritize some of the techniques from that book, given the realities of here and now. We'll share videos too. There's a lot more to beating the current crisis than outstanding day-to-day teaching, but in the end, we can't win the struggle without it.

In Chapter 4, “Wiring the School for Socio-emotional Learning,” we'll talk about rewiring the socioemotional work of schools. We'll focus on character education and the instilling of virtues that promote individual and group well-being. We'll share powerful research on the value of resilience and gratitude and how to use them to help ensure that students are happy and connected and fulfilled.

In Chapter 5, “Case Studies in the Process of Rewiring,” we'll talk about the planning processes that are required to design and operate our schools more effectively in response to the current challenge and will examine a few case studies: how extracurricular activities could be redesigned, how culture could be redesigned, and in particular how we could rewire what we do when student behavior breaks down.

We close with an afterword, “How We Choose,” a brief coda on the role that school choice might play in building more responsive and connected schools. Throughout the book we discuss the importance of a social contract to a viable institution—people have to accept sacrifices of personal freedoms in order to achieve shared mutual gains. Doing that is harder in a more fractured society. But a broader vision of choice where parents select schools for their purposes could help us to give more families more of what they want and massively reduce the practical difficulty of running excellent schools at the time we need them most.

Notes

- 1. https://emilyoster.net/wp-content/uploads/MS_Updated_Revised.pdf; https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/05/briefing/school-closures-covid-learning-loss.html among others

- 2. Jean Twenge and Jonathan Haidt, “This Is Our Chance to Pull Teenagers Out of the Smartphone Trap,” New York Times, July 31, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/31/opinion/smartphone-iphone-social-media-isolation.html

- 3. Two hours a day may not seem like much—by the end of Chapter 1 it will seem positively quaint—but 2 hours a day times 7 days a week times 52 weeks a year means 728 hours. Leave 8 hours for sleep and divide by the remaining 16 hours in a day and that's 45 days—45 days of not playing soccer, being in the school play, reading, or spending time with friends, and replacing it with something that creates anxiety, isolation, and unhappiness.

- 4. https://sitn.hms.harvard.edu/flash/2018/dopamine-smartphones-battle-time/

- 5. https://www.cnn.com/2019/10/29/health/common-sense-kids-media-use-report-wellness/index.html https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/24/well/family/child-social-media-use.html#:~:text=On%20average%2C%20daily%20screen%20use,(ages%2013%20to%2018)

- 6. It's often difficult to break out how much of that is social media use because teens are constantly switching back and forth among apps. Surely the time is fractured and almost always with social media “on the brain.” It's also worth noting that these data are based on self-report. The real numbers are probably higher.

- 7. https://iasculture.org/research/publications/democracy-in-dark-times

- 8. https://www.hoover.org/research/importance-institutions-yuval-levin-1

- 9. https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2022/02/15/americans-trust-in-scientists-other-groups-declines/

- 10. https://news.gallup.com/poll/1597/confidence-institutions.aspx

- 11. Jonathan Haidt discusses the connection between social media and political tension and polarization here: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2022/05/social-media-democracy-trust-babel/629369/