Chapter 6

Balancing Assets against Liabilities and Equity

In This Chapter

![]() Defining assets, liabilities, and equity

Defining assets, liabilities, and equity

![]() Exploring the basics of balance sheets

Exploring the basics of balance sheets

![]() Reviewing assets

Reviewing assets

![]() Understanding liabilities

Understanding liabilities

![]() Examining equity

Examining equity

Picture a tightrope walker carefully making her way across a tightrope. Now imagine that she's carrying plates of equal weight on both sides of a wobbling rod. What would happen if one of those plates were heavier than the other? You don't have to understand squat about physics to know that it isn't gonna be a pretty sight.

Just as a tightrope walker must be in balance, so must a company's financial position. If the assets aren't equal to the claims against those assets, then that company's financial position isn't in balance, and everything topples over. In this chapter, I introduce you to the balance sheet, which gives the financial report reader a snapshot of a company's financial position.

Understanding the Balance Equation

A company keeps track of its financial balance on a balance sheet, which is a summary of the company's financial standing at a particular point in time. To understand balance sheets, you first have to understand the following terms, which typically appear on a balance sheet:

- Assets: Anything the company owns, from cash, to inventory, to the paper it prints the reports on

- Liabilities: Debts the company owes

- Equity: Claims made by the company's owners, such as shares of stock

The assets a company owns are equal to the claims against that company, by either debtors (liability) or owners (equity). The claims side must equal the assets side for the balance sheet to stay in balance. The parts always balance according to this formula:

- Assets = Liabilities + Equities

Introducing the Balance Sheet

Trying to read a balance sheet without having a grasp of its parts is a little like trying to translate a language you've never spoken — you may recognize the letters, but the words don't mean much. Unlike a foreign language, however, a balance sheet is pretty easy to get a fix on as soon as you figure out a few basics.

Digging into dates

The first parts to notice when looking at the financial statements are the dates indicated at the top of the statements. You need to know what date or period of time the financial statements cover. This information is particularly critical when you start comparing results among companies. You don't want to compare the 2012 results of one firm with the 2011 results of another. Economic conditions certainly vary, and the comparison doesn't give you an accurate view of how well the companies competed in similar economic conditions.

On a balance sheet, the date at the top is written after “As of,” meaning that the balance sheet reports a company's financial status on that particular day. A balance sheet differs from other kinds of financial statements, such as the income statement or statement of cash flows, which show information for a period of time such as a year, a quarter, or a month. I discuss income statements in Chapter 7 and statements of cash flows in Chapter 8.

If a company's balance sheet states “As of December 31, 2012,” the company is most likely operating on the calendar year. Not all firms end their business year at the end of the calendar year, however. Many companies operate on a fiscal year instead, which means they pick a 12-month period that more accurately reflects their business cycles. For example, most retail companies end their fiscal year on January 31. The best time of year for major retail sales is during the holiday season and post-holiday season, so stores close the books after those periods end.

To show you how economic conditions can make comparing the balance sheets of two companies difficult during two different fiscal years, consider an example surrounding the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001.

If one company's fiscal year runs from September 1 to August 31 and another's runs from January 1 to December 31, the results may be very different. The company that reports from September 1, 2000, to August 31, 2001, wasn't impacted by that devastating event on its 2000/2001 financial reports. Its holiday season sales from October 2000 to December 2000 are likely much different from those of the company that reports from January 1, 2001, to December 31, 2001, because those results include sales after September 11, when the economy slowed considerably. However, the first company's balance sheet for September 1, 2001, to August 31, 2002, shows the full impact of the attacks on its financial position.

Nailing down the numbers

As you start reading the financial reports of large corporations, you see that they don't use large numbers to show billion-dollar results (1,000,000,000) or carry off an amount to the last possible cent, such as 1,123,456,789.99. Imagine how difficult reading such detailed financial statements would be!

At the top of a balance sheet or any other financial report, you see a statement indicating that the numbers are in millions, thousands, or however the company decides to round the numbers. For example, if a billion-dollar company indicates that numbers are in millions, you see 1 billion represented as 1,000 and 35 million as 35. The 1,123,456,789.99 figure would appear as 1,123.

Figuring out format

Balance sheets come in three different styles: the account format, the report format, and the financial position format. I show you a sample of each format in the following figures, using simple numbers to give you an idea of what you can expect to see. Of course, real balance sheets have much larger and more complex numbers.

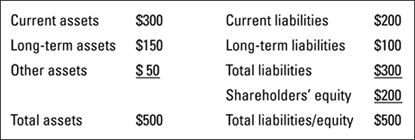

Account format

The account format is a horizontal presentation of the numbers, as Figure 6-1 shows.

Figure 6-1: The account format.

A balanced sheet shows total assets equal to total liabilities/equity.

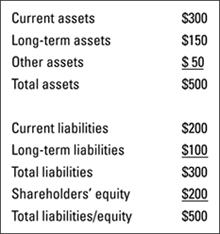

Report format

The report format is a vertical presentation of the numbers. You can check it out in Figure 6-2.

Figure 6-2: The report format.

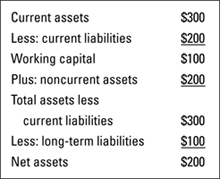

Financial position format

Companies in the U.S. rarely use the financial position format, although it is common internationally, especially in Europe. The key difference between this format and the other two is that it has two lines that don't appear on the account and report formats:

- Working capital: This line indicates the current assets the company has available to pay bills. You find the working capital by subtracting the current assets from the current liabilities.

- Net assets: This line shows what's left for the company's owners after all liabilities have been subtracted from total assets.

Figure 6-3 shows you what the financial position format looks like. (Keep in mind that noncurrent assets are long-term assets as well as assets that aren't current but also aren't long term, such as stock ownership in another company.)

Figure 6-3: The financial position format.

Ogling Assets

Anything a company owns is considered an asset. Assets can include something as basic as cash or as massive as a factory. A company must have assets to operate the business. The asset side of a balance sheet gives you a summary of what the company owns.

Current assets

Anything a company owns that it can convert to cash in less than a year is a current asset. Without these funds, the company wouldn't be able to pay its bills and would have to close its doors. Cash, of course, is an important component of this part of the balance sheet, but a company uses other assets during the year to pay the bills.

Cash

For companies, cash is basically the same as what you carry around in your pocket or keep in your checking and savings accounts. Keeping track of the money is a lot more complex for companies, however, because they usually keep it in many different locations. Every multimillion-dollar corporation has numerous locations, and every location needs cash.

Even in a centralized accounting system, in which all bills are paid in the same place and all money is collected and put in the bank at the same time, a company keeps cash in more than one location. Keeping most of the money in the bank and having a little cash on hand for incidental expenses doesn't work for most companies.

For example, retail outlets and banks need to keep cash in every cash register or under the control of every teller to be able to transact business with their customers. Yet a company must have a way of tracking its cash and knowing exactly how much it has at the end of every day (and sometimes several times a day, for high-volume businesses). The cash drawer must be counted out, and the person counting out the draw must show that the amount of cash matches up with the total that the day's transactions indicate should be there.

If a company has a number of locations, each location likely needs a bank to deposit receipts and get cash as needed. So a large corporation has a maze of bank accounts, cash registers, petty cash, and other places where cash is kept daily. At the end of every day, each company location calculates the cash total and reports it to the centralized accounting area.

Managing cash is one of the hardest jobs because cash can so easily disappear if proper internal controls aren't in place. Internal controls for monitoring cash are usually among the strictest in any company. If this subject interests you, you can find out more about it in any basic accounting book, such as Accounting For Dummies, 5th Edition, by John A. Tracy (published by Wiley).

Accounts receivable

Any company that allows its customers to buy on credit has an accounts receivable line on its balance sheet. Accounts receivable is a collection of individual customer accounts listing money that customers owe the company for products or services they've already received.

A company must carefully monitor not only whether a customer pays, but also how quickly she pays. If a customer makes her payments later and later, the company must determine whether to allow her to get additional credit or to block further purchases. Although the sales may look good, a nonpaying customer hurts a company because she's taking out — and failing to pay for — inventory that another customer could've bought. Too many nonpaying or late-paying customers can severely hurt a company's cash-flow position, which means the firm may not have the cash it needs to pay the bills.

Marketable securities

Marketable securities are a type of liquid asset, meaning they can easily be converted to cash. They include holdings such as stocks, bonds, and other securities that are bought and sold daily.

Securities that a company buys primarily as a place to hold on to assets until the company decides how to use the money for its operations or growth are considered trading securities. Marketable securities held as current assets fit in this category. A company must report these assets at their fair value based on the market value of the stock or bond on the day the company prepares its financial report.

A firm must report any unrealized losses or gains — changes in the value of a holding that it hasn't sold — on marketable securities on its balance sheet to show the impact of those losses or gains on the company's earnings. The amount you find on the balance sheet is the net marketable value, the book value of the securities adjusted for any gains or losses that haven't been realized.

Inventory

Any products a company holds ready for sale are considered inventory. The inventory on the balance sheet is valued at the cost to the company, not at the price the company hopes to sell the product for. Companies can pick from among five different methods to track inventory, and the method they choose can significantly impact the bottom line. Following are the different inventory tracking systems:

- First in, first out (FIFO): This system assumes that the oldest goods are sold first, and it's used when a company is concerned about spoilage or obsolescence. Food stores use FIFO because items that sit on the shelves too long spoil. Computer firms use it because their products quickly become outdated, and they need to sell the older products first. Assuming that older goods cost less than newer goods, FIFO makes the bottom line look better because the lowest cost is assigned to the goods sold, increasing the net profit from sales.

- Last in, first out (LIFO): This system assumes that the newest inventory is sold first. Companies with products that don't spoil or become obsolete can use this system. The bottom line can be significantly affected if the cost of goods to be sold is continually rising. The most expensive goods that come in last are assumed to be the first sold. LIFO increases the cost of goods figured, which, in turn, lowers the net income from sales and decreases a company's tax liability because its profits are lower after the higher costs are subtracted. Hardware stores that sell hammers, nails, screws, and other items that have been the same for years and won't spoil are good candidates for LIFO.

- Average costing: This system reflects the cost of inventory most accurately and gives a company a good view of its inventory's cost trends. As the company receives each new shipment of inventory, it calculates an average cost for each product by adding in the new inventory. If the firm frequently faces inventory prices that go up and down, average costing can help level out the peaks and valleys of inventory costs throughout the year. Because the price of gasoline rises and falls almost every day, gas stations usually use this type of system.

- Specific identification: This system tracks the actual cost of each individual piece of inventory. Companies that sell big-ticket items or items with differing accessories or upgrades (such as cars) commonly use this system. For example, each car that comes onto the lot has a different set of features, so the price of each car differs.

- Lower of cost or market (LCM): This system sets the value of inventory based on which is lower — the actual cost of the products on hand or the current market value. Companies that sell products with market values that fluctuate significantly use this system. For instance, a brokerage house that sells marketable securities may use this system.

Long-term assets

Assets that a company plans to hold for more than one year belong in the long-term assets section of the balance sheet. Long-term assets include land and buildings; capitalized leases; leasehold improvements; machinery and equipment; furniture and fixtures; tools, dies, and molds; intangible assets; and others. This section of the balance sheet shows you the assets that a company has to build its products and sell its goods.

Land and buildings

Companies list any buildings they own on the balance sheet's land and buildings line. Companies must depreciate (show that the asset is gradually being used up by deducting a portion of its value) the value of their buildings each year, but the land portion of ownership isn't depreciated.

Many people believe that depreciating the value of a building actually results in undervaluing a company's assets. The IRS allows 39 years for depreciation of a building; after that time, the building is considered valueless. That fact may be true in many cases, such as with factories that need to be updated to current-day production methods, but a well-maintained office building usually lasts longer. A company that has owned a building for 20 or more years may, in fact, show the value of that building depreciated below its market value.

Real estate over the past 20 years has appreciated (gone up in value) greatly in most areas of the country. So a building's value may actually increase because of market appreciation. You can't figure out this appreciation by looking at the financial reports, though. You have to find research reports written by analysts or the financial press to determine the true value of these assets.

Sometimes you see an indication that a company holds hidden assets — they're hidden from your view when you read the financial reports because you have no idea what the true marketable value of the buildings and land may be. For example, an office building that a company purchased for $390,000 and held for 20 years may have a marketable value of $1 million if it were sold today but has been depreciated to $190,000 over the past 20 years.

Capitalized leases

Whenever a company takes possession of or constructs a building by using a lease agreement that contains an option to purchase that property at some point in the future, you see a line item on the balance sheet called capitalized leases. It means that, at some point in the future, the company may likely own the property and then can add the property's value to its total assets owned. You can usually find a full explanation of the lease agreement in the notes to the financial statements.

Leasehold improvements

Companies track improvements to property they lease and don't own in the leasehold improvements account on the balance sheet. These items are depreciated because the improvements will likely lose value as they age.

Machinery and equipment

Companies track and summarize all machinery and equipment used in their facilities or by their employees in the machinery and equipment accounts on the balance sheet. These assets depreciate just like buildings, but for shorter periods of time, depending on the company's estimate of their useful life.

Furniture and fixtures

Some companies have a line item for furniture and fixtures, whereas others group these items in machinery and equipment or other assets. You're more likely to find furniture and fixture line items on the balance sheet of major retail chains that hold significant furniture and fixture assets in their retail outlets than on the balance sheet for manufacturing companies that don't have retail outlets.

Tools, dies, and molds

You find tools, dies, and molds on the balance sheet of manufacturing companies, but not on the balance sheet of businesses that don't manufacture their own products. Tools, dies, and molds that are unique and are developed specifically by or for a company can have significant value. This value is amortized, which is similar to the depreciation of other tangible assets. I discuss depreciation and amortization in Chapter 4.

Intangible assets

Any assets that aren't physical — such as patents, copyrights, trademarks, and goodwill — are considered intangible assets. Patents, copyrights, and trademarks are actually registered with the government, and a company holds exclusive rights to these items. If another company wants to use something that's patented, copyrighted, or trademarked, it must pay a fee to use that asset.

Patents give companies the right to dominate the market for a particular product. For example, pharmaceutical companies can be the sole source for a drug that's still under patent. Copyrights also give companies exclusive rights for sale. Copyrighted books can be printed only by the publisher or individual who owns that copyright, or by someone who has bought the rights from the copyright owner.

Goodwill is a different type of asset, reflecting the value of a company's locations, customer base, or consumer loyalty, for example. Firms essentially purchase goodwill when they buy another company for a price that's higher than the value of the company's tangible assets or market value. The premium that's paid for the company is kept in an account called Goodwill that's shown on the balance sheet.

Other assets

Other assets is a catchall line item for items that don't fit into one of the balance sheet's other asset categories. The items shown in this category vary by company; some firms group both tangible and intangible assets here.

Other companies may put unconsolidated subsidiaries or affiliates in this category. Whenever a company owns less than a controlling share of another company (less than 50 percent) but more than 20 percent, it must list the ownership as an unconsolidated subsidiary (a subsidiary that's partially but not fully owned) or an affiliate (a company that's associated with the corporation but not fully owned). I talk more about consolidation and affiliation in Chapter 10 .

Ownership of less than 20 percent of another company's stock is tracked as a marketable security (see the section “Marketable securities,” earlier in this chapter). Long before a firm reaches even the 20 percent mark, you usually find discussion of its buying habits in the financial press or in analysts’ reports. Talk of a possible merger or acquisition often begins when a company reaches the 20 percent mark.

You usually don't find more than a line item that totals all unconsolidated subsidiaries or affiliates. Sometimes the notes to the financial statements or the management's discussion and analysis sections mention more detail, but you often can't tell by reading the financial reports and looking at this category what other businesses the company owns. You have to read the financial press or analyst reports to find out the details.

Accumulated depreciation

On a balance sheet, you may see numerous line items that start with accumulated depreciation. These line items appear under the type of asset whose value is being depreciated or shown as a total at the bottom of long-term assets. Accumulated depreciation is the total amount depreciated against tangible assets over the life span of the assets shown on the balance sheet. I explain depreciation in greater detail in Chapter 4.

Although some companies show accumulated depreciation under each of the long-term assets, it's becoming common for companies to total accumulated depreciation at the bottom of the balance sheet's long-term assets section. This method of reporting makes it harder for you to determine the actual age of the assets because depreciation isn't indicated by each type of asset. You have no idea which assets have depreciated the most — in other words, which ones are the oldest.

Looking at Liabilities

Companies must spend money to conduct their day-to-day operations. Whenever a company makes a commitment to spend money on credit, be it short-term credit using a credit card or long-term credit using a mortgage, that commitment becomes a debt or liability.

Current liabilities

Current liabilities are any obligations that a company must pay during the next 12 months. These include short-term borrowings, the current portion of long-term debt, accounts payable, and accrued liabilities. If a company can't pay these bills, it may go into bankruptcy or out of business.

Short-term borrowings

Short-term borrowings are usually lines of credit a company takes to manage cash flow. A company borrowing this way isn't much different from you using a credit card or personal loan to pay bills until your next paycheck. As you know, these types of loans usually carry the highest interest-rate charges, so if a firm can't repay them quickly, it converts the debt to something longer term with lower interest rates.

Current portion of long-term debt

This line item of the balance sheet shows payments due on long-term debt during the current fiscal year. The long-term liabilities section reflects any portion of the debt that a company owes beyond the current 12 months.

Accounts payable

Companies list money they owe to others for products, services, supplies, and other short-term needs (invoices due in less than 12 months) in accounts payable. They record payments due to vendors, suppliers, contractors, and other companies they do business with.

Accrued liabilities

Liabilities that a company has accrued but hasn't yet paid at the time it prepares the balance sheet are totaled in accrued liabilities. For example, companies include income taxes, royalties, advertising, payroll, management incentives, and employee taxes they haven't yet paid in this line item. Sometimes a firm breaks out items individually, like income taxes payable, without using a catchall line item called accrued liabilities. When you look in the notes, you see more details about the types of financial obligations included and the total of each type of liability.

Long-term liabilities

Any money a business must pay out for more than 12 months in the future is considered a long-term liability. Long-term liabilities don't throw a company into bankruptcy, but if they become too large, the company may have trouble paying its bills in the future.

Many companies keep the long-term liabilities section short and sweet, and group almost everything under one lump sum, such as long-term debt. Long-term debt includes mortgages on buildings, loans on machinery or equipment, or bonds the company needs to repay at some point in the future. Other companies break out the type of debt, showing mortgages payable, loans payable, and bonds payable.

For example, both Hasbro and Mattel take the short-and-sweet route, giving the financial report reader little detail on the balance sheet. Instead, a reader must dig through the notes and management's discussion and analysis to find more details about the liabilities.

Navigating the Equity Maze

The final piece of the balancing equation is equity. All companies are owned by somebody, and the claims that owners have against the assets the company owns are called equity. In a small company, the equity owners are individuals or partners. In a corporation, the equity owners are shareholders.

Stock

Stock represents a portion of ownership in a company. Each share of stock has a certain value, based on the price placed on the stock when it's originally sold to investors. The current market value of the stock doesn't affect this price; any increase in the stock's value after its initial offering to the public isn't reflected here. The market gains or losses are actually taken by the shareholders, not the company, when the stock is bought and sold on the market.

Some companies issue two types of stock:

- Common stock: These shareholders own a portion of the company and have a vote on issues. If the board decides to pay dividends (a certain portion per share it pays to common shareholders from profits), common shareholders get their portion of those dividends as long as the preferred shareholders have been paid in full.

-

Preferred stock: These shareholders own stock that's actually somewhere in between common stock and a bond (a long-term liability to be paid back over a number of years). Although they don't get back the principal they pay for the stock, as a bondholder does, these shareholders have first dibs on any dividends.

Preferred shareholders are guaranteed a certain dividend each year. If a company doesn't pay dividends for some reason, it accrues these dividends for future years and pays them when it has enough money. A company must pay preferred shareholders their accrued dividends before it pays any money to common shareholders. The disadvantage for preferred shareholders is that they have no voting rights in the company.

You may also find Treasury stock in the equity section of the balance sheet. This is stock that the company has bought back from shareholders. Many companies did that between 2008 and 2013, so look for that on balance sheets. When a company buys back stock, it means less shares on the market. With fewer shares available for purchase on the open market, stock prices tend to rise.

If a firm goes bankrupt, the bondholders hold first claim on any money remaining after the company pays the employees and secured debtors (debtors who've loaned money based on specific assets, such as a mortgage on a building). The preferred shareholders are next in line; the common shareholders are at the bottom of the heap and are frequently left with valueless stock.

Retained earnings

Each year, companies make a choice to either pay out their net profit to their shareholders or retain all or some of the profit for reinvesting in the company. Any profit a company doesn't pay to shareholders over the years accumulates in an account called retained earnings.

Capital

You don't find this line item on a corporation's financial statement, but you'll likely find it on the balance sheet of a small company that isn't publicly owned. Capital is the money that the company's founders initially invested.

If you don't see this line item on the balance sheet of a small, privately owned company, the owners likely didn't invest their own capital to get started, or they already took out their initial capital when the company began to earn money.

Drawing

Drawing is another line item you don't see on a corporation's financial statement. Only unincorporated businesses have a drawing account. This line item tracks money that the owners take out from the yearly profits of a business. After a company is incorporated, owners can take money as salary or dividends, but not on a drawing account.

As a company and its assets grow, its liabilities and equities grow in similar proportion. For example, whenever a company buys a major asset, such as a building, it has to either use another asset to pay for the building or use a combination of assets and liabilities (such as bonds or a mortgage) or equity (owner's money or outstanding shares of stock).

As a company and its assets grow, its liabilities and equities grow in similar proportion. For example, whenever a company buys a major asset, such as a building, it has to either use another asset to pay for the building or use a combination of assets and liabilities (such as bonds or a mortgage) or equity (owner's money or outstanding shares of stock). As investing becomes more globalized, you may start comparing U.S. companies with foreign companies. Or perhaps you are considering buying stock directly in European or other foreign companies. You need to become more familiar with the financial position format if you want to read reports from foreign companies. I take a closer look at regulations for foreign company reporting in Chapter

As investing becomes more globalized, you may start comparing U.S. companies with foreign companies. Or perhaps you are considering buying stock directly in European or other foreign companies. You need to become more familiar with the financial position format if you want to read reports from foreign companies. I take a closer look at regulations for foreign company reporting in Chapter  This type of liability should be a relatively low number on the balance sheet, compared with other liabilities. A number that isn't low may be a sign of trouble, indicating that the company is having difficulty securing long-term debt or meeting its cash obligations.

This type of liability should be a relatively low number on the balance sheet, compared with other liabilities. A number that isn't low may be a sign of trouble, indicating that the company is having difficulty securing long-term debt or meeting its cash obligations.