Chapter 5

Case Studies in the Process of Rewiring

In this chapter we'll discuss how we think a few key aspects of the way schools are designed might be adapted to better respond to students' needs, given the challenges we discussed in Chapter 1. Obviously, not every action we discuss will be relevant for every school and the word adapt could imply anything from a slight tweak of the current emphasis to a complete overhaul. We'll start with a story a colleague told us about rethinking extracurriculars through a belonging lens. In part we'll share it because some of his specific adaptations will be relevant for other schools and in part because we think the broader reflective process—assembling a group to rethink long-established components of what a school does in light of new and changed context—is a critical tool for schools in their current context. Our goal, in other words, is to jumpstart a process of strategic reflection. While we suggest a few key areas where we think that kind of reflection is especially critical—how extracurricular activities are designed, how school leadership spends its time, and how schools could think differently about what happens when student behaviors harm school culture—we hope that's just the beginning and the examples we discuss here will be easily applied to other relevant topics.

Let us begin at the beginning. We noted that the activities Jean Twenge described that appeared to have the strongest effect in mitigating loneliness, depression, and anxiety in young people were things like sports or religious services—group activities that implied steady involvement, shared purpose, cooperation, and active engagement. They are settings in which Martin Seligman's components of happiness would be present: students take pleasure in such activities, of course, but also feel engagement and find meaning. They're activities that build a sense of identity. And they're places where it would be odd to have one's phone out. We want more of that—or at least more high-quality provision of that—for our young people. And obviously schools play a big role in that.

But the calculus of running extracurriculars has changed. With students spending more of their time on their phones, they are less likely to join things at school. One principal described walking by the classroom where the once-vibrant debate club was meeting. It was just after school. There were five or six kids in the room—not enough of them to really do what they normally did—so they were waiting in hopes that others would show up. Several students were on their phones; perhaps they were texting friends to encourage them to come but perhaps they were just doing what all of us do nowadays when we're required to wait—scrolling. And this had the effect of making the room seem even more lifeless. There weren't enough people and those who were there seemed only half present.

Those five or six kids loved the club let’s assume. It filled a role in their lives—they hung out with the other kids from the club. A few might have even thought of themselves as “debate kids.” But how many of them would come back next Tuesday after an experience of waiting in a half-empty room for an activity that would never happen? The club was dying, in other words. The principal had walked by to witness one of its last meetings, ironically at exactly the time students needed it most.

Extracurricular activities offered in schools are incredibly important. They fill young people's lives with meaning, provide new experiences, and most of all offer connections, cooperation, and rich interaction with peers. But creating more engagement in activities is no longer quite as simple as throwing open the doors to classrooms and letting the Model United Nations and the Spanish Club file in.

This brings us to Charlie Friedman, who runs Nashville Classical Charter School in Nashville, Tennessee, and whom we discussed briefly in Chapter 2. Charlie was not the school leader we described above, walking through his building to see the debate club's last breaths. But he did feel his students' isolation strongly and he believed that extracurricular activities in his school could be better, so he assembled a group of seven colleagues in his office. The seven played a diverse range of roles in the school: one ran the choir, one was a coach, one or two were simply “connectors,” teachers whom kids seemed to take to readily and who seemed to read them well.1 Charlie asked them to help him think about how to make extracurricular activities really sing. And he wanted to start with the why. “When the pandemic hit we had sixth graders [as our oldest students] and when they came back they were eighth graders,” Freidman told us. Not only had they missed most of their middle school years but the school, which was new and growing, was suddenly much larger. “And that provided a unique opportunity to step back and think about what the purpose was for extracurricular programs.” They basically landed on three things:

- One: To provide students with a sense of identity, to give them a chance to say, “I'm in the choir.” “I'm on the basketball team.” “I'm a cheerleader.” Charlie and his colleagues thought that was a powerful thing for a middle schooler to be able to do.

- Two: To give students an opportunity to build an informal relationship with a trusted adult.

- Three: To give students a chance to perform. Not every kid would be able to participate, but Charlie wanted to really try to incentivize and encourage people to watch performances and events so they felt more special.

Having laid out key principles to guide decisions, they asked themselves in a series of meetings: If those three things were true, what did that mean for their extracurriculars? They started to rethink them one by one, beginning with who led them.

“We put a little bit more money into the stipends for coaching and leading those programs than we normally would have and really tried to steer some of our strongest teachers and connectors to lead them, sometimes at the expense of their coaching ability but with the belief that this was about trusted mentors more than anything else.”

Ideally your tennis coach would be able to make you feel like you were a part of a team and make you look forward to practice, and be able to talk backhand grip and serve and volley tactics. But, the argument went, if you had to choose, the former was more important than the latter.

They also started to think about audience quite a bit, on two levels. First, if the purpose was to give kids a chance to perform, there had to be someone to perform for. If you spent all semester preparing for a play and 15 people showed up and they were all parents, that was different from how it felt if the parents showed up and so did a bunch of classmates, some whom you knew pretty well and maybe some you didn't. The next day they might say, “Hey, I didn't know you acted,” or you could say, “Thanks for coming to the play,” and suddenly you'd be connected.

Similarly if the gym seemed half empty rather than bursting at the seams, the game was a very different experience. The crowd needed to feel supportive and vibrant, both in numbers and in how they behaved. And as they thought about that, the group in Friedman's office started to talk about the idea that while not everyone could play, everyone could feel a part of the event as an audience member if they designed it right. They all knew people who'd chosen the college they attended in part for their big-time sports programs—not to play but to be a fan, to delight in flags flying and drums pounding, in dressing up or even painting your face, in chanting with the group. People chose a college for that. The experience of being in the audience was important. If they could engineer the audience experience, they would make each event more inclusive for those who watched and more meaningful for those who performed. As Friedman told us:

“We're a school that utilizes choral response and class cheers and chanting. We have a really strong music program. And I saw something in a book I read over break about the research around music and chanting and dance being sort of this fundamental human connection and why lots of religions use these things. It's just a chance to do things with lots of other people and your heart beats a little bit faster. And so we came out of winter break saying those things are really important and it is really important for kids to cheer and chant together and for a school to sing together and we should find ways to do that at all costs because I think that's actually part of what being in a community means.”

As a result, they spent a lot of time orchestrating what was happening in the stands during an event like a basketball game. This is to say, they redesigned the event by starting with the audience, and it's fascinating to think of how many ways you could take that idea and run with it. At college and professional sporting events, there's not only singing but often a section where, instead of sitting in clusters and haphazard groups, students can sit together and cheer as one. (Nashville Classical did that.) There are T-shirts being launched into the crowd, and competitions at half-time for the fans. (We're not sure if Nashville Classical has a T-shirt launcher but we're going to send them one.)

At college and professional sporting events, people ham it up for the camera on the jumbo screen. The camera is pointing at them in the first place to make them feel a part of the show. And it works. The camera points at people in a typical stadium and they stand up and cheer or dance. There really isn't any reason a school couldn't, in a simpler but still meaningful way, have cameras on the audience to make them part of the show. You might not have a jumbo screen to project on, but you could walk around interviewing and filming the crowd on your phone and post the video (or pictures) on Facebook afterwards. The “you” behind the camera could be school staff, of course, or it could be students, which would give more kids a way to have a meaningful role in the event.

To attend could be to join, and if it was, it would mean a vibrant crowd to support the performers and a vibrant crowd to belong to for the audience. Could you do the same or some version of it at the school play? Could you sell popcorn and give away a few T-shirts and walk around interviewing and filming so that people felt it was an “event” and they were part of it? School spirit is what they called that in a bygone era. Some of us might scoff at that phrase now. But then again, people felt far more connected to their school as a community then too.

The school also went all in on the idea of identity. To do that they did a lot of things that are characteristic of sports programs at bigger schools. (Nashville Classical is small.) “We planned a kickoff/spirit day to launch the season. Everyone got a T-shirt they wore to school. We had a teacher dress as the mascot, and so on. For kids on the team, we decorated their lockers. Kids on the team also got a ‘warmup’ shirt they wore to school on game days,” Friedman recalled. “Our first home game was the Tuesday before Thanksgiving, and we went out of our way to advertise it to our community. Because so many people had family in town or were about to be on a holiday, attendance ended up far surpassing expectations.”

At the last game of the season they held an “eighth grader” night for the girls' team, boys' team, and cheerleaders. “We announced the high school they planned to attend and each eighth grader gave a rose to a cherished teacher or family member [gratitude sighting!]. If you were a parent, a teacher, or another eighth grader, we wanted you to feel part of something bigger. Likewise, parents, families, and other students all wanted to attend to celebrate the students. We planned and hosted a banquet at the end of the season for all of the winter athletes and their families. We gave out awards, encouraged siblings to attend, and so on. Again, I think people did feel like they were part of something bigger.”

All of those things are rites of passage for the sports kids. Couldn't the kids in the play and in the choir have them too? Why not have T-shirts for them to wear? Getting opportunities to wear your basketball uniform or your choir T-shirt around school established identity. Having a choir T-shirt like the athletes get builds identity. Why not a last event for the eighth graders with a moment for them to express their gratitude?

And while sports programs can share some ideas about audience with other activities, sports can also learn some things from them. As we noted in Chapter 2, extracurriculars can be divided into two groups: those that require significant accumulated expertise, and those that one can join based on interest and affinity alone. Schools have to invest in both and make both kinds valuable. For tenth graders who have not invested years of their life in mastering the sport, the basketball team may not be an option. But the debate club, the Spanish Club, and maybe the school play are. Students should have communities of interest they can join regardless of whether they have been involved in them since their first steps. Both kinds of programs need to thrive—the ones that reflect a long-term commitment and the ones that you can just decide to try.

But one challenge Friedman and his colleagues thought about was the “you can't just decide to play” problem in sports. Selectivity was both a good thing and a bad thing in sports. Could they balance the two—find a way to broaden access? “When the year began, we held ‘open gym’ tryouts for two months. As a result, there was a large group of students who didn't end up being on the team but felt like they were part of the team. They made connections; they had played with the varsity.” Some of these students were younger and would be on the teams in a year or two, so there was a bit of “planting seeds for the future.” But some kids had just spent a month playing—their season was a month long instead of three but it was still a season. They had felt what it was like to be on the team and built connections and camaraderie.

Nashville Classical's solution might not be the right one for your school. But the process is one of the core themes of this chapter: What are the things we believe about this part of our school? What questions does this force us to ask? What might be some solutions?

And we want to pause momentarily on one of the questions Friedman and his team caused us to consider: the fact that sports are by far the most popular single extracurricular activity, but what about all those kids dying to play a sport at most schools? What about the kids who are marginal? Think from a larger societal belonging, well-being, and mental health perspective about the kids who get cut and then, wanting nothing more than to participate in an activity that brings them not only joy but health and wellness, have to give it up. They are now caused to sit at home on their phones instead to going to practice where they'd rather be.

“My God, I remember that day,” the parent of an athlete who was cut from the soccer team in tenth grade said. “All his life he'd been going to practice three or four days a week, watching on TV. He'd wear the jerseys of favorite players to school. It wasn't his only thing but it was a big part of his identity. And then one day it just ended. The coach said, ‘You were really close,’ but that didn't really change anything. He wouldn't wear his jerseys to school. There's no youth league to play in anymore when everyone else is playing school ball. Suddenly, he wasn't a soccer player anymore.”

What if there was another team—a developmental team that practiced once or twice a week? What if the varsity coach came by for 20 minutes to run a drill or watch a scrimmage and tell the players there he or she thought they were doing well and hoped they'd all try out again next year? What if there were a few no-cut sports? (We know one school where the cross-country team does not cut from the JV.)

JV teams and freshman teams are disappearing, both at the K–12 and the collegiate level. Even when there are such teams, younger, more “promising,” athletes often play up in age and the eleventh grader who has diligently come to practice every day for years and been a committed teammate and whose only crime is that she'd probably just warm the bench on varsity as a senior loses her spot. The message is this: If you're just a committed and dedicated team member, there's not really a place for you.

Winning in school sports is not irrelevant. We understand that. Seeking to win is a big part of what makes the experience of playing valuable. It's what causes us to have to cooperate and collaborate and subsume our own personal desire (I want to score) to the goals of the endeavor (but it's better to pass). That's a powerful learning experience. The lessons of striving to achieve a goal you care about are real and that's why young people love sports. We're not arguing “winning doesn't matter; it's all about participation.” We are saying it’s not always either/or.

Friedman and company doubled the length of tryouts so the kids who didn't make it got to be a part of things for much longer. And then they tried make “event” roles for them. “We built some committees to help sell concessions, take tickets, provide crowd control, and so on. They turned into a booster club/supporters of sorts. Organically, we ended up with a section of our gym reserved for them.” That doesn't have to be everybody's solution. But given what we know about the immense benefits of being on a team in terms of well-being and belonging, maybe we should be thinking more intentionally about those last few kids we cut. There's surely space for more young people who want to be a part of something and are willing to do the work.

For their part, Nashville Classical's teams didn't win much. To be fair, they're a tiny school and it was their first year with eighth graders, but, Freidman notes, when they held tryouts recently, “twice as many students showed up to participate. So, I think we won where it counts.”

LEADERSHIP FOR COMMUNITY AND BELONGING

Part of the story of the extracurricular redesign at Nashville Classical was the outcome and part of it was the process. The school decided that redesigning a key aspect of its programming through the lens of belonging and connection warranted a team of people from across levels and departments. The team “owned” the issue—one that doesn't ordinarily get a cross-functional administrative team—and had broad latitude to think about it in new ways. Not every idea they came up with was accepted but they were asked to do what you might call strategic design work. They planned out a vision carefully and intentionally in advance. And they met regularly to manage and prioritize it throughout the year.

Making things like connection and belonging—and culture more broadly—a focus of school life means engaging systematically in this kind of strategic design, often for topics that don't typically get that level of analysis. Doing that requires sustained reflection and focus. So it also requires different leadership decisions.

Start with a Clear Model

Charlie and company started with a conversation about what they believed to be true and important about extracurriculars, about why, as a school, they did those things in the first place. “When a group of people come together for a common cause they should start by thinking not about what they do, nor how they do it—but why,” Simon Sinek writes in Start with Why. “We are drawn to leaders and organizations that are good at communicating what they believe. Their ability to make us feel like we belong, to make us feel special, safe and not alone is part of what gives them the ability to inspire us.” Being clear about purpose is an effective tool to build belonging among staff as well, it turns out.

The team at Nashville Classical boiled down the why for extracurriculars into three core principles. They refined, discussed, and agreed to them. Then they mapped things out from there: If we truly believed these things, what would extracurriculars look like?

The work of most schools outside the classroom hasn't historically gotten this level of analysis. On the academic side, it would be expected for a school administrative team to meet to plan what assessments they would give, what grading would look like, and what curricula they'd choose. They'd meet to look at data on how things were going, drilling down to ask which kids in the fifth grade couldn't multiply fractions and whose reading words per minute was lagging. They'd discuss responses to data, both individual (tutoring for Sarah) and systematic (a tutoring system; more reading aloud in class). And then they'd circle back to assess the results. Were tutoring systems working? Why or why not?

But too often the cultural part of school-building gets far less of this sort of analysis. We leave the plan or its implementation to chance and good intentions. We don't constantly meet to ask how it's going and make small tweaks. Maybe we choose the virtues or values we want the school to instill, and we ask teachers to stress them whenever they can. Maybe there's an advisory when we ask teachers to talk about things like virtues but we leave them to plan (or not plan) for that as they wish. The procedures and expectations we want for public spaces—how we'll enter the building; how we'll sit in the auditorium for morning meeting—we leave to the mercy of whatever norm emerges.

Is it worth noting that the culture that exists in Denarius's math classroom began with him thinking through a series of granular, detailed questions about his own vision for the classroom? Something like: If my fundamental belief is that each young person in my classroom is capable of excellence; if I believe that caring involves not just pushing each of my students to give their individual best every day but also pushing them to do their part to build a mutual culture where they bring the best out of each other—if I truly believe those things, what should my classroom then look like? How should students sit? How should they talk to each other? What should they do when someone else is talking? What should they do when I ask them a question and they are not sure of the answer?

Is it worth noting that all of the answers and the systems he has subsequently built around them are subject to constant reflection and evolution?2

Arrival works the way it does at Shannon Benson's school because the school started with why. We want students to feel seen and known and welcomed individually and we want to gently remind them that they are entering a school where expectations are a little higher than in other places in the world.

Then they planned out the details of what that would look like: students would be expected to greet the adult at the door as they entered. They'd shake hands or perhaps high-five (generally at the discretion of the staff member) and have a brief moment of eye contact. There would be two staff members present so if one was drawn away (a student needing something; an opportunity to check in with a parent at their car), the ritual would remain intact. Some of these details they planned from the outset; some of them they figured out as they went along by having regular meetings to discuss aspects of the school's culture: How's arrival going? What's working well? What could be better? Where are the opportunities?

Breakfast at Stacey Shells Harvey's school works because there's a procedure for who will write the questions (rotating schedule), who will review them, and how discussion will be fostered. But again there was a constant feedback loop. A few questions teachers initially wrote were not ideal, so the school realized they needed to add an administrator review of questions just to be sure. And though teachers had been trained to use Habits of Discussion (they used it in their academic classes), there were reminders and tweaks for the new setting that emerged from asking, How's breakfast going? What's working well? What could be better? Where are the opportunities?

The themes here are:

- A culture needs a blueprint, a clear description of what we want it to be and why. Building culture can't just be about ensuring that certain counterproductive things don't happen; there needs to be a detailed vision of what should happen.

- Even once it's planned and installed, it will need a feedback loop of regular discussion and reflection.

- To do that you need a consistent team and a regular time to meet and ask, over and over, how's it going?

Charlie's extracurricular team met regularly. They planned the changes they wanted and then once implementation started, they suggested adaptations—tweaks for this year, notes on bigger changes for next year. In Switch: How to Change Things When Change Is Hard, Chip and Dan Heath describe a common logical fallacy: we assume the size of a solution must match the size of the problem. But in fact this is not true. I could have a big problem and solve it with a tiny solution. In fact this happens all the time in schools. In a complex environment, a small change can initiate a cascade of subsequent changes.

Jen Brimming and her colleagues found this at Marine Academy in Plymouth, England. The culture of classroom and the school overall felt too quiet, low energy. Teachers weren't sure students were enthusiastic about learning. But introduce two tiny tools, Turn and Talk and Call and Response and, as you saw in the videos, suddenly everything changes. Students are engaged and enthusiastic and the classrooms come to life.

“Big problems are rarely solved with commensurately big solutions,” the Heaths write. “Instead they are most often solved by a sequence of small solutions, sometimes over weeks, sometimes over decades.”

From our point of view, that's the trick. Map a plan and then keep meeting to examine discuss and assess. Constantly seek small improvement every week. And that may sound simple but what it implies is that organizations' structures need to be different.

A CULTURE OF CONNECTION AND BELONGING WILL REQUIRE CONSTANT ATTENTION

Before Stacey Shells Harvey led ReGeneration Schools, she was a principal at Rochester Prep in Rochester, New York, and one of the things she took very seriously was culture. She was intensely focused on ensuring academic excellence for her students but also wanted a vibrant culture that fostered belonging. So she had two learnership groups that she met with weekly. One focused on academics. It was made up of the heads of each subject, who met weekly to discuss curriculum, instruction, and assessment. They looked at data and discussed tutoring or extra support for some students. It was a team. They shared the work of implementation and held one another accountable.

But she did the same with a culture team, which included a different group of staff: grade-level leads for each of the four grades in the school (fifth through eighth) as well as the dean of students. They met weekly too, to discuss all the things that build culture: the general feel of classrooms or the lunchroom from a cultural point of view, which students might be struggling and acting out, what visual culture in the hallways should look like, and especially what they would talk about at all-school “meeting” that week. This required planning because Harvey's standards were high! There had to be sharp-looking slides, and if there was music, it had to be right. The presentation had to be rehearsed. These things required collaborative leadership, constant teamwork, focus, and follow-through.

A “culture team” of dedicated people responsible for different aspects of the school but who consistently met to talk about things like belonging and connection and community would be an ideal setting to talk one week about arrival and the next about breakfast and the next about hallways—all of the mechanisms we describe in Chapter 4, plus others of your own devising.

PREPARING FOR WHEN IT BREAKS DOWN

No matter how well we design culture, no matter how strong the group norms, there will be breakdowns in the behavior of individual students. There will be students who engage in negative behavior or break the rules, particularly when they are teenagers, because teenagers are especially prone to testing limits and especially likely not to fully consider the consequences of their actions.

This is not a judgment about any particular group of young people—most of us broke rules at times when we were young. It does not express a lack of faith, belief, or trust in them. It expresses an understanding of the world they (and we) live in, where on one hand some people will be kind, thoughtful, and helpful and other people will be careless, thoughtless, or even cruel, and the institutions we build try to help more people do the former and fewer people do the latter. The fact that every society on earth has both norms for how people should aspire to behave and laws defining what happens when they don't is not the result of arbitrary convention but the outcome of vast accrued experience with human nature.

In schools, our job is to create a climate where the rules are fair, and their benefits are significant and evident to as many people as possible. Our job is to create a climate where shared norms of positive and constructive behavior are so well established that people want to give their best and are less likely to consider negative behavior. And then, despite that, we have to be ready for breakdowns—times when norms or rules are broken with adverse consequences for both rule-breakers and others in the community. When that happens we have to be prepared to teach young people alternatives to thoughtless, cruel, or selfish behaviors, ready to help them glimpse the best version of themselves and to understand how much they have to gain from moving closer to that version.

If we know this will be required of us, we should be prepared for it, but our strong sense is that this is often not the case. Having a plan to respond effectively to breakdowns (counterproductive behavior that disrupts the learning environment and erodes culture) is a critical aspect of building an environment where students feel safe, supported, and connected. It is hard to feel a strong sense of belonging in a place where you feel anxiety in the hallways and the bathrooms, where you sense that some number of your peers are snickering at your struggle or scoffing at your aspirations.

Schools, this is to say, owe it to students—both those who can do better and those who suffer the consequences—to have a clear plan around behavior breakdowns: Whose job is it to respond? What's the plan for how they'll do that?

We think that like any complex and challenging work, it needs both a champion and a team—a lead person to own it and a group of people who meet regularly to assess the process and ask how it's going, what's working well, what could be better, and where are the opportunities.

We call the role of leading the work of addressing disruptive behavior in schools the ‘dean of students’ role. Other people call it other things. In the UK it's often called pastoral. In many schools in the US there is no name for it, and this can sometimes reflect a lack of clarity about what should happen when a student significantly disrupts the learning environment or breaks a rule that protects the safety or learning of classmates. Sometimes that student is sent to an assistant principal or the principal herself, and sometimes to another teacher, or sometimes to a social worker. Sometimes the student isn't sent anywhere at all.

We'd argue the word “sometimes” isn't a very good one. If there isn't an “always”—a consistent process for how it's supposed to work—things will fall apart. The most challenging kids—the ones already pressing up against the systems in the school—will quickly exploit the ambiguity. We won't know what happened after this morning. We won't know that what happened in Mrs. J's class this morning also happened in Mr. P's class yesterday. And we won't be able to put resources in a consistent location so that when negative behavior happens we can ensure that the person who responds will have the resources to do what is supposed to be our core work: teach.

The dean’s role is often the hardest role in the school (we have all done it so we speak from experience!) and a common problem is that when there is such a person they are often simply told to “deal with” behavior. They rarely get serious training and support. The result is an overreliance on consequences. Don't get us wrong; consequences for poor behavior are often part of the process of learning, especially if they are combined with teaching and behavior change. But they are also simpler to use and easier to deliver than teaching, and there's an attraction in that they create instant proof that a school has “done something.”

And it's often important to do something. Censure and limit setting matter. Consequences can help with learning and behavior change. But we all know that they don't help automatically, and they can sometimes make behavior worse. We know that “doing something” can be a short-term fix and does not result in students learning how to change. And it is least likely to result in learning among the students who need to change most.

Consequences are an important tool for schools to design and use wisely—that's also technical and demanding work—but they are not teaching. And teaching is, in the end, what schools are tasked with. So the question is, what tools are available beyond (or in addition to) consequences to shift responses to student behavioral breakdowns so they focus more on teaching?

Before we discuss that, let us pause for a moment to answer the question: Is this really that big a deal? Is failure to plan for and design systems of response to behavior breakdowns really a major problem in schools? Aren't there too many suspensions already? Isn't this why skeptics have invented the red herring term “carceral” to describe some schools?

The argument of this section so far has been that culture needs intentional planning and management of the sort that Charlie Friedman and company brought to their study of extracurricular programs, and that this gap is most glaring in the plan for behavior breakdowns. The general lack of clarity about the process of what happens and why, based on a set of core beliefs, planned out in detail and constantly reflected on, is a major contributor to an environment in which the conditions necessary to learning and socioemotional flourishing do not exist for a large number of students.

PREPARING FOR BREAKDOWN, PART ONE: TO TEACH WELL YOU NEED A CURRICULUM

Our belief about the dean's role, and about responding to breakdowns, is that the school's primary response should be to teach. This does not preclude consequences, but it would ideally both supplement them and improve them by making them more effective in changing behavior. A deep and profound reflection where you write extensively about the ways to use social media positively, study examples and then use the resulting insights to reflect on your own actions can supplement a consequence for injurious online behavior. Done well it can serve as the consequence in and of itself in some cases.

This points us to a key observation. If we expect people in the dean's role to teach in response to breakdowns, one of the first things they will need is a curriculum, a set of carefully designed and planned lessons to structure and enrich what they teach. Having a curriculum not only increases lesson quality but it saves labor. It means not having to invent a “lesson” in response to each new situation on the spur of the moment (and while managing an often emotional young person). If the choice is between teaching by the seat of your pants when you are busy and not prepared on one hand, and giving a consequence that requires little reflection but probably results in little learning on the other, the rational person will often choose the latter. And even if the latter is an appropriate response, it will be far more successful if combined with the former.

In looking at the role of the “dean of students” (or whatever name you give it), what we are describing is a job that is “predictably unpredictable.” A dean knows that some young person in the building will make a poor decision on social media, or will behave in a way that is rude and demeaning to peers or a teacher, or will copy someone else's work. They know these things will happen because they are the sorts of things that always happen when a large group of young people learn to make their way in the world and test a variety of strategies to figure out who they want to be in different contexts. That part is entirely predictable. The dean just doesn't know which students, when, and where. That part is unpredictable.

But if much of the behavior deans seek to address is predictable, the opportunity is in advance preparation.

Consider something as simple as writing a letter of apology to another student—let's say after having deliberately thrown a basketball at them during a game of knockout gone wrong. What would you get if you asked a representative sample of students to write such a letter?

You would get immense variety. Some young people would write sincere letters using direct and accountable language. You'd notice sentences that began with the word I to describe what they'd done. (“I apologize for throwing the basketball at you.” Or “I threw a basketball at you today and I want to apologize for that.”)

They'd demonstrate their awareness of how their behavior made the other person feel. (“I know it must have hurt, and it was probably embarrassing too, with everyone watching.”) Some might affirm their appreciation and respect for the other person. (“I want you to know that I think of you as my friend.”) Some might express a desire to make amends. (“Maybe we could play knockout again at recess tomorrow.”)

The four of us have all read a version of a letter like that, where a student's ability to own their actions and rebuild trust with a peer has earned our respect such that they leave our office having raised our appreciation of their character and maturity despite the initial mistake.

More important than our own esteem, though, is that such a young person is far more likely to build successful and meaningful relationships as a result of the integrity, compassion, and empathy they are able to express. For this reason, we wish that every young person had the skill of writing a genuine apology.

But of course they don't.

In addition to the ideal apology letter, you would get, in your representative sample, letters from young people that were vague and merely “apologized” without apologizing for something. (“Jason, I am sorry about what happened on the playground. David.”)

You would get letters that failed to take responsibility (“I'm sorry you got hit by the basketball”). You would get letters that subtly (or not so subtly) blamed the recipient. (“Sometimes you act like you think you're better than me, but that's no excuse for throwing a basketball.”) You would get letters that suggested the writer was unlikely to rebuild the relationship with the recipient going forward. (“Next time I will just try harder to ignore you.”)

If you are the one who deals with the young person who has thrown the basketball—and maybe the thrower's erstwhile friend has been sent to you as well—you have a lot of work in front of you if your goal is to teach the art of apology and the reflection and emotional self-regulation that come with it.

You are going to be spending a lot of time talking about what makes a good apology and why those things are important. You are going to be spending some time drafting and redrafting the letters in question. Or you are going to be signing off on some poor apology letters that don't accomplish much and tacitly send the message that making amends is a process easily sidestepped after having done someone wrong.

You will probably be engaged in this task of teaching two potentially emotional young people how to make a proper apology while you are doing other things. Perhaps there are other students in your office. Perhaps one of them is crying. Perhaps you have to go check on a student to make sure she's doing okay today. Perhaps a parent has just shown up to ask for his daughter's cell phone, which you confiscated yesterday. (Good job, by the way; see Chapter 2.)

Having a curriculum would mean having a lesson plan, or a series of lesson plans, about apologizing at the ready. You'd walk to your file cabinet and pull it out. It would be rigorous and challenging but also interesting. Maybe it would start with a general reflection on apologies, something like this:

We all make mistakes, but how you respond to mistakes can make a huge difference in how others perceive you and the situation you were in together. Simply apologizing by saying “I'm sorry” is often a helpful first step in those moments.

When you apologize, you're telling someone that you're sorry for the hurt you caused, even if you didn't do it on purpose. You are showing that you have the maturity to understand their point of view. Apologizing also often makes you feel better because you are clearly trying to put things right. That again is a sign of maturity.

When you say, “I'm sorry,” it helps people refocus their attention away from identifying who was to blame. Now you can be working together to make things better. It can help you maintain—and even strengthen—your rapport with others.

Stop and Jot: What are some of the benefits of apologizing when you've done something wrong?

Then maybe it would ask students to look at some samples. Like this:

An effective apology should be honest, direct, and acknowledge that you did something that negatively impacted others. It should not cast blame on someone else or try to provide justification for your actions.

“I'm sorry about what I said to you.”

“I'm sorry I lost your book.”

“I shouldn't have called you a name. I'm sorry.”

“I'm sorry I hurt your feelings.”

“I'm sorry I yelled at you.”

“I'm really sorry I hit you when I was mad. That was wrong. I won't do it anymore.”

Stop and Jot: Why are these apologies effective? What are some things they share in common?

Then perhaps it would ask them to reflect in writing on apologies they've experienced in their own lives, like this:

Answer the following questions in complete sentences.

- Describe a time when someone apologized to you. How did it make you feel? Why?

- When was the last time you apologized to someone else? Why did you apologize, and how did you feel afterward?

- When do you find it hardest to apologize to others? Using what you learned from the first reflection, what could you say to motivate yourself to apologize?

Then perhaps they'd be asked to apply their growing knowledge of apologies to situations they might face in the future. Like this:

Explain what you might do and say to apologize in these situations:

- You accidently bump into a classmate in the hallway when you are not watching where you're going. They drop all their things, which scatter in the crowded hallway. You mutter, “Oh, sorry,” but you don't stop to help. You see him in class that afternoon.

- You promised your mom you would be home on time, but you did not make it home on time because you were talking with a friend and missed the first bus. She'd made dinner for you and it was cold. Now she is watching TV by herself on the couch.

- You were mad about something and were sulking in class. You didn't participate at all and were looking out the window. Then you put your head down on your desk and said, “This is so boring.” You said it to a friend, but you know the teacher heard you. You're in the hallway just before dismissal and see her standing outside her classroom talking to another teacher.

Then perhaps your student would write their letter of apology. Perhaps you'd provide them with a list of do's and don'ts as a helpful reminder. If they were struggling, you'd have a sample letter they could read and annotate.

As with any good lesson, you'd want to end with an assessment, an Exit Ticket that would allow you to see what your students understood differently now and maybe even how they might use it to respond differently to the situation they'd initially struggled with.

You could use some or all of these tools depending on the situation. Maybe your student who has thrown the basketball gets it immediately and is sincere and ready to write and doesn't need a lot of further analysis. But maybe that student is just going through the motions and doesn't really think he or she should apologize. In that case the student would then get different activities from the sequence of possible learning tasks you had available. Or maybe both participants in the incident have been sent to you and each owes the other an apology, but they are in different states of readiness and reflection. In that case there would ideally be different tasks for each of the young people involved.

Ideally they'd work hard at the tasks—so hard, in fact, that further consequences wouldn't really be necessary. You'd simply make a copy to send home to their parents so they were aware of the situation and the work their child has done in self-reflection. Perhaps you'd ask the child to have the parents sign and return the letter. Then you'd put the student's work in a file. You'd never see one of them in your office again, but the other one would be involved in a similar incident two weeks later. You begin then by taking out what the student wrote the first time around and asking them to reflect on how the two times are connected and why they were in your office again.

Really teaching about behavior requires content and preparation, this is to say. If we're serious about responding to breakdowns with teaching, this is a gap we'll have to close. Teaching in any setting won't happen without meaningful things to teach, organized in a useful way. That means a curriculum, which in turn means planning and resources: perhaps a team of people, perhaps a few weeks of paid time during the summer to prepare lessons, perhaps the addition of a team member on staff whose job is to develop activities in response to incidents and then organize and file them so they can be reused and adapted.

It might seem like a lot, but with young people more and more likely to struggle at the skills required in challenging social situations, it is more important than ever to do the work in advance that allows us to teach in response to misbehavior.

LESSONS FROM THE FIELD

As it happens our team recognized the need for a dean of students' curriculum in 20184 and have developed a pilot version5 with 70 or so lessons targeted to middle school students6 and focused on a wide range of topics that cause students to show up at the dean of students' door. We've been piloting it for a few years and think the results are promising.

Here, for example, is a student's response during our version of the apology exercise described above:

And here is a typical piece of student work a young woman did before reflecting on her own poor choice on social media. (Lessons typically end with a series of reflections along the theme of “In retrospect what could you have done differently in this situation?” and “What are you going to do differently next time?”)

As we've piloted our version, we've found in fact that it can be used in three ways. First, it can be used to teach values and virtues in advance in an advisory setting or a homeroom, as described in Chapter 4.

Here's an excerpt from our lesson on gratitude, for example. It's as effective in proactive teaching of virtues as it is in reacting to specific situations where students struggle with behaviors.

| Application of Terms |

|

Second, it can be used in what we'd describe as therapeutic settings—small group pullouts for students who have specific skill gaps such as managing anger or responding to peer pressure. Like proactive teaching, it is designed to build skill and head off potential incidents. The difference is that it would be used with individuals or targeted groups of students who might be especially likely to have issues.

Finally, we've found it useful in the setting we've described here: responding to breakdowns. Users have noted that the written work students have done is also useful in sharing with teachers whose classes their behavior may have disrupted. In many cases a challenge schools face is demonstrating to that teacher that “something” has happened and “steps have been taken.” A student may have been working hard reflecting on an incident but a teacher may not know that. Their perception may be, “She waltzed back into class an hour later as if nothing had happened.” This is a recipe for further tension. Now a dean (or the student herself) can share the work she's done with relevant teachers so they understand and appreciate the level of response.

Schools have also appreciated one of the themes of the curriculum: its emphasis on replacement behaviors. It's not enough to tell a young person not to do something. Effective intervention means helping them identify and develop the ability to use an alternative, what we mean by a replacement behavior. It's hard to think of a replacement behavior on the spur of the moment, which is another benefit of a curriculum.

We also added an Exit Ticket to all of our lessons. This ensured that deans would be able to assess what students understood differently as a result of their work together. Making Exit Tickets separate from the lessons allowed them to serve both responsive and proactive purposes. That is, if we were using a lesson therapeutically with a group of students we were trying to keep from having incidents because we knew them to be high risk, we wouldn't want to ask, “How does all of this apply to what brought you to my office today?” But we would also want to ask that if we were reacting to such an incident.

| Name: ________________ | Date: ________________ |

| Exit Ticket | |

|

Directions: Answer the following questions based on what you just learned.

| |

We mention these things not to trumpet our own work—it's a work in progress and will require constant attention and improvement—but so you have a model in mapping your course if you develop materials, lessons, and what ultimately becomes a curriculum designed to address breakdowns. (That said, if you'd like to know more about ours, you can check it out here: https://teachlikeachampion.com/dean-of-students-curriculum/.)

PREPARING FOR BREAKDOWN, PART 2: TEACHERS NEED TRAINING

If we expect people in the dean's role to teach in response to breakdowns, the second thing they will need is a clear model for what teaching in that setting should look like, ideally one that draws on our knowledge of effective teaching in the classroom.

We'd want to have a high Ratio during lessons, for example. For those not familiar with that terminology,7 it means we'd want students to do the lion's share of the cognitive work. “Memory is the residue of thought,” the cognitive psychologist Daniel Willingham says. Thinking hard results in learning. Being in the dean's office should mean doing a lot of thinking, reading and writing, just like anywhere else in school where we want to maximize learning.

And at the end of a learning cycle, we'd want to check for understanding—that is, make sure of what the learner learned.

We set out to build a model by taking the video cameras we usually train on teachers and training them on deans instead. We followed them around all day and made note of what they did. We then identified principles for what the teaching parts of the work should look like, one set for Private Deaning and one for Public Deaning.

Private Deaning refers to one-on-one conversations and interactions with students in which we discuss their behavioral choices and their outcomes and attempt to teach them the most productive responses or strongest robust skills.

Public Deaning is the equally important role that deans play of circulating throughout the building and interacting with students and others to reinforce positive values and set strong norms.

PRIVATE DEANING IN SIX STEPS

Here are the principles for successful teaching that we discuss with deans during our training workshops, expressed in six steps.

Private Deaning, Step One: Assess readiness. Any conversation starts with a viable connection. Make sure a student is able to listen and discuss behavioral choices in a mutually respectful and productive manner. Remaining calm and using a slow, quiet voice can help. So can stressing purpose over power, something like “I want to hear what you say happened and I promise I will listen carefully,” or “I want to hear what you say happened and I promise I will listen carefully but you will have to listen as well and speak to me in the same calm voice I am using with you.” If you don't have those things, don't proceed.

Private Deaning, Step Two: Gather information. Make sure you know the details of what happened from the teacher, from other adults, and other students. Get it calmly and clearly and ask follow-up questions if necessary. “I know you said she was teasing Michaela. Can you just be a bit more specific so I can be specific with her and, if necessary, with her parents? What exactly did she do and say?” Ideally, ask them to write down their version of events so you can refer to it carefully. This will also slow them down and give them a way to process potential frustration.

Private Deaning, Step Three: Teach. Try to build students' knowledge. “We're going to talk about your impulse control in the classroom. I want to first make sure you know what an impulse is and what it means to control your impulses. I might even tell you a bit about a region of the brain called the amygdala.”

Writing is a powerful tool for thinking and reflecting. If there's any doubt, have the student write to describe the incident. This will cause them to have to reflect on it, think more deeply, and articulate a response in writing. Ask clarifying questions and potentially ask them to revise what they've written so they get things down in a version of events that you can refer back to later. Ask follow-up questions to try to get very specific answers. “What do you mean by ‘she was rude’? When you say she was disrespectful to you, what did she do exactly? How do you know she meant it that way?”

You could also ask them to write in response: “Now I'm going to tell you the story from another perspective. I want you to take notes on what Mrs. Hopkins said because I'm going to ask you to respond.”

If there's no debate about what happened, have the student focus on writing and thinking about what they can learn from the situation. If possible, help them identify a replacement behavior and how they might have used it: “David, the science here is pretty clear. If you can slow yourself down by even a second, you increase the chances that you won't do something impulsive. That means if you can simply make yourself take a deep breath when you find yourself getting upset, it can make a big difference.”

Check for understanding at the end. Consider an apology or give a consequence to make amends.

Private Deaning, Step Four: Build them up. Remind students that while you do not approve of their behavior in this instance, you believe in them, and that making mistakes is common as people learn and grow. Talk aspirations to connect the behavior to goals. “I know you said you want to be a fire fighter. I want you to think for a minute why you will be a better fire fighter someday if you are able to control your impulses.” One purpose of a consequence is to make amends, so adults should not hold a grudge. You should make it clear to a student that they are back in good stead with you.

Private Deaning, Step Five: Close the loop. Inform the teacher, the parent, and other staff (if appropriate) of what the students worked on. If the incident involved being removed from a classroom, transfer authority back to the teacher by allowing the teacher to accept the student back and facilitating that conversation. “David has worked really hard for almost an hour now at reflecting on his behavior toward his peers and he's written an apology to Whitney. Are you ready to have him return? (Have a conversation ahead of time with the teacher wherein you address any lingering issues so that conversation with the student does not take unexpected turns.)

Private Deaning, Step Six: Follow up. Ask the student how things went at the end of the day. Ask the teacher as well. Make sure the student knows you asked the teacher! Let the family know you followed up and let them know how things went, especially if there was an improvement! This demonstrates that your interest is in the student and their long-term success, as opposed to merely having a narrow interest in resolving a single event. It also helps the student succeed by making it clear that you are looking for and will follow up to see long-term behavior change.

As the video of Jami Dean shows, it's critical that individuals who deal with students after behavior breakdowns not be tied to their desks. The job should be to shape and speak for the culture in the school and to build right and multi-acted relationships with students. It's important not to act like a B-movie villain, whose entry into the room causes everyone to know something bad is about to happen. Deans should celebrate positive culture too. In so doing they make themselves more able to connect with and teach students when they err. We call this part of the work Public Deaning and it too requires clarity around purpose, careful planning, and constant reflection.

Here are the principles:

Be visible: Cycle through classrooms, and every part of the school, constantly interacting with students, showing appreciation for positive engagement, and building connections. This is also an opportunity to teach students how to be productive and positive in class before things go wrong.

Gather data: One of the best reasons to be a constant presence in classrooms is to gather data. You might look for such information as: Which classrooms' culture seems strongest and most vibrant? These classrooms are a great place to bring a struggling teacher. You might stand in the back and observe, perhaps guiding the teacher's eyes: see how crisp and clear the teacher's directions are (no extraneous words). See how the teacher smiles when reminding students of the expectations? That's a great way to remind our kiddos that the rules are there because we care about them. You could also spot the teachers whose classrooms are a bit rocky. Perhaps you could model a few things for them. If you don't feel comfortable with that, you can always learn about which kids seem to struggle to focus, which ones seem hugely engaged in one class but not another, and which seem to look at you as you enter as if they are hoping for a connection with an adult.

Embody values: Everywhere you go, you have the opportunity to speak for the school's values. This can mean looking out for moments when virtues are exemplified and calling them out. “Thank you for helping James wipe down the table after lunch. You're always helping out, Jordan.” It means you can make small corrections and find opportunities to teach social skills. “You're really shouting at Josefa right now. I know you're friends; there's no reason you couldn't tell her to pick up her stuff with a bit more warmth in your voice. Like this …” You can also model yourself. Even small things, like always saying please, thank you, and good morning. Small courtesies, as we learned in Chapter 1, are key belonging signals. In fact, you could literally be a walking, talking, belonging signal.

Build relationships: That's critical to all of the principles we've described. But to make it easier, we've got a list of simple actions and phrases to help students feel seen, valued, safe, and connected:

- Nonverbals

- Smile, point, wink, send magic.

- Use high five/fist bumps/warm hand on shoulder.

- Make Students Feel Known

- “What are you reading?”

- Leave notes or smiley face on desk or seatwork.

- Follow up to ask about something they did or told you about previously. “How'd that science project turn out?”

- Shout out students at community meetings or with their teacher. “Ms. Jenkins, you should see Jabari's notes back here!”

- Talk to students at lunch/dismissal, especially about academics.

- Use or even invent names/nicknames.

- Stress Values and Virtues

- “I'm proud of the fact that you …”

- “Thank you for your hard work on….”

- “Nice job on _______. Keep it up.”

- “That was impressive when …”

- Recognize student work.

- Positive calls and texts home—with a picture is great!

CLOSING: DEANING FOR CONNECTION AND BELONGING

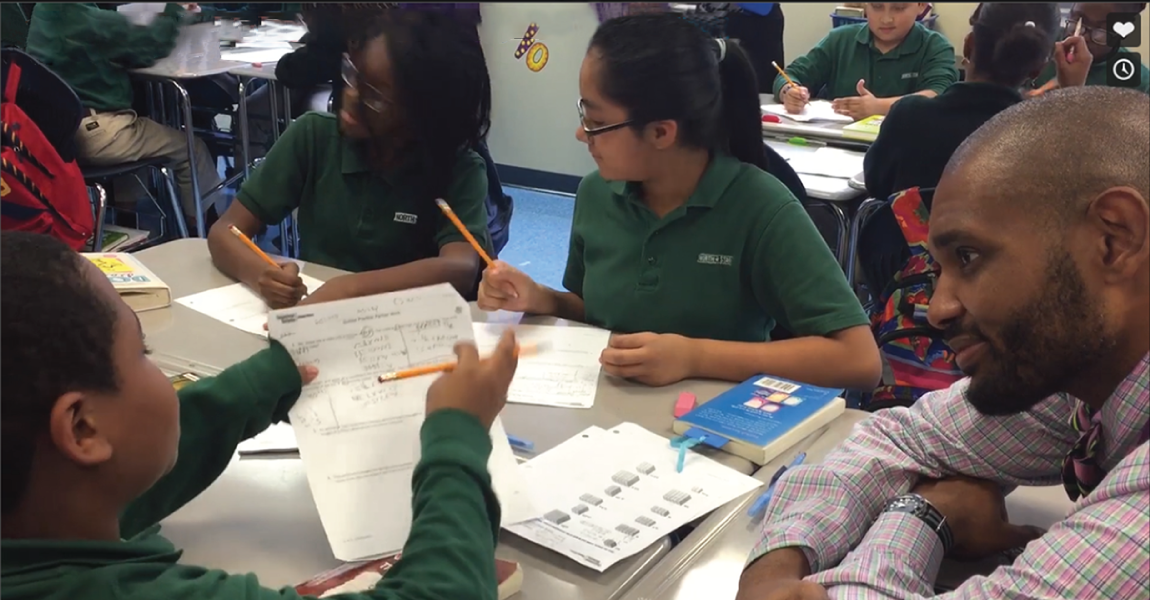

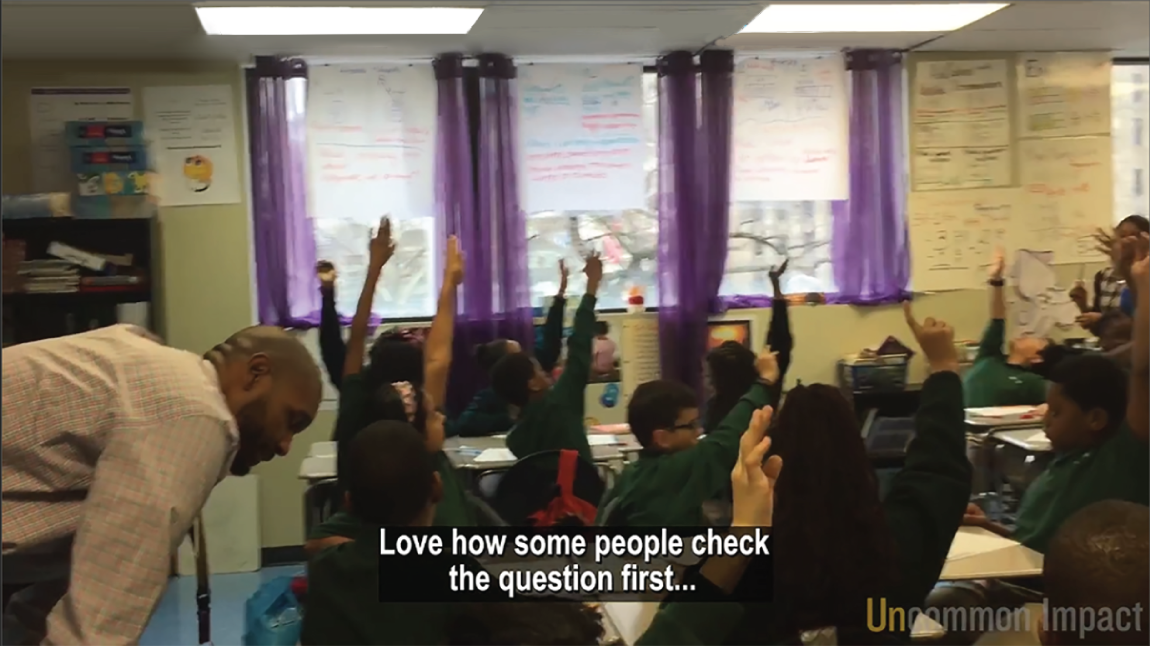

In this series of images, we see Jamal McCullough, dean of students at North Star Academy Downtown Middle School in Newark, New Jersey, illustrating a point that we've made multiple times—the classroom is the primary place where a culture of connection and belonging is cultivated. As such, schools must organize their personnel and resources to align with this truth.

In his role as dean of students, Jamal is responsible for designing, embodying, and upholding all aspects of his school's culture. Anyone who's held this role or a similar one knows how complex it is, encompassing everything from teaching replacement behaviors, to data collection, communicating with parents and other stakeholders, filing reports, and monitoring schoolwide transitions. Jamal can usually be doing all of those things, but he tries to prioritize time in classrooms above all else because there is no more important space for a school to cultivate a culture of connection and belonging.

On this particular day Jamal is observing classrooms, partly as a matter of habit and partly to follow up with a student who was sent to his office the day before. Each of these images tells a story of connection and belonging.

In the first image, we see Jamal sitting with students. He's been listening intently as a student explains how he arrived at an answer. He's very much in role here, pretending to be a sort of senior, most experienced, role model student.

Now the teacher has sent students into a Turn and Talk, and with an odd number of students Jamal has eagerly grabbed the opportunity to be partners with the student in the foreground. Consider the message this student is receiving: The dean sees me and cares about my work. In fact, think about how many students never get to interact with the dean until they've been sent to his or her office. This student gets to spend time with the dean when all is going well, as opposed to when they might have made a poor choice. This matters for establishing a school community where students feel connection and belonging.

In the second image, Jamal is sitting with a group of students and the teacher has just asked a question. Jamal's hand shoots right up, modeling how to show positive engagement in class in the way one raises one's hand. The teacher playfully acknowledges Jamal in this moment saying, “I see Dean McCullough knows the answer.” It's a delightful moment, one full of belonging and connection cues, for both adults and students. The teacher receives signals of support, alliance, and trust. There's a partnership here and Jamal wants her to know he's there to support her, not to check and see if she can manage her classroom. Students can feel this too. The partnership they see between dean and teacher is a mirror for how people work together within the community, and communicates how invested they are in the success of students.

In the final image, we see Jamal crouching down and holding a quiet conversation with a student who was sent to his office the day before. To encourage him, he says, “You're a student and this is where the magic is happening, right in this classroom, alright?” Then he asks, “Do you need anything?”. Message: Jamal's goal yesterday was not to give a consequence or “process” him in the dean's office. It was to help him learn. The follow-up visit communicates that this—successful engagement in class—is his purpose.

The cues for connection and belonging in this short exchange are also important. The message the student receives is: there are high expectations here but I'm going to support you in meeting them. There's nothing more important than you being here and I'm here to make sure you receive the education you deserve.

Observing Jamal's work in the classroom affords us an opportunity to close by observing that deans of students are not always a priority in schools. Some don't have them. Some have just one who struggles to leave his or her office. If schools are serious about building purposeful cultures grounded in connection and belonging, they must align resources, especially key personnel to make that a reality. Building connection and belonging means recognizing that schools are first and foremost cultures. If that's true, then they need a person—a team of people—who are its champions, who wake up every day thinking about building and sustaining it to ensure that something real and meaningful and rigorous exists for all students and to make sure that all students get the support they need to connect to it.

Notes

- 1. The group consisted of Marisa Frank, Xavier Shackelford, Hasan Clayton, Trent Carlson, Kristin Barnhart, Marina Carlucci, and Jasmine Parker. Charlie wishes to thank them deeply and note for the record that “the work and wisdom was all theirs.”

- 2. In one of the last edits of the book, Denarius observed how his preferred language to cue tracking had evolved so that he was using the phrase “Let's put our eyes on …” more and more.

- 3. https://www.uncf.org/wp-content/uploads/reports/Advocacy_ASATTBro_4-18F_Digital.pdf

- 4. Thank you to the Kern Family Foundation for supporting the development of this curriculum.

- 5. You can read more about it here: https://teachlikeachampion.com/dean-of-students-curriculum/

- 6. We hope to add high school and perhaps elementary school as soon as possible.

- 7. See Teach Like a Champion 3.0.

- 8. Out of respect for the student's privacy, we have shared only audio instead of video and not named the school or the staff member. We are nonetheless grateful to them for sharing and appreciative of their thoughtful work with young people.