CHAPTER 7

Europe Is Repeating Mistakes of the 1930s

The Failure of Economics in the 1930s and the Rise of National Socialism

When the pandemic-driven recession hit the Eurozone in early 2020, many elected leaders and their voters were horrified to find that they had no fiscal or monetary policy levers with which to fight the swiftest and deadliest economic collapse in living memory. That sense of helplessness had the potential to undermine the already precarious electoral support for the European Project, which first came to light with the Eurozone crisis that began in 2010.

Member states willingly ceded sovereignty over monetary and exchange rate policy to the European Central Bank (ECB) when they adopted the Euro. But they also lost sovereignty over fiscal policy—not only because of the limitations imposed by the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) and the subsequent Fiscal Compact, but also because of the ease with which capital can flow between the Eurozone's 19 different government bond markets—all of which use the same currency.

Under this arrangement, the unique position government bonds hold in each country as the highest-rated fixed income asset denominated in the national currency is lost since there are 18 other government bonds denominated in the same currency. Having 18 close substitutes means any member government deviating from the norm established by the best fiscal performer among the 19 countries is punished by capital outflows and higher interest rates.

This loss of fiscal sovereignty has been the key driver of poor performance of Eurozone economies since 2008 as well as the emergence of extreme-right anti-euro political parties in many member countries. And that was long before the onslaught of COVID-19. This alarming development manifested itself first in the 2010 Eurozone crisis, which left many voters with the impression that their elected officials had no monetary or fiscal policy levers to alter their economic future as long as they remained in the currency union. It is even more worrying that this political disillusionment is happening in economic circumstances very similar to those prevailing when similar far-right groups appeared in the 1930s.

It was already noted in Chapter 3 that Communism was a byproduct of the extreme inequality created in the course of industrialization before an economy reached the Lewis Turning Point (LTP). In contrast, the far-right National Socialism, or Nazism, was a result of extreme economic hardship brought about by an inept policy response to a balance sheet recession. In other words, it was policy makers' inability to understand that their economies were in Case 3 or 4 that led to that tragic outcome.

When the New York stock market bubble burst in October 1929, all of those who had leveraged up during the bubble started paying down debt at the same time. This can be seen in the sharp fall in loans outstanding after 1929 in Figure 2.15. But since there was no one on the other side to borrow and spend, the U.S. economy fell into the $1,000–$900–$810–$730 deflationary spiral and lost a full 46 percent of nominal gross national product (GNP) in just four years in an event that came to be known as the Great Depression. In 1933, the U.S. unemployment rate was more than 25 percent nationwide and exceeded 50 percent in many major cities.

The problem is that the economics profession never considered this type of recession until several years after 2008 because it never allowed for the possibility of a private sector that sought to minimize debt. The entire theoretical toolkit of economics, built over many decades, was predicated on the assumption that the private sector always seeks to maximize profits.

Because recessions driven by private-sector attempts to minimize debt had never been considered by economists, the public was totally unprepared for the balance sheet recessions that hit them in 1929 and again in 2008. Even Keynes, who argued for an increase in government spending in 1936, seven years after the Great Depression began, failed to free himself from the notion that the private sector is always maximizing profits.

With no-one in 1929 aware of the ailment called a balance sheet recession, it did not occur to political leaders of the time that the government should mobilize fiscal policy and act as borrower of last resort. On the contrary, most economists and policy makers, who never considered the possibility that the economy could be in Cases 3 or 4, argued strongly in favor of a balanced budget, believing that the private sector was still maximizing profits.

When the recession began in 1929, both U.S. President Herbert Hoover and German Chancellor Heinrich Brüning insisted that government should balance its budget as quickly as possible. The Allied Command, the victors of World War I, also demanded that the German government balance its budget and continue to make reparation payments. That was the worst possible policy for this type of recession because the economy would quickly fall into a deflationary spiral if the government abandoned its role as “borrower of last resort.” Soon enough, the German economy fell into a deflationary spiral that caused the unemployment rate to soar to 28 percent.

Although the Americans had only themselves to blame for getting caught up in a bubble, Germany was still recovering from the traumatic hyperinflation that followed its defeat in World War I and was very much dependent on U.S. capital when the New York stock market crashed. The extent of its reliance on American capital can be inferred from the saying in Germany in the 1920s that train passengers in the first-class cabin do not speak German at all, those in second class speak a little, and those in the ordinary cars speak it very well indeed. With American capital rushing back to the United States after the crash and the Allied powers demanding both a balanced budget and reparation payments, the German economy had no place to go but down.

The extreme hardship and poverty this mistaken policy imposed on the German people forced them to find a way out. With only a limited social safety net in the 1930s and the established center-right and center-left political parties largely beholden to orthodox economics and insisting on a balanced budget, the only choice left for the German people to alter their course after four years of terrible suffering was to vote for the National Socialists, who argued against both austerity and reparation payments.

The Nazis, considered by most Germans to be a gang of racist hoodlums just a few years earlier, thus ended up winning 43.9 percent of the vote and securing the chancellorship in 1933. It was not as if nearly half the German population woke up one morning and suddenly began hating immigrants and Jews. What happened was that they finally lost faith in established parties that remained beholden to fiscal orthodoxy. People voted for the Nazis because the established parties, the Allied governments, and the economists had proved totally incapable of rescuing them from the four years of horrendous poverty that followed the crash of 1929. The Nazis were swept to power because economists of that period failed to understand the horror of the balance sheet recession that had led to so much suffering for the German people.

For better or for worse, Adolf Hitler quickly implemented the speedy, sufficient, and sustained fiscal stimulus needed to overcome a balance sheet recession—the construction of the autobahn expressway system was among the many public works projects undertaken by the Nazi government. That started the positive feedback loop of fiscal stimulus that can be expected when the economy is in Case 3. By 1938, just five years later, Germany's unemployment rate had fallen to 2 percent.

This was viewed as a great success by people both inside and outside Germany—in contrast, the democracies of the United States, France, and the United Kingdom continued to suffer from high unemployment as policy makers were unable to think outside the box of orthodox economics insisting on balancing the budget. The U.S. unemployment rate, for example, was still 19 percent in 1938. The stark contrast between this and Germany's 2 percent rate made Hitler seem like an attractive alternative, and even those who used to look down their noses at the ranting lance corporal from Austria began to worship the man.

Germany's spectacular economic success also led Hitler to think that perhaps this time the nation could win a war—its economy, after all, was in a virtuous cycle and generating the taxes needed to support rearmament efforts, while the U.S., U.K., and French economies were in a vicious cycle of unattended balance sheet recessions with ever-dwindling tax receipts and military budgets.

That is what led to the cataclysm of World War II. Nothing is worse than a dictator who has the wrong agenda but the right economic policy. And the problem was made far worse in the 1930s by democracies' inability to switch to the right economic policy until hostilities began.

Once war broke out, the democracies were finally able to introduce the same sorts of policies Hitler had implemented six years earlier. In other words, Allied governments started acting as borrower and spender of last resort by procuring massive numbers of tanks and fighter planes, and the U.S. and U.K. economies jumped back to life, just as the German economy had done six years earlier.

This happened because companies that received large government orders to build fighter planes or warships were able to borrow from banks to expand their capacity. They could do so even if their balance sheets were not yet presentable because they already had the most credible buyer in the world for their products, the government. That started a virtuous cycle of over-stretching by businesses that led to rapid growth. The combined productive capacity of the Allies soon overwhelmed that of the Third Reich, but not before millions had perished.

Every country has its share of xenophobic persons who blame immigrants and foreigners for society's problems. But their ability to garner enough votes to emerge victorious in Germany despite the region's democratic traditions and high levels of education suggests that ordinary people who traditionally voted for parties espousing democratic values switched allegiance in desperation. It has been observed time and again that when survival is at stake, respect for individuals and human rights is often thrown out the window. And that is when things can go wrong in a big way.

The Nazis' initial successes and the tragedies that followed were attributable largely to a lack of understanding of balance sheet recessions among the period's economists and policy makers. Had Allied governments and the Brüning administration understood the mechanics and dangers of balance sheet recessions and administered sufficient fiscal stimulus to fight deflationary pressures in Germany, most Germans would never have voted for an extremist like Hitler.

If Allied governments had also administered sufficient fiscal stimulus after 1929 or even 1933 to prevent deflationary spirals in their own economies, Hitler's success would not have appeared so spectacular by contrast. And if stronger Allied economies had been able to present a credible military deterrent, Hitler might have thought twice about starting a war. The failure of economists to understand balance sheet recessions in the 1930s therefore contributed significantly to the Nazis' initial success and all the human suffering that followed.

History Is Repeating Itself since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2008

Fifty million lives were lost in World War II, and readers may think such a tragic mistake could never be repeated. Unfortunately, that is not the case, especially in Europe.

When housing bubbles burst on both sides of the Atlantic in 2008, the Western economies fell into a severe balance sheet recession, with private sectors increasing savings or paying down debt in spite of zero or negative interest rates.

Figure 7.1 illustrates the financial position of the household sector in Eurozone countries that experienced housing bubbles. It shows that households in these countries were either borrowing huge sums of money (i.e., were running a financial deficit) or reducing savings to invest in houses during the bubble, but after the bubble burst, they all began saving (i.e., were running a financial surplus)—some to a massive extent—in spite of zero interest rates. That puts these economies squarely in Cases 3 and 4.

The plight of the Spanish and Irish household sectors is noted in Chapter 2. Their nonfinancial corporate sectors have also been going through very difficult times since 2008. The Spanish nonfinancial corporate sector, shown in Figure 7.2, has been a significant net saver since 2008 despite low or even negative interest rates. It is particularly worth noting that the white bars for the nonfinancial corporate sector in Figure 7.2 frequently went below zero starting in 2008.

White bars below zero are a bad sign because they usually indicate that a credit crunch or a steep drop in income is forcing the sector to draw down past savings to make ends meet. That means Spain was suffering from both balance sheet problems (shaded bars above zero) and a credit crunch (white bars below zero). In other words, the Spanish economy was often in Case 4 if not in Case 3 from 2008 to 2016.

FIGURE 7.1 Eurozone Household Sectors1 Are Savers in Post-Bubble Era

Notes: 1. All entries are four-quarter moving averages. For the latest figures, four-quarter averages ending in 2021 Q3 are used.

Sources: Based on the flow of funds data from Banco de España; National Statistics Institute, Spain; the Central Bank of Ireland; Central Statistics Office Ireland; Banco de Portugal; Banca d'Italia; Italian National Institute of Statistics, and the International Monetary Fund (IMF)

The Spanish economy did better from 2016 until the pandemic recession hit in 2020, but the recovery was not fueled by domestic demand, as both the household and corporate sectors remained net savers. Instead, it was driven by a sharp contraction in the nation's external deficit as imports shrank faster than exports. And that was made possible by reduced domestic demand and the increased competitiveness of Spanish industry due to years of painful internal deflation. This latter possibility is discussed later in regard to the path of unit labor costs in Figure 7.9.

FIGURE 7.2 Spanish Nonfinancial Corporations

Notes: Seasonal adjustments by Nomura Research Institute. Latest figures are for 2021 Q3.

Sources: Nomura Research Institute, based on flow of funds data from Banco de España and National Statistics Institute, Spain

The Spanish corporate sector remained in financial surplus (i.e., was a net saver) for years after 2008 in spite of zero or negative interest rates. This aversion to borrowing may be a result of the painful credit crunch that struck Spain during the Eurozone crisis. Corporate treasurers who have lived through a credit crunch typically become extremely averse to borrowing, and such trauma can last for years.

The Irish nonfinancial corporate sector was also mostly a net saver (Figure 7.3) from 2008 until 2018. The fact that the Irish household sector was a huge net saver (Figure 2.7) suggests the Irish economic growth observed from 2016 to 2019 was also a result of lower wages due to internal deflation (see Figure 7.9), coupled with the country's tax haven status.

Greek households (Figure 7.4) were not as highly leveraged as their Spanish or Irish counterparts even though Greek house prices also soared (Figure 2.4). Nevertheless, the sector has been paying down debt since 2010, as indicated by the shaded bars above zero. This is a natural reaction for any sector caught in a bubble bust.

FIGURE 7.3 Irish Nonfinancial Corporations

Notes: Seasonal adjustments by Nomura Research Institute. Latest figures are for 2021 Q3.

Source: Nomura Research Institute, based on flow of funds data from the Central Bank of Ireland and Central Statistics Office, Ireland

What is really disturbing about the Greek household and nonfinancial corporate sectors is that they have been drawing down financial assets since the end of 2009, as indicated by the white bars below zero (circled areas in Figures 7.4 and 7.5). As noted earlier, white bars below zero are very bad signs, because they indicate that people are drawing down past savings to make ends meet. Such withdrawals are typically triggered by a credit crunch involving troubled financial institutions or by a significant fall in income. With Greek gross domestic product (GDP) down nearly 30 percent from 2008 (Figure 7.6), it is understandable that many Greek households and nonfinancial corporations are being forced to dis-save just to pay for daily necessities. That means the low savings figures for Greece in Figure 1.1 are due not to strong investment but rather to weak income.

One reason Greece's GDP fell so sharply was that the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which was called in to help the country following the deficit-fudging scandal in 2010, had no understanding of balance sheet recessions at the time (it does now). The IMF forced the country to engage in draconian fiscal consolidation in the hope that this would win back creditors' trust. Although that would be the right course of action for a country in an ordinary fiscal crisis, Greece was also in a balance sheet recession, and the austerity measures triggered the $1,000–$900–$810–$730 deflationary spiral, causing nominal GDP to contract by nearly 30 percent (Figure 7.6).

FIGURE 7.4 Greek Households Deleveraging but also Drawing Down Savings to Survive

Notes: Seasonal adjustments by Nomura Research Institute. Latest figures are for 2021 Q3.

Sources: Nomura Research Institute, based on flow of funds data from the Bank of Greece and Hellenic Statistical Authority, Greece

The Greek government lost the market's trust when it was revealed that its pre-2009 government had been fudging the budget deficit numbers and the actual deficit was much larger than reported. However, the IMF and the EU also lost their credibility in the eyes of the Greek people when the economic package they imposed not only failed to meet its own growth projections, but also ended up depressing the nation's GDP by nearly 30 percent. Now that both sides have made one massive mistake each, it is time for them to call it even and move forward.

FIGURE 7.5 Greek Nonfinancial Corporate Sector also Drew Down Savings during Crisis

Notes: Seasonal adjustments by Nomura Research Institute. Latest figures are for 2021 Q3.

Sources: Nomura Research Institute, based on flow of funds data from the Bank of Greece and Hellenic Statistical Authority, Greece

FIGURE 7.6 Greece's Nominal GDP Falls Far below IMF Forecasts

Source: Nomura Research Institute, based on Hellenic Statistical Authority, Greece; IMF, “IMF Executive Board Approves €30 Billion Stand-By Arrangement for Greece” May 9, 2010

Germany's Balance Sheet Recession Preceded Others by Eight Years

In contrast to the peripheral countries previously noted, Germany, the largest of the Eurozone countries, experienced no housing bubble (Figure 2.4). Not only that, but German house prices actually fell 8 percent while house prices in other parts of the Eurozone rose sharply, all under the same low interest rates.

This happened because Germany had entered a balance sheet recession eight years earlier, in 2000, when the dot-com bubble burst. This can be seen from Figure 7.7, which shows that German households not only stopped borrowing money after 2000, but also started paying down debt. And that was happening even after the ECB took interest rates down to their lowest level in the postwar period.

This change in household behavior happened because German households and businesses, who are usually very conservative, apparently lost their heads during the dot-com bubble in the Neuer Markt, the German equivalent of the Nasdaq, which went up tenfold from 1998 to 2000 (Figure 7.8).1 When the bubble burst and the market lost 97 percent of its value, the financial health of Germany's private sector was devastated. Businesses and households went on to save as much as 10 percent of GDP in the wake of bubble burst, tipping the economy into a severe balance sheet recession.

Seeing that the German economy was in trouble, but not realizing that it was in a balance sheet recession, the ECB promptly brought interest rates down to a postwar low of 2 percent to help the largest economy in the Eurozone, but to no avail. This inability to revive Germany's economy with record-low interest rates led to the notion that the country was “the sick man of Europe.”

The Germans, without realizing that their problems were rooted in the balance sheet, began to push for structural reforms in a plan known as Agenda 2010. Because balance sheet recessions were not taught in economics, German economists and policy makers simply assumed that traditional monetary easing was not working because of structural problems. It was the same mistake Japan had made a decade earlier, and for exactly the same reason.

FIGURE 7.7 German Households Stopped Borrowing Altogether after Dot-Com Bubble

Notes: Seasonal adjustments by Nomura Research Institute. Latest figures are for 2021 Q3.

Sources: Nomura Research Institute, based on flow of funds data from Bundesbank and Eurostat

FIGURE 7.8 Neuer Markt Collapse in 2001 Pushed German Economy into Balance Sheet Recession

Sources: Bloomberg and MarketWatch, as of March 14, 2022

However, structural issues that existed decades before 2000 cannot explain the sudden shift in German private-sector savings behavior starting in that year (Figure 7.7). This fundamental misdiagnosis created huge distortions in the Eurozone economies after 2000 and again after 2008, when Germany began demanding that other economies in the currency bloc implement the same structural reforms it had carried out even though those economies were all suffering from balance sheet—not structural—problems.

While Germany was struggling with both a balance sheet recession and painful structural reforms that were no cure for the recession, Eurozone countries that had avoided the dot-com bubble and had clean balance sheets responded enthusiastically to the ECB's monetary easing. In other words, the postwar-low interest rate of 2 percent designed to help the German economy was of no help to that country because its economy was in Case 3 with no private sector borrowers, but the same rate was far too low for the rest of Europe, which was in Case 1 with plenty of private sector borrowers. In no time, many of these countries found themselves engulfed in huge housing bubbles.

The fact that Germany was in a balance sheet recession while the other countries were experiencing housing bubbles also opened up a large competitive gap between the two. Slow money-supply growth in Germany, which was suffering from a balance sheet recession, led to stagnant wages and prices, while rapid money-supply growth in the rest of the bubble-ridden Eurozone resulted in sharply rising wages and prices. That made Germany highly competitive relative to the rest of Europe.2

The housing boom in the rest of Europe and improved competitiveness at home allowed the Germans to rapidly increase their exports within the region. With the rest of Europe doing the over-stretching for Germany, the country was able to overcome its balance sheet recession.

When the global housing bubble burst in 2008 and the rest of Europe plunged into a balance sheet recession, Germany was already emerging from its own balance sheet recession. This lack of synchronization between the German economy, the largest in the Eurozone, and the rest of the bloc, combined with policy makers' lack of awareness of the economic disease called a balance sheet recession, created prolonged difficulties for the Eurozone that lasted over 10 years.

If the private sector as a whole is saving, someone outside the private sector must borrow and spend those savings to prevent the economy from falling into a deflationary spiral. Unfortunately, in spite of dramatic increases in private-sector savings after 2008, the concept of balance sheet recessions was still not in economic textbooks, and powerful figures on both sides of the Atlantic started pushing for fiscal consolidation in a repeat of the 1930s.

In the United States, this move was spearheaded by the Tea Party faction of the Republican Party, and in the Eurozone, it was the Germans, led by Chancellor Angela Merkel and Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble, who pushed for austerity. In the United Kingdom, Prime Minister Gordon Brown was cognizant of balance sheet recessions and administered the required fiscal stimulus, but he was soon voted out of office in favor of David Cameron, who opted for draconian austerity measures.

Fortunately for the United States, policy makers from Ben Bernanke to Larry Summers recognized soon after the GFC that they were facing a balance sheet recession, the same economic ailment that had afflicted Japan since 1990. They then employed the expression “fiscal cliff” to persuade Congress not to engage in premature fiscal consolidation. Although the United States came close to falling off the fiscal cliff on several occasions, it ultimately managed to avoid that predicament and recovered faster than other countries, even though it had been the epicenter of the GFC.

Defective SGP Invites Extreme-Right Political Parties

In the Eurozone, where policy makers remained unaware of the ailment called a balance sheet recession or the need for government to act as borrower of last resort in such situations, one country after another fell off the fiscal cliff, with devastating consequences. The SGP that created the euro also made no provision whatsoever for this type of recession and actually prohibited governments from borrowing more than 3 percent of GDP regardless of how much the private sector was saving. In other words, Eurozone governments were prevented from acting as borrower of last resort beyond 3 percent of GDP.

The Spanish private sector saved an average of 7.64 percent of GDP in the 13 years after 2008 Q3 (Figure 1.1). But since the government was allowed to borrow only 3 percent of GDP, savings equal to more than 4 percent of GDP leaked out of the nation's income stream, tipping the Spanish economy into a horrendous recession.

Moreover, weakened economies saw tax receipts fall and budget deficits rise to more than 3 percent of GDP. An increase in the budget deficit due to economic weakness is referred to in economics as an automatic stabilizer because it forces government to increase borrowing and spending, which helps stabilize the economy.

But instead of utilizing this stabilizer function by expanding government borrowing to match the increase in private-sector savings, Eurozone governments were forced by the SGP to reduce their borrowing to 3 percent of GDP. Instead of mitigating the recession, these government actions made it far worse. The Spanish unemployment rate shot up to 26 percent, and many other countries suffered a similar fate. With center-left and center-right political parties alike insisting on the fiscal consolidation mandated by the SGP and the Fiscal Compact—not unlike German center-left and center-right political parties in the early 1930s—average citizens grew increasingly destitute and desperate.

Shockingly, the SGP offers no advice on how a government should address this kind of deflationary gap because it assumes that situations like Cases 3 and 4 can never happen. This is not surprising given that the SGP was ratified in 1998, when no one outside Japan knew anything about balance sheet recessions. But when the housing bubbles burst in 2008, triggering Europe's balance sheet recessions, policy makers were left with no tools to stop the deflationary spiral, resulting in deep recessions and tremendous human suffering not unlike what Germany experienced during the 1929–33 period. It is this fundamental defect in the SGP that nearly destroyed the Eurozone economies starting in 2008.

Predictions of Eurozone Crisis Are Ignored

This disastrous outcome was perfectly predictable given the SGP's limitations. The author tried to warn Europeans in his 2003 book, Balance Sheet Recession: “Since fiscal stimulus is the most effective—if not the only—remedy for a balance sheet recession, as soon as the symptoms of balance sheet recessions are observed in Europe, the EC Commission is strongly advised to take action to free the Eurozone economies from the restrictions of the Maastricht Treaty.3 Failure to do so may result in Europe falling into a vicious cycle with an ever-larger deflationary gap. Indeed, of the three regions—Japan, the United States, and Europe—Europe is by far the most vulnerable when it comes to balance sheet recessions because of the restrictions placed on it by the Maastricht Treaty.”4 Although the importance of the book was noted by Joseph Ackermann, the CEO of Deutsche Bank at the time, and was featured in the bank's report to its clients, the warning went unheeded, and one Eurozone economy after another fell into a prolonged balance sheet recession after 2008, exactly as predicted.

The author then warned about the political consequences of this problem in his 2008 book The Holy Grail of Macroeconomics, arguing that “… forcing a country or region in a balance sheet recession to balance the budget out of misguided pride or stubbornness will not benefit anyone. Indeed, forcing an inappropriate policy on a nation already suffering from a debilitating recession can actually put its democratic structures at risk by aggravating the downturn.”5 This warning, too, was ignored, and extremist parties have gained ground in all of these countries, just as predicted.

By May 2014, people had become so desperate that nationalist anti-EU parties shocked the political establishment with victories in European Parliament elections in the United Kingdom, France, and Greece. The United Kingdom also voted itself out of the EU in 2016, with some arguing that “the only continent that had lower growth rates than Europe was Antarctica!” These results underscore just how many people are unhappy and distrustful of the European political and economic establishment because of this critical defect in the SGP.

The gains made by Eurosceptics prompted both the establishment and the media to warn about a loss of momentum in the fiscal consolidation and structural reform efforts they consider essential to the region's economic revival. The powers-that-be have labeled the triumphant Eurosceptics “populists” and are desperately trying to paint them as irresponsible extremists.

All of the anti-EU parties that performed well in elections have elements of nativism in the sense that they blame immigrants for many of their countries' domestic problems. They are also irresponsible in that there is no reason why stricter controls on immigration would meaningfully improve the lives of people suffering from devastating balance sheet recessions.

Policy Makers Need to Ask Why Eurosceptics Made Such Gains

On the other hand, the establishment's claim that it has pursued responsible policies deserves to be critically reexamined. Most countries in Europe fell into severe balance sheet recessions after the housing bubble collapsed, yet not a single government has recognized that and responded appropriately. To make matters worse, establishment policies have centered on fiscal consolidation, which is the one policy a government must not implement during a balance sheet recession. That mistake has had devastating consequences for the people of Europe.

Moreover, the establishment has made the situation worse by mistaking balance sheet problems for structural problems. While every Eurozone country, as a pursued economy, needs to address a variety of structural problems to stay ahead of its pursuers, the recessions that started in 2008 were due mostly—perhaps about 80 percent—to balance sheet problems, with structural issues responsible only for the remaining 20 percent or so. After all, it is difficult to attribute the sudden collapse of these economies in 2008 and their subsequent stagnation to structural factors that had existed for decades prior to that. Furthermore, these economies were all responding normally to conventional macroeconomic policies until 2008 (2000 in Germany), indicating that there were no structural problems then.

As is noted in Chapter 5, all advanced countries are facing two challenges: they are being pursued and they are in balance sheet recessions—and, more recently, pandemic recessions. Structural reforms are necessary to address the former, but fiscal stimulus is needed to deal with the latter. Of the two, the latter is far more urgent because a balance sheet recession can destroy an economy very quickly, as demonstrated by the United States during the Great Depression in the 1930s. In a sense, the present situation is more serious than that of the 1930s because policy makers then only had to deal with a balance sheet recession.

As is noted in Chapter 5, structural reforms often take a decade or more to produce macroeconomic results and are no substitute for fiscal stimulus when the economy is in a balance sheet recession. Political leaders, therefore, must make it clear to voters that structural policies are needed to stay ahead of the pursuing countries, but if the economy is in a balance sheet recession, fiscal stimulus is urgently needed to offset the deflationary pressures coming from private-sector deleveraging. And that should not be too difficult to explain with charts like those in Figures 2.6 and 2.7.

The situation also varies from one country to the next. In Spain and Ireland, which experienced particularly large bubbles, balance sheet problems are responsible for a greater percentage of the ongoing economic weakness, while in Italy, which did not see a major bubble, the issues are probably more structural in nature.

Regardless of national differences, the Eurozone as a whole is in Case 3, with its private sector saving 5.11 percent of GDP on average since 2008 (Figure 1.1) in spite of negative interest rates. Since the economy is suffering from a lack of borrowers, governments must do the opposite of what the private sector is doing—they must support the economy by borrowing and spending the 5.11 percent of GDP worth of excess private-sector savings.

No Official Recognition of the Disease

Unfortunately, neither the European Commission (EC) nor the ECB seems cognizant of the danger posed by this alarming surplus of private-sector savings. As a result, they continue to demand fiscal consolidation and structural reforms from member countries while ignoring the most urgent need, which is to re-inject excess private-sector savings into the economy's income stream. For example, former ECB President Mario Draghi demanded at the beginning of each and every one of his press conferences that all Eurozone members observe the fiscal consolidation goals mandated by the SGP and the subsequent Fiscal Compact. That means he believed the Eurozone economy was in Case 2, where lenders and not borrowers are the constraint on growth.

His belief that the economy is in Case 2 led the ECB to introduce long-term refinancing operations (LTROs), targeted LTROs (TLTROs), quantitative easing (QE), and a negative-interest-rate policy—all of which are designed to increase lending, on the assumption that there is an ample supply of willing borrowers. Although some of these ECB policies did help the Eurozone economy move from Case 4 to Case 3 (but not completely, as is explained in Chapter 8), the actual credit extended to euro-area residents over the last 13 years increased by a minuscule 16 percent, as shown in Figure 2.13.

Since those who created the euro never anticipated Cases 3 and 4, fiscal policy was effectively banned in the Eurozone, leaving monetary policy as policy makers' only tool for addressing recessions. It was what Draghi called “the only game in town.” As a result, when Germany first fell into a balance sheet recession in 2000, the ECB had to ease monetary policy by lowering interest rates to a postwar low of 2 percent—thereby creating bubbles elsewhere in the Eurozone—to help the country. When the bubbles burst and those countries fell into balance sheet recessions in 2008, the ECB had to ease even further by taking interest rates below zero in a feeble attempt to help the rest. But fighting balance sheet recessions in one part of the Eurozone by creating bubbles elsewhere is no way to run a currency union.

The SGP Should Have Forced Countries in Case 3 to Use Fiscal Stimulus

Put differently, if Germany had used fiscal stimulus to fight its post-2000 balance sheet recession, the housing bubbles and subsequent balance sheet recessions the Eurozone suffered would not have been nearly as bad as they were. This is because the ECB would not have felt the need to bring interest rates to a postwar low to prop up the German economy, and higher interest rates would have meant smaller housing bubbles in the rest of Eurozone.

This suggests that, in order to make the single currency work, the SGP should have required member governments to combat balance sheet recessions within their borders using domestic fiscal policy. This would have insulated ECB's monetary policy and the other member economies from the influence of bubbles and balance sheet recessions in individual countries.

Restricting the use of fiscal policy when an economy is in Case 1 and 2 is fine. But when a country is in Case 3, the SGP should require it to mobilize fiscal policy with EU support and blessing so that its balance sheet problems do not distort the economic policies of countries that did not participate in the bubble.

The Eurosceptics have made gains not because they are populists, but because the established center-left and center-right parties' mistaken policy choices dragged the economy down and devastated so many lives. After waiting fruitlessly for many years, voters realized the situation was not going to improve as long as the established parties remained in power. For people whose lives had been destroyed by their governments' inaction (or worse) on the deflationary gap, the first step toward a solution was to free their countries from the fiscal straitjacket imposed by the defective SGP—hence the surge in support for anti-EU parties. And those are exactly the circumstances under which Adolf Hitler and the National Socialists came to power in Germany in 1933.

Germans, Who Suffered Most after 1929, Have Ironically Made Others Suffer since 2008

It is truly ironic that it is the Germans who are imposing this fiscal straitjacket on the Eurozone even though they were the first victims of a similar fiscal orthodoxy in 1929 when Allied governments imposed austerity measures on the Brüning administration. Those demands devastated the German economy and pushed its unemployment rate up to 28 percent, as noted earlier. If anything, it is the Germans who should be warning about the dangers of austerity when an economy is in Case 3. The Germans also appear to have forgotten how quickly their own economy recovered with fiscal stimulus after 1933.

Perhaps Germans today are so appalled by the brutality of the Nazi regime that everything Hitler did is now rejected out of hand. This kind of total repudiation of a person or an era can be dangerous because people who were never taught what he did right to win the hearts of the German people will be naïve and unprepared when the next Hitler comes.

With so many far-right political parties winning votes in countries suffering from balance sheet recessions, the people of Europe must urgently be made aware of this economic ailment. Without a proper understanding of the disease, member countries may find their economic crises accompanied by a crisis in democracy.

Social safety nets today are far more extensive than they were in the 1930s, making modern democracies more resistant to such recessions and policy mistakes. Indeed, social safety nets themselves are a form of fiscal stimulus that did not exist in the 1930s. Nevertheless, people's mistrust and unhappiness could eventually explode if complacent politicians, economists, and bureaucrats continue to implement misguided policies.

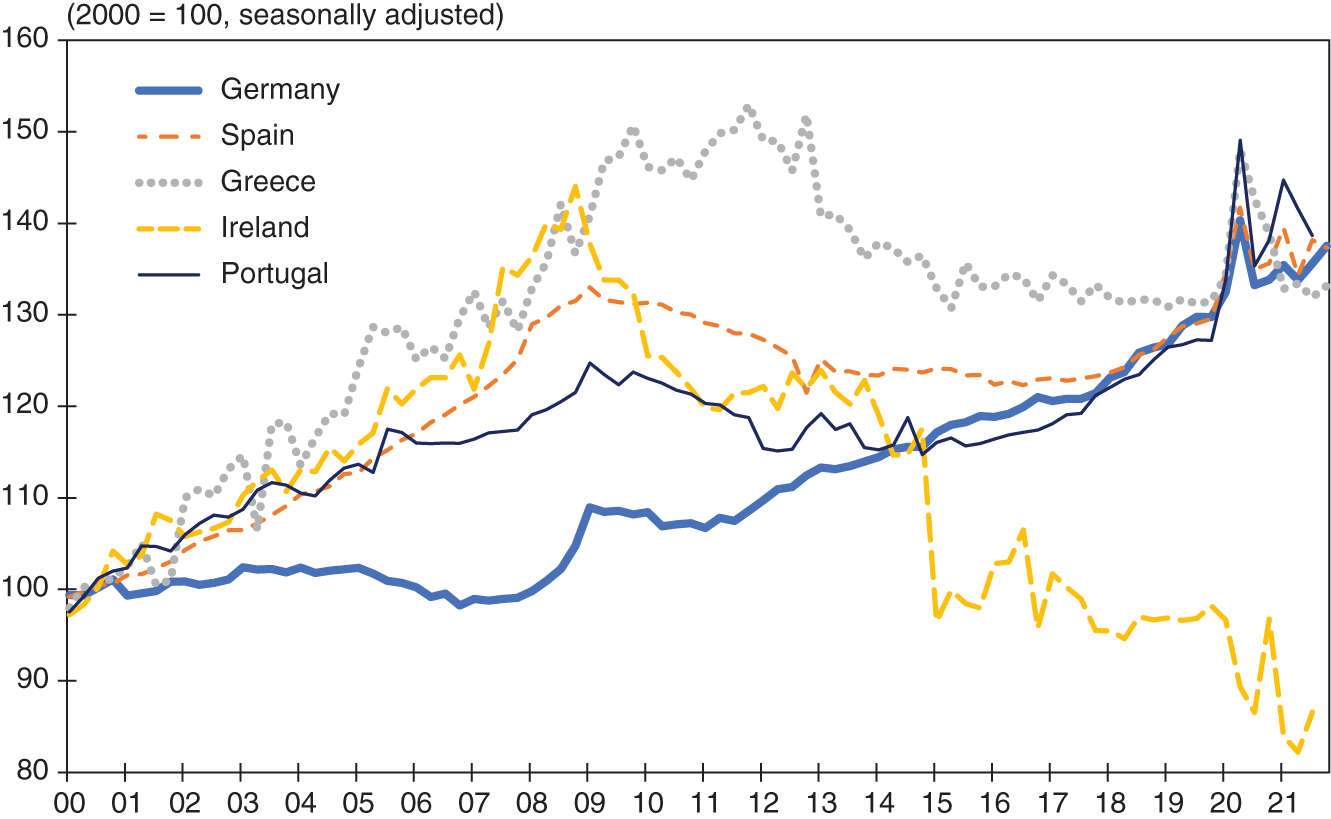

European Recovery Is Led by Internal Deflation

Economies do adjust given sufficient time. In spite of the misguided policies previously described, some European economies began to show signs of life from around 2016 until the onslaught of the pandemic. But that was a result of a painful internal deflation that made them more competitive relative to the outside world. Figure 7.9 shows that unit labor costs in high-unemployment countries like Spain, Ireland, Portugal, and Greece have all fallen quite substantially from their peaks. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), unit labor costs fell 14.5 percent from their previous peak in Greece, 8.6 percent in Spain, and 8.0 percent in Portugal. In Ireland, they plunged 42.9 percent from the high, although this decline may have been exaggerated by discontinuities in the Irish GDP data.

In contrast, German unit labor costs rose 42.8 percent from their low in 2006 Q4 as the country recovered from its post-2000 balance sheet recession. This divergence in unit labor costs made peripheral countries quite competitive vis-à-vis Germany and the rest of the world. The fact that post-2016 Spanish growth came from imports falling faster than exports indicates that it was indeed an internal deflation story. Although the ECB often talks about the importance of achieving the 2-percent inflation target, it was actually this painful internal deflation that allowed Eurozone's hardest-hit countries to recover in the absence of fiscal stimulus.

FIGURE 7.9 Euro Crisis Depressed Unit Labor Costs in Peripheral Countries

Source: Nomura Research Institute, based on OECD data

COVID-19 Exposes Defects in Eurozone Structures Again

It was against this backdrop that the COVID-19 pandemic struck Europe in 2020. When the economy was hit by the lockdowns, Eurozone voters realized once again that they had no monetary or fiscal policy levers to fight the devastating recession and public health crisis. This was in stark contrast to non-Eurozone governments, which could combat the pandemic and the recession it triggered by borrowing—especially from investors who must hold high-quality fixed income assets denominated in the domestic currency. In the United Kingdom, the Bank of England even offered to lend directly to the government on an emergency basis. These countries also have the option of allowing their exchange rates to weaken.

Support for the European project began to dissolve as more voters began to realize that their helplessness stemmed from their membership in the Eurozone. Support for the euro in Italy, which had held up during the Eurozone crisis, fell dramatically when the pandemic struck.

Fortunately, the EU seems to have learned from its mistakes during the Eurozone crisis and opted to suspend the Fiscal Compact limits on fiscal deficits during the pandemic, something the author had strongly recommended in his 2003 book. Furthermore, Angela Merkel and Emmanuel Macron recognized that the lack of fiscal response to the pandemic represented an existential threat to the European project. The two leaders then led the negotiations on a €750 billion euro-wide fiscal package to help the helpless. The two leaders recognized that if Eurozone voters felt their elected representatives were powerless to address the pandemic as long as they remained in the Eurozone, support for the euro and for democracy itself might crumble.

The two leaders overrode opposition from the Netherlands and a few other countries and weathered four days of tough negotiations to broker a package under which the EU would borrow €750 billion under its own name to help member countries hit hard by the pandemic. This one-off package was at least able to mitigate the suspicions held by many that they were doomed as long as they stayed in the Eurozone.

Whether this euro-wide fiscal package eventually leads to fiscal union remains an open question. If that were to happen, and the region's government bond markets were unified into a single market, the problem of capital flight between government bond markets mentioned at the beginning of the Chapter would disappear. That would allow the Eurozone, at least collectively, to wield fiscal policy like any other country. However, the fact that the arduous negotiations took four days and produced only €390 billion in grants—the actual “rescue” portion of the package—suggests a true consensus has yet to form on the question of fiscal union.

Even if they believe fiscal union is still far off, Eurozone leaders probably concluded that if the euro project is to be preserved, voters must never be left feeling helpless again. To ensure that voters feel empowered to decide their own future, the euro's institutional framework needs to be modified. Such discussions have already started.

The Euro's Institutional Defect

As noted at the beginning of this chapter, Europeans who voted to join the common currency more than two decades ago believed they were only giving up sovereignty over monetary policy. But as subsequent events have shown, they have effectively lost sovereignty over fiscal policy as well. That left national governments unable to respond to voter demands, placing their economies and democratic institutions at risk. This unintended consequence of the euro has both institutional and market-driven causes that must be addressed.

The institutional cause is that the SGP, which caps the fiscal deficits of member countries at 3 percent of GDP, never considered that an economy could be in Cases 3 or 4. In other words, it never envisioned a world in which the private sector was saving more than 3 percent of GDP at a time of zero interest rates. Proponents of the SGP, along with most of the economics profession, assumed the private sector would be borrowing, not saving, at such low interest rates.

But when the housing bubble burst on both sides of the Atlantic in 2008, the private sectors of all affected countries—both inside and outside the Eurozone—rushed to deleverage, saving far more than 3 percent of GDP after central banks had lowered interest rates to zero or even negative levels. Spain's private sector, for example, has been saving over 7 percent of GDP on average since 2008. And if someone is saving 7 percent of GDP, someone else must borrow and spend that 7 percent to keep the national economy from contracting. However, the SPG allowed the Spanish government to borrow only 3 percent of GDP, opening up a deflationary gap equal to 4 percent of GDP and plunging the country into a horrendous recession and internal deflation.

An obvious way to rectify this institutional defect would be to allow member governments to borrow more than 3 percent of GDP when the private sector is saving more than 3 percent of GDP at zero interest rates. This is a necessary condition—but not a sufficient condition—for rectifying the problems unique to the Eurozone.

Capital Flight Is at the Core of Eurozone Problems

This is because even if the SGP is revised in this way, member governments will still face an unforgiving market-driven constraint that has drastically undermined their fiscal policy sovereignty. As noted in the beginning of this chapter, this constraint stems from the fact that all government bonds issued by member governments are denominated in the same currency.

As is explained in Chapter 4, if the private sector in a non-euro country is a huge net saver—that is, if it is running a large financial surplus—in spite of zero interest rates, pension funds and other institutional investors who are entrusted with those savings but are unable to take on substantial foreign exchange risk or put all their money into equities will rush to purchase government bonds. The government, after all, is the only borrower left who is issuing highly rated fixed income assets denominated in the home currency.

This rush brings government bonds yields down to levels that would have been unthinkable when the economy was in Cases 1 and 2. If the government then carefully selects infrastructure projects capable of earning a social rate of return higher than the super-low yield on government bonds, the projects themselves will be self-financing. That allows the government to utilize the nation's savings to fight recessions without burdening future taxpayers. This is the self-corrective mechanism of economies in Cases 3 and 4 that is first noted in Chapter 2.

Eurozone investors, in contrast, can choose from 19 different government bond markets because they are all denominated in the same currency. That means there is no assurance that Spanish savings will be invested in Spanish government bonds or that Portuguese savings will be used to buy Portuguese government bonds.

During the Eurozone crisis that started in 2010, a huge amount of private-sector savings from the peripheral countries went into German government bonds, pushing yields on Bunds to unthinkably low levels while raising the yields on peripheral governments' bonds (Figure 7.10). That happened because the German economy was coming out of a (balance sheet) recession with a shrinking budget deficit, while other member countries were entering a (balance sheet) recession with expanding budget deficits. The foreign exchange risk that ring-fenced government bond markets and channeled excess domestic savings to their own government bond markets in non-Eurozone countries during balance sheet recessions could not do the same in the Eurozone. In other words, the self-corrective mechanism of economies in Cases 3 and 4 does not function very well in the Eurozone.

FIGURE 7.10 Eurozone-Specific Capital Flight Led to Eurozone Crisis

Source: Nomura Research Institute, based on data from ECB and Federal Reserve Board (FRB)

That also means the 19 government bond markets end up competing with each other, since investors can dump the debt of any member country that is running large fiscal deficits in favor of bonds issued by other governments that are fiscally better behaved. This often led to the perverse outcome of healthy economies in no need of money being flooded with funds, while countries in balance sheet recessions and desperately in need of funds for fiscal stimulus to counter recessions were unable to borrow, even when their own private sectors are generating plenty of savings.

Market-Based Fiscal Discipline Created a Backlash against Euro

Under this framework, the only options for the Eurozone were (1) to have Germany, the region's fiscal poster child, run much larger budget deficits and thereby enable the other 18 members to do the same, or (2) to have the less fiscally fortunate nations trim their deficits and draw closer to Germany. Germany rejected the first alternative, forcing the other countries with excess savings problems into option (2) with devastating consequences.

This was amply demonstrated during the 2010 Eurozone crisis, when investors sold off the government bonds of many peripheral countries even though every country except Greece was generating more than enough private-sector savings at home to finance its budget deficit. In other words, if those countries had been outside the Eurozone, they could have weathered the recession in the same way that the United States or Japan did. However, the sell-off in their government bond markets has prevented Eurozone governments from tapping their own national savings to fund necessary fiscal stimulus.

During the crisis, some unscrupulous U.S.- and U.K.-based investment funds made the situation worse by shorting peripheral government bonds while flooding the media with talk of so-called redenomination risk, that is, the imminent disintegration of the European Monetary Union (EMU). This attack on the euro was contained only when ECB President Draghi declared he would do “whatever it takes” to defend the EMU. Another sell-off was also observed in the Italian government bond market in 2018, when a newly elected government wanted to increase its fiscal spending by about 0.4 percent of GDP. The point is that the threat of such capital flight means no member country can utilize fiscal policy to a greater extent than the Eurozone's best fiscal performer, which at present happens to be Germany.

This loss of fiscal freedom due to “market pressure” persisted even after the constraints of the SGP and the Fiscal Compact were removed in spring of 2020. As the coronavirus spread rapidly throughout the region, the EU declared that the constraints of the Fiscal Compact could be ignored until June 2021. Member countries, however, were still unwilling to take major fiscal action because of concerns about a potential sell-off of their government bonds.

This Eurozone-specific, market-imposed fiscal straitjacket has robbed member countries of their fiscal sovereignty. And if member countries cannot utilize the savings generated by their own private sectors to fight economic downturns, voters will feel they are not in control of their economic destiny and will lose confidence in democratic structures and the euro.

Fiscal Dis-Union Is Needed to Make Monetary Union Work

One way to address this issue is to replace the current limit on fiscal deficits with a rule allowing only citizens of a country to hold bonds issued by the government, so that, for example, Portuguese government bonds could be held only by Portuguese citizens. While such a rule might sound outrageous at first, it would not only eliminate the capital flight problem previously described and restore full fiscal sovereignty to member governments, but would also help normalize ECB's monetary policy.

Allowing only the citizens of a country to hold its government's bonds solves the Eurozone-specific problem of capital flight among government bond markets. Institutional investors who need to buy the highest-rated fixed income assets will purchase their own government's bonds, thereby allowing governments to use the savings of their own private sectors to combat balance sheet recessions.

Under this fiscal dis-union scheme, Eurozone residents would lose the right to buy the government bonds of other member countries, and member governments would no longer be allowed to sell their bonds to foreigners. But this would be a small price to pay for the restoration of fiscal sovereignty.

This new regime would also make the financing of fiscal deficits an entirely internal matter for individual countries: if a member government goes bust, only its own citizens will be affected. That would remove the justification for Brussels or any other outsiders to meddle in the fiscal policy of member nations, thereby bolstering the democratic institutions of member governments as they regain the ability to respond to voter demands on recessions and public health crises with their own fiscal policies.

This internalization of fiscal policy will also impose discipline on individual governments because they will no longer be able to blame their troubles on the whims of international investors (such as the unscrupulous investment funds noted earlier) or supranational institutions such as the EU and the IMF. This is as it should be: a government that cannot even persuade its own people to hold its bonds has no reason to expect foreigners to buy those bonds instead. That should be welcome news for Germans and others who have been unhappy with the prospect that they might be forced to rescue countries that opted for profligate fiscal policies.

All efficiency gains from the free movement of capital within the Eurozone will also be retained by the private sector because the proposed capital controls apply only to one asset class that lies outside the private sector: government bonds. And foreign holdings of government bonds have never proved to be the best use of capital.

With minimal capital flight and short-term interest rates controlled by the inflation-fighting ECB, bond yields are also likely to stabilize. Because capital flight will be minimal, bond yields in countries that experienced capital outflows in the old framework are likely to decline, while those in countries that experienced capital inflows will go up.

Transitioning to and enforcing the new framework will involve additional costs. A separate arrangement will also have to be made to allow the ECB to hold member governments' bonds for the conduct of monetary policy. But these are not insurmountable issues. Even if some investors manage to find ways around the new rule, the destabilizing capital flight that has plagued the Eurozone for so long will be minimized as long as most institutional investors abide by it.

Fiscal Dis-Union Will also Normalize Monetary Policy

This proposal would also provide massive relief to the ECB, which has been forced to carry out numerous unconventional monetary policies such as QE and negative interest rates precisely because the defective SGP and the above mentioned capital flight prevented member governments from employing fiscal policy to provide necessary support for their economies.

Even though the ECB did everything it could, there is no reason for monetary easing to work when borrowers have disappeared because of balance sheet problems and the economy is in Cases 3 and 4. This loss of monetary policy effectiveness has been amply demonstrated by the ECB's failure to meet its inflation target for 12 consecutive years starting in 2008 despite massive amounts of QE (Figure 2.13) and negative interest rates.

When a recession is caused by a lack of private-sector borrowers, the government must act as borrower of last resort to keep the economy going, and the proposal above would allow Eurozone member governments to perform that role for the first time. That would free the ECB from a burden it could never bear and allow it to exit from the ineffective and potentially costly unconventional monetary easing measures it has been forced to implement. That should be welcome news for the Germans and others who were unhappy with the central bank's “excessively” accommodative policies. In other words, the proposed framework will help normalize not only the fiscal policies of Eurozone member countries, but also the monetary policy of the ECB.

Differentiated Risk Weights as an Alternative to Fiscal Dis-Union

Another less drastic way to keep savings from leaving the country would be to assign lower risk weights to institutional investors' holdings of domestic government bonds relative to foreign government debt. In other words, institutions would be required to hold more capital against holdings of foreign government bonds than against holdings of domestic government bonds, even if they are denominated in the same currency. This could be justified on the grounds that investors should know the risk characteristics of their domestic bond market best.

In this way, Spain's excess savings would be encouraged to flow into Spanish government bonds and Portugal's savings into Portuguese government bonds. The resulting inflow of domestic savings into domestic government bond markets would lower bond yields and provide these countries with the fiscal space they need to engage in necessary fiscal stimulus. Indeed the fiscal dis-union proposal mentioned above should be reinforced with differentiated risk weights so that it will work even better.

The point is that any country that is suffering from a recession caused by excess private-sector savings should be able to finance the necessary fiscal stimulus if it can channel the excess savings that triggered the recession into its own government bond market. The low government bond yields that result should also make many public works projects self-financing if they are carefully chosen. If fiscal dis-union or differentiated risk weights enabled Eurozone governments to utilize this self-corrective mechanism of economies in Cases 3 and 4, then member governments would be no worse off than non-Eurozone governments in their ability to support an economy suffering from a shortage of borrowers.

Recycling Peripheral Savings Back to Peripheral Countries

There is also an option, at least in theory, of recycling departed savings back to the country of origin. For such recycling to work smoothly, however, countries like Germany that are experiencing capital inflows must borrow those funds and then re-lend them to countries like Spain in some sort of automatic arrangement. It has to be automatic so that bond market participants would not have to worry about bond yields being pushed higher by uncertainties surrounding the recycling.

That means net-inflow countries such as Germany would have to quickly determine how much to borrow and recycle back to Spain, Portugal, and so on. But the politics of such a mechanism—including the question of how much to borrow and who will assume the risk—are likely to be difficult to resolve.

The €750 billion package agreed to in July 2020 can be considered a kind of recycling program. The fact that it took the shock of over 100,000 COVID-19 deaths in Europe and more than four full days of arduous negotiations suggests that this approach to recycling is not easy.

If recycling is politically too cumbersome and difficult, perhaps it should be reserved only for truly region-wide challenges like the recent pandemic and Russian induced energy crisis. For day-to-day fiscal operations, fiscal dis-union reinforced with differentiated risk weights should be used to keep recession-inducing excess savings from leaving the country.

Misplaced Fear of “Diabolical” Feedback Loop

Unfortunately, because of the negative feedback loop observed between sovereign and banking crises during the Eurozone debacle that started in 2010, many Eurozone officials are not at all enthusiastic about allowing domestic financial institutions to hold more of their own government's bonds. Indeed, their current inclination is to make it more difficult for domestic banks to do so. But that will make it even harder for member countries to use their own excess private-sector savings to fight balance sheet recessions.

Moreover, this fear of the negative feedback loop is totally misplaced because the origin of the loop is the fundamental inability of Eurozone governments to use fiscal policy to tackle balance sheet recessions. This inability guarantees that Eurozone economies in balance sheet recessions will implode when a debt-financed bubble bursts, which, in turn, will exacerbate banking sector problems. The banking problems arise not only because banks have lent money to bubble participants, but also because the imploding economy makes it difficult for all borrowers to service their debts. And the same inability to use fiscal policy also prevents the governments from helping their banks, making the situation doubly worse.

When investors realize that the government is unable to stop either the implosion of the economy or the explosion of nonperforming loans (NPLs) in the banking system, they become rightfully scared and move their money to safer locations abroad, resulting in capital flight and higher government bond yields at home. The higher bond yields then force even more austerity on the government, which further exacerbates problems in the economy and the banking sector in a vicious cycle.

The correct way to address this “diabolical” feedback loop is to allow governments to combat balance sheet recessions with fiscal stimulus from the outset, thereby averting the vicious cycle. Once the economy stabilizes, the authorities can repair the banking system with the time-honored measures that are explained in Chapter 8. With no implosion of the domestic economy or the banking system, excess savings in the country will head toward the nation's own government bonds instead of toward higher-priced, lower-yielding foreign government bonds.

Making Monetary Union Work without Fiscal Union

Making monetary union work without fiscal union was never meant to be straightforward. And the “price” of regaining full fiscal sovereignty in a monetary union is fiscal dis-union. Whether that price tag is too high for member countries to regain fiscal freedom should be decided by the voters.

Amending the SGP in the manner recommended here would not be easy either. The Financial Times' Martin Wolf, commenting on the author's dis-union proposal, wrote that while the proposal itself was interesting, legal and bureaucratic hurdles would make implementation and enforcement problematic.6 But the EU has already made numerous supposedly impossible procedural changes in response to EMU challenges, including the inauguration of the banking union and the introduction of capital controls during the crisis in Cyprus. The recent €750 billion EU fiscal package was also supposed to be “impossible.”

The dis-union proposal should also be good news for Germans and others concerned about the endgame for the ECB's “crazy” monetary easing policies. The proposed measures would also free Germany from both the pressure to implement more fiscal stimulus and the fear of rescuing profligate member countries. In other words, Germany and other frugal countries in northern Europe should support the present proposal because it gives them everything they have been demanding.

Unlike those who argue that the euro project was a disastrous experiment that should never have been tried, the author believes the euro is one of humanity's greatest achievements, with bright and dedicated people from across the region striving for years to make it work. And it worked quite well before 2008, when most economies were in Cases 1 and 2.

The Eurozone ran into massive problems when it fell into Cases 3 and 4, when fiscal policy became absolutely essential, as predicted by the author in his 2003 book. That means the fundamental cause of the crisis is the Eurozone's inability to deal with economies in Cases 3 and 4, not the absence of fiscal union, lack of progress in structural reforms, or insufficient fiscal stimulus in Germany.

All that is needed in the Eurozone is to ensure that member countries suffering from recessions caused by excess private-sector savings—even at zero interest rates—are able to channel those savings into their own government bond markets, thereby enabling member governments to use those savings to fight recessions. If government expenditures are directed to carefully selected, self-financing projects made possible by low bond yields, there will be no increase in future taxpayers' burden, either.

It is hoped that the EU, the ECB, and member governments will open their eyes to the deflationary danger posed by their private sectors' large financial surpluses and implement the fiscal measures proposed here before it is too late. If they do, European voters will no longer be left feeling helpless and can then be expected to resume voting in a direction more conducive to the proper functioning of democracy. The United Kingdom may also rethink its ties with the Eurozone when the latter starts to demonstrate robust growth.

The German Model Is Not for Everyone

At the opposite extreme, the Germans have been obsessed with the notion that the government budget must be balanced. But this obsession ignores the iron law of macroeconomics—namely, that if someone is saving money, someone else must borrow and spend those savings to keep the national economy from contracting. The German preference for balanced budgets—known as schwarz nul, or black zero—makes sense only if the German private sector is not a net saver or if foreigners are willing to borrow and spend Germany's savings by running trade deficits with the country. The fact that the German private sector has been a huge net saver (i.e., has been running a financial surplus) to the tune of 6.72 percent of GDP on average for the last two decades means it is foreigners who have propped up the economy. In other words, Germany kept its economy going by running huge trade surpluses with the rest of the world.

Under ordinary circumstances, such large and continuous trade surpluses would have pushed the country's exchange rate sky-high and reduced its export competitiveness and income growth. But Germany's membership in the Eurozone has virtually eliminated this currency appreciation risk and allowed the country to continue exporting. That allowed the country to export its way out of post-2000 balance sheet recession, something that Japanese could not do ten years earlier because the yen kept on appreciating with Japan's large trade surpluses. Although President Donald Trump once complained loudly about the German exchange rate and U.S. trade deficits with the country, he could do nothing about it because Germany belonged to the euro.

Even if there is nothing on the horizon that might dislodge Germany from the plush position it has found for itself in the Eurozone, it makes no sense for the country to insist that other member countries follow its lead. The German model is not a model for other countries or for the world. First, if all other Eurozone members became like Germany, the region would be running such a large trade surplus that the exchange rate of euro would rocket higher, destroying the export competitiveness of Germany and everyone else. Second, by definition, all countries cannot run trade surpluses at the same time. The German model is a partial equilibrium model that works only for Germany in the Eurozone, not a general equilibrium model that works for everyone.

Nothing on the horizon is likely to dislodge Germany from the unique position it currently enjoys, but the country should be mindful of the fact that it has that position precisely because other countries are not behaving like it does. It should also work harder to help others in the Eurozone because the disintegration of the bloc has the potential to hurt Germany more than other members.

Three Problems with Milton Friedman's Call for Free Markets

When Milton Friedman, Nobel Laureate and neoliberal champion of free markets, monetary policy, and small government, visited Japan in the 1950s and spoke to economist Kazushi Nagasu, he had strong things to say about the plight of his people: “I am a Jew … I do not think I need to tell you what kind of horrible deaths Jewish people had to face. The real drive behind my argument for free markets is the bloodied cries of Jewish people who perished under Hitler's and Stalin's regimes, and their message is that the best way to happiness is to have a framework that brings people together where states, races and political systems have no influence.”7

Although many sympathize with Friedman and agree that a free market provides that ideal framework, he is wrong on at least three counts. The first is his assumption that markets driven by a profit-maximizing private sector can never go wrong. But every several decades the private sector loses its head in a bubble—something observed most recently in the dot-com bubble that burst in 2000 and the housing bubble that imploded in 2008.

During a bubble, the private sector engages in a frenzy of speculation and ends up misallocating trillions of dollars of resources, the scale of which no government could ever hope to match. In other words, markets work well when businesses and households have cool heads, but not when a bubble has formed. And bubbles are easier to form in the pursued era than in the golden era when Friedman was formulating his theories.

When the bubble bursts, the private sector comes to its senses and realizes it must remove its debt overhang by minimizing debt. But when a large part of the private sector is engaged in debt minimization at the same time, the economy falls into a devastating fallacy-of-composition problem called a balance sheet recession.

This is where Friedman made his second mistake. He argued that monetary policy—whereby the central bank supplies liquidity and lowers interest rates—should be mobilized to counter recessions. That was the right policy to employ when he was developing his theories in the 1950s and 1960s, as the United States was in a golden era and its economy was in Case 1 or 2. But once the economy enters a balance sheet recession or the pursued phase and the private sector stops borrowing money, the economy is in Case 3 or 4, and monetary policy is no longer effective. It stops working because an absence of borrowers even at zero interest rates prevents funds supplied by the central bank from entering the real economy.

His third mistake was that his emphasis on small government caused him to oppose the use of fiscal stimulus, which to him symbolized big government and intervention by the state. But in a balance sheet recession, the government must act as borrower (and spender) of last resort. There is no other way to keep the economy out of a deflationary spiral and give the private sector the income it needs to pay down debt and rebuild its balance sheet.

Friedman's overriding emphasis on the supremacy of markets, monetary policy, and small government allows no room for government to act as borrower of last resort. But it was the failure of the Brüning government to do just that that led to Germany's economic collapse and paved the way for Adolf Hitler's rise to power in 1933. The failure of the French, U.K. and U.S. governments to act as borrowers of last resort not only enhanced Hitler's reputation, but also prevented those governments from presenting a credible deterrent to his rapidly expanding military. To prevent the tragedy of another Holocaust, it is essential that the public be taught what a balance sheet recession is and how to fight it with fiscal stimulus.

Notes

- 1 The Neuer Markt changed its name to TecDAX on March 24, 2003.

- 2 Readers interested in seeing how the competitiveness issue evolved in the post-2008 Eurozone are referred to Chapter 5 of the author's previous book, The Escape from Balance Sheet Recession and the QE Trap (2015), for a more detailed discussion.

- 3 This is the original treaty that led to the creation of the euro and SGP.

- 4 Koo, Richard C. (2003), Balance Sheet Recession: Japan's Struggle with Uncharted Economics and its Global Implications, Singapore: John Wiley & Sons (Asia), p. 234.

- 5 Koo, Richard C. (2008), The Holy Grail of Macroeconomics: Lessons from Japan's Great Recession, Singapore: John Wiley & Sons (Asia), p. 250.

- 6 Wolf, Martin (2015), “A Handy Tool—But Not the Only One in the Box,” Financial Times, January 4, 2015. https://www.ft.com/content/0d3f41dc-86bf-11e4-8a51-00144feabdc0.

- 7 Uchihashi, Katsuto (2009), “Shinpan Akumu-no Saikuru: Neo-riberarizumu Junkan” (“Cycle of Nightmares: The Recurrence of Neoliberalism”), updated version, in Japanese, Bunshun Bunko, Japan, pp. 88–89.